Abstract

The cyclisation of a short chain into a ring provides fascinating scenarios in terms of transforming a finite array of spins into a quasi-infinite structure. If frustration is present, theory predicts interesting quantum critical points, where the ground state and thus low-temperature properties of a material change drastically upon even a small variation of appropriate external parameters. This can be visualised as achieving a very high and pointed summit where the way down has an infinity of possibilities, which by any parameter change will be rapidly chosen, in order to reach the final ground state. Here we report a mixed 3d/4f cyclic coordination cluster that turns out to be very near or even at such a quantum critical point. It has a ground state spin of S = 60, the largest ever observed for a molecule (120 times that of a single electron). [Fe10Gd10(Me-tea)10(Me-teaH)10(NO3)10]·20MeCN forms a nano-torus with alternating gadolinium and iron ions with a nearest neighbour Fe–Gd coupling and a frustrating next-nearest neighbour Fe–Fe coupling. Such a spin arrangement corresponds to a cyclic delta or saw-tooth chain, which can exhibit unusual frustration effects. In the present case, the quantum critical point bears a ‘flatland’ of tens of thousands of energetically degenerate states between which transitions are possible at no energy costs with profound caloric consequences. Entropy-wise the energy flatland translates into the pointed summit overlooking the entropy landscape. Going downhill several target states can be reached depending on the applied physical procedure which offers new prospects for addressability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coordination clusters (CCs) constructed from aggregations of paramagnetic metal ions which are cooperatively coupled may exhibit molecular-based slow relaxation of magnetisation leading to bistability, hysteresis and quantum tunnelling effects characteristic of so-called single molecule magnets.1 The intention is that such systems can be developed to provide information storage at a single molecule level giving a significantly enhanced capability for miniaturisation.2 One goal along this line is to create large ground state spins that are stabilised by an easy-axis anisotropy and whose magnetic multiplet is well separated from higher-lying levels. However, nature usually does not favour 'giant spins' since electrons are fermions that prefer to pair into non-magnetic singlets. Amongst other reasons this explains why high-spin molecules remain notoriously rare. Mn12-acetate and Fe8, both with S = 10 ground states, dominated early endeavours in the field of single molecule magnetism.3,4,5

Setting aside anisotropy for a moment, a simpler goal might be to achieve the highest possible spin state residing on a single molecule. Such a giant spin goes way beyond what can be envisaged for a single ion – S = 7/2 is the highest spin attainable among the periodic table elements. Applications for giant molecular spins include providing contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging applications through the influence of magnetic moments on relaxation processes, detectable using NMR, and molecules acting as local coolers by utilising the magnetocaloric effect (MCE) of a system, detectable using heat capacity measurements.

Finding routes to cooperatively couple open shell ions within a coordination cluster core can, indeed, lead to vastly higher spins than are imaginable for open shell single ions and a number of very high spin systems can be found in the literature6,7 including our mixed valent MnII/MnIII Mn19 coordination cluster, which holds a record ground spin state of S = 83/2.8

Recent research by us and others into mixed 3d/4f systems9,10,11 offers various means to increase both spin and total anisotropy. En route we synthesised the Gd-containing isotropic member of a new series of cyclic CCs [Fe10Ln10(Me-tea)10(Me-teaH)10(NO3)10]·20MeCN, where Ln is GdIII (1) or YIII (2). As we will demonstrate below 1 turns out to be a fascinating spin system for two reasons. It possesses a ground state spin of S = 60, which is the largest spin observed for a single molecule to date. In addition, due to strong spin frustration the ground state is situated in very close proximity to a quantum phase transition, which strongly influences the physical properties of the molecule.

