Abstract

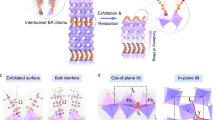

Rotation of MO6 (M = transition metal) octahedra is a key determinant of the physical properties of perovskite materials. Therefore, tuning physical properties, one of the most important goals in condensed matter research, may be accomplished by controlling octahedral rotation (OR). In this study, it is demonstrated that OR can be driven by an electric field in Sr2RuO4. Rotated octahedra in the surface layer of Sr2RuO4 are restored to the unrotated bulk structure upon dosing the surface with K. Theoretical investigation shows that OR in Sr2RuO4 originates from the surface electric field, which can be tuned via the screening effect of the overlaid K layer. This work establishes not only that variation in the OR angle can be induced by an electric field, but also provides a way to control OR, which is an important step toward in situ control of the physical properties of perovskite oxides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskite materials possess some of the most interesting properties in condensed matter physics, such as superconductivity, metal–insulator transitions, and ferroicity1. Theoretical and experimental research has proven that octahedral rotation (OR) plays an important role in those properties. For instance, OR significantly affects metal–insulator transitions2,3 and exotic orbital-selective phenomena4,5 by changing the inter-site electron hopping probability and even the structural symmetry of materials. Furthermore, the magnetic ground state of a material is often governed by OR through altered super-exchange or Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions6. Therefore, the ability to readily vary OR would be an important step toward controlling such physical properties.

However, in spite of its importance, there are a limited number of reports on controlling OR7,8,9. The main reason for this is that the OR angle is thought to be an inherent characteristic of a material, determined by the steric effect arising from the sizes of its constituent atoms10,11. Thus, most of the attempts to control OR have been limited to substitution of atoms with different ionic sizes or application of strains using different substrates. However, these methods do not truly allow control of the OR angle as they cannot be applied in situ, and typically cause complex side effects12,13.

When attempting to control physical properties through the OR angle, various parameters should be considered, such as pressure and magnetic and electric fields. Among these parameters, the electric field has distinct advantages in terms of convenience, controllability, and minimal power consumption. In this letter, we report electric-field-dependent evolution of the OR angle on the surface of Sr2RuO4. By means of in situ dosing with potassium (K), the surface electric field can be tuned through the screening effect of the overlying K atoms. Sr2RuO4 was chosen as the target material given its distinct surface layer-driven bands, which arise due to differences in its structural symmetry (a finite OR angle at its surface and no rotation of its bulk)14,15,16; these properties not only provide clean surfaces, but also make investigation of its electronic structure relatively easy. Our results obtained using the surface-sensitive techniques of low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) and angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy (ARPES) indicate that reduction of the electric field results in a reduced OR angle (down to zero). Our density functional theory (DFT) studies have shown that the surface electric potential (or surface electric field)17,18 is responsible for the OR on the surface of Sr2RuO4, which in turn implies the possibility of controlling the OR angle via an electric field.

Results

Disappearance of Sr2RuO4 surface states upon K coverage

Figure 1 shows Fermi surface (FS) maps of freshly cleaved and K-dosed Sr2RuO4 surfaces. The main features are two bulk electron pockets (βb and γb) centered at Γ and a bulk hole pocket (αb) centered at (π,π). In addition to these bulk FSs, we detected additional FSs from the surface (αs, βs, γs) and zone-folded surface (αsf, βsf, γsf) bands (Fig. 1a), consistent with previously reported ARPES results15,16,19. Notably, when we deposit K on the surface with coverage above one monolayer (ML), all of the surface-related FSs disappear (Fig. 1b), which is somewhat similar to the case of surface aging of Sr2RuO4 (refs. 16,19). To deduce the reason for this disappearance, we systematically varied the coverage of K while conducting LEED and ARPES measurements.

a Fresh Sr2RuO4 and b Sr2RuO4 covered in two monolayers (MLs) of K. The black thick (thin) dashed lines mark the Brillouin zone of the bulk (surface) Sr2RuO4 without (with) octahedral rotation. RuO6 octahedra on the surface rotate, resulting in a \(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\) reconstructed surface that causes replica FSs to appear. Superscripts b, s, sf, and ov denote bulk, surface, surface folding, and overlap, respectively. The blue (red) guidelines indicate the bulk (surface) bands. Kqw indicates a K circular quantum well state (Supplementary Fig. 4).

