Abstract

Nontrivial band topologies in semimetals lead to robust surface states that can contribute dominantly to the total conduction. This may result in reduced resistivity with decreasing feature size contrary to conventional metals, which may highly impact the semiconductor industry. Here we study the resistivity scaling of a representative topological semimetal CoSi using realistic band structures and Green’s function methods. We show that there exists a critical thickness dc dividing different scaling trends. Above dc, when the defect density is low such that surface conduction dominates, resistivity reduces with decreasing thickness; when the defect density is high such that bulk conduction dominates, resistivity increases as in conventional metals. Below dc where bulk states are depopulated, the persistent Fermi-arc remnant states give rise to decreasing resistivity down to the ultrathin limit, unlike topological insulators. The observed CoSi scaling can apply to broad classes of topological semimetals, providing guidelines for materials screening in back-end-of-line interconnect applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

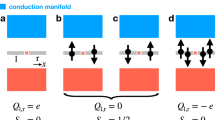

Topological semimetals comprise unconventional materials in which the conduction and valence bands touch at discrete pairs of nodal points or form close-loop nodal lines in the Brillouin zone near the Fermi level1,2,3,4. The nontrivial bulk-band topology near the band-crossings yields robust surface states that connect between the nodes, forming open Fermi arcs. Both surface and bulk states contribute to rich transport properties5,6,7. In the simplest Weyl semimetal comprising two Weyl nodes, carrier transport via the Fermi-arc states resembles that of the edge-states in a stack of 2D quantum anomalous Hall insulators8, yielding size-independent contributions to total conductivity at macroscopic scales9. In a nonmagnetic Weyl semimetal, if the relaxation lengths associated with the scattering processes between time-reversed partners exceed the sample thickness, similar quantum Hall physics would hold, as if there were two independent Fermi-arc conduction channels9.

Furthermore, the increasing surface-to-bulk ratio with reduced sample dimensions should lead to decreased resistivity due to Fermi-arc transport10. Indeed, measurements of NbAs and CoSi appear to support this conjecture: resistivity of ~100 nm thick NbAs nanobelts drops ≥10-fold below its bulk value to ~1 μΩ cm11 (lower than bulk Cu resistivity), while that of CoSi nanowires decreases with reduced diameters to ≤1/5 of its bulk value12. This differs markedly from conventional metals (e.g., Cu) whose resistivity increases with reduced dimensions due to carrier scattering off surfaces, grain-boundaries, and so on13. The increase in wiring resistance has become a major challenge for advanced semiconductor technologies. In comparison, the resistivity reduction in nanoscale NbAs and CoSi may yield significant performance gains14,15. For example, if the low resistivity observed in the NbAs nanobelts11 can persist down to the nanometer scale and can be observed in a wider class of materials compatible with silicon technologies, then replacing copper with topological semimetals for wiring up the transistors can improve the power-performance of integrated circuits by at least 10% to ~40%, equivalent to 1 to 4 technology-node generations of performance gain14, promoting topological semimetals for beyond Cu interconnects among other applications15,16,17,18. It is thus imperative to understand the underlying physics and generality of such a resistivity scaling for a broad class of topological semimetals. To this end, we report a rigorous study using a combined first-principles and analytical modeling approach for a representative topological semimetal, the chiral multifermion semimetal CoSi, a material that can be readily integrated in the silicon technology. Our work elucidates the various resistivity scaling regimes in thin films with thickness ranging from 2 to ~50 unit cells and reveals the conditions under which unconventional scaling reverts to conventional metallic scaling.

Results

Electronic structure of CoSi

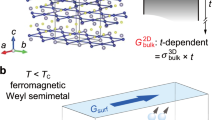

CoSi is nonmagnetic with a chiral cubic structure (space group # 198) that breaks the inversion symmetry (Fig. 1a). In the absence of spin–orbit coupling (SOC), density-functional theory (DFT) derived bulk band structure reveals a three-fold degenerate band-crossing at Γ and a four-fold degenerate band-crossing at R (Fig. 1c), with Chern numbers +2 and −2 respectively19,20. Consequently, two Fermi arcs (per spin) connect the \(\bar \Gamma\) and \(\bar R\) points, spanning the entire projected Brillouin Zone (BZ) along the (100) and equivalent surfaces (Fig. 1d), as confirmed by the angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy21,22,23. In the presence of SOC, each of the doubly degenerate Fermi arcs is split into two. The total number of Fermi arcs extending from near \(\bar \Gamma\) to near \(\bar R\) remains the same (4). Therefore, the surface-state contributions to transport would not change qualitatively. Experimentally, since the SOC induced energy splitting is smaller than other broadenings in the CoSi samples, ARPES cannot resolve the Fermi-arc splitting21,22,23. Thus, within the experimental tolerance, the electronic states near the Fermi level are well described by a model without SOC.

a Unit cell of CoSi with lattice constants a = b = c = 4.438 Å. b Corresponding bulk Brillouin Zone (BZ) and its projection along the (100) surface (shown in red). c Bulk electronic band structure of CoSi. d Surface-state spectral weight (in red) of a (100)-oriented semi-infinite CoSi slab with the color scale in arbitrary unit. The blue area indicates the bulk bands projected on the (100) surface.

