Abstract

In analogy to all-electric spintronics, all-electric valleytronics, i.e., valley manipulation via electric means, becomes an exciting new frontier as it may bring revolutions in the field of data storage with ultra-high speed and ultra-low power consumption. The existence of the anomalous valley Hall effect in ferrovalley materials demonstrates the possibility of electrical detection for valley polarization. However, in previously proposed valley-polarized monolayers, the anomalous valley Hall effect is controlled by external magnetic fields. Here, through elaborate structural design, we propose the antiferrovally bilayer as an ideal candidate for realizing all-electric valleytronic devices. Using the minimal k·p model, we show that the energy degeneracy between valley indexes in such system can be lifted by electric approaches. Subsequently, the anomalous valley Hall effect strongly depends on the electric field as well. Taking the bilayer VSe2 as an example, all-electric tuning and detecting of anomalous valley Hall effect is confirmed by density-functional theory calculations, indicating that the valley information in such antiferrovalley bilayer can be reversed by an electric field perpendicular to the plane of the system and easily probed through the sign of the Hall voltage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coupling between ferroic order parameters is of great scientific and technological interest due to its potential application in the information processing industry.1, 2 Compared with the control of degrees of freedom by the traditional magnetic field or the more advanced spin-current method, manipulation via purely electric means wins the most attention.3,4,5,6,7 Over the past few years, the electric approach, with advantages of ultra-high speed and ultra-low power consumption, has been successfully applied in spintronics to control magnetic order,8 domain structures,9 spin polarization,10, 11 and even magnetization reversal.12, 13 It opens an emerging branch of spintronics, i.e., all-electric spintronics, and brings revolutions in the next-generation data storage.14

Following the arrival of atomically thin two-dimensional (2D) electronic systems,15, 16 valleytronics,17,18,19 which is the cousin of spintronics, has opened up additional opportunities for functional devices rooted in the valley degree of freedom.20,21,22,23,24 Very recently, the concept of ferrovalley material, a system with spontaneous valley polarization, is proposed,25 implying the practical use of valley index, as a new type of binary state, in a nonvolatile way similar to the spin of electrons. Owing to the existence of the anomalous valley Hall effect (AVHE), additional charge accumulations make the valley polarization an electrically measurable physical quantity in such intrinsically polarized materials. However, the valley polarization originates from the inherent exchange interaction in previous study.25 The energy-intensive magnetic way is thus necessary for the proposed ferrovalley monolayers to control its polarity, and then the sign of the Hall voltage in the AVHE. In this context, tuning the AVHE through advantageous electric methods is highly desirable and of great importance for the research on all-electric valleytronics.

In this Letter, we propose a way to achieve the electrical control of the AVHE by introducing an antiferrovalley bilayer system. This is inspired by recent successful applications of the reversible electric approach to manipulate valley-contrasting properties of bilayer graphene,20, 26,27,28,29,30,31 and the more promising transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) bilayers.32, 33

The realization of the effect hinges on optionally control of valley degeneracy through an electric field. Initially, owing to the antiferrovalley coupling between single layers, band structures between two valley indexes are degenerate, demonstrating an inversion symmetric system with absence of AVHE. Similar to what happens in graphene and pristine TMDs bilayers, an applied gate voltage breaks the spatial symmetry and leads to a potential difference between monolayers. All of the subbands from one layer move upward with respect to those from the other, lifting the valley degeneracy energetically. The AVHE, then, naturally appears. In such case, valley degeneracy couples to the electrically controlled inversion symmetry, rather than the intrinsic exchange interaction in ferrovalley monolayers. Thus, energetically splitting between valleys and subsequently the sign of Hall voltage in the AVHE strongly depend on the direction of the applied electric field. In consideration of the fact that the AVHE itself is electrically detectable, both the tuning and probing of the AVHE through desirable electric means can be implemented in such a bilayer system, providing an attractive platform towards all-electrically reading and writing memory devices.

Following the strategy, we take the concrete bilayer VSe2 as an example. Both the k·p model and first-principles calculations show that the AVHE, as we expected, can be controlled by an electric field perpendicular to the plane of the material, suggesting the potential use of such antiferrovalley bilayers in all-electric valleytronic applications.

Results

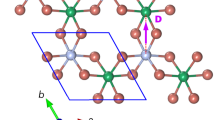

We start by considering antiferrovalley bilayers of typical TMDs in H-type stacking, where one monolayer sits on the other with 180° rotation (Fig. 1a). Monolayers are in ferrovalley state with opposite magnetic moment to guarantee the presence of the combined symmetry consisting of time-reversal and space-inversion operators. A minimal k·p model in the neighborhood of points K ± can be established by adding interlