Abstract

Abundances of the highly siderophile elements (HSEs) in silicate portions of Earth and the Moon provide constraints on the impact flux to both bodies, but only since ~100 Myr after the beginning of the Solar System (hereafter tCAI). The earlier impact flux to the inner Solar System remains poorly constrained. The former dwarf planet Vesta offers the possibility to probe this early history, because it underwent rapid core formation ~1 Myr after tCAI and its silicate portions possess elevated chondritic HSE abundances. Here we quantify the material accreted into Vesta’s mantle and crust and find that the HSE abundances can only be explained by the bombardments of planetesimals from the terrestrial planet region. The Vestan mantle accreted HSEs within the first 60 Myr; its crust accreted HSEs throughout the Solar System history, with asteroid impacts dominating only since ~4.1 billion years ago. Our results indicate that all major bodies in the inner Solar System accreted planetesimals predominantly from the terrestrial planet region. The asteroid belt was either never significantly more massive than today, or it rapidly lost most of its mass early in the Solar System history.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are all included in the manuscript (Methods). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

At present, iSALE is not fully open source. It is distributed on a case-by-case basis to academic users in the impact community, strictly for non-commercial use. Scientists interested in using or developing iSALE should see http://www.isale-code.de for a description of application requirements.

References

Hartmann, W. K. Early lunar cratering. Icarus 5, 406–418 (1966).

Rubie, D. C. et al. Highly siderophile elements were stripped from Earth’s mantle by iron sulfide segregation. Science 353, 1141–1144 (2016).

Morbidelli, A. et al. The timeline of the lunar bombardment: revisited. Icarus 305, 262–276 (2018).

Zhu, M.-H. et al. Reconstructing the late-accretion history of the Moon. Nature 571, 226–229 (2019).

Kleine, T. et al. Hf–W chronology of the accretion and early evolution of asteroids and terrestrial planets. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 5150–5188 (2009).

Thiemens, M. M. et al. Early Moon formation inferred from hafnium–tungsten systematics. Nat. Geosci. 12, 696–700 (2019).

Borg, L. E. et al. Chronological evidence that the Moon is either young or did not have a global magma ocean. Nature 477, 70–72 (2011).

Connelly, J. N. et al. The absolute chronology and thermal processing of solids in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 338, 651–655 (2012).

Binzel, R. P. & Xu, S. Chips off of Asteroid 4 Vesta: evidence for the parent body of basaltic achnodrite. Science 250, 186–191 (2003).

Touboul, M. et al. Hf–W chronology of the eucrite parent body. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 156, 106–121 (2015).

Hublet, G. et al. Differentiation and magmatic activity in Vesta evidenced by 26Al–26Mg dating in eucrites and diogenites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 218, 73–97 (2017).

Day, J. M. D. et al. Late accretion as a natural consequence of planetary growth. Nat. Geosci. 5, 614–617 (2012).

Dale, C. W. et al. Late accretion on the earliest planetesimals revealed by the highly siderophile elements. Science 336, 72–75 (2012).

Zuber, M. T. et al. Origin, internal structure and evolution of 4 Vesta. Space Sci. Rev. 163, 77–93 (2011).

Horan, M. F. et al. Highly siderophile elements in chondrites. Chem. Geol. 196, 27–42 (2003).

Fischer-Godde, M. et al. Rhodium, gold and other highly siderophile element abundances in chondritic meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 356–379 (2010).

Day, J. M. D., Brandon, A. D. & Walker, R. J. Highly siderophile elements in Earth, Mars, the Moon, and Asteroids. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 81, 161–238 (2016).

Genda, H. et al. Ejection of iron-bearing giant-impact fragments and the dynamical and geochemical influence of the fragment re-accretion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 470, 87–95 (2017).

Lambrechts, M. & Johansen, A. Rapid growth of gas-giant cores by pebble accretion. Astron. Astrophys. 544, A32 (2012).

Lambrechts, M. & Johansen, A. Forming the cores of giant planets from the radial pebble flux in protoplanetary discs. Astron. Astrophys. 572, A107 (2014).