Results

Synthesis and structure

This cyclic coordination cluster system is synthesised from racemic N,N-bis-(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-2-propanol (Me-teaH3), Fe(NO3)3 and Gd(NO3)3. The structures of some of these {Fe10Ln10} compounds have been published and described previously.12,13 Ten {FeGd(Me-tea)(Me-teaH)(NO3)} units (Supplementary Figure S1) are linked by pairs of alkoxo bridges to form the 20-membered elliptical nano-torus in 1 (Fig. 1a), in which the FeGd units are displaced alternately above and below the mean plane of the ring, describing a wave-like chain structure reminiscent of a Bohr closed standing wave (Fig. 1b). This nano-ellipse has a major diameter of 28.4 Å and minor diameter of 26.3 Å, and is 12.7 Å thick, based on the van der Waals surfaces of the atoms (Fig. 1c). In other words, it represents a molecular realisation of a well-defined nanoparticle within the 1–3 nm size range.

a Structure of 1 (organic H-atoms omitted), b the 'standing-wave' core (blue lines between Fe and Gd atoms to guide the eye, c two space filling views of the Fe10Gd10 nano-torus. Colour scheme: Fe = green, Gd = crimson, O = red, N = blue, C = dark grey, H = light grey; H-bonds dashed pale blue lines, bonds between Fe and Gd to bridging O orange

Within each FeGd unit, the ligand chelating the GdIII ion retains the hydroxyl proton on its methyl substituted arm, whereas the ligand chelating the FeIII ion does not, resulting in strong H-bonding between the two ligands (e.g., between O(3) and O(6) in Supplementary Figure S1). This forces the two ligands within such a unit to be of the same chirality, and in turn results in the ten ligands over one face of the ellipse to be of the R enantiomer, while those on the other side of the mean plane are S.12 This arrangement of the enantiomeric forms of the ligands means that the methyl groups can easily snuggle between the rest of the organic parts of the ligands to give a rather rigid ligand shell (Fig. 1c).

Magnetic properties

The χT product for 1 (Fig. 2a, χ = M/B) at 300 K is consistent with the value for 10+10 non-interacting FeIII (sFe = 5/2) and GdIII (sGd = 7/2) ions with g≈2.0. For 1 the monotonic increase of the susceptibility down to 3 K suggests the presence of ferromagnetic interactions between FeIII and GdIII. In addition, the maximum of the temperature dependence of the in-phase susceptibility (χ'T) of 745 cm3K/mol observed in 1 (Supplementary Figure S2) suggests a ground state with a large total spin S of at least 38, assuming g = 2. The field dependence of the magnetization (Fig. 2b) at low temperatures supports that the exchange interactions are ferromagnetic. However, the magnetization curve at fields lower than 20 kOe is offset compared with the Brillouin function calculated for a single spin S = 60 with g = 2.0. This is in line with the observation for the diamagnetic YIII system 2 that there is a weak antiferromagnetic coupling between the FeIII centres, which obviously only becomes significant at low temperatures and small fields, compare Supplementary Figure S3.

Theoretical calculations and interpretation

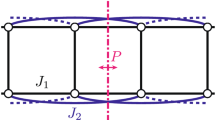

The structure of the metal skeleton together with the possible magnetic exchange interactions between the metal ions is depicted in Fig. 3. We denote the nearest-neighbour exchange interactions between each Gd and its adjacent Fe centres as J1 and the next-nearest-neighbour interactions between adjacent Fe ions as J2. The next-nearest-neighbour Gd–Gd interactions are approximated as zero, which appears reasonable for distant f-elements and a posteriori turns out to be compatible with all observables. In this configuration the iron atoms constitute the basal spins of the delta chain, compare Fig. 3, whereas the Gd atoms play the role of the apical spins. Depending on the sign and ratio of the two exchange interactions, the delta chain can exhibit several very unusual properties such as flat energy bands, extended magnetization plateaus, giant magnetization jumps as well as a quantum phase transition along with pronounced magnetocaloric effects—all driven by geometric frustration.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

Scheme of the exchange pathways assumed for the Fe10Gd10 ring: Fe ions are displayed by blue, Gd ions by red bullets. Red dashed lines show Fe–Gd interactions J1, blue lines mark Fe–Fe interactions J2; Gd–Gd interactions turn out to be zero. The structure corresponds to the one-dimensional delta or sawtooth-chain, that in the case of Fe10Gd10 has a finite length of 10 with periodic boundary conditions

Before discussing what makes the present compound so special we set out to fit the magnetic observables with the following Hamiltonian containing two Heisenberg terms describing the interactions between the magnetic ions and a Zeeman term which models the interaction with the external magnetic field.

