Abstract

This study aimed to analyze treatment guidelines of 12 SEE countries to identify non-pharmacological interventions recommended for schizophrenia, explore the evidence base supporting recommendations, and assess the implementation of recommended interventions. Desk and content analysis were employed to analyze the guidelines. Experts were surveyed across the 12 countries to assess availability of non-pharmacological treatments in leading mental health institutions, staff training, and inclusion in the official service price list. Most SEE countries have published treatment guidelines for schizophrenia focused on pharmacotherapy. Nine countries—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia—included non-pharmacological interventions. The remaining three countries—Kosovo (UN Resolution), Romania, and Slovenia—have not published such treatment guidelines, however they are on offer in leading institutions. The median number of recommended interventions was seven (range 5–11). Family therapy and psychoeducation were recommended in most treatment guidelines. The majority of recommended interventions have a negative or mixed randomized controlled trial evidence base. A small proportion of leading mental health institutions includes these interventions in their official service price list. The interventions recommended in the treatment guidelines seem to be rarely implemented within mental health services in the SEE countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Southeast European (SEE) countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Kosovo (UN Resolution), Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia) share similar socioeconomic and political backgrounds. In the last three decades, these countries have gone through rapid socio-economic changes that have inevitably profoundly impacted both the populations’ mental health and development of mental health services1,2.

In these countries, attempts have been made to reform mental health care, improve patients’ human rights, and transition from asylum-based care to community-based care3. However, a recent evaluation of mental health care services in Central Europe and Eastern Europe suggests that mental health care across the region remains based around treatment in psychiatric hospitals with prescription medications2. This approach is particularly problematic for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia because it leads to further social exclusion and inequality of this vulnerable group.

Schizophrenia is a severe and chronic illness with complex symptomatology, which affects up to 1% of the general population4. The symptoms can vary but often include hallucinations, delusions, disordered thinking, social withdrawal, alogia, and abulia5. Current treatment guidelines for schizophrenia published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK and the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team in the USA suggest a combined-therapy approach including pharmacological (e.g. antipsychotics) and non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., talking therapy and family support)6,7.

Non-pharmacological interventions aim to improve the individual potential of people with mental disorders in their day-to-day life activities, including social and work domains8. They might have an important role in reducing the risk of relapse in schizophrenia9. In particular, psychosocial interventions (PIs) can be divided into three categories: (1) those based on education and support, (2) those including life and social skills training, and (3) problem-focused or symptom-focused interventions10. Another important group of interventions are psychotherapies (PTs) which can be defined as interpersonal interventions delivered by a trained clinician, and individualized to the client’s problem or modified so they can be suitable for delivery to a couple, family, or another group of clients11. PTs include two broad categories: system and individual interventions. It is important to note that a sharp boundary between PIs and PTs cannot be drawn. Most commonly recommended evidence-based non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive remediation, psychoeducation, social and coping skills, family interventions, and assertive community treatment (ACT) or case management12. Studies including non-pharmacological interventions as part of the multi-modal approach report mixed findings regarding their effectiveness13 as well as inconsistent implementation14.

Although a combined-therapy approach has been recommended in other regions, the topic of non-pharmacological treatment for individuals with schizophrenia standalone or as part of holistic approach to schizophrenia has received little research interest in SEE. We focused on non-pharmacological treatment in this study in order to bridge the gap in knowledge about its availability and implementation in SEE.

Aims of the study

This study aimed to analyze treatment guidelines of 12 Southeast European countries to identify which non-pharmacological interventions are recommended for treating schizophrenia and if recommended interventions are based on robust evidence. The study also aims to explore the implementation of recommended interventions in each country.

Results

Treatment guidelines

The majority of participating countries (N = 9, 75%) have published treatment guidelines for schizophrenia. These documents were available and published under the following terms that can be used interchangeably: national guidelines, treatment guidelines, clinical instructions, therapeutic guidelines, practice guidelines, national clinical protocol, and instructions for treatment of schizophrenia. They included recommendations for both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment for schizophrenia. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, two treatment guidelines were identified, both covering pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. In Slovenia treatment guidelines for schizophrenia included only pharmacological treatment15. Finally, Kosovo (UN Resolution) and Romania do not have treatment guidelines for schizophrenia. Hence, 9 documents were analyzed in total. Table 1 shows recommended non-pharmacological interventions and indicators of implementation in each country.

