Abstract

Cell-cultivated meat and seafood is getting closer to a reality for consumers in the US and around the world. However, regulators are still largely lagging behind on regulating production and labelling of these products. In a large experimental study using a representative US sample (N = 2653), we tested 9 different names for 3 different types of meat and seafood products in terms of their clarity, consumer appeal, and communication of safety and allergenicity. We found that terms proposed by the conventional meat and seafood industry including ‘artificial’ and ‘lab-grown’ tended to score low in terms of consumer appeal, purchase intent, and perceived safety, while ‘artificial’ also had the lowest score on clarity and communicating allergenicity. On the other hand, terms proposed by the cell-cultivated industry including ‘Novari’ scored high in terms of appeal and purchase intent but scored low in terms of clarity. The terms ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-cultivated’ were the best all round labels in terms of clarity, appeal, and communicating safety and allergenicity – in particular, the addition of the prefix ‘cell-’ increased understanding compared to ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’ labels. The most-understood label was a short descriptive phrase (‘grown from [animal] cells, not farmed [or fished]’), suggesting that additional wording on packaging could aid consumer understanding in this early stage. A high proportion of consumers were uncertain about the allergen status of cell-cultivated products under all names, suggesting that cell-cultivated products should be labelled as the type of meat they are, and carry applicable allergen information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cultivated protein industry has received growing attention in recent years due to rising investment, technological advancement, and progress towards reaching price parity with conventional animal protein. Cultivated protein aims to address the negative externalities increasingly associated with conventional, intensive animal agriculture — including global environmental degradation, dangers to human health, biodiversity loss, and moral concerns.

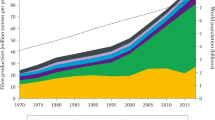

Global emissions from livestock production contribute over 14% of global greenhouse gases1, while the fishing industry represents 4% of global food emissions2. Research demonstrates that cultivated meat may combat these consequences, with cultivated chicken, pork, and beef potentially reducing GHG emissions by 17%, 52%, and 85–92%, respectively, compared to their conventionally produced counterparts3.

Human health is directly impacted by conventional livestock production, with over 36% of emerging zoonotic diseases associated with animals intended for human consumption4. These zoonotic diseases significantly impact human health, livelihood, and, as revealed in the Covid-19 pandemic, global economic resilience5,6,7. Microplastics and mercury in seafood present credible threats to public health8,9,10,11,12. The use of prophylactic antibiotics in animal agriculture and aquaculture also exacerbates antimicrobial resistance, again presenting a threat to public health13,14,15,16. Cultivated proteins are produced in a controlled environment, which may significantly reduce the risk of transmission of zoonotic diseases, remove the need for antibiotics, and minimize the potential of microplastic and other foreign contaminants.

Livestock production and the global fishing industry directly contribute to biodiversity loss, with livestock production accounting for an estimated 30% of human-induced biodiversity loss17,18,19. Aquatic populations have seen a steep decline over the last few decades affecting biodiversity and leading to the breakdown of aquatic ecosystems20,21. Cultivated protein production is estimated to utilize 95% less land and 78% less water than conventionally produced meat, significantly reducing the impact on biodiversity3 above3.

Finally, profound ethical issues are associated with conventional livestock, commercial fishing, and aquaculture. Vast fishing vessels decimate fish populations, which coastal subsistence communities depend upon for food22. Recorded human rights infringements and modern slavery are well-documented in the industrialized fishing industry23 and intensive animal production24. These industries also, of course, harm the animals in question.

Despite well-documented negative externalities, the conventional protein industry plays a vital role in the global economy and food security. Livestock contributes to 17% of global kilocalorie consumption25 while fishing and aquaculture support 60 million jobs and 3 billion rely on fish as their primary protein intake26. Despite a shift toward alternative proteins, projections indicate global animal protein consumption will increase in the next decade by 14% by 2030 (compared to base period average of 2018–2020)27 exacerbating the existing externalities associated with conventional protein production28,29.

As cultivated protein reaches the global market, these novel protein products will exist alongside conventional animal products. Livestock and fishing interest groups and associations have expressed reasonable concern about enabling consumers to distinguish cultivated protein from traditional proteins. At the core of the discussion is nomenclature. To date, stakeholders have struggled to reach a consensus on what to call these products30,31,32. The terminology debate centers around consumer appeal and understanding within the cultivated protein industry. The traditional protein industry expresses similar considerations, with the additional requirement that nomenclature refrains from potentially condemning terms such as “clean”33. The adoption of a consistent nomenclature is crucial in bringing cultivated protein products to the commercialized market. Accordingly, this paper seeks to add to the nomenclature discussion on meat, chicken, and fish.

Since the introduction of the first cultivated beef burger in 2013, the nomenclature discussion has been distinguished by varying levels of consensus among stakeholders. Precise labeling is essential to commercializing novel foods as consumers must feel comfortable with the product and understand its origins. Beyond consumer acceptance/understanding, consideration must be given to regulatory frameworks, industry preferences, and interest group feedback. Accordingly, there has yet to be stakeholder consensus as reflected in a recent USDA request for information, which resulted in 39 terms put forward34.

