Abstract

Superconductivity and topological quantum states are two frontier fields of research in modern condensed matter physics. The realization of superconductivity in topological materials is highly desired; however, superconductivity in such materials is typically limited to two-dimensional or three-dimensional materials and is far from being thoroughly investigated. In this work, we boost the electronic properties of the quasi-one-dimensional topological insulator bismuth iodide β-Bi4I4 by applying high pressure. Superconductivity is observed in β-Bi4I4 for pressures, where the temperature dependence of the resistivity changes from a semiconducting-like behavior to that of a normal metal. The superconducting transition temperature Tc increases with applied pressure and reaches a maximum value of 6 K at 23 GPa, followed by a slow decrease. Our theoretical calculations suggest the presence of multiple pressure-induced topological quantum phase transitions as well as a structural–electronic instability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dirac materials such as topological insulators (TI),1,2,3 Dirac semimetals (DSM),4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and Weyl semimetals (WSM)13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 have topologically nontrivial band structures and therefore exhibit unique quantum phenomena. Achieving a superconducting state, which is the state of quantum condensation of paired electrons, in topological materials has already led to some unprecedented discoveries. Indeed, the realization of superconductivity in topological compounds has been regarded as an important step toward topological superconductors.

Superconductivity has been induced by using doping or pressure in TIs (Bi2Se3,22,23,24,25 Bi2Te3,26,27,28 Sb2Te329), DSMs (Cd3As2,30,31,32 ZrTe5,33 and HfTe534), and WSMs (TaAs,35 TaP,36 WTe2,37, 38 and MoTe239). However, from a structural perspective, most topological materials are limited to two-dimensional or three-dimensional structures. Superconductivity has not been thoroughly explored in low-dimensional topological materials. Recently β-Bi4I4 has been theoretically predicted and experimentally confirmed as a new Z2 TI.40 Importantly, β-Bi4I4 crystallizes in a quasi-one-dimensional (quasi-1D) structure and thus hosts highly anisotropic surface-state Dirac fermions.

In this work, we systematically investigate the high-pressure behavior of the novel quasi-1D TI β-Bi4I4. Through ab initio band structure calculations, we find that the application of pressure alters the electronic properties and leads to multiple topological quantum phase transitions: from strong TI (STI) to weak TI (WTI) and back to STI. Corresponding anomalies are visible in pressure-dependent resistivity data. Superconductivity is observed in β-Bi4I4 when the temperature dependence of ρ(T) changes from a semiconducting-like behavior to that of a normal metal. The superconducting transition temperature Tc increases with applied pressure and reaches a maximum value of 6 K at 23 GPa for β-Bi4I4, followed by a slow decrease.

Results

Structure and transport properties under ambient pressure

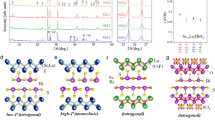

Prior physical property measurements, β-Bi4I4 crystals used for the study were structurally characterized using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis confirms that the single crystals are homogeneous and that the atomic ratio of elements is Bi:I = 53.8(2):46.2(4), in agreement with previously reported data.40 β-Bi4I4 crystallizes in a monoclinic structure (space group C12/m1, No. 12), as shown in Fig. 1a, b. The 1D building blocks of β-Bi4I4, aligned along the b-axis, can be viewed as narrow nanoribbons of a bismuth bilayer (four Bi atoms in width) terminated by iodine atoms. The atomic arrangement of β-Bi4I4 was determined using HAADF-STEM images and diffraction patterns (Fig. 1c). One primitive cell consists of four I atoms and four Bi atoms, which can be divided into two non-equivalent types of atoms: inner Bi1 atoms that bind to three bismuth atoms and peripheral Bi2 atoms that are saturated by covalent bonds to four iodine atoms.

Crystal structures of β-Bi4I4. a Crystal structure of β-Bi4I4 viewed along the chain direction (lattice vector b = [010] projection). The red, green, and blue spheres represent the Bi1, Bi2, and I atoms, respectively. Solid lines indicate covalent bonds. b Atomic structure of an individual chain-like building block of β-Bi4I4. c HAADF-STEM image of β-Bi4I4 along the [010] zone and corresponding electron diffraction pattern

Electrical resistivity at high pressure

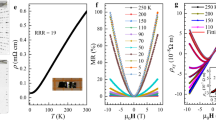

In Fig. 2 the temperature dependence of the resistivity ρ(T) of β-Bi4I4 for various pressures is shown. For P = 0.5 GPa, ρ(T) displays a semiconducting-like behavior similar to that observed at ambient pressure40, 41; however, our crystals do not show an upturn below ≈100 K.40 In a low-pressure region, increasing the pressure initially induces a weak but continuous suppression of the overall magnitude of ρ with a minimum occurring at Pmin = 3 GPa. Upon further increasing the pressure, the resistivity starts to increase gradually, reaching a maximum at a pressure above 8 GPa.

Evolution of the electrical resistivity as a function of pressure for β-Bi4I4. a, b Electrical resistivity as a function of temperature for pressures up to 40 GPa. The temperature dependence of ρ(T) changes from semiconducting-like behavior to that of a normal metal. c, d Electrical resistivity drop and zero-resistivity behavior at low temperature for pressures of 13.5–23.0 and 24.1–39.5 GPa, respectively. Here, Tc increases under increasing pressure and the maximum superconducting transition temperature corresponding to Tc = 6 K at 23.0 GPa. e Temperature dependence of resistivity under different magnetic fields for β-Bi4I4 at 21.8 GPa. f Temperature dependence of the upper critical field for β-Bi4I4. Here, Tc is determined as the 90% drop of the normal state resistivity. The solid lines represent the fits based on the Ginzburg–Landau formula

As the pressure is further increased above 8.8 GPa, ρ rapidly decreases, exhibiting semiconductor-like behavior for β-Bi4I4 (Fig. 2b). As pressure increases up to 13.5 GPa, the normal state behaves as a metal, and a small drop of ρ is observed at the lowest temperatures (experimental Tmin = 1.9 K). Zero resistivity is achieved for P ≥ 17.6 GPa, indicating the emergence of superconductivity. The critical temperature of superconductivity, Tc, gradually increases with pressure, and the maximum Tc of 6 K is attained at P = 23 GPa, as shown in Fig. 2c. Beyond this pressure, Tc decreases slowly, showing a dome-like behavior (Fig. 2d).

The appearance of bulk superconductivity in β-Bi4I4 is further supported by the evolution of the resistivity-temperature curve with an applied magnetic field. The superconducting transition gradually shifts toward lower T with the increase of the magnetic field (Fig. 2e). A magnetic field μ0H = 2.5 T removes all signs of superconductivity above 1.9 K. The upper critical field μ0Hc2 is determined using the 90% points on the transition curves, and plots of Hc2(T) are shown in Fig. 2f. A simple estimate using the conventional one-band Werthamer–Helfand–Hohenberg approximation, neglecting the Pauli spin-paramagnetism effect and spin–orbit interaction,42 i.e., μ0Hc2(0) = −0.693 × μ0(dH c2 /dT) × Tc, yields a value of 2.5 T for β-Bi4I4. We also used the Ginzburg–Landau formula to fit the data:

where t = T/Tc, yielding a critical field μ0Hc2 = 2.7 T for β-Bi4I4. Both values are comparable with those determined for superconducting Bi2Se3 and BiTeI under pressure.24,25, 43 According to the relationship μ0Hc2 = Φ0/(2πξ2), where Φ0 = 2.07 × 10−15 Wb is the flux quantum, the coherence length ξGL(0) is 11.5 nm for β-Bi4I4. Note that the extrapolated values of Hc2(0) are well below the Pauli–Clogston limit.

About the origin of the superconductivity, we noted that the Tc for β-Bi4I4 is very close to that of elemental bismuth under pressure (6 vs. 8 K).44 The possible scenarios of decomposition into elemental bismuth and BiI3 should be taken into account.45 Recently, Pisoni et al. carried out chemical characterization of the pressure-treated samples and ruled out decomposition into Bi and BiI3 at room temperature condition.46 So we conclude that the observed superconductivity is intrinsic to β-Bi4I4, and cannot be ascribed to the Bi impurity.

