Abstract

Most space launches result in uncontrolled rocket body reentries, creating casualty risks for people on the ground, at sea and in aeroplanes. These risks have long been treated as negligible, but the number of rocket bodies abandoned in orbit is growing, while rocket bodies from past launches continue to reenter the atmosphere due to gas drag. Using publicly available reports of rocket launches and data on abandoned rocket bodies in orbit, we calculate approximate casualty expectations due to rocket body reentries as a function of latitude. The distribution of rocket body launches and reentries leads to the casualty expectation (that is, risk to human life) being disproportionately borne by populations in the Global South, with major launching states exporting risk to the rest of the world. We argue that recent improvements in technology and mission design make most of these uncontrolled reentries unnecessary, but that launching states and companies are reluctant to take on the increased costs involved. Those national governments whose populations are being put at risk should demand that major spacefaring states act, together, to mandate controlled rocket reentries, create meaningful consequences for non-compliance and thus eliminate the risks for everyone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In May 2020, an 18 t core stage of a Long March 5B rocket reentered the atmosphere from orbit in an uncontrolled manner after being used to launch an unmanned experimental crew capsule. Debris from the rocket body, including a 12-m-long pipe, struck two villages in the Ivory Coast, causing damage to several buildings. One year later, another 18 t core stage of a Long March 5B rocket made an uncontrolled reentry after being used to launch part of China’s new Tiangong space station into low Earth orbit. This time, the debris crashed into the Indian Ocean. These two rocket stages were the heaviest objects to reenter in an uncontrolled manner since the Soviet Union’s Salyut-7 space station in 1991.

China received criticism for imposing the reentry risks of its rockets onto the world, including from US government officials. However, there is no international consensus on the acceptable level of risk, and other spacefaring states—including the USA—make similar choices concerning uncontrolled reentries. In 2016, the second stage of a SpaceX rocket was abandoned in orbit; it reentered one month later over Indonesia, with two refrigerator-sized fuel tanks reaching the ground intact.

The added technological complexity and cost involved in achieving controlled reentries helps to explain the shortage of international rules on this matter. Moreover, casualty risks are usually assessed on a launch-by-launch basis, which keeps them low and makes it easier for governments to justify uncontrolled reentries. However, as humanity’s use of space expands, cumulative risks should also be considered. Launch providers have access to technologies and mission designs today that could eliminate the need for most uncontrolled reentries. The challenge, in an increasingly diverse and competitive space launch market, is not only to raise safety standards but to ensure that everyone is subject to them, and to do all this without creating unreasonable barriers for new entrants.

The problem

Launch sequences vary between rocket models. Some rockets have ‘boosters’, which are dropped suborbitally during the launch sequence with some precision and usually into the ocean. All rockets have a ‘core’ or ‘first stage’, some of which are designed to be suborbital and others orbital. If the core stage attains orbit, it is then either abandoned in orbit (as with the Long March 5B rockets) or brought back through a controlled reentry. When a rocket stage is abandoned with sufficiently low perigees, gas drag gradually reduces its altitude and eventually causes it to reenter the atmosphere in an uncontrolled way, which can occur at any point under its flight path. In contrast, controlled reentries from orbit use an engine burn to direct the stage to a remote area of ocean or recovery zone. Most rockets also have one or more ‘upper stages’, which deploy the ‘payload’ (such as one or more satellites). Although upper stages are sometimes brought back to Earth through a controlled reentry, they are often abandoned in orbit. This article focuses on abandoned orbital stages (generically called ‘rocket bodies’ hereafter) that return to Earth in an uncontrolled way—creating danger for people on the surface.

In 2020, over 60% of launches to low Earth orbit resulted in a rocket body being abandoned in orbit1. Remaining in orbit for days, months or even years, these large objects pose a collision hazard for operational satellites. They can also, in the event of a collision or an explosion of residual fuel, fragment into thousands of smaller but still potentially destructive pieces of space debris2, creating even more hazards for satellites. There is yet another risk, which is the focus of this paper: when intact stages return to Earth, a substantial fraction of their mass survives the heat of atmospheric reentry as debris3. Many of the surviving pieces are potentially lethal, posing serious risks on land, at sea and to people in aeroplanes.