Although both FeIII and GdIII have half-filled electron shells they might nevertheless possess non-vanishing single-ion anisotropy tensors depending on their coordination. In the present case these tensors circle around the ring structure and thus cancel to a large extent.23 This is experimentally supported by the fact that no hysteresis or ac signal has been found. Along this line, and in order to keep the numerically favourable SU(2) symmetry, we assume gGd = gFe = 2, which is a reasonable approximation both for GdIII and FeIII. But even when employing all symmetries, this large spin system with a Hilbert space dimension of 6.5 × 1016 cannot be treated with any existing exact method.24,25 The theoretical problem appears to be a challenge on its own. We thus explored four approximations to model the system, namely (1) High-Temperature Series Expansion (HTE), (2) Quantum Monte-Carlo (QMC), (3) Classical Monte-Carlo (CMC) and (4) the Finite-Temperature Lanczos Method (FTLM). None of these methods alone is capable of modelling the thermodynamic behaviour of all observables, but combined we can draw definitive conclusions.

Discussion

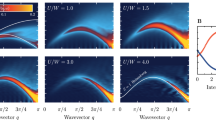

The most recent HTE code of sixth order for mixed spin systems26,27,28 yields exchange interactions J1 = 1.0 K between Fe and Gd ions and J2 = −0.65 K between adjacent Fe ions. If one considers the exchange between adjacent Gd ions, it turns out to be virtually zero. Dipolar interactions do not play a role for temperatures T ≥ 2.0 K.29 The resulting fit to the susceptibility is depicted by a black solid curve in Fig. 2a. The HTE diverges for smaller temperatures since the power series in 1/T terminates at some power, here six. QMC calculations,30,31 on the other hand, can deliver thermodynamic functions of huge spin systems as long as these systems are not frustrated. If a system is geometrically frustrated, as in the present case, QMC still works for high enough temperatures. Therefore, we compared our QMC results with those from HTE as well as with the data. As can be seen in Fig. 2a, the blue curve for QMC exactly matches the HTE curve above about 15 K. For lower T the QMC results do not converge, and are thus not shown. Also CMC calculations should yield good results since the spin quantum numbers of 5/2 for FeIII and 7/2 for GdIII are large and thus a classical approximation is appropriate. The red curve in Fig. 2a demonstrates that this expectation is indeed met. In addition to this good approximation at high temperatures, the maximum as well as the low-temperature susceptibility are also nicely reproduced with the same exchange constants. At the low temperatures at which the magnetization was measured, high-temperature methods are not applicable and CMC fails since classical spins have a length of √(s(s + 1)), which is not compatible with the saturation magnetization. QMC, although limited due to frustration, can be applied for high-enough magnetic fields since in the presence of Zeeman splitting only a few low-lying levels are accessible. The blue curves in Fig. 2b show that the parameterization in terms of J1 and J2 indeed goes through the data points for 2 and 4 K, and for 4 K even to smaller fields since the higher temperature improves convergence.

The opposite is true in terms of a modelling with the Finite-Temperature Lanczos Method (FTLM).32,33 The method provides very good approximations for thermodynamic functions up to Hilbert space dimensions of 1010. So far, the largest system treated using this approach was a GdIII12 cluster.34 However, for 1 the Hilbert space is much larger and thus we only included subspaces with total magnetic quantum number |M| > 45. This works well at low enough temperatures and large enough fields, since the large ferromagnetic ground state with S = 60 and the Boltzmann factor both favour an improvement in the approximation. The result is depicted by the red curves in Fig. 2b. The horizontal dotted line marks the lowest magnetization down to which the calculation is approximately still valid. FTLM does not work for χT vs T, since one would need to consider all M-subspaces in this case.

