Abstract

Hybrid structures of semiconducting (SM) nanowires, epitaxially grown superconductors (SC), and ferromagnetic-insulator (FI) layers have been explored experimentally and theoretically as alternative platforms for topological superconductivity at zero magnetic field. Here, we analyze a tripartite SM/FI/SC heterostructure but realized in a planar stacking geometry, where the thin FI layer acts as a spin-polarized barrier between the SM and the SC. We optimize the system’s geometrical parameters using microscopic simulations, finding the range of FI thicknesses for which the hybrid system can be tuned into the topological regime. Within this range, and thanks to the vertical confinement provided by the stacking geometry, trivial and topological phases alternate regularly as the external gate is varied, displaying a hard topological gap that can reach half of the SC one. This is a significant improvement compared to setups using hexagonal nanowires, which show erratic topological regions with typically smaller and softer gaps. Our proposal provides a magnetic field-free planar design for quasi-one-dimensional topological superconductivity with attractive properties for experimental control and scalability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay between superconductivity and magnetism in low-dimensional systems allows to engineer quantum phases absent in nature otherwise. Topological superconductors are paradigmatic examples, hosting Majorana-like quasiparticles at their boundaries or near defects. The exotic properties of these bound states, including their non-locality and non-Abelian exchange statistics, have attracted a growing interest in the field1,2,3,4,5,6. In particular, they are ideal platforms for encoding and processing quantum information in a protected way7.

Theory proposals suggested the onset of topological superconductivity in semiconductor (SM) nanowires with strong spin-orbit coupling when proximitized by a superconductor (SC)8,9. As an external magnetic field increases, the system undergoes a topological quantum phase transition, characterized by the closing and reopening of the superconducting gap. In the topological regime, sufficiently long wires feature zero-energy Majorana bound states at the ends. Robust zero-bias conductance peaks compatible in principle with Majorana states have been measured in nanowires over the last decade10,11,12,13,14. Later works have shown zero-energy states also in two-dimensional (2D) SM/SC hybrids15,16,17,18, an ideal platform for multi-wire designs with a measured high mobility19,20,21. However, the strong external magnetic field needed for the topological transition is detrimental to superconductivity and sets strict constraints on the device geometry, since the applied field needs to be oriented parallel to each wire. This is an obstacle for experiments showing Majorana non-Abelian properties22 and, ultimately, for topological quantum devices. Devices based on magnetic flux through full-shell nanowires23,24,25 and the phase difference in superconducting junctions26,27,28 are alternatives considered recently. However, these designs offer drawbacks for device scaling, due to their magnetic field direction sensitivity or the difficulty of controlling the phase difference between many superconductors.

In this context, ferromagnetic insulators (FIs) offer a way to solve the above problems by inducing a local exchange field on the SM nanowire by proximity effect, eliminating the need for external magnetic fields. Recent experiments in hexagonal nanowires partially covered by overlapping SC and FI shells showed the appearance of zero-bias conductance peaks29, spin-polarized subgap states30, and supercurrent reversal31. Concurrent theoretical works demonstrated the possibility of topological superconductivity in these tripartite systems by a combination of a direct induced exchange from the FI into the SM and an indirect one through the SC (present only in overlapping devices)32,33,34,35,36,37. A third mechanism whereby electrons tunnel from the SC to the SM through the spin-polarized FI barrier was identified for sufficiently thin FI layers in configurations where the SC and the SM are separated by the FI layer36,38. We note that in devices where the three materials are in direct contact, a sharp distinction between the three mechanisms is artificial and the overall induced exchange field is due to a combination of all of them. In general, fine-tuning from back and side gates was necessary in order to push the SM electron wavefunction close to both the SC and FI layers, maximizing magnetic and superconducting correlations.

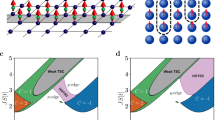

In this work we propose a planar SM/FI/SC heterostructure for the creation of a field-free quasi-one dimensional (1D) topological superconductor, Fig. 1(a). In this setup, a thin FI layer is grown between the SC and the SM. We note that, in principle, a planar SC/SM/FI heterostructure can also exhibit topological properties. However, we do not consider such an arrangement of materials because the growing conditions would lead to a highly disordered heterostructure. Due to the band alignment properties between materials, see Fig. 1(b), a charge accumulation layer appears at the SM/FI interface34, hosting a two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG). The role of the FI layer is two-fold: to induce an exchange field in the 2DEG and the SC, and to act as a spin-polarized barrier for electrons. In addition, a SC stripe on top of the FI layer defines a quasi-1D geometry where superconductivity is induced. State-of-the-art 2DEG platforms are usually grown on top of rather thick substrates, making it hard to gate them from the bottom. For this reason, we include a top gate in our design, used to manipulate the wavefunction profile in the SM region and drive the system in and out of the topological phase.

a Sketch of the device studied in this work: 2D semiconductor (SM)/ferromagnetic insulator (FI)/superconductor (SC) heterostructure stacked in the z-direction and infinite in the x-direction. The substrate is insulating and typically composed of several stacked semiconducting layers. The top gate can be used to confine the wavefunction below the grounded SC. The thickness of the ferromagnetic insulator layer dFI is varied to optimize the topological properties. b Schematics of the conduction-band bottom along the heterostructure stacking direction for a specific choice of materials (InAs/EuS/Al) and representative geometrical parameters (dSM = 10 nm, dFI = 2 nm, dSC = 8 nm and LSC = 100 nm). Red and blue colors represent different spin directions, and the gray dashed line depicts the Fermi level.

