Abstract

Atomic manipulation and interface engineering techniques have provided an intriguing approach to custom-designing topological superconductors and the ensuing Majorana zero modes, representing a paradigm for the realization of topological quantum computing and topology-based devices. Magnet-superconductor hybrid (MSH) systems have proven to be experimentally suitable to engineer topological superconductivity through the control of both the complex structure of its magnetic layer and the interface properties of the superconducting surface. Here, we demonstrate that two-dimensional MSH systems containing a magnetic skyrmion lattice provide an unprecedented ability to control the emergence of topological phases. By changing the skyrmion radius, which can be achieved experimentally through an external magnetic field, one can tune between different topological superconducting phases, allowing one to explore their unique properties and the transitions between them. In these MSH systems, Josephson scanning tunneling spectroscopy spatially visualizes one of the most crucial aspects underlying the emergence of topological superconductivity, the spatial structure of the induced spin–triplet correlations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to create, control, and manipulate topological superconducting phases is quintessential for the realization of topological quantum computing using the non-Abelian braiding statistics of Majorana zero modes1. These modes have been observed in one-2,3,4,5,6,7 and two-dimensional (2D) topological superconductors8,9,10, with the latter also exhibiting chiral Majorana edge modes11,12,13. Magnet-superconductor hybrid (MSH) systems consisting of chains, islands, or layers of magnetic adatoms deposited on the surface of conventional s-wave superconductors have proven to be suitable experimental systems for (a) the creation of topological superconductivity using atomic manipulation6 or interface engineering techniques12 and (b) the study of Majorana modes using scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS). In particular, 2D MSH systems, with their topological invariant given by the Chern number, are predicted to exhibit a rich topological phase diagram14,15,16. However, the experimental ability to tune between different topological phases in 2D MSH systems, essential for exploring the nature of topological superconductivity, has not yet been realized.

In the following, we demonstrate that the ability to tune between topological phases can be achieved in 2D MSH systems containing a magnetic skyrmion lattice by varying the skyrmion radius. As the latter can be experimentally controlled through the application of an external magnetic field17, the skyrmion MSH system presents an unprecedented opportunity to explore a rich phase diagram of topological superconducting phases, and the transitions between them. The underlying origin for the ability to control the topological phases lies in a spatially inhomogeneous Rashba spin–orbit (RSO) interaction that is induced by the magnetic skyrmion lattice. The induced RSO interaction images the local topological skyrmion charge—the skyrmion number density—and possesses a characteristic spatial signature in the zero-energy local density of states (LDOS), which can be observed at a topological phase transition as well as in the LDOS of chiral Majorana edge modes. Finally, we demonstrate that Josephson STS (JSTS) can be employed to visualize one of the most fundamental aspects underlying the emergence of topological superconductivity, the existence of induced spin–triplet superconducting correlations. As 2D skyrmion MSH systems can be built with currently available experimental techniques, our results open unexplored venues for the investigation and manipulation of topological superconductivity and Majorana zero modes.

Results

Theoretical model

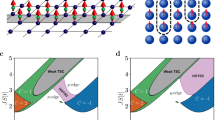

We investigate the emergence of topological superconductivity in a 2D MSH system, in which a magnetic skyrmion lattice (see Fig. 1a) is placed on the surface of a conventional s-wave superconductor, as described by the Hamiltonian

where \({c}_{{\bf{r}}\alpha }^{\dagger}\) creates an electron at lattice site r with spin α, and σ is the vector of spin Pauli matrices. We consider a triangular lattice with lattice constant a0, chemical potential μ, and hopping amplitude \(-{t}_{{\bf{rr}}^\prime}=-{t}\) between nearest-neighbor sites only. Δ is the superconducting s-wave order parameter. The spatial spin structure of the skyrmion lattice is encoded in Sr (see Supplementary Note 1), which represents the direction of an adatom’s spin located at site r, and J is its exchange coupling with the conduction electron spin. Note that the creation of Majorana modes in single skyrmions has previously been discussed in refs. 18,19. As Kondo screening is suppressed by the full superconducting gap, the spins Sr are taken to be classical vectors of length S. We assume that the triangular lattice of skyrmions is commensurate with the underlying triangular surface lattice, thus allowing the skyrmion radius R to take integer and half-integer values of a0. Note that in contrast to earlier studies of 2D MSH systems14,15,16, the above Hamiltonian does not contain an intrinsic RSO interaction. Moreover, due to the broken time-reversal symmetry arising from the presence of magnetic moments, and the particle–hole symmetry of the superconducting state, the topological superconductor belongs to class D20.

