Abstract

Metals containing cerium exhibit a diverse range of fascinating phenomena including heavy fermion behavior, quantum criticality, and novel states of matter such as unconventional superconductivity. The cubic system CeIn3 has attracted significant attention as a structurally isotropic Kondo lattice material possessing the minimum required complexity to still reveal this rich physics. By using magnetic fields with strengths comparable to the crystal field energy scale, we illustrate a strong field-induced anisotropy as a consequence of non-spherically symmetric spin interactions in the prototypical heavy fermion material CeIn3. This work demonstrates the importance of magnetic anisotropy in modeling f-electron materials when the orbital character of the 4f wavefunction changes (e.g., with pressure or composition). In addition, magnetic fields are shown to tune the effective hybridization and exchange interactions potentially leading to new exotic field tuned effects in f-based materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anisotropy is a key parameter defining the nature and dimensionality of correlated electron materials. Real space structure can cause nesting features of the electronic structure in momentum space that lead to density waves,1 and electronic and magnetic anisotropies in momentum space are believed to be important ingredients to enhance the transition temperature of superconductors.2 Furthermore, f-electron materials possess strong spin–orbit coupling, which can generate anisotropy in spin space.3 Despite this, it is generally believed that the minimal models required to understand correlated electron phenomena observed in transition metal and f-electron materials, such as the Hubbard, Anderson, or Kondo lattice models, do not rely on these anisotropies. Hence, the study of cubic materials, which naturally minimize the complexities added by momentum–space and real-space anisotropies, is particularly desirable to make comparison with these “simple” models, which themselves are exceedingly difficult to solve.

The cubic system CeIn3 exhibits a phenotypical phase diagram of a heavy fermion superconductor: it orders antiferromagnetically (AFM) at ambient pressure (T N ≈ 10 K), which can be suppressed by moderate pressures around 25 kbar accompanied by a small dome of superconductivity (\(T_{\rm{c}}^{\max }\) ≈ 200 mK) around the quantum critical point associated with the destruction of the Néel order at zero temperature.4 This is typical for heavy fermion superconductors thought to be mediated by quantum critical spin fluctuations.5 At the same time, the material at ambient pressure shows an enigmatic quantum critical transition at a field around 40 T, accompanied by a divergence of the electronic effective mass observed by quantum oscillation experiments.6 Here we show the sudden emergence of magnetic anisotropy at a similar field scale. The critical magnetic field required to suppress the AFM order, H c(T), is isotropic up to the 40 T range, but becomes anisotropic at higher fields. Because of strong spin–orbit coupling, the exchange interaction between Ce moments is naturally anisotropic. However, it is usually difficult to determine the full Hamiltonian and spherically symmetric effective models are often sufficient to describe many f-electron materials.7 As we will demonstrate, the measured anisotropy of the H − T phase diagram exposes the failure of a spherically symmetric model. Subsequently, we derive a minimal model that accurately captures the anisotropy in this prototypical heavy fermion material.

Results

The large magnetic field scales, in excess of 50 T, required to suppress the AFM order in CeIn3 can only be achieved by pulsed field techniques. As CeIn3 is a good metal at low temperatures, pulsed field magnetoresistance (MR) measurements are commonly afflicted by self-heating due to eddy currents and suffer from small signal to noise ratio due to their low resistivity. We fabricate microstructures from CeIn3 bulk crystals with cross-sections on the μm2 scale by focused ion beam (FIB) micromachining to address these issues (see Methods). A typical device and its resistivity is shown in Fig. 1. The extrapolated resistivity at zero temperature is at ρ 0 ≈ 4 μΩcm similar to that of the parent crystal from which the structure was fabricated. The resistivity increases up to a maximum around 50 K followed by a sharp drop of resistance at T N, in agreement with the behavior of bulk crystals.8, 9

Resistivity of a CeIn3 microstructure as a function of temperature in zero field. Both the characteristic upturn of resistance down to 70 K as well as the sharp drop of resistance at T N ≈ 10 K are characteristic features of bulk CeIn3. Inset: SEM micrograph of a typical microstructure fabricated by FIB machining, designed for a four-terminal resistivity measurement. The crystalline material was patterned into a meandered resistor shape (purple) and contacted by FIB-deposited platinum leads (blue)