In the USA, the Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices (ODMSPs) apply to all launches and require that the risk of a casualty from a reentering rocket body is below a 1-in-10,000 threshold4. However, the US Air Force waived the ODMSP requirements for 37 of the 66 launches conducted for it between 2011 and 2018, on the basis that it would be too expensive to replace non-compliant rockets with compliant ones5. NASA waived the requirements seven times between 2008 and 2018, including for an Atlas V launch in 2015 where the casualty risk was estimated at 1 in 600 (ref. 6).

The 1-in-10,000 threshold for casualty risk is arbitrary7 and makes little sense in an era when new technologies and mission profiles enable controlled reentries. It also fails to address low-risk, high-consequence outcomes, such as a piece of a rocket stage crashing into a high-density city or a large passenger aircraft. In the latter case, even a small piece could cause hundreds of casualties3.

Internationally, there is no clear and widely agreed casualty risk threshold. The 2010 UN Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines recommend that reentering spacecraft not pose ‘an undue risk to people or property’, but do not define what this means8. The 2018 UN Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities call on national governments to address risks associated with the uncontrolled reentry of space objects, but do not specify how9. There is no binding treaty that addresses rocket body reentries, apart from the 1972 Liability Convention, which stipulates that ‘[a] launching State shall be absolutely liable to pay compensation for damage caused by its space object on the surface of the earth or to aircraft in flight’10.

Although the possibility of liability often induces good behaviour, on this issue governments have apparently chosen to bear the slight risk of having to compensate for one or more casualties, rather than to require launch providers to make expensive technological or mission design changes. As in some other areas of government and commercial activity, ‘liability risk’ is treated as just another cost of doing business11. This approach may have been made easier by the fact that the casualty risk is disproportionately borne by the populations of some of the poorest states in the world, as Fig. 1 demonstrates.

a, Number of rocket bodies with perigee of <600 km and associated global casualty expectation for spacefaring states with large contributions (Europe treated as a single unit). b, Pie chart of the proportion of the total global casualty expectation contributed by each state. c, Standard casualty expectation as a function of orbital inclination for reentry of a single object and the 2020 global population. d, Casualty expectation of rocket bodies currently in orbit by latitude and 2020 population density. Casualty expectation is the number of casualties per square metre of casualty area as described in ref. 13. Casualty area, which is the total area over which debris could cause a casualty for a given reentry, is not modelled. In all panels, only rocket bodies with perigees at or below 600 km are included, on the basis of the satellite catalogue as of 5 May 202212. This approximates the population of long-lived abandoned rocket bodies that might reasonably be expected to deorbit.

Assessing the casualty risk

The publicly available satellite catalogue12 provides data for objects that are currently in orbit, as well as those that have reentered, including rocket bodies. Over the past 30 years (4 May 1992–5 May 2022), more than 1,500 rocket bodies have deorbited12. Of these, we estimate that over 70% deorbited in an uncontrolled manner, corresponding to a casualty expectation of about 0.015 m−2. This means that, at face value, if the average rocket body were to cause a casualty area of 10 m2, there was an approximately 14% chance of one or more casualties over this time. Although no such event occurred, or at least was reported, these calculations show that the incurred risk has been far from negligible.

The casualty expectation is calculated as follows. Since each abandoned rocket body is left at a specific orbital inclination, the probability that an uncontrolled rocket body (or any object) reenters at a given latitude can be expressed through a latitude weighting function. The weight associated with a latitude represents the fraction of time that an object on a fixed inclination spends over the latitude in question. An object on a zero-degree inclination orbit would have a weighting function that is unity at the equator and zero everywhere else, while an object on a polar orbit would have a weighting function that is a constant for all latitudes. For all other inclinations, an individual orbit will have a weighting function with peaks at the latitudes close to the value of the orbital inclination, a U-shaped distribution between the peaks, and weights of zero at latitudes higher than the inclination. The weighting function for an individual object is normalized such that the summation of weights over all latitudes is unity, while the weighting function for a population is the sum of the individual functions.