To test the properties of this device, we carry out microscopic simulations using a unified numerical approach33,39 that describes the electrostatic environment and treats the three different materials on an equal footing. Using specifically an InAs/EuS/Al heterostructure, a robust topological phase appears when the FI thickness is between ~1.5 nm and ~3 nm, equivalent to 2–5 EuS monolayers. It approximately corresponds to the wavefunction penetration length into the FI. In the Supplementary information (SI), we compare our results with the hexagonal cross-section nanowire geometry, illustrating that our 2D proposal provides larger and more regular topological regions as the external gate is varied, which moreover displays larger and harder gaps. We associate this behavior with the stronger vertical confinement achieved in 2DEGs compared to hexagonal nanowires. Therefore, our work establishes 2D ferromagnetic heterostructures as a promising platform for topological superconductivity, opening the possibility of defining complex topological wire structures.

Results

Model

Following ref. 33, we describe the heterostructure in Fig. 1a with a Bogoliubov-de Gennes Hamiltonian that includes the conduction band electrons in the three materials. In the Nambu basis \({{{\Psi }}}_{{k}_{x}}=({\psi }_{{k}_{x}\uparrow },{\psi }_{{k}_{x}\downarrow },{\psi }_{-{k}_{x}\uparrow }^{{\dagger} },{\psi }_{-{k}_{x}\downarrow }^{{\dagger} })\), it is given by

where σi and τj are the Pauli matrices in spin and Nambu space. We consider a translation invariant system in the x-direction. Therefore, the position and momentum operators read as \(\overrightarrow{r}=(y,z)\) and \(\overrightarrow{k}=({k}_{x},-i{\partial }_{y},-i{\partial }_{z})\) in the above Hamiltonian, with kx being a good quantum number. The model parameters are the effective mass m*, the conduction-band bottom EF, the exchange field hx (non-zero only in the FI), and the superconducting pairing potential Δ (non-zero only in the SC). Note that \({{\Delta }}(\overrightarrow{r})\) is real in the above equation. These parameters have a constant value inside each material. For our calculations, we use InAs for the SM, EuS as FI, and Al as SC. The material parameters are given in Supplementary Table I in the SI according to estimations and measurements that can be found in the literature. We also include quenched disorder in the outer surface of the SC, that is characteristic of this kind of heterostructures and beneficial for the superconducting proximity effect33,39. We have found that disorder in the FI (e.g., due to the corrugation of the EuS-Al interface40) does not significantly change the energy spectrum (not shown). Together with this, we include the electrostatic interactions \(\phi (\overrightarrow{r})\) of the stacking of Fig. 1a by solving self-consistently the Schrödinger-Poisson equation in the Thomas–Fermi approximation39,41,42, as explained in Sec. Methods and in the SI.

Topological phase transition

The low-energy wavefunctions decay exponentially in the FI layer on a length scale approximately given by \({\xi }_{{{{\rm{FI}}}}}=\sqrt{2{E}_{{{{\rm{F,FI}}}}}{m}_{{{{\rm{FI}}}}}^{* }/{\hslash }^{2}}\), where EF,FI is the conduction band minimum in the FI with respect to the Fermi level. For our materials choice ξFI ≈ 2.3 nm. As a consequence, the thickness of the FI layer determines the tunneling amplitude between the 2DEG and the SC: thicker FI layers decouple the 2DEG from the SC resulting in a reduction of the superconducting proximity effect, while thinner ones exhibit a reduced induced magnetization in the 2DEG. Hence, there is an optimal barrier thickness that allows for a sufficiently large induced exchange field and pairing potential in the 2DEG to drive the system into the topological regime.

The topological phase transition of the system occurs at a gap closing and reopening when the lowest energy subband crosses zero energy at the kx = 0 high symmetry point. For this reason, in Fig. 2 we show the energy spectrum of the system at kx = 0 as a function of the top-gate voltage for three different values of the FI thickness (dFI). The white (gray) background denotes the topological (trivial) phase, determined by the corresponding topological invariant.

Top row: energy spectrum at kx = 0 as a function of the top-gate voltage Vtg for a FI thickness of (a) dFI = 1 nm, (b) dFI = 1.5 nm and (c) dFI = 4 nm. Colors represent the weight WSC of each state in the superconducting Al layer. Shaded Vtg regions are those characterized by a trivial phase, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}=+1\); while white regions correspond to a topological phase, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{Q}}}}=-1\). Bottom row (d, e, f): effective exchange coupling heff (solid lines) and superconducting pairing amplitude Δeff (dotted lines) for the lowest-energy state in (a), (b), (c), respectively, as given by Eqs. 2 and 3.

Left panels in Fig. 2 show the regime where the FI is too thin to induce a topological phase transition. The energy spectrum shows low-energy bands localized mainly in the SC, represented by the black color in Fig. 2a. In this case, superconductivity dominates the properties of the low-energy modes. In Fig. 2d we show the effective superconducting pairing amplitude (dotted line) and exchange coupling (solid line) calculated using Eqs. 2 and 3. For this thickness, we observe that heff is mostly below Δeff, consistent with the system being in the trivial regime as the topological criterion \(\left|{h}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right|\gtrsim \sqrt{{{{\Delta }}}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{2}+{\mu }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{2}}\) cannot be fulfilled.

The situation becomes more favorable for FI layers of intermediate thickness, middle panels in Fig. 2. As a function of Vtg, the system shows several topological transitions when consecutive subbands cross zero energy. The topological regions are characterized by a non-trivial topological invariant and are marked by a white background in Fig. 2b and e. In these regions, the lowest-energy wavefunction has a significant weight in both the SC and the SM, as illustrated by the purple line color. The topological transition is associated with an increase of heff, overcoming the value of Δeff, see Fig. 2e. In the SI, we further illustrate that the topological criterion in 1D is fulfilled. The small deviations found are due to the approximated character of the effective parameters. We note that, for the optimal range of dFI, every subband can be tuned to the topological regime as Vtg is varied, in contrast to the hexagonal wire case where some subbands do not show a topological crossing, see for instance ref. 33 or the SI. This is due to the effective hard-wall confinement of the wavefunction in the thin SM layer in the z-direction [see Fig. 1a], which keeps the wavefunction close to the FI/SC layers for every subband. As a consequence, the device shows a regular alternation of trivial and topological regions against Vtg with comparable minigaps. The topological regions thus occupy a larger area in parameters space compared to the hexagonal wire case, where the appearance of the topological regions is more erratic, since the wavefunction can spread throughout the wide hexagonal section, sometimes avoiding a good proximity effect with the SC/FI layers.

The situation of a too-thick FI barrier is illustrated in the right panels of Fig. 2. A thick barrier hinders tunneling through the FI, preventing the hybridization of SC and 2DEG states. The reduced hybridization between the two materials can be seen from the shape of the spectrum in Fig. 2c, where the system shows an almost horizontal black line at the SC gap (E ~ 0.23 meV) and a series of almost vertical lines (orange dots) crossing the gap. This is also manifested in the abrupt transitions of effective parameters in Fig. 2f. When Δeff > heff the ground-state wavefunction is localized mostly in the SC and it is essentially independent of the gate voltage, whereas when Δeff < heff it is localized mostly in the SM. We note that the regions with a large effective exchange field also exhibit a suppressed superconducting pairing, consistent with normal gapless states in the SM.

Topological Phase Minigap

The properties of a topological superconductor are highly dependent on the value and quality of the topological minigap, which we examine now. In Fig. 3, we consider a device with dFI = 1.5 nm as we sweep Vtg. We show the energy subbands versus momentum kx and the spin-resolved density of states (DOS) in three representative situations: before (left column), at (middle column), and after (right column) the topological transition. Before the transition, Fig. 3a, the heterostructure features a trivial gap and the above-gap states are mostly localized in the SC (black color curves). The DOS displays a hard gap around zero energy and the characteristic spin-split superconducting coherence peaks, see red and blue curves in Fig. 3d. From this plot we infer that the induced exchange field in the SC is around 100 μeV (~50% of the Al gap), consistent with the value found in experiments43,44,45. A similar peak splitting is found in Fig. 3e, f, i.e., it is independent of the value of the gate potential.

Dispersion relation for a device with EuS layer thickness dFI = 1.5 nm, and for (a) Vtg = − 925 mV (before the topological transition), (b) Vtg = − 900 mV (at the topological transition), and (c) Vtg = − 850 V (in the middle of the topological phase). In (d–f) we show the spin-resolved integrated DOS of the corresponding plot on the top. Only the (c, f) case is topological, with \({E}_{\min }\) being the topological minigap, i.e., the lowest-state energy at kx = kF.