Resistance-area scaling in CoSi slabs with line defects

We first study the DFT informed quantum transport of electrons along the [001] direction in (100)-oriented CoSi slabs of varying thickness, using a 2-terminal device configuration (Fig. 2a) with and without line defects. The slab structure is finite along y and infinite along z, and the transport direction points along x. The line defect in the form of a surface notch extends from z = −∞ to z = +∞ while preserving translational symmetry along z. The self-consistent single-particle Kohn–Sham (KS) Hamiltonian HKS of the scattering region in Fig. 2a is evaluated using the QuantumATK package24. The total conductance per unit area is calculated using the Nonequilibrium Green’s Function (NEGF) technique25 (see “Methods” on ‘DFT-informed quantum transport calculation for CoSi slabs with 1D line defects’).

a Schematic view of a two-terminal device with a scattering region composed of a CoSi slab of thickness d along the [100] direction, sandwiched between two semi-infinite CoSi leads. An external bias-voltage \(V_{{{{\mathrm{bias}}}}} \ll E_F/{{{e}}}\) (with e the electron’s charge) injects a charge current in the [001] direction. The arrows illustrate the surface current distribution on the top surface in the presence of defects (shown as a notch). b Fermi surface of a 40AL CoSi slab with d = 36.05 Å. Fermi-arc surface states on the top and bottom surfaces are denoted in red and blue solid lines, respectively. The dashed lines indicate the topologically trivial surface states, while the gray lines indicate the bulk states. c Top panel: band structure of the same slab along the linecut L1 in b at \(k_z = 0.52\left( {{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a} \right) \equiv k_{z1}\), revealing the Fermi-arc surface states (in blue and red) connecting between the bulk valence and conduction bands (in gray). The markers S1 and S2 in b and c indicate the conducting channels available for transport at a fixed \(k_{z1}\). Bottom panel: band structure of the slab along the linecut L2 in b at \(k_z = 0.3\left( {{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a} \right) \equiv k_{z2}\). The markers Si (i = 3 to 8) indicate the conducting channels available for transport at \(k_{z2}\). d, \(k_z\)-resolved transmission \(T\left( {k_z} \right)\) for a pristine 40 AL CoSi slab, compared to that for a slab with a notch on the top surface. e Thickness dependence of the resistance-area (RA) product of Cu and CoSi slabs, normalized by the RA product in the infinite thickness limit, denoted as (RA)bulk. The orange curves represent pristine slabs, while the black curves represent slabs with surface disorder in the form of a notch on the top surface. We note that (RA)slab/(RA)bulk is equivalent to the normalized resistivity (\(\rho /\rho _0\)) as the channel length is fixed in the simulations of the same material.

Figure 2b depicts the Fermi surface of a 40 atomic-layer (AL) CoSi slab (thickness d = 36.05 Å), showing that conduction at the Fermi level EF predominantly comes from the Fermi arcs (denoted by red and blue lines) permeating throughout the projected BZ, while the bulk states (in gray) concentrate near [0, 0] and [π, π]. Correspondingly, the local density of states (LDOS) near the surfaces is significantly higher than the LDOS in the bulk (Supplementary Fig. 2a), and the thinner the slab, the larger the surface- to total-current ratio (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Furthermore, the band structure along a linecut (e.g., L1 along \(k_z = 0.52{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\)) in the 2D BZ shows that the left- and right-moving Fermi-arc states (S1 and S2) reside on opposite surfaces (see top panel of Fig. 2c), resembling the chiral edge states in quantum Hall insulators. Consequently, in CoSi slabs with line defects that preserve the translational invariance along z, if the slab is thick enough such that the top and bottom surface states do not overlap, backscattering between them is negligible. This is confirmed in the k-resolved transmission \(T(k_z)\) (Fig. 2d), where the transmission remains intact between \(k_z\sim 0.4{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\) and \(\sim\!\!0.7{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\) despite the surface defect.

Between \(k_z\sim 0.2{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\) and \(\sim\!\! 0.4{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\), multiple Fermi-arc states participate in transport while the bulk conduction is negligible. At a fixed \(k_z\), only an odd number of surface states exist per surface per spin. For example, along \(k_z = 0.3{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\) (L2 in Fig. 2b), there are three states on the top (S3, S5, and S7) and bottom (S4, S6, and S8) surfaces, respectively. Just as S1 and S2, the states related by a C2 rotation along the z-axis (e.g., S4 and S7) are located on opposite surfaces and cannot backscatter among each other. Nevertheless, S4 can backscatter to S8. Therefore, scattering off a line defect does reduce T (e.g., from 3 to ~2 at \(k_z = 0.3{{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}/a\)), but \(T(k_z)\) remains larger than one because band topology guarantees an extra forward-moving surface mode for transport. This protected Fermi-arc transmission can be seen in CoSi slabs with various types of line defects (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 2e shows how the Fermi-arc states impact the scaling of resistance-area (RA) product. The number of Fermi-arc channels remains nearly constant with decreasing film thickness, and, at the nanoscale, surface conduction dominates over bulk conduction. Thus, when thickness is reduced, the conductance per unit cross-sectional area increases, i.e., the slab RA decreases to well below the bulk RA (see the orange curve with filled circles). This sharply contrasts the scaling in conventional metals, e.g., Cu, where the bulk states carry the conduction and therefore (RA)slab/(RA)bulk ~ 1 in pristine films even at nanoscale (orange curve with open circles). The contrast is even more drastic when there is disorder: scattering of bulk carriers off surface defects in Cu yields an increasing RA with reduced thickness (black curve with open circles), while the protected transmission of Fermi-arc carriers in CoSi maintains the decreasing RA with reduced thickness (black curve with filled circles) despite some loss in transmission. We note that, in the presence of SOC, the split Fermi arcs still extend from near \(\bar \Gamma\) to near \(\bar R\), spanning a large phase space in the BZ. Thus, surface-state transport still dominates. Furthermore, at a fixed \(k_z\), electrons of the split surface bands travel along the same direction, and the chiral edge-state like characteristic remains. Thus, the trend of decreasing RA with scaling holds regardless of SOC.

