Abstract

Gap symmetry and structure are crucial issues in understanding the superconducting mechanism of unconventional superconductors. Here, we report an in-depth investigation on the out-of-plane lower critical field \(H_{c1}^c\) of fluorine-based 1111 system superconductor CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF with Tc = 21 K. A pronounced two-gap feature is revealed by the kink in the temperature-dependent \(H_{c1}^c(T)\) curve. The magnitudes of the two gaps are determined to be Δ1 = 0.86 meV and Δ2 = 4.48 meV, which account for 74% and 26% of the total superfluid density, respectively. Our results suggest that the local antiferromagnetic exchange pairing picture is favored compared to the Fermi surface nesting scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconducting (SC) mechanism is the central issue in the study of unconventional superconductors. Since the discovery of Fe-based superconductors (FeSCs),1 many efforts have been made on this problem.2 At the early stage, itinerant mechanism based on the weak correlation was accepted widely and the Fermi surface (FS) nesting (abbreviate as nesting scenario) was believed to be very crucial for the superconductivity.3,4 Later on, this scenario was challenged by other studies,5,6,7,8 especially by the discovery of KxFe2−ySe2 system without hole type FS near the Γ point.9,10,11,12 Consequently, the local antiferromagnetic exchange pairing scenario (abbreviate as local scenario), considering a stronger electron correlation, attracts more and more attentions.13,14,15,16 Despite the distinct mechanisms mentioned above, the prospective physical manifestations may be rather subtle. For example, both of them predicted a sign-changed s-wave (S±) gap symmetry. However, the FSs with a better nesting condition tend to have a stronger pairing amplitude and larger SC gap in the itinerant mechanism,17,18,19 while according to the local scenario, a larger SC gap should open on the smaller FS.13 Typically, approximations were made in the theoretical models and a precise comparison to the experimental results is difficult. In the case of 122 system Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2, for example, the larger SC gap was found to open on the FSs with a smaller size and a better nesting condition,19,20,21 which could not discriminate these two theoretical proposals. Therefore, currently more delicate experiments are required.

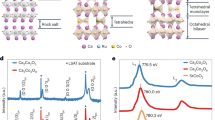

Recently, clear progresses were made on the single-crystal growth of the fluorine-based 1111 system of FeSCs, i.e. CaFeAsF22 and the Co-doped counterparts,23 and systematic investigations have been carried out on this system.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 Especially, it was found that the smaller FS around the Γ point (see the α FS in Fig. 4a) is much smaller than other FSs around M point and consequently shows a worse nesting condition,27,32 as compared with the other larger FSs, which should benefit the identification of the abovementioned itinerant and local mechanisms.

In this paper, we present a detailed investigation on the temperature dependence of the out-of-plane lower critical field \(H_{c1}^c(T)\) of the high-quality CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF single crystals. The lower critical field reflects the information of penetration depth and superfluid density, which is a good pointcut to investigate the intrinsic SC properties of FeSCs.33,34,35 The data is described by a two-component-superfluid model with two SC gaps, Δ1 = 0.86 meV and Δ2 = 4.48 meV. Considering the weighting factors for the two components, we conclude that the larger gap is most likely opened on the smaller FS, which has a bad nesting condition with other FSs. Thus our results provide a clear identification and the local antiferromagnetic exchange pairing scenario is favored.

Results

The dc magnetic susceptibility χ for the CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF sample was measured under a magnetic field of 10 Oe in zero-field-cooling and field-cooling modes, which is presented in Fig. 1a. The χ − T curve shows a sharp SC transition, which reflects the homogeneity and high quality of our sample. The onset transition temperature Tc is about 21 K. The absolute value of magnetic susceptibility χ is over 95% after the demagnetization was considered, indicating a high SC volume fraction. The isothermal M − H curves for the same sample are shown in Fig. 1b, c. The full magnetization curve shown in Fig. 1b is rather symmetric, illustrating a very low surface barrier for the flux lines when entering the sample. For the data in the low-field region as shown in Fig. 1c, one can see the evolution from the low-field linear tendency to the crooked behavior with the increase of field. The former represents an ideal Meissner state and the latter reflects the penetration of field into the interior of the sample.