Early academic and industry leaders referred to the product as “in-vitro”35,36, though usage has declined due to consumer associations with artificiality37. “Lab-grown” may be less attractive to consumers for potentially similar reasons38. The terminology “cultured” is well- utilized39 and is relatively well-received by both consumers38,40,41 and industry leaders42. Good Meat, the only company currently authorized to sell cultivated meat, has used ‘cultured’ in its advertising campaigns43. However, “cultured” is associated with aquaculture production and may be misleading in the context of seafood44. Consumer studies indicate that consumers responded favorably to “clean meat”38,45 and ‘slaughter-free” nomenclature40. However, other stakeholders may not consider this nomenclature optimal, specifically conventional animal protein producers33. While “cell-based” has been presented as a compromising term supported by industry leaders and organizations such as the North American Meat Institute, it received low consumer appeal ratings32,44. The terminology “cultivated” has been increasingly popularized and is now the preferred terminology utilized by entities such as the Good Food Institute46. In 2021, industry leader research indicated that 75% of cultivated protein companies preferred “cultivated” terminology42.

While preferred terminology is still the subject of debate, products are increasingly making their way to market. In December 2020, Singapore approved the first cultivated meat product for sale47, reinforcing the importance of nomenclature consensus in the United States and abroad. In recent years there have been two federal calls for feedback in the United States: (1) the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) 2020 call for feedback on labeling foods comprised of cultivated seafood, and (2) the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 2021 call for comments on the labeling of cultivated meat and poultry.

In October 2020 the FDA issued a Request for Information to solicit feedback to support the naming of cell-cultivated fish products. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires that all foods have a label depicting a “common or usual name.” The regulation, 21CFR101.3, requires that the “common or usual name” accurately identifies and describes the product in the most direct and straightforward terms possible to ensure informed customer decisions48. In 2020, the FDA called for labelling comments, encouraging discourse on cell-cultivated seafood labelling49. Previous research on nomenclature has primarily focused on consumer acceptance rather than identifying a common or usual name that may be regulated by the FDA38.

Currently, at least two research papers have examined cultivated seafood nomenclature specifically regarding FDA requirements, both by the same authors. The first study30 utilised an online between-subject experiment to test common or usual names using packages of three types of seafood consumers may expect to encounter in the supermarket. In the study, 3186 U.S. adults read the terms “cell-cultured seafood,” “cultivated seafood,” “cell-based seafood,” “cultured seafood,” as well as the phrase, “produced using cellular aquaculture“30. The study determined that “cell-based seafood” performed the best out of the names tested concerning clarity, distinctiveness, allergen signaling, and consumer appeal. The second study31 built on the first and assessed just two names (“cell-based seafood” and “cell-cultured seafood”) in a sample of 1200 U.S. adults. The authors found that both names enabled most consumers to correctly identify the nature of the products and their potential allergenicity and therefore met the FDA’s key criteria. Interestingly, this study found that the name “cell-based seafood” outperformed “cell-cultured seafood” concerning positivity of overall impressions, positivity of initial thoughts and feelings, and interest in tasting and purchasing. Of the 35 comments the FDA received in response to their feedback request, 24% of the comments the FDA received cited one or both of the Hallman and Hallman studies50.

In 2021, the USDA issued a request for information soliciting suggestions for the labeling of cell-cultivated meat and poultry which would address consumer expectations for the products, not be false or misleading, and consider economic data. The agency received an influx of responses. A review of the responses indicates the nomenclature suggestions reflected the lack of consensus across stakeholder groups34,51 (Table 1) (Removed nomenclature that had only one suggestion).

The term ‘cultivated’ had the highest percentage of suggestions and drew support primarily from cell-based meat companies34. These results align with research produced by the Good Food Institute in 2021 —identifying that 75% of cell-based meat technology companies preferred the ‘cultivated’ nomenclature42. However, some in opposition to the term thought ‘cultivated’ presented “ambiguity” and suggested ‘lab-grown’ as an alternative (a suggestion from a beef industry group)34.

‘Cell-cultured’ drew approval from varied interest groups, with traditional protein industry groups such as National Fisheries Institute, National Chicken Council, and Idaho Cattle Association aligning with cultivated technology groups such as BlueNalu and Biomilq34. The animal interest group Animal Legal Defence Fund also advocated for this terminology34. Nomenclature including “Cultured” had a 20% adoption rate by cultivated meat technology organisations in GFI’s 2021 study42.