Six out of 10 analyzed documents were published by the Ministry of Health of the respective country. The remaining four documents were published either by relevant professional organizations or by clinicians as follows. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Manual for psychosocial interventions for persons with schizophrenia (2012) was published by “Dr Mustafa Šehović Public Medical Center” and the Association for Mutual Support and Mental Distress (FENIX)16. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia was initially published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and was subsequently translated into Bulgarian and adopted by mental health policymakers in Bulgaria17. In Croatia, Guidelines for psychosocial procedures and psychotherapy (2017) was published by the Croatian Medical Association, Croatian Psychiatric Association, and Association for Mental Health Promotion (“Svitanje”)18. Finally, although not an official guideline, a widely accepted document containing recommendations and examples of good clinical practice in treating schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Romania is a monograph written by three Romanian clinicians with extensive experience in the treatment of psychotic disorders19.

The publishing year span was 20 years, starting with Bulgaria’s national guidelines published in 1998 and ending with the Albanian national guidelines published in 2018. On average, these documents were published 8.7 years ago (median value is 7 years).

As shown in Table 1, the number of recommended non-pharmacological interventions varied across countries and analyzed documents from 4 in North Macedonia to 11 in Bulgaria and Croatia. The average number of recommended interventions was 7. The 10 most recommended interventions in national guidelines were the following: CBT and family therapy/interventions (9 recommendations each), psychoeducation and social skills training (8 recommendations each), professional rehabilitation/supported employment (7 recommendations), and art therapy (6 recommendations). Supportive therapy and counseling, psychoanalytic/psychodynamic therapy, cognitive remediation/rehabilitation, occupational/ergotherapy were recommended in 3 out of 10 analyzed documents.

Context of delivery and identified benefits of recommended interventions

Treatment guidelines were analyzed for additional information regarding the contextual and procedural recommendations of delivering non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia, along with empirical underpinning of their effectiveness.

Albania—Diagnostic and therapeutic care protocol for schizophrenia (Ministry of Health, 2018) contains very scarce information regarding non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia20. These therapeutic modalities are only listed as treatment programs that can be added to standard care offered to individuals with schizophrenia. The document does not contain definitions of interventions or their specific purpose.

Bosnia and Herzegovina—National guide for treating schizophrenia (Ministry of Health of the Canton of Sarajevo; Institute for Scientific Research and Development of University Clinical Center Sarajevo, 2006) does not discuss definitions and premises of specific interventions, but rather focuses on their aims and benefits21. Manual for psychosocial interventions for persons with schizophrenia contains a general introductory section about non-pharmacological interventions, their use, and usefulness in treating schizophrenia16. Furthermore, the document offers detailed descriptions of specific psychosocial interventions in the scope of psychoeducation.

Croatia—Psychiatric disorders encompassing psychosis and schizophrenia: Guidelines for psychosocial procedures and psychotherapy (Croatian Medical Association, Croatian Psychiatric Association, & Association for Mental Health Promotion, 2017) provides an overall description of various interventions as well as recommendations on when to use each of them18.

Greece—Instructions for treating schizophrenia in Greece (Ministry of Health, 2015) offers a detailed overview of various non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia. It contains information on when, where, and how it is best to deliver different interventions22.

Moldova—Schizophrenia first episode psychotic: National clinical protocol (Ministry of Health, 2016) contains several tables with recommendations on specific effects and how to deliver different non-pharmacological interventions, with no indications whether the recommendations are evidence-based23.

Montenegro—National guidelines of good clinical practice in treating schizophrenia (Ministry of Health, 2013) provides short descriptions of non-pharmacological interventions and the strength of evidence for their effectiveness based on the results of studies conducted in international settings24.

