Abstract

Lifshitz transition (LT) refers to an abrupt change in the electronic structure and Fermi surface and is associated to a variety of emergent quantum phenomena. Amongst the LTs observed in known materials, the field-induced LT has been rare and its origin remains elusive. To understand the origin of field-induced LT, it is important to extend the material basis beyond the usual setting of heavy fermion metals. Here, we report on a field-induced LT in PrAlSi, a magnetic Weyl semimetal candidate with localized 4f electrons, through a study of magnetotransport up to 55 T. The quantum oscillation analysis reveals that across a threshold field B* ≈ 14.5 T the oscillation frequency (F1 = 43 T) is replaced by two new frequencies (F2 = 62 T and F3 = 103 T). Strikingly, the LT occurs well below the quantum limit, with obvious temperature-dependent oscillation frequency and field-dependent cyclotron mass. Our work not only enriches the rare examples of field-induced LTs but also paves the way for further investigation of the interplay among topology, magnetism, and electronic correlation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Lifshitz transition (LT) has received renewed attention in condensed matter physics. An LT1 is an electronic topological transition of the Fermi surface (FS) driven by the variation of the band structure and/or the Fermi energy. Since such a transition does not necessarily require simultaneous symmetry breaking, and meanwhile, it can occur at T = 0, and be tuned by parameters other than temperature (such as pressure, strain, doping, magnetic field, etc.)1,2, it, therefore, can be deemed as a topological quantum phase transition. In the vicinity of Lifshitz transitions, many peculiar emergent phenomena may appear, such as van-Hove singularity, non-Fermi-liquid behavior, unconventional superconductivity, and so on (e.g. refs. 3,4).

Compared with a number of cases tuned by doping or pressure that have been widely seen in topological systems5,6, cuprate superconductors7,8, iron pnictides superconductors9,10, and other strongly correlated materials3,11, the examples of LT driven by a magnetic field are rare. This is because the energy scale of a laboratory magnetic field, in the order of 1–10 meV, is much smaller than the characteristic energy scale of most metals (~102−103 meV). Only in a few cases, mostly limited in heavy-fermion (HF) metals12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, the hybridization between conduction electrons and localized f electrons leads to narrow renormalized bands with a small Fermi energy and thus the Zeeman term can be sufficiently strong to shift the spin-split FS15. Recently, field-induced LTs were also observed in some low Fermi energy non-magnetic semimetals, such as bismuth21, TaP22, and TaAs23, wherein magnetic field beyond the quantum limit can empty a Dirac or Weyl pocket with small Fermi energy. However, in these cases, no additional Fermi pocket emerges and the carriers of the empty pocket were transferred to other pockets (previously existing).

Here we present a new example of field-induced LT beyond heavy-fermion systems in the magnetic Weyl semimetal candidate PrAlSi, by a systematic study of quantum oscillation (QO) effect with the magnetic field extending up to 55 T. We observe a single frequency (F1 = 43 T) below a critical field of B* = 14.5 T, in agreement with what was previously reported24. Above B*, we see clearly the emergence of two new frequencies (F2 = 62 T and F3 = 103 T) and the disappearance of the original F1. We exclude the possibility of magnetic breakdown and identify B* as a critical point where the field-induced LT occurs. By comparing the reported Fermi surface of NdAlSi and the theoretical calculation of PrAlSi, we conclude that the LT occurs in the hole-like Weyl pockets along the direction of Γ−X of the Brillouin zone (BZ, hereafter). Our work not only enriches the rare examples of field-induced LTs but also paves the way for further investigation on the interplay among topology, magnetism, and electronic correlation.

The RAlX family (R = rare earth and X = Si or Ge) compounds have recently been proposed to host ideal candidates of magnetic Weyl semimetals25,26, and provide a platform to investigate the interaction between magnetism and Weyl physics27,28,29,30,31. They crystallize in a tetragonal structure with the noncentrosymmetric space group symmetry of I41/md (No. 109). One advantage of this family is that Weyl nodes generated by inversion breaking are robust and can be shifted by the Zeeman coupling in the k space25. Several intriguing physical properties have been observed in this family. The list includes the coexistence of type-I and type-II Weyl fermion in LaAlSi32 and LaAlGe33, topological Hall effect in CeAlGe34, anisotropic anomalous Hall effect in CeAlSi35, and Weyl-driven collective magnetism in NdAlSi36. The compound PrAlSi studied here is a ferromagnetic semimetal with Curie temperature TC ~ 18 K. A recent work based on static field (9 T) transport measurements by Lyu et al. revealed a large anomalous Hall conductivity ~2000 Ω−1 cm−1 and an unusual temperature dependence of QO with a single frequency24.