Traditional meat industry groups/advocates primarily suggested ‘lab-grown’ nomenclature34. However, ‘lab-grown’ may prompt negative associations and disgust, as cited in previous consumer-based studies38. Therefore, the adoption of “lab-grown” by cell-cultivated meat companies is unlikely. The term “artificial,” also suggested solely by traditional meat industry interest groups34, has similar negative connotations and may unintentionally mislead consumers into assuming cultivated protein products do not contain meat. Our consumer survey includes both ‘lab-grown’ and ‘artificial.’

Ultimately, a primary concern of both the cultivated and traditional meat industry is consumer awareness and the ability to differentiate cultivated protein from traditionally produced protein accurately.

This research uses preferred nomenclature identified in recent FDA and USDA feedback requests and consumer survey data to test nomenclature against consumer understanding, appeal, willingness to purchase, and awareness of allergenicity. The present study builds on Hallman and Hallman’s30,31 work by presenting consumers with “cell-based” and “cell- cultured” alongside preferred nomenclature gleaned from the USDA’s call for feedback and the addition of a new term, “Novari.” A review of all terms included in our consumer study (Table 2) and the rationale for inclusion is listed below. This is also the first study, to the authors’ knowledge, to test the viability of terms for both cell-cultivated meat and seafood.

Results

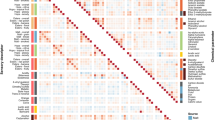

In this section, we present the results of the experiment for the 9 different labels for beef, chicken, and salmon products. Participants were allocated independently and at random to one of 9 labels and one of 3 products, yielding the following sample sizes for each condition (Table 3):

Understanding of product

Our first set of analyses focused on correct understanding of the different labels. Here, we show the percentage of consumers in each condition identifying the nature of the product correctly, incorrectly, or answering don’t know (Figs. 1–3).

As shown, the highest proportion of consumers correctly identified the nature of cell-cultivated products under the names ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’, ‘cell-based’, ‘lab grown’, and the descriptive phrase. These labels were correctly understood by more than 80% of consumers for beef, chicken, and salmon.

The labels ‘cultivated’, ‘cultured’, and ‘artificial’ were less well-understood, being correctly identified by 33–62% of consumers for beef, chicken, and salmon. While ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ were incorrectly identified by 13–28% of beef and chicken consumers, this rose to 19–46% of salmon consumers. This is likely due to the conflation of these terms with aquaculture. Moreover, the term ‘artificial’ was misunderstood by 21–40% of beef, chicken, and salmon consumers, and was often incorrectly interpreted as referring to plant-based products.

Finally, the label ‘novari’ was the least well-understood label, being correctly identified by just 0–3% of consumers. While the proportion of people incorrectly understanding this term was relatively low (18–25%), the proportion of consumers who said they did not know what the term referred to was higher than any other term (72–82%). This indicates that the term ‘novari’ was unfamiliar, and did not communicate much information about the nature of the product.

Chi square analyses indicated a significant difference in the proportion of respondents giving each answer for beef (<2(16) = 366.844, p < 0.001), chicken (<2(16) = 429.085, p < 0.001), and salmon (<2(16) = 514.390, p < 0.001).

Pairwise comparisons are indicated in Table 4. Superscript letters indicate that the value differs significantly from the condition labelled with the same letter in the leftmost column.

Appeal, purchase intent, and perceived safety

In this section, we report the mean scores for each product’s appeal, purchase likelihood, and perceived safety (understanding of risk for individuals who are not allergic to the given type of meat) (Figs. 4–6).

As shown, the term ‘novari’ was associated with the highest levels of appeal, purchase intent, and perceived safety for beef, chicken, and salmon. Conversely, the term ‘artificial’ was associated with the lowest levels of appeal and purchase intent for beef, chicken, and salmon, and the lowest level of perceived safety for beef and salmon (for chicken, ‘lab-grown’ was associated with the lowest level of perceived safety).

For beef and salmon, ‘cultivated’ was perceived more positively than ‘cultured’ and ‘cell-based’, whereas for chicken, ‘cultured’ was perceived slightly more positively than ‘cultivated’. Generally, adding the prefix ‘cell-’ to the terms ‘cultured’ and ‘cultivated’ increased understanding, but decreased consumer appeal and perceived safety.

ANOVA analyses indicated that there were significant differences between labels in appeal for beef (F(8,873) = 3.348 p = 0.001), chicken (F(8,881) = 10.193 p < 0.001), and salmon (F(8,872) = 13.742 p < 0.001).

There were also significant differences between labels in purchase likelihood for beef (F(8,873) = 2.256 p = 0.022), chicken (F(8,881) = 8.084 p < 0.001), and salmon (F(8,872) = 8.297 p < 0.001).

Finally, there were significant differences between labels in perceived safety for chicken (F(8,736) = 4.113 p < 0.001) and salmon (F(8,748) = 4.337 p < 0.001), but not for beef (F(8,738) = 1.100 p = 0.361).

Pairwise comparisons are indicated in Table 5. Superscript letters indicate that the value differs significantly from the condition labelled with the same letter in the leftmost column.