Figure 2a shows the MR for fields up to 92 T that was measured at the National High Magnetic Field facility in Los Alamos. The MR increases in all field directions up to a field of H * ≈ 40–45 T. The comparatively large MR is to be expected as the main source of scattering in the material are spin fluctuations, as evidenced by the sharp drop in resistance at the magnetic ordering transition at 10 K in zero field (Fig. 1). The field scale of the MR maximum agrees well with previous reports of a Lifshitz transition associated with a heavy f-electron band.6 Eventually at higher fields, the destruction of the AFM order is clearly observed as a sharp break-in-slope of the MR at all temperatures. One key experimental finding is directly evident in the data of Fig. 2a. The critical field of the [100] direction at the lowest temperatures (600 mK) is substantially larger than that in the [110] or [111] directions.

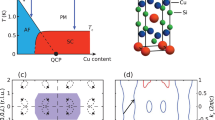

a Magnetoresistance of CeIn3 at 600 mK for fields up to 92 T along the directions [100], [110], and [111]. While for both the [110] (blue) and [111] (red) directions a break in slope (marked by arrows) indicates the destruction of the AFM order at a critical field H c ≈ 60 T, the AFM phase exists up to substantially larger fields H c ≈ 80 T along the [100] direction (black). b Calculated crystal field-level spectrum of CeIn3 for fields along [100] and [111]. For H//[100] the upper energy level of the field-split ground-state doublet and the lowest-energy state of the upper quartet (bold lines) anticross in the field range where the critical field anisotropy appears. The overlap of each wavefunction with the ground-state doublet in zero field \(\left( {{W_{{\Gamma _7}}} \equiv {{\left\| {\left\langle {\Gamma _7^1|\Psi } \right\rangle } \right\|}^2} + {{\left\| {\left\langle {\Gamma _7^2|\Psi } \right\rangle } \right\|}^2}} \right)\) is shown with the color scale. For H//[100] the two lowest-energy states retain the orbital character of the zero field Γ7 doublet (green) up to ≈40 T. Above 40 T the orbital character of the upper energy state of the field-split doublet obtains some Γ8 character (purple). Similar mixing is not appreciable for H//[111] because the lowest-energy state of the quartet is the eigenstate of (J x + J y + J z)/\(\sqrt 3\) with eigenvalue 3/2. This state and its time-reversed partner (−3/2) cannot mix with any of the other four states because they transform differently under a ±2π/3 rotation about the [111] axis

MR curves for temperatures from 10 K down to our base temperature of 0.6 K are shown in Fig. 3 for magnetic field applied along [100], [110], and [111] directions. The critical field for each temperature can easily be extracted by the kink in the MR or a minimum in dρ/dH. The temperature dependence of the critical fields is shown in Fig. 4a. For the [110] and [111] directions, the critical fields approach a similar value H c(0 K) ≈ 60 T with an approximately linear slope. The phase line along these directions is well described by \({T_{\rm{N}}} = {T_0}\left( {1 - \frac{{{H^2}}}{{H_{\rm{c}}^2}}} \right)\), and is in quantitative agreement with previous phase boundaries determined by pulsed field magnetization measurements on powders.10 The field direction [100] is remarkably different. An anisotropic H − T phase diagram develops above 40 T, and in fields above 60 T, T N(H) is approximately field-independent, followed by a sudden collapse at 80 T.

Magnetoresistance of CeIn3 at various temperatures for field applied along the directions (a) [100], (b) [110], and (c) [111]. The lower panels display the field derivative of the magnetoresistance dMR/dH shown in the upper panels. The minimum in dMR/dH identifies the critical field needed to suppress the magnetism

a Boundary of the AFM phase in the temperature and magnetic field plane. While the critical lines are nearly perfectly isotropic in lower fields, they start to differ at fields above ≈40 T and become strongly anisotropic at higher fields with a pronounced foot observed for fields along [100]. b Computed mean field phase diagram assuming spherically symmetric exchange interactions between cerium ions. The exchange interaction is chosen by the Néel temperature in zero magnetic field. The shaded region for H//[111] represents the region where a collinear Ising AFM order is the predicted ground state as opposed to the usual case of a canted AFM state. c Calculated mean field phase diagram allowing cubic anisotropy in the exchange interactions between cerium ions

Discussion

One potential origin of this anisotropy in a cubic system is the evolution of the crystal field splitting in strong magnetic fields. As the Zeeman energy becomes comparable to the crystal field energies, the orbital character of the Ce 4f wavefunctions may change, which will modify their exchange interactions. Figure 2b shows the lowest crystal field states and their orbital characters for fields along the [100] and [111] directions. In zero magnetic field, the cubic crystal field environment in CeIn3 splits the J = 5/2 multiplet into a Γ7 doublet ground state and a Γ8 quartet excited state by 12 meV.11, 12 With an applied magnetic field the Zeeman interaction causes additional splitting, which will eventually favor a field-polarized state. A cubic crystal field environment creates an anisotropic response with respect to the field direction.13,14,15,16 For CeIn3, the anisotropy tends to be rather weak at low magnetic fields below ~40 T. However, for fields applied along [100] around 40 T, the upper field-split Γ7 state and the higher-energy quartet begin to repel one another. Consequently, the orbital character of the lowest energy doublet changes significantly (see Fig. 2b). Because 40 T has not yet quenched the magnetic state in CeIn3, we can expect the magnetic exchange interaction to differ at fields beyond 40 T due to the change in orbital content as a consequence of the crystal field-level crossings.17, 18 Note that for fields applied along [111] and [110] the field necessary to change the character of the lowest doublet of states is substantiantially higher, thereby creating anisotropy in the field response of CeIn3 above 40 T. This provides a natural explanation for the origin of the anisotropy in CeIn3.

To gain further insight into the intriguing field-induced anisotropy, we derive a minimal low-energy effective model for CeIn3 under an applied magnetic field that can reproduce the above phase diagram and is consistent with the known magnetic properties of CeIn3 (see Supplementary Information for details). For simplicity, we work with an effective model for the interaction between the f-moments, which should arise from integrating out the conduction electrons of the microscopic “high-energy” model. We first diagonalize the cubic crystal field Hamiltonian determined by inelastic neutron scattering in zero magnetic field11 with a Zeeman contribution due to the applied magnetic field (Fig. 2b). For the temperature and field range of interest, we note that, at most, two states are relevant for the low-energy physics. Hence, we can always project our exchange interactions onto an effective low-energy doublet, whose character is evolving with an applied field, so long as the exchange interaction is much smaller than the crystal field splitting of 12 meV. The changing character of the ground-state doublet has been observed by neutron-scattering measurements in a field as low as 4.65 T.19 The simplest exchange interaction for a system possesses spherical symmetry of the form:

with only nearest neighbor hopping terms on a simple cubic lattice with basis vectors e ν (with ν = x, y, z). Given that the range of the interaction does not affect the mean field treatment that we describe below, we are allowed to replace the long-range RKKY interaction by an effective short-range interaction. Descriptions beyond the mean field level must include the further neighbor exchange terms associated with the RKKY interaction. \({\cal H}_{\boldsymbol{r}}^{{\rm{CF}}}\) is the crystal field Hamiltonian and \({\cal H}_{\boldsymbol{r}}^{\rm{Z}}\) = g J μ B H⋅J r is the Zeeman term with the Landé g-factor g J = 6/7 for an f-electron in a J = 5/2 multiplet. A Hamiltonian of this form has often been successfully utilized to explain the behavior of f-electron systems.7, 12 By projecting this onto the low-energy doublet we obtain an effective low-energy Hamiltonian of the form:

