Abstract

Abnormal function and connectivity of the fronto-parietal network (FPN) have been documented in patients with schizophrenia, but studies are correlational. We applied repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and observed causal connectivity to the inferior parietal lobe (IPL). We hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia would have lower activation and slower reaction in the IPL following DLPFC stimulation. Thirteen patients with schizophrenia (SZ) and fourteen healthy controls subjects (HC) underwent rTMS at 10 Hz to the right DLPFC. Simultaneously, we measured brain activation in the IPL, represented as oxygenized hemoglobin (HbO) levels, using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). rTMS consisted of 20 trains of impulses at 10 Hz for 3 seconds, and 60 seconds waiting time. Using NIRSLab software, GLM was applied to estimate both hemodynamic response function (HRF) and its derivative. Following TMS to the DLPFC, SZ showed a smaller decrease in HbO levels in the bilateral IPL than HC (p = 0.05). Timecourse analysis revealed an immediate decrease in parietal HbO levels in HC, but not in SZ. This difference was significant (at a threshold level of p ≤ 0.05, with Bonferroni correction) for several time segments and channels in both rights and left IPL. Our findings suggest abnormal fronto-temporal connectivity in patients with schizophrenia, beyond a mere decrease or slowing of information processing. This is in line with the hypothesis of reduced fronto-parietal inhibition in schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness characterized by symptom dimensions such as positive and negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, and lack of insight into illness, amongst others1,2,3. At a neural level, schizophrenia is characterized by several brain abnormalities including dysconnectivity between brain areas4,5. Here, dysconnectivity refers to the wide range of abnormalities in both functional and anatomical brain connectivity. However, it is important to note that the abnormalities in the anatomical connectivity are not necessarily coupled linearly with abnormalities in functional connectivity6,7.

One of the most prominent deficits in schizophrenia is impairment in executive function. Executive function refers to higher-order cognitive processes necessary for daily functioning. The function includes sustained attention, i.e., vigilance, working memory, initiation, inhibition, set-shifting, and planning8,9. The neural correlates of the executive function are multifarious but consistently involve the fronto-parietal network (FPN) including the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and parietal cortex10.

This impairment in executive function in patients with schizophrenia is associated with aberrant function of the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)11, parietal cortex10, and the fronto-parietal network (FPN)12,13. The FPN, also called central executive network (CEN), is involved in cognitive control and central executive function14,15. Differences between healthy control subjects and patients with schizophrenia in the FPN have been observed in relation to cognitive deficits during resting state13,16, during specific functions such as working memory17,18,19,20, and also at the anatomical level21. However, fMRI-based techniques cannot determine causal relationships of interactions between brain regions22 because regular neuroimaging methods are correlative rather than causal in nature. In order to infer causality from neuroimaging data, a direct external manipulation of neural activity is required.

In this study we investigated the causal relationship between the DLPFC and IPL by combining repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) with functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). rTMS directly affects the stimulated brain region and connected brain areas23 and therefore can be used to investigate causal interactions between brain regions. fNIRS is a method to measure levels of oxygenized and deoxygenized hemoglobin (HbO and Hb) using light in the near-infrared range24,25. Such measurements are not affected by magnetic fields (as in the case of fMRI and EEG). rTMS stimulation to the DLPFC at 10 Hz, which is globally considered excitatory26, may cause either a putative increase or decrease of activation in the IPL, depending on whether connections are inhibitory or excitatory27.

In healthy people, rTMS at 10 Hz delivered to the left DLPFC was shown to alter cognitive control and ERP28 and to alter resting-state functional connectivity of a network that involved anterior cingulate cortex, IPL, inferior frontal cortex, and posterior temporal cortex29. 10 Hz rTMS stimulation to either left or right DLPFC improved reaction time and neuronal efficiency during working memory performance in healthy adult participants30. Yamanaka and colleagues investigated the effects of rTMS at 5 Hz delivered to either right or left IPL in healthy adults31. They found that stimulation to the right but not to the left IPL improved functioning during a spatial working memory task and affected HbO levels in the frontal cortex. This suggests that the effects of high-frequency rTMS on specific nodes of the fronto-parietal network affect other nodes of the network. Based on such evidence, we expect that 10 Hz rTMS to the right DLPFC will affect HbO levels in bilateral IPL in healthy volunteers.