Magnetization of the CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF single crystal. a Temperature dependence of volume susceptibility measured in zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) modes. b The full magnetization curves at three typical temperatures. c Field dependence of magnetic moment in the field region below 1500 Oe at different temperatures from 2 to 20 K. The intervals are 1 K/step in the range 2–10 K and 2 K/step in the range 10–20 K

In order to have a clear impression for the data in low-field region, we show the enlarged view of the isothermal M − H curves in Fig. 2a. The black dashed line represents the linear M − H relation in the very low-field region, which is a consequence of the Meissner effect. Customarily this dashed line is called the Meissner line. We checked the deviation of the magnetization data from the Meissner line to have a solid determination for the onset point of the field penetration, i.e., \(H_{c1}^c\). Field dependence of such a deviation ΔM is displayed in Fig. 2b. Two criteria, ΔM = 5 × 10−5 emu and 2.5 × 10−5 emu equivalent to 2 Oe and 1 Oe respectively, are adopted for the determination of \(H_{c1}^c\). As revealed by the two dashed lines in Fig. 2b, obviously the variation of criterion will affect the obtained \(H_{c1}^c\) values. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 3, the evolution behavior with temperature is not affected by the criterion. In addition, we found that the temperature dependent tendency from our measurements is also consistent with that obtained by the magnetic torque experiments,26 as displayed by the green asterisks. So we will focus on the analysis of the normalized values \(H_{c1}^c(T)/H_{c1}^c(0)\), which are more solid and reliable.

Magnetization data in the low-field region. a Isothermal M − H curves in the field range of 0–400 Oe. The black dashed line shows the linear fit in the low-field region, which is called Meissner line. b Deviation of magnetization data from the Meissner line. The two dashed lines are two different criteria for determining \(H_{c1}^c\). Three red arrows indicate the positions of \(H_{c1}^c\) at 2, 4, and 6 K with criteria 1. The temperature intervals for a and b are the same as those in Fig. 1c

The extracted \(H_{c1}^c(T)\) (normalized by the zero-temperature value \(H_{c1}^c(0)\)) as a function of temperature. The data from two criteria are displayed in company with that from the magnetic torque measurements.26 The solid line is the fitting curve using the two-gap model. The contributions of the two components with different gap magnitudes are also shown by the dashed lines

It is known that typically the FeSCs are in the local limit,33 thus the local London model can be used. According to the local London model, the normalized superfluid density within the ab plane \(\tilde \rho _s^{ab}\) has a close relation with the out-of-plane lower critical field \(H_{c1}^c\):33,34

Here, λab is the penetration depth within the ab plane. Moreover, the FSs in the present system are nearly ideal cylinders27,32 and the in-plane Fermi velocity is rather isotropic within the kx − ky plane. In this case, \(\tilde \rho _s^{ab}\) of the ith FS can be given by36

where f(E) is the Fermi function and Δi is the value of the energy gap in the ith FS. The temperature dependence of Δi was calculated based on the simple weak-coupling BCS model. Evidently, the kink feature around Tc/2 in Fig. 3 could not be described by an isotropic single gap model. In order to simplify the discussion, here we adopt a two-gap model and the total normalized superfluid density can be expressed as

Here, dSF,i indicates an integral over the ith FS and \(v_F^{ab}\) is the component of Fermi velocity within the ab plane.36 By tuning the values of Δi and wi, a simulating curve well describing the experimental data was obtained, as shown by the blue solid curve in Fig. 3. This consistency between our data and the fitting curve suggests that the two-gap model has grasped key features of this system. The two dashed lines reveal the contributions from the two components with Δ1 = 0.86 meV, w1 = 0.74, and Δ2 = 4.48 meV, w2 = 0.26.