where \({{\cal K}_i}\) and \(\tilde h\) are effective, field-dependent exchange and Zeeman interactions, respectively, and c is a field-dependent constant (see Supplementary Information). There are several important points to emphasize in this resulting model. It is clear that an applied magnetic field breaks the cubic crystalline symmetry, resulting in an easy plane spin Hamiltonian (for H//[100] or [111] symmetry dictates that \({{\cal K}_1}\) = \({{\cal K}_2}\) resulting in an XXZ model). Importantly though, this effect can be large relative to the strength of the original Zeeman interaction. This is because the orbital character of the wavefunctions evolves with magnetic field. Hence, the effective exchange interactions (\({{\cal K}_i}\)) are also strongly dependent on the magnetic field amplitude and direction. For similar reasons, the field dependence of the Zeeman-like contribution (\(\tilde h\)) becomes nonlinear in the effective model.

A mean field solution of this model yields T N(H) for the three field directions as shown in Fig. 4b. We fix, I ex, by noting that the exact Néel temperature for a S = 1/2 cubic Heisenberg lattice based on quantum Monte Carlo calculations is \({T_{\rm{N}}} \simeq 0.94{\kern 1pt} {{\cal K}_i}(H = 0)\) and \({I_{{\rm{ex}}}} = 9{\kern 1pt} {{\cal K}_i}(H = 0){\rm{/}}25\).20 From T N = 10 K we obtain \({{\cal K}_i}(H = 0)\) = 1 meV. Our mean field solution underestimates the exact Néel temperature and must be scaled up by a factor of 1.89 to compare more directly with the experiment. Note that, although the mean field solution needs to be scaled at finite temperature, it is exact for determining the critical field at T = 0. As can be seen in Fig. 4b the mean field solution has terrible agreement with the experimentally observed field dependence of T N. The source of the peculiar field dependence of T N in the spherical model arises from the strong field dependence of the effective exchange interactions and Zeeman field (see Supplementary Information).

A solution to this poor agreement is found by recognizing that, despite common practice, spherical symmetry needs not be imposed on the system. Hence, we replace the exchange term in Eq. (1) with the simplest exchange interaction that obeys the cubic symmetry of the lattice:

where the operators d r and q r are the projections of the operator J r onto the ground-state doublet and the excited-state quartet of the zero field crystal field Hamiltonian, respectively. In essence, this allows for the exchange interaction between orbitals with Γ7 symmetry to differ from those with Γ8 symmetry accounting for the difference in overlap of these orbitals with the conduction electrons that mediate the exchange interaction. By expressing the operators d r and q r as a function of J r (see Supplementary Information) one can see that in addition to breaking the spherically symmetric exchange interaction, \({{\cal H}_{\rm ex}}\) also implicitly includes multipolar interactions (products of four or more J components), which are absent in Eq. (1). The presence of multipolar interactions comparable or even larger than the bilinear interactions distinguishes f-electron materials from 3d-based magnetic compounds. Projecting this exchange interaction onto the field-dependent low-energy doublet produces a Hamiltonian of the same form as Eq. (2), with different functional field dependences for \({{\cal K}_i}\) and \(\tilde h\) (see Supplementary Information). Using a mean field solution as we did above, we determine the Néel temperature as a function of external magnetic field strength H along [001], [110], and [111] (see Fig. 4c). As in the spherically symmetric case, the parameter \(I_{{\rm{ex}}}^{{\rm{(0)}}}\) is set by the H = 0 Néel temperature. In addition, the T = 0 critical field of 80 T for H//[100] and the kink near 60 T determine \(I_{{\rm{ex}}}^{{\rm{(1)}}}\) = 0.5 meV and \(I_{{\rm{ex}}}^{{\rm{(2)}}}\) = −1.6 meV. Strikingly, the complete H − T phase diagram in all directions now reproduces the experimental phase diagram. In particular, the field independence of T N above 60 T, followed by the sudden collapse at 80 T for H//[100] is well reproduced. Additional coupling terms (such as other multipolar couplings21) could be added, but the good agreement between our model using the basis of eigenstates from the crystal field Hamiltonian and the experimental data suggests that these terms are not dominant.