Levision, H. F., Kretke, K. A. & Duncan, M. J. Growing the gas-giant planets by the gradual accumulation of pebbles. Nature 524, 322–324 (2015).

Schiller, M., Bizzarro, M. & Fernandes, V. A. Isotopic evolution of the protoplanetary disk and the building blocks of Earth and Moon. Nature 555, 507–150 (2018).

Popovas, A., Nordlund, A. & Ramsey, J. P. Pebble dynamics and accretion on to rocky planets—II. Radiative model. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 482, L107–L111 (2019).

Lambrechts, M. et al. Formation of planetary systems by pebble accretion and migration. How the radial pebble flux determines a terrestrialplanete or super-Earth growth model. Astron. Astrophys. 627, A83 (2019).

O’Brien, D. P. et al. Constraining the cratering chronology of Vesta. Planet. Space Sci. 103, 131–142 (2014).

Gomes, R. et al. Origin of the cataclysmic late heavy bombardment period of the terrestrial planets. Nature 435, 466–469 (2005).

Schmedemann, N. et al. The cratering record, chronology and surface age of (4) Vesta in comparison to smaller asteroids and the ages of HED meteorites. Planet. Space Sci. 103, 104–130 (2014).

Bottke, W. F. et al. in Asteroids IV (eds Michel, P. et al.) 701–724 (Univ. Arizona Press, 2015).

Elbeshausen, D. et al. The transition from circular to elliptical impact crater. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 2295–2309 (2013).

Bottke, W. F. et al. The fossilized size distribution of the main asteroid belt. Icarus 175, 111–140 (2005).

Nesvorny, D. et al. Evidence for very early migration of the solar system planets from the Patroclus–Menoetius binary Jupiter Trojan. Nat. Astron. 2, 878–882 (2018).

Morbidelli, A. et al. A sawtooth-like timeline for the first billion years of lunar bombardment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 355, 144–151 (2012).

Hansen, B. M. S. Formation of the terrestrial planets from a narrow annulus. Astrophys. J. 703, 1131–1140 (2009).

Walsh, K. J. et al. A low mass for Mars from Jupiter’s early gas-driven migration. Nature 475, 206–209 (2011).

Izidoro, A. et al. Terrestrial planet formation constrained by Mars and the structure of the asteroid belt. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 453, 3619–3634 (2015).

Neukum, G., Ivanov, B. A. & Hartmann, W. K. Cratering records in the inner Solar System in relation to the lunar reference system. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 55–86 (2001).

Artemieva, N. & Ivanov, B. Launch of martian meteorites in oblique impacts. Icarus 171, 84–101 (2004).

Holsapple, K. A. & Housen, K. R. A crater and its ejecta: an interpretation of Deep Impact. Icarus 191, 586–597 (2007).

Mandler, B. E. & Elkins-Tanton, L. T. The origin of eucrites, diogenites, and olivine diogenits: magma ocean crystallization and shallow magma chamber processes on Vesta. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 48, 2,333–2,349 (2013).

Neumann, W., Breuer, D. & Spohn, T. Differentiation of Vesta: implications for a shallow magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 395, 267–280 (2014).

McSween, H. Y. et al. Composition of the Rheasilvia Basin, a window into Vesta’s interior. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 335–346 (2013).

Neumann, W. Towards 3D modelling of convection in planetesimals and meteorite parent bodies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 490, L47–L51 (2019).

Minton, D. A. & Malhotra, R. Dynamical erosion of the asteroid belt and implications for large impacts in the inner Solar System. Icarus 207, 744–757 (2010).

Russell, C. T. et al. Dawn at Vesta: testing the protoplanetary paradigm. Science 336, 684–686 (2012).

Marchi, S. et al. The violent collisional history of asteroid 4 Vesta. Science 336, 690–694 (2012).

Spoto, F., Milani, A. & Kenzevic, Z. Asteroid family ages. Icarus 257, 275–289 (2015).

Jutzi, M. et al. The structure of the asteroid 4 Vesta as revealed by models of planet-scale collisions. Nature 494, 207–210 (2013).

Consolmagno, G. J. et al. Is Vesta an intact and pristine protoplanet? Icarus 254, 190–201 (2015).