Translational invariance of the line defects ensures that electrons only scatter between the Fermi-arc surface states with the same kz (see Fig. 2b), resulting in a protected chiral Fermi-arc transport. However, in the presence of point defects, this is no longer true, and an enlarged phase space for scattering leads to a more complex scaling behavior.

Resistivity scaling in CoSi slabs with point defects

When there are point defects, the DFT-informed NEGF calculations become prohibitively expensive. Thus, we perform calculations within the tight-binding formalism by constructing Wannier functions that can reproduce the band structures generated by QuantumATK (see “Methods” on ‘Model Hamiltonians of CoSi bulk, slabs, and vacancies’). This method enables us to extend the relaxation length and conductivity calculations for CoSi films from a few unit-cell to over 100-unit-cell thick. Furthermore, instead of using wave functions explicitly in the Fermi golden rule and Kubo’s formula26,27, we adopt Green’s functions in the computation in the matrix form (see “Methods” on ‘Relaxation length calculations by the Fermi golden rule’ and ‘Conductivity calculations by Kubo’s formula’), which accounts for all matrix-element effects, including suppression of transitions between opposite (pseudo-)spins. This approach speeds up the convergence. It also allows us to introduce an energy broadening factor η (~1 meV) as the simplest model for other scattering sources that reduce the lifetime of the entire system uniformly. Next, we introduce Co vacancies on the film surface (Fig. 3a) and construct the corresponding impurity potential and T-matrix (see “Methods” on ‘T-matrix calculation’). Cobalt vacancies are used to model the surface defects because their formation energy is lower than Si vacancies. We focus on the impact of surface defects instead of bulk defects because Fermi-arc states dominate the transport of pristine CoSi thin films (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Crystal structure of a CoSi slab. A yellow cross indicates the position of a surface vacancy point defect. b Longitudinal resistivity \(\rho\) as a function of the slab thickness, calculated from first-principles electronic structure and Kubo’s formula, for different surface defect density N (\(N = 0.01\) is equivalent to areal density \(\sim\!\! 5 \times 10^{12}\,{{{\mathrm{cm}}}}^{ - 2}\)). In region I, well-differentiated surface and bulk states coexist at the Fermi level. In region II, only remnants of the surface states are present at the Fermi level. The resistivity in the infinite thickness limit is denoted as \(\rho _0\). c Longitudinal resistivity \(\rho\) as a function of the slab thickness in region I, calculated from a combined analytical and first-principles approach (see Supplementary Discussion), for different surface defect density N.

Figure 3b, c summarize the key results of this work: resistivity scaling of CoSi with film thickness (\(\rho /\rho _0\) vs. d) and surface defect density N (defined as the number of defects per unit cell of the slab), where \(\rho _0\) denotes the resistivity of an infinite bulk (see “Methods” on ‘Simulation of resistivity vs. thickness scaling’). We observe that, when N is small, \(\rho /\rho _0\) decreases with decreasing thickness d, consistent with the RA scaling in slabs with a shallow notch (Fig. 2e). When N is large, resistivity scales differently above (region I) and below (region II) a “critical” thickness dc of 6 unit cells (denoted by the dashed line). Next, we explain this scaling behavior with an analytical model.

Resistivity scaling above the critical thickness

When \(d \,>\, d_c\), well-differentiated surface and bulk channels conduct in parallel and hence \(\rho /\rho _0 = \sigma _0/\left( {\sigma _b + \sigma _s} \right),\) where \(\sigma _0 = 1/\rho _0\) is the conductivity of an infinite bulk and \(\sigma _s\) (\(\sigma _b\)) is the average contribution from surface (bulk) states to the 3D total conductivity of the film9. In this regime, the d-dependence of \(\rho\) follows from the competition between two opposite trends.

On the one hand, \(\sigma _s\) grows as d decreases because the number of Fermi-arcs is independent of d. Hence, for thinner samples, Fermi arcs make a higher average contribution to the 3D conductivity. Specifically, an analytical theory developed in Supplementary Discussion shows that

where \(k_0 = \sqrt 2 {{{\mathrm{\pi }}}}\)/a is the effective length of the Fermi arcs and \(l_s\) is an effective relaxation length for surface electrons. Above dc, ls hardly varies with d (Supplementary Fig. 4), which can be understood by a dimensional analysis argument (see Supplementary Discussion on “Scaling of relaxation lengths with impurity concentration and system size”). Therefore, \(\sigma _s\) scales roughly with \(d^{ - 1}\).

On the other hand, \(\sigma _b\) decreases as d decreases (Fig. 4a). Since the 3D bulk mean free path \(l_0\) and the bulk density of states in region I are approximately independent of d (see Supplementary Discussion on “Scaling of relaxation lengths with impurity concentration and system size” and Supplementary Fig. 5), the observed behavior can be attributed to the Fuchs–Sondheimer (FS) mechanism28, namely, the diffusive scattering of bulk electrons from the surfaces. Indeed, the calculated \(\sigma _b\) vs d curves fit well to the FS theory (see Fig. 4b and “Methods” on ‘Fitting to Fuchs–Sondheimer model’).

a Pure bulk conductivity \(\sigma _b\) (not including the surface state contribution) as a function of slab thickness, for different surface defect density N \(\left( {N = 0.01\,{{{\mathrm{is}}}}\,{{{\mathrm{equivalent}}}}\,{{{\mathrm{to}}}}\,{{{\mathrm{areal}}}}\,{{{\mathrm{density}}}}\sim\!\! 5 \times 10^{12}\,{{{\mathrm{cm}}}}^{ - 2}} \right)\). The range of thickness considered corresponds to region I of Fig. 3. b Inverse ratio of the bulk conductivity \(\sigma _b\) to the infinite thickness conductivity \(\sigma _0\). The numerical data are fit to the Fuchs–Sondheimer model. The probability of specular surface scattering, p, decreases as N increases.

Which of these two competing trends dominates in the overall resistivity scaling depends on the \(\sigma _s/\sigma _b\) ratio. Combining Eq. (1) with the FS theory for \(\sigma _b\), we have

for \(l_0 \gg d\), where \(k_F \ll 1/a\) is the maximal Fermi wave vector of the bulk crystal for the dominant Fermi pocket. Thus, the main factors enhancing the relative contribution of the surface states to the average 3D conductivity include: (i) long Fermi arcs (\(k_0 \gg k_F\)), (ii) long surface relaxation lengths (\(l_s \gg d\)), and (iii) small film thickness (\(d \,\lesssim\, k_F^{ - 1}\)). When \(N = 0\), we find \(\sigma _s/{{{\mathrm{\sigma }}}}_b \gtrsim 1\) for the range of d studied (Supplementary Fig. 6), mainly due to \(k_0 \gg k_F\) and \(l_s \gg d\). In this case, the surface contribution is dominant. Therefore \(\rho /\rho _0\) decreases as d decreases. As N increases, the reduction of \(l_s\) and \(l_0\) results in a decrease of σs/σb (see Eq. (2) and Supplementary Fig. 6). For sufficiently large N, σs/σb drops appreciably below unity, and the bulk contribution becomes dominant, resulting in the sign change of the slope of \(\rho /\rho _0\) vs d (Fig. 3b, c).

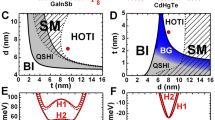

Resistivity scaling in the ultrathin limit

When d < dc, according to Fig. 5, all bulk sub-bands are depopulated. The only states present at the Fermi level are the remnant of Fermi arcs whose wave functions now spread throughout the entire film volume. We note that, contrary to topological insulators, e.g., Bi2Se3, in which the Dirac-cone surface states become gapped in the ultrathin limit due to top-bottom surface hybridization, most of the Fermi-arc states in CoSi remain conducting. This is because, owing to the top-bottom surface asymmetry associated with the CoSi chiral crystalline structure, the majority of the Fermi-arc states from the opposite surfaces do not overlap in the k-space, which protects them from the hybridization-induced gap opening.

a–c Band structures near \(\bar R\), for slab thicknesses of 4 unit cells (u. c.), 6 u. c. and 8 u. c. (respectively). The arrows show the evolution of the bottom of the bulk sub-bands near the Fermi level with decreasing thickness. At the critical thickness of 6 u. c., the bottom of a bulk sub-band crosses the Fermi level, giving rise to a van Hove singularity in the density of states at the Fermi level. Below 6 u. c., the only bands left at the Fermi level are the remnant of the Fermi-arc states. d–i Electronic spectral functions of the top 2 layers (\(A_k^{{{{\mathrm{top}}}}}\)) and bottom 2 layers (\(A_k^{{{{\mathrm{bot}}}}}\)) in 4 u. c., 6 u. c., and 8 u. c CoSi slabs with the color scale in arbitrary unit. The two spectral functions are related by a C2 rotation. In the thinnest samples, the Fermi-arc remnant states are spread rather uniformly over the entire film volume, thereby yielding \(A_k^{{{{\mathrm{top}}}}} \simeq A_k^{{{{\mathrm{bot}}}}}\). The red circles in d–f indicate the splitting of Fermi arcs due to top and bottom surface hybridization. The thinner the slab, the larger the splitting.

For these Fermi-arc remnant states, the 3D conductivity roughly scales as \(\sigma \propto \tau /d\), where τ is a scattering time and the 1/d factor originates from the fact that the number of remnant Fermi-arc states does not vary appreciably with the film thickness. From Matthiessen’s rule, the scattering rate is a sum of the rates due to surface vacancies and other sources, i.e., \(\tau ^{ - 1} \sim a\,n_{{{{\mathrm{imp}}}}} + b\,\eta\), where \(n_{{{{\mathrm{imp}}}}} = N/d\) is the volume impurity density and a, b are approximately constant. Accordingly, \(\rho /\rho _0 = \sigma _0/\sigma \propto a\,N + b\,d\,\eta\) is roughly a linear function of d, with an intercept proportional to N and a slope independent of N. This simple functional form fits qualitatively well to the numerical results in region II of Fig. 3b (see Supplementary Fig. 7). In summary, the Fermi-arc contribution to the 3D conductivity remains remarkably robust down to the thinnest films and thereby enables a favorable resistivity scaling. Similar physics is also observed in the RA scaling of CoSi films with line defects (see Fig. 2e).

Resistivity at the critical thickness

There are two noticeable features in Fig. 3b associated with d = dc. First, in films with a large N, the slope of \(\rho /\rho _0\) vs. d reverses when crossing over from above to below dc, prompted by the conversion from the bulk sub-band dominated transport to Fermi-arc remnant dominated transport as explained in the preceding discussion. Second, there is a resistivity kink at dc because at d = dc, the bulk conduction band around R starts to emerge at the Fermi level, giving rise to a van Hove singularity (Fig. 5a–c).