Discussion

Investigating the weighting factor wi allows us to seek out the locations of the different superfluid components on the FSs. For the roughly isotropic FSs and isotropic \(v_F^{ab}\), wi is only determined by the \(v_F^{ab}\) value and the size of the ith FS (see Eq. (4)). Although the detailed correlation is diverse, both the nesting and local scenarios imply that the gap value is determined by the shape and size of the FSs,13,17,18,19 which can be derived from the calculated electronic structures. As shown in Fig. 4a, roughly the five FSs can be divided into two groups from the viewpoint of FS shape and size: the small α FS and the large ones (β/γ/δ/η) with similar sizes. Thus we only need to simply discuss and compare the two groups. By checking the energy dispersion of the calculated band structure, we estimated that the in-plane \(v_F^{ab}\) on the α FS is 1.25–2 times of that on the large ones (β/γ/δ/η). As for the FS size, however, α FS is only 1/4 of the latter. Moreover, the number of the larger FSs is four, while only one small FS is present. Considering the above factors, the weighting factor of the α FS should be clearly smaller than that of the others. Consequently, we ascribe the w2 and Δ2 to superfluid on the α FS.

Distribution of gap value and the Uemura Plot. a Theoretical SC gap value |Δ(k)| = Δ0|coskxcosky| as a function of the two-dimensional wave vector. The schematic five Fermi surfaces are also shown. b The correlations between Tc and \(\lambda _{ab}^{ - 2}\), which is proportional to the superfluid density. Points for the cuprates (including La2−xSrxCuO4+δ (La214), YBa2Cu3O7+δ (Y123), Bi2Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+δ (Bi2223), (Pr,Nd)2−xCexCuO4+δ ((Pr,Nd)214), and Sr1−xLaxCuO2 (SrLaCuO)) and the oxygen-based 1111 system (F-doped LaFeAsO and SmFeAsO ((La,Sm)FeAsO-F)) are taken from refs. 38,39. The data of K-doped BaFe2As2 (Ba122-K), MgB2, and NbSe2 are taken from refs. 33,40,41, respectively. The result of CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF (CaFeAsF-Co) is from the present work

The α FS, which has a rather bad nesting condition with other FSs, carried the superfluid with a larger gap. Evidently, this is inconsistent with the nesting scenario for the pairing mechanism. Based on the local antiferromagnetic exchange pairing, which considered the local antiferromagnetic exchange of nearest neighboring and next nearest neighbor irons, a simple gap function was proposed:13

The distribution of the gap value |Δ(k)| in the Brillouin zone is displayed in Fig. 4a by the colormap. Obviously the gap value is larger on the smaller α FS, compared with other FSs, which is qualitatively consistent with our experimental result. So the local scenario is favored for the pairing mechanism of the present system. Since both the two-gap model and the gap function (Eq. (5)) are simplified with considerable approximations, we could not carry out a precise and quantitative comparison between the experimental results and the theoretical simulations at the present stage.

Previously we estimated the value of the in-plane penetration depth \(\lambda _{ab}^{ab}(0)\) at 0 K based on the magnetic torque data.26 At that time, only the \(\lambda _{ab}^{ab}(T)\) data in the Tc/2 ≤ T ≤ Tc range were obtained and the kink was not recognized. With the more comprehensive information now, we can update λab(0) to a more precise value, 260 nm. Based on this value, we checked the Uemura plot37 which is a scaling behavior between Tc and \(\lambda _{ab}^{ - 2}\) for the SC systems with a low superfluid density. From Eq. (1), we have known that \(\lambda _{ab}^{ - 2}\) is proportional to the density of superfluid. As shown in Fig. 4b, the data of high-Tc cuprates,38 FeSCs,33,38,39 MgB2,40 and NbSe241 are displayed together. It is clear that the hole-doped cuprates and the 1111 system of FeSCs reveal a low-superfluid-density feature and follow the linear relation of the Uemura plot. The data point represented by the yellow asterisk is from the present work and rather consistent with the results of other oxygen-based 1111 systems.

To summarize, we conduct magnetization measurements on CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF single crystals, and the out-of-plane lower critical field \(H_{c1}^c\) is extracted. It is found that the temperature dependent \(H_{c1}^c\) exhibits a pronounced kink around Tc/2, which can be described by a two-gap model. Importantly, the lower superfluid density with a rather large gap is attributed to the small α FS, from which the local antiferromagnetic exchange pairing mechanism is identified to be a better candidate for understanding the unconventional superconductivity of FeSCs. Moreover, our data follow the Uemura plot quite well, indicating a low-superfluid-density feature resembling the hole-doped high-Tc cuprates.

