Abstract

Multiorbital systems away from global half-filling host intriguing physical properties promoted by Hund’s coupling. Despite increasing awareness of this regime dubbed Hund’s metal, effect of nonlocal interaction is still elusive. Here we study a three-orbital model with 1/3 filling (two electrons per site) including the intersite Coulomb interaction (V). Using the GW plus extended dynamical mean-field theory, the valence-skipping charge order transition is shown to be driven by V. Most interestingly, the instability to this transition is significantly enhanced in the spin-freezing crossover regime, thereby lowering the critical V to the formation of charge order. This behavior is found to be closely related to the population profile of the atomic multiplet states in the spin-freezing regime. In this regime, maximum spin states are dominant in each total charge subspace with substantial amount of one- and three-electron occupations, which leads to almost equal population of one- and the maximum spin three-electron state. Our finding unveils another feature of the Hund’s metal and has potential implications for the broad range of multiorbital systems as well as the recently discovered charge order in iron pnictides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Classifying a number of phases and understanding their relevance to different energy scales has been a central theme of condensed matter physics. In multiorbital systems away from global half-filling, Hund’s coupling was shown to promote a bad metallic behavior while simultaneously pushing away the Mott insulating region1,2,3. The term Hund’s metal4,5 was coined to classify the regime in which the “Hundness” not the “Mottness” plays a leading role in determining physical properties6,7. The Hund’s metal hosts rich phenomena, such as finite temperature spin-freezing crossover7,8,9, spin–orbital separation7,10,11,12,13,14, anomalous transport behavior3,4,8, increased electronic compressibility15,16, and the orbital differentiation2,17,18,19,20. It has been believed to be one of the central doctrines to understand the intriguing physics of (mainly but not limited to) iron-based superconductors3,4,5,15,16,17,18,21,22,23 and ruthenates3,8,24,25,26.

In addition to the above-mentioned direct manifestations of Hund’s metal regime, its connection and proximity to the symmetry-broken charge-disproportionated phases has recently been highlighted27,28. Those that are called Hund’s insulator27 and valence-skipping phase28,29,30—a phase with two different valences while skipping the intermediate one between the two—are prominent examples. One possible route to the valence-skipping is the negative effective Coulomb repulsion, Ueff < 0 refs 28,31,32. Interestingly, a purely intra-atomic origin, namely, the anisotropic orbital-multipole scattering, was suggested to be the key ingredient for such valence-skipping phenomena28. Furthermore, this phase has potential implications for the electron pairing mechanisms of unconventional superconductivity28,33.

The valence-skipping compounds are prevalent in Nature most evidently in the form of charge order (CO)28. The CO transition has actively been studied in the single-orbital extended Hubbard model presumably in close connection with the superconductivity of cuprates34. Notably, as in the case of cuprates, recent experiments reported the CO in the vicinity of the superconducting phase of AFe2As2 (A = Rb, K, Cs), archetypal materials of Hund’s metal35,36,37. Moreover, relevance of charge fluctuations or CO to the superconductivity of iron pnictides was reported38. Thus it is tempting to presume that the CO is a common “neighbor” of unconventional high-temperature superconductivity. On the other hand, one can also envisage the more complexity of the multiorbital CO transition due to the additional energy scales such as Hund’s coupling absent in single-orbital models.

In this work, by employing the state-of-the-art GW plus extended dynamical mean-field theory (GW+EDMFT) adapted to multiorbital models, we demonstrate that the valence-skipping CO is driven by intersite nonlocal Coulomb repulsion V, and the instability to this phase is significantly enhanced in the spin-freezing crossover regime. This enhancement is shown to be related to the local multiplet population profile. This route to the valence-skipping is distinctive from the anisotropic orbital-multipole scattering mechanism28.