Further, given that the anatomical fronto-parietal connectivity is deficient in schizophrenia21,32,33, we expect the deficiency will reflect on the speed of the connection from one region to another. Thus, we hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia would have a slower change of HbO levels in IPL as a consequence of DLPFC stimulation, which will be reflected in lower strength of the derivative of estimated haemodynamic response function (HRF) and insignificant difference in the first 30 seconds of the HbO timecourse.

Results

Demographics

There was no significant difference in age and gender between the groups Table 1. The two groups differed in education (t(2,25) = 2.58, p = 0.016). All patients used antipsychotics, listed in Table 1. As expected, there was a difference in psychophatology scores between HC and Schizophrenia patients (t(2,24) = −10.8, p < 0.001). PANSS measures were not collected for HC. In patient group all PANSS values were >0.

GLM

For GLM, HRF function was defined from 0 to 32s after the onset of the rTMS train. GLM revealed decreased levels of HbO in HC in bilateral IPL following the rTMS to the DLPFC (pbonferroni = 0.05; Fig. 1a). For the schizophrenia group, decreased levels of HbO in left IPL following the rTMS to the DLPFC were observed (puncorrected = 0.05; Fig. 1b). This decrease was not statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons. Patients differed from HC in HbO levels after rTMS, namely patients had higher levels of HbO compared to HC in the right hemisphere (at a significance level of p = 0.05, but not after correction for multiple comparisons; Fig. 1b). No difference in derivative of HRF was observed.

The red dots (sources) and yellow dots (detectors), same as in a, illustrate coverage by fNIRS. a GLM of HRF in HC threshold set at pbonferroni ≤ 0.05 (or p ≤ 0.002). There was a significant decrease of activation in both hemispheres. b GLM of HRF in schizophrenia patients. The decrease of activation is significant at the threshold of puncorrected ≤ 0.05 only in the left hemisphere. There was no significant change of activation in the right hemisphere. c GLM of HRF of HC vs schizophrenia patients. The difference in activation was significant at threshold of puncorrected ≤ 0.05. After correction for multiple comparisons only significant in the right hemisphere. There was no significant difference in activation in the left hemisphere.

Timecourses

In addition, there was a significant difference in timecourses between patients and HC following rTMS stimulation. Namely, while there was an immediate decrease in parietal HbO levels in HC, in SZ first an increase, followed by a decrease was observed (Figs. 2 and 3). This was significant (at a threshold level of pBonferroni = 0.05) for several time segments and channels in both right and left IPL (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the timecourses between HC and patients in the first time segment (0–5.1 s). The most significant difference was found in the ipsilateral IPL (the right IPL) in channels 2 (posterior), 10 (the most posterior), and 11–13 (superior channels), from 5 to 25 s. On the contralateral side, the significant difference occurred in two-time segments at two channels (25 and 26, the most superior and the most posterior channel).

Top incision: Right brain hemisphere with distributed optodes (red and yellow dots are sources and detectors, respectively) and the channels depicted in the panels below. Black numbers correspond to the channel numbers, blue lines illustrate the path over which the channel data was collected. Panels middle and below: Solid lines represent grand averages of time courses and shaded areas represent standard error of mean (S.E.M.): red—healthy controls, blue—patients with schizophrenia. Here we depicted representative channels from ipsilateral hemisphere: Ch 2 posterior part of IPL, Ch 5—inferior part of IPL, Ch 10—superior part of IPL and 12 central part of IPL.

Top incision: Left brain hemisphere with distributed optodes (red and yellow dots are sources and detectors, respectively) and the channels depicted in the panels below. Black numbers correspond to the channel numbers, blue lines illustrate the path over which the channel data were collected. Panels middle and below: Solid lines are grand average and shaded areas present standard error of mean (SEM)): red—healthy controls, blue—patients with schizophrenia. Here we depicted representative channels from contralateral hemisphere: Ch 16—central part of IPL, Ch 19—inferior part of IPL, Ch 25—posterior part of IPL and 26 superior part of IPL.