Bottke, W. F. et al. Iron meteorites as remnants of planetesimals formed in the terrestrial planet region. Nature 439, 821–824 (2006).

Raymond, S. N. & Izidoro, A. The empty primordial asteroid belt. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701138 (2017).

Walker, R. J. Highly siderophile elements in the Earth, Moon and Mars: update and implications for planetary accretion and differentiation. Chem. Erde Geochem. 69, 101–125 (2009).

Marchi, S., Canup, R. M. & Walker, R. J. Heterogeneous delivery of silicate and metal to the Earth by large planetesimals. Nat. Geosci. 11, 77–81 (2018).

Tait, K. T. & Day, J. M. D. Chondritic late accretion to Mars and the nature of shergottite reservoirs. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 494, 99–108 (2018).

Marchi, S., Walker, R. J. & Canup, R. M. A compositionally heterogeneous martian mantle due to late accretion. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2338 (2020).

Day, J. M. D., Pearson, D. G. & Taylor, L. A. Highly siderophile element constraints on accretion and differentiation of the Earth–Moon system. Science 315, 217–219 (2007).

Hayashi, C. Structure of the solar nebula, growth and decay of magnetic fields and effects of magnetic and turbulent viscosities on the nebula. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 70, 35–53 (1981).

Izidoro, A. et al. Terrestrial planet formation in a protoplanetary disk with a local mass depletion: a successful scenario for the formation of Mars. Astrophys. J. 782, 31 (2014).

Andrews, S. M. et al. The disk substructures at high angular resolution project (DSHARP). I. Motivation, sample, calibration, and overview. Astrophys. J. Lett. 869, L41 (2018).

Drazkowska, J., Windmark, F. & Dullemond, C. P. Modeling dust growth in protoplanetary disks: the breakthrough case. Astron. Astrophys. 567, A38 (2014).

Clement, M. S. et al. Mars’ growth stunted by an early giant planet instability. Icarus 311, 340–356 (2018).

Warren, P. H. et al. Siderophile and other geochemical constraints on mixing relationships among HED-meteoritic breccias. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 5918–5943 (2009).

Birck, J. L. & Allegre, C. J. Constrasting Re/Os magmatic fractionation in planetary basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 124, 139–148 (1994).

McSween, H. Y. et al. Dawn; the Vesta-HED connection; and the geologic context for eucrites, diogenites, and howardites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 48, 2,090–2,104 (2013).

Steenstra, E. S. et al. An experimental assessment of the potential of sulfide saturation of the source region of eucritex and angrites: implications for asteroidal models of core formation, late accretion and volatile element depletions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 269, 39–62 (2019).

Fu, R. R. et al. Efficient early global relaxation of asteroid Vesta. Icarus 240, 133–145 (2014).

Warren, P. H. Ejecta-megaregolith accumulation on planetesimals and large asteroids. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 46, 53–78 (2011).

Day, J. M. D. & Walker, R. J. Highly siderophile element depletion in the Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 423, 114–124 (2015).

Day, J. M. D. et al. Osmium isotope and highly siderophile element systematics of the lunar crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 289, 595–605 (2010).

Russell, C. T., McSween, H. Y., Jaumann, R. & Raymond, C. A. in Asteroids IV (eds Michel, P. et al.) 419–432 (Univ. Arizona Press, 2015).

Kobayashi, H. et al. Planetary growth with collisional fragmentation and gas drag. Icarus 209, 836–847 (2010).

Lee, D.-C. & Halliday, A. N. Core formation on Mars and differentiated asteroids. Nature 388, 854–857 (1997).

Righter, K. & Drake, M. J. Core formation in Earth’s Moon, Mars, and Vesta. Icarus 124, 513–529 (1996).

Ghosh, A. & McSween, H. Y. A thermal model for the differentiation of asteroid 4 Vesta, based on radiogenic heating. Icarus 134, 187–206 (1998).

Drake, M. J. The eucrite/Vesta story. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 501–513 (2001).

Gupta, G. & Sahijpal, S. Differentiation of Vesta and the parent bodies of other achondrites. J. Geophys. Res. 115, E8 (2010).