The final result of our endeavour is that in 1 the exchange interactions are J1 = 1.00 K between neighbouring Fe and Gd ions and J2 = −0.65 K between adjacent Fe ions with an estimated uncertainty of ±0.02 K. This immediately results in a ground state with the maximal possible total spin of S = 60, as shown in the scheme of low-lying levels (Supplementary Figure S4). The reason for the large ground state spin is that the net interaction is ferromagnetic. This might not seem immediately obvious, but can be understood in terms of the quantum phase transition we now describe. For a ferromagnetic J1 > 0 and J2 = 0 it is obvious that all spins must be aligned to the maximum possible total spin (Fig. 4). However, with a competing J2 < 0 that is increasing in magnitude the ground state will change if the ratio α = |J2|/J1 assumes the critical value αc = sGd/(2sFe) = 0.7.35,36,37

Schematic representation of a quantum phase transition. At α = α c not only the ground state changes character between a Ferromagnet (FM) and a non-collinear ferrimagnet (FiM), but also a massive degeneracy of ground state levels occurs. At T = 0 this leads to a large residual entropy, which is still noticeable at T > 0 for values of α away from the critical value (black arrow)

Since |J2|/J1 = 0.65 in 1, we are just on the ferromagnetic side of the quantum critical point (QCP). Owing to the special delta-chain structure of 1, at such a QCP the ground state becomes massively degenerate,17,35,36,37,38,39 of the order of 104, see also Supplementary Figure S5. The ratio α = 0.65 for 1 is smaller than the critical value of α c = 0.7, but very close. Near the critical point the former ground state manifold now represents a huge number of very low-lying excited states, thereby establishing an extra low-energy scale. As a result, one may find additional ultra-low temperature features in the specific heat (Supplementary Figure S6). In addition, one can observe that the specific heat is massively increased at low-temperature; the same holds for the magnetocaloric effect.35,36,37 Thus, the molecule, although not directly at the quantum critical point, acts as an observer of the quantum critical phase at elevated temperature (black arrow in Fig. 4).

Figure 5 shows the experimental specific heat per Fe–Gd pair, normalised to the gas constant (R = 8.314 J/molK) for various applied magnetic fields, which consists of the magnetic as well as the lattice contribution. The magnetic contribution is unusually large even at 20 K, and the Schottky anomaly is progressively shifted toward higher temperatures by the application of an external magnetic field (compare also Supplementary Figures S6, S7 and additional explanations in the Supplementary Information). As the quantum calculations for the similar but smaller model system Fe6Gd6, which in contrast to Fe10Gd10 can be fully treated by FTLM, demonstrate (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure S7, solid curves), the magnetic contribution to the heat capacity indeed assumes very large values, even at elevated temperatures, resulting from the unusually high density of low-lying energy levels. Although the theoretical model system Fe6Gd6 is smaller, it mimics the physical behaviour of 1 extremely well. This also holds for the specific heat at low temperatures. The essentially constant behaviour for B = 0, 0.5, and 1 T is a fingerprint of the additional low-energy scale (Supplementary Figure S5), and is reproduced for these as well as for larger magnetic fields, where the specific heat drops. We attribute the small discrepancies between model calculations and experimental data to finite size effects as well as to dipolar interactions, which are not incorporated in the model.