Discussion

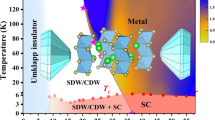

The pressure dependence of the resistivity at room temperature and the critical temperature of superconductivity for β-Bi4I4 are summarized in Fig. 3. The resistivity of β-Bi4I4 exhibits a non-monotonic evolution with increasing pressure. Over the whole temperature range, the resistivity is first suppressed with applied pressure and reaches a minimum value at about 3 GPa. As the pressure further increases, the resistivity increases with a maximum occurring at 8 GPa. Then, the resistivity abruptly decreases. Superconductivity is observed after the temperature dependence of ρ(T) changes from a semiconducting-like behavior to that of a metal. The superconducting Tc increases with applied pressure, and a typical dome-like evolution is obtained.

Electronic P-T phase diagram for β-Bi4I4. a Superconducting Tc is shown as function of pressure. The green and blue circles represent the Tc extracted from different resistivity measurements. As the pressure increases to ≈13 GPa, superconductivity is observed above experimental Tmin and persists up to pressures near 40 GPa. A dome-like evolution is observed with a maximum Tc of 6 K attained at P = 23 GPa. The resistivity values at 300 K are also shown. The resistivity of β-Bi4I4 exhibits a more complicated feature, which demonstrates that high pressure dramatically alters the electronic properties in β-Bi4I4. b Schematic illustrations of the band structure evolution under various pressures. In the STI phase, band inversion occurs at one time-reversal-invariant momentum (TRIM) points of the Brillouin zone; however, in the WTI phase, band inversion occurs at two TRIM points. In metals the Fermi level crosses the bands

The presented results demonstrate that high pressure dramatically alters the electronic properties in β-Bi4I4. To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the physical properties of β-Bi4I4, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations for the electronic band structures. Because of the underestimated band gap within the local density approximation or generalized gradient approximation (GGA), we employed the hybrid functional method (HSE) to calculate the electronic properties. The calculated band structures and density of states (DOS) are displayed in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. At zero pressure, the HSE calculations predict a narrow indirect band gap of 40.9 meV, with a valence band maximum (VBM) at the M point and a conduction band minimum (CBM) at the Y point. The component of VBM is mainly the p orbital of Bi1 with odd parity, while the CBM is mainly the p orbital of Bi2 with even parity. The band dispersion is relatively weak along the AГYM path, which is perpendicular to the quasi-1D chain, indicating weak interaction between the chains. In contrast, the strong dispersion along the BГ direction indicates strong interaction within the chain. Thus, the dispersion clearly reflects the quasi-1D character of β-Bi4I4.

Calculated band structure and density of state of β-Bi4I4. a–e Band structure of β-Bi4I4 at 0, 2.4, 6.0, 11.1, and 13.3 GPa, respectively. The size of red (blue) filled circles represents the fraction of Bi1 (Bi2) 5p states. Band inversion clearly occurs between the Bi1 5p and Bi2 5p states. The dashed line represents the Fermi level. f Evolution of the electronic density of states with increasing pressure

From the band structure at zero pressure β-Bi4I4 is in a STI phase with a band inversion at the Y point. As pressure increases, the CBM and the VBM meet at the M point. Band inversion occurs and the structure is driven into a WTI phase.47 For the process of band inversion, the band gap decreases to zero and then reopens. Therefore, the resistivity decreases before the band gap closes and then increases after the band gap reopens. This trend is roughly consistent with the experimental resistivity values (see Fig. 3). When pressure continues increasing, the band at the Y point is inverted back, and the structure returns to the STI phase. This phase evolution is also shown in Fig. 3b. When the pressure increases, the DOS near the Fermi level increases (see Fig. 4f). We also note that the increase of the DOS is mainly due to the flat bands near the Fermi level in the band structure. These heavy bands may exhibit low mobility, which may be the reason for the additional increase in resistivity in our experiments.