Discussion

In this study we examined causal functional brain connectivity from the right DLPFC towards bilateral IPL in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Causal perturbations to the DLPFC were delivered by trains of rTMS while the instigated brain activation of the IPL was measured using fNIRS. We observed differences in activation of bilateral IPL as a consequence of DLPFC stimulation in patients with schizophrenia as compared to the healthy control group. Namely, patients with schizophrenia had an initial increase in HbO levels followed by a decrease on some channels. This was in contrast with the HbO levels in HC, which showed an immediate decrease in HbO levels following the 3 s stimulation, which was maintained over a period of at least 30 seconds. In addition, the subsequent decrease in HbO levels at the later time point after the onset of the stimulus in schizophrenia patients was less intensive than the decrease in HC along the whole timecourse of one event. This finding might indicate different information processing from the frontal to parietal lobe in schizophrenia patients as compared to control participants. Our finding is in line with the idea of impaired fronto-parietal inhibition in schizophrenia, which has been proposed to underlie impairments in schizophrenia such as lack of cognitive control34,35,36.

Dorso-lateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) is involved in a variety of cognitive functions important for healthy perception and daily functioning. Among others, DPLFC plays a crucial role in working memory37 and inhibition control as demonstrated using the Go/NoGo task38,39. Abnormalities in DLPFC connectivity with parietal areas have been repeatedly reported for patients with schizophrenia40.

The DLPFC and IPL are connected directly, via superior longitudinal fasciculus41,42 most probably the second branch of it (SLF II). They are a major part of fronto-parietal executive network43,44. It is difficult to discern whether the anatomical connections from the DLPFC to IPL are inhibitory or excitatory because of the limitations of the measurement methods for humans. Namely, the non-invasive MRI-based DTI methods, used for example by Thiebaut de Schotten and colleagues41, can only follow thick fibers, without information about directionality (i.e., afferent or efferent). Anterograde and retrograde tracer studies are invasive and only possible in primates such as monkeys but specifically for the DLPFC connections to IPL they do not match between humans and monkeys42. Another possibility to investigate inhibition, excitation, and directional connectivity in humans is by using TMS. Rogasch and colleagues45 reviewed the studies of cortical inhibition, excitation, and connectivity using TMS in schizophrenia. The studies that were summarized used paired TMS pulses to produce short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) or long-interval intracortical inhibition (LICI). Both SICI and LICI represent the relative amplitude reduction of motor evoked potentials (MEPs) by subthreshold conditioning stimuli events where conditioning stimulus is presented either short time (for SICI) or long time (for LICI) before the test stimulus. They explained their findings in terms of levels of neurometabolites such as γ-amino butyric acid (GABA). Deficits in GABAergic activity have previously been reported in schizophrenia46. Rogasch and colleagues45 found GABAA receptor-mediated cortical inhibitory deficits in schizophrenia as well as in people with high risk and first-episode patients. These inhibitory deficits were both found on a local level (in PFC) and related to some long-range connections (including cortical, subcortical, and cerebellar connectivity). They suggested that the observed inhibitory deficits may lead to hyperexcitability in glutamatergic pathways and other network abnormalities in specific local neuronal populations that interact with long-range connections underlie cortical dysconnectivity in patients with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, none of the studies summarized were specific to DLPFC- IPL connection but rather related to motor cortices (see for example47). Nevertheless, they found the cortical inhibitory deficits in PFC in patients, which coupled with our findings and may suggest deficits in inhibition from DLPFC to IPL. In a similar fashion, Ferrarelli and colleagues48 used 0.4–0.6 Hz TMS stimuli delivered to several brain regions including the DLPFC and IPL while simultaneously measuring EEG in 20 healthy controls and 20 patients with schizophrenia. In addition to observing general slower prefrontal natural frequency of individuals with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls, they also found a reduction in TMS-related amplitude (ERSP) and synchronization (ITC) of beta/gamma-band EEG oscillations recorded at frontal/prefrontal sites in patients with schizophrenia compared with healthy control subjects. This was not observed for TMS delivered to parietal regions. The authors suggested that their findings argue against differences in neuronal excitability and likely reflect impairments in local cortical and thalamocortical circuits in schizophrenia. They also propose that a possible mechanism for the slowing of the prefrontal natural frequency might be due to deficits in GABAergic inhibition.