Malerich & BryantNomenclature Study

Perceived safety for allergy-sufferers

Here, we report on the percentage of people who thought that products under each label were safe for people who are usually allergic to the given type of meat (Figs. 7–9).

As shown, the term ‘novari’ was generally associated with the highest proportion of consumers correctly identifying that the product was not suitable for allergy-sufferers. Between 69–89% identified products with this label as unsafe for allergy-sufferers, while 0–2% incorrectly said it would be safe.

The term ‘artificial’ was associated with the highest proportion of consumers incorrectly saying that the products would be safe for allergy-sufferers (11–27%), the lowest proportion of consumers correctly saying that the products would not be safe for allergy- sufferers (16–30%) and the highest proportion of consumers being uncertain about the allergy safety status (58–64%). This is likely due to the misleading nature of this label indicating that the products are not beef, chicken, and salmon, respectively, and thus causing consumers to infer that they would be safe for people who are usually allergic to those products.

The proportion of consumers who correctly identified products as unsuitable for allergy-sufferers was similar for the other labels for most products. The terms ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’, ‘cultured’, ‘cell-based’, ‘lab-grown’ and the descriptive phrase were correctly perceived as unsafe for allergy-sufferers by 38–66% of consumers who saw beef or chicken. The terms ‘cultivated’ and ‘cultured’ were perceived as unsafe for allergy- sufferers by 75–80% of those who saw salmon products, presumably because they were more often misunderstood as referring to aquaculture-produced salmon. Indeed, the overall rate of people identifying salmon products as unsafe for allergy-sufferers was higher, presumably because seafood allergies are far more common than chicken/beef allergies.

Chi square analyses indicated that the proportion of consumers in each category differed significantly between naming conditions for beef (<2(16) = 127.036, p < 0.001), chicken (<2(16) = 74.389, p < 0.001), and salmon (<2(16) = 136.693, p < 0.001).

Pairwise comparisons are indicated in Table 6. Superscript letters indicate that the value differs significantly from the condition labelled with the same letter in the leftmost column.

Comparing types of meat

We employed an additional ANOVA analysis to compare purchase intent across labels between the three different types of meat presented. The results are shown in Fig. 10.

The ANOVA analysis found no significant differences in purchase intent (F(2,2650) = 2.292, p = 0.101) or perceived safety (F(2)2246 = 0.647, p = 0.524) between the three types of meat. However, there was a significant difference between the types of meat in terms of appeal (F(2)2650 = 3.852, p = 0.021) – in particular, salmon was rated as significantly more appealing than beef. For beef, 20% said they were somewhat or extremely likely to purchase; for chicken, 21.8% said they were somewhat or extremely likely to purchase; for salmon, 21.9% said they were somewhat or extremely likely to purchase.

It is noteworthy that these findings do not mirror those of previous studies, which have found cultivated beef to be more appealing than cultivated chicken, which was in turn found to be more appealing than cultivated fish52. It is also worth noting that these purchase intention rates are somewhat lower than those observed in previous studies; this may be due to the small amount of information given to participants, and due to the high inclusion of unappealing names.

Demographic predictors of purchase intent

We also employed multiple linear regression to investigate the demographic factors associated with purchase cell-cultivated meat and seafood purchase intent. The results are shown in Table 7. Note that, for categorical variables, the reference values are Gender=Male and Region=Northeast.

As shown, the regression identified two significant predictors of cell-cultivated meat and seafood purchase intent. Younger respondents were more likely to purchase cell-cultivated meat and seafood, whereas females were significantly less likely to purchase than males.

Discussion

In this study, we gathered the commonly-suggested names for cultivated meat to FDA and USDA requests for information, and tested them experimentally among a representative sample of US consumers to determine their clarity, consumer appeal, and communicativeness of safety.

One notable result observed here is that the short descriptive phrase achieved the greatest degree of understanding compared to all tested terms. Though there was no significant difference from the terms ‘cell-cultivated’, ‘cell-cultured’, and ‘lab-grown’, the descriptive phrase was the only term to achieve above 95% understanding across all types of meat tested. This may suggest that, at this stage of industry development, full descriptions are likely to be more informative than any labels for these unfamiliar products.

Names which invoke science and technology tended to have lower measures of appeal and purchase intent. This concurs with previous findings, which found that immediate associations were important in explaining differences in willingness to eat cultivated meat under different labels38. The label ‘lab-grown’, while generally well-understood, also tended to be associated with lower levels of consumer appeal and purchase intent. It was also associated with a higher level of uncertainty about the safety for allergic consumers.

The findings indicate that, while some terms were unclear, the addition of the prefix ‘cell-’ to ‘cultured’ or ‘cultivated’ improved clarity when describing these products. Previous research has indicated that the imagery of cultivation is a positive one in this context40 and this term is now associated with other industry verbiage (e.g. the process of cultivating meat, using cultivators to grow meat). Therefore, based on these data, the terms ‘cell-cultured’ or ‘cell- cultivated’ appear to be the most appropriate terms due to a high level of understanding, a relatively high level of consumer appeal and purchase intent, and a relatively high understanding that such products are not safe for allergy-sufferers.