To characterize the topological superconducting phases of the system, we compute the topological invariant – the Chern number C – given by

where En(k) and \(\left|{\Psi }_{n}({\bf{k}})\right\rangle\) are the eigenenergies and the eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1), respectively, with n being a band index, and the trace is taken over Nambu and spin-space. Further insight into the origin underlying the emergence of topological superconductivity in skyrmion MSH systems can be gained by considering the spatial structure of the skyrmion and Chern number densities, ns(r) and C(r), respectively. The former is given by

yielding a skyrmion number ns = ∑r ns(r). The latter, C(r)21,22 (see Supplementary Note 2), represents the real-space analog of the Berry curvature, and allows a real-space calculation of the Chern number23,24 C = 1/N2∑rC(r) that coincides with that obtained from Eq. (2).

Topological phase diagram

A crucial aspect for the emergence of topological superconductivity in 2D skyrmion MSH systems is that the magnetic skyrmion lattice induces an effective, spatially varying RSO interaction. To demonstrate this, we apply a unitary transformation25 to the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) (see Supplementary Note 2) that rotates the local spin Sr to the \(\hat{z}\) axis, yielding an out-of-plane ferromagnetic order and a spatially inhomogeneous RSO interaction, α(r) (see Fig. 1b). α(r) possesses the same spatial structure as the skyrmion number density, ns(r) (see Fig. 1c) – reflecting its origin in the local topological charge of the skyrmon lattice – with its largest value, \({\alpha }_{\max }=\pi {a}_{{\rm{0}}}t/(2R)\), in the center of the skyrmion, and a vanishing α(r) at the corners of the skyrmion lattice Wigner–Seitz unit cell. The existence of a non-zero α(r), of an out-of-plane ferromagnetic order in the rotated basis, and of a hard s-wave gap, satisfies all necessary requirements for the emergence of topological superconductivity14,15,16, resulting in the rich topological phase diagram shown in Fig. 2.

The phase diagram in the (μ, R) plane (see Fig. 2a) reveals the intriguing result that it is possible to tune a skyrmion MSH system between different topological phases by changing the skyrmion radius R, which can be experimentally achieved through the application of an external magnetic field17. This unprecedented ability arises from the facts that (a) varying the skyrmion radius leads to changes in the induced α(r), and (b) in contrast to MSH systems with a homogeneous ferromagnetic structure, topological phase transitions in magnetically inhomogeneous MSH systems (as given here) are controlled not only by μ and J, but also by α. Indeed, the results in Fig. 2a reveal that the phase transition lines in the (μ, R) plane are determined by μ = Ai + Bi/R2 (see dotted lines) with constants Ai, Bi. Since \({\alpha }_{\max } \sim 1/R\), our result suggests that the induced RSO interaction leads to an effective renormalization of the chemical potential18, thus facilitating the ability to tune between topological phases. This dependence of the phase transition lines on R is also revealed when considering the phase diagrams in the (μ, JS) plane for different skyrmion radii (see Fig. 2b). These phase diagrams show a very similar structure of topological phases for different R, with the phases moving to lower values of μ with increasing R. We note that the topological phases that are accessible through tuning of R strongly depend on JS (see Fig. 2c): for sufficiently large JS, every change in the skyrmion radius by half a lattice constant leads to a change in the system’s Chern number. Thus, a rich topological phase diagram can be accessed and explored through changes in the skyrmion radius R.

The inhomogeneous magnetic structure of the MSH system also allows us to reveal an intriguing connection between the Chern number density, C(r), which is a local marker for the topological nature of the system, and the Berry curvature in momentum space. In particular, the spatial structure of C(r) (see Fig. 1d) reflects that of the skyrmion lattice, but is complementary to that of the induced α(r) (see Fig. 1b), with the maximum in C(r) occurring at the corners of the skyrmion lattice unit cell. However, it is in these regions, where α is the smallest that the lowest energy states possess their largest spectral weight (as spectral weight is pushed to higher energies with increasing α, see discussion below), establishing a real-space analog of the observation that the lowest energy states in momentum space possess the largest Berry curvature.