Results

Experimental results and analysis

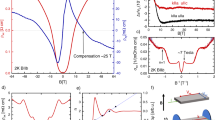

High-quality single crystals of PrAlSi were synthesized using the flux method. The inset of Fig. 1a shows the crystal structure of PrAlSi with the magnetic moments of Pr easily orientated along the c-axis after the application of a small field24. In our transport measurements, the magnetic field was along the c-axis and the electrical current was along the b-axis (more details are presented in the “Methods” section and Supplemental Material). Figure 1a shows magnetoresistance measured in the static field at 2 K (red curve) and pulsed field at 1.8 K (black curve). Normalized magnetoresistance (ρ(B)−ρ(0))/ρ(0) reaches 116 at 55 T and remains non-saturating. The purple dashed line corresponds to B1.7. Figure 1b presents the oscillatory part of the longitudinal resistivity Δρ(B), obtained by subtracting a smooth background from the measured ρ(B) (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for more raw data). At low temperatures, oscillations are visible above the field as low as 3 T, indicating the good quality of the sample. The rough Dingle mobility of 1/Bc = 0.33 T−1 is close to the average mobility of 0.26 m2/V s yielded from the amplitude of the quadratic low-field magnetoresistance (see the inset of Supplementary Fig. 2a). The single-frequency QO for static field measurements retains until temperature down to 80 mK. A more complex pattern emerges when the larger magnetic field is applied, as seen in Fig. 1c.

a The field-dependent of MR measured under a static field at 2 K and a pulsed-field at 1.8 K. The inset is the crystal structure(I41/md) of PrAlSi as the magnetic field easily polarizes the moments of Pr along the c-axis. b Field dependence of the oscillatory part of magnetoresistance Δρ(B) in low magnetic field measured under static field, showing only a single QO frequency. The experiments were carried out with a Leiden dilution refrigerator (14 T) at 80 mK and with a refrigerator of Oxford Instrument (16 T) at T = 10, 17, and 25 K. c Δρ(B) in high magnetic field measured by the pulsed magnetic field, showing more QO frequencies with a complex pattern.

Figure 2a and b show the results of the fast Fourier transformation (FFT) of the oscillatory part of the magnetoresistance Δρ as a function of 1/B. The SdH frequencies extracted from low-field (B < 14.5 T) and high-field (B > 14.5 T) data display a dramatic difference. Note that, since this compound is ferromagnetic, we took into the demagnetization factor to correct the applied field in all the analyses of SdH effect (see Section 9 of the Supplemental Material). We identified B* = 14.5 T as a critical field, after checking several fields close to B*. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, we have intercepted a field with different values, 10, 14, 14.5, 15, and 20 T for the segmented FFT analyses. We can see the crossover from the lower QO frequency to the two higher QO frequencies as the segment changes between the 5.7 T and the selected field. Two higher QO peaks emerge when we segment the field at 20 T and we note that the low QO peaks persist because of the inclusion of the low-field QOs below 14.5 T. From the comparison of the segmented FFT analyses, 14.5 T was determined as the field of the LT. There is only one fundamental frequency in the FFT spectrum until down to 80 mK below B* (see Fig. 2a). It should be noted that F1 gradually decreases with temperature, changing from 43 T at 80 mK to 32 T at 35 K, as shown in the inset. Similar temperature dependence in F1 was also reported in earlier work on PrAlSi24, whereas the values of F1 are relatively smaller than ours. We attribute this discrepancy to the difference in stoichiometry19. Figure 2b shows that above B* there are two new QO frequencies (F2 = 62 T, F3 = 103 T) and their high-order harmonics. Such a change in the Fermi surface is also manifested in the effective cyclotron mass m*. The value of m* for each frequency can be deduced from the fitting of FFT amplitude according to the temperature damping factor, and this yields the small m* = 0.08me for F1 (with field range 5.7–14.5 T), and 0.23me and 0.28me for F2 and F3, respectively, where me is the mass of a free electron. Interestingly, a careful look into the temperature dependence of the amplitude of the oscillatory peak leads to the fact that the effective mass is enhanced 2-fold between 2.8 T and B*, as shown in Fig. 2c. This feature is reminiscent of HF systems displaying an LT and will be discussed more later on. The effective masses of F2 and F3 as the function of a field higher than B* are absent here, mainly because it is rather difficult to extract the exact amplitude of entangled peaks in the oscillatory part from two frequencies and their harmonic terms. More explanation about the effective mass mentioned above is exhibited in Supplementary Fig. 5. The Fermi energy of the band corresponding to F1 is then estimated εF ~ 125 meV.

a, b The frequency (T) dependence of the fast-Fourier-transformation amplitude of SdH oscillations measured at various temperatures with B∥c in the pulsed field. With the field lower than 14.5 T, only one fundamental frequency exists in (a). Two main higher frequencies and harmonic terms are shown in b with the field above 14.5 T. The inset shows the temperature-dependent frequency F1 extracted from (a). c The corresponding effective mass of F1 as a function of magnetic field B was obtained from the analysis of the QO peaks in a static field.

To further demonstrate the field-induced Fermi surface change near B* = 14.5 T, we performed Lifshitz–Kosevich (LK) fitting on Δρ(B) measured under the pulsed field. We notice that all the analyzed FFT data are from the pulsed fields. More details can be found in Section 4 of the Supplementary Material. As is shown in Fig. 3a, the Δρ for the field below B* can be well reproduced by the LK fitting with a single F1 (cf. the red dot line). However, such a fitting collapse when the field exceeds B*. This problem can be fixed in an alternate fitting by employing both F2 and F3, seeing the blue dot line in Fig. 3b. Noteworthy that this 2-frequency LK fitting fails in the low-field window, implying that F2 and F3 appear only in the high-field range.

Inverse field dependence of the oscillatory magnetoresistance measured at 1.8 K with pulsed-field and at 2 K with static field are depicted as black and green lines, respectively. Note that the L–K fitting with a single frequency of 43 T reproduces the SdH oscillations nicely for the field below B*, but fails for B > B*, as shown in panel (a). A multi-frequency L–K fitting by employing both F2 and F3 describes Δρ(B) reasonably well for B > B*, seeing panel (b).

Thus, the variation of QO frequencies with the disappearance of 43 T and the emergence of 62 and 103 T clearly point to the change in Fermi surface topology, viz an LT. Firstly, we can rule out magnetic breakdown as the origin, because there is no extra QO frequency (19 T and 60 T) in the low-field range even for temperature as low as 80 mK. Moreover, the peak with the frequency of 43 T does not persist under a high magnetic field, either. Secondly, we can also exclude a metamagnetic transition as the driver of this process. Figure 4a shows the field dependence of magnetization at 2 K with the magnetic field applied along the c-axis. One clearly finds that the magnetization saturates to ~3.1μB/Pr at a small field 0.48 T, and no additional transition can be resolved nearby 14.5 T except for some traces of de Haas–van Alphen oscillations (inset of Fig. 4a). This is different from the case of NdAlSi, where a magnetic transition to the final Weyl-mediated helical magnetism leads to a change in QO frequency36.

a The magnetization of PrAlSi with the magnetic field applied along the c-axis, the inset is the enlarged part with evident QOs. b The black and red lines are the first derivative of the MR and Hall resistivities measured under a pulsed field which could provide more information beyond the critical field. The violet dotted lines guided by eyes suggest the change of slopes in both of them at the B*. c The field dependence of Hall resistance at 1.8 K along with two fitting curves with the two-band model. The red and blue curves correspond to the fits to the low-field and high-field, respectively.

In order to further clarify this field-induced LT, it is helpful to estimate the density of carriers of each Fermi pocket. According to the Lifshitz–Onsager relation, F = (ℏ/2πe)AF, where ℏ is Planck’s constant and \({A}_{{\rm {F}}}=\pi {k}_{{\rm {F}}}^{2}\) is an extremal cross-sectional area of the Fermi surface perpendicular to the field with Fermi wave vector kF. The bands become non-degenerate due to spin–orbit coupling36. Assuming these Fermi pockets are spheres, we find that the LT wipes out \({n}_{{{\rm {F}}}_{1}}\)= 3.2 × 1018 cm−3 and produces \({n}_{{{\rm {F}}}_{2}}\)= 5.5 × 1018 cm−3 and \({n}_{{{\rm {F}}}_{3}}\)= 1.2 × 1019 cm−3 per four pockets. Note that the total number of pockets would be a multiple of 4, due to the symmetric requirement (see below).

The total carrier density of the hole and electron can be also extracted by fitting the Hall resistivity with the two-band model,

Here, n and μ represent carrier density and mobility, and the subscripts h and e denote hole and electron, respectively. We obtain nh = 4.3 × 1019 cm−3, ne = 5.3 × 1019 cm−3, μh = 0.18 m2/V s and μe = 0.22 m2/V s. These values fit both Hall resistivity and magnetoresistivity reasonably well up to B* (see Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 7). The deduced mobilities are also close to the value obtained from quantum oscillations and magnetoresistance. The average zero-field mobility 〈μ〉 extracted from the residual resistivity ρ0 = 15 μΩ cm is about 0.5 m2/V s, slightly larger than the finite-field mobility. Such a discrepancy has been observed in other semimetals37,38 and attributed to the field-induced mobility reduction. The carrier densities of hole and electron are within 10% of the compensation 2[nenh/(ne + nh)], compared to ~4% in bismuth39 and WTe240. This near compensation would explain the observed unsaturated magnetoresistance. The slight excess in the hole may result from uncontrollable doping which could be also the reason for the sample dependence of F1 as discussed above.

This fit, which properly works up to B* (shown by a black arrow in Fig. 4c), fails above B*. The change occurring at B* is evident in Fig. 4b, which shows the first derivative of the longitudinal and Hall resistivities. The violet dotted lines demonstrate the apparent change of slope in MR and Hall resistivities at 14.5 T. We let ∣nh−ne∣ to stay constant across B*, in order to respect the Luttinger theorem41. We infer that F2 and F3 should correspond to carriers of opposite signs with a density difference of \(| {n}_{{{F}}_{3}}-{n}_{{{F}}_{2}}| =6.5\times 1{0}^{18}\) cm−3. Assuming that there are 8 pockets for F1 (\(2{n}_{{F}_{1}}\)= 6.4 × 1018 cm−3), would be compatible with the Luttinger theorem. Both types of carriers increase by about 0.6 × 1019 cm−3 (\({n}_{{F}_{3}}-2{n}_{{F}_{1}}\) and \({n}_{{F}_{2}}\), respectively). By fitting the Hall resistivity curve with nh = 4.9 × 1019 cm−3 and ne = 5.9 × 1019 cm−3, we obtain μh = 0.05(1) m2/V s and μe = 0.16(1) m2/V s. This is shown in Fig. 4c with a blue line. The mobility (\(\mu =\frac{e\tau }{{m}^{* }}\)) of holes drop (~72%) more than that of electron (~27%), implying the sign of F1 with a small mass should be hole-like, since its mass increases by 2.5 times by assuming the same scattering time τ. We conclude that F2 has an electron-like sign and F3 is a hole-like one. Thus, each hole pocket (F1) evolves into a larger hole pocket (F3) and an additional electron pocket (F2). This indicates the existence of a van-Hove singularity (saddle point) in this system.

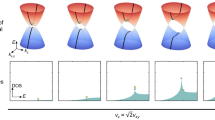

To get more information about the Fermi surface of PrAlSi, we performed the measurements of angular-dependent MR with a pulsed magnetic field at T = 1.8 K. Figure 5a shows the oscillatory component extracted by subtracting the smooth background from the MR measured at different θ, which is defined as the angle between the c-axis and the magnetic field, and the current was along b-axis as shown in the inset (see the Supplementary Fig. 10 for the raw MR data). The SdH oscillations evolve systematically and can be observed in all angles as the magnetic field is rotated from θ = 0° to θ = 87°. Figure 5b and c present the segmented FFT spectra for different angles θ. The inset of Fig. 5b shows the critical fields at various angles, which indicates that the LT also envolves with θ. We determined the B* as the same method mentioned above and the detail is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The oscillation frequency F1 shown in Fig. 5b is weakly dependent on the angle, indeed indicating a nearly spherical Fermi surface of this band and the evolution of angle-dependent oscillation frequencies F2, F3 and their harmonic terms shown in Fig. 5c. According to the experimental results, Fig. 5d presents the angle dependence of the quantum oscillation F1 which is shown as black symbols as well as Fα, Fβ, Fγ and Fη are the calculated frequencies obtained from the SKEAF program42. The Fermi level was shifted with 3 meV in the calculation because of the uncertain doping. The Fα is quite close to the observed F1. Whereas the higher frequencies obtained from the calculation are not been observed by experiment in our case, may be due to the low mobility of these bands.

a Background-subtracted SdH oscillatory part as a function of 1/B at T = 1.8 K under various angles. The inset on the top is the schematic diagram of the measurements. b, c The FFT spectra for different angles and magnetic field ranges and the data are shifted along the vertical axis for clarity. The inset in graph b displays the critical fields of every angle and the error bars are defined as standard deviation. d The angular dependence of the corresponding measured oscillation frequency of F1 pocket (black solid symbol) as well as the calculated frequencies Fα, Fβ, Fγ and Fη. e and f Schematic illustration of the Lifshitz transition in the BZ by the sketch of Fermi pockets which correspond to (b) and (c), respectively. Two tiny hole pockets (in orange) with F1 = 43 T located along the sides of Γ−X transform into one electron pocket in green with F2 = 62 T and one hole pocket in violet with F3 = 103 T after LT, implying the existence of a van-Hove singularity. The pockets along Γ−S are not shown here (see Supplementary Fig. 9). In graph e, the projection of two pairs of Weyl points around the Γ−X line in the BZ is illustrated, in which W1 and W2 are indicated. Weyl points with opposite chiralities are marked as red and blue dots.

Next, we tried to locate these pockets in the BZ, and our similar calculation results (see Supplementary Fig. 11). The electronic structure also resembles that of NdAlSi36. Since the center of the BZ is not occupied, symmetry imposes four-fold degeneracy of each pocket. According to the calculation, the schematic of the positions of pockets F1, which are represented by orange spheres along the Γ−X direction of the BZ in Fig. 5e. The pockets along Γ−S are large and cannot be easily modified, hence for clarity they are not shown here and the Fermi pockets are plotted in Supplementary Fig. 9. Instead, the bands along Γ−X are shallow and host Weyl points and they should be susceptible to the magnetic field. The new F2 and F3 pockets appear after the disappearance of F1. So it is a reasonable assumption that they locate on the Γ−X line as well where the pockets F1 lie on, as shown in Fig. 5f. Indeed, some Weyl signatures were observed for the pockets F1. All the values extracted from the peak and valley positions of SdH oscillation fall on a line with an intercept of ~−0.01 in the Landau fan diagram, indicating a non-trivial π phase (see Supplementary Fig. 6b). Its cyclotron mass is a very small and changes with a magnetic field. Note that a normal parabolic band (\(E=\frac{\hslash {A}_{{\rm {F}}}}{2\pi m}\)) would not change its cyclotron mass (\({m}_{{\rm {CR}}}=\frac{{\hslash }^{2}}{2\pi }\frac{\partial {A}_{{\rm {F}}}(E,{k}_{\parallel })}{\partial E}\))43 as the Fermi energy changes. The increasing of the effective mass may imply the increase of spin fluctuation of the pockets with LT transition, similar to the early report14 instead of the response from a normal parabolic band. In order to better understand the Weyl nature of the Fermi pockets, it is indispensable for confirming the Weyl points along the direction of Γ−X line of the BZ. As shown in Fig. 5e, we obtained two pairs of Weyl points along the Γ−X line by band structure calculation of selected paths of the BZ and the details are listed in the table of Supplementary Fig. 11. The results agree with the prior work on Weyl points and Fermi surface of PrAlSi44.

Discussion

Take together, three prominent features of the LT in PrAlSi can be found: (i) the QO frequencies are strongly temperature dependent, (ii) the quasiparticle effective mass increases gradually when approaching B*, and (iii) the critical field for such LT is far below the quantum limit. In conventional metals, only a small change in QO frequency of the order of (kBT/EF)2 is expected upon warming45. Temperature-dependent QO frequency was observed in some HF metals, which is typically ascribed to the sensitivity of the f–c (c-conduction electrons) hybridization and the corresponding Kondo resonance state with a variation of temperature12,13,46. In this framework, the change of m* was also attributed to an itinerant-localized transition of 4f electrons14. However, in PrAlSi, DFT calculations manifested that the Pr-4f bands locate well below the Fermi level (see Supplementary Fig. 8), notable f–c hybridization is unlikely. Furthermore, PrAlSi is a low-carrier density semimetal, the Kondo screening is also expected to be weak according to Nozières exhaustion idea47,48. Therefore, it is unlikely that the observed LT in PrAlSi originates from a competition between the Zeeman term and a characteristic Kondo coherence energy as in HF systems. In the cases of bismuth21, TaP22, and TaAs23, the quantum limits have been reached to empty a Dirac or Weyl pocket and caused a field-induced LT. In our case, however, a rough estimate yields the quantum limit field in the range of 40–100 T, much larger than the critical field B* ~ 14.5 T.

Another possibility for the observed LT in PrAlSi might be related to the crystal-electric-field (CEF) effect. This arises because the nine-fold-degenerate j = 4 multiplet of Pr3+ in a D2d (\(\bar{4}\)2m) point symmetry CEF splits into two non-Kramers doublets and five singlets49. A recent analysis based on specific heat measurements revealed that the ground state is probably a doublet, while the magnetic entropy gain reaches \(R\ln 3\) at about 20 K, \(R\ln 4\) at about 30 K, and saturates to \(R\ln 9\) at a temperature as low as ~95 K24. This suggests that at least one excited state sitting not far above the ground doublet, potentially in the order of 10 K. It is reasonable to speculate that a magnetic field of ~ 10 T might be sufficient to modify the CEF energy levels and the orbital characters, which possibly changes the Fermi surface topology. In addition, this field-induced evolution of CEF levels is also qualitatively consistent with the temperature-dependent QO frequency and field-dependent m* as observed experimentally. Actually, this scenario was also proposed recently for the field-induced Fermi surface reconstruction in CeRhIn550. To further address this possibility, more experiments like inelastic neutron scattering are needed to figure out the diagram of the CEF splitting.

In summary, we grew high-quality single crystals and observed pronounced SdH oscillations in PrAlSi with a magnetic field up to 55 T. A LT transition occurs around 14.5 T. The change in carrier densities and Fermi pockets revealed by QO and the Hall effect are consistent with each other. By comparison with theoretical calculations, we propose that LT occurs along the Γ–X orientation and involves the Weyl pockets. One hole pocket becomes an electron pocket and a hole pocket, which indicates the existence of a van-Hove singularity. PrAlSi, therefore, represents a unique case of field-induced LT beyond the HF systems.

Methods

Sample growth and characterizations

Single crystals of PrAlSi used in our studies were synthesized using the flux method. The starting materials are high-purity chunks of praseodymium, silicon, and aluminum, mixed into an alumina crucible. Then, the alumina crucible and quartz wool were placed in a quartz tube, which was sealed under a high vacuum, and heated to 1100 °C at 3 °C/min. And holding for 12 h and then the tube was cooled down to 750 °C in 100 h and dwelt for 2 days. The excess Al flux was removed by centrifuging. Powder and single crystal x-ray diffraction (XRD) have been used to obtain the XRD pattern and confirm the structure and the orientation. The atomic proportion was determined by energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

Measurements

The low-field magnetic transport measurements were performed on an Integra AC (Oxford Instruments) with a 16 T superconducting magnet and a Leiden dilution refrigerator with a 14 T superconducting magnet. Temperature- and field-dependent resistivity measurements were made in the standard four-probe method with a pair of the current source (Keithley 6221) and DC-Nanovoltmeter (Keithley 2182A). The high-field magnetic transport measurements were carried out under a pulsed magnetic field at Wuhan National High Magnetic Field Center (WHMFC). Golden wires were attached using silver paste on the rectangular sample and every contact resistance was maintained to be <2 Ω in the measurements.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kamran Behina for insightful discussions. This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1403503), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12004123, 51861135104, and 11574097), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant no. 2019kfyXMBZ071), the open research fund of Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory (2022SLABFN27) and National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1602602).

Data availability

The data supporting the present work are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Lifshitz, I. Anomalies of electron characteristics of a metal in the high pressure region. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 1130–1135 (1960).

Varlamov, A. A., Galperin, Y. M., Sharapov, S. G. & Yerin, Y. Concise guide for electronic topological transitions. Low Temp. Phys. 47, 672–683 (2021).

Steppke, A. et al. Strong peak in Tc of Sr2RuO4 under uniaxial pressure. Science 355, 145 (2017).

Luo, Y. et al. Normal State 17O NMR Studies of Sr2RuO4 under Uniaxial Stress. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021044 (2019).

Yang, H. F. et al. Topological Lifshitz transitions and Fermi arc manipulation in Weyl semimetal NbAs. Nat. Commun. 10, 3478 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Bond-breaking induced Lifshitz transition in robust Dirac semimetal VAl3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 15517 (2020).

Benhabib, S. et al. Collapse of the normal-state pseudogap at a Lifshitz transition in the Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ cuprate superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 147001 (2015).

Norman, M. R., Lin, J. & Millis, A. J. Lifshitz transition in underdoped cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 81, 180513 (2010).

Ren, M. et al. Superconductivity across Lifshitz transition and anomalous insulating state in surface K-dosed (Li0.8Fe0.2OH)FeSe. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603238 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Evidence for a Lifshitz transition in electron-doped iron arsenic superconductors at the onset of superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 6, 419–423 (2010).

Kwon, J. et al. Lifshitz-transition-driven metal-insulator transition in moderately spin–orbit-coupled Sr2−xLaxRhO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 106401 (2019).

Kozlova, N. et al. Magnetic-field-induced band-structure change in CeBiPt. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 086403 (2005).

Aoki, D. et al. Field-induced Lifshitz transition without metamagnetism in CeIrIn5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 037202 (2016).

Aoki, H., Uji, S., Albessard, A. K. & Ōnuki, Y. Transition of f electron nature from itinerant to localized: Metamagnetic transition in CeRu2Si2 studied via the de Haas–van Alphen effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2110–2113 (1993).

Bastien, G. et al. Lifshitz transitions in the ferromagnetic superconductor UCoGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 206401 (2016).

Yelland, E. A., Barraclough, J. M., Wang, W., Kamenev, K. V. & Huxley, A. D. High-field superconductivity at an electronic topological transition in URhGe. Nat. Phys. 7, 890–894 (2011).

Niu, Q. et al. Fermi-surface instability in the heavy-fermion superconductor UTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 086601 (2020).

Pfau, H. et al. Interplay between Kondo suppression and Lifshitz transitions in YbRh2Si2 at high magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 256403 (2013).

Pfau, H. et al. Cascade of magnetic-field-induced Lifshitz transitions in the ferromagnetic Kondo lattice material YbNi4P2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 126402 (2017).

Gourgout, A. et al. Collapse of ferromagnetism and Fermi surface instability near reentrant superconductivity of URhGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 046401 (2016).

Zhu, Z. et al. Emptying Dirac valleys in bismuth using high magnetic fields. Nat. Commun. 8, 15297 (2017).

Zhang, C.-L. et al. Magnetic-tunnelling-induced Weyl node annihilation in TaP. Nat. Phys. 13, 979–986 (2017).

Ramshaw, B. J. et al. Quantum limit transport and destruction of the Weyl nodes in TaAs. Nat. Commun. 9, 2217 (2018).

Lyu, M. et al. Nonsaturating magnetoresistance, anomalous Hall effect, and magnetic quantum oscillations in the ferromagnetic semimetal PrAlSi. Phys. Rev. B 102, 085143 (2020).

Chang, G. et al. Magnetic and noncentrosymmetric Weyl fermion semimetals in the RAlGe family of compounds (R = rare earth). Phys. Rev. B 97, 041104 (2018).

Puphal, P. et al. Bulk single-crystal growth of the theoretically predicted magnetic Weyl semimetals RAlGe (R = Pr, Ce). Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 024204 (2019).

Nakatsuji, S., Kiyohara, N. & Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 527, 212–215 (2015).

Kuroda, K. et al. Evidence for magnetic Weyl fermions in a correlated metal. Nat. Mater. 16, 1090–1095 (2017).

Liu, E. et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125–1131 (2018).

Morali, N. et al. Fermi-arc diversity on surface terminations of the magnetic Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2. Science 365, 1286–1291 (2019).

Sakai, A. et al. Giant anomalous Nernst effect and quantum-critical scaling in a ferromagnetic semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1119–1124 (2018).

Su, H. et al. Multiple Weyl fermions in the noncentrosymmetric semimetal LaAlSi. Phys. Rev. B 103, 165128 (2021).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Discovery of Lorentz-violating type II Weyl fermions in LaAlGe. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603266 (2017).

Puphal, P. et al. Topological magnetic phase in the candidate Weyl semimetal CeAlGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 017202 (2020).

Yang, H.-Y. et al. Noncollinear ferromagnetic Weyl semimetal with anisotropic anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 103, 115143 (2021).

Gaudet, J. et al. Weyl-mediated helical magnetism in NdAlSi. Nat. Mater. 20, 1650–1656 (2021).

Ding, L. et al. Intrinsic anomalous Nernst effect amplified by disorder in a half-metallic semimetal. Phys. Rev. X 9, 041061 (2019).

Fauqué, B. et al. Magnetoresistance of semimetals: the case of antimony. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 114201 (2018).

Bhargava, R. N. de Haas–van Alphen and galvanomagnetic effect in Bi and Bi–Pb alloys. Phys. Rev. 156, 785–797 (1967).

Zhu, Z. et al. Quantum oscillations, thermoelectric coefficients, and the fermi surface of semimetallic WTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 176601 (2015).

Luttinger, J. M. Fermi surface and some simple equilibrium properties of a system of interacting fermions. Phys. Rev. 119, 1153–1163 (1960).

Julian, S. Numerical extraction of de Haas–van Alphen frequencies from calculated band energies. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 324–332 (2012).

Singleton, J. Band Theory and Electronic Properties of Solids, Vol. 2 (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Yang, H.-Y. et al. Transition from intrinsic to extrinsic anomalous Hall effect in the ferromagnetic Weyl semimetal PrAlGe1−xSix. APL Mater. 8, 011111 (2020).

Shoenberg, D. Magnetic Oscillations in Metals (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Goll, G. et al. Temperature-dependent fermi surface in CeBiPt. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 57, 233 (2002).

Nozières, P. Some comments on Kondo lattices and the Mott transition. Eur. Phys. J. B 6, 447–457 (1998).

He, X. et al. PrBi: topology meets quadrupolar degrees of freedom. Phys. Rev. B 101, 075106 (2020).

Dhar, S. The heat capacity of PrSi2. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 132, 149–152 (1994).

Lesseux, G. G. et al. Orbitally defined field-induced electronic state in a Kondo lattice. Phys. Rev. B 101, 165111 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and L.Z. conceived and oversaw this work. L.W., H.Z., and L.Z. performed the experiments. Z.Z., G.X., L.W., and S.C. performed band structure calculations. L.W., L.Z., Y.L., and Z.Z. wrote the manuscript with inputs from co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Chi, S., Zuo, H. et al. Field-induced Lifshitz transition in the magnetic Weyl semimetal candidate PrAlSi. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 4 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-023-00537-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-023-00537-y

This article is cited by

-

Weyl metallic state induced by helical magnetic order

npj Quantum Materials (2024)

-

Emergence of Weyl fermions by ferrimagnetism in a noncentrosymmetric magnetic Weyl semimetal

Nature Communications (2023)