At the topological transition, one subband crosses zero energy at kx = 0, Fig. 3b. It results in a finite DOS inside the superconducting gap, see Fig. 3e. As we increase Vtg, the superconducting gap reopens in the topological phase, Fig. 3c, accompanied by the onset of Majorana bound states at the ends of a finite-length quasi-1D wire defined by the SC stripe (not shown). The hard gap found in Fig. 3f, \({E}_{\min }\), has a typical value of tens to a hundred μeV. We associate the large topological gaps found in these devices with the electrostatic confinement in the vertical direction. The thin SM layer, together with the top gate tuned to negative values, makes it possible to concentrate the weight of the wavefunction in the region where superconductivity, magnetism, and spin-orbit coupling coexist. This is signaled by the purple color of the lowest-energy subband in Fig. 3(c).

The importance of the wavefunction localization is illustrated in Fig. 4, which shows the lowest-energy wavefunction probability density across the device. In the topological regime, Fig. 4a, the ground state wavefunction is concentrated below the SC, maximizing the proximity effects of the SC and FI layers on top. The vertical confinement (in the z-direction) is determined by the SM width, dSM, and the fact that there is an insulating substrate below. The lateral confinement (in the y-direction) is achieved by a negative top-gate voltage that depletes the SM everywhere except below the SC. We note that the SM wavefunction penetrates the FI layer all the way to the SC due to its moderate gap and thickness. In the trivial regime shown in Fig. 4b, the wavefunction spreads laterally through all the device cross-section (due to a Vtg value comparable to or larger than the band bending at the SM/FI interface), reducing the proximity effects.

a Transverse probability density at kx = 0 for the lowest-energy state in a topological regime (Vtg = − 850 mV). For comparison, we also show in (b) the case in a topologically trivial regime (Vtg = 300 mV). Parameters are the same as in Fig. 3, corresponding to dFI = 1.5 nm.

Optimal Thickness of the FI

Finally, we vary the FI thickness to extract the optimal range for topological superconductivity, Fig. 5. The effective exchange coupling is shown in Fig. 5a and the effective superconducting pairing in Fig. 5b. The transverse modes considered (depicted with different colors) are the first four lowest-energy subbands that get populated starting from a depleted SM as we increase Vtg. For each calculated point, we tune Vtg to the value where the subband is closer to the Fermi level (E = 0), where heff is maximum, see Fig. 2e, f. Therefore, each point corresponds to a different Vtg value. We observe that in general heff increases with dFI because of the growing weight of the wavefunction inside the FI. In contrast, the effective superconducting pairing decreases with the FI thickness as the weight of the wavefunction in the SC diminishes.

a Effective ferromagnetic exchange coupling heff, (b) effective superconducting pairing amplitude Δeff, and (c) topological minigap \({E}_{\min }=| E({k}_{x}={k}_{F})|\) for the first four occupied transverse subbands (in different colors) versus the EuS thickness dFI. We extract these effective parameters when the subband is close to the Fermi level (E = 0), and therefore different points necessarily correspond to different Vtg values. Shaded regions and dashed lines represent that the system is characterized by a topologically trivial phase (and therefore there is no minigap). The suitable FI thickness dFI for topological superconductivity in the 2D stacking device proposed in this work ranges from ~1.5 to ~3 nm.

The topological minigap is shown in Fig. 5c. It is calculated for the value of Vtg that maximizes \({E}_{\min }\) for each subband, i.e., well within the topological region. Depending on the transverse mode, its value ranges from tens to a hundred μeV. Note that we have used the bulk SC gap for the Al layer, Δ0 = 230 μeV. Nevertheless, SCs with larger gaps such as Pb, Nb, Ta, V, or Sn, which can also be grown epitaxially over InAs46,47,48,49, could help to increase the topological minigap. Interestingly, for the small SM thickness considered here (10 nm), \({E}_{\min }\) is essentially constant with dFI for every transverse mode. This is again a consequence of the vertical confinement that tends to produce regular topological patterns. This regularity gets lost as the SM layer is made thicker, as shown in the SI. In this Appendix we also investigate the role of the SC thickness, finding similar results for thicknesses between 4 nm and 12 nm. For a SC with surface disorder, as the one considered here, the induced gap remains essentially unchanged and the main effect of the SC thickness is the renormalization of the SM chemical potential, shifting the picture described in Fig. 2b and e to lower/higher Vtg values. Thus, the main properties of the topological phase, i.e., regularity, extension, and robustness, do not significantly change, just the value of the top-gate voltage one needs to apply to populate the different subbands.

Lastly, we have compared our results for the proposed 2D planar heterostructure with a similar stacking in hexagonal nanowires, see the SI. The hexagonal nanowire can also be tuned to the topological regime using an electrostatic gate. However, the topological phase appears for reduced and irregular gate-voltage ranges compared to the planar structure in Fig. 1. In addition, the topological gap in hexagonal nanowires is typically soft, exhibiting low-energy trivial states. These states are prone to creating quasiparticle excitations poisoning, undermining coherence in the device and being an obstacle to topological superconductivity. We associate the improved topological properties of the presented 2D stacking with the vertical confinement of the 2DEG wavefunction (see Fig. 11 in the SI). In contrast, since the quantum well in hexagonal wires is less confined, the wavefunction can spread several nanometers away from the SC/FI interface, giving rise to weaker proximity effects. Moreover, due to the smaller wavefunction localization, the effective parameters are highly dependent on the wavefunction profile (or subband) and, consequently, the phase diagram appears to be more irregular than in the planar device.