The presence of strong spin–orbit interactions and crystal field effects are well known to produce anisotropic exchange interactions.3, 22, 23 Spherically symmetric interactions, however, are often successfully employed to explain the magnetic behavior of f-electron materials including CeIn3.7, 12 We have demonstrated the failure of the spherically symmetric model in the prototypical cubic heavy fermion material CeIn3 by revealing a remarkable anisotropy under an applied magnetic field. The origin of this anisotropy is naturally explained by considering the evolution of the 4f wavefunctions’ orbital character with magnetic field. In tetragonal materials, such as the related material CeRhIn5, the orbital character of the 4f wavefunctions can also be manipulated as a function of doping or pressure.24 As seen in this high field study, the exchange interactions can vary significantly, and even change sign, as the orbital character changes (see Supplementary Information). The ability to produce a simple model capturing the consequences of strong spin–orbit coupling and varying crystal electric fields in the prototypical heavy fermion CeIn3 is an important step toward a microscopic understanding that couples the spin degrees of freedom to the conduction electrons leading to unconventional quantum critical and superconducting states in f-electron systems. Additionally, we note that magnetic fields of order 100 T are becoming increasingly available world-wide. This work illustrates that the effective exchange interactions and their anisotropy can be easily manipulated on such a scale, giving rise to the possibilities of novel field-induced phenomena, such as re-entrant superconductivity, and using magnetic field as a tuning parameter for the degree of quantum fluctuations.25

Methods

Single crystals of CeIn3 were grown using an indium flux technique.26 From a large single crystal a resistivity device was prepared using FIB micromachining. The sample design consists of a meandered current path in between the voltage and current contacts for a four-terminal resistance measurement. The small conductor width (900 nm) limits the eddy currents in the sample, while the large aspect ratio of the 630 μm long path with a cross-section of 2.8 μm2 strongly increases the total device resistance and hence the signal. In addition, the compact design of the devices reduces the loop area in the circuitry, leading to a very low noise background induced by the strong vibrations in a pulsed magnet. A typical device is shown in the inset of Fig. 1. This fabrication process has already been successfully applied to the heavy fermion metals URu2Si2,27 and CeRhIn5,28 and details on the technique can be found in these references.

Data availability

The data sets generated by the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Monceau, P. Electronic crystals: an experimental overview. Adv. Phys. 61, 325–581 (2012).

Monthoux, P., Pines, D. & Lonzarich, G. Superconductivity without phonons. Nature 450, 1177–1183 (2007).

Siemann, R. & Cooper, B. R. Planar coupling mechanism explaining anomalous magnetic structures in cerium and actinide intermetallics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 44, 1015–1019 (1980).

Walker, I., Grosche, F., Freye, D. & Lonzarich, G. The normal and superconducting states of CeIn3 and CePd2Si2 on the border of antiferromagnetic order. Phys. C 287, 303–306 (1997).

Mathur, N. D. et al. Magnetically mediated superconductivity in heavy fermion compounds. Nature 394, 39–43 (1998).

Sebastian, S. E. et al. Heavy holes as a precursor to superconductivity in antiferromagnetic CeIn3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 7741–7744 (2009).

Jensen, J. & Mackintosh, A. R. Rare Earth Magnetism (Clarendon Press, 1991).

Morin, P. et al. Magnetic structures under pressure in cubic heavy-fermion compounds. J. Low Temp. Phys. 70, 377–391 (1988).

Grosche, F. M. et al. Superconductivity on the threshold of magnetism in CePd2Si2 and CeIn3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 13, 2845–2860 (2001).

Ebihara, T., Harrison, N., Jaime, M., Uji, S. & Lashley, J. C. Emergent uctuation hot spots on the Fermi surface of CeIn3 in strong magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 246401 (2004).

Lawrence, J. M. & Shapiro, S. M. Magnetic ordering in the presence of fast spin fluctuations: a neutron scattering study of CeIn3. Phys. Rev. B 22, 4379–4388 (1980).