Given the disrupted fronto-parietal network in schizophrenia we expected to observe slower connectivity from frontal to parietal regions. We expected this to be reflected in the lower first derivative of the hemodynamic response. However, there was no difference for the first derivative. Surprisingly, the response was different in shape between groups. While for some channels a slower response was observed, for most of the channels we observed a different shape of the response. This suggests the intrinsically different fronto-parietal information processing in patients with schizophrenia as compared to healthy individuals.

We observed decreased HbO levels in parietal cortices as a consequence of stimulation in the healthy control group. The decreases in HbO levels suggest that there is an inhibitory stimuli arriving from DLPFC49,50. However, the relationship between the increase and decrease in HbO level is not linear with the activation of underlying neuronal tissue. The levels of HbO are rather associated with the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and the cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the state of various blood vessels50. The prolonged decrease in HbO was observed previously after electrical stimulation51, intermittent photic stimulation52, relaxing 2-dimensional images presentation53, reading and picture observation task54 or it can vary per subject performing the same task (reading)55. Clearly, more studies are needed, using fNIRS and possibly rTMS combined with fMRI, to further elucidate this finding.

There are several limitations of this study that should be mentioned here. First, this was a pilot study, and therefore the sample size is relatively limited. Nevertheless, our sample was large enough to detect substantial differences between the groups. Regardless, follow-up studies are needed to confirm and expand on these results. Second, due to the thickness of the optodes, we could not measure the brain activation at the stimulation site because the coil would be too far from the scalp. As a consequence, we could not directly establish increased or decreased activation in the DLPFC. In general, this type of stimulation delivered to the motor cortex causes increased motor cortex excitability, reflected in increased activation (reviewed in ref. 26). However, this is dependent on the intensity of the stimulation. Thus, we suggest that the excitation of the DLPFC caused a decreased activation in the IPL in our measurements, but we cannot confirm the former with our equipment. In addition, in this pilot study we did not use sham condition, nor was this study placebo-controlled. It may be possible that rTMS could cause flinching or tensing of facial muscles which in turn could cause movement artefacts. While these side-effects occurred in some patients during the subsequent iTBS treatment, we neither observe either flinching nor tensing during the rTMS stimulation reported here. Finally, all patients were using antipsychotics at the time of the study. The calculated dopamine equivalent dose56 was relatively homogeneous (66 ± 16)mg per day. Therefore, while antipsychotic medication influences the brain activation in several brain regions, although not consistently in the DLPFC57,58, our study is not suitable to investigate the effects of medication. Future studies could include patients that never received medication or are not using it at the time.

In conclusion, we investigated fronto-temporal connectivity using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with rTMS. In this way we could investigate effective connectivity, meaning an actual effect that the DLPFC exerts on the IPL in healthy controls and in patients with schizophrenia. We found that 10 Hz rTMS delivered to the right DLPFC induces decreased activation of the right and left IPL. In schizophrenia patients, however, this effect was opposite and in the same channels the stimulation produced increased activation. This suggests that there may be aberrant fronto-temporal connectivity in patients with schizophrenia, beyond mere decrease or slowing of information processing. Future brain stimulation studies should further investigate this observed opposite effect of rTMS on distal brain regions and possible implications for rTMS treatment strategies.

Methods

Participants

Thirteen patients and fourteen healthy controls (HC) underwent repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the right DLPFC. Patients also participated in a larger study into the treatment of apathy with intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) in schizophrenia after completing this pilot. Schizophrenia diagnosis was established by a clinician according to DSM V criteria. The diagnostic category was subsequently confirmed using the MINI plus interview59. The severity of symptoms was assessed using the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) and the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES). Exclusion criteria were comorbidities of severe mood or neurological disorders (including epilepsy or family history of epilepsy), brain surgery, MRI incompatibility, current alcohol or substance dependence disorder, or insufficient mastery of the Dutch language to perform tests in a valid way. The criteria for MRI compatibility include all the criteria for participation in the TMS study and were generally used in the larger study of apathy. Patients had to be at least 18 years of age.