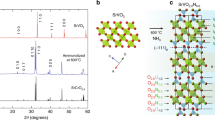

LEED is one of the most direct and convenient methods to investigate in-plane crystal symmetry. In case when there is no OR distortion, only the 1 × 1 peak should appear. When the in-plane OR angle is finite, the unit cell is transformed to a \(\left( {\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2 } \right)R45^\circ\) unit cell, and consequently additional fractional peaks (\(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\)) should appear in the LEED pattern. The relative intensity of the fractional to integer spot is approximately proportional to the OR angle20,21. The LEED results from our systematic investigation of K coverage are shown in Fig. 2a. In the LEED data of pristine Sr2RuO4, we can observe both 1 × 1 and \(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\) peaks. As the K coverage increases, the OR-driven \(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\) peaks gradually weaken and eventually disappear above 1 ML of K, while the 1 × 1 peaks remain robust. Therefore, we suspect that the K layer gradually and eventually completely suppresses the OR of the surface Sr2RuO4.

a Electron diffraction images for various K coverages (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 ML). The yellow arrows indicate peaks due to \(\sqrt 2 \times \sqrt 2\) surface reconstruction; as the K coverage increases, these peaks gradually become weaker and eventually disappear. The rectangle in red is the region of quantitative intensity analysis in Supplementary Fig. 1. b Photoelectron spectroscopy images along Γ–M–Γ for various K coverages (0, 0.17, 0.34, 0.5, 0.67, 0.83, and 1 ML). Red dashed lines are to mark the position of βb of 0 ML coverage.

The ARPES results from our systematic investigation of K coverage are shown in Fig. 2b; they also provide evidence for the suppression of OR in the surface Sr2RuO4. The data for pristine Sr2RuO4 along Γ–M–Γ (Fig. 2b) show βb, βs, γb, and γs bands. As the K coverage increases, the βs band, instead of being suppressed, moves toward βb before finally merging with it. As for the γ bands, γb remains the same while the spectral weight of the γs band at the M-point gradually weakens. These observations indicate that the difference between the bulk and surface electronic structures gradually decreased, consistent with the suppression of OR in the surface layer. Our detailed analysis regarding the ARPES spectra (Supplementary Fig. 1) also supports that the suppression of the surface layer-driven bands is induced by suppression of the surface OR.

Cause of the suppressed OR

The next question is why the OR angle reduces with K-dosing. Surface alkali metal atoms can play roles in electron doping, chemical bonding, and changing the surface electric potential; we shall consider each in turn. First, we consider the possibility that the vanishing OR is caused by electron transfer from the alkali metal to the Sr2RuO4. To investigate this, we obtained the electron occupations of the bands from their FS volume; we list these in the Supplementary Table 1 along with all other values discussed here. We find that there is an occupation difference of 0.09 electrons between the fresh surface (3.82) and that with 1 ML of K (3.91), which agrees well with the number (0.07) extracted from our theoretical study (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, an average transfer of 0.09 electrons from the K atoms is not likely to cause complete suppression of OR considering the case of (Sr,La)2RuO4, which is regarded as electron-doped Sr2RuO4 (Supplementary Fig. 3). On the other hand, effects arising from chemical bonding cannot provide an adequate explanation either; our measured K 3p core-level spectra as a function of K coverage (Supplementary Fig. 4) clearly show the absence of chemical bonding associated with K atoms. Furthermore, as mentioned, our experimental and theoretical results (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2) suggest that there an electron transfer of only 0.07–0.09 from the K atoms, which is too small to be due to chemical bonding between the K and O atoms.

