Abstract

Chemical decontamination during processing is used in many countries to mitigate the Campylobacter load on chicken meat. Chlorine is a commonly used sanitizer in poultry processing to limit foodborne bacterial pathogens but its efficacy is limited by high bacterial loads and organic material. Acidified sodium chlorite (ASC) is a potential alternative for poultry meat sanitization but little is known about its effects on the cellular response of Campylobacter. In this study, the sensitivity of C. jejuni isolates to ASC was established. RNAseq was performed to characterize the transcriptomic response of C. jejuni following exposure to either chlorine or ASC. Following chlorine exposure, C. jejuni induced an adaptive stress response mechanism. In contrast, exposure to ASC induced higher oxidative damage and cellular death by inhibiting all vital metabolic pathways and upregulating the genes involved in DNA damage and repair. The transcriptional changes in C. jejuni in response to ASC exposure suggest its potential as an effective sanitizer for use in the chicken meat industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Campylobacter spp. are the leading bacterial cause of foodborne gastroenteritis in humans1,2. Raw and improperly handled chicken meat are two of the most commonly identified sources of Campylobacter during traceback investigations; therefore, reducing Campylobacter levels on raw poultry meat is an important aspect of food safety3. Campylobacter spp. often colonize the intestinal tract of broiler chickens and during processing, carcasses and meat pieces can become contaminated4. Globally, the prevalence of Campylobacter contaminated poultry carcasses ranges between 60 and 80%5. Improper food handling procedures and poor kitchen hygiene measures can increase the risk of cross-contamination6.

The manufacturing of poultry products is highly regulated and many regulatory agencies recommend the use of generally recognized as safe (GRAS) sanitizers to mitigate Campylobacter in the food supply chain7,8. GRAS chemicals, such as chlorine, chlorine dioxide (ClO2), sodium hypochlorite (SH), acidified sodium chlorite (ASC), peracetic acid (PAA), and ozone have been recommended for use in processing plants in countries including Australia, New Zealand9, and the USA10. The European Union does not permit the use of chlorine during processing due to health and safety issues11.

Historically, chlorine has been the most commonly used sanitizer in poultry meat processing in the USA, Australia, New Zealand, and most Asian countries12,13,14. Despite its widespread use, it is less effective than ASC, PAA, or trisodium phosphate in reducing Campylobacter levels on chicken meat12,15. At concentrations widely used in the poultry meat industry, chlorine induces sublethal injury that is significantly impacted by bacterial load and organic matter content16. Considering the limitations of chlorine, ASC has been tested by several groups as an alternative to reduce Campylobacter contamination on carcasses14,17.

Several countries in Europe, Canada, and Australia recommend the use of ASC (<1200 ppm sodium chlorite, pH 2.3–2.9) for chemical decontamination in the food industry18,19. ASC is an oxidative broad-spectrum antimicrobial, which generates chlorous acid that gradually decomposes into chloride ion, chlorate ion, chlorine, and ClO220. It has been hypothesized that uncharged chlorous acid penetrates the bacterial cell membrane and disrupts protein synthesis by reacting with sulfhydryl, sulfide, and disulfide in nucleotides21.

Factors that potentially affect the bactericidal activity of ASC, however, have not been explored. The chemical decontamination of chicken carcasses, for example, generally occurs at low temperatures (<5 °C) to prevent bacterial replication and in the presence of organic matter. In the present study, we investigated the in vitro susceptibility of Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) over a range of ASC concentrations. Transcriptional analysis of C. jejuni following exposure to chlorine and ASC was conducted to characterize the bacterial response to these chemicals.

Results

Bactericidal activity of acidified sodium chlorite on Campylobacter jejuni

All C. jejuni isolates (n = 89) exhibited higher sensitivity to ASC. For all isolates, both the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values were 7.03 ppm. Time-kill curves confirmed the sensitivity of the C. jejuni isolates. Following exposure to ASC, none of the isolates were cultured from any of the ASC concentrations tested (900–1.76 ppm) (Fig. 1a, b, c, d). No significant variation in bacterial titre was observed over time for C. jejuni isolates suspended in either nutrient broth no. 2 (NB2) (Fig. 1a, b) or 0.9% saline (Fig. 1c, d). To understand the role of pH in inactivation, C. jejuni isolates were also exposed to acidified 0.9% saline or NB2 (pH 2.5). Culturability of the C. jejuni isolates significantly (P < 0.0001) declined over time both at 5 and 25 °C. All the C. jejuni isolates declined to the minimum detection level at 25 °C in the acidified NB2 within 45 min, while all isolates were inactivated within 60 min at 5 °C. C. jejuni exhibited higher susceptibility to acidified 0.9% saline, while the culturability was completely inhibited after 30 min at both temperatures.