Finally, we would like to comment on the magnetocalorics. Figure 6 displays the isothermal entropy change, one figure of merit among magnetocaloric properties,40,41 calculated for the model system Fe6Gd6. As one can see, the entropy changes for ΔB = 7 T are very similar for the actual α = 0.65 of 1 (red) and the critical value of α c = 0.7 (dashed red). The very steep rise at the lowest temperatures signals that this compound should be a powerful cooler at liquid helium temperatures40,41,42 with impressive MCE figures for a single molecule unit [ΔS = S(7 T)-S(0 T) > 20 R at T≈3 K]. This behaviour is compared in Fig. 6 with the respective ones of analogous systems without the next-nearest interaction J2. The case with only a ferromagnetic J1 is shown by the black curve, whereas the case with only an antiferromagnetic J1 is shown as the blue curve. Whereas the latter antiferromagnetic ring would be obviously useless as a refrigerant, the ferromagnetic ring has its optimal working conditions at much higher temperatures compared to our frustrated delta chain cluster.

Normalised isothermal entropy change of the theoretically investigated system (Fe6Gd6). The red curve displays the observable for the actual α = 0.65 of 1, the dashed red for α c = 0.7, black for only ferromagnetic nearest neighbour coupling and blue for antiferromagnetic nearest neighbour coupling (colour code corresponds to Fig. 4)

In summary, the combined use of several theoretical methods confirms the record ground state spin of S = 60 for 1. Furthermore, our calculations explain its near quantum critical behaviour, which is experimentally evident in the massively enhanced specific heat. Cyclisation has thus yielded a very unusual quantum spin system with large future potential.13,43 How we can direct the molecule to move across both sides of the quantum critical point, is a future challenge. Possibilities include: using chemical means, through gating,44 and by applying pressure. Being able to move such a system so that it lies near the quantum critical point, either to the left or right of it, as well as directly on its sharp peak offers a chance to move beyond bistable systems (binary logic) as typically envisaged in our field and thence 'towards new directions in terms of control and tunability for molecular spintronics' as suggested by Roch et al. 44

Methods

Magnetic measurements were obtained using a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer MPMS-XL in the temperature range 1.8–300 K. Measurements were performed on polycrystalline samples constrained in eicosane. Magnetisation isotherms were collected at 2, 3, 5 K between 0 and 7 T. Alternating curent (ac) susceptibility measurements were performed with an oscillating field of 3 Oe and ac frequencies ranging from 1 to 1500 Hz. The data were corrected for the diamagnetic contribution of sample holder and substance. Specific heat data have been obtained with a commercial PPMS 3He system from quantum design. Heat capacity was measured on pressed pellets of micro-crystals of approx. weight of 1–2 mg by using the two-tau relaxation method. Theoretical calculations haven been performed with self-written HTE, complete diagonalization as well as FTLM program codes. QMC calculations have been done with the ALPS package using the directed loop stochastic series expansion program 'dirloop_sse'. All data are available on request from the authors.

Data availability

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the npj Quantum Materials website (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0082-7). Crystallographic details are given in the Supplementary Information, or in CCDC 1557819 available from https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All other data are available on request from the authors.

References

Gatteschi, D., Sessoli, R. & Villain, J. Molecular Nanomagnets (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006).

Leuenberger, M. N. & Loss, D. Quantum computing in molecular magnets. Nature 40, 789–793 (2001).

Thomas, L. et al. Macroscopic quantum tunnelling of magnetization in a single crystal of nanomagnets. Nature 383, 145–147 (1996).

Sessoli, R., Gatteschi, D., Caneschi, A. & Novak, M. A. Magnetic bistability in a metal-ion cluster. Nature 365, 141–143 (1993).

Wernsdorfer, W. & Sessoli, R. Quantum phase interference and parity effects in magnetic molecular clusters. Science 284, 133–135 (1999).

Powell, A. K. et al. Synthesis, structures, and magnetic properties of Fe2, Fe17, and Fe19 oxo-bridged iron clusters: the stabilization of high ground state spins by cluster aggregates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 2491–2502 (1995).

Wang, W.-G. et al. Giant heterometallic Cu17Mn28 cluster with Td symmetry and high-spin ground state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1014 (2007).

Ako, A. M. et al. A ferromagnetically coupled Mn19 aggregate with a record S = 83/2 ground spin state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 4926–4929 (2006).