Healthy controls had to be at least 18 years of age. Gender, age, and handedness were matched on a group level to the patients participating in the rTMS/NIRS session. Exclusion criteria were history or presence of psychiatric or neurological illness. All healthy controls and 12 patients were right-handed, one patient was ambidextrous.

Ethics

All study protocols were fully approved by the medical ethical board of the University Medical Center Groningen (METC; UMCG) with the reference number METc2013.137. All procedures were carried out according to the declaration of Helsinki.

This study is part of a clinical trial registered in the Netherlands Trial Register under Clinical Trial Registry Number 3805 (https://www.trialregister.nl/trial/3659).

Each participant in the study signed written informed consent, and only those who were fully capable of making their own decision regarding participation in the study were included.

Procedure

Upon arrival, healthy control participants filled in the remaining questionnaires (AES) before the rTMS procedure. Patients, had the questionnaires filled in on previous sessions. Subsequently, the site of the stimulation, right DLPFC, was defined as F4 electrode position (in the international 10/20 system) using the BramF3 software60. The software determines positions of F3 or F4 given the circumference, tragus-tragus, and inion-nasion distances. Then the F3 and F4 positions are defined by the distance from midline along circumference and distance from vertex along the y direction.

Next, the fNIRS cap was fitted and fNIRS optodes were placed. The participant was then laid in a comfortable dentist chair, to minimize Mayer-waves61. The operator agreed with the participant upon non-verbal communication methods in case of need, to avoid any talk, since the fNIRS sites were overlapping with the speech perception areas. The RTMS coil was placed above the F4 and the rTMS was delivered in a duration of ~20 min. Before the first rTMS train, a baseline fNIRS recording in a duration of a minimum 60 s was acquired.

A physician was available or on call, in case of medical intervention was required. Both patients and healthy control underwent rTMS without side-effects thus medical care was not required.

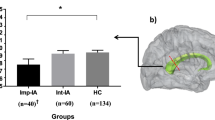

NIRS acquisition

Concentration changes of oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated (Hb) haemoglobin were recorded by NIRScout (DYNOT, Germany) using 8 source and 8 detector optodes. The light was emitted and recorded at two wavelengths (760 and 830 nm) at a sampling frequency of 7.8125 Hz. Optodes were placed over ipsilateral and contralateral IPL (see Fig. 4). The optodes were arranged in a 3 cm mesh and one optode was placed at a shorter distance (D5 on the ipsilateral and S5 on the contralateral hemisphere). The list of channels, optodes, and distances is presented in Table 3.

rTMS

rTMS was administered by using a Magstim Rapid2 stimulator (Medtronic, USA) with a 70 mm Double Air figure-of-eight coil over the F4 electrode position defined as described above. rTMS consisted of 20 trains of impulses at 10 Hz for 3 seconds, and 60 seconds waiting time. Simultaneously, we measured brain activation IPL using fNIRS. The intensity was set fixed to 60% of the maximal machine output for all participants. The intensity was fixed for all participants to minimize the burden to patients who subsequently participated in a study on the treatment of apathy.

NIRS data analysis

We estimated levels of Oxygenised haemoglobin (HbO) using NIRSLab software (NIRx Medical Technology, LLC; https://nirx.net/nirslab-1). First, data were checked for saturation (i.e., the introduction of non-number value in the absorption data due to detectors receiving too much light). No saturation was detected in our data pool. Then, data quality for each channel was examined. Channels with a coefficient of variance (CV) greater than 7.5% for either wavelength were excluded from the analysis. CV indicates the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), with lower values implying better SNR. It is calculated from the absorption data of each measurement wavelength using the following formula: CV = 100×(Standard Deviation)/Mean (Fig. 2).

a Distribution of sources (red dots) and detectors (yellow dots) projected on the brain surface. b Illustration of the TMS coil orientation. c Placement of the sources and detectors on the cap. d Measured channels: right—in the ipsilateral hemisphere (channels 1–15); and left in the contralateral hemisphere (channels 16–26).