In time-kill assays (a, b, c, d), ATCC C. jejuni 33221 and seven chicken meat isolated C. jejuni were exposed to ASC (900, 450, 225 ppm) for 60 min. Broth control (dark orange lines), acidified broth control (light orange hash lines), 0.9% saline control (dark blue lines), and acidified 0.9% saline control (light blue hash lines) were compared with ASC treated groups (black lines). Temperature effect was compared at 5 °C (a, c) or 25 °C (b, d). In inactivation assays (e, f, g, h), the same C. jejuni isolates with ATCC strain were exposed to ASC (1.76–900 ppm) for 1 min. Inactivation kinetics were determined for both 106 CFU/mL (e, f) at 5 °C (e) and 25 °C (f) and the 108 CFU/mL (g, h) at 5 °C (g) and 25 °C (h). Data are presented as mean log10 CFU/mL ± SEM. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection of culturable bacteria. (NS; 0.9% saline, ANS; acidified 0.9% saline).

ASC exhibited a strong antimicrobial effect against all C. jejuni isolates at both 5 and 25 °C (Fig. 1e, f, g, h). After a 1-min exposure, no culturable bacteria were observed in any of the ASC concentrations tested. Bacterial load did not affect the efficacy of ASC. Aliquots of non-culturable C. jejuni were transferred to Preston broth (resuscitation media) to characterize the recovery potential following ASC exposure. None of the inactivated C. jejuni isolates at either bacterial concentration (106 or 108 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL) were resuscitated.

Transcriptome profiling of C. jejuni post-exposure to chlorine and ASC

Chlorine is a commonly used sanitizer in the chicken meat industry but unlike ASC, its efficacy is linked with bacterial load and the presence of organic materials16. Here, the transcriptional effects of both the ASC and chlorine on C. jejuni were investigated at both 5 and 25 °C. Overall gene regulation was highly dependent on the treatment group (Fig. 2). A significantly higher (P ≤ 0.01) number of regulated genes were observed at 5 °C compared with 25 °C.

A single C. jejuni isolate was exposed to ASC or chlorine at either 5 or 25 °C and the RNA obtained was processed for RNA sequencing. The number of significantly regulated bacterial genes following exposure to chlorine (black) or ASC (gray) was computed by using C. jejuni exposed to 0.9% saline as a reference control. The regulated genes were also assessed in ASC treatment group (white) using chlorine as a control.

Chlorine exposure at 5 °C resulted in the upregulation of 97 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), while 85 were downregulated. Biological pathway analysis of these genes showed that bacterial-type flagellum-dependent cell motility, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle), cellular respiration, sulfur compound metabolic process, and acid-thiol ligase activity were activated (Fig. 3a, b). Pathway analysis of the downregulated genes showed that ribosome biogenesis, transferring activity, and ncRNA processing were inhibited by chlorine exposure at 5 °C (Fig. 3c, d). At 25 °C, 12 of the most significantly upregulated genes are involved in oxidative stress and ATP synthesis (Table S1). Genes related to flagellum assembly, catalase activity, and DNA metabolic process were downregulated (Table S1).

Pathways enriched by mapping the upregulated (a, b) DEGs obtained from C. jejuni post-exposure to chlorine at 5 °C. Pathways enriched by the downregulated (c, d) DEGs obtained from C. jejuni post-exposure to chlorine at 5 °C. Only significantly (P < 0.05) enriched pathways were obtained for biological pathway analysis of the regulated DEGs (FDR < 0.05; log2 fold change >1 or <−1) in ClueGO and CluePedia plugins in Cytoscape. In the graph, the length of individual bars indicates the percent of DEGs associated with respective terms out of the total associated genes.

Following exposure to ASC at 5 °C, 13 C. jejuni genes involved in transmembrane transport biological pathway were upregulated (Fig. 4a, b). Downregulated DEGs annotated to biological pathways including the generation of precursor metabolites and energy, oxidoreductase activity, and integral component of membrane (Fig. 4c, d). Exposure to ASC at 25 °C, resulted in the significant upregulation of 47 and downregulation of 13 DEGs that could not be analyzed for biological pathway analysis in ClueGO and CluePedia. Investigation of the individual upregulated DEGs revealed that most of these genes are involved in ion binding activity (Table S2). Increased expression of electron transport genes, catalytic and iron-sulfur cluster binding genes, as well as efflux protein genes was also observed. C. jejuni responded to oxidative stress through the upregulation of Cj0198c, which induces DNA replication and DNA repair through the involvement of recR. The downregulated DEGs included genes involved in flagellar motility and biosynthesis, periplasmic, and integral membrane protein activity (Table S3).

