Abstract

Topological semimetal, a novel state of quantum matter hosting exotic emergent quantum phenomena dictated by the nontrivial band topology, has emerged as a new frontier in condensed-matter physics. Very recently, the coexistence of triply degenerate points of band crossing and Weyl points near the Fermi level was theoretically predicted and experimentally identified in MoP. Via high-pressure electrical transport measurements, we report here the emergence of pressure-induced superconductivity in MoP with a critical transition temperature Tc of ca. 2.5 K at ca. 30 GPa. No structural phase transition is observed up to ca. 60 GPa via synchrotron X-ray diffraction study. Accordingly, the topologically nontrivial band protected by the crystal structure symmetries and superconductivity are expected to coexist at pressures above 30 GPa, consistent with density functional theory calculations. Thus, the pressurized MoP represents a promising candidate of topological superconductor. Our finding is expected to stimulate further exploitation of exotic emergent quantum phenomena in novel unconventional fermion system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The low-energy, long-wavelength quasiparticle excitation near the Fermi level as counterpart of high-energy relativistic Dirac, Weyl, and Majorana fermion has been successfully demonstrated in topological quantum matter with nontrivial band topology such as topological insulator (TI), topological Dirac semimetal (TDS), topological Weyl semimetal (TWS), and topological superconductor (TSC) over the last decade.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 In stark contrast with the gapped bulk state of both TI and TSC, the defining hallmark of TDS and TWS is the presence of linear crossing points of conduction band and valence band near the Fermi level, where two or four bands are exactly degenerate at certain momentum-energy value in the first Brillouin zone, giving rise to a gapless bulk state. Novel macroscopic quantum phenomena they exhibit such as ultrahigh mobility of charge carriers, extremely large linear magnetoresistance, quantum anomalous Hall effect, and chiral anomaly are not only of fundamental interest but also hold potential applications. The recent breakthrough in predicting and identifying unconventional “new fermion” beyond conventional Dirac and Weyl fermion sparked new research interest in the field of topological semimetal.15,16,17,18,19,20 Among the symmetries of 230 crystal space groups in condensed-matter physics, the threefold, sixfold, and eightfold degenerate quasiparticle excitation emanating from the multiply degenerate points of band crossing near the Fermi level can be protected in a crystal lattice either by symmorphic rotation combined with mirror symmetries or by non-symmorphic symmetries. The novel three-component, six-component, and eight-component fermion have distinct properties from conventional Dirac and Weyl fermion, including unique surface states and transport properties. One such material hosting triply degenerate fermion, which has been experimentally identified via angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) is WC (tungsten carbide) structured MoP.19 The crystal structure of MoP belongs to the symmorphic space group P-6m2 (number 187). Within the crystal lattice, the P atom and Mo atoms are located at the 1d (1/3, 2/3, 1/2) and 1a (0, 0, 0) Wyckoff positions, respectively. The crystal structure includes the rotational symmetry C3z and the mirror symmetries M y and M z , which are crucial to topologically protecting the triply degenerate points (TPs).

Along with the quest of unconventional “new fermion,” the materialization of topological superconductivity which is topologically distinct from conventional Bose–Einstein condensates of Cooper pairs has constituted an active research theme in condensed-matter physics over the last decade. As a manifestation of the topological character, TSC promises realization of itinerant massless Majorana fermion, which may operate as topological qubit for fault-tolerant quantum computation. However, the natural occurrence of TSC is extremely scarce with the unique promising candidate being Sr2RuO4 for its spin-triplet pairing,21 despite that a wide range of candidate materials have been proposed.22,23,24,25 To date, two viable avenues to access TSC have been demonstrated, i.e., either doping or pressurizing TI, TDS, and TWS.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 However, the topologically nontrivial nature of the doping- and pressure-induced superconductivity is under heavy debate yet. Pressure, modifying the crystal structure and electronic band structure in a continuously controllable fashion, is a clean and efficient thermodynamic parameter in tuning the physical properties of topological quantum matter.36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 Here, via high-pressure electrical transport and synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements with the aid of theoretical calculations, we propose that the pressurized MoP is a promising candidate of TSC.