North Macedonia—Instructions for practicing evidence-based medicine within the treatment of schizophrenia (Ministry of Health, 2013) includes a list with several non-pharmacological interventions. Information provided is very scarce. This guideline refers to the degree to which each recommended intervention is supported by research evidence25.

Serbia—National guidelines of good clinical practice in treating schizophrenia (Ministry of Health Working Group 2013) were gathered to create and implement good clinical practice guidelines. The benefits of the recommended interventions were listed and supported by scientific references. Furthermore, the context of their delivery was explained26.

Table 2 shows Kosovo (UN Resolution) and Romania, two countries without published treatment guidelines. Slovenia has published treatment guidelines for schizophrenia however they do not recommend non-pharmacological interventions15. However, a handbook Where and how to get help for mental illness? provides a list of the recommended interventions coupled with their positive effects on mental health27. In Romania, a handbook of Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (2012) was written by Ienciu, Romosan, and Lazarescu19. The handbook cites various scientific sources when highlighting the importance of psychosocial rehabilitation techniques and methods in schizophrenia. It offers an overview of several interventions with detailed descriptions of their principles and usefulness.

Evidence base for recommended non-pharmacological interventions

Table 3 includes short descriptions of each recommended intervention from the analyzed treatment guidelines, country of origin, availability of treatment manual, duration of staff training, RCT evidence base, and evidence derived from SEE countries.

In total, 19 non-pharmacological interventions for individuals with schizophrenia were assessed. The majority of interventions were originally developed in the USA (n = 11) and manualized (n = 13). Seven interventions have a negative RCT evidence base meaning that, when compared to standard treatment/active control, the interventions were not effective. These interventions were: art therapy, compliance therapy (although adherence therapy, which was listed in the expert survey within the same item [adherence/compliance therapy] appeared to be effective), psychodynamic/ psychoanalytical therapy, psychosocial interventions for maintaining optimal body weight, psychosocial interventions dealing with addiction problems as comorbid disorders, psychosocial interventions focused on social inclusion, and supportive therapy. Two interventions—professional (vocational) rehabilitation and psychomotor (body) therapy—have never been studied in RCTs with individuals with schizophrenia.

The remaining 10 interventions have a mixed RCT evidence base. Family interventions, psychoeducation, social skills training, and cognitive behavioral therapy have stronger evidence-base compared to other interventions.

Only two effectiveness and/or implementation studies were conducted in SEE countries. First, an RCT exploring the effectiveness of cognitive remediation group therapy in patients with schizophrenia was conducted in Greece28. The findings indicated improvements in working memory and social perception during therapy and at 3-month follow-up. Second, a case-controlled study of 50 patients enrolled in a social rehabilitation program for 6 months compared with 50 patients on the waitlist reported improved social functioning, self-esteem, and quality of life29.

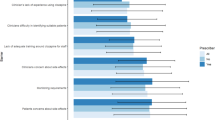

Implementation of recommended interventions

As shown in Table 1, implementation indicators varied substantially across participating institutions. Most institutions did not offer all recommended interventions and even fewer interventions were included in the official service price lists. Some interventions that were on the price lists were not offered in services, possibly due to lack of trained staff to deliver these interventions. Most institutions included in the study faced a lack of clinical staff trained to deliver recommended interventions (Table 1). In Albania, none out of seven recommended interventions were available to patients in this country’s leading psychiatric institution. In other countries, the percentage of recommended interventions that were available and staff trained to deliver these interventions ranged from 14% in Montenegro to 78% in Bulgaria. In Albania and Bulgaria, recommended non-pharmacological interventions were not included in the official service price lists. The percentage of recommended interventions that were included in the official price list ranged from 14% in Montenegro to 67% in North Macedonia.