Pathways enriched by mapping the upregulated (a, b) and downregulated (c, d) DEGs obtained from C. jejuni post-exposure to ASC at 5 °C. DEGs significantly (FDR < 0.05; log2 fold change >1 or <−1) regulated in C. jejuni in response to ASC treatment were mapped in ClueGO and CluePedia plugins in Cytoscape and only the significantly (P < 0.05) enriched biological pathways were visualized. In the graph, the length of individual bars indicates the percent of DEGs associated with respective terms out of the total associated genes.

The transcriptomic response of C. jejuni exposed to ASC vs. chlorine was compared. At 5 °C, the majority of upregulated genes were found to be involved in rRNA processing, kinase activity, and endoribonuclease activity (Fig. 5a, b). Downregulated DEGs were annotated to biological pathway terms, such as bacterial flagella dependant cell motility and acid thiol ligase activity (Fig. 5c, d). At 25 °C, exposure to ASC resulted in 59 upregulated DEGs that annotated to pathway terms, including transport, TCA cycle, and integral membrane components (Fig. 6a, b). Downregulated DEGs (n = 10) play a role in flagellar motility and biosynthesis (Table S4).

Pathways enriched by mapping the upregulated (a, b) and downregulated (c, d) DEGs at 5 °C. DEGs significantly (FDR < 0.05; log2 fold change >1 or <−1) regulated in C. jejuni were mapped in ClueGO and CluePedia plugins in Cytoscape and only significantly (P < 0.05) enriched biological pathways were visualized. In the graph, the length of individual bars indicates the percent of DEGs associated with respective terms out of the total associated genes.

Pathways enriched by mapping upregulated (a, b) DEGs obtained from C. jejuni post-exposure to ASC at 25 °C. DEGs significantly (FDR < 0.05; log2 fold change >1 or <−1) upregulated in C. jejuni were mapped in ClueGO and CluePedia plugins in Cytoscape and only significantly (P < 0.05) enriched biological pathways were visualized. In the graph, the length of individual bars indicates the percent of DEGs associated with respective terms out of the total associated genes.

To rule out temperature as a confounding factor, transcriptome data obtained from bacteria suspended in 0.9% saline at 5 and 25 °C were compared; a nonsignificant effect of temperature was observed.

Transcriptomic data were validated using qPCR. Primers used for RNAseq data validation showed high target specificity. The amplification efficiency of individual primers was in a range of 95–102% (Table S5). Regression analysis of the qPCR vs. the RNA-sequencing data showed a positive correlation (P < 0.0001; R2 = 0.878) (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Campylobacter contamination of chicken meat remains a significant public health issue and its control is critical for the global poultry industry. ASC has previously been shown to be highly effective at reducing Campylobacter loads on chicken carcasses17,22 but little is known about its effects on bacterial physiology, cellular, and molecular responses. In this study, all Campylobacter jejuni isolates were inhibited at 7.03 ppm ASC demonstrating the effectiveness of this sanitizer at a far lower concentration than the recommended range of 500–1200 ppm23. These results were supported by time-kill and inactivation experiments, which showed that irrespective of exposure time and concentration, the culturability of the C. jejuni isolates was completely inhibited by low concentrations of ASC. Our results are in agreement with a previous investigation where foodborne pathogens exposed to 10 ppm of ASC were not resuscitated24. A similar kinetic has also been observed for the inactivation of Salmonella Typhimurium following exposure to 10 ppm ASC at pH 2.524.

In this study, the high susceptibility of C. jejuni confirms the antimicrobial properties of ASC. Although the inactivation efficacy of chlorine is highly dependent on bacterial load16, our present findings with ASC revealed no effect of bacterial load. This could be due to the higher oxidizing capacity of the intermediate chemicals, ClO2 and chlorous acid, which are produced in ASC, compared with the hypochlorous acid produced in chlorine25. The presence of organic material (NB2 broth) also did not have an effect on bacterial culturability confirming the efficacy of ASC. To confirm these findings, field experiments are required, as the effectiveness of ASC in a commercial processing environment may vary due to the presence of organic matter and variable bacterial load.