As the change in OR angle cannot be attributed to electron doping or chemical bonding effects, let us now consider the gradient of the surface electric potential. In general, the electric potential is modulated due to the electric potential difference between vacuum and solid. This electric potential modulation is greatly affected by the surface condition, as illustrated in Fig. 3a and b. To investigate how electric potential relates to the OR angle, we performed a DFT calculation which has been widely used to describe low-energy physics in Sr2RuO4 (refs. 15,16,22), by constructing a five-layer slab of Sr2RuO4 with and without an ML of K overlaid. We also performed calculations for various K-layer distances away from the equilibrium position, to investigate the evolution of the electric potential and OR angle.

a Crystal structure of Sr2RuO4 with three different K coverages (left: fresh, middle: partial coverage, right: 1 ML). The dashed rectangle marks the area for the enlarged view in Fig. 4a. b–d Density functional theory (DFT) results for a slab of Sr2RuO4 five layers thick. b Electric potential energy as a function of the depth in the c-direction (surface normal), for various K-layer distances from the equilibrium position: d = 0.0, 0.6, 1.2 Å and without a K layer. The equilibrium position of the surface K layer (9.4 Å from the second outermost Ru–O layer) was obtained from the DFT calculation. The gray horizontal dashed line indicates the electric potential energy in the Sr2RuO4 interlayer region. As the K-layer distance decreases, the electric potential in the SrO–K region gradually decreases toward the value of the interlayer region (black arrow). c Plot of OR angle as a function of the K-layer distance from the equilibrium position. d Plot of OR angle as a function of electric field.

First, we note that the potential energy decreases gradually toward the value of the interlayer region as the K layer approaches the equilibrium position (the arrow in Fig. 3b). This suggests that the role of the K layer is to mitigate the surface electric field; 1 ML of K causes the electric potential in the surface region to become similar to the interlayer potential. Consequently, the surface layer is in a bulk-like potential, which should lead to the suppression of OR (Fig. 3a). The calculated OR angle monotonically evolves from zero to fully rotated as the K-layer distance increases from the equilibrium position (Fig. 3c). These observations strongly indicate that the origin of the OR is in the electric field, consistent with the experimental data in Fig. 2.

Even though it is not essential to prove the electric origin of the OR, it is noteworthy that the OR evolution in the calculation in Fig. 3c fairly consistently reproduces the behavior according to the thickness of the K layer seen in the experimental data. Partial K-coverage cases have been simulated by artificially moving the K layer away from the equilibrium position23. The similarity between the experimental and theoretical results may be understood in the following way. Figure 3b shows the calculated electric potential as a function of the K-layer distance from surface layer. The electric potential at the interface (between the outermost SrO layer and the K layer) monotonically and gradually changes as the K-layer distance changes. We expect that the surface electric field will be screened by K atoms proportionally with the K coverage (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the ‘moving K-layer distance’ should generate similar trends in the electric potential as does the K coverage. Our electronic structure with ‘moving K-layer distance’ does indeed show trends consistent with our K-coverage-dependent ARPES results (Supplementary Fig. 5); hence, the method should be reasonable to observe the overall trend.

To directly investigate the role of the electric field in the OR angle, we performed another five-layer slab calculation, this time with an external electric field applied perpendicular to the surface (Fig. 3d). Our DFT calculations of total energy predict that the surface OR changes, exhibiting behavior proportional to the increase of ~0.15° per 0.1 V Å−1 (Fig. 3d); thus, the electric field appears to be coupled to the OR. Therefore, we conclude that the electric field is responsible for the OR in the Sr2RuO4 surface layer and thus the OR can be varied by tuning the electric potential.

Mechanism of the electric-field-driven OR

The next step is to find out how an electric field couples with the OR. Previous theoretical studies have shown that ferroelectric-like atomic displacement competes with the OR, which is the reason why most of ferroelectric materials do not have OR distortion24. Therefore, it is natural to consider non-uniform atomic displacements driven by depth-dependent electric field as the cause for the OR angle change. From our DFT calculation with K-layer distance variation, we extract atomic displacement in the outermost Sr–O layer. It shows that the distance between upper and lower Sr atoms in the surface Sr2RuO4 layer is the most sensitive factor to the K-layer distance (Supplementary Fig. 6). It is found that the vertical Sr–Sr distance (defined in Fig. 3a) increases with the electric field (K-layer distance) and changes more than 0.1 Å as shown in Fig. 4a.

a DFT calculation results from a five-Sr2RuO4-layer slab. The plot shows the Sr–Sr distance as a function of the K-layer distance. Inset: enlarged view of an octahedron in the surface Sr2RuO4 layer. Sr–Sr distance (dSr) is defined as the vertical distance between upper and lower Sr atoms. b DFT results for the OR angle as a function of the Sr–Sr distance for bulk Sr2RuO4, Sr2RhO4, and Sr2IrO4. The shaded region marks the actual range over which the Sr–Sr distance varies in a.

In order to check whether the (vertical) Sr–Sr distance is coupled to the OR angle variation, we have estimated OR angle from bulk Sr2RuO4 calculation as a function of the Sr–Sr distance (Fig. 4b). As can be seen in Fig. 4b, variation of the Sr–Sr distance successfully reproduces emergence of the OR angle in Sr2RuO4 in the range over which the Sr–Sr distance varies in Fig. 4a. Therefore, it appears that the Sr–Sr distance is the mediating parameter between the surface electric field and OR angle. As the stronger (weaker) surface electric field makes a larger (smaller) Sr–Sr distance, and it eventually leads to a larger (smaller) OR angle. In this context, we can reconsider how OR varies depending on the situation in Sr2RuO4. Absence of surface electric potential makes octahedron unrotated in bulk Sr2RuO4. On the other hand, the surface layer feels the surface electric potential, and thus the (surface electric potential driven) large Sr–Sr distance makes octahedron rotated in the surface layer. Upon K dosing, the K atoms gradually reduce the surface electric potential toward the value of bulk electric potential. Then, the OR angle in the surface layer gradually decreases down to zero as we observed.

This mechanism can be applied to various materials other than Sr2RuO4. We performed additional bulk calculation on Sr2RhO4 and Sr2IrO4 for various Sr–Sr distances (Fig. 4b), and it is found that OR angles of Sr2RhO4 and Sr2IrO4 are affected by Sr–Sr distance in the same manner as in the case of Sr2RuO4, even though the large initial OR angles of Sr2RhO4 and Sr2IrO4 make their variation less dramatic. These results not only consistently simulate the OR angle variation behavior in K-dosed Sr2RuO4, but also suggest that there might be universal coupling between the OR angle and cation distance in transition-metal oxide (TMO).

Discussion

We shall now discuss the difference between the local and external electric fields to allow our result to be more fully understood. Even though we theoretically demonstrated an OR angle change by an external electric field (Fig. 3d), ~4 V Å−1 is required for full suppression of the OR, which is not practical. However, a local electric field (potential gradient near the surface) can induce full suppression of the OR in Sr2RuO4, as shown in Fig. 3b, where varying the K-layer distance changes the electric potential energy on the order of a few eV. This case demonstrates the advantages of exploiting the local electric field, in terms of strength and controllability. In practice, such local electric fields could be achieved by using special techniques such as ionic gating or even exploiting existing, naturally occurring fields at interfaces. In that respect, issues in groups of material heterostructures, which exhibit numerous exotic phenomena that the corresponding bulk crystals do not, such as superconductivity25,26, metal–insulator transitions27, and controllable ferromagnetism could be revisited28. We suspect that local electric fields at interfaces play a significant role in generating these phenomena, and our findings should provide important clues regarding their microscopic mechanisms.