Methods

Sample preparation

High-quality CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF single crystals were grown using CaAs as the self-flux.22,23 The detailed growth conditions and the characterizations of the samples can be seen in our previous reports.23

Magnetization measurements

The magnetization measurements were carried out on the magnetic property measurement system (Quantum Design, MPMS 3). The magnetic fields were applied along the c axis of the single crystal in all the measurements.

Band structure calculations

The first-principles calculations presented in this work were performed using the all-electron full potential linear augmented plane wave plus local orbitals method42 as implemented in the WIEN2K code.43 The exchange-correlation potential was calculated using the generalized gradient approximation as proposed by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof.44 The calculations for the parent compound were performed using the experimental crystal structure.22 The band structures for the Co-doped compound were obtained by a slight shift from the results of the parent samples based on a rigid model.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author.

References

Kamihara, Y., Watanabe, T., Hirano, M. & Hosono, H. Iron-based layered superconductor La[O1−xFx]FeAs (x = 0.05–0.12) with T c = 26 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3296–3297 (2008).

Hirschfeld, P. J., Korshunov, M. M. & Mazin, I. I. Gap symmetry and structure of Fe-based superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124508 (2011).

Mazin, I. I., Singh, D. J., Johannes, M. D. & Du, M. H. Unconventional superconductivity with a sign reversal in the order parameter of LaFeAsO1−xFx. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 057003 (2008).

Raghu, S., Qi, X.-L., Liu, C.-X., Scalapino, D. J. & Zhang, S.-C. Minimal two-band model of the superconducting iron oxypnictides. Phys. Rev. B 77, 220503 (2008).

Ma, F., Lu, Z.-Y. & Xiang, T. Arsenic-bridged antiferromagnetic superexchange interactions in LaFeAsO. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224517 (2008).

Yildirim, T. Origin of the 150-K anomaly in LaFeAsO: competing antiferromagnetic interactions, frustration, and a structural phase transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 057010 (2008).

Si, Q. & Abrahams, E. Strong correlations and magnetic frustration in the high T c iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 076401 (2008).

Borisenko, S. V. et al. Superconductivity without nesting in LiFeAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 067002 (2010).

Guo, J. et al. Superconductivity in the iron selenide KxFe2Se2(0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0). Phys. Rev. B 82, 180520 (2010).

Zhang, Y. et al. Nodeless superconducting gap in AxFe2Se2 (A = K,Cs) revealed by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Nat. Mater. 10, 273–277 (2011).

Wang, X.-P. et al. Strong nodeless pairing on separate electron Fermi surface sheets in (Tl, K)Fe1.78Se2 probed by ARPES. Europhys. Lett. 93, 57001 (2011).

Mou, D. et al. Distinct Fermi surface topology and nodeless superconducting gap in a (Tl0.58Rb0.42)Fe1.72Se2 superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 107001 (2011).

Seo, K., Bernevig, B. A. & Hu, J. Pairing symmetry in a two-orbital exchange coupling model of oxypnictides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 206404 (2008).

Xu, Y.-M. et al. Observation of a ubiquitous three-dimensional superconducting gap function in optimally doped Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. Nat. Phys. 7, 198–202 (2011).

Miao, H. et al. Isotropic superconducting gaps with enhanced pairing on electron Fermi surfaces in FeTe0.55Se0.45. Phys. Rev. B 85, 094506 (2012).

Hu, J. P. & Ding, H. Local antiferromagnetic exchange and collaborative Fermi surface as key ingredients of high temperature superconductors. Sci. Rep. 2, 381 (2012).

Mazin, I. & Schmalian, J. Pairing symmetry and pairing state in ferropnictides: theoretical overview. Physica C 469, 614–627 (2009).

Graser, S., Maier, T. A., Hirschfeld, P. J. & Scalapino, D. J. Near-degeneracy of several pairing channels in multiorbital models for the Fe pnictides. New J. Phys. 11, 025016 (2009).

Ding, H. et al. Observation of Fermi-surface-dependent nodeless superconducting gaps in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. Europhys. Lett. 83, 47001 (2008).