The cellular response of C. jejuni after exposure to chlorine or ASC was further explored using transcriptomic analysis. Following exposure to either chlorine or ASC, more genes were significantly upregulated at 5 °C than 25 °C. The downregulation of genes was also higher at 5 °C than at 25 °C for all the treatment groups. This is likely due to the suppression of cellular activities in response to both the chemical and temperature stress.

Exposure of C. jejuni to chlorine induced several biological pathways including genes involved in bacterial-type flagellum-dependent cell motility and membrane proteins. Chlorine exposure has been shown to induce changes in membrane permeability and the morphology in C. jejuni16. Furthermore, oxidative phosphorylation in the cell membrane following chlorine exposure also leads to leakage of RNA, nucleotides, and proteins26 and increases energy requirements to compensate for the loss of intracellular components. Consistent with this, in the present study, C. jejuni genes involved in both the TCA cycle and cellular respiration pathways were upregulated after exposure to chlorine. C. jejuni also responded to oxidative stress by significantly upregulating genes involved in oxidoreductase activity including sodB, oorAB, hydBC, and dsbD. Pathway analysis of downregulated genes revealed that genes involved in ribosome biogenesis and ncRNA processing were downregulated by chlorine exposure at 5 °C suggesting that bacteria were exhibiting reduced cell growth, division, and replication caused by both temperature and chlorine induced stress. Similar responses have been shown in Saccharomyces cerevisiae after exposure to an alkylating agent, methyl methanesulfonate27. Although the DEGs were not expressed significantly at 25 °C compared to 5 °C, the cellular response of C. jejuni to chlorine caused by alteration of the membrane permeability was significant due to the upregulation of the genes encoding proteins involved in electron transport and iron-sulfur cluster binding (Cj1713, fdxB).

The response of C. jejuni to ASC was also assessed at 5 and 25 °C. Following exposure to ASC at 5 °C, C. jejuni upregulated DEGs involved in the activation of transmembrane transport biological pathways suggesting changes in bacterial membrane integrity and permeability28,29. Interestingly, the vital metabolic pathways in C. jejuni were suppressed. Genes encoding proteins involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy and cellular respiration (fdhC and nrfA) and oxidoreductase activity (fdhABC) were downregulated. This indicates a loss of cellular functions and survivability for C. jejuni after exposure to ASC.

The DEGs upregulated at 25 °C included proteins involved in reducing intracellular iron and the prevention of secondary oxidative DNA damage. In Escherichia coli, increased iron is important for the recovery of cells from stress30. Although Campylobacter lacks an SOS response in programmed cellular death31, in the current study, the upregulation of genes involved in DNA damage and repair (recR and Cj0198c) and efflux protein (Cj1174) indicated the cellular response mechanism in bacterial cell death. Activation of genes involved in DNA damage and repair has been noted in other bacteria treated with SH and hydrogen peroxide and PAA28,32.

To understand the effects of ASC at 5 and 25 °C, the data were analyzed using the chlorine exposure treatment as a control. The downregulation of DEGs involved in cellular metabolism and flagella-dependent cell motility at 5 °C indicated that oxidative injury was greater following the exposure to ASC. The upregulation of genes encoding proteins involved in rRNA processing and endoribonuclease activity indicated the ROS damaged DNA and RNA by ASC. Interestingly, genes encoding proteins involved in ROS induced bacterial survivability against the oxidative stress, sodB were not upregulated in the conditions applied in the current study. Downregulation of katA indicates that C. jejuni was not able to survive under oxidative stress induced by exposure to ASC at 5 °C. A similar response has been shown in SOS-induced cellular death in Escherichia coli following exposure to UV radiation33. Data from the 25 °C treatment group showed that C. jejuni was responding to the oxidative stress and the cellular damage was not as significant as recorded at 5 °C. The upregulation of genes involved in TCA cycle and membrane functions (putP, dcuB, lctB, and febB) indicated the oxidative response caused by membrane integrity changes. C. jejuni exhibited a similar stress response following exposure to ajoene34. Downregulated genes were mainly involved in flagellar motility and biosynthesis indicated the suppressed flagella activity by downregulation of cell membrane and chemotaxis activity. Our results indicated that oxidative cellular damage to C. jejuni was greater after exposure to ASC compared to chlorine and this was further enhanced at 5 °C.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the sensitivity of Campylobacter jejuni to ASC. In ASC, C. jejuni experienced severe, irreversible injury that ultimately resulted in bacterial cell death and lysis. ASC induced lethal oxidative injury in C. jejuni by inhibiting all vital cellular functions that were further aggravated at low temperatures. In contrast, chlorine induced an adaptive stress response mechanism enabling C. jejuni to survive oxidative stress. The transcriptomic data presented here represent gene expression of the surviving cell population, which could include a range of states of bacterial cell death and survival. Outcomes of these experiments have significant implications for food safety and public health. Further studies, however, are necessary to investigate the stress response mechanisms in C. jejuni enabling them to survive chemical stress in the food chain, and how this affects bacterial virulence. Additional investigation is also required to identify optimal points in poultry meat processing to utilize ASC for the control of Campylobacter spp.