Results and discussion

We first construct a following model for the two-dimensional square lattice including both local and nonlocal interaction terms:

where \({c}_{i\gamma \sigma }^{\dagger }\) (ciγσ) is the electron creation (annihilation) operator acting on site i with orbital index γ = 1, 2, 3 and spin index σ = ↑, ↓. t (t > 0) is the hopping amplitude between two nearest-neighbor (NN) sites denoted by 〈ij〉. We use half-bandwidth D = 4t as the unit of energy. \({n}_{i\gamma \sigma }={c}_{i\gamma \sigma }^{\dagger }{c}_{i\gamma \sigma }\) is the electron number operator. μ is the chemical potential to be adjusted to obey 1/3 filling per site; ∑γ,σ〈niγσ〉 = 2. Hloc is of the Kanamori form containing the onsite Coulomb repulsion U and the Hund’s coupling J, which reads

Hnonloc is the interaction term between two NN sites coupled via nonlocal Coulomb repulsion V,

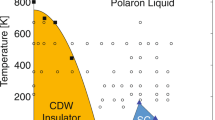

To gain a useful insight for CO transition of the model constructed in Eq. (1), we first investigate a simple case of vanishing t and temperature. This simple atomic limit—a limit where the lattice consists of atoms with zero t among them—enables us to get analytical solutions, which is found to be a good estimate even under nonzero t and temperature28,39,40,41,42. In Fig. 1, we plot the obtained phase diagram (see Supplementary Note 1 for more details). Three different phases are classified according to their valence. We used notation dN to denote the N-electron occupation of a site in the primitive cell. Note that the triple point emerges at V/U = 0 and J/U = 1/3, which corresponds to the parameter region where the metal resilient to Mott’s and Hund’s insulator transition emerges27, as well as the valence-skipping phases cease to exist28. The possible existence of d3 + d1 phase was previously noticed from the slave-boson mean field by solving the Kanamori Hamiltonian27. This state, however, is degenerate at J/U = 1/3 with d2 and 2d3 + d0 phases and never the ground state unless V/U > 0. The 2d3 + d0 phase is equivalent to the charge-ordered Hund’s insulator27. Note also that other COs such as d4 + d0 and 2d0 + d6 can be stabilized above the dashed lines depicted in Fig. 1, which are quite irrelevant for the present study.

At 0 < J/U < 1/3, we can observe a transition from the isotropic d2 to d3 + d1 valence-skipping CO with ordering wave-vector (π, π) at the critical V (Vc), \({V}_{{\rm{c}}}=\frac{U}{4}(1-3J/U)\). It should be noted that this phase is driven by V, not by the anisotropic orbital-multipole scattering since the Kanamori form is free from it by construction28. At J/U = 0, Vc follows the half-filled single-orbital result of Vc = U/4 refs 39,40.

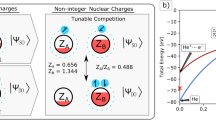

With insight obtained above, we now turn to our GW+DMFT results. The corresponding phase diagram obtained from GW+EDMFT is shown in Fig. 2a. We identified the CO transition by monitoring the divergence of the static charge susceptibility χ(k, iν0) (ν0 is the lowest bosonic Matsubara frequency, ν0 = 0). The divergence actually occurs at the wave vector k = (π, π) indicating the formation of d3 + d1 order (see Figs. 1 and 3b). One can also confirm that this CO transition is driven by V (compare Fig. 3b with Fig. 3a; see also Supplementary Note 3 for χ(k, iν0) at V = 0).

The solid lines represent Vc obtained from three different methods: a GW+EDMFT, b EDMFT, and c GW. The dotted lines represent Vc estimates from the analytical results at atomic limit (see Fig. 1). The skyblue region highlights the region of d3 + d1 phase.

χ(k, iν0) at a U = 1, J/U = 0.05, V = 0 and b U = 1, J/U = 0.05, V = 0.9Vc in the Brillouin zone. The color bars in a, b represent the magnitude of χ(k, iν0). c–f χ(Ri, iν0) as a function of distance. Insets in c, e highlight the contribution of the coordination number Zi of the ith NN and the resulting charge susceptibility.

The actual GW+EDMFT results roughly follow the atomic limit estimate at J/U ≤ 0.15 and are in fair agreement at large U(U = 3, 4) and J/U = 0.15. Even in smaller U region (Fermi liquid (FL); see Fig. 4a), GW+EDMFT results qualitatively follow the atomic limit estimates. This seemingly unusual behavior is attributed to the leading contribution of interaction energy compared to the kinetic energy in determining the CO transition boundary43. Note that the Mott phase emerges at V = 0 for U = 4 (when J/U = 0.05) and U = 5 (when J/U ≤ 0.15). In the current study, we restrict our discussion to the U and J/U region in which the metallic phase is obtained when V = 0.

a The correlation between the exponent α and Δχs/χs. U, J/U, and V are represented by color, point shape, and point size, respectively. Points belonging to the same U and J/U are connected with lines linking from V = 0 (the smallest point) to the largest V accessible in our numerics (the largest point). The behaviors of α and Γ as a function of V are shown for b J/U = 0.1 and c J/U = 0.2. Note that we used three lowest Matsubara frequencies in fitting \({\rm{Im}}{\Sigma }_{{\rm{loc}}}(i{\omega }_{n})\) to obtain α and Γ.

At J/U = 0.2, GW+EDMFT results exhibit unprecedented behavior at large U (U ≥ 3): CO instability is significantly enhanced, thereby pushing Vc further below the atomic limit estimates. Notably, the downturn of Vc is most pronounced at U = 4 followed by a rapid upturn of the phase boundary at U = 5. This behavior is not captured either by EDMFT or GW approximations (see Fig. 2b, c). On the other hand, at smaller U (U ≤ 2), Vc values obtained from GW+EDMFT are almost identical to those of EDMFT and larger than the atomic limit estimates. The discrepancy between GW results (Fig. 2c) and the others is reasonable since this method cannot properly treat the local physics. We briefly remark that, at further larger J/U, especially near J/U = 1/3 and V = 0 in which the triple point emerges in Fig. 1, a signature of the 2d3 + d0 phase is also expected. Notably, the presence of this degeneracy point is claimed to play an important role in stabilizing the metallic phase27. The triple degeneracy, however, should be lifted by nonzero V. We expect that an intriguing physics can happen due to this broken degeneracy, which we leave for future study.

To further illustrate the above intriguing result from GW+EDMFT at large U and J/U regime, we investigate the site-resolved charge susceptibility \(\chi ({{\bf{R}}}_{i},i{\nu }_{0})=\int {\rm{d}}{\bf{k}}{e}^{i{\bf{k}}\cdot {{\bf{R}}}_{i}}\chi ({\bf{k}},i{\nu }_{0})\) (Ri is the position vector of the ith NN). The magnitude of this quantity is enhanced as V increases as shown in Fig. 3c–f. Near the CO boundary (V ≃ 0.9Vc), the sign of χ(Ri, iν0) clearly indicates the CO instability at k = (π, π), which has to be plus (minus) for onsite, second, and third (first and fourth) NNs.

Most interestingly, the large U results exhibit the rapid growth of χ(Ri, iν0) as a function of J/U at a finite V (see Fig. 3f). This behavior is in contrast to the smaller U results in which the increase of χ(Ri, iν0) is much more gradual (see Fig. 3d). This enhancement of χ(Ri, iν0) at J/U = 0.2 is further manifested by the static effective local interaction, \({\mathcal{U}}(i{\nu }_{0})\). The intraorbital elements \({\mathcal{U}}{(i{\nu }_{0})}_{\gamma \gamma }\equiv {\mathcal{U}}{(i{\nu }_{0})}_{\gamma \gamma \gamma \gamma }\) at U = 4 and V ≃ 0.9Vc shows the large screening effect at J/U = 0.2; from \({\mathcal{U}}{(i{\nu }_{0})}_{\gamma \gamma }=3.31\) (3.39) at J/U = 0.1 (0.15) to \({\mathcal{U}}{(i{\nu }_{0})}_{\gamma \gamma }=2.88\) at J/U = 0.2. Note also that the substantial amount of nonlocal χ(Ri, iν0) exists even at V = 0 in the larger U and J/U = 0.2 regime (compare Fig. 3c, e and their insets).

Key information for understanding the large enhancement of CO instability is provided by investigating the local self-energy Σloc(iωn) (ωn: fermionic Matsubara frequency). Σloc(iωn) shows an interesting behavior near spin-freezing crossover regime3,8, which is a metal with emerging local moment: large spin susceptibility \({\chi }_{{\rm{s}}}={\int }_{0}^{\beta }d\tau \langle {S}_{i}(\tau ){S}_{i}(0)\rangle\) with substantial dynamic contribution of \(\Delta {\chi }_{{\rm{s}}}={\int }_{0}^{\beta }d\tau \left(\right.\langle {S}_{i}(\tau ){S}_{i}(0)\rangle -\langle {S}_{i}(\beta /2){S}_{i}(0)\rangle \left)\right.\)25. Si = (1/2)∑γ(niγ↑ − niγ↓) is the local spin operator. In this regime, \({\rm{Im}}{\Sigma }_{{\rm{loc}}}(i{\omega }_{n})\) is claimed to follow the power-law behavior at low frequency: \({\rm{Im}}{\Sigma }_{{\rm{loc}}}(i{\omega }_{n})\simeq -{\Gamma} +A{({\omega }_{n})}^{\alpha }\) with α ≃ 0.5 and Γ ≃ 08. Deep inside this crossover where non-FL behavior appears (Γ > 0 and α > 0.5) is called the frozen-moment regime3,8,25. In Fig. 4, we summarize our analysis of \({\rm{Im}}{\Sigma }_{{\rm{loc}}}(i{\omega }_{n})\).

Figure 4a shows the correlation between α and Δχs/χs. By construction, Δχs/χs lies in between 0 and 1. The limiting value of Δχs/χs indicates either the FL limit when Δχs/χs → 1 or the frozen-moment regime when Δχs/χs → 0. Thus we can naturally expect that the spin-freezing regime should lie somewhere in between these two limits. We identify the region of 0.4 ≲ α ≲ 0.5 and Γ ≃ 0 with the spin-freezing crossover regime. In our parameter range, spin-freezing regime appears for 0.25 < Δχs/χs < 0.4 (see also Supplementary Note 4 for the correlation of α with \({\chi }_{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) and Δχs). In FL regime, increasing V drives the system to be less correlated. Interestingly at U = 4 and J/U = 0.1, V drives the system from the (proximity of) frozen moment to FL and eventually to CO. This behavior can be confirmed by vanishing Γ and α > 0.5 near Vc (see Fig. 4b). We also note that EDMFT yields qualitatively similar results except that, at U = 4 and J/U = 0.1, increasing V do not show any signal of transition to the FL.

Most notably, the parameter region showing the unusual downturn of Vc (U = 3, 4 and J/U = 0.2) corresponds to the spin-freezing crossover regime. As U increases further at J/U = 0.2, an upturn of the phase boundary appears (see Fig. 2a) as entering deeper into the frozen moment regime. In this range of U and J/U, the increasing V tends to reduce α while maintaining Γ = 0 (see Fig. 4a, c). To further clarify the relation between the enhanced CO instability and the spin-freezing crossover, we investigate the local populations (or probabilities) of atomic multiplet states. The U(1)charge × SU(2)spin × SO(3)orbital symmetry of Eq. (2) allows us to have the simultaneous eigenstates of charge N, orbital L, and spin S as \(\left|N,L,S\right\rangle\)1,3,27. The local population profiles of these eigenstates are plotted in Fig. 5a, b as approaching the CO boundary.