Treatment guidelines for non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia do not exist in Kosovo (UN Resolution), Romania, and Slovenia. Expert survey data showed that some were implemented in these countries (Table 2). In Kosovo (UN Resolution), the four following interventions were available to patients, although not included in their official service price list: family therapy, psychoeducation, social skills training, and supportive therapy. Seven different interventions were implemented in Romania: art therapy, case management, CBT, ergotherapy, family therapy, psychoeducation, supportive therapy. However, none of them are on the price list of the leading institution. Finally, in Slovenia, 17 different interventions were delivered to individuals with schizophrenia. All of them have been included in the price list of the respective institution.

Discussion

This is the only study to date that explored treatment guidelines for individuals with schizophrenia in 12 SEE countries. The study looked specifically into non-pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia, which remains under researched topic globally.

The study showed that across the 12 SEE countries, 10 have published treatment guidelines for schizophrenia and 9 countries have guidelines for non-pharmacological interventions. Despite not having treatment guidelines in three countries, a range of non-pharmacological interventions were potentially available to patients with schizophrenia. Two interventions (family therapy and psychoeducation) were recommended by most treatment guidelines. The majority of recommended interventions had a mixed or negative RCT evidence base which is almost exclusively comprised of studies conducted outside SEE countries. The recommended interventions were insufficiently implemented in services and only a small proportion of leading institutions included them in their official service price list.

Treatment guidelines are essential for standardizing treatment and making it more consistent and efficient for people with specific conditions30,31. Guidelines should ideally be available online and local clinicians should be able to locate them easily. In our study, the majority of participating SEE countries had published treatment guidelines for schizophrenia, which seems to be an important step in improving the quality of provided treatment. Most guidelines included descriptions of non-pharmacological interventions, aims, benefits, and instructions for delivery which could be useful for busy clinicians aiming to integrate an evolving evidence-base into practice. However, most guidelines were more than five years old and therefore included recommendations that may be outdated. For example, at the publication of existing guidelines in 2015, the evidence for art therapy was considered to be strong, but new studies have since emerged contradicting this evidence. In discussion with national experts involved in the study, it seems that local clinicians often use the NICE guidelines available from the United Kingdom and follow international recommendations and consensus papers (e.g., published by European Psychiatric Association)6. While this approach may work for many clinicians, those clinicians who are not familiar with English language or know where to locate these documents will struggle to keep up to date with recommendations.

Two interventions, namely family therapy and psychoeducation (both developed in the USA), are recommended by most treatment guidelines from SEE countries. In 9 out of 12 countries, family therapy is available in the leading psychiatric institution, meaning that staff are trained and the intervention is on the service price list, indicating good implementation. The same is true for psychoeducation in 5 out of 12 countries. The evidence-base for these interventions seems to be stronger than for other interventions included in the studied guidelines. A meta-analysis of 25 trials examining family interventions—involving relatives in treatment and helping them to cope better with the patient’s illness—found a 20% reduction in relapse32. A systematic review of 44 trails found that psychoeducation appeared to reduce relapse and readmission, and encouraged medication compliance, as well as reduced the length of hospital stay33. Despite having a strong evidence base derived from studies in other regions, there is complete lack of research in SEE countries that systematically study the effectiveness and implementation of these interventions. This might be the main barrier for implementation of these interventions in mental health services in SEE countries. Additional challenges in implementation of treatment guidelines include lack of resources and/or inadequate use of current resources34.

The main strength of the study is that it provided a comprehensive overview of non-pharmacological treatment in the SEE region. The region remains the ‘blind spot on the global mental health map’2 and this study has the potential to fill the knowledge gap. The research team originates from SEE, which facilitated in-depth understanding of contextual factors related to developing and implementing treatment guidelines in participating countries. The study looked at published treatment guidelines and aspects of implementations as reported by experts in each participating country. Although this approach prevents us from deriving definitive conclusions about the implementation of recommended interventions in clinical practice, it can be used as a starting point for future interventional research as well as in-depth exploration of implementation barriers and facilitators. Some of the identified interventions could not be regarded as mutually exclusive and researchers struggled to allocate them into non-overlapping categories (e.g., Bulgarian national guidelines list individual therapy and CBT as two different non-pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia). The study focused on effectiveness data for identified interventions and evidence from qualitative studies was not explored. Despite these limitations, the study findings can contribute to the advancement of treatment of individuals with schizophrenia.