Discussion

In this work we have proposed a planar heterostructure for topological superconductivity using a thin ferromagnetic insulator (FI) between a two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) and a superconductor (SC). The thin FI acts as a spin-filter barrier for electrons tunneling through, inducing a sufficiently large exchange field that gives rise to a topological transition in the tripartite heterostructure. In this geometry, superconducting stripes define quasi-1D wires that can be gated from the top, avoiding bottom gates that might be ineffective due to the rather thick substrates needed to create high-quality semiconducting heterostructures.

For illustration, we have considered an experimentally tested material combination: InAs (SM), EuS (FI), and Al (SC). We have found topological regions for FI thicknesses between 1.5 and 3 nm. Outside this range, the FI is either too thick to allow tunneling between the SC and the SM, or too thin to have a significant influence on the SM electrons. The topological phase features a hard superconducting gap in a range between tens to a 100μeV. This constitutes a significant improvement with respect to previous hexagonal nanowire geometries29,33,34, where these gaps were only possible by fine-tuning side gates to push the wavefunction sufficiently close to the FI/SC layers. We associate this behavior to the vertical confinement of the wavefunction for thin SM layers. Most importantly, this vertical confinement also helps to create a rather regular phase diagram, with topological and trivial phases appearing at controlled values of the top-gate potential. The topological regions produced by the subsequent inverting subbands have moreover a similar Vtg-range and comparable topological minigaps. Experimentally, this is an advantageous property since it permits to search for the topological phase in a predictable manner rather than by randomly scanning parameters, as it is typically the case with hexagonal nanowires.

Concerning the experimental detection of Majorana states in this system, the planar platform offers the possibility to perform local tunneling spectroscopy to detect the presence of low-energy states bound to the wire’s end. Examples of such experiments in a planar geometry (in the absence of the FI) can be found in refs. 15,16. Correlations between two or more local probes along the quasi-1D wire and non-local transport spectroscopy have just begun to be explored in planar devices50,51. Another common tool to try to detect the presence of Majoranas is the anomalous behavior of the Josephson effect. Actually, phase-dependent zero-bias conductance peaks measured by tunneling spectroscopy at the end of Josephson junctions, as well as phase-dependent critical currents, have been studied recently in planar SM/SC heterostructures18,28,52 (again, in the absence of the FI but with applied magnetic field). Differently from hexagonal nanowires, the 2D structures described here require no magnetic field to reach the topological phase, allowing for different orientations of the effective wires and the design and control of complex wire networks of topological superconductors. This opens the door to more sophisticated and reliable Majorana detection experiments based on the spatial exchange or fusion of the Majorana bound states53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62.

Note added.– During the preparation of this manuscript, an independent work on a similar subject has been made available as a preprint63. Their results are consistent with the ones of this article. The authors study a similar stacking of materials, although there are some differences with our setup. The SC occupies the whole width of the planar heterostructure (instead of being a SC stripe like in our proposal) and they use periodic boundary conditions in the y-direction for its description. They moreover gate the system from the bottom and the exchange field is oriented in the z-direction. Despite of this, we agree on the main conclusion that the FI thickness should be of the order of the wavefunction penetration length in order to find topological superconductivity.

Methods

Electrostatic interactions

We firstly describe the electrostatic interactions in the stacking of Fig. 1a by solving self-consistently the Schrödinger–Poisson equation in the Thomas–Fermi approximation39,41,42. We take into account the band bending produced at the InAs/EuS interface34,64, see Fig. 1b, using a fixed positive surface charge in our simulations. This strong band-bending is crucial as it induces a natural 2DEG at the SM/FI interface, enhancing the topological properties of the device by confining electrons close to the proximitized region33,34. Then, a quasi-1D system can be defined by means of an electrostatic lateral confinement. This is achieved by applying a negative potential to the top gate that depletes the 2DEG everywhere except underneath the grounded SC stripe, which screens the electric field coming from the top gate. This allows controlling the lateral extension (in the y-direction) of the SM 1D channels. Moreover, the top gate allows for partial control of the local chemical potential in the effective wire. Our design is independent of the choice of the specific materials as long as they fulfill some requirements: the SM should feature a surface 2DEG, whereas the FI should have a moderate bandgap to allow electron tunneling, and a sufficiently large spin-splitting to induce the topological transition (but small enough not to suppress superconductivity in the SC).