A casualty expectation is determined by taking the product of the weighting function and the population density at a given latitude and summing the result over all latitudes. For reference, Fig. 1c shows the casualty expectation for a single reentering object as a function of its orbital inclination, consistent with previous work13. Space objects with an inclination around 30° spend more time over higher population densities and so have a higher casualty expectation. The datasets for the world population for different years are GPWv4 (ref. 14).

A rocket body reentry is taken to be uncontrolled in this analysis if the time span between the rocket’s launch date and reentry date is 7 d or longer. Several time spans were tested, and 3–7 d delays yield comparable results, with the longer delay being more conservative and thus favoured in this analysis. For the casualty expectation of the past 30 yr, reported above, the 2005 world population is used.

This basic procedure can also be used to estimate the future risk of uncontrolled rocket body reentries.

Results

The future rocket body reentry risk can be modelled in several ways; we explore two. First, the long-term risk resulting from the build-up of rocket bodies in orbit can be estimated by looking at which rocket body orbits have a perigee lower than 600 km, with this perigee representing an imperfect but plausible division between rocket bodies that will deorbit in the coming decades and those that require much longer timescales. For this cut, there are 651 rocket bodies, with a corresponding casualty expectation of 0.01 m−2. Second, we take the trend of rocket body reentries from the past 30 yr and apply it to the next 10 yr, giving rise to a casualty risk of 0.006 m−2 for that period. Both of these are conservative estimates, as the number of rocket launches is increasing quickly. Assuming again that each reentry spreads lethal debris over a 10m2 area, we conclude that current practices have on order a 10% chance of one or more casualties over a decade.

In the first method (perigee cut), there is no explicit reentry timescale. As such, only the year 2020 world population is used to calculate the corresponding casualty expectation. This method most clearly identifies the consequences of the long-lived on-orbit rocket body population. However, it does not account for the short-lived rocket body population, such as those bodies that reenter within a few weeks after launch. Nor does the method consider world population growth.

In the second method, these shortcomings are addressed, in part, by using the reentry history as a proxy for the future rocket body reentry rate. In this approach, the catalogue is searched for all rocket bodies that have reentered in the past 30 yr. Because it is not immediately clear from the catalogue alone which of these reentered uncontrollably, we assume that any rocket body spending more than 7 d in orbit is uncontrolled, as noted above. Finally, the weighting functions for each uncontrolled reentry are averaged over 30 yr to arrive at a total average weighting function representative of one year of reentries.

World population growth is modelled as a 1% population increase per year. Assuming no changes to the reentry rate or the rocket body population distribution, the resulting total average weighting function is multiplied by the world population density distribution for each year, with the results summed over 10 yr. An additional sum over latitude is done to obtain the 10 yr casualty risk.

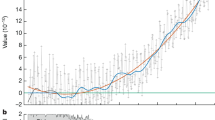

The two methods yield similar results, despite the different approaches. Moreover, the respective weighting functions have a common feature: the largest weights are concentrated near the equator, as shown in Fig. 2.

Each curve is the sum of the rocket bodies’ normalized time spent over each latitude. Two models are shown: the sum of all rocket bodies currently in orbit with perigee under 600 km, and a 10 yr projection. The latter uses the historical reentries of uncontrolled rocket bodies, from 4 May 1992 to 5 May 2022, to determine an average yearly total weighting function. In this figure, that average is multiplied by ten to show a weighting function for a 10 yr period.

Many of the rocket bodies that lead to uncontrolled reentries are inferred to be associated with launches to geosynchronous orbits, located near the equator. As a result, the cumulative risk from rocket body reentries is significantly higher in the states of the Global South, as compared with the major spacefaring states. The latitudes of Jakarta, Dhaka, Mexico City, Bogotá and Lagos are at least three times as likely as those of Washington, DC, New York, Beijing and Moscow to have a rocket body reenter over them, under one estimate, on the basis of the current rocket body population in orbit (see Fig. 3).

Some major and high-risk cities are labelled: 1, Moscow; 2, Washington, DC; 3, Beijing; 4, Dhaka; 5, Mexico City; 6, Lagos; 7, Bogotá; 8, Jakarta. The chosen weighting function is for all rocket bodies currently in orbit with perigees less than 600 km in altitude. The outline of the continents is an equirectangular projection, taken from the Python package Cartopy.