Treatment guidelines should be written by national experts and based on research data. The SEE countries need systematic studies on the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and implementation of non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia. As they provide important instruction in treatment of schizophrenia, treatment guidelines should be regularly updated in order to provide relevant data. Consistent re-evaluation of treatment guidelines is necessary and should be informed by newly acquired data coming from recent research.

Treatment guidelines should be updated with information relative to the most appropriate timing and type of psychosocial intervention based on illness stage (i.e., first episode vs chronic patients), clinical characteristics (i.e., positive symptoms vs predominantly negative symptoms), and general level of functioning. In addition, guidelines should be presented to clinicians with instructions on how to properly implement recommended interventions. We suggest continuous medical education complementary to treatment guidelines in order to provide up-to-date treatment direction.

Institutions should offer suitable trainings to their staff in order to facilitate implementation of evidence-base supported non-pharmacological treatments recommended in the treatment guidelines. Furthermore, we recommend training staff in additional evidence-based treatments that are not necessarily included in the treatment guidelines.

To conclude, most SEE countries have developed treatment guidelines for treating individuals with schizophrenia. The focus of these guidelines is mainly on pharmacotherapy, with less attention dedicated to discussion of the premises and benefits of non-pharmacological interventions. The majority of recommended non-pharmacological interventions have a mixed or negative RCT evidence base, which is almost exclusively comprised of studies conducted outside SEE countries. The recommended interventions seem to be poorly implemented in mental health services, which indicates large variation in delivery of mental health care across services. Existence of treatment guidelines is not sufficient for non-pharmacological treatment implementation. A substantial step towards implementation would be to include these non-pharmacological treatments into the official service price lists. Considering the limitations of the treatment guidelines and their implementation, it is clear that more research is warranted in the field. This study can be used as the first step in further research into developing evidence-based treatment guidelines in SEE countries, and ensuring their implementation in clinical practice.

Methods

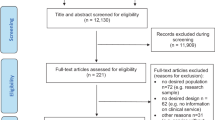

Treatment guidelines from each country were identified through online search or by country experts involved in the study. Desk and content analysis was used to ascertain fundamental features of identified treatment guidelines (title, publication year, and publisher) and to map recommended non-pharmacological interventions. Identified treatment guidelines were available in English or were translated into English by researchers (SR and TR).

Next, we assessed the evidence supporting recommended interventions and determined the source of evidence (e.g., SEE mental health services or elsewhere). The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and PubMed were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and PubMed were searched for meta-analyses and systematic reviews of identified non-pharmacological interventions published between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2020. The latest or the most comprehensive systematic review/meta-analysis/RCT for each non-pharmacological intervention was selected. Selected publications were assessed for inclusion of patients from any of the SEE countries. A narrative overview of current evidence base for identified interventions was drafted. The randomized-controlled trial evidence base was defined as ‘negative’ (intervention compared to standard treatment/active control was not effective or single RCT with significant limitations or meta-analysis with no effect), ‘mixed’ (RCTs indicating the intervention is effective/non-effective) and ‘positive’ (at least one RCT without significant limitations showed the intervention was effective).

Several aspects of the implementation of recommended interventions in each country were explored using a survey of experts. The experts were psychiatrists working in the leading national psychiatric institution in the country involved in clinical and/or research activities related to schizophrenia. The leading institution was defined as the largest teaching/training institution in the participating country’s capital city. The rationale for choosing these institutions was that they are more likely to provide non-pharmacological interventions for people with schizophrenia than other institutions in or outside capitals. The experts were identified through established research and professional networks. Each expert has a longstanding career in working with patients with schizophrenia and is recognized as a such in their respective country. One expert per country was invited and the response rate was 100%. The survey consisted of 20 questions. For each intervention identified in the analyzed guidelines, experts were asked to provide information whether the intervention was available in their institution and if the recommended intervention is included in the official service price list. Whether an intervention is on the official service price list enables monitoring of intervention delivery, facilitates the process of staff training, and ensures that the interventions are delivered by the properly trained staff. The survey was designed by the core research group (LIS, NJ, NS, TR, SR) and piloted with experts from five countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo (UN Resolution), Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia). Minor modifications concerning the formulation of questions and the survey’s layout were made before the survey was emailed to experts from the remaining seven SEE countries. Collected data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Ethical approvals and informed consents