Subsequently, the fNIRS data were checked for motion artifacts through visual inspection and corrected where appropriate. If there were channels with many uncorrectable artifacts within assessment trials were excluded from the analysis. This was needed only for one subject, for which only 7 blocks were included in the analysis. To remove other physiological artifacts (e.g., slow drifts, respiration), a band-pass filter was applied to the absorption data. A low-frequency cutoff of 0.01 Hz and a high-frequency cutoff of 0.2 Hz were used with a 15% roll-off width each. Finally, the absorption data were converted into concentration data the modified Beer-Lambert Law (mBLL): \(OD_\lambda = \left( {\varepsilon _{HbO_2}^\lambda \left[ {HbO_2} \right] + \varepsilon _{HbR}^\lambda \left[ {HbR} \right]} \right) \cdot DPF \cdot d + G\)62. Here, OD denotees optical density or absorption, λ the wavelength of the light, ε denotes the extinction coefficient, the d in the formula denotes the distance between the source and the detector, while G represents the loss of light intensity due to scattering. We used the absorption spectra provided by Gratzer and associates63 to determine the ε of HbO and Hb for each wavelength (see Fig. 3). DPF is the differential pathlength factor and the current study used the DPFs provided by Essenpreis and colleague64. Eventually, the changes of concentration values were calculated.

GLM was applied using both HRF and its derivative. t-test was used, with FDR correction, to compare beta values of HbO levels following rTMS stimulation. HRF and derivative were defined from 0 to 32s after the onset of the rTMS train. The highest and the lowest peaks of HRF were set at 6 and 16 s, respectively, and the design matrix was filtered using Gaussian function with 4 mm FWHM.

Average timecourses were calculated per participant per time point from 5 seconds before the onset of the stimulation burst to 60 seconds after. t-test was used with bonferroni correction to compare time segments between the two groups.

All the statistical tests were, where relevant (such as t-tests), two-sided.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Frith, C. D., Blakemore, S. & Wolpert, D. M. Explaining the symptoms of schizophrenia: abnormalities in the awareness of action. Brain Res. Rev. 31, 357–363 (2000).

Andreasen, N. C., Arndt, S., Alliger, R., Miller, D. & Flaum, M. Symptoms of schizophrenia: methods, meanings, and mechanisms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52, 341–351 (1995).

Liddle, P. F. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: a re-examination of the positive-negative dichotomy. Br. J. Psychiatry 151, 145–51. (1987).

Friston, K. J. & Frith, C. D. Schizophrenia: a disconnection syndrome? Clin. Neurosci. 3, 89–97 (1995).

Stephan, K. E., Friston, K. J. & Frith, C. D. Dysconnection in schizophrenia: from abnormal synaptic plasticity to failures of self-monitoring. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 509–527 (2009).

Hillary, F. G. et al. Hyperconnectivity is a fundamental response to neurological disruption. Neuropsychology 29, 59–75 (2015).

Koch, M. A., Norris, D. G. & Hund-Georgiadis, M. An investigation of functional and anatomical connectivity using magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 16, 241–250 (2002).

Goldman-Rakic, P. S. Regional and cellular fractionation of working memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13473–80. (1996).

Smith, E. E. & Jonides, J. Storage and executive processes in the frontal lobes. Science 283, 1657–1661 (1999).

Niendam, T. A. et al. Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 241–268 (2012).

Weinberger, D. R., Berman, K. F. & Zec, R. F. Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43, 114–124 (1986).

Deserno, L., Sterzer, P., Wüstenberg, T., Heinz, A. & Schlagenhauf, F. Reduced prefrontal-parietal effective cconnectivity and working memory deficits in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 32, 12–20 (2012).

Fryer, S. L. et al. Relating intrinsic low-frequency BOLD cortical oscillations to cognition in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2705–2714 (2015).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Zanto, T. P. & Gazzaley, A. Fronto-parietal network: flexible hub of cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 602–603 (2013).

Rotarska-Jagiela, A. et al. Resting-state functional network correlates of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 117, 21–30 (2010).

Sheffield, J. M. et al. Fronto-parietal and cingulo-opercular network integrity and cognition in health and schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia 73, 82–93 (2015).

Meda, S. A., Stevens, M. C., Folley, B. S., Calhoun, V. D. & Pearlson, G. D. Evidence for anomalous network connectivity during working memory encoding in schizophrenia: an ICA based analysis. PLoS ONE 4, e7911 (2009).