The pressure-induced multiple topological quantum phase transitions in β-Bi4I4 are unusual, and in addition β-Bi4I4 shows an electronic instability. DFT calculations indicate that the crystal structure abruptly changes at a critical pressure of 11.5 GPa. We can see that the lattice parameter along the quasi-1D chain direction decreases, while the parameters in the other two directions suddenly increase (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). We also calculated the bond length within the Bi plane. Bond 2 (bond 1) suddenly increases (decrease) at the critical pressure (Supplementary Fig. 3c), which is further confirmed by the phonon spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 4). Near 11.5 GPa, an imaginary phonon mode appears, which corresponds to vibrations along the quasi-1D chain and leads to the collapse of the lattice along the chain direction. From the electronic band structure calculations we can see that, after the lattice constant changes, the structure is driven from an STI to a metal. The Fermi level crosses the band (see Fig. 4e) and the DOS increases near the Fermi level (see Fig. 4f). Indeed, the resistivity abruptly decreases above the critical pressure and superconductivity is observed in β-Bi4I4 when the temperature dependence of ρ(T) changes from a semiconducting-like behavior to that of a metal.

Recently Pisoni et al. performed in situ high-pressure synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements and showed amorphization of β-Bi4I4 under high pressure.46 It is very interesting that an amorphous phase of Bi4I4 could support superconductivity. This will stimulate further studies from both experimental and theoretical perspectives.

As a novel TI, β-Bi4I4 offers a new platform for exploring exotic physics with simple chemistry. We find multiple topological quantum phase transitions under high pressure and β-Bi4I4 shows electronic instabilities. Superconductivity is induced after the nonmetal-to-metal transition in β-Bi4I4, which may be attributed to electronic and structure instabilities.

After we submitted this paper, we learned that similar work was carried out independently by another group.46

Methods

Single-crystal growth and characterization

Single crystals of β-Bi4I4 were obtained from gas-phase reactions using methods similar to those described in refs. 40,41, 48 Thoroughly ground mixtures of bismuth metal and HgI2 were used as starting materials. The Bi to HgI2 molar ratio was 1:2 with a total mass of ≈3 g. After evacuation and sealing, the ampoule was inserted into a furnace with a temperature gradient of 210–250 °C with the educts in the hot zone. The ampoule was tilted by 20–30°, the cold end pointing upward. After 2 weeks, needle-like crystals of size 5 × 1 × 0.5 mm had grown in the cold zone. The structures of the β-Bi4I4 crystals were investigated using SXRD with Mo Ka radiation. To analyze the atomic structure of the material, transmission electron microscopy was performed.

Experimental details of high-pressure measurements

Resistivity measurements were performed under high pressure in a non-magnetic diamond anvil cell. A mixture of epoxy and fine cubic boron nitride powder was used for the insulating gaskets, and platinum foil with a thickness of 5 μm was used for electrodes. The diameters of the flat working surface of the diamond anvil and the hole in the gasket were 500 and 200 μm, respectively. The sample chamber thickness was ≈40 μm. Resistivity was measured using an inverting dc current with the van der Pauw technique implemented in a typical cryogenic setup at zero magnetic field, and the magnetic field measurements were performed on a magnet-cryostat (PPMS-9, Quantum Design, Tmin = 1.8 K). Pressure was measured using the ruby scale for small chips of ruby placed in contact with the sample.49

DFT calculations

DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)50 with a plane-wave basis. The interactions between the valence electrons and ion cores were described using the projector-augmented wave method.51, 52 The exchange and correlation energy was formulated using the GGA with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof scheme.53 Van der Waals corrections were also included via a pairwise force field of the Grimme method.54, 55 Because GGA usually underestimates the band gap, we used Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE) screened Coulomb hybrid density functionals to calculate the electronic band structures and Z2 topological invariant.56, 57 The HSE band structure was obtained by the interpolated Wannier function supplied by the Wannier90 code.58 The Z2 topological invariant was calculated by the products of parity eigenvalues of all the occupied bands at the time-reversal-invariant momentum (TRIM) points.59 The plane-wave basis cutoff energy was set to 176 eV by default. The Γ-centered k points with 0.03 Å−1 spacing were used for the first Brillouin-zone sampling. The structures were optimized until the forces on the atoms were less than 5 meV Å−1. The pressure was derived by fitting the total energy dependence on the volume using the Murnaghan equation.60 Note that spin-orbit coupling was included in the static calculation. The phonon dispersion was performed using the finite displacement method with VASP and PHOHOPY code,61 and a supercell with all lattice constants larger than 10.0 Å was employed to calculate the phonon spectra.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fu, L., Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Topological insulators in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 106803 (2007).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Young, S. M. et al. Dirac semimetal in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 140405 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Dirac semimetal and topological phase transitions in A3Bi (A = Na, K, Rb). Phys. Rev. B 85, 195320 (2012).