Hahn, T. M. et al. Mg-rich harzburgites from Vesta: mantle residua or cumulates from planetary differentiation? Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 514–546 (2018).

Schiller, M. et al. Tracking the formation of magma oceans in the Solar System using stable magnesium isotopes. Geochem. Persp. Lett. 3, 22–31 (2017).

Barrat, J. A. & Yamaguchi, A. Comment on ‘The origin of eucrites, diogenites, and olivine diogenites: magma ocean crystallization and shallow magma processes on Vesta’ by B. E. Mandler and L. T. Elkins-Tanton. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 49, 468–472 (2014).

Jaumann, R. et al. The geological nature of dark material on Vesta and implications for the subsurface structure. Icarus 240, 3–19 (2014).

Kawabata, Y. & Nagahara, H. Crystallization and cooling conditions for diogenite formation in the turbulent magma ocean of asteroid 4 Vesta. Icarus 281, 379–387 (2017).

Lunning, N. G. et al. Olivine and pyroxene from the mantle of asteroid 4 Vesta. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 418, 126–135 (2015).

Lichtenberg, T. et al. Magma ascent in planetesimals: control by grain size. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 507, 154–165 (2019).

Young, E. D. et al. Near-equilibrium isotope fractionation during planetesimal evaporation. Icarus 323, 1–15 (2019).

Zhang, A. C. et al. Evidence of metasomatism in the interior of Vesta. Nat. Commun. 11, 1289 (2020).

Neumann, W., Breuer, D. & Spohn, T. Differentiation and core formation in accreting planetesimals. Astron. Astrophys. 543, A141 (2012).

Schubert, G., Turcotte, D. L. & Olson, P. Mantle Convection in the Earth and Planets (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001).

Yoshino, T., Walter, M. J. & Katsure, T. Core formation in planetesimals triggered by permeable flow. Nature 422, 154–157 (2003).

Cerantola, V., Walte, N. P. & Rubie, D. C. Deformation of a crystalline olivine aggregate containing two immiscible liquids: implications for early core-mantle differentiation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 417, 67–77 (2015).

Terasaki, H. et al. Percolative core formation in planetesimals. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 273, 132–137 (2008).

Pierazzo, E. & Melosh, H. J. Hydrocode modeling of oblique impacts: the fate of the projectile. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 35, 117–130 (2000).

Pierazzo, E. & Melosh, H. J. Melt production in oblique impacts. Icarus 145, 252–261 (2000).

Davison, T. M. et al. The effect of impact obliquity on shock heating in planetesimal collisions. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 49, 2252–2265 (2014).

Ricard, Y., Sramek, O. & Dubuffet, F. A multi-phase model of runaway core-mantle segregation in planeteary embryos. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 284, 144–150 (2009).

Rubie, D. C., Nimmo, F. & Melosh, H. J. in Treatise on Geophysics 2nd edn (ed. Schubert, G.) 43–79 (Elsevier, 2015).

Melosh, H. J. Impact Cratering: A Geological Process (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

Schenk, P. et al. The geologically recent giant impact basins at Vesta’s south pole. Science 336, 694–697 (2012).

Williams, D. A. et al. Lobate and flow-like features on asteroid Vesta. Planet. Space Sci. 103, 24–35 (2014).

Borisov, A., Palme, H. & Spettel, B. Solubility of palladium in silicate melts: implications for core formation in the Earth. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 705–716 (1994).

Shakura, N. I. & Sunyaev, R. A. Black holes in binary systems. Observational appearance. Astron. Astrophys. 24, 337–355 (1973).

Daly, R. T. & Shultz, P. H. Predictions for impactor contamination on Ceres based on hypervelocity impact experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7890–7898 (2015).

Daly, R. T. & Shultz, P. H. Delivering a projectile component to the Vestan regolith. Icarus 264, 9–19 (2016).

Daly, R. T. & Schultz, P. H. Projectile preservation during oblique hypervelocity impacts. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 1364–1390 (2018).

Ivanov, B. A. & Melosh, H. J. Two-dimensional numerical modeling of the Rheasilvia impact formation. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 1545–1557 (2013).