Honey, G. D., Bullmore, E. T. & Sharma, T. De-coupling of cognitive performance and cerebral functional response during working memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 53, 45–56 (2002).

Henseler, I., Falkai, P. & Gruber, O. Disturbed functional connectivity within brain networks subserving domain-specific subcomponents of working memory in schizophrenia: Relation to performance and clinical symptoms. J. Psychiatry Res. 44, 364–372 (2010).

Rotarska-Jagiela, A. et al. Anatomical brain connectivity and positive symptoms of schizophrenia: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 174, 9–16 (2009).

Chen, A. C. et al. Causal interactions between fronto-parietal central executive and default-mode networks in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19944–19949 (2013).

Valchev, N. et al. cTBS delivered to the left somatosensory cortex changes its functional connectivity during rest. Neuroimage 114, 386–397 (2015).

Obrig, H. & Villringer, A. Beyond the visible—imaging the human brain with light. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23, 1–18 (2003).

Quaresima, V. & Ferrari, M. A mini-review on functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS): where do we stand, and where should We Go? Photonics 6, 87 (2019).

Klomjai, W., Katz, R. & Lackmy-Vallée, A. Basic principles of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and repetitive TMS (rTMS). Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 58, 208–213 (2015).

Curtin, A. et al. A systematic review of integrated functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies. Front. Neurosci. 13, 84 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. The effects of high-frequency rTMS over the left DLPFC on cognitive control in young healthy participants. PLoS ONE 12, e0179430 (2017).

Tik, M. et al. Towards understanding rTMS mechanism of action: stimulation of the DLPFC causes network-specific increase in functional connectivity. Neuroimage 162, 289–296 (2017).

Preston, G., Anderson, E., Silva, C., Goldberg, T. & Wassermann, E. M. Effects of 10 Hz rTMS on the neural efficiency of working memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci 22, 447–456 (2010).

Yamanaka, K., Yamagata, B., Tomioka, H., Kawasaki, S. & Mimura, M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the parietal cortex facilitates spatial working memory: near-infrared spectroscopy study. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1037–1045 (2010).

Ćurčić-Blake, B. et al. Not on speaking terms: hallucinations and structural network disconnectivity in schizophrenia. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 407–418 (2015).

Ćurčić-Blake, B., van der Meer, L., Pijnenborg, G. H., David, A. S. & Aleman, A. Insight and psychosis: functional and anatomical brain connectivity and self-reflection in Schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 4859–4868 (2015).

Barch, D. M. et al. Selective deficits in prefrontal cortex function in medication-naive patients with schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 280–288 (2001).

Minzenberg, M. J., Laird, A. R., Thelen, S., Carter, C. S. & Glahn, D. C. Meta-analysis of 41 functional neuroimaging studies of executive function in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 811–822 (2009).

Lisman, J. Excitation, inhibition, local oscillations, or large-scale loops: what causes the symptoms of schizophrenia? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 22, 537–544 (2012).

Curtis, C. E. & D’Esposito, M. Persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex during working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 415–423 (2003).

Menon, V., Adleman, N. E., White, C. D., Glover, G. H. & Reiss, A. L. Error-related brain activation during a Go/NoGo response inhibition task. Hum. Brain Mapp. 12, 131–143 (2001).

Simmonds, D. J., Pekar, J. J. & Mostofsky, S. H. Meta-analysis of Go/No-go tasks demonstrating that fMRI activation associated with response inhibition is task-dependent. Neuropsychologia 46, 224–232 (2008).

Chechko, N. et al. Differential resting-state connectivity patterns of the right anterior and posterior dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (DLPFC) in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 9, 211 (2018).

Thiebaut de Schotten, M., Dell’Acqua, F., Valabregue, R. & Catani, M. Monkey to human comparative anatomy of the frontal lobe association tracts. Cortex 48, 82–96 (2012).

Petrides, M., Tomaiuolo, F., Yeterian, E. H. & Pandya, D. N. The prefrontal cortex: comparative architectonic organization in the human and the macaque monkey brains. Cortex 48, 46–57 (2012).