Zhao, L. et al. Multiple nodeless superconducting gaps in (Ba0.6K0.4)Fe2As2 superconductor from angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Chin. Phys. Lett. 25, 4402–4405 (2008).

Nakayama, K. et al. Superconducting gap symmetry of Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 studied by angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Europhys. Lett. 85, 67002 (2009).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Growth and characterization of millimeter-sized single crystals of CaFeAsF. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 28, 085008 (2015).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Growth and characterization of CaFe1−xCoxAsF single crystals by CaAs flux method. J. Cryst. Growth 451, 161–164 (2016).

Terashima, T. et al. Fermi surface with dirac fermions in CaFeAsF determined via quantum oscillation measurements. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011014 (2018).

Xiao, H. et al. Superconducting fluctuation effect in CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 455701 (2016).

Xiao, H. et al. Angular dependent torque measurements on CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 325701 (2016).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Strong anisotropy effect in iron-based superconductor CaFe0.882Co0.118AsF. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 074003 (2017).

Xu, B. et al. Optical study of dirac fermions and related phonon anomalies in the antiferromagnetic compound CaFeAsF. Phys. Rev. B 97, 195110 (2018).

Ma, Y. H. et al. Magnetic-field-induced metal–insulator quantum phase transition in CaFeAsF near the quantum limit. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 61, 127408 (2018).

Gao, B., Ma, Y., Mu, G. & Xiao, H. Pressure-induced superconductivity in parent CaFeAsF single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 97, 174505 (2018).

Mu, G. & Ma, Y. Single crystal growth and physical property study of 1111-type Fe-based superconducting system CaFeAsF. Acta Phys. Sin. 67, 177401 (2018).

Nekrasov, I. A., Pchelkina, Z. V. & Sadovskii, M. V. Electronic structure of new AFFeAs prototype of iron arsenide superconductors. JETP Lett. 88, 679–682 (2008).

Ren, C. et al. Evidence for two energy gaps in superconducting Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 single crystals and the breakdown of the uemura plot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 257006 (2008).

Wang, Z. C. et al. Giant anisotropy in superconducting single crystals of CsCa2Fe4As4F2. Phys. Rev. B 99, 144501 (2019).

Abdel-Hafiez, M. et al. Temperature dependence of lower critical field H c1(T) shows nodeless superconductivity in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 88, 174512 (2013).

Carrington, A. & Manzano, F. Magnetic penetration depth of MgB2. Physica C 385, 205–214 (2003).

Uemura, Y. J. et al. Basic similarities among cuprate, bismuthate, organic, chevrel-phase, and heavy-fermion superconductors shown by penetration-depth measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 2665–2668 (1991).

Luetkens, H. et al. Field and temperature dependence of the superfluid density in LaFeAsO1−xFx superconductors: a muon spin relaxation study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 097009 (2008).

Drew, A. J. et al. Coexistence of magnetic fluctuations and superconductivity in the pnictide high temperature superconductor SmFeAsO1−xFx measured by muon spin rotation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 097010 (2008).

Manzano, F. et al. Exponential temperature dependence of the penetration depth in single crystal MgB2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 047002 (2002).

Fletcher, J. D. et al. Penetration depth study of superconducting gap structure of 2H-NbSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 057003 (2007).

Singh, D. J. & Nordstrom, L. Planewaves, Pseudopotentials, and the LAPW Method. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2006).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Madsen, G., Kvasnicka, D. & Luitz, J. An Augmented PlaneWave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties. (Technical Universität Wien, Austria, 2001).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. 2015187), Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11204338 and 11404359), and the “Strategic Priority Research Program (B)” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDB04040300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M. designed the experiments. T.W. and Y.M. synthesized the samples and performed the measurements. W.L. performed the band structure calculations. G.M. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. T.W., Y.M., W.L., J.C., L.W., J.F., H.X., Z.L., T.H., X.L., and G.M. discussed the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Ma, Y., Li, W. et al. Two-gap superconductivity in CaFe0.88Co0.12AsF revealed by temperature dependence of the lower critical field Hc1c (T). npj Quantum Mater. 4, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-019-0173-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-019-0173-0