Results

Pressure-induced superconductivity

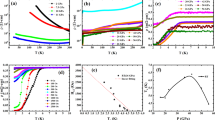

The temperature-dependent resistance at various pressures in two runs are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1a for run 1, at pressures below 30 GPa, the conducting behavior is characteristic of a normal metal without marked signature of superconductivity down to the lowest temperature measured. At 30 GPa, a slight upturn in the temperature-dependent resistance shows up at a characteristic temperature T* of ca. 2.5 K and persists up to ca. 40 GPa, as shown in Fig. 1b. As shown in Fig. S3, an external magnetic field of 0.2 T can almost smear out the resistance upturn, indicating that the resistance upturn acts as a fragile precursor for superconductivity. In the high-pressure electrical transport measurement, the temperature-dependent resistance always displays a slight upturn preceding the superconducting transition.37,38,39,43,45,46 Upon further increasing the pressure to ca. 50 GPa, superconductivity characterized by a slight drop in the temperature-dependent resistance emerges with a critical transition temperature Tc of ca. 2.5 K, as shown in Fig. 1b. The superconducting transition is broadened due to the pressure gradient throughout the sample. The Tc is defined at the point where the resistance starts to deviate from the nearly temperature-independent constant in the normal state. The magnitude of drop in the temperature-dependent resistance is progressively enhanced with pressure increasing up to ca. 60 GPa. Simultaneously, the Tc is monotonically enhanced up to ca. 3 K. As shown in Fig. 1c for run 2, at pressures below ca. 30 GPa, the conducting behavior is characteristic of a normal metal without marked signature of superconductivity down to the lowest temperature measured. Upon further increasing the pressure to ca. 30 GPa, superconductivity characterized by a slight drop in the temperature-dependent resistance sets in with a critical transition temperature Tc of ca. 2.5 K, as shown in Fig. 1d. With pressure increasing, the Tc rises monotonically up to ca. 4 K at 95 GPa. At the highest pressure of 95 GPa, zero resistance is explicitly observed, substantiating the occurrence of superconductivity.

Temperature-dependent resistance of MoP at various pressures. R–T curves in the whole temperature region for run 1(a) and run 2(c). Zoom-in of the low-temperature region for run 1(b) and run 2(d). In Fig. 1b, the characteristic temperature T* of resistance upturn and superconducting critical transition temperature Tc are indicated, respectively. Inset of Fig. 1d displays the micrograph of the electrodes connected with sample inside the diamond anvil cell

Determination of the upper critical field

To further corroborate that the precipitous drop in the temperature-dependent resistance is of superconducting origin, the effect of external magnetic field on this resistive transition was investigated at 95 GPa under external magnetic fields of up to 1 T. The onset temperature of resistance drop is significantly suppressed with increasing external magnetic field, indicative of a superconducting transition, as shown in Fig.2a. As shown in Fig. 2b, the upper critical field Hc2 defined at 90% of the resistive transition as a function of temperature is well fitted by a modified Ginzburg–Landau equation Hc2(T) = Hc2(0)*(1 − T/Tc)(1+α) with the zero-temperature upper critical field Hc2(0) of 3.75 T, which is far below the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer weak-coupling Pauli paramagnetic limit of Hp (T) = 1.84Tc (K) = 6.8 T for Tc = 3.7 K. The upward curvature of Hc2(T) close to Tc hints at a multiband superconducting pairing state, reminiscent of 2H-NbSe2 and MgB2.

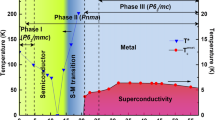

Pressure–temperature phase diagram

The pressure–temperature (P–T) phase diagram of MoP is summarized in Fig. 3a. At pressures below 30 GPa, the conducting behavior is characteristic of a normal metal without marked signature of superconductivity down to the lowest temperature measured. In run 1, a slight upturn in the temperature-dependent resistance shows up at a characteristic temperature T* of ca. 2.5 K at ca. 30 GPa and persists up to ca. 40 GPa. Upon further pressurization, superconductivity characterized by a slight drop in the temperature-dependent resistance emerges with a critical transition temperature Tc of ca. 2.5 K at ca. 50 GPa, which rises to ca. 3 K at ca. 60 GPa. In run 2, superconductivity indicated by a slight drop in the temperature-dependent resistance sets in at ca. 2.5 K at ca. 30 GPa. Upon further compression, the Tc increases monotonically up to ca. 4 K at 95 GPa. In the normal state at 5 K, no anomaly is observed in the pressure dependence of resistance, indicating no structural phase transition, as shown in Fig. 3b. In contrast, the emergence of pressure-induced superconductivity in other topological quantum matters is usually accompanied by a structural phase transition, which leads to an anomaly in the pressure dependence of normal state resistance.37,38,43

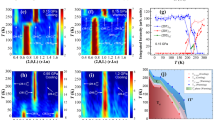

Structural stability at low temperature and high pressure

To track the structure evolution of MoP upon pressurization, high-pressure synchrotron X-ray diffraction (HPXRD) measurements were conducted at room temperature. The HPXRD patterns and results of Rietveld refinement are shown in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 4a, the WC-type crystal structure of MoP is stable against pressure up to ca. 60 GPa, indicating that the origin of pressure-induced superconductivity is irrelevant to a structural phase transition. At pressures above 25 GPa, the new peak at 2θ ~ 10° arises from the pressure transmitting medium neon, which crystallizes at ca. 25 GPa. At 2θ ~ 11°, the Miller index of (110) and (002) peak is labeled in Fig. S4. Fig. S5 shows the pressure-dependent Bragg position of (110) and (002) peak and axial compressibility (a/a0 and c/c0). The compressibility of a axis is much larger than that of c axis, as a result, the shift of (110) peak to large angle is faster than that of (002) peak with increasing pressure. Thus, the split of peak at 2θ ~ 11° is due to the different shift rate of (110) and (002) peak to large angle upon compression, not to the structural phase transition. The possibility of structural phase transition at low temperature could be affirmatively excluded from the ARPES measurements.19 In addition, there is no anomaly in the R–T curve at low temperature, indicating that no structural phase transition occurs. As seen in Fig. 4b, the lattice constants a and c, volume of unit cell and Mo–P bond length shrinks monotonically without anomaly upon pressurization. However, a kink in the pressure dependence of both the axial ratio (c/a) and the Mo–P–Mo bond angle is evident at ca. 25 GPa. This anomaly is most probably due to the strain produced by the solidification of pressure transmitting medium neon, not to the structural phase transition. Fitting the experimental V–P data by the Birch–Murnaghan equation of state and assuming the first-order pressure derivative B0’ to be 4 for the two pressure regions below and above 25.3 GPa, the bulk modulus at ambient pressure (B0) is determined to be 213(1) GPa and 238(2) GPa with the fitted volume at ambient pressure (V0) of 28.852(8) Å3 and 28.59(3) Å3, respectively. The refined lattice constants at various pressure are shown in Table S1.

High-pressure synchrotron X-ray diffraction analysis of MoP. a X-ray diffraction patterns of MoP up to 60.6 GPa at room temperature (λ = 0.31 Å). Experimental (open circle) and fitted (line) XRD patterns at 0.8 GPa and 60.6 GPa are shown, with the Rwp factor of 0.62% and 0.86%, respectively, in which the vertical lines denote the theoretical positions of the Bragg peaks. b Pressure dependence of lattice constant (a and c), volume (V), axial ratio (c/a), Mo–P bond length, and Mo–P–Mo bond angle of MoP. The cryn and green bold lines in the V–P curve represent the fitting to experimental data by the Birch–Murnaghan equation of state

Density functional theory calculation of electronic band structure at high pressure

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the pressure-induced superconductivity in MoP, we performed density functional theory calculations of the electronic band structures at high pressure. The results for band structure at ambient pressure shown in Fig. S6 agree well with the previous study,19 indicating that MoP is a topological semimetal with coexistence of Weyl fermion and triply degenerate fermion. We applied the crystal structure prediction techniques using USPEX to search for the possible high-pressure equilibrium configurations. Our simulations confirm that no structural phase transition occurs around the critical pressure where superconducting transition is observed experimentally, consistent with the HPXRD results. Pressure-dependent lattice constants (a and c), volume (V), and axial ratio (c/a) from numerical simulations is plotted in Fig. S7. The lattice constants at various pressures from numerical simulations are shown in Table S2. We can find that the simulated lattice constants at high pressure are qualitatively consistent with the experimental results shown in Fig. 4b and Table S1. Compared with the experimental counterpart, the simulated axial ratio (c/a) figures out a smooth curve without any kink around 25 GPa. Therefore, the experimentally observed kink in the axial ratio (c/a) at ca. 25 GPa is an artefact and irrelevant to the emergence of superconductivity.

Our band structure calculations with spin–orbit coupling (SOC) in Fig. 5b–d reveal that the coexisting Weyl points (WPs) and TPs survive at high pressure and all four bands crossing the Fermi level are topologically nontrivial ones contributing to the formation of Weyl fermions and/or triply degenerate fermions. The WPs and TPs are topologically protected by the crystal symmetry, which is determined to be robust at high pressure via the HPXRD study. The Fermi surfaces (FSs) of the four topological bands are plotted in Fig. 5e. Except for the two hole-type pockets around Γ and K-points, MoP has the three-dimensional electron-type FSs. It is noteworthy that the pressure qualitatively changes the band 6 in energy at K point from valence band to conduction band in the band structures without SOC, as shown in Fig. 5a. Here, the hybrid functional calculation is used to eliminate the possible overestimation of band inversion in generalized gradient approximation (GGA) and the comparison indicates that band inversions around K point and the pressure-dependent qualitative change of the band 6 in energy at K point occur in both cases. Furthermore, the pressure-dependent evolutions of the band 6 without SOC and of the bands 11 and 12 with SOC in energy at K point undergo a discontinuity between 25 and 30 GPa (Fig. S8), where the onset of superconductivity is observed experimentally.

The electronic band structure of MoP at different pressure. a The band structures calculated without SOC within GGA (black lines) and hybrid functional HSE06 (red lines). b The GGA band structures with SOC. c The GGA band structures with SOC around triply degenerate nodes along Γ-A line. d The GGA band structures with SOC around Weyl nodes at k z = ± 0.016 Å−1 planes. The Fermi level is set at zero in all band structures. e The Fermi surfaces of the four bands (crossing the Fermi level) with SOC for MoP at 30 GPa. The first two bands enclose one TRIM Γ point

Discussion

The emergence of pressure-induced superconductivity in TI Bi2Se3,43 Dirac semimetal Cd3As2,47 and Weyl semimetal TaP48 is usually accompanied by a structural phase transition, which inevitably breaks the crystal symmetry protecting the topological state. However, the pressure-induced superconductivity in MoP emerges without concomitant structural phase transition, implying the coexistence of superconductivity with nontrivial band topology at high pressure.

Theoretically, a time-reversal invariant TSC requires odd-parity symmetry and the FS enclosing an odd number of time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM).29 The states at FS of MoP are constituted by the hybridization of 4d orbital of Mo and 3p orbital of P. We note that all the four bands crossing the Fermi level are topologically nontrivial ones contributing to the formation of Weyl fermions and/or triply degenerate fermions. As these bands are spatially extended, the electron correlation is quite weak due to the strong screening effect. As we can see in Fig. 5a, the hybrid functional calculation with correlation correct does not induce significant change of the FSs compared with GGA calculations. Consequently, one can expect that the superconductivity discovered in MoP is mainly dictated by the electron–phonon interaction, which can affect the superconducting gap. As a result, the symmetry of the topologically nontrivial bands determines the symmetries of electron and phonon modes involved in the formation of Cooper pairs. However, the phonon-mediated pairing can possess odd-parity symmetry, if the electron–phonon interaction has singular behavior at long wavelengths.49 MoP has four TRIM at Γ, A, M, L points in the first Brillouin zone. As shown in Fig. 5e, both FSs of band 11 and 12 enclose one TRIM at Γ point. As a result, the existence of topological superconductivity in MoP at pressures above 50 GPa is highly favored.

To summarize, our combined experimental and theoretical high-pressure studies on the three-component fermion material MoP have offered a promising candidate of TSC. Our finding is expected to inspire further exploitation of pressure-induced superconductivity in novel unconventional fermion system.

Methods

Crystal structure characterization at ambient pressure

The single crystal sample was synthesized by Ge-flux method and has been studied by ARPES.19 Single crystal X-ray diffraction at ambient pressure was measured on Bruker D8 Venture by using Mo Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.71073Å) at 300 K and the data was refined using the SHELXL-97 program. The space group is P-6m2 (No. 187) and the lattice constants are a = b = 3.2259(3) Å, c = 3.2050(3) Å, α = β = 90°, and γ = 120°. Fig. S1 shows the XRD pattern of (00 l) plane. The characterization was performed on a Rigaku Smartlab High Resolution Diffractometer at room temperature using Cu Ka1 radiation (λ = 1.5406Å). The full width at half maximum of the (001) peak indicates high quality of our single crystal sample, as shown in Fig. S2.

High-pressure electrical transport measurements

The measurements were carried out in a screw-pressure-type diamond anvil cell made of non-magnetic Cu-Be alloy. The tungsten gasket with initial thickness of 250 μm was preindented by a pair of diamond anvil with culet size of 200 μm to a pressure of 20 GPa. The mixture of epoxy and cubic-BN powder was loaded and compressed to a pressure of 35 GPa for insulation. A flake sample was forced to contact with the four Pt probes in a van der Pauw configuration (inset of Fig.1d). Low-temperature measurements were carried out in a cryostat with a base temperature of 1.7 K (JANIS Research Company, Inc.). The pressure was determined by ruby fluorescence below 80 GPa and by diamond Raman above 80 GPa at room temperature, before and after each cooling.

HPXRD measurement

The measurement was performed at Sector 16 BMD, HPCAT at Advanced Photon Source. Pressure was generated by a pair of diamond anvils with culet size of 300 μm. Rhenium gasket was indented and a hole with a diameter of 100 μm was drilled to serve as sample chamber. Ruby ball as pressure marker were loaded together with MoP powder ground from as-grown single crystal into the sample chamber. Neon was used as pressure-transmitting medium. A monochromatic X-ray beam with incident wavelength of 0.3100 Å was used. The diffraction patterns were collected with a MAR 345 image plate detector. The two-dimensional image plate patterns were integrated into one-dimensional intensity versus 2θ data using the Fit2D software package. Refinement of the X-ray diffraction patterns was performed using the GSAS + EXPGUI software packages.

Density functional calculations

The high-pressure behavior were explored by merging the evolutionary algorithm and ab initio total energy calculations, as implemented in the USPEX code. Enthalpy and electronic structure calculation were carried out by using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package within the framework of GGA (Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange correlation functional). The ion–electron interaction was modeled by the projector augmented wave method with a uniform energy cutoff of 330 eV. The possible underestimation of band gap within GGA is checked by a nonlocal Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE06) hybrid functional calculation. Spacing between k-points was 0.02 Å−1. The geometry structures were optimized by employing the conjugate gradient technique, and in the final geometry, no force on the atoms exceeded 0.001 eV/Å. SOC for all elements was taken into account by a second variation method. The projected Wannier functions for the Mo–4d and P–3p are generated by using Wannier90. A tight-binding model based on these has been established to calculate the FSs and the position of Weyl nodal points in the Brillouin zone.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author.

References

Qi, X. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi- arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B. 83, 205101 (2011).

Hsieh, T. H. et al. Topological crystalline insulators in the SnTe materials class. Nat. Commun. 3, 982 (2012).

Dziawa, P. et al. Topological crystalline insulator states in Pb1-xSnxSe. Nat. Mater. 11, 1023–1027 (2012).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Discovery of a three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal, Na3Bi. Science 343, 864–867 (2014).

Liu, Z. K. et al. A stable three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 13, 677–681 (2014).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Discovery of a Weyl fermion semimetal and topological Fermi arcs. Science 349, 613–617 (2015).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Experimental discovery of Weyl semimetal TaAs. Phys. Rev. X 5, 031013 (2015).

Yang, L. X. et al. Weyl semimetal phase in the non-centrosymmetric compound TaAs. Nat. Phys. 11, 728–732 (2015).

He, Q. L. et al. Chiral Majorana fermion modes in a quantum anomalous Hall insulator-superconductor structure. Science 357, 294–299 (2017).

Soluyanov, A. A. et al. Type-II Weyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498 (2015).

Deng, K. et al. Experimental observation of topological Fermi arcs in type-II Weyl semimetal MoTe2. Nat. Phys. 12, 1105–1110 (2016).

Huang, L. N. et al. Spectroscopic evidence for a type II Weyl semimetallic state in MoTe2. Nat. Mater. 15, 1155–1160 (2016).

Yan, M. Z. et al. Lorentz-violating type-II Dirac fermions in transition metal dichalcogenide PtTe2. Nat. Commun. 8, 257 (2017).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Beyond Dirac and Weyl fermions: unconventional quasiparticles in conventional crystals. Science 353, aaf5037 (2016).

Weng, H., Fang, C., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Topological semimetals with triply degenerate nodal points in θ-phase tantalum nitride. Phys. Rev. B 93, 241202 (2016).

Zhu, Z., Winkler, G. W., Wu, Q. S., Li, J. & Soluyanov, A. A. Triple point topological metals. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031003 (2016).

Weng, H., Fang, C., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Co-existence of Weyl fermion and massless triply degenerate nodal points. Phys. Rev. B 94, 165201 (2016).

Lv, B. Q. et al. Observation of three-component fermions in the topological semimetal molybdenum phosphide. Nature 546, 627–631 (2017).

Shekhar, C. et al. Extremely high conductivity observed in the unconventional triple point fermion material MoP. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.03736 (2017).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076501 (2017).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Observation of unusual topological surface states in half-Heusler compounds LnPtBi (Ln = Lu, Y). Nat. Commun. 7, 12924 (2016).

Neupane, M. et al. Observation of the spin-polarized surface state in a noncentrosymmetric superconductor BiPd. Nat. Commun. 7, 13315 (2016).

Guan, S. Y. et al. Superconducting topological surface states in the noncentrosymmetric bulk superconductor PbTaSe2. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600894 (2016).

Sun, Z. X. et al. Dirac surface states and nature of superconductivity in noncentrosymmetric BiPd. Nat. Commun. 6, 6633 (2015).

Hor, Y. S. et al. Superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 and its implications for pairing in the undoped topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 057001 (2010).

Wray, L. A. et al. Observation of topological order in a superconducting doped topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 6, 855–859 (2010).

Sasaki, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217001 (2011).

Fu, L. & Berg, E. Odd-parity topological superconductors: theory and application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097001 (2010).

Hsieh, T. H. & Fu, L. Majorana fermions and exotic surface Andreev bound states in topological superconductors: application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 107005 (2012).

Levy, N. et al. Experimental evidence for s-wave pairing symmetry in superconducting CuxBi2Se3 single crystals using a scanning tunneling microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 117001 (2013).

Sasaki, S. et al. Odd-parity paring and topological superconductivity in a strongly spin-orbit coupled semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 217004 (2012).

Du, G. et al. Drive the Dirac electrons into Cooper pairs in SrxBi2Se3. Nat. Commun. 8, 14466 (2017).

Matano, K., Kriener, M., Segawa, K., Ando, Y. & Zheng, G. Q. Spin-rotation symmetry breaking in the superconducting state of CuxBi2Se3. Nat. Phys. 12, 852–854 (2016).

Yonezawa, S. et al. Thermodynamic evidence for nematic superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3. Nat. Phys. 13, 123–126 (2017).

Zhou, Y. H. et al. Pressure-induced reemergence of superconductivity in topological insulator Sr0.065Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B. 93, 144514 (2016).

Zhou, Y. H. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in a three-dimensional topological material ZrTe5. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2904–2909 (2016).

Pan, X. C. et al. Pressure-driven dome-shaped superconductivity and electronic structural evolution in tungsten ditelluride. Nat. Commun. 6, 7805 (2015).

Kang, D. F. et al. Superconductivity emerging from a suppressed large magnetoresistant state in tungsten ditelluride. Nat. Commun. 6, 7804 (2015).

Qi, Y. P. et al. Superconductivity in Weyl semimetal candidate MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 7, 11038 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Observation of superconductivity induced by a point contact on 3D Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 crystals. Nat. Mater. 15, 38–42 (2016).

Aggarwal, L. et al. Unconventional superconductivity at mesoscopic point contacts on the 3D Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 15, 32–37 (2016).

Kirshenbaum, K. et al. Pressure-induced unconventional superconducting phase in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 087001 (2013).

Zhou, Y. H. et al. Pressure-induced new topological Weyl semimetal phase in TaAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 146402 (2016).

Sun, L. L. et al. Re-emerging superconductivity at 48 kelvin in iron chalcogenides. Nature 483, 67–69 (2012).

Takahashi, H. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in the iron-based ladder material BaFe2S3. Nat. Mater. 14, 1008–1012 (2015).

He, L. P. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in the three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. NPJ Quant. Mater. 1, 16014 (2016).

Li, Y. F. et al. Concurrence of superconductivity and structure transition in Weyl semimetal TaP under pressure. NPJ Quant. Mater. 2, 66 (2017).

Wan, X. G. & Savrasov, S. Y. Turning a band insulator into an exotic superconductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 4144 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Numbers 2018YFA0305700, 2016YFA0401804, 2017YFA0302901, and 2017YFA0403600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 11674328, 51372249, 11574323, 11774399, 11474330, 11674325, 11644001, U1632275, and U1632162), and the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (Grant Number A2017004). The XRD was performed at HPCAT (Sector 16), Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. HPCAT operations are supported by DOE-NNSA under Award Number DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award Number DE-FG02-99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF. The Advanced Photon Source is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract Number DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.R.Y and Z.H.C. designed the project. Z.L.F. and Y.-G.S. grew the single crystal sample. Z.H.C., X.L.C., C.A., Y.H.Z., Y.Z., C.C.G., B.W.Z., and Y.F.Y. performed high-pressure resistance measurements. L.X.Y., C.K.B., and W.G.Y. conducted HPXRD measurements. J.G.Z. refined the X-ray diffraction data. X.P.Y. performed the density functional theory calculations with the aid of G.W. and X.G.W.. Z.H.C., X.P.Y., and Z.R.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chi, Z., Chen, X., An, C. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in MoP. npj Quant Mater 3, 28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0102-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0102-7

This article is cited by

-

Superconducting ScP4 with a novel phosphorus framework

Applied Physics A (2022)

-

Pressure-induced superconductivity and structure phase transition in Pt2HgSe3

npj Quantum Materials (2021)

-

Growth of 2D MoP single crystals on liquid metals by chemical vapor deposition

Science China Materials (2021)