Meyer-Lindenberg, A. et al. Evidence for abnormal cortical functional connectivity during working memory in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 1809–1817 (2001).

Forbes, N. F., Carrick, L. A., McIntosh, A. M. & Lawrie, S. M. Working memory in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 39, 889–905 (2009).

Rogasch, N. C., Daskalakis, Z. J. & Fitzgerald, P. B. Cortical inhibition, excitation, and connectivity in schizophrenia: a review of insights from transcranial magnetic stimulation. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 685–696 (2014).

Lewis, D. A., Hashimoto, T. & Volk, D. W. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 312–324 (2005).

Farzan, F. et al. Evidence for gamma inhibition deficits in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Brain 133, 1505–1514 (2010).

Ferrarelli, F. et al. Reduced natural oscillatory frequency of frontal thalamocortical circuits in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 766–774 (2012).

Huber, L. et al. Investigation of the neurovascular coupling in positive and negative BOLD responses in human brain at 7T. Neuroimage 97, 349–362 (2014).

Hoshi, Y. Hemodynamic signals in fNIRS. Prog. Brain Res. 225, 153–179 (2016).

Seiyama, A. et al. Circulatory basis of fMRI signals: relationship between changes in the hemodynamic parameters and BOLD signal intensity. Neuroimage 21, 1204–1214 (2004).

Maggioni, E. et al. Investigation of negative BOLD responses in human brain through NIRS technique. A visual stimulation study. Neuroimage 108, 410–422 (2015).

Igarashi, M. et al. Effects of stimulation by three-dimensional natural images on prefrontal cortex and autonomic nerve activity: a comparison with stimulation using two-dimensional images. Cogn. Process. 15, 551–556 (2014).

Fallgatter, A. J., Muller, T. J. & Strik, W. K. Prefrontal hypooxygenation during language processing assessed with near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuropsychobiology 37, 215–218 (1998).

Liu, K. R., Borrett, D. S., Cheng, A., Gasparro, D. & Kwan, H. C. Near-infrared spectroscopy study of language activated hyper- and hypo-oxygenation in human prefrontal cortex. Int. J. Neurosci. 118, 657–666 (2008).

Lako, I. M. et al. Estimating dopamine D2 receptor occupancy for doses of 8 antipsychotics: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 33, 675–81 (2013).

Snitz, B. E. et al. Lateral and medial hypofrontality in first-episode schizophrenia: functional activity in a medication-naive state and effects of short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 2322–2329 (2005).

da Silva Alves, F. & Figee, M. The revised dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: evidence from pharmacological MRI studies with atypical antipsychotic medication. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 41, 121–132 (2008).

Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59(Suppl 20), 22–33 (1998).

Mir-Moghtadaei, A. et al. Concordance between BeamF3 and MRI-neuronavigated target sites for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Brain Stimul. 8, 965–973 (2015).

Tachtsidis, I. et al. Investigation of cerebral haemodynamics by near-infrared spectroscopy in young healthy volunteers reveals posture-dependent spontaneous oscillations. Physiol. Meas. 25, 437–445 (2004).

Zhao, Y., Qiu, L., Sun, Y., Huang, C. & Li, T. Optimal hemoglobin extinction coefficient data set for near-infrared spectroscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 5151–5159 (2017).

Gratzer W. B. & Kollias N. Tabulated molar extinction coefficient for hemoglobin in water, vol. 5, 50–161 (Wellman Laboratories, Harvard Medical School, 1999).

Essenpreis, M. et al. Spectral dependence of temporal point spread functions in human tissues. Appl. Opt. 32, 418–425 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a VICI grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) grant no. 453.11.004 and an ERC Consolidator grant, project no. 312787 to A.A. We thank N. Klaasen, L. Bais, and N.M. Maurits for their support during the preparation of the study. We thank M. Thioux for help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Ć.B. made substantial contributions to the design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, and have drafted the work and substantively revised. A.A. made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, data interpretation, and substantively revised the manuscript. C.K. made substantial contribution to the design of the work, and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and the accuracy and integrity of presented work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ćurčić-Blake, B., Kos, C. & Aleman, A. Causal connectivity from right DLPFC to IPL in schizophrenia patients: a pilot study. Schizophr 8, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00216-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00216-0