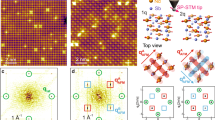

Electronic structure at a topological phase transition

The real-space structure of the induced RSO interaction, and hence that of the local topological skyrmion charge, is reflected in the electronic structure of the MSH system, and becomes particularly evident at a topological phase transition. To demonstrate this, we consider the transition between a C = 8 and C = 6 phase, as indicated by the solid black dot in Fig. 2c. While the system possesses a topological gap on either side of the transition, the gap at the transition closes at the \(K,{K}^{\prime}\)-points (see Fig. 3a), as confirmed by a plot of the dispersion Ek of the lowest energy band (see Fig. 3b) in the reduced Brillouin zone (RBZ). This gap closing is reflected in a unique spatial and energy structure of the zero-energy LDOS [see (xy)-plane in Fig. 3c]. In particular, the spatial structure of the LDOS reveals that the largest (smallest) spectral weight of the zero-energy state, associated with the phase transition, is located where the induced RSO interaction is the smallest (largest), at the corners of the Wigner–Seitz unit cell (the skyrmion center). Thus, the spatial pattern of the zero-energy LDOS is complementary to that of the local topological skyrmion charge, ns(r). Moreover, as the topological gap in general increases with increasing RSO interaction, we find that the large induced RSO interaction in the skyrmion center leads to a dome-like region in energy in which the LDOS is suppressed [see (x, E)- and (y, E)-planes in Fig. 3c]. The electronic structure of the skyrmion MSH systems also provides a unique example to demonstrate that the multiplicity m of the momenta in the Brillouin zone, at which the gap closing occurs, determines and is equal to the change in the Chern number at the transition. For the time-reversal invariant (TRI) \(\Gamma ,M,(K,K^{\prime} )\) points, the multiplicity is m = 1, 3, 2 (note that by symmetry, a gap closing at the K point implies a gap closing at \({K}^{\prime}\) as well), respectively, as each M \((K,{K}^{\prime})\) point is shared by 2 (3) BZs, leading to a change in the Chern number by ΔC = 1, 3, 2 at the transition. Gap closings can also occur at non-TRI points, e.g., at points along the Γ − M line (see Supplementary Note 3), which possess a multiplicity of m = 6, resulting in a change of the Chern number by ΔC = 6. While all of the above gap closings exhibit a Dirac cone (see Fig. 3a), there also exist gap closings that exhibit lines of zero energy (see Supplementary Note 3), rather than discrete zero-energy Dirac points. These gap closings, however, are not accompanied by a change in the Chern number.

a Electronic bands at the phase transition between two topological phases with C = 6 and C = 8 (as indicated by the solid black dot in Fig. 2c) for R = 6a0 and parameters (μ, Δ, JS) = (−5, 0.4, 0.657)t. Shown is the Brillouin zone (BZ) of the skyrmion lattice, i.e., the reduced BZ (RBZ) of the underlying surface lattice. The position of the Dirac point is indicated by an arrow. b Spatial plot of the dispersion Ek of the lowest energy band in the RBZ (as = 2R is the lattice constant of the skyrmion lattice). c Spatial plot of the LDOS at the phase transition, as a function of position and energy.

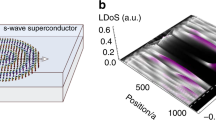

MSH system with a skyrmion ribbon

To study the emergence of chiral Majorana edge modes in a skyrmion MSH system, we next consider a skyrmion ribbon placed on the surface of an s-wave superconductor (see Fig. 4a). In a topological phase with Chern number C, the bulk-boundary correspondence requires that such an MSH system possess ∣C∣ chiral Majorana edge modes per edge. These modes traverse the superconducting gap and disperse linearly near the chemical potential as a function of the momentum along the ribbon edge, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4b for the C = 3 phase. A spatial plot of the zero-energy LDOS (see Fig. 4b) demonstrates that the chiral Majorana mode is as expected localized along the edges of the ribbon, and that its spatial structure is complementary to that of the local skyrmion topological charge. The spatial structure of the skyrmion lattice, and hence of the induced α(r), is also reflected in the combined energy and spatial dependence of the LDOS (see Fig. 4c) as revealed by a line-cut of the LDOS from the bottom to the top of the ribbon along the left edge of Fig. 4b. In particular, in the center of the skyrmions, where α is the largest, the spectral weight in the LDOS is pushed to higher energies. The spatial structure of the LDOS is therefore similar to that exhibited by the MSH system at a phase transition (see Fig. 3c).