Methods

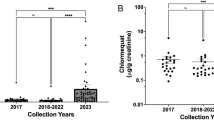

Campylobacter isolates

Campylobacter jejuni (n = 89) isolates previously cultured from broiler carcasses17 were selected for this study. Species identification was confirmed previously16. Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 33291 was included as a control strain. Pure cultures were maintained long-term at −80 °C in a 50:50 mixture of brain heart infusion broth and 100% glycerol. Isolates were resuscitated on sheep blood agar (SBA) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Australia) and incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for 48 h.

MIC and MBC of acidified sodium chlorite

The MIC of ASC was determined using the broth micro-dilution method in NB2 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Australia) according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute guidelines35. C. jejuni ATCC 33291 was included as an experimental control. NB2 was acidified to pH 2.5 using 4 M citric acid (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Dilutions of ASC (3600–7.03 ppm) were prepared using 31% sodium chlorite (ChemSupply, Australia) in acidified NB2. Campylobacter inoculums were prepared using a 0.5 McFarland standard and confirmed by measuring the optical density at 600 nm to obtain 108 CFU/mL. To determine MIC, 10 μL of the bacterial culture was inoculated into 990 μL of ASC in 96-well round-bottom micro-titre plates. NB2 without ASC and containing Campylobacter was a positive control and NB2 only was the negative control. MIC plates were incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for 20 h. The lowest concentration that did not give visible Campylobacter growth was defined as the MIC. Isolates were tested in duplicate and the assay was repeated twice.

Ten μL of broth from each well-showing growth inhibition was drop plated onto SBA plates and incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for 20 h to determine the MBC. The MBC was defined as the lowest bactericidal concentration of ASC required to kill Campylobacter.

Time-kill assay

Time-kill experiments were performed to characterize C. jejuni susceptibility to three concentrations (225, 450, and 900 ppm) of ASC in the presence of organic materials. Seven C. jejuni isolates were randomly selected for these experiments. NB2 or 0.9% saline was acidified with 4 M citric acid to pH 2.5 before the addition of ASC. The bacterial inoculum was prepared in 0.9% saline as described above. Overall, 10 μL of inoculum was added into 990 μL of each ASC dilution to obtain 106 CFU/mL. Experiments were conducted at both 5 and 25 °C. Bacterial counts were determined at multiple time points post exposure (1, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60 min). Serial tenfold dilutions in 0.9% saline were prepared and 10 μL of each dilution was drop plated onto SBA and incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2. Colonies were enumerated and reported as CFUs/mL. Each treatment group contained three biological replicates and the experiments were repeated twice.

Inactivation of C. jejuni in ASC

Inactivation assays and time-kill experiments were conducted to further characterize the sensitivity of C. jejuni isolates to ASC. ASC concentrations ranging from 900 to 1.76 ppm were prepared in acidified 0.9% saline (pH 2.5). To determine the effect of Campylobacter load, two inoculum doses, 106 and 108 CFU/mL were exposed to ASC for 1 min at either 5 or 25 °C. The bacterial count was obtained by drop plating 10 μL of serial tenfold dilutions onto SBA plates and incubating at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for 48 h. Inactivation experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated twice. Following exposure, 100 μL of each treatment and control groups were inoculated into 900 μL Preston broth (NB2 with Campylobacter selective supplement) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Australia) and incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for resuscitation. After 24 and 48 h of incubation, 10 μL from each treatment group was drop plated onto SBA and incubated at 42 °C in 10% CO2 for 48 h. The resuscitation experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

Campylobacter jejuni RNA extraction for RNA sequencing and qPCR

To study the transcriptional regulation of Campylobacter in response to chlorine and ASC exposure, a single C. jejuni isolate was incubated in NB2 at 42 °C with 10% CO2 for 48 h with agitation at 80 rpm. The broth culture was centrifuged at 4300 × g for 20 min. Pellets were resuspended in 0.9% saline to obtain 109 CFU/mL Campylobacter. Chlorine (8 ppm), ASC (900 ppm), and 0.9% saline solutions were prepared as described earlier. C. jejuni was exposed to chlorine and ASC for 2 and 1 min, respectively at 5 or 25 °C. These times reflect exposure times that are used in the poultry meat industry. In the control group, C. jejuni was exposed to 0.9% saline for 2 min. Three biological replicates were included in each treatment. After exposure, samples were centrifuged at 4300 × g for 8 min to pellet C. jejuni.