It is also notable that there was a high degree of misunderstanding as to the allergenicity of cell-cultivated meat and seafood products, even for terms which were well-understood including the descriptive phrase. This misconception was especially high for products labelled as ‘artificial’, while it was lower for salmon products, for which allergies are more common compared to chicken and beef. Therefore, it is important that cell-cultivated meat and seafood products should be labelled as containing meat and seafood and should carry appropriate allergen warnings regardless of nomenclature.

This research adds to the discussion of Hallman and Hallman30,31, who assessed common or usual names for cell-cultivated seafood in their first study. Though they did not test the term ‘cell-cultivated’, they did find that the term ‘cell-cultured’ and the phrase ‘cultivated from the cells of’ were both seen as clear and appropriate, yet relatively unappealing. Ultimately, the study determined that ‘cell-based’ performed the best out of the names tested concerning distinctiveness, allergen signaling, and consumer appeal. The second study built on the first and assessed two names (‘cell-based’ and ‘cell-cultured’), finding that ‘cell-based’ outperformed ‘cell-cultured’. Our findings do not concur here – we find that ‘cell-cultured’ and ‘cell-cultivated’ tend to achieve the best levels of understanding, appeal, and clarity regarding allergenicity overall.

These findings have implications for manufacturers of cell-cultivated meat and seafood products and for regulators. In the United States, the FDA (21CFR102.5) requires a ‘common or usual name’ which ‘shall accurately identify or describe, in as simple and direct terms as possible, the basic nature of the food or its characterizing properties or ingredients’48. Therefore, a consumer’s ability to easily and accurately identify a product is crucial in establishing a common or usual name.

Cell-cultivated meat may be comparable in most respects (allergen status, nutritional content, taste, etc.) to conventionally produced meat. The distinguishing factor, or ‘characterizing property’, is the production method (rather than the ingredients) and the product name should therefore reflect this. Among the names tested in this study, ‘cell-cultivated’ had the optimal balance of achieving both clarity of product ingredients and consumer appeal. In addition to clarity of product and production, consumers must also be aware of allergens. In our study, consumers were uncertain about the product’s allergen status, and therefore, in the interest of food safety, cell-cultivated meat and seafood ought to be appropriately labeled with meat and seafood allergen information. The FDA requires labeling on all packaged allergen-containing foods, including single-ingredient products such as packaged meat and fish53. Therefore, cell- cultivated meat and seafood, which will contain allergens, will likely be required to carry an allergen-signaling label. Furthermore, categorizing cell-cultivated meat/seafood as something other than meat/seafood could cause consumers significant confusion with respect to allergenicity.

Our analysis indicated no clear consensus on an established common or usual name for cell-cultivated products. As cell-cultivated products gain market prominence, consumer awareness is likely to rise — leading to a better understanding of the products and the emergence of a distinct common or usual name that allows consumers to distinguish between cell-cultivated and conventionally produced products. However, for now, general public awareness of cell-cultivated meat and seafood and related technology is minimal. Accordingly, our research illustrates that a descriptive phrase was more successful in consumers accurately identifying the product than any of the exploratory terms. While such phrases are likely too long to be used in the nomenclature per se, their use on packaging alongside a product name could improve understanding and appeal.

There are some key limitations to be acknowledged in this study. First, self-reported online survey results are imperfect in terms of validity and reliability. While findings are therefore unlikely to be perfectly replicated in real food purchase decision situations, we did take some measures to increase validity, such as using attention checks to exclude poor quality responses and using realistic images of product packaging. Second, the Prolific survey platform acknowledges that participants will be subject to some selection bias based on response time, interest, study pricing, and other factors54. However, we attempted to mitigate these biases by using a large nationally-representative sample, and employing a robust series of quality and attention checks.

Future research could investigate the possibility of an as-yet-undiscovered term for cell- cultivated meat and seafood which is both appealing and intuitive. We tested the novel term ‘Novari’ in this study and found that it achieved the former but not the latter. Research could also explore which specific forms of regulatory approval and on-package labels would be most reassuring to consumers who are considering trying cell-cultivated meat and seafood. Social research could also explore the types of cell-cultivated meat and seafood dishes consumers will find most appealing, in order to guide product development. Another promising area for future research is the impact of additional information about products and processing on purchase intent — in this study, very little information was given by design. Finally, future studies could assess the interaction between a combination of a proposed common or usual name and a short descriptive phrase - i.e. the descriptive phrase could supplement understanding alongside a name.

As we have argued in this paper, widespread adoption of these products could yield significant benefits for the planet. Cell-cultivated meat and seafood offer a substitute for conventional meat and seafood consumption, potentially mitigating many negative impacts of the conventional meat and seafood industries. Consumers are more aware than ever of food choice implications and have expressed a willingness to transition to more sustainable options, including cell-cultivated options55.