Since OR is not a polar distortion, whereas an electric field would produce a polar distortion, an electric field effect has rarely been considered when determining the OR angle. In this regard, the discovery of hybrid improper ferroelectricity (HIF) was a surprise because it shows an unexpected coupling between OR and ferroelectric (polar) distortion of Ca atom (A-atom in A3B2O7) in double-layer perovskites such as Ca3Ti2O7 (refs. 29,30). Some theoretical studies have proposed electrical control of physical properties by changing the OR angle via the HIF mechanism31,32, but this has not yet been achieved experimentally. Contrary to the case of HIF, Sr2RuO4 is a metal and normally is not a suitable candidate for ferroelectric distortion. However, a finite displacement for Sr atom (A-atom in A2BO4) in the surface Sr2RuO4 layer can be induced by the surface electric potential, and then the Sr displacement may establish the connection between electric field and OR (Fig. 4). Note that A-atom mediates electric field and OR in both HIF and surface Sr2RuO4 cases, which may imply a possible universal mechanism of OR angle variation via A-atom modulation. Our work not only is to show a change in OR angle via electric field, but also may initiate follow-up studies to elucidate the mechanism of OR angle variation.

Finally, let us discuss possible effects of OR angle variation in systems with strong electron correlation since perovskite oxides are typically in the strong electron correlation regime. Since OR angle can significantly affect the exchange interaction as well as electron localization, it is expected that change in the OR angle can lead to various phenomena, e.g., magnetism and metal–insulator transitions. Such effects may be found in the case of Ca2-xSrxRuO4 (CSRO) which may be viewed as Sr2RuO4 with OR angle variation. In CSRO, rich and complex phases33,34,35, such as magnetisms (ferromagnetism33 or antiferromagnetism34), appear and emergence of those phenomena are attributed to OR distortions5,36,37. Another important aspect is that the electronic structure of Sr2RuO4 possesses a van Hove singularity near the Fermi level whose position is very sensitive to the OR angle. The large density of states from the van Hove singularity can boost the instability from electron correlation. This implies that we could effectively control the electron correlation strength of the system via the OR angle. Control of OR therefore may allow us a more diverse controllability of physical properties in strongly correlated materials.

In conclusion, our experimental and theoretical investigations demonstrate that variation of electric potential is responsible for the OR angle in the Sr2RuO4 surface layer, and that OR angle can be varied by tuning the electric potential through surface K dosing. Our result not only sheds light on the mechanism of octahedral distortion found in various oxide systems but is also an important step toward electric field control of physical properties via variation of the OR angle in perovskite oxides.

Methods

ARPES and LEED measurement conditions

ARPES (hν = 70 eV) measurements were performed at beam lines (BLs) 4.0.3 and 7.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, USA. Potassium dosing was carried out by evaporating K onto the sample using commercial alkali metal dispensers (SAES). Spectra were acquired with R8000 (BL 4.0.3) and R4000 (BL 7.0.2) electron analyzers (Scienta). Total energy resolution was set to 12 meV, and the angular resolution was 0.00163 Å−1. Cleaving and dosing of the samples were done at 20 K in an ultra-high vacuum better than 5 × 10−11 Torr. LEED measurements were performed at BL 7.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source and at the Center for Correlated Electron Systems of the Institute for Basic Science, Seoul National University, Republic of Korea, using a LEED spectrometer (SPECS) with an electron energy of 187 eV.

Information of DFT calculation

As the feasibility of using DFT to understand the structural and electronic properties of Sr2RuO4 has been shown through previous studies15,16,22, we performed first-principle calculation using the non-spin-polarized DFT method without spin-orbit coupling. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof form of the exchange-correlation functional was used as implemented in VASP software38,39. We used a 600 eV plane wave cut-off energy and 12 × 12 × 1 k-points for all calculations and the projector augmented wave method. The in-plane lattice constant was fixed at the experimental value of Sr2RuO4. All the internal atomic positions were fully relaxed until the maximum force was below 0.5 meV Å−1 while the symmetries of the system (point group D4h) were maintained during the relaxation. In practice, since full relaxation is numerically unstable, we fixed the rotation angle of the octahedron and relaxed only the vertical positions of the atoms of the surface. In this way, the energy curve as a function rotation angle was obtained, and the angle with the energy minimum was found. We also checked that no additional symmetry lowering occurs even without symmetry constraints for a few cases. To mimic partial K coverage, we performed a five-layer slab calculation with 15 Å vacuum layer, which is symmetric with respect to the middle layer with an overlying K atom layer. In this calculation, we relaxed the distance between the K layer and the Sr2RuO4 to find the equilibrium K-layer position. The resultant value was the ‘K EQ position’ in Fig. 3 (9.4 Å−1 from the second Ru–O layer). In the calculation, we relaxed both the outermost layer and the K-layer distance, which explains why we defined the position relative to the second Ru–O layer. The location of each K atom could not be specified experimentally, so we assumed it to be above the apical oxygen atom of the outermost Sr–O layer (as illustrated in Fig. 3a) since that is the energetically most stable position in our DFT calculation. For the bulk calculations of Sr2RhO4 and Sr2IrO4, the in-plane lattice constants were also fixed as the experimental lattice constant of each compound, 5.4516 and 5.4956 Å, respectively. In these calculations, we fixed the Sr and Ir positions and allowed to move oxygen atoms only to find the optimum rotation angle of the octahedron for a given Sr–Sr distance.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Rao, C. N. R. Transition metal oxides. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 40, 291–326 (1989).

Balachandran, P. V. & Rondinelli, J. M. Interplay of octahedral rotations and breathing distortions in charge-ordering perovskite oxides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054101 (2013).

Nie, Y. F. et al. Interplay of spin-orbit interactions, dimensionality, and octahedral rotations in semimetallic SrIrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 016401 (2015).

Kim, B. J. et al. Missing xy-band Fermi surface in 4d transition-metal oxide Sr2RhO4: effect of the octahedra rotation on the electronic structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 106401 (2006).

Ko, E., Kim, B. J., Kim, C. & Choi, H. J. Strong orbital-dependent d-band hybridization and Fermi-surface reconstruction in metallic Ca2−xSrxRuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 226401 (2007).

Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 4, 241–255 (1958).

Lu, W. et al. Control of oxygen octahedral rotations and physical properties in SrRuO3 films. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214115 (2013).

May, S. J. et al. Control of octahedral rotations in (LaNiO3)n/(SrMnO3)m superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 83, 153411 (2011).

Gao, R. et al. Interfacial octahedral rotation mismatch control of the symmetry and properties of SrRuO3. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 14871–14878 (2016).

Megaw, H. D. A simple theory of the off-centre displacement of cations in octahedral environments. Acta Crystallogr. B B24, 149–153 (1968).

Brown, I. D. Chemical and steric constraints in inorganic solids. Acta Crystallogr. B B48, 553–572 (1992).

Cheng, S. L., Du, C. H., Chuang, T. H. & Lin, J. G. Atomic replacement effects on the band structure of doped perovskite thin films. Sci. Rep. 9, 7828 (2019).

Steppke, A. et al. Strong peak in Tc of Sr2RuO4 under uniaxial pressure. Science 355, eaaf9398 (2017).

Matzdorf, R. et al. Ferromagnetism stabilized by lattice distortion at the surface of the p-wave superconductor Sr2RuO4. Science 289, 746–748 (2000).

Damascelli, A. et al. Fermi surface, surface states, and surface reconstruction in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 5194 (2000).

Veenstra, C. N. et al. Determining the surface-to-bulk progression in the normal-state electronic structure of Sr2RuO4 by angle-resolved photoemission and density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 097004 (2013).

Ishikawa, K. & Uemori, T. Surface relaxation in ferroelectric perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 60, 11841 (1999).

Barnes, S. E., Ieda, J. & Maekawa, S. Rashba spin-orbit anisotropy and the electric field control of magnetism. Sci. Rep. 4, 4105 (2014).