Wang, Z., Weng, H., Wu, Q., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Three-dimensional Dirac semimetal and quantum transport in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 125427 (2013).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Discovery of a three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal, Na3Bi. Science 343, 864–867 (2014).

Liu, Z. K. et al. A stable three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 13, 677–681 (2014).

Borisenko, S. et al. Experimental realization of a three-dimensional Dirac semimetal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 027603 (2014).

He, L. P. et al. Quantum transport evidence for the three-dimensional Dirac semimetal phase in Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 246402 (2014).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Observation of Fermi arc surface states in a topological metal. Science 347, 294–298 (2015).

Liang, T. et al. Ultrahigh mobility and giant magnetoresistance in the Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 14, 280–284 (2015).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Wan, X., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Computational design of axion insulators based on 5d spinel compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 146601 (2012).

Burkov, A. A. & Balents, L. Weyl semimetal in a topological insulator multilayer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 127205 (2011).

Xu, G., Weng, H., Wang, Z., Dai, X. & Fang, Z. Chern semimetal and the quantized anomalous hall effect in HgCr2Se4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 186806 (2011).

Bulmash, D., Liu, C.-X. & Qi, X.-L. Prediction of a Weyl semimetal in Hg1-x-yCdxMnyTe. Phys. Rev. B 89, 081106 (2014).

Weng, H., Fang, C., Fang, Z., Bernevig, B. A. & Dai, X. Weyl semimetal phase in noncentrosymmetric transition-metal monophosphides. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011029 (2015).

Huang, S.-M. et al. A Weyl Fermion semimetal with surface Fermi arcs in the transition metal monopnictide TaAs class. Nat. Commun. 6, 7373 (2015).

Soluyanov, A. A. et al. Type-II Weyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498 (2015).

Sun, Y., Wu, S.-C., Ali, M. N., Felser, C. & Yan, B. Prediction of Weyl semimetal in orthorhombic MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 92, 161107 (2015).

Hor, Y. S. et al. Superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 and its implications for pairing in the undoped topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 057001 (2010).

Kriener, M., Segawa, K., Ren, Z., Sasaki, S. & Ando, Y. Bulk superconducting phase with a full energy gap in the doped topological insulator CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 127004 (2011).

Kirshenbaum, K. et al. Pressure-induced unconventional superconducting phase in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 087001 (2013).

Kong, P. P. et al. Superconductivity of the topological insulator Bi2Se3 at high pressure. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 362204 (2013).

Zhang, J. L. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in topological parent compound Bi2Te3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 24–28 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. Phase diagram of a pressure-induced superconducting state and its relation to the Hall coefficient of Bi2Te3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 83, 140504 (2011).

Matsubayashi, K., Terai, T., Zhou, J. S. & Uwatoko, Y. Superconductivity in the topological insulator Bi2Te3 under hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Rev. B 90, 125126 (2014).

Zhu, J. et al. Superconductivity in topological insulator Sb2Te3 induced by pressure. Sci. Rep. 3, 2016 (2013).

Aggarwal, L. et al. Unconventional superconductivity at mesoscopic point contacts on the 3D Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Nat. Mater. 15, 32–37 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Observation of superconductivity induced by a point contact on 3D Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 crystals. Nat. Mater. 15, 38–42 (2016).

He, L. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in the three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal Cd3As2. npj Quantum Mater. 1, 16014 (2016).