The local multiplet populations are shown for a U = 4, J/U = 0.1, b U = 4, J/U = 0.15, and c U = 4, J/U = 0.2. Points with solid lines correspond to the maximum S states of each total charge subspace; (N, L, S) = (1, 1, 1/2), (2, 1, 1), and (3, 0, 3/2) indicated by blue (square), black (circle), and red (diamond) lines, respectively. Points with dashed lines belong to the remaining smaller S states of N = 2 (circle) and N = 3 (diamond) subspaces. d Vc estimate as a function of p1. The dashed lines correspond to the Vc at p1 = 0. The actual Vc obtained from GW+EDMFT are marked by filled circles (J/U = 0.1), triangles (J/U = 0.15), and stars (J/U = 0.2) (see also Fig. 2a).

One can notice that, in spin-freezing crossover regime, maximum S states are dominant in each total charge subspace with substantial amount of N = 1 and N = 3 populations (contribution of states other than N = 1, 2, 3 subspaces are negligible) (Fig. 5c). It is the effect of J favoring the maximum S. Importantly, these N = 1 and N = 3 charges are directly related to the d3 + d1 CO phase, which implies the enhanced CO instability in this regime. On the other hand, in the frozen moment regime, N = 2 population is more dominant with reduced N = 1 and N = 3 portions than the spin-freezing case; compare Fig. 5a, b with Fig. 5c. FL regime exhibits non-negligible excursions to every other \(\left|N,L,S\right\rangle\) as expected. We hereafter denote the population of \(\left|1,1,1/2\right\rangle\) and \(\left|3,0,3/2\right\rangle\) by p1 and p3.

At U = 4 and J/U = 0.2, only the maximum S is selected in the N = 3 subspace, leading to p3 ≃ p1 (see Fig. 5c). At U = 5 and J/U = 0.2 (frozen moment), p3 ≃ p1 is also found. This case, however, shows more dominant N = 2 population (~0.79 at V = 0) with reduced N = 1 and N = 3 contributions compared to the U = 4 and J/U = 0.2 case. In light of this observation, we construct a phenomenological local wave-function ψ consisting of maximum S states, namely, \(\psi =\sqrt{{p}_{1}}\left|1,1,1/2\right\rangle +\sqrt{1-2{p}_{1}}\left|2,1,1\right\rangle +\sqrt{{p}_{1}}\left|3,0,3/2\right\rangle\) apart from the phase factor, which is irrelevant for the evaluation of energy. The re-calculated Vc estimate (as is done for Fig. 1) by means of ψ is shown in Fig. 5d. We can observe the qualitative agreement with the actual behavior obtained from GW+EDMFT at J/U = 0.2 (see stars in Fig. 5d). This result confirms the role of maximum S states in N = 3 subspace in enhancing the CO instability. This type of interpretation should be valid in large U and J/U limit. Figure 5d shows, however, deviations of actual GW+EDMFT results at J/U = 0.1 and J/U = 0.15. This can be attributed to the non-negligible amount of smaller S states in N = 3 subspace and the fundamental inadequacy of this kind of approach for the FL regime.

In conclusion, we have shown by employing GW+EDMFT that, in the spin-freezing regime, significant enhancement of d3 + d1 CO instability appears. This enhancement is found to be closely related to the local multiplet population profile: maximum spin states are dominant in each total charge subspace with substantial amount of N = 1 and N = 3 occupations. The observed d3 + d1 CO transition is driven by V and is also a distinctive route from the anisotropic orbital-multipole scattering mechanism to the valence-skipping phenomena28. Our study unveils another feature of the Hund’s metal and has potential implications for other multiorbital systems and observed CO in Hund’s metal AFe2As2 (A = Rb, K, Cs)35,36,37.