Cell-cultivated meat and seafood companies in the United States and globally have successfully produced a variety of prototype products — pending regulatory approval. A recent multinational study indicates that regulatory feedback may increase consumer acceptance of cultivated meat56 reinforcing the necessity for regulatory frameworks to embrace a cohesive narrative around these novel products, including naming. Regulatory approval in one nation may influence other nations, as Singaporean regulation of cell- cultivated chicken in 2020 incited speculation about regulatory approval in other countries. Currently, there are pathways for regulatory approval in nations across the globe and the European Union42. Additionally, with cross-national partnerships such as those between cultivated meat company Aleph Farms (Israel) with BRF (Brazil) and Mitsubishi (Japan), nomenclature cohesivity may be required for packaging and marketing, incentivizing expedited regulatory decisions in multiple countries at once57,58. Industry leaders, investors, and policymakers suggest a 1–5 year timeline for wide-scale market availability59. Thus, there is an urgency to address regulatory issues (such as adopting a common or usual name) as regulations may lag behind consumer demand and industry innovation. If we achieve the necessary advancements in technology and regulation, cell-cultivated meat and seafood can secure great improvements in animal treatment, environmental outcomes, and public health.

Methods

To test the feasibility of a range of different names, we conducted an online experimental survey with a representative sample of US consumers. This study received ethical approval from the University of Bath Psychology Research Ethics Committee (PREC 22–100). Respondents provided written informed consent to take part in the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited through the online research platform, Prolific, and were each paid $1.00 for their participation in a 5-minute survey. We tested 9 different labels for each of 3 different products, yielding a total of 27 unique experimental conditions. In order to ensure sufficient power for comparisons between all conditions, we recruited 2700 participants. We recruited a total of 2,708 participants, and removed 55 of them, yielding a final sample of 2653 participants. Participants were removed for various reasons, including unfinished responses, speeding, not giving consent, failing attention check questions, and being under the age of 18.

We aimed to recruit a representative sample of US consumers, and to this end, we employed a stratified sampling approach, recruiting proportional numbers of males and females in the age brackets 18–29, 30–44, 44–59, and 60+. The proportion of participants belonging to each age/gender group is represented in Fig. 11:

Procedure

Participants were recruited through Prolific and directed to the survey, which was hosted on Qualtrics. First, participants read information about the study and gave their consent to take part. After completing a CAPTCHA to verify human responses, they were randomly allocated to one of 3 types of meat, and one of 9 product labels (see Table 8).

They saw an image of food packaging corresponding to the labels above, and answered a series of questions about the product they saw. They were asked to identify what the product was based on what the packaging communicated about the product — whether it was hunted/fished in the wild, farm raised, produced by animal cells in a food facility, or was plant-based. They could also indicate that they don’t know.

Participants were also asked how likely they would be to purchase the product (5 point scale; Extremely unlikely – Extremely likely), and how appealing they found the product (5 point scale; Not at all appealing – Very appealing). Next, they were asked whether it would be safe to eat the product for someone who was allergic to the meat usually (Yes, No, Don’t know), and how safe it would be to eat for someone who was not allergic to the meat usually (5 point scale; Very unsafe – Very safe, or Don’t know).

In the last section of the survey, participants answered demographic questions about themselves, including gender, age, income, and US region. There were also 2 quality control questions throughout the survey: in one question, participants had to choose ‘I am a human and I am paying attention’ from a list of four options, and in the second question, they had to choose ‘Yellow’ from a list of five colours. Those who failed either attention check were removed from the survey. Finally, participants were thanked for their participation, debriefed, and received payment through Prolific.

Materials

Images used were adapted from those found via copyright-free searches on Google Images. The original images had Creative Commons licences on the website world.openfacts.org (see Fig. 12).

As well as testing a variety of labels for these products, we also included a descriptive term, which succinctly describes the product — ‘Grown from [animal] cells, not farmed [or fished]’. This term was included as a benchmark for the other names in terms of product understanding and appeal, and provided an additional level of comparison to the research conducted by Hallman and Hallman30,31.

The full survey instrument is included in the Appendix A.

Analyses

In order to compare the impact of different labels on consumer perceptions of cell-cultivated beef, chicken, and salmon, we employed a series of ANOVA and chi square analyses. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 26. All differences were considered statistically significant where p < 0.05.

Appeal, purchase likelihood, and safety were rated on 1–5 scales, and were compared between naming conditions using a series of one-way ANOVAs within each product category. Pairwise differences were assessed using Tukey’s HSD. Product identification and perceived safety for allergy-sufferers were both assessed using categorical measures and were compared between naming conditions using chi square analyses within each product category.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, C.B., upon request.

Change history

13 January 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-023-00177-3

References

Gerber, P. J. Tackling climate change through livestock – a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. xii. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2019).

Parker, R. W. et al. Fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions of world fisheries. Naturse Clim. Change 8, 333–337 (2018).