Knafo, W. et al. Study of low-energy magnetic excitations in single-crystalline CeIn3 by inelastic neutron scattering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 15, 3741–3749 (2003).

Paschen, S. & Larrea, J. Ordered phases and quantum criticality in cubic heavy fermion compounds. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 83, 061004 (2014).

Bredl, C. D., Steglich, F. & Schotte, K. D. Specific heat of concentrated kondo systems: (La, Ce)Al2 and CeAl2. Z. Phys. B 29, 327–340 (1978).

Chochrane, R. W., Hedgecock, F. T., Strom-Olsen, J. O. & Williams, G. Magnetic anisotropy of CeAl2. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 7, 137–139 (1978).

Mushnikov, N. V. et al. Magnetic anisotropy of pure and doped YbInCu4 compounds at ambient and high pressures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 15, 2811–2823 (2003).

Ranke, P. J., Pecharsky, V. K., Geschneidner, K. A. & Korte, B. J. Anomalous behavior of the magnetic entropy in PrNi5. Phys. Rev. B 58, 14436–14441 (1998).

Vollmer, R. et al. Low-temperature specific heat of the heavy-fermion superconductor PrOs4Sb12. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 057001 (2003).

Boucherle, J. X., Flouquet, J., Lassailly, Y., Palleau, J. & Schweizer, J. Magnetic form factor of cerium in the intermetallic compound CeIn3. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 31, 409 (1983).

Yasuda, C. et al. Néel temperature of quasi-low-dimensional Heisenberg antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 217201 (2005).

Custers, J. et al. Destruction of the Kondo effect in the cubic heavy-fermion compound Ce3Pd20Si6. Nat. Mater. 11, 189–194 (2012).

Jackeli, G. & Khaliullin, G. Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: from Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009).

Nussinov, Z. & van den Brink, J. Compass models: theory and physical motivations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1–59 (2015).

Willers, T. et al. Correlation between ground state and orbital anisotropy in heavy fermion materials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 112, 2384–2388 (2015).

Si, Q. Quantum criticality and global phase diagram of magnetic heavy fermions. Phys. Stat. Sol. B 247, 476–484 (2010).

Canfield, P. C. & Fisk, Z. Growth of single crystals from metallic fluxes. Phil. Mag. B 65, 1117–1123 (1992).

Harrison, N. et al. Magnetic field-tuned localization of the 5f-electrons in URu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 88, 241108 (2013).

Moll, P. J. W. et al. Field-induced density wave in the heavy-fermion compound CeRhIn5. Nat. Commun. 6, 6663 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Christoph Geibel and Joe Thompson for stimulating discussions, as well as Nick Wakeham for characterizing preliminary samples. Synthesis and preliminary characterization measurements of the crystals were performed at Los Alamos under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science project “Complex Electronic Materials.” Theoretical calculations were performed with the support of the Los Alamos National Laboratory LDRD program. High field measurements were supported by the DOE BES project “Science of 100 Tesla” at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, a facility that is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1157490 and the State of Florida. The work in Germany was supported by the Max-Planck-Society and funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) MO 3077/1-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J.W.M. and F.R. designed the research. E.D.B. synthesized the crystals. P.J.W.M., T.H., N.H., R.D.M., L.E.W., B.J.R., M.K.C., F.F.B., and B.B. performed and analyzed the measurements. S.S.Z. and C.D.B. performed the calculations. P.J.W.M., C.D.B., and F.R. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moll, P.J.W., Helm, T., Zhang, SS. et al. Emergent magnetic anisotropy in the cubic heavy-fermion metal CeIn3 . npj Quant Mater 2, 46 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0052-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0052-5

This article is cited by

-

The reverse quantum limit and its implications for unconventional quantum oscillations in YbB12

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Magnetic and electrical property study on La-diluted Kondo lattice CeIn3

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2024)

-

A microscopic Kondo lattice model for the heavy fermion antiferromagnet CeIn3

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Kondo quasiparticle dynamics observed by resonant inelastic x-ray scattering

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Tunable emergent heterostructures in a prototypical correlated metal

Nature Physics (2018)