All procedures were approved by the ethics committees of the respective institutions in the countries participating in the IMPULSE project (within which the present study has been conducted): Bosnia and Herzegovina (Klinički Centar Univerziteta u Sarajevu— 03-02-4216, JU Psihijatrijska bolnica Kantona Sarajevo i JU Zavod za bolesti ovisnosti Kantona Sarajevo 02.8—408/19), Serbia (Medicinski fakultet u Beogradu—2650/XII-20 and Specijalna bolnica ‘Dr Slavoljub Bakalovic’ Vršac—01-36/1), Kosovo (Hospital and University Clinical Service of Kosovo—2019-85), Republic of North Macedonia (Medicinski Fakultet pri UKIM vo Skopje—03-24219), and Montenegro (JZU Klinicki Centar Crne Gore—03/01-29304/1, ZU Specijalna Bolnica za Psihijatriju “Dobrota” Kotor and JZU Dom Zdravlja “Dr Nika Labovic” Berane—01-47).

The participants have not signed any written informed consent form due to the nature of the present study, which was mostly based on mental health policy analysis. The participants (i.e. experts) were informants who provided us with necessary information on mental healthcare services in their institutions and countries.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the collected data are available upon reasonable request from interested parties.

References

De Vries, A. & Klazinga, N. S. Mental health reform in post-conflict areas: a policy analysis based on experiences in Bosnia Herzegovina and Kosovo. Eur. J. Public Health 16, 246–251 (2006).

Winkler, P. et al. A blind spot on the global mental health map: a scoping review of 25 years’ development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and eastern Europe. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 634–642 (2017).

Priebe, S. et al. Community mental health centres initiated by the South-Eastern Europe Stability Pact: evaluation in seven countries. Community Ment Health J. 48, 352–362 (2012).

Stilo, S. A., Di Forti, M. & Murray, R. M. Environmental risk factors for schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatry 1, 457–466 (2012).

Sadock, B. J. & Sadoc, V. A., Ruiz P. Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 11th edn. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014).

NICE Treatment Guidelines for Managing Psychosis. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG178 (2014).

Lehman, A. F. et al. The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 30, 193–217 (2004).

DGPPN. S3-Leitlinie Psychosoziale Therapien bei schweren psychischen Erkrankungen. (AWMF Online & Springer, 2018).

Vita, A., Barlatti, S. & Sacchetti, E. Non-Pharmacological Strategies to Enhance Adherence and Continuity of Care in Schizophrenia; Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. (Springer, 2014).

Adams, C., Wilson, P. & Bagnall, A. M. Psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 9, 251–256 (2000).

Wampold, B. E. & Imel, Z. E. Counseling and Psychotherapy: The evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work (Routledge, 2015).

Malla, A. K. & Norman, R. M. Early intervention in schizophrenia and related disorders: advantages and pitfalls. Curr Opin Psychiatry 15, 17–23 (2002).

Chien, W. T., Leung, S. F., Yeung, F. K. & Wong, W. K. Current approaches to treatments for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, part II: psychosocial interventions and patient-focused perspectives in psychiatric care. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 9, 1463–1481 (2013).

Haddock, G. et al. An investigation of the implementation of NICE-recommended CBT interventions for people with schizophrenia. J Ment Health 23, 162–165 (2014).

Kocmur, M., Tavcar, R. & Zmitek, A. Priporocila in Smernice za zdravljenje z Shizofrenija. Ljubljana: Republiški strokovni kolegij za psihiatrijo (2000).