Mereacre, V. et al. A bell-shaped Mn11Gd2 single-molecule magnet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9248–9249 (2007).

Mondal, K. C. et al. Coexistence of distinct single-ion and exchange-based mechanisms for blocking of magnetization in a CoII 2DyIII 2 single-molecule magnet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7550–7554 (2012).

Liu, J.-L. A heterometallic FeII–DyIII single-molecule magnet with a record anisotropy barrier. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 12966–12970 (2014).

Baniodeh, A., Anson, C. E. & Powell, A. K. Ringing the changes in FeIII/YbIII cyclic coordination clusters. Chem. Sci. 4, 4354–4361 (2013).

Baniodeh, A. et al. Unraveling the influence of lanthanide ions on intra- and inter-molecular electronic processes in Fe10Ln10 nano-toruses. Adv. Funct. Mater. 40, 6280–6290 (2014).

Sen, D., Shastry, B. S., Walsteadt, R. E. & Cava, R. Quantum solitons in the sawtooth lattice. Phys. Rev. B 53, 6401–6405 (1996).

Schulenburg, J., Honecker, A., Schnack, J., Richter, J. & Schmidt, H.-J. Macroscopic magnetization jumps due to independent magnons in frustrated quantum spin lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 167207 (2002).

Blundell, S. A. & Núñez-Reguerio, M. D. Quantum topological excitations: from the sawtooth lattice to the Heisenberg chain. Eur. Phys. J. B 31, 453–456 (2003).

Tonegawa, T. & Kaburagi, M. Ground-state properties of an s = 1/2 Δ-chain with ferro- and antiferromagnetic interactions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 272-276, 898–899 (2004).

Maksymenko, M., Honecker, A., Moessner, R., Richter, J. & Derzhko, O. Flat-band ferromagnetism as a Pauli-correlated percolation problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 096404 (2012).

Tasaki, H. Ferromagnetism in the Hubbard models with degenerate single-electron ground states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 1608–1611 (1992).

Mielke, A. Exact ground-states for the Hubbard-model on the kagome lattice. J. Phys. A-Math. Gen. 25, 4335–4345 (1992).

Zhitomirsky, M. E., Honecker, A. Magnetocaloric effect in one-dimensional antiferromagnets. J. Stat. Mech. Theor. Exp. P07012 (2004).

Schnack, J. Effects of frustration on magnetic molecules: a survey from Olivier Kahn until today. Dalton Trans. 39, 4677–4686 (2010).

Glaser, T. et al. Quantum tunneling of the magnetization in [MnIII 6M]3+ (M = CrIII, MnIII) SMMs: Impact of molecular and crystal symmetry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 289-290, 261–278 (2015).

Schnalle, R. & Schnack, J. Numerically exact and approximate determination of energy eigenvalues for antiferromagnetic molecules using irreducible tensor operators and general point-group symmetries. Phys. Rev. B 79, 104419 (2009).

Schnalle, R. & Schnack, J. Calculating the energy spectra of magnetic molecules: application of real and spin-space symmetries. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 29, 403–452 (2010).

Schmidt, H.-J., Lohmann, A. & Richter, J. Eighth-order high-temperature expansion for general Heisenberg Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. B 84, 104443 (2011).

Lohmann, A., Schmidt, H.-J. & Richter, J. Tenth-order high-temperature expansion for the susceptibility and the specific heat of spin-s Heisenberg models with arbitrary exchange patterns: Application to pyrochlore and kagome magnets. Phys. Rev. B 89, 014415 (2014).

Lohmann, A. Hochtemperaturentwicklung im Heisenberg-Modell, Diploma thesis, University of Magdeburg (2012).

Pineda, E. M. et al. Observation of the influence of dipolar and spin frustration effects on the magnetocaloric properties of a trigonal prismatic Gd7 molecular nanomagnet. Chem. Sci. 7, 4891–4895 (2016).