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, USA). Bacterial pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer composed of 30 μL lysozyme (100 mg/mL) (Merk, Australia), 50 μL proteinase K (20 mg/mL) (Qiagen, Australia), 2.5 μL β-mercaptoethanol (Merk, Australia), 5 μL of 10% SDS (Invitrogen, USA), and 112.5 μL of 1 M Tris EDTA buffer (Merk, Australia). Samples were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C and 20 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (Thermo Scientific, Australia) was added followed by 750 μL Trizol. The samples were mixed and incubated on ice for 5 min. To separate the RNA containing phase from phenol, 250 μL chloroform (Merk, Australia) was added. The samples were mixed, and incubated on ice for 3 min and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The top 300–350 μL of the aqueous layer was transferred into RNAse free centrifuge tubes. To precipitate RNA, 500 μL of chilled 2-propanol was added and the samples were incubated at −20 °C for 1 h. RNA pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Pellets were washed twice with 75% ethanol and allowed to dry on ice for 20 min before resuspension in 20 μL RNAse free water and were then processed for DNAse digestion (RNase Free DNase Set; Qiagen, Australia) and RNA cleanup (Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit; New England Biolab, USA) as per the manufacturers’ protocols. RNA quality and integrity were assessed using an Agilent RNA ScreenTape System in TapeStation 2200 (Agilent Technologies, Germany). RNA sequencing was performed by the Australian Genome Research Facility, Melbourne, Victoria. RNA sequencing and analysis were performed as described previously36 with modifications.

cDNA synthesis and library preparation

For cDNA library preparation, mRNA was fragmented into small pieces using heat and divalent cations with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library prep kit. First-strand cDNA was prepared using Super Script II Reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Australia) and a master mix containing dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dUTP was used in the second strand cDNA preparation as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Libraries were prepared by 3′-adenylation of cDNA fragments and amplification of the library by PCR. Libraries were pooled and clustered through the Illumina cBot system using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3 reagents followed by sequencing of 100 bp single read on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system with TruSeq SBS Kit v3 reagents. The primary sequence data were generated using the Illumina bcl2fastq 2.20.0.422 pipeline using the standard FASTQ format.

Reads mapping and transcriptome assembly

Cleaned sequence reads were aligned against the reference genome of Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 700819 (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) RefSeq GCF_000009085.1) using the STAR aligner v2.5.3a37. The feature summary table was created providing an overall mapping rate with the genome end and genome features (feature = exons). The counts of reads mapping to each known gene were summarized at the gene level using featureCounts v1.5.338. Digital gene expression values or raw gene counts were used in edgeR V3.26.539 of R packages v3.6.0 for computing differential gene expression in counts per million (CPM). Transcripts were assembled with the StringTie tool v1.3.340. Reads alignments and reference annotation-based transcript assembly (RABT) option generated assembly for known and potentially novel transcripts41.

Differential gene expression analysis

CPM values were used in edgeR to compute the DEGs in C. jejuni exposed to sanitizers at 5 and 25 °C. During the analysis, the default trimmed mean of M values normalization method of edgeR was used to normalize the counts between the treatment groups. For assessing the regulation of genes of C. jejuni affected by chlorine and ASC, the control group was used a reference at 5 and 25 °C, General Linear Model was used to quantify the DEGs.

Functional annotation of significantly regulated DEGs

The DEGs with log2 fold change ≥1 or ≤−1 and false discovery rate ≤0.05 were considered to be significantly regulated and were analyzed for functional annotation in ClueGO v2.5.642. and CluPedia43 plugins in Cytoscape v3.7.2. The DEGs were enriched for terms specific to Campylobacter jejuni: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function pathways. In ClueGO, significantly enriched biological pathways were identified by the two-sided hypergeometric test with P < 0.05 based on Benjamini–Hochberg.