Priručnik psihosocijalne intervencije za osobe oboljele od shizofrenije, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Tuzla: Fenix. https://tkfenix.ba/download/prirucnik-psihosocijalne-intervencije-za-oboljele-osobe-od-shizofrenije/ (2012).

Bulgaria—The APA’s translated Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. (Bulgarian Psychiatric Association, 1998).

Psihički poremećaji sa psihozom i shizofrenija: Smjernice za psihosocijalne postupke i psihoterapiju. Hrvatska, Zagreb: HLZ I HPD. http://www.psihijatrija.hr/site/?p=2903 (2017).

Romoşan, F. & Lăzărescu, M. (eds). Schizofrenia şi tulburările de spectru. (Timişoara, Brumar 2012).

Protokolli i kujdesit diagnostik dhe terapeutik për skizofreninë, Albania. http://www.psihijatrija.hr/site/?p=2903 (2018).

Vodič za tretman shizofrenije. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo: Ministry of Health of Sarajevo Canton & Institute for Scientific Research and Development of Clinical University Center in Sarajevo (2006).

Κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες για τις μονάδες ΕΓΚΑΙΡΗΣ ΠΑΡΕΜΒΑΣΗΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΨΥΧΩΣΗ Κλάδος Έγκαιρης Παρέμβασης στην Ψύχωση της ΕΨΕ. https://psych.gr (2015).

Schizofrenia, primul episod psihotic: Protocol clinic national. Moldova. http://sanatatemintala.md/ro/legislatie/legislatia-nationala (2016).

Shizofrenija: Nacionalne smjernice dobre kliničke prakse. Montenegro, Podgorica: Ministarstvo zdravlja (2012).

Uputstvo za praktikuvanje na medicina zasnovana na dokazi pri tretman na šizofrenia. FYR Macedonia. http://zdravstvo.gov.mk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Sizofrenija.pdf (2013).

Nacionalni vodič za tretman shizofrenije. Republic of Serbia. http://www.zdravlje.gov.rs/downloads/2013/Novembar/VodicZaDijagnostikovanjeiLecenjeShizofreije.pdf (2013).

Oreški, S. et al. Kam in kako po pomoč vo duševni stiski. Ljubljana: Izobraćevalno raziskovalni inštitut (2016).

Rakitzi, S., Georgila, P., Efthimiou, K. & Mueller, D. R. Efficacy and feasibility of the integrated psychological therapy for outpatients with schizophrenia in Greece: Final results of a RCT. Psychiatry Res. 242, 137–143 (2016).

Štrkalj-Ivezić, S., Vrdoljak, M., Mužinić, L. & Agius, M. The impact of a rehabilitation day centre program for persons suffering from schizophrenia on quality of life, social functioning and self-esteem. Psychiatr. Danub. 25, 194–199 (2013).

Kinoshita, Y. et al. Supported employment for adults with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24030739/ (2013).

Woolf, S. H., Grol, R., Hutchinson, A., Eccles, M. & Grimshaw, J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 318, 527–530 (1999).

Pitschel-Walz, G. et al. The Effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia—a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 27, 73–92 (2001).

Xia, J., Merinder, L. B. & Belgamwar, M. R. Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 15, CD002831 (2011).

Rowlands, P. The NICE schizophrenia guidelines: The challenge of implementation. Adv Psychiatr Treat 10, 403–412 (2004).

Crawford, M. J. et al. Group art therapy as an adjunctive treatment for people with schizophrenia: Multicentre pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ 344, e846 (2012).

Gray, R. Adherence therapy—Working together to improve health: A treatment manual for healthcare workers. https://www.academia.edu/2436503/Adherence_therapy_manual (2003).

Gray, R. et al. Is adherence therapy an effective adjunct treatment for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 16, 1–12 (2016).

Blokdyk, G. Assertive community treatment: A complete guide. 5STARCooks (2019).

Nordén, T., Malm, U. & Norlander, T. Resource group assertive community treatment (RACT) as a tool of empowerment for clients with severe mental illness: a meta-analysis. Clini. Pract. Epidemiol. Mental Health 8, 144–151 (2012).