Methods

GW+EDMFT is derivable from the Ψ[G, W] functional (G: Green’s function, W: fully screened Coulomb interaction)44 as \({\Psi }^{GW+{\rm{EDMFT}}}[G,W]={\Psi }^{\rm{EDMFT}}[{G}_{\rm{loc}},{W}_{\rm{loc}}]\,+{\Psi }_{\rm{nonloc}}^{GW}[G,W]\), where EDMFT is supplemented with nonlocal GW functional45,46,47,48,49. This approach allows a nonperturbative solution of the auxiliary impurity model with self-consistently determined local fermionic and bosonic Weiss fields. The bosonic Weiss field \({\mathcal{U}}(i{\nu }_{n})\) (νn: bosonic Matsubara frequency) is the effective impurity interaction whose value is renormalized by dynamical screening effect. The importance of this effect has recently been highlighted49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. We performed calculations within the paramagnetic isotropic phase and inverse temperature of βD = 100. An impurity model was solved using the COMCTQMC implementation57 of the hybridization–expansion CTQMC algorithm58,59. Both local and nonlocal interaction terms were decoupled via Hubbard–Stratonovich transformation to treat them on an equal footing49. In our current implementation, owing to the computational complexity, we measured only the density–density type of two-particle correlation functions from the impurity; \({\chi }_{{\rm{imp}}}(\tau )=\langle {{\mathcal{T}}}_{\tau }{n}_{\gamma \sigma }(\tau ){n}_{\gamma ^{\prime} \sigma ^{\prime} }(0)\rangle\) (τ: imaginary time). The non-density–density-type functions are responsible for the screening of non-monopole terms of charge distribution, making our approximation physically reasonable since these terms are ill-screened55. All three methods (GW+EDMFT, EDMFT, and GW) were performed self-consistently. See Supplementary Note 2 for further details of our GW+EDMFT calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer code used for this study is available upon reasonable request.

References

de’ Medici, L., Mravlje, J. & Georges, A. Janus-faced influence of Hund’s rule coupling in strongly correlated materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 256401 (2011).

de’ Medici, L. Hund’s coupling and its key role in tuning multiorbital correlations. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205112 (2011).

Georges, A., de Medici, L. & Mravlje, J. Strong correlations from Hund’s coupling. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 137–178 (2013).

Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Coherence-incoherence crossover in the normal state of iron oxypnictides and importance of Hund’s rule coupling. New J. Phys. 11, 025021 (2009).

Yin, Z., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Kinetic frustration and the nature of the magnetic and paramagnetic states in iron pnictides and iron chalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 10, 932–935 (2011).

Fanfarillo, L. & Bascones, E. Electronic correlations in Hund metals. Phys. Rev. B 92, 075136 (2015).

Stadler, K., Kotliar, G., Weichselbaum, A. & von Delft, J. Hundness versus Mottness in a three-band Hubbard-Hund model: on the origin of strong correlations in Hund metals. Ann. Phys. 405, 365–409 (2019).

Werner, P., Gull, E., Troyer, M. & Millis, A. J. Spin freezing transition and non-Fermi-liquid self-energy in a three-orbital model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 166405 (2008).

Nomura, Y., Sakai, S. & Arita, R. Nonlocal correlations induced by Hund’s coupling: a cluster DMFT study. Phys. Rev. B 91, 235107 (2015).

Yin, Z. P., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Fractional power-law behavior and its origin in iron-chalcogenide and ruthenate superconductors: insights from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 86, 195141 (2012).

Horvat, A., Žitko, R. & Mravlje, J. Low-energy physics of three-orbital impurity model with Kanamori interaction. Phys. Rev. B 94, 165140 (2016).

Aron, C. & Kotliar, G. Analytic theory of Hund’s metals: a renormalization group perspective. Phys. Rev. B 91, 041110 (2015).

Horvat, A., Zitko, R. & Mravlje, J. Non-Fermi-liquid fixed point in multi-orbital Kondo impurity model relevant for Hund’s metals. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.07100 (2019).