a Schematic form of a skyrmion lattice ribbon on the surface of an s-wave superconductor. b Spatial plot of the zero-energy LDOS. Inset: electronic band structure as a function of momentum, k∥ along the ribbon with a width of 27 skyrmions in the C = 3 phase. c Energy-dependent LDOS for positions from the bottom to the top of the ribbon, positions correspond to the colors at the left edge of b. d Persistent supercurrents in the skyrmion ribbon. Spatial structure of e the superconducting s-wave order parameter, Δ(r), and f the theoretically computed31 critical Josephson current Ic using an s-wave order parameter in the tip (shown area corresponds to black square in a). Spatial structure of the g real and h imaginary part of the superconducting triplet correlations between nearest-neighbor sites. Spatial structure of the theoretically computed Ic(r) with the tip possessing a i purely real and j purely imaginary triplet superconduting order parameter (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). Parameters are (JS, Δ, μ) = (0.5, 0.4, −5.5)t and R = 5a0, corresponding to the C = 3 phase, with a width of 10 skyrmions.

In addition to the chiral Majorana edge modes, the magnetic structure of the skyrmion ribbon leads to two unique physical features. The first one is the spatial form of persistent supercurrents that are induced by the broken time-reversal symmetry. While these supercurrents are generally confined to the edges of an MSH system16, the inhomogeneous magnetic structure of the skyrmion lattice leads to supercurrents (see Supplementary Note 4) that circulate around each skyrmion, not only along the ribbon’s edge but also in its interior (see Fig. 4d). These supercurrents screen the out-of-plane component of the local magnetic moments, similar to the case of a vortex lattice, and are carried by both the in-gap and bulk states. The second unique feature is the presence of spin–triplet superconducting correlations which are a necessary requirement for the emergence of topological superconductivity16. The development of JSTS26,27,28,29,30 has provided a unique opportunity to visualize not only these correlations in real space at the atomic level but also to investigate the effects of the inhomogeneous magnetic structure of the skyrmion lattice on the superconducting s-wave order parameter, Δ(r)31. Specifically, pair breaking effects of the magnetic moments lead to a spatially non-uniform suppression of Δ(r) inside the skyrmion ribbon (see Fig. 4e), with the largest suppression occurring where the induced RSO interaction is the weakest. This spatial structure of Δ(r) is well imaged by that of the critical Josephson current, Ic(r) (see Fig. 4f), that could be measured via JSTS using a tip with an s-wave superconducting order parameter (for details, see ref. 31), thus providing direct insight into the strength of local pair breaking effects. Moreover, the inhomogeneous magnetic structure of the skyrmion lattice enables the emergence of superconducting spin–triplet correlations not only in the equal-spin channels \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\downarrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) (corresponding to Cooper pair spin states Sz = ±1), but also in the mixed-spin (Sz = 0) channel, \(\left|\uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle +\left|\downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) (see Supplementary Note 5). The spatial structure of the real and imaginary parts of these correlations in the \(\left|\uparrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) channel are shown in Figs. 4g and h, respectively (the correlations in the Sz = 0, −1 channels are shown in Supplementary Note 5). These correlations are a direct consequence of the magnetic structure of the skyrmions, and thus vanish outside the ribbon. To image the spatial structure of these non-local triplet correlations, we compute Ic(r) assuming an extended (2 × 1) JSTS tip with a superconducting triplet order parameter (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). If the tip’s order parameter is chosen to be either purely real (see Fig. 4i) or purely imaginary (see Fig. 4j), the resulting Josephson current very well images the spatial structure of the real or imaginary parts, respectively, of the superconducting triplet correlations. We note that these triplet correlations can be imaged despite the fact that the MSH system possesses neither a long-range nor a local triplet superconducting order parameter. Thus JSTS can provide unprecedented insight into the existence of one of the most crucial aspects of topological superconductivity, the existence of spin–triplet correlations.