Powell, S. & Tahan, H. Case Management: A Practical Guide for Education and Practice. 4th edn. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2018).

Dieterich, M. et al. Intensive case management for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20927766/ (2010).

Smith, L., Nathan, P., Juniper, U., Kingsep, P. & Lim, L. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Psychotic Symptoms: A Therapist’s Manual. Perth, Australia. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Psychosis%20Manual.pdf (2003).

Jones, C. et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy plus standard care versus standard care for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, CD007964 (2018).

Haskins, E. C. Cognitive Rehabilitation Manual: Translating Evidence-Based Recommendations into Practice. (ACRM Publishing, 2012).

McGurk, S. R., Twamley, E. W., Sitzer, D. I., McHugo, G. J. & Mueser, K. T. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 164, 1791–1802 (2007).

Kemp, R. & David, A. Insight and compliancein. inTreatment Compliance and the Treatment Alliance in Serious Mental Illness (ed, Blackwell B.), 61–86 (Harwood Academic Publishers,1997).

O’Donnell, C. et al. Compliance therapy: a randomised controlled trial in schizophrenia. BMJ 327, 834 (2003).

Healios, Ltd. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/resources/family-intervention-service-manual-2494236205 (2014)

American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, 2nd edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 62, 625–683 (2008).

Foruzandeh, N. & Parvin, N. Occupational therapy for inpatients with chronic schizophrenia: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 10, 136–141 (2013).

Lloyd-Evans, B. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 14, 39 (2014).

McWilliams, N. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide (Guilford Press, 2004).

Malmberg, L. & Fenton, M. Individual psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis for schizophrenia and severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, CD001360 (2001).

Palli, A., Kalantzi-Azizi, A., Ploumpidis, D. N., Kontoangelos, K. & Economou, M. Group psychoeducational intervention in relatives of patients suffering from schizophrenia. Psychiatriki 25, 243–254 (2015).

Mooney, J. et al. Psychosocial interventions for the maintenance of weight loss in obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://www.cochrane.org/CD007153/ENDOC_psychosocial-interventions-maintenance-weight-loss-obese-adults (2015).

Riggs, P. D. Treating adolescents for substance abuse and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Sci Pract Perspect. 2, 18–29 (2003).

Fowler, D., Hodgekins, J. & French, P. Social recovery therapy in improving activity and social outcomes in early psychosis: Current evidence and longer term outcomes. Schizophr. Res. 203, 99–104 (2019).

Fowler, D. et al. Social recovery therapy: a treatment manual. Psychosis 11, 261–272 (2019).

Bellack, A. S., Mueser, T. K., Gingerich, S. & Agresta, J. Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia: a Step-by-Step Guide. 2nd edn. (The Gilford Press, 2004).

Turner, D. T. et al. A meta-analysis of social skills training and related interventions for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 475–491 (2018).

Novalis, P., Singer, V. & Peele R. Clinical Manual of Supportive Psychotherapy. 2nd edn. (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2020).

Buckley, L. A., Maayan, N., Soares-Weiser, K. & Adams, C. E. Supportive therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6486211/ (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded as part of the IMPULSE project under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 779334. The IMPULSE project has received funding through the “Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) prevention and management of mental disorders” (SCI-HCO-07-2017) funding call. The funder had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.I.S.—study design, manuscript preparation, data collection, research coordination; S.R. and T.R.—study design, manuscript preparation; N.S. —study design; S.T., A.D.K., A.P., M.R.K., I.I.V., S.S., A.B., A.N., S.B., A.L.P., N.M., and M.D.—data collection and interpretation; N.J.—manuscript preparation, data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stevović, L.I., Repišti, S., Radojičić, T. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for schizophrenia—analysis of treatment guidelines and implementation in 12 Southeast European countries. Schizophr 8, 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00226-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00226-y

This article is cited by

-

International rates of receipt of psychological therapy for psychosis and schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis

International Journal of Mental Health Systems (2023)