Deng, X. et al. Signatures of Mottness and Hundness in archetypal correlated metals. Nat. Commun. 10, 2721 (2019).

de’ Medici, L. Hund’s induced Fermi-liquid instabilities and enhanced quasiparticle interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 167003 (2017).

Villar Arribi, P. & de’ Medici, L. Hund-enhanced electronic compressibility in FeSe and its correlation with Tc. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 197001 (2018).

Bascones, E., Valenzuela, B. & Calderón, M. J. Orbital differentiation and the role of orbital ordering in the magnetic state of Fe superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 86, 174508 (2012).

Lanatà, N. et al. Orbital selectivity in Hund’s metals: the iron chalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 87, 045122 (2013).

de’ Medici, L., Giovannetti, G. & Capone, M. Selective Mott physics as a key to iron superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 177001 (2014).

Kostin, A. et al. Imaging orbital-selective quasiparticles in the Hundas metal state of FeSe. Nat. Mater. 17, 869–874 (2018).

Hansmann, P. et al. Dichotomy between large local and small ordered magnetic moments in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 197002 (2010).

Yin, Z., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Magnetism and charge dynamics in iron pnictides. Nat. Phys. 7, 294–297 (2011).

Fanfarillo, L., Giovannetti, G., Capone, M. & Bascones, E. Nematicity at the Hund’s metal crossover in iron superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 95, 144511 (2017).

Mravlje, J. et al. Coherence-incoherence crossover and the mass-renormalization puzzles in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 096401 (2011).

Hoshino, S. & Werner, P. Superconductivity from emerging magnetic moments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 247001 (2015).

Mravlje, J. & Georges, A. Thermopower and entropy: lessons from Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 036401 (2016).

Isidori, A. et al. Charge disproportionation, mixed valence, and Janus effect in multiorbital systems: a tale of two insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 186401 (2019).

Strand, H. U. R. Valence-skipping and negative-U in the d-band from repulsive local Coulomb interaction. Phys. Rev. B 90, 155108 (2014).

Varma, C. M. Missing valence states, diamagnetic insulators, and superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2713–2716 (1988).

Harrison, W. A. Valence-skipping compounds as positive-U electronic systems. Phys. Rev. B 74, 245128 (2006).

Anderson, P. W. Model for the electronic structure of amorphous semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 953–955 (1975).

Katayama-Yoshida, H. & Zunger, A. Exchange-correlation-induced negative effective U. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1618–1621 (1985).

Micnas, R., Ranninger, J. & Robaszkiewicz, S. Superconductivity in narrow-band systems with local nonretarded attractive interactions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 113–171 (1990).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179–186 (2015).

Civardi, E., Moroni, M., Babij, M., Bukowski, Z. & Carretta, P. Superconductivity emerging from an electronic phase separation in the charge ordered phase of RbFe2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 217001 (2016).

Wang, P. S. et al. Nearly critical spin and charge fluctuations in KFe2As2 observed by high-pressure NMR. Phys. Rev. B 93, 085129 (2016).

Moroni, M. et al. Charge and nematic orders in AFe2As2 (A = Rb, Cs) superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 99, 235147 (2019).

Zhou, S., Kotliar, G. & Wang, Z. Extended Hubbard model of superconductivity driven by charge fluctuations in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 84, 140505(R) (2011).

Yan, X.-Z. Theory of the extended Hubbard model at half filling. Phys. Rev. B 48, 7140–7147 (1993).

Pawłowski, G. Charge orderings in the atomic limit of the extended Hubbard model. Eur. Phys. J. B 53, 471–479 (2006).

Kapcia, K. J., Robaszkiewicz, S., Capone, M. & Amaricci, A. Doping-driven metal-insulator transitions and charge orderings in the extended Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 95, 125112 (2017).

Kapcia, K. J., Barański, J. & Ptok, A. Diversity of charge orderings in correlated systems. Phys. Rev. E 96, 042104 (2017).

Terletska, H., Chen, T. & Gull, E. Charge ordering and correlation effects in the extended Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 95, 115149 (2017).