Discussion

MSH systems containing a magnetic skyrmion layer are suitable candidate systems to explore a rich topological phase diagram. By varying the skyrmion radius, which can be achieved through the application of an external magnetic field, it is possible to tune these systems between different topological phases, and explore not only their unique properties but also the transitions between them. As it was found experimentally (see the movie in the Supplemental Material of ref. 17) that the size of skyrmions can be manipulated essentially down to the limit of zero applied field, the required field strength for tuning of the skyrmion lattice is well below the upper critical field for many conventional s-wave superconductors. The origin of this tunability lies in the spatially inhomogeneous RSO interaction, which is induced by the magnetic skyrmion lattice and which carries a spatial signature in the zero-energy LDOS that can be observed at a topological phase transition. We note that the specific form of the topological phase diagram is controlled by the spatial structure of the induced RSO interaction, which in turn is determined by the radial dependence of the magnetic skyrmion. While the latter can change with increasing magnetic field17, the existence of topological phases in skyrmion MSH systems is robust against these changes. Our results present the extension to 2D topological superconductors of recent work32,33,34 which demonstrated that the manipulation of non-collinear magnetic textures imposed on a 2D superconductor—either through the application of an external magnetic field32 or current33, or through quantum engineering34—can give rise to a one-dimensional topological superconductor exhibiting localized Majorana zero modes at its ends. Moreover, skyrmion MSH systems provide a unique opportunity to employ JSTS to visualize a necessary requirement for the emergence of topological superconductivity, the existence of induced spin–triplet superconducting correlations. This, in turn, provides an experimental approach to identifying topological superconducting phases, a possibility that needs to be further explored in future studies. Our results demonstrate that the tunability of the magnetic structure in MSH systems opens a path for the quantum engineering and exploration of topological superconductivity, and the ability to engineer Majorana zero modes and chiral Majorana edge modes. This raises the intriguing question of whether a tuning of 2D topological phases, similar to the one discussed here, could also be achieved using other 2D non-collinear magnetic structures25,35,36.

Methods

Theoretical formalism

To compute the electronic structure of the skyrmion MSH system, we rewrite Hamiltonian of Eq. (1) in terms of a Hamiltonian matrix, \(\hat{H}\), in real and Nambu space, and compute the retarded Greens function matrix \({\hat{g}}^{{\rm{r}}}\) using \({\hat{g}}^{{\rm{r}}}(\omega )={\left[(\omega +i\delta )\hat{1}-\hat{H}\right]}^{-1}\). The local, spin-resolved density of states, N(r, ω, σ) at site r is then obtained via \(N({\bf{r}},\sigma ,\omega )=-{\rm{Im}}\left[{\hat{g}}^{{\rm{r}}}({\bf{r}},\sigma ;{\bf{r}},\sigma ;\omega )\right]/\pi\). The topological invariant, the Chern number C, is computed using Eq. (2). The supercurrent is calculated using the Keldysh formalism, see Supplementary Note 4. The derivation of the superconducting correlations as well as of the critical Josephson current is given in Supplementary Note 5.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Materials. Extra data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that were employed in this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Nadj-Perge, S. et al. Observation of Majorana fermions in ferromagnetic atomic chains on a superconductor. Science 346, 602–607 (2014).

Ruby, M. et al. End states and subgap structure in proximity-coupled chains of magnetic adatoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 197204 (2015).

Pawlak, R. et al. Probing atomic structure and Majorana wavefunctions in mono-atomic Fe chains on superconducting Pb surface. npj Quantum Inf. 2, 16035 (2016).

Kim, H. et al. Toward tailoring Majorana bound states in artificially constructed magnetic atom chains on elemental superconductors. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar5251 (2018).

Manna, S. et al. Signature of a pair of Majorana zero modes in superconducting gold surface states. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 8775–8782 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Evidence for Majorana bound states in an iron-based superconductor. Science 362, 333–335 (2018).

Machida, T. et al. Zero-energy vortex bound state in the superconducting topological surface state of Fe(Se,Te). Nat. Mater. 18, 811–815 (2019).

Ménard, G. C. et al. Isolated pairs of Majorana zero modes in a disordered superconducting lead monolayer. Nat. Commun. 10, 2587 (2019).

Ménard, G. C. et al. Two-dimensional topological superconductivity in Pb/Co/Si(111). Nat. Commun. 8, 2040 (2017).

Palacio-Morales, A. et al. Atomic-scale interface engineering of Majorana edge modes in a 2D magnet-superconductor hybrid system. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav6600 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence for dispersing 1D Majorana channels in an iron-based superconductor. Science 367, 104–108 (2020).

Röntynen, J. & Ojanen, T. Topological superconductivity and high Chern numbers in 2D ferromagnetic Shiba lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 236803 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Two-dimensional chiral topological superconductivity in Shiba lattices. Nat. Commun. 7, 12297 (2016).