Sinke, P. & Odegard, I. LCA of cultivated meat - CE delft. (2021). Available at: https://cedelft.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/04/CE_Delft_190107_LCA_of_cultivated_meat_Def.pdf (Accessed: November 2022).

Otte, J. & Pica-Ciamarra, U. Emerging infectious zoonotic diseases: the neglected role of food animals. One Health 13, 100323 (2021).

Karesh, W. B. et al. Ecology of zoonoses: natural and unnatural histories. Lancet 380, 1936–1945 (2012).

Rohr, J. R. et al. Emerging human infectious diseases and the links to Global Food Production. Nat. Sustainability 2, 445–456 (2019).

Rahman, M. T. et al. Zoonotic diseases: etiology, impact, and control. Microorganisms 8, 1405 (2020).

Farrell, P. & Nelson, K. Trophic level transfer of microplastic: Mytilus edulis (L.) to carcinus maenas (L.). Environ. Pollut. 177, 1–3 (2013).

Rochman, C. M. et al. Anthropogenic debris in seafood: plastic debris and fibers from textiles in fish and bivalves sold for human consumption. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–3 (2015).

Lusher, A. L., Mendoza-Hill, P. C. H. & Hollman, J. J. Microplastics in fisheries and aquaculture: status of knowledge on their occurrence and implications for aquatic organisms and food safety. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. (No. 615). (2017).

Mattsson, K., Jocic, S., Doverbratt, I. & Hansson, L.-A. Nanoplastics in the aquatic environment. In Microplastic Contamination In Aquatic Environments. 379–399 (2018).

Costa, E. et al. Trophic transfer of microplastics from copepods to jellyfish in the marine environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 8, 4–5 (2020).

Kirchhelle, C. Pharming Animals: a global history of antibiotics in food production (1935-2017). Palgrave Commun. 4, 1–13 (2018).

Miranda, C. D., Godoy, F. A. & Lee, M. R. Current status of the use of antibiotics and the antimicrobial resistance in the Chilean Salmon Farms. Front. Microbiol. 9, 10–11 (2018).

Pearson, M. & Chandler, C. Knowing antimicrobial resistance in practice: a multi-country qualitative study with human and Animal Healthcare Professionals. Glob. Health Action 12, 1599560 (2019).

Schar, D. et al. Twenty-year trends in antimicrobial resistance from aquaculture and fisheries in Asia. Nat. Commun. 12, 6–8 (2021).

Westhoek, H. et al. The Protein Puzzle: The consumption and production of meat, dairy and fish in the European Union. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (2011).

Maxwell, S. L., Fuller, R. A., Brooks, T. M. & Watson, J. E. Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 536, 143–145 (2016).

Morand, S. Emerging diseases, livestock expansion and biodiversity loss are positively related at global scale. Biol. Conserv. 248, 108707 (2020).

Pauly, D. & Zeller, D. Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nature Communications 7, 2–8 (2016).

Pauly, D. & Zeller, D. Comments on FAOs State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (Sofia 2016). Mar. Policy 77, 176–181 (2017).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. 55 (2018).

Lewis, S. G., Alifano, A., Boyle, M. & Mangel, M. Human rights and the sustainability of fisheries. Conservation for the Anthropocene Ocean 379–396 (2017).

Blattner, C. E. & Ammann, O. Agricultural Exceptionalism and Industrial Animal Food Production: Exploring the Human Rights Nexus. J. Food Law Policy 15, 11–12 (2020).

Herrero, M., Thornton, P. K., Gerber, P. & Reid, R. S. Livestock, livelihoods and the environment: understanding the trade-offs. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability 1, 111–120 (2009).

Howard, P. & IPES Food. The Politics of Protein: Examining Claims About Livestock, Fish, “Alternative Proteins” and Sustainability. 4 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022–2030. 163–164 (2022).

McLeod, A. World livestock 2011-livestock in food security. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2011).

Godfray, H. C. et al. Meat Consumption, health, and the environment. Science 361, 2–3 (2018).

Hallman, W. K. & Hallman, W. K. An empirical assessment of common or usual names to label cell‐based Seafood Products. J. Food Sci. 85, 2267–2277 (2020).

Hallman, W. K. & Hallman, W. K. A comparison of cell‐based and cell‐cultured as appropriate common or usual names to label products made from the cells of fish. J. Food Sci. 86, 3798–3809 (2021).

Ong, S., Choudhury, D. & Naing, M. W. Cell-based meat: current ambiguities with nomenclature. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 102, 223–231 (2020).

Greene, J. L., & Angadjivand, S. Regulation of cell-cultured meat. Congressional Research Service. 1–2 (2018).

Poinski, M. Tracking the comments on cell-based meat labeling. Food Dive (2022). Available at: https://www.fooddive.com/news/cell-based-cultivated-meat-comments-tracker-usda/623608/ (Accessed: November 2022).