Zabolotnyy, V. B. et al. Surface and bulk electronic structure of the unconventional superconductor Sr2RuO4: unusual splitting of the β band. N. J. Phys. 14, 063039 (2012).

Hu, B. et al. Surface and bulk structural properties of single-crystalline Sr3Ru2O7. Phys. Rev. B 81, 184104 (2010).

Li, G. et al. Atomic-scale fingerprint of Mn dopant at the surface of Sr3(Ru1−xMnx)2O7. Sci. Rep. 3, 2882 (2013).

Veenstra, C. N. et al. Spin-orbital entanglement and the breakdown of singlets and triplets in Sr2RuO4 revealed by spin- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 127002 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Observation of tunable band gap and anisotropic Dirac semimetal state in black phosphorus. Science 349, 723–726 (2015).

Benedek, N. A. & Fennie, C. J. Why are there so few perovskite ferroelectrics? J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 13339–13349 (2013).

Reyren, N. et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science 317, 1196–1199 (2007).

Aird, A. & Salje, E. K. H. Sheet superconductivity in twin walls: experimental evidence of WO3-x. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 10, L377–L380 (1998).

Meyers, D. et al. Pure electronic metal-insulator transition at the interface of complex oxides. Sci. Rep. 6, 27934 (2016).

Heron, J. T. et al. Electric-field-induced magnetization reversal in a ferromagnet-multiferroic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217202 (2011).

Benedek, N. A. & Fennie, C. J. Hybrid improper ferroelectricity: a mechanism for controllable polarization-magnetization coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107204 (2011).

Oh, Y. S. et al. Experimental demonstration of hybrid improper ferroelectricity and the presence of abundant charged walls in (Ca,Sr)3Ti2O7 crystals. Nat. Mater. 14, 407–413 (2015).

Benedek, N. A., Mulder, A. T. & Fennie, C. J. Polar octahedral rotations: a path to new multifunctional materials. J. Solid State Chem. 195, 11–20 (2012).

Liu, X. Q. et al. Hybrid improper ferroelectricity and possible ferroelectric switching paths in Sr3Hf2O7. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 114105 (2019).

Nakatsuji, S. et al. Heavy-mass Fermi liquid near a ferromagnetic instability in layered ruthenates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 137202 (2003).

Carlo, J. P. et al. New magnetic phase diagram of (Sr,Ca)2RuO4. Nat. Mater. 11, 323–328 (2012).

Gorelov, E. et al. Nature of the Mott Transition in Ca2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 226401 (2010).

Noh, H.-J. et al. Electronic structure and evolution of the orbital state in metallic Ca2−xSrxRuO4. Phys. Rev. B 72, 052411 (2005).

Neupane, M. et al. Observation of a novel orbital selective Mott transition in Ca1.8Sr0.2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 097001 (2009).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to E. A. Kim and S. Y. Park for fruitful discussions. This work was supported by the Institute for Basic Science in Korea (Grant No. IBS-R009-G2). The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.K. conceived the work. W.K., Y.K.K., B.K., and C.K. (Chul Kim) performed ARPES measurements with the support from J.D.D., and W.K. and Y.K.K. analyzed the data. W.K., W.J., J.K., and M.K. performed the LEED measurement with support from A.B. Samples were grown and characterized by Y.Y.. C.H.K. led the theoretical study and performed the DFT calculation. All authors discussed the results. W.K. and C.K. (Changyoung Kim) led the project and manuscript preparation with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyung, W., Kim, C.H., Kim, Y.K. et al. Electric-field-driven octahedral rotation in perovskite. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00306-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00306-1

This article is cited by

-

Multifaceted impact of Ni-ion doping on the structural, electronic, magnetic, and optical properties of CoScO3 compounds: a first-principles study

Indian Journal of Physics (2024)

-

Orbital-selective metal skin induced by alkali-metal-dosing Mott-insulating Ca2RuO4

Communications Physics (2023)