Thompson, S. L. & Lauson, H. S. Improvements in the CHART D Radiation-Hydrodynamic Code III: Revised Analytic Equations of State SC-RR-71 0714 (Sandia National Laboratory, 1972).

Greenwood, R. C. et al. Widespread magma oceans on asteroidal bodies in the early Solar System. Nature 435, 916–918 (2005).

Marchi, S. et al. Small crater populations on Vesta. Planet. Space Sci. 102, 96–103 (2014).

Collins, G. S., Melosh, H. J. & Ivanov, B. A. Modeling damage and deformation in impact simulations. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 39, 217–231 (2004).

Morbidelli, A. et al. A plausible cause of the late heavy bombardment. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 371–380 (2001).

Bottke, W. F. et al. Can planetesimals left over from terrestrial planet formation produce the lunar late heavy bombardment? Icarus 190, 203–223 (2007).

Barboni, M. et al. Early formation of the Moon 4.51 billion years ago. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602365 (2017).

Broz, M. et al. Constraining the cometary flux through the asteroid belt during the late heavy bombardment. Astron. Astrophys. 551, A117 (2013).

Bottke, W. F. et al. Velocity distribution among colliding asteroids. Icarus 107, 255–268 (1994).

Gault, D. E. & Wedekind, J. A. Experimental studies of oblique impact. In Proc. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference Vol. 3 3843–3875 (1978).

Kendall, J. D. & Melosh, H. J. Differentiated planetesimal impacts into a terrestrial magma ocean: fate of the iron core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 448, 24–33 (2016).

Rohlen, R. et al. The fate of iron cores upon impact of differentiated bodies into magma oceans. In Proc. 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 1854 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2021).

Spudis, P. D. The Geology of Multi-Ring Basins (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993).

Elbeshausen, D., Wünnemann, K. & Collins, G. S. Scaling of oblique impacts in frictional targets: implications for crater size and formation mechanisms. Icarus 204, 716–731 (2009).

Jaumann, R. et al. Vesta’s shape and morphology. Science 336, 687–690 (2012).

Walker, R. J., Horan, M. F., Shearer, C. K. & Papike, J. J. Low abundances of highly siderophile elements in the lunar mantle: evidence for prolonged late accretion. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 224, 399–413 (2004).

Kruijer, T. S. et al. The early differentiation of Mars inferred from Hf–W chronometry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474, 345–354 (2017).

Dauphas, N. & Pourmand, A. Hf–W–Th evidence for rapid growth of Mars and its status as a planetary embryo. Nature 473, 489–492 (2011).

Ivanov, B. A. Mars/Moon cratering rate ratio estimates. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 87–104 (2001).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Burgess, S. & Yin, Q. –Z. The lunar magma ocean: reconciling the solidification process with lunar petrology and geochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 304, 326–336 (2011).

Puchtel, I. S. et al. Osmium isotope and highly siderophile element systematics of lunar impact melt breccias: implications for the late accretion history of the Moon and Earth. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3022–3042 (2008).

Liu, J. G. et al. Diverse impactors in Apollo 15 and 16 impact melt rocks: evidence from osmium isotopes and highly siderophile elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 155, 122–153 (2015).

Gleißner, P. & Beck, H. Formation of Apollo 16 impactites and the composition of late accreted material: constraints from Os isotopes, highly siderophile elements and sulfur abundances. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 200, 1–24 (2017).

Jedicke, R., Larsen, J. & Spahr, T. in Asteroids III (eds Bottke, W. F. et al.) 71–88 (Univ. Arizona Press, 2002).

Benz, W. et al. The origin of the Moon and the single-impact hypothesis III. Icarus 81, 113–131 (1989).

Potter, R. W. K. et al. Constraining the size of the South Pole–Aitken Bsin impact. Icarus 220, 730–743 (2012).