Rachel, S., Mascot, E., Cocklin, S., Vojta, M. & Morr, D. K. Quantized charge transport in chiral Majorana edge modes. Phys. Rev. B 96, 205131 (2017).

Romming, N., Kubetzka, A., Hanneken, C., Von Bergmann, K. & Wiesendanger, R. Field-dependent size and shape of single magnetic Skyrmions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 177203 (2015).

Yang, G., Stano, P., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Majorana bound states in magnetic skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 93, 224505 (2016).

Garnier, M., Mesaros, A. & Simon, P. Topological superconductivity with deformable magnetic skyrmions. Commun. Phys. 2, 126 (2019).

Ryu, S., Schnyder, A. P., Furusaki, A. & Ludwig, A. W. Topological insulators and superconductors: tenfold way and dimensional hierarchy. N. J. Phys. 12, 065010 (2010).

Mascot, E., Cocklin, S., Rachel, S. & Morr, D. K. Dimensional tuning of Majorana fermions and real space counting of the Chern number. Phys. Rev. B 100, 184510 (2019).

Bianco, R. & Resta, R. Mapping topological order in coordinate space. Phys. Rev. B 84, 241106 (2011).

Prodan, E. Disordered topological insulators: a non-commutative geometry perspective. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 44, 113001 (2011).

Prodan, E. A Computational Non-Commutative Geometry Program for Disordered Topological Insulators (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Chen, W. & Schnyder, A. P. Majorana edge states in superconductor-noncollinear magnet interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 92, 214502 (2015).

Rodrigo, J. G., Suderow, H. & Vieira, S. On the use of STM superconducting tips at very low temperatures. Eur. Phys. J. B 40, 483–488 (2004).

Hamidian, M. H. et al. Detection of a Cooper-pair density wave in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x. Nature 532, 343–347 (2016).

Randeria, M. T., Feldman, B. E., Drozdov, I. K. & Yazdani, A. Scanning Josephson spectroscopy on the atomic scale. Phys. Rev. B 93, 161115(R) (2016).

Jäck, B. et al. Critical Josephson current in the dynamical Coulomb blockade regime. Phys. Rev. B 93, 020504(R) (2016).

Cho, D., Bastiaans, K. M., Chatzopoulos, D., Gu, G. D. & Allan, M. P. A strongly inhomogeneous superfluid in an iron-based superconductor. Nature 571, 541–545 (2019).

Graham, M. & Morr, D. K. Imaging the spatial form of a superconducting order parameter via Josephson scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 96, 184501 (2017).

Fatin, G. L., Matos-Abiague, A., Scharf, B. & Zutic, I. Wireless Majorana bound states: from magnetic tunability to braiding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 077002 (2016).

Zhou, T., Mohanta, N., Han, J. E., Matos-Abiague, A. & Zutic, I. Tunable magnetic textures in spin valves: from spintronics to Majorana bound states. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134505 (2019).

Desjardins, M. M. et al. Synthetic spin-orbit interaction for Majorana devices. Nat. Mater. 18, 1060–1064 (2019).

Nakosai, S., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Two-dimensional p-wave superconducting states with magnetic moments on a conventional s-wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 88, 180503(R) (2013).

Spethmann, J. et al. Discovery of magnetic single- and triple-Q states in Mn/Re(0001). Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 227203 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank H. Kim, A. Kubetzka, T. Posske, K. von Bergmann, and R. Wiesendanger for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award No. DE-FG02-05ER46225 (to E.M., M.G., and D.K.M.), the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes (to J.B.), and through ARC DP200101118 (to S.R.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K.M. and S.R. conceived and supervised the project. E.M., M.G., and J.B. performed the theoretical calculations. All authors discussed the results. D.K.M. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mascot, E., Bedow, J., Graham, M. et al. Topological superconductivity in skyrmion lattices. npj Quantum Mater. 6, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00299-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-020-00299-x

This article is cited by

-

Majorana zero modes in Y-shape interacting Kitaev wires

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Antiferromagnetism-driven two-dimensional topological nodal-point superconductivity

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Higher order topological superconductivity in magnet-superconductor hybrid systems

npj Quantum Materials (2023)

-

Fusion of Majorana bound states with mini-gate control in two-dimensional systems

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Interfacial phase frustration stabilizes unconventional skyrmion crystals

npj Quantum Materials (2022)