Almbladh, C.-O., von Barth, U. & van Leeuwen, R. Variational total energies from Φ- and Ψ- derivable theories. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 13, 535–541 (1999).

Sun, P. & Kotliar, G. Extended dynamical mean-field theory and GW method. Phys. Rev. B 66, 085120 (2002).

Chitra, R. & Kotliar, G. Effective-action approach to strongly correlated fermion systems. Phys. Rev. B 63, 115110 (2001).

Biermann, S., Aryasetiawan, F. & Georges, A. First-principles approach to the electronic structure of strongly correlated systems: combining the GW approximation and dynamical nean-field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 086402 (2003).

Tomczak, J. M., Casula, M., Miyake, T. & Biermann, S. Asymmetry in band widening and quasiparticle lifetimes in SrVO3: competition between screened exchange and local correlations from combined GW and dynamical mean-field theory GW + DMFT. Phys. Rev. B 90, 165138 (2014).

Ayral, T., Biermann, S. & Werner, P. Screening and nonlocal correlations in the extended hubbard model from self-consistent combined GW and dynamical mean field theory. Phys. Rev. B 87, 125149 (2013).

Ayral, T., Werner, P. & Biermann, S. Spectral properties of correlated materials: local vertex and nonlocal two-particle correlations from combined GW and dynamical nean field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 226401 (2012).

Hansmann, P., Ayral, T., Vaugier, L., Werner, P. & Biermann, S. Long-range Coulomb interactions in surface systems: a first-principles description within self-consistently combined GW and dynamical mean-field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 166401 (2013).

Huang, L., Ayral, T., Biermann, S. & Werner, P. Extended dynamical mean-field study of the Hubbard model with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. B 90, 195114 (2014).

Ayral, T., Biermann, S., Werner, P. & Boehnke, L. Influence of Fock exchange in combined many-body perturbation and dynamical mean field theory. Phys. Rev. B 95, 245130 (2017).

Boehnke, L., Nilsson, F., Aryasetiawan, F. & Werner, P. When strong correlations become weak: consistent merging of GW and DMFT. Phys. Rev. B 94, 201106(R) (2016).

Nilsson, F., Boehnke, L., Werner, P. & Aryasetiawan, F. Multitier self-consistent GW + EDMFT. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 043803 (2017).

Golež, D., Boehnke, L., Strand, H. U. R., Eckstein, M. & Werner, P. Nonequilibrium GW + EDMFT: antiscreening and inverted populations from nonlocal correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 246402 (2017).

Choi, S., Semon, P., Kang, B., Kutepov, A. & Kotliar, G. ComDMFT: a massively parallel computer package for the electronic structure of correlated-electron systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 244, 277–294 (2019).

Gull, E. et al. Continuous-time Monte Carlo methods for quantum impurity models. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 349–404 (2011).

Werner, P. & Millis, A. J. Dynamical screening in correlated electron materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 146401 (2010).

Acknowledgements

S.R. thanks T. Ayral and J.-H. Sim for useful conversation at the early stage of this work. S.R. and M.J.H. were supported by BK21plus program, Basic Science Research Program (2018R1A2B2005204) and Creative Materials Discovery Program through NRF (2018M3D1A1058754). P.S. and S.C. were supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences as a part of the Computational Materials Science Program. This research used resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. conceived the project. S.R. developed the code on top of quantum impurity solver built by P.S. S.R. performed all calculations. S.C., S.R., and M.J.H. discussed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the document.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryee, S., Sémon, P., Han, M.J. et al. Nonlocal Coulomb interaction and spin-freezing crossover as a route to valence-skipping charge order. npj Quantum Mater. 5, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-0221-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-0221-9

This article is cited by

-

Infinite-layer nickelates as Ni-eg Hund’s metals

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Fe3GeTe2: a site-differentiated Hund metal

npj Computational Materials (2022)