Langelaan, M. L. P. et al. Meet the new meat: Tissue engineered skeletal muscle. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 21, 59–66 (2010).

Post, M. J. et al. Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nat. Food 1, 403–415 (2020).

Reis, G. G., Heidemann, M. S., Borini, F. M. & Molento, C. F. Livestock value chain in transition: Cultivated (cell-based) meat and the need for breakthrough capabilities. Technol. Soc. 62, 101286 (2020).

Bryant, C. J. & Barnett, J. C. What’s in a name? consumer perceptions of in vitro meat under different names. Appetite 137, 104–113 (2019).

Post, M. J. Cultured meat from stem cells: Challenges and prospects. Meat Sci. 92, 297–301 (2012).

Szejda, K. Cellular agriculture nomenclature: optimizing consumer acceptance. (2020).

Szejda, K., Bryant, C. J. & Urbanovich, T. US and UK consumer adoption of cultivated meat: a segmentation study. Foods 10, 1050 (2021).

Freidrich, B. Cultivated meat: a growing nomenclature consensus. The Good Food Institute. at https://gfi.org/blog/cultivated-meat-a-growing-nomenclature-consensus/ (2021).

Food Entrepreneurs. Must-see Outdoor Campaigns by Plant-Based Brands. at https://www.foodentrepreneurs.com/5-must-see-outdoor-campaigns-by-plant-based-brands/ (2022, July).

Watson, E. ‘Cell-based meat’ not the most consumer-friendly term, reveals GFI consumer research. Foodnavigator-Usa.Com at https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2018/09/30/Clean-meat-is-problematic-but-cell-based-meat-isn-t-perfect-either-reveals-GFI-consumer-research (2018, September).

Specht, E. A., Welch, D. R., Rees Clayton, E. M. & Lagally, C. D. Opportunities for applying biomedical production and manufacturing methods to the development of the Clean Meat Industry. Biochemical Eng. J. 132, 161–168 (2018).

Friedrich, B. Why GFI uses the term “cultivated meat”. at https://gfi.org/blog/cultivatedmeat/ (2019).

Ives, M. Singapore Approves a Lab-Grown Meat Product, a Global First. The New York Times. at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/02/business/singapore-lab-meat.html (2020, December).

FDA. CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=102&showFR=1#:%7E:text=(c)%20The%20common%20or%20usual,in%20the%20food%20has%20a (2020a, April).

FDA. Labeling of Foods Comprised of or Containing Cultured Seafood Cells; Request for Information. Federal Register. at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/10/07/2020-22140/labeling-of-foods-comprised-of-or-containing-cultured-seafood-cells-request-for-information (2020b, October).

Regulations.Gov. Labeling of Foods Comprised of or Containing Cultured Seafood Cells; Request for Information at https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2020-N-1720-0001/comment (2021).

USDA. USDA Seeks Comments on the Labeling of Meat and Poultry Products Derived from Animal Cells. at https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/09/02/usda-seeks-comments-labeling-meat-and-poultry-products-derived (2021, September).

Wilks, M. & Phillips, C. Attitudes to in vitro meat: a survey of potential consumers in the United States. PloS One. 12, 4–8 (2017).

Food allergies. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/food-allergies (Accessed: 3rd November 2022).

Prolific. What are the advantages and limitations of an online sample? at: https://researcher-help.prolific.co/hc/en-gb/articles/360009501473-What-are-the-advantages-and-limitations-of-an-online-sample (Accessed: 3rd November 2022).

Ibrahimi Jarchlo, A. & King, L. Survey of consumer perceptions of alternative, or novel, sources of protein. Food Standards Agency 8-9 at https://www.food.gov.uk/research/behaviour-and-perception/survey-of-consumer-perceptions-of-alternative-or-novel-sources-of-protein (2022).

Siddiqui, S. A. et al. Marketing strategies for cultured meat: a review. Appl. Sci. 12, 8795 (2022).

Aleph Farms. Aleph Farms and Mitsubishi Bring Cultivated Meat to Japan. at https://www.prnewswire.com/il/news-releases/aleph-farms-and-mitsubishi-bring-cultivated-meat-to-japan-301200863.html (2021, January).

Food Processing Technology. BRF and Aleph Farms sign MoU to introduce cultivated meat in Brazil. at https://www.foodprocessing-technology.com/news/brf-and-aleph-farms-sign-mou-to-introduce-cultivated-meat-in-brazil/ (2022, July).

Mellon, J. & Friedrich, B. Moo’s law an investor’s guide to the new agrarian revolution. (Fruitful Publications, 2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.B. designed the survey and performed the analytic calculations. M.M. led the background research and analysis of FDA and USDA data. Both authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing non-financial interests but the following competing financial interests: This research was commissioned and funded by Wildtype. The funder had no part in data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malerich, M., Bryant, C. Nomenclature of cell-cultivated meat & seafood products. npj Sci Food 6, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-022-00172-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-022-00172-0