RNA-Sequencing data validation by qPCR

Primers for candidate target and reference genes were designed using the NCBI software (Table S5). Ten genes that were significantly up or downregulated following the exposure to chlorine or ASC were selected. 16S rRNA, glyA, and bioD were selected as reference genes due to their stable expression under different treatment conditions. Primers were optimized for target specificity using qPCR, melt curve analysis, and products were visualized by gel electrophoresis with 2% agarose gel. For determining the amplification efficiency of individual primers, qPCR was performed on eight different fivefold serial dilutions of C. jejuni cDNA.

From individual RNA samples (n = 18), ~100 ng was reversely transcribed to cDNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Australia) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. For qPCR, using SensiFast Sybr Hi-Rox Kit (Bioline, Australia), mastermix was prepared and loaded into 384 well plates by epMotion 5075 Eppendorf robot (Eppendorf, USA). Quantitative PCR was conducted in duplicate using a 20 µL reaction volume. Thermocycling conditions in QuantStudio 6 (ABI, Australia) thermal cycler were: polymerase activation at 95 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing either at 58 or 60 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. A melting curve step was included to assess the specificity of amplification. For relative expression data analysis, the expression levels of the candidate target genes were normalized against the average of the reference genes 16S rRNA, glyA, and bioD.

Statistical analysis

Campylobacter count data were analyzed in GraphPad Prism Version 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA) using one- and two-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The relative expression data of individual genes were analyzed by 2−ΔΔCq method from quantitation cycle (Cq) values using the reference genes 16S rRNA, glyA, and bioD. qPCR data were expressed as log2 fold change.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNA sequence raw data (fastq files) have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA672226.

References

Havelaar, A. H. et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of controlling Campylobacter on broiler chicken meat. Risk Anal. 27, 831–844 (2007).

Kirk, M., Ford, L., Glass, K. & Hall, G. Foodborne illness, Australia, circa 2000 and circa 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1857 (2014).

Berrang, M. E. et al. Prevalence and numbers of Campylobacter on broiler carcasses collected at rehang and postchill in 20 US processing plants. J. Food Prot. 70, 1556–1560 (2007).

FSANZ. Scientific Assessment of the Public Health and Safety of Poultry Meat in Australia. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/documents/poultry/. 1–233 (2006).

EFSA. Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ), scientific opinion on quantification of the risk posed by broiler meat to human campylobacteriosis in the EU. EFSA J. 8, 89 (2010).

Donelan, A. K., Chambers, D. H., Chambers IV, E., Godwin, S. L. & Cates, S. C. Consumer poultry handling behavior in the grocery store and in-home storage. J. Food Prot. 79, 582–588 (2016).

McKee, S. R. Salmonella and Campylobacter control during poultry processing. In International Poultry Scientific Forum. Vol 24 (Atlanta, Georgia, 2011).

Moore, J. E. et al. Campylobacter. Vet. Res. 36, 351–382 (2005).

FSANZ. Primary production & processing standard for poultry meat. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code - Standard 4.2.2. 1–10 (2005).

USDA. US Department of Agriculture. Pathogen Reduction; Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Systems. 60 FR 54450. FSIS final rule. US Government Printing Office. 54450–54457 (1995).

EFSA. Scientific opinion on the public health hazards to be covered by inspection of meat (poultry), Appendix B. EFSA J. 10, 2741 (2012).

Bauermeister, L. J., Bowers, J. W., Townsend, J. C. & McKee, S. R. Validating the efficacy of peracetic acid mixture as an antimicrobial in poultry chillers. J. Food Prot. 71, 1119–1122 (2008).

Jacobs-Reitsma, W. Campylobacter in the food supply. Campylobacter, 2nd edn (eds Nachamkin, I. & Blaser, M.) 467–481 (2000).

Sexton, M. et al. Effect of acidified sodium chlorite treatment on chicken carcases processed in South Australia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 115, 252–255 (2007).

Bashor, M. P. et al. Effects of carcass washers on Campylobacter contamination in large broiler processing plants. Poult. Sci. 83, 1232–1239 (2004).

Muhandiramlage, G. K., McWhorter, A. R. & Chousalkar, K. K. Chlorine induces physiological and morphological changes on chicken meat Campylobacter isolates. Front. Microbiol. 11, 503 (2020).

Chousalkar, K., Sims, S., McWhorter, A., Khan, S. & Sexton, M. The effect of sanitizers on microbial levels of chicken meat collected from commercial processing plants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16, 4807 (2019).

FDA. Food and drug administration. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21. Food and drugs. Revised as of April 1, 2020. 21CFR173.325. 3 (2020).