Neumann, W. et al. Modeling the evolution of the parent body of acapulcoites and lodranites: a case study for partially differentiated asteroids. Icarus 311, 146–169 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the developers of iSALE (www.isale-code.de), in particular D. Elbeshausen for developing the iSALE-3D. M.-H.Z. is supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macau (0079/2018/A2). K.W., H.B., G.J.A., N.A. and M.-H.Z. acknowledge funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 263649064 – TRR 170. This is TRR publication no. 137. W.N. acknowledges support by Klaus Tschira foundation. J.M.D.D. acknowledges support by NASA Emerging Worlds programme (80NSSC19K0932).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.-H.Z. and A.M. conceived the idea and discussed every step of this work. M.-H.Z. performed the impact simulations and Monte Carlo modelling with discussion with N.A. and K.W. W.N. performed the thermal evolution simulation. W.N., D.C.R., Q.-Z.Y., A.M. and M.-H.Z. discussed the HSE transports in Vesta. M.-H.Z., A.M., J.M.D.D., G.J.A., H.B. and Q.-Z.Y. analysed the measured HSE datasets and calculated the late-accreted mass to Vesta. The manuscript was written by M.-H.Z. and A.M. with detailed reviews and contributions by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Astronomy thanks Mario Fischer-Gödde, Simone Marchi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Parameters of the exponent functions (f = a*exp(−b*x)) for the fit of impactor retention ratio derived from the oblique impact simulations.

Here x represents the ratio of diameter between impactor and Vesta.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cumulative number of impactors with diameters larger than 1 km colliding with Vesta and the size-frequency distribution of the impactors.

The details of estimating the cumulative impactor (d > 1 km) number as a function of time are discussed in the Methods. In (a), the black line represents the combined estimates of the number of impactors from the main belt (green line) and the leftover planetesimals from the terrestrial planet region (red line). Here, we did not include any cometary contribution to the bombardment that may have been delivered to Vesta during the migration of the giant planets. In (b), the data points represent the incremental size-frequency distribution for the current main belt that is derived from the absolute magnitude distribution (see refs. 30,127,128,129).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Average impactor retention ratio as a function of the integrated time for three impact scenarios of Vesta.

The average impactor retention ratio is defined as the ratio between the total mass accreted to Vesta and total impactor mass colliding with Vesta. Each data point represents the average impactor retention ratio for impacts occurring cumulatively from a start time to the present day. The average impactor retention ratios for three impact scenarios are almost similar within a range between 0.065 and 0.075 (shadow area) and do not vary significantly within the considered time interval from the present day to the start time between 4,100 Ma and 4560 Ma.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Vesta’s thermal evolution for shallow magma ocean and global magma ocean scenarios.

The thermal evolution is calculated with partitioning of 26Al for shallow magma ocean (a), but without the partitioning of 26Al for the global magma ocean (c). (b) is a zoom into Vesta’s subsurface with the shallow magma ocean (a) showing a life-time of ~ 0.07 Myr and a depth of a few hundred metres. In each panel, the horizontal axis represents the time since CAI formation, whereas the vertical axis represents the radius variation during the thermal evolution. Vesta was assumed to accrete instantaneously and form an initially porous structure with a larger size, then underwent sintering from an unconsolidated and highly porous state to a consolidated state arriving at the current asteroid size thereafter (see ref. 85). For the shallow magma ocean scenario, the mantle crystallizes completely within ~ 200 Myr after CAI formation, when the temperature falls below the silicate solidus of ~ 1425 K (a). For the global magma ocean scenario, complete mantle crystallization occurs within ~ 300 Myr after CAI formation (c). The model is from Neumann et al.40, with the parameters adopted for the calculation of melting and heat sources from Neumann et al.130.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Source data

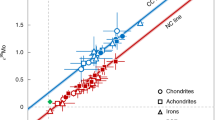

Source Data Fig. 1

The HSE data source of HED meteorites for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

The individual impactor retention ratio from the iSALE simulation.

Source Data Fig. 3

The cumulative accreted mass for different bombardment models.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

The HSE data source of lunar samples for Extended Data Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, MH., Morbidelli, A., Neumann, W. et al. Common feedstocks of late accretion for the terrestrial planets. Nat Astron 5, 1286–1296 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01475-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01475-0

This article is cited by

-

Terrestrial planet and asteroid belt formation by Jupiter–Saturn chaotic excitation

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Vesta’s many ties to Earth

Nature Astronomy (2021)