This situation, of risks from activities in the developed world being borne disproportionately by populations in the developing world, is hardly unprecedented. Powerful states often externalize costs and impose them on others, with greenhouse gas emissions being just one example15. The disproportionate risk from rocket bodies is further exacerbated by poverty, with buildings in the Global South typically providing a lower degree of protection; according to NASA, approximately 80% of the world’s population lives ‘unprotected or in lightly sheltered structures providing limited protection against falling debris’7.

Discussion

Fortunately, allowing rocket bodies to reenter in an uncontrolled manner is increasingly becoming a choice rather than a technological limitation. Controlled reentries from orbit require engines that can reignite, enabling the launch provider to direct the rocket body away from populated areas, usually into a remote area of ocean16. Some older rocket models that lack reignitable engines are still used by some launch providers; these will need to be upgraded or replaced to achieve a safe, controlled reentry regime.

Performing a controlled reentry also requires having extra fuel on board, above and beyond that required for launching the payload. Some launch providers operating modern rockets with reignitable engines deplete the fuel on board to boost the payload as high as possible, thus saving customers time and fuel—since otherwise the payload will have to use its own thrusters to raise its orbit. However, in doing so, the providers are denying themselves the opportunity for a controlled reentry. Such an approach to mission design will also have to be changed to achieve a safe, controlled reentry regime.

Most of these measures cost money. In the case of the Delta IV rocket, the US government reportedly granted waivers because of the high costs of upgrades5, even though, as the entity procuring these launches, it was well positioned to absorb the increased cost of safer missions. In the case of commercial missions, the costs associated with a move to controlled reentries could affect the ability of a launch provider to compete. Yet increased costs often arise when safety, environmental and other negative externalities are internalized. This is where rules and regulations come in: when done well, they ensure a level playing field so that no single company, even a new entrant, loses out from improved practices.

Solving the collective action problem

National governments could raise the standards applicable to launches from their territory or by companies incorporated there. However, individual governments might have competing incentives, such as reducing their own costs or growing a globally competitive domestic space industry. Uncontrolled rocket body reentries constitute a collective action problem; solutions exist, but every launching state must adopt them.

We have been here before. In the 1970s, scientists warned that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used in refrigeration systems were converting and thus reducing ozone molecules in the atmosphere, which in turn allowed more cancer-causing ultraviolet radiation to reach the surface. In 1985, the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer was adopted17. This provided a framework for phasing out the use of CFCs, with the specific chemicals and timelines set out in the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer18. These two treaties, which have been ratified by every single UN member state, have solved the collective action problem. They have reduced the global use of CFCs by 98%, prevented further damage to the ozone layer and thus prevented an estimated two million deaths from skin cancer every year.

The 1970s also saw a growing risk to oceans and coastlines from oil spills as well as efforts, nationally and internationally, to adopt a requirement for ‘double hulls’ on tankers. The shipping industry, concerned about increased costs, was able to stymie these efforts—until 1989, when the Exxon Valdez spilled roughly 11 million gallons of oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Media coverage of the accident made the issue of oil spills a matter of public concern, and after the National Transportation Safety Board concluded that a double hull would have substantially reduced if not eliminated the spill19, the US government required all new tankers calling at US ports to have double hulls20. This unilateral move then prompted the International Maritime Organization to amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL Convention) in 1992 to require double hulls on new tankers and, through further amendments in 2001 and 2003, to accelerate the retirement of single-hulled tankers.

The 1992 amendments to the MARPOL Convention have since been ratified by 150 states (including the USA, Liberia and Panama), representing 98% of the world’s shipping tonnage. This precedent, of oil spills and the double-hull requirement, is especially relevant for uncontrolled rocket body reentries because it concerns transportation safety in an area beyond national jurisdiction, with oil spills posing risks for all coastal states.