FSANZ. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code, Standard 1.3.3 – processing aids. http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/code/. 1–4 (2013).

Krogulec, T. Stabilised Chlorine Dioxide Solution. Patent Application Publication. US 2012/0225135 A1United States. 1–32 (2012).

Warf, C. & Kemp, G. The chemistry and mode of action of acidified sodium chlorite. IFT annual meeting. ADS Newslett. 3, 1–19 (2001).

Oyarzabal, O. A., Hawk, C., Bilgili, S. F., Warf, C. C. & Kemp, G. K. Effects of postchill application of acidified sodium chlorite to control Campylobacter spp. and Escherichia coli on commercial broiler carcasses. J. Food Prot. 67, 2288–2291 (2004).

Anonymous. Acidified sodium chlorite solutions. Secondary Direct Food Additives Permitted In Food For Human Consumption. Code of Federal Regulations – 21 CFR 173.325. (2000).

Kim, N., Park, T. & Rhee, M.-S. Enhanced bactericidal action of acidified sodium chlorite caused by the saturation of reactants. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 1447–1457 (2014).

Inatsu, Y., BARI, L., Kawasaki, S., Isshiki, K. & Kawamoto, S. Efficacy of acidified sodium chlorite treatments in reducing Escherichia coli O157: H7 on Chinese cabbage. J. Food Prot. 68, 251–255 (2005).

Venkobachar, C., Iyengar, L. & Rao, A. P. Mechanism of disinfection: effect of chlorine on cell membrane functions. Water Res. 11, 727–729 (1977).

Jelinsky, S. A. & Samson, L. D. Global response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to an alkylating agent. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 96, 1486–1491 (1999).

Ceragioli, M. et al. Comparative transcriptomic and phenotypic analysis of the responses of bacillus cereus to various disinfectant treatments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3352–3360 (2010).

Small, D. A., Chang, W., Toghrol, F. & Bentley, W. E. Toxicogenomic analysis of sodium hypochlorite antimicrobial mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74, 176–185 (2007).

Touati, D., Jacques, M., Tardat, B., Bouchard, L. & Despied, S. Lethal oxidative damage and mutagenesis are generated by iron in delta fur mutants of Escherichia coli: protective role of superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2305–2314 (1995).

Asakura, Y. & Kobayashi, I. From damaged genome to cell surface: transcriptome changes during bacterial cell death triggered by loss of a restriction–modification gene complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 3021–3031 (2009).

Palma, M., DeLuca, D., Worgall, S. & Quadri, L. E. N. Transcriptome analysis of the response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to hydrogen Peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 186, 248–252 (2004).

Courcelle, J., Khodursky, A., Peter, B., Brown, P. O. & Hanawalt, P. C. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158, 41–64 (2001).

Xue, R. et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing analysis of the synergistic antimicrobial effect of metal oxide nanoparticles and ajoene on Campylobacter jejuni. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2074 (2018).

Weinstein, M. P. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. National Comm. for Clin. Lab. Stand. 38, 1–13 (2018).

Khan, S. & Chousalkar, K. K. Transcriptome profiling analysis of caeca in chicks challenged with Salmonella Typhimurium reveals differential expression of genes involved in host mucosal immune response. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 9327–9342 (2020).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. The R package Rsubread is easier, faster, cheaper and better for alignment and quantification of RNA sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 47 (2019).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–295 (2015).

Roberts, A., Pimentel, H., Trapnell, C. & Pachter, L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 27, 2325–2329 (2011).

Bindea, G. et al. ClueGO: a cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 25, 1091–1093 (2009).

Bindea, G., Galon, J. & Mlecnik, B. CluePedia cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics 29, 661–663 (2013).

Acknowledgements

G.W. is a recipient of an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship from The University of Adelaide, Australia. Funding for this study was provided by the School of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, The University of Adelaide. Additional funding was also provided by AgriFutures, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.W., A.M., S.K., and K.K.C. conceived the project. G.W. and A.M. performed bactericidal and time-kill experiments. G.W. and S.K. optimized RNA extraction and performed the gene expression work. G.W. analyzed all the data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. K.K.C., S.K., and A.M. provided comments on all drafts of the manuscript. K.K.C. obtained funding for the work and provided access to necessary software. K.K.C. and A.M. supervised the project. All the authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weerasooriya, G., McWhorter, A.R., Khan, S. et al. Transcriptomic response of Campylobacter jejuni following exposure to acidified sodium chlorite. npj Sci Food 5, 23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-021-00103-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-021-00103-5