On one hand, the van Hove singularity contributes to more conduction channels, which would increase the total conductivity. On the other hand, the appearance of bulk states at the Fermi level reduces the lifetime for the remnants of the Fermi-arc states, which would decrease the total conductivity. Since the contribution from the emerging bulk states to conductivity is still small at \(d \simeq d_c\) (the group velocity of the bulk states at the Fermi level being particularly small at \(d = d_c\)), the increased phase space for scattering is the dominant factor and gives rise to an upward kink in resistivity at dc.

According to this interpretation, dc is generally determined by the thickness below which the bulk sub-bands are completely depopulated and only the Fermi-arc remnant states persist. This phenomenon is not unique to CoSi, and it would be interesting to validate it in other topological semimetals. We expect the exact values of dc to depend on the specific materials and the chemical potential of a specific sample. There may also be multiple dc values if a material has two or more bulk-band valleys near the Fermi level that contribute strongly to transport.

Last, we note that the surface-state penetration depth and the relaxation length associated with the top-bottom surface scattering (\(l_{tb}\)) are not directly relevant to dc. While dc is fixed for a specific material system, the surface penetration depth varies with the wavevector k. Also, as shown in Fig. 5, the spreading of the surface-state wavefunction at each k-point toward the opposite surface evolves smoothly across dc, but the resistivity scaling trend changes abruptly across dc (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, dc is a material-specific quantity determined by the electronic bandstructure and Fermi level, independent of the surface defect density N and film thickness d. In contrast, \(l_{\rm{tb}}\) depends on N and d among other factors, and it is several orders of magnitude larger than dc for the range of N investigated here. These observations corroborate our interpretation that the van Hove singularity associated the emergent bulk sub-band plays a dominant role in determining dc, as opposed to the spreading of the Fermi-arc surface-state wavefunctions and \(l_{\rm{tb}}.\)

Discussion

We conclude with a discussion on the resistivity scaling of general topological semimetals, focusing on materials with well-separated bulk and Fermi-arc surfaces states. First, we note the similarities and the differences between the \(\rho\) vs. d scaling of the chiral CoSi in Fig. 3b and that of the Weyl semimetal toy model in Fig. 4 of ref. 9. In symmetry-protected multifermion semimetals29, such as CoSi, each Weyl node is its own time-reversed partner. Thus, the pair of time-reversed subsystems are strongly coupled. Consequently, instead of a two-step drop in resistivity with a plateau in between that manifests the two channels of anomalous Hall current of the two decoupled time-reversed subsystems in nonmagnetic Weyl semimetals9, we see a one-step resistivity drop caused by the dominance of surface conduction over bulk conduction with scaling.

In short, in clean samples with low defect densities N and thicknesses above dc, the monotonically decreasing resistivity in CoSi is a general feature for nonmagnetic topological semimetals with strongly coupled time-reversed partners, such as chiral multifermion semimetals19,20,21,22,23 and Dirac semimetals with Fermi arcs30,31. It is also a general feature for magnetic Weyl semimetals with broken time-reversal symmetry32,33,34. In contrast, the two-step resistivity decrease shown in ref. 9 is a general feature for nonmagnetic topological semimetals with well separated time-reversed subsystems, such as TaAs35,36.

On the other hand, in samples with high N and thicknesses above dc, the increased resistivity with scaling due to the FS mechanism is a universal feature for most topological semimetals. This is broadly applicable to materials in which the bulk conduction dominates over surface conduction (\(\sigma _b/{{{\mathrm{\sigma }}}}_s \,>\, 1\)), as in conventional metals.

Below dc, where the surface-bulk separation is no longer valid, the decreased resistivity with scaling in CoSi regardless of N is a general feature for topological semimetals with conducting surface states down to the ultrathin limit (see Supplementary Fig. 8), in sharp contrast to prototypical topological insulators, such as Bi2Se3, where the topological surface states are gapped out. This property is highly desirable for nanometer-scale interconnects and can be found in topological materials with a sufficiently small overlap between the top- and bottom-surface Fermi arcs in the BZ. Examples include topological semimetals with chiral crystalline structures (e.g., CoSi, RhSi, etc.)19,20,37 and Weyl semimetals with asymmetric top and bottom surface terminations, comprising different types of atoms (e.g., TaAs, NbAs)35,36,38,39,40.

Besides the small coupling between the asymmetric top- and bottom-surface Fermi arcs, other desirable properties that can promote surface conduction include long Fermi arcs (e.g., CoSi, RhSi, AlPt, etc.)21,22,23,37, many well-separated Weyl nodes, well-separated time-reversed surface-state partners to enhance the surface relaxation lengths (e.g., TaAs), and conduction via chiral-edge-state like Fermi arcs where carriers traveling in opposite directions locate on opposite surfaces to suppress backscattering (e.g., magnetic Weyl semimetals). These serve as the guiding principles for screening topological interconnect materials. Whether or not the abovementioned factors can be satisfied simultaneously is a direction for further research. Detailed analyses of the electron-phonon scattering41,42,43 on resistivity scaling in nanoscale topological semimetals would also be highly valuable.

Methods

DFT-informed quantum transport calculation for CoSi slabs with 1D line defects

The self-consistent single-particle KS Hamiltonian HKS of the scattering region in Fig. 2a is evaluated using Synopsys’ QuantumATK package, where we employ double-zeta polarized localized orbitals as the basis set and the Perdew-Burke-Enzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation for the exchange correlation function as introduced in Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). The slab structures have a finite thickness along the y-direction and periodic boundary conditions in the x–z-plane with a 9 × 9 k-point grid that has been checked for convergence. In addition, all structures have been relaxed such that the force on every atom is less that 5 meV/Å.

The zero-temperature total conductance per unit width (G) of the scattering region in Fig. 2a in the zero-bias limit (\({{{\mathrm{e}}}}V_{{{{\mathrm{bias}}}}} \ll E_F\)) can be calculated using the NEGF technique:

where \(G_0 = 2{{{e}}}^2/h\) is the conductance quantum and \(T\left( {k_z,E} \right) = Tr\left( {G^r{{\Gamma }}_LG^a{{\Gamma }}_R} \right)\) is the kz-resolved transmission. Here, \(G^r\left( {k_z,E} \right) = \left[ {E + {{{\mathrm{i}}}}\eta - H_{{{{\mathrm{KS}}}}}\left( {k_z} \right) - \Sigma \left( {k_z,E} \right)} \right]^{ - 1} = \left[ {G^a\left( {k_z,E} \right)} \right]^{\dagger}\) is the retarded Green’s function, \(\Sigma \left( {k_z,E} \right)\) is the self-energy matrix of the left (L) and right (R) leads shown in Fig. 2a, and \(G^a\left( {k_z,E} \right)\) is the advanced Green’s function. Lastly, \({{\Gamma }}_\alpha = {{{\mathrm{i}}}}\left( {{{\Sigma }}_\alpha - {{\Sigma }}_\alpha ^{\dagger} } \right)\) is the level-broadening matrix of lead-α (\(\alpha = {{{\mathrm{L}}}},{{{\mathrm{R}}}}\)).

Model Hamiltonians of CoSi bulk, slabs, and vacancies

The Wannier-type Hamiltonian within the tight-binding (TB) formalism of the CoSi pristine bulk system is derived from the first-principles calculations using the Synopsys QuantumATK package with the d-orbitals of Co and p-orbitals of Si atoms, respectively. In Fig. 1d, we calculate the spectral weight of the surface and bulk states of a semi-infinite bulk using the iterative Green’s function, based on the method of cyclic reduction of block-tridiagonal matrices introduced in Phys. Rev. B 31, 5166 (1985).

The CoSi slab models with finite thickness d are built with the TB Hamiltonians truncated in the real space along the thickness direction (y). The Co vacancies on the top and bottom surface (Fig. 3a) are modeled by adding an impurity potential V that removes all hopping terms of the Hamiltonian to and from the vacancy sites and setting the on-site energy of the fictitious vacancy atoms to \(U_0\). The value of \(U_0\) determines the energy of the impurity level, which is unphysical for vacancies. We set \(U_0 = 10\) eV above the Fermi level and find that such a high-energy spurious impurity level has negligible effect on the resistivity scaling, as resistivity reflects only the low-energy physics near the Fermi level.

Note that since we consider non-magnetic defects and ignore the SOC, intermixing between spin-up and spin-down electrons is forbidden. When SOC is included, scattering between opposite pseudo-spins would similarly be suppressed. Thus, we expect the resistivity scaling to follow qualitatively the same trend as shown in Fig. 3b.

T-matrix calculation

The impurity potential in momentum space \(V_{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\) can be obtained by the Fourier transform of the impurity potential in real space. By summing up all diagrams involving multiple scatterings off the impurity, the total scattering matrix \(T\left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}},{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime } \right)\) can be formulated as,

where \(N_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime \left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^{\prime\prime }} \right)}\) is the total number of \({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime \left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^{\prime\prime }} \right)\) points; \(G_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime \left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^{\prime\prime }} \right)}^0\left( E \right)\) is the unfolded bare Green’s function at \({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime \left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^{\prime\prime }} \right)\) point for a given energy E. In this work, when T-matrix is involved, the sum over the momentum space goes up to the second Brillouin zone. Inclusion of the third zone has been tested in a few cases, and less than 10% difference is found.

Relaxation length calculations by the Fermi golden rule

In the Supplementary Discussion, we derive the Fermi golden rule expressions for the relaxation lengths (see Eqs. (28) and (29) in Supplementary Discussion). For first-principles calculations, it is advantageous to use the Green’s function instead of wave functions. As a result, Eq. (29) in Supplementary Discussion can be rewritten as

where “Im” stands for the imaginary part,

a is the lattice constant, \(N_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime } \right)}\) is the total number of \({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\left( {{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}^\prime } \right)\) points in the summation, N is the number of defects per unit cell of the slab, and the indices of \(s,\bar s\) in Eq. (5) (or s, b in Eq. (6)) denote the mean relaxation length between time-reversed surface states (or between surface and bulk states). The separation of the surface and bulk regions in the Brillouin zone is described in the next section. Last, in Eqs. (5) and (6), the trace Tr is taken over the electronic orbitals in the Hamiltonian matrix.

Separation of surface and bulk states

Because the bulk states can have nonzero spectral weights at the surface and the surface states can mix with the bulk states, in general, a rigorous separation between two cannot be done for finite slabs. Instead, we adopt a practical method to separate the surface and bulk states in the momentum space. The main concept is that any states that appear in the bulk energy gap region (which is forbidden under the 3D periodic condition) must involve surface terminations and have an exponentially decaying wave function amplitude in the bulk, and therefore, those states are defined as the surface states. At each in-plane \(\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\) point, we first identify the conduction-band minimum energy \(E_c\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\) and the valence-band maximum \(E_v\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\) of the three-dimensional (3D) CoSi bulk over all \(k_y\), where y is the out-of-plane direction. We then compute the eigen-energies for each \(\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\) of a two-dimensional (2D) CoSi slab, \(E_{2D}^n\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\), where n denotes the band index. If \(E_{2D}^n\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\) exists in the bulk band gap, i.e., \(E_v\left( {k_z,k_x} \right) \,<\, E_{2D}^n\left( {k_z,k_x} \right) \,<\, E_c\left( {k_z,k_x} \right)\), it is labeled as a surface state; otherwise, it is labeled as a bulk state. Since we only focus on the states near the Fermi level, our method divides the Brillouin zone into two regions: the surface states (inside the bulk band gap) and the bulk states, without any overlap. In some materials, there may exist surface resonances that intermix with the bulk bands. Nevertheless, in CoSi above the critical thickness, the effects of such surface resonances (if any) are negligible, as manifested by the constant density of the bulk states shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Conductivity calculations by Kubo’s formula

The electric conductivity of a 2D slab system can be computed by Kubo’s formula27:

where “Re” stands for the real part, the factor of two is the spin degeneracy, \(H_{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\) is the TB Hamiltonian of the CoSi slab, \(\frac{{\partial H}}{{\partial k_x}}\) is the x-direction velocity operator matrix, the trace is taken over the electronic orbitals of the Hamiltonian, and Gr(Ga) is the retarded (advanced) Green’s function,

Here, η ~ 1 meV is a constant that simulates the effect of scattering sources other than surface vacancies (e.g., bulk impurities, phonons, thermal broadening, etc.), and \({{\Sigma }}\left( {{{\boldsymbol{k}}}} \right)\) is the self-energy matrix:

where the real part of the self-energy matrix in Eq. (12) has been omitted, as it can be absorbed into the Fermi energy. The conductivity contributed by the bulk (surface) states, σb (σs), is derived from Eq. (9) by integrating over the bulk-state (surface-state) k-points. Note that the impurity vertex corrections are neglected in Eq. (9).

Simulation of resistivity vs. thickness scaling

We normalize the slab resistivity (ρ) against the 3D resistivity of an infinite bulk without vacancy (\(\rho _0\)) to obtain the relative resistivity,

Here \(\sigma ^{2{\rm{D}}}\) is the 2D conductivity of the slab model from Eq. (9); d is the thickness of the slab; \(\sigma _0\) is the 3D conductivity of the infinite bulk system and can be rewritten as:

where \(H_{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\) is the TB Hamiltonian of bulk CoSi.

3D bulk mean free path calculation

We calculate the near-equilibrium carrier transport to estimate the 3D bulk mean free path (l0). First, we obtain the ballistic conductance GB of the bulk CoSi system defined as

where \(G_0\) is the conductance quantum and

is the total transmission of the pristine bulk CoSi. In Eq. (16), the δ function is broadened to a Lorentzian of width 1 meV, to be consistent with the 3D infinite bulk conductivity (\(\sigma _0\)) obtained by Eq. (15). Here, the k-resolved transmission \(T\left( {k_y,k_z,E} \right)\) is calculated using the NEFG method (as discussed above for Eq. (3)) with a 300×300 k-grid-mesh over the Brillouin zone. Next, following the phenomenological expression

introduced in S. Datta’s “Lessons from Nanoelectronics: A New Perspective on Transport,” where \(\sigma ^B = G_Ba/A\) and A is the cross-sectional area of the unit cell used to calculate GB, we can obtain the 3D bulk mean free path as follows for fitting to the FS model in Fig. 4b:

Fitting to Fuchs–Sondheimer model

According to Fuchs–Sondheimer’s theory28, the ratio of the bulk resistivity \(\left( {1/\sigma _b} \right)\) of the film to that of the infinite bulk \(\left( {1/\sigma _0} \right)\) can be written as

where \(\kappa = d/l_0\), \(l_0\) is the 3D bulk mean free path calculated from Eq. (19), d is thickness of the film, p is the degree of specular reflection of the bulk electrons at the surface (\(0 \,<\, p \le 1\)). Given d and \(l_0\), we can obtain p by fitting to \(\frac{{{\it{\sigma }}_0}}{{{\it{\sigma }}_b\left( \kappa \right)}}\).

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Code availability

Code related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

References

Lv, B. Q., Qian, T. & Ding, H. Experimental perspective on three-dimensional topological semimetals. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025002 (2021).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Yan, B. & Felser, C. Topological materials: Weyl semimetals. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 8, 337–354 (2017).

Bansil, A., Lin, H. & Das, T. Colloquium: topological band theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 021004 (2016).

Hu, J., Xu, S.-Y., Ni, N. & Mao, Z. Transport of topological semimetals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 49, 207–252 (2019).

Wang, S., Lin, B.-C., Wang, A.-Q., Yu, D.-P. & Liao, Z.-M. Quantum transport in Dirac and Weyl semimetals: a review. Adv. Phys. X 2, 518–544 (2017).

Gorbar, E. V., Miransky, V. A., Shovkovy, I. A. & Sukhachov, P. O. Anomalous transport properties of Dirac and Weyl semimetals (Review Article). Low. Temp. Phys. 44, 487–505 (2018).

Burkov, A. A. & Balents, L. Weyl semimetal in a topological insulator multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127205 (2011).

Breitkreiz, M. & Brouwer, P. W. Large contribution of Fermi arcs to the conductivity of topological metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 066804 (2019).

Sukhachov, P. O., Rakov, M. V., Teslyk, O. M. & Gorbar, E. V. Fermi arcs and DC transport in nanowires of Dirac and Weyl semimetals. Ann. Phys. 532, 1900449 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Ultrahigh conductivity in Weyl semimetal NbAs nanobelts. Nat. Mater. 18, 482–488 (2019).

Tsai, C.-I. et al. Cobalt silicide nanostructures: synthesis, electron transport, and field emission properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 4514–4518 (2009).

Gall, D. The search for the most conductive metal for narrow interconnect lines. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 050901 (2020).

Chen, C.-T. et al. Topological semimetals for scaled back-end-of-line interconnect beyond Cu. In 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 32.4.1–32.4.4 (2020).

Gall, D. et al. Materials for interconnects. MRS Bull. 46, 959–966 (2021).

Wang, A.-Q., Ye, X.-G., Yu, D.-P. & Liao, Z.-M. Topological semimetal nanostructures: from properties to topotronics. ACS Nano 14, 3755–3778 (2020).

Liu, P., Williams, J. R. & Cha, J. J. Topological nanomaterials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 479–496 (2019).

Han, H. J., Liu, P. & Cha, J. J. 1D topological systems for next-generation electronics. Matter 4, 2596–2598 (2021).

Chang, G. et al. Unconventional chiral Fermions and large topological Fermi arcs in RhSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 206401 (2017).

Tang, P., Zhou, Q. & Zhang, S.-C. Multiple types of topological Fermions in transition metal silicides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 206402 (2017).

Sanchez, D. S. et al. Topological chiral crystals with helicoid-arc quantum states. Nature 567, 500–505 (2019).

Schröter, N. B. M. et al. Chiral topological semimetal with multifold band crossings and long Fermi arcs. Nat. Phys. 15, 759–765 (2019).

Takane, D. et al. Observation of chiral Fermions with a large topological charge and associated Fermi-arc surface states in CoSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 076402 (2019).

Atomistic Simulation Software | QuantumATK - Synopsys. https://www.synopsys.com/silicon/quantumatk.html.

Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Kubo, R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570–586 (1957).

Bruus, H. & Flensberg, K. Many-Body Quantum Theory in Condensed Matter Physics: An Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Sondheimer, E. H. The mean free path of electrons in metals. Adv. Phys. 1, 1–42 (1952).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Beyond Dirac and Weyl fermions: unconventional quasiparticles in conventional crystals. Science 353, aaf5037 (2016).

Wang, Z., Weng, H., Wu, Q., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetal and quantum transport in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125427 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Dirac semimetal and topological phase transitions in A3Bi (A = Na, K, Rb). Phys. Rev. B 85, 195320 (2012).

Belopolski, I. et al. Discovery of topological Weyl fermion lines and drumhead surface states in a room temperature magnet. Science 365, 1278–1281 (2019).

Liu, D. F. et al. Magnetic Weyl semimetal phase in a Kagomé crystal. Science 365, 1282–1285 (2019).

Morali, N. et al. Fermi-arc diversity on surface terminations of the magnetic Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2. Science 365, 1286–1291 (2019).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Observation of Weyl nodes in TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 724–727 (2015).

Yang, L. X. et al. Weyl semimetal phase in the non-centrosymmetric compound TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 728–732 (2015).

Chang, G. et al. Topological quantum properties of chiral crystals. Nat. Mater. 17, 978–985 (2018).

Souma, S. et al. Direct observation of nonequivalent Fermi-arc states of opposite surfaces in the noncentrosymmetric Weyl semimetal NbP. Phys. Rev. B 93, 161112 (2016).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Discovery of a Weyl fermion state with Fermi arcs in niobium arsenide. Nat. Phys. 11, 748–754 (2015).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Experimental discovery of a topological Weyl semimetal state in TaP. Sci. Adv. 1, e1501092 (2015).

Coulter, J. et al. Uncovering electron-phonon scattering and phonon dynamics in type-I Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 100, 220301 (2019).

Osterhoudt, G. B. et al. Evidence for dominant phonon-electron scattering in Weyl semimetal WP2. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011017 (2021).

Resta, G., Pi, S.-T., Wan, X. & Savrasov, S. Y. High surface conductivity of Fermi-arc electrons in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 97, 085142 (2018).

Acknowledgements

I.G. acknowledges financial support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Grant No. RGPIN- 2018- 05385), and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec Nature et Technologies. G.L. acknowledges the support under grant number MOE-2019-T2-2-215 and FRC-A-8000194-01-00. H.L. acknowledges the support from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) in Taiwan under grant number MOST 109-2112-M-001-014-MY3. The work at Northeastern University was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-20-1-0322 and it benefited from the computational resources of Northeastern University’s Advanced Scientific Computation Center (ASCC) and the Discovery Cluster. C.-T.C. acknowledges the fruitful discussions with R. Sundararaman, S. Kumar, J. Cha, C. Hinkle, and P. O. Sukhachov.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-T.C., H.L., and G.L. conceived the project. S.-W.L., C.-Y.H., C.-H.H., and Y.-H.T. performed the first-principles informed band structures, T-matrix, Green’s function, Fermi-golden rule calculations, and quantum transport calculations in consultation with H.L., G.L., T.-R.C., and A.B. I.G. developed the analytical modeling framework; U.B. performed the first-principles informed band structures and NEGF calculations for CoSi slabs in consultation with N.A.L. and H.L. I.G. and C.-T.C. performed the analyses and interpretation of the numerical results using the analytical framework, in consultation with H.L. and G.L. C.-T.C., I.G., S.-W.L., U.B., H.L., G.L., and Y.-H.T. wrote the manuscript. S.-W.L. and I.G. are co-first authors. All authors commented on the manuscript. C.-T.C. oversaw the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lien, SW., Garate, I., Bajpai, U. et al. Unconventional resistivity scaling in topological semimetal CoSi. npj Quantum Mater. 8, 3 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-022-00535-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-022-00535-6

This article is cited by

-

Topology stabilized fluctuations in a magnetic nodal semimetal

Nature Communications (2023)