Those national governments whose populations are being put at disproportionate risk by uncontrolled rocket bodies should demand that major spacefaring states mandate controlled rocket reentries, create meaningful consequences for non-compliance and thus eliminate the risks for everyone. If necessary, they could initiate negotiations on a non-binding resolution or even a treaty—because they have a majority at the United Nations General Assembly. A multilateral treaty might not be ratified by the major spacefaring states, but it would still draw widespread attention to the issue and set new expectations for behaviour. This is what happened with the 1997 Anti-Personnel Landmines Convention: although not ratified by the USA, Russia or China, it led to a marked reduction in the global use of antipersonnel mines, with non-ratifiers also changing their behaviour21.

On the issue of uncontrolled rocket body reentries, the states of the Global South hold the moral high ground: their citizens are bearing most of the risks, and unnecessarily so, since the technologies and mission designs needed to prevent casualties exist already.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available via GitHub at: https://github.com/etwright1/uncontrolledrocketreentries

Code availability

The analysis scripts used in this study are available via GitHub at: https://github.com/etwright1/uncontrolledrocketreentries

References

ESA’s Annual Space Environment Report Publication GEN-DB-LOG-00288-OPS-SD (European Space Agency Space Debris Office, 2021); https://www.sdo.esoc.esa.int/environment_report/Space_Environment_Report_latest.pdf

Anz-Meador, P., Opiela, J., Shoots, D. & Liou, J. C. History of On-Orbit Satellite Fragmentations 15th edn, NASA/TM-2018-220037 (NASA, 2018).

Ailor, W. Large Constellation Disposal Hazards (Aerospace Corporation, 2020).

Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices November 2019 Update (US Government, 2019).

Verspieren, Q. The US Air Force compliance with the Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices. In Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference (Maui Economic Development Board, 2020).

Liou, J. C. Orbital Debris Briefing Report JSC-E-DAA-TN50234 (NASA, 2017); https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20170011662

Process for Limiting Orbital Debris NASA-STD-8719.14B (NASA, 2019).

Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), 2010).

Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities A/AC.105/2018/CRP.20 (United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPOUS), 2018).

Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects RES 2777 XXVI (United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), 1971).

Abraham, K. S. Environmental liability and the limits of insurance. Columbia Law Rev. 88, 942–957 (1988).

Kelso, T. S. CelesTrak https://celestrak.com/ (2022).

Patera, R. Hazard analysis for uncontrolled space vehicle reentry. J. Spacecr. Rockets 45, 1031–1041 (2008).

Gridded Population of the World, Version 4.11 (GPWv4): UN WPP-Adjusted Population Count (Center for International Earth Science Information Network—CIESIN, 2022); https://sedac.ciesin.columbia.edu/data/set/gpw-v4-population-density-rev11

Faber, D. Capitalizing on Environmental Injustice: the Polluter–Industrial Complex in the Age of Globalization (Rowman & Littlefield, 2008).

De Lucia, V. & Iavicoli, V. From outer space to ocean depths: the ‘spacecraft cemetery’ and the protection of the marine environment in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Calif. West. Int. Law J. 2, 367–369 (2019).

Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer (United Nations Environment Programme, 1985).

Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (United Nations Environment Programme, 1987).

Marine Accident Report: Grounding of the US Tankship Exxon Valdez on Bligh Reef, Prince William Sound Near Valdez, Alaska March 24 163 (National Transportation Safety Board, 1989).

USC Title 33: Navigation and Navigable Waters Ch. 40, Section 2701 et seq. (Office of the Law Revision Counsel, 1990).

Bower, A. Norms Without the Great Powers: International Law and Changing Social Standards in World Politics (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. co-led the identification and conceptualization of the problem, conducted the legal and policy analyses and led the writing. E.W. conducted the data analysis and risk calculations, produced the figures and contributed to the writing. A.B. co-led the identification and conceptualization of the problem, directed the data and risk analyses and contributed to the writing. C.B. contributed to the identification and conceptualization of the problem and provided comments and feedback on the work. All authors participated in conducting background research, discussing the results of the analyses and formulating possible policy solutions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Byers, M., Wright, E., Boley, A. et al. Unnecessary risks created by uncontrolled rocket reentries. Nat Astron 6, 1093–1097 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01718-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01718-8