Additional details on the electrostatic problem can be found in the SI. We obtain the self-consistent electrostatic potential \(\phi (\overrightarrow{r})\) across the heterostructure along with the Rashba field \({\overrightarrow{\alpha }}_{R}(\overrightarrow{r})\), non-zero only in the SM. The Rashba coupling is proportional to the electric field \(\overrightarrow{\nabla }\phi (\overrightarrow{r})\), which is mainly oriented in the z-direction, and it is accurately described using the procedure of ref. 65 and further discussed in the SI. The spin-orbit field (\(\sim\!\!\overrightarrow{k}\times {\overrightarrow{\alpha }}_{R}\)) is mainly oriented in the y-direction (~αR,zkxσy), with small components in the x and z-directions. We have verified that the electric field in the FI is negligible and, therefore, \(\phi (\overrightarrow{r})\) is disregarded in that region in Eq. 1.

Ferromagnetic insulator layer

We describe the FI as a depleted wide-bandgap semiconductor with a spin-split conduction band laying above the Fermi level, as depicted schematically Fig. 1b. The topological phase can appear when the FI magnetization is not aligned with the spin-orbit field (which is oriented fundamentally in the y-direction in our device), and it is maximized when the magnetization and the spin-orbit field are perpendicular. In this work we assume that the FI exhibits a homogeneous in-plane magnetization along the x-direction and negligible stray fields, consistent with the measured easy-axis in thin EuS40. We note that our setup could tolerate in principle an arbitrary misalignment of the exchange field in the z-direction since this would still be perpendicular to the spin-orbit term. This is an advantage with respect to schemes relying on external magnetic fields, where relatively small perpendicular magnetic fields to the SC layer suppress superconductivity due to orbital effects.

Effective single-band parameters

After the calculation of the electrostatic interactions, we discretize the continuum Hamiltonian in Eq. 1 following a finite differences scheme with a grid of 0.1 nm. We diagonalize the resulting sparse Hamiltonian for different top-gate voltages Vtg, and longitudinal momenta kx using the routines implemented in ref. 66. From the low-energy eigenstates \({{{\Psi }}}_{{k}_{x}}(\overrightarrow{r})\) we obtain the topological invariant33,67,68,69 and estimate the effective parameters heff and Δeff for the lowest-energy one as

where Wβ is the weight of the lowest-energy state in the material \(\beta =\left\{{{{\rm{SC}}}},{{{\rm{FI}}}}\right\}\), σ0 and τ0 are the identity matrices in spin and Nambu space, and h0 and Δ0 are the parent exchange coupling in the FI and the parent superconducting pairing in the SC, respectively. The estimation in Eqs. 2 and 3 is valid for any subgap state (\(\left|{E}_{n}\right| \,<\, {{{\Delta }}}_{0}\)) when the heterostructure thicknesses dSM ≪ λSO and dSC ≪ ξSC, being λSO the spin-orbit length and ξSC the superconducting coherence length. Additional details can be found in the SI. heff and Δeff can be interpreted as the parameters entering in an effective single-band Oreg-Lutchyn Hamiltonian8,9 describing the lowest-energy subband. These quantities, together with the effective chemical potential μeff, are useful to understand when the system undergoes a topological phase transition, as a large enough exchange field is needed to fulfill the 1D topological criterion, i.e., \(\left|{h}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}\right|\gtrsim \sqrt{{{{\Delta }}}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{2}+{\mu }_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}^{2}}\)8.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alicea, J. New directions in the pursuit of Majorana fermions in solid state systems. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 076501 (2012).

Leijnse, M. & Flensberg, K. Introduction to topological superconductivity and Majorana fermions. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 27, 124003 (2012).

Aguado, R. Majorana quasiparticles in condensed matter. Riv. del. Nuovo Cim. 40, 523–593 (2017).

Prada, E. et al. From Andreev to Majorana bound states in hybrid superconductor–semiconductor nanowires. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 575–594 (2020).

Lutchyn, R. M. et al. Majorana zero modes in superconductor-semiconductor heterostructures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 52–68 (2018).

Flensberg, K., von Oppen, F. & Stern, A. Engineered platforms for topological superconductivity and Majorana zero modes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 944–958 (2021).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Oreg, Y., Refael, G. & von Oppen, F. Helical liquids and Majorana bound states in quantum wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 177002 (2010).

Lutchyn, R. M., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Majorana fermions and a topological phase transition in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 077001 (2010).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Das, A. et al. Zero-bias peaks and splitting in an Al-InAs nanowire topological superconductor as a signature of Majorana fermions. Nat. Phys. 8, 887–895 (2012).

Deng, M. T. et al. Majorana bound state in a coupled quantum-dot hybrid-nanowire system. Science 354, 1557–1562 (2016).

Gül, Ö. et al. Hard superconducting gap in InSb nanowires. Nano Lett. 17, 2690–2696 (2017).