Zhou, Y. H. et al. Pressure-induced semimetal to superconductor transition in a three-dimensional topological material ZrTe5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2904–2909 (2015).

Qi, Y. et al. Pressure-driven superconductivity in the transition-metal pentatelluride HfTe5. Phys. Rev. B 94, 054517 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Discovery of tip induced unconventional superconductivity on Weyl semimetal. Sci. Bull. 62, 425–430 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Superconductivity induced by high pressure in Weyl semimetal TaP. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.02548 (2016).

Kang, D. et al. Superconductivity emerging from a suppressed large magnetoresistant state in tungsten ditelluride. Nat. Commun. 6, 7804 (2015).

Pan, X.-C. et al. Pressure-driven dome-shaped superconductivity and electronic structural evolution in tungsten ditelluride. Nat. Commun. 6, 7805 (2015).

Qi, Y. et al. Superconductivity in Weyl semimetal candidate MoTe2. Nat. Commun. 7, 11038 (2016).

Autes, G. et al. A novel quasi-one-dimensional topological insulator in bismuth iodide [beta]-Bi4I4. Nat. Mater. 15, 154–158 (2016).

Filatova, T. G. Electronic structure, galvanomagnetic and magnetic properties of the bismuth subhalides Bi4I4 and Bi4Br4. J. Solid State Chem. 180, 1103–1109 (2007).

Werthamer, N. R., Helfand, E. & Hohenberg, P. C. Temperature and purity dependence of the superconducting critical field, Hc2. III. Electron spin and spin-orbit effects. Phys. Rev. 147, 295–302 (1966).

Qi, Y. et al. Topological quantum phase transition and superconductivity induced by pressure in the bismuth tellurohalide BiTeI. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605965 (2017).

Li, Y., Wang, E., Zhu, X. & Wen, H.-H. Pressure-induced superconductivity in Bi single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 024510 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Pressure induced superconductivity in the antiferromagnetic Dirac material BaMnBi2. Sci. Rep. 7, 1634 (2017).

Pisoni, A. et al. Pressure effect and superconductivity in the β-Bi4I4 topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 95, 235149 (2017).

Liu, C.-C., Zhou, J.-J., Yao, Y. & Zhang, F. Weak topological insulators and composite weyl semimetals: β-Bi4X4 (X = Br, I). Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 066801 (2016).

von Schnering, H. G., von Benda, H. & Kalveram, C. Wismutmonojodid BiJ, eine Verbindung mit Bi(0) und Bi(II). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 438, 37–52 (1978).

Mao, H. K., Xu, J. & Bell, P. M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi-hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 91, 4673–4676 (1986).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Heyd, J. & Scuseria, G. E. Assessment and validation of a screened Coulomb hybrid density functional. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 7274–7280 (2004).

Mostofi, A. A. Wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685–699 (2008).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Topological insulators with inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045302 (2007).

Murnaghan, F. D. The compressibility of media under extreme pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 30, 244–247 (1944).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Y.Q. acknowledges financial support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. The authors thank Horst Blumtritt for the FIB sample preparation and Dr. Yurii Prots for single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies. This work was financially supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; Project EB 518/1–1 of DFG-SPP 1666 “Topological Insulators”) and by the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Grant No. 291472 “Idea Heusler”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and L.W. prepared the samples, P.W., K.G.R., and S.P. performed TEM studies, Y.Q., P.N., W.S., and S.M. performed high-pressure electrical resistivity, W.J.S. and B.Y. carried out the theoretical calculations. All authors discussed the results of the studies. Y.Q., B.Y., W.S., and W.J.S. co-wrote the paper. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, Y., Shi, W., Werner, P. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity and topological quantum phase transitions in a quasi-one-dimensional topological insulator: Bi4I4. npj Quant Mater 3, 4 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0078-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-018-0078-3

This article is cited by

-

Pressure-induced superconductivity and modification of Fermi surface in type-II Weyl semimetal NbIrTe4

npj Quantum Materials (2021)

-

Pressure-induced superconductivity and structure phase transition in Pt2HgSe3

npj Quantum Materials (2021)