Sandvik, A. W. & Kurkijärvi, J. Quantum Monte Carlo simulation method for spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 43, 5950–5961 (1991).

Albuquerque, A. F. et al. The ALPS project release 1.3: Open-source software for strongly correlated systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 310, 1187–1193 (2007).

Jaklič, J. & Prelovšek, P. Lanczos method for the calculation of finite-temperature quantities in correlated systems. Phys. Rev. B 49, 5065–5068 (1994).

Schnack, J. & Wendland, O. Properties of highly frustrated magnetic molecules studied by the finite-temperature Lanczos method. Eur. Phys. J. B 78, 535–541 (2010).

Zheng, Y. et al. Molybdate templated assembly of Ln12Mo4-type clusters (Ln = Sm, Eu, Gd) containing a truncated tetrahedron core. Chem. Commun. 49, 36–38 (2013).

Krivnov, V. Ya, Dmitriev, D. V., Nishimoto, S., Drechsler, S.-L. & Richter, J. Delta chain with ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions at the critical point. Phys. Rev. B 90, 014441 (2014).

Dmitriev, D. V. & Krivnov, V. Ya Delta chain with anisotropic ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions. Phys. Rev. B 92, 184422 (2015).

Dmitriev, D. V. & Krivnov, V. Ya. Kagome-like chains with anisotropic ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic interactions. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 215801 (2017).

Suzuki, H. & Takano, K. Exact degenerate ground states for the F–AF spin chain with bond alternation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 113701 (2008).

Richter, J., Schulenburg, J., Honecker, A., Schnack, J. & Schmidt, H.-J. Exact eigenstates and macroscopic magnetization jumps in strongly frustrated spin lattices. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, S779–S784 (2004).

Evangelisti, M. & Brechin, E. K. Recipes for enhanced molecular cooling. Dalton Trans. 39, 4672–4676 (2010).

Sessoli, R. Chilling with magnetic molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 43–45 (2012).

Sharples, J. W. et al. Quantum signatures of a molecular nanomagnet in direct magnetocaloric measurements. Nat. Commun. 5, 5321 (2014).

Ghirri, A. et al. Probing edge magnetization in antiferromagnetic spin segments. Phys. Rev. B 79, 224430 (2009).

Roch, N., Florens, S., Bouchiat, V., Wernsdorfer, W. & Balestro, F. Quantum phase transition in a single-molecule quantum dot. Nature 453, 633–637 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Synchrotron Light Source ANKA for provision of instruments at the SCD beamline. J.S. thanks for computing time at the Leibniz Rechenzentrum in Garching. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) funded transregional collaborative research centre SFB/TRR 88 '3MET'. J.S. thanks the DFG for funding (SCHN 615/20-1, SCHN 615/23-1). J.R. as well thanks the DFG for funding (RI 615/21-2). We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.P. formulated the project. A.B. performed the synthesis. G.B. and C.E.A. measured the dataset for the crystal structure, and C.E.A. solved and refined the structure. Y.L. performed the magnetic susceptibility measurements and N.M. performed the initial evaluation of the chain model. M.A. measured the low-temperature high-field specific heat. J.S. and J.R. carried out the theoretical calculations. J.S. and A.K.P. wrote the paper and all authors contributed to discussions and the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baniodeh, A., Magnani, N., Lan, Y. et al. High spin cycles: topping the spin record for a single molecule verging on quantum criticality. npj Quant Mater 3, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0082-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0082-7

This article is cited by

-

Counteracting dephasing in Molecular Nanomagnets by optimized qudit encodings

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Frustrated magnet for adiabatic demagnetization cooling to milli-Kelvin temperatures

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Low-temperature spin dynamics of ferromagnetic molecular ring {Cr8Y8}

npj Quantum Materials (2020)

-

Quantum hardware simulating four-dimensional inelastic neutron scattering

Nature Physics (2019)

-

Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of a giant {Ni21Gd20} cage with a S = 91 spin ground state

Nature Communications (2018)