Grivnin, A., Bor, E., Heiblum, M., Oreg, Y. & Shtrikman, H. Concomitant opening of a bulk-gap with an emerging possible Majorana zero mode. Nat. Commun. 10, 1940 (2019).

Suominen, H. J. et al. Zero-energy modes from coalescing Andreev states in a two-dimensional semiconductor-superconductor hybrid platform. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 176805 (2017).

Nichele, F. et al. Scaling of Majorana zero-bias conductance peaks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 136803 (2017).

Hell, M., Flensberg, K. & Leijnse, M. Coupling and braiding Majorana bound states in networks defined in two-dimensional electron gases with proximity-induced superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 96, 035444 (2017).

Fornieri, A. et al. Evidence of topological superconductivity in planar Josephson junctions. Nature 569, 89–92 (2019).

Kjaergaard, M. et al. Quantized conductance doubling and hard gap in a two-dimensional semiconductor-superconductor heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 7, 12841 (2016).

Lee, J. S. et al. Transport studies of epi-al/inas two-dimensional electron gas systems for required building-blocks in topological superconductor networks. Nano Lett. 19, 3083–3090 (2019).

Ahn, S., Pan, H., Woods, B., Stanescu, T. D. & Das Sarma, S. Estimating disorder and its adverse effects in semiconductor Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 124602 (2021).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Search for non-Abelian Majorana braiding statistics in superconductors. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes15 (2020).

Vaitiekėnas, S. et al. Flux-induced topological superconductivity in full-shell nanowires. Science 367, eaav3392 (2020).

Peñaranda, F., Aguado, R., San-Jose, P. & Prada, E. Even-odd effect and Majorana states in full-shell nanowires. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023171 (2020).

Valentini, M. et al. Nontopological zero-bias peaks in full-shell nanowires induced by flux-tunable Andreev states. Science 373, 82–88 (2021).

Pientka, F. et al. Topological superconductivity in a planar Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021032 (2017).

Lesser, O. & Oreg, Y. Majorana zero modes induced by superconducting phase bias. J. Phys. D. 55, 164001 (2022).

Banerjee, A. et al. Signatures of a topological phase transition in a planar Josephson junction. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.03453 (2022).

Vaitiekėnas, S., Liu, Y., Krogstrup, P. & Marcus, C. M. Zero-bias peaks at zero magnetic field in ferromagnetic hybrid nanowires. Nat. Phys. 17, 43–47 (2021).

Vaitiekėnas, S. et al. Evidence for spin-polarized bound states in semiconductor–superconductor–ferromagnetic-insulator islands. Phys. Rev. B 105, L041304 (2022).

Razmadze, D. et al. Supercurrent reversal in ferromagnetic hybrid nanowire Josephson junctions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.03202 (2022).

Woods, B. D. & Stanescu, T. D. Electrostatic effects and topological superconductivity in semiconductor–superconductor–magnetic-insulator hybrid wires. Phys. Rev. B 104, 195433 (2021).

Escribano, S. D., Prada, E., Oreg, Y. & Yeyati, A. L. Tunable proximity effects and topological superconductivity in ferromagnetic hybrid nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 104, L041404 (2021).

Liu, C.-X. et al. Electronic properties of InAs/EuS/Al hybrid nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 104, 014516 (2021).

Khindanov, A., Alicea, J., Lee, P., Cole, W. S. & Antipov, A. E. Topological superconductivity in nanowires proximate to a diffusive superconductor–magnetic-insulator bilayer. Phys. Rev. B 103, 134506 (2021).

Maiani, A., Seoane Souto, R., Leijnse, M. & Flensberg, K. Topological superconductivity in semiconductor–superconductor–magnetic-insulator heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 103, 104508 (2021).

Pöyhönen, K., Varjas, D., Wimmer, M. & Akhmerov, A. R. Minimal Zeeman field requirement for a topological transition in superconductors. SciPost Phys. 10, 108 (2021).

Langbehn, J., Acero González, S., Brouwer, P. W. & von Oppen, F. Topological superconductivity in tripartite superconductor-ferromagnet-semiconductor nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 103, 165301 (2021).

Winkler, G. W. et al. Unified numerical approach to topological semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 99, 245408 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Semiconductor-ferromagnetic insulator-superconductor nanowires: stray field and exchange field. Nano Lett. 20, 456–462 (2020).

Mikkelsen, A. E. G., Kotetes, P., Krogstrup, P. & Flensberg, K. Hybridization at superconductor-semiconductor interfaces. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031040 (2018).

Escribano, S. D., Levy Yeyati, A., Oreg, Y. & Prada, E. Effects of the electrostatic environment on superlattice Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 100, 045301 (2019).

Hao, X., Moodera, J. S. & Meservey, R. Thin-film superconductor in an exchange field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1342–1345 (1991).

Strambini, E. et al. Revealing the magnetic proximity effect in EuS/Al bilayers through superconducting tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 054402 (2017).

Rouco, M. et al. Charge transport through spin-polarized tunnel junction between two spin-split superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 100, 184501 (2019).

Kanne, T. et al. Epitaxial Pb on InAs nanowires for quantum devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 776–781 (2021).

Bjergfelt, M. et al. Superconducting vanadium/indium-arsenide hybrid nanowires. Nanotechnology 30, 294005 (2019).

Khan, S. A. et al. Highly transparent gatable superconducting shadow junctions. ACS Nano 14, 14605–14615 (2020).

Carrad, D. J. et al. Shadow epitaxy for in situ growth of generic semiconductor/superconductor hybrids. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908411 (2020).

Pöschl, A. et al. Nonlocal signatures of hybridization between quantum dot and Andreev bound states. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.03687 (2022).

Pöschl, A. et al. Nonlocal conductance spectroscopy of Andreev bound states in gate-defined InAs/Al nanowires. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.02430 (2022).

Nichele, F. et al. Relating Andreev bound states and supercurrents in hybrid Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 226801 (2020).

Bonderson, P., Freedman, M. & Nayak, C. Measurement-only topological quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 010501 (2008).

Alicea, J., Oreg, Y., Refael, G., von Oppen, F. & Fisher, M. P. A. Non-Abelian statistics and topological quantum information processing in 1D wire networks. Nat. Phys. 7, 412–417 (2011).

Flensberg, K. Non-Abelian operations on Majorana fermions via single-charge control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 090503 (2011).

van Heck, B., Akhmerov, A. R., Hassler, F., Burrello, M. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Coulomb-assisted braiding of Majorana fermions in a Josephson junction array. N. J. Phys. 14, 035019 (2012).

Aasen, D. et al. Milestones toward Majorana-based quantum computing. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031016 (2016).

Vijay, S. & Fu, L. Teleportation-based quantum information processing with Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 94, 235446 (2016).

Karzig, T. et al. Scalable designs for quasiparticle-poisoning-protected topological quantum computation with Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 95, 235305 (2017).

Plugge, S., Rasmussen, A., Egger, R. & Flensberg, K. Majorana box qubits. N. J. Phys. 19, 012001 (2017).

Krøjer, S., Seoane Souto, R. & Flensberg, K. Demonstrating Majorana non-Abelian properties using fast adiabatic charge transfer. Phys. Rev. B 105, 045425 (2022).

Seoane Souto, R. & Leijnse, M. Fusion rules in a Majorana single-charge transistor. SciPost Phys. 12, 161 (2022).

Liu, C.-X. & Wimmer, M. Optimizing the topological properties of semiconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 105, 224502 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Coherent epitaxial semiconductor-ferromagnetic insulator InAs/EuS interfaces: band alignment and magnetic structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 8780–8787 (2020).

Escribano, S. D., Yeyati, A. L. & Prada, E. Improved effective equation for the rashba spin-orbit coupling in semiconductor nanowires. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033264 (2020).

Escribano, S. D. Majorana nanowires: quantum simulation package. https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/192539285 (2020).

Loring, T. A. & Hastings, M. B. Disordered topological insulators via C*-algebras. EPL 92, 67004 (2010).

Zhang, Y.-F. et al. Coupling-matrix approach to the chern number calculation in disordered systems. Chin. Phys. B 22, 117312 (2013).

Lesser, O. & Oreg, Y. Universal phase diagram of topological superconductors subjected to magnetic flux. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023063 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge insightful discussions with C. Marcus, S. Vaitiekėnas, L. Galletti, Y. Liu, and C. Schrade. This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through Grants No. PID2020- 11767GB- I00, No. PCI2018-093026, and No. PGC2018-097018- B-I00 (AEI/FEDER, EU), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the FETOPEN Grant Agreement No. 828948 (AndQC) and the María de Maeztu Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D, Grant No. MDM-2014-0377. We also acknowledge support from the Danish National Research Foundation, the Danish Council for Independent Research ∣Natural Sciences, the European Research Council (Grant Agreement No. 856526), the Swedish Research Council, and NanoLund. The research at WIS was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement LEGOTOP No. 788715), the DFG (CRC/Transregio 183, EI 519/7-1), the BSF and NSF (2018643), and the ISF Quantum Science and Technology (2074/19).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D.E. prepared the numerical codes, performed the simulations, and prepared the figures. E.P. and R.S.S. oversaw the project. S.D.E., A.M., E.P., and R.S.S. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all the authors. All authors contributed to designing the project and to the interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Escribano, S.D., Maiani, A., Leijnse, M. et al. Semiconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor planar heterostructures for 1D topological superconductivity. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 81 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-022-00489-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-022-00489-9

This article is cited by

-

Conductance spectroscopy of Majorana zero modes in superconductor-magnetic insulator nanowire hybrid systems

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Direct observation of a superconducting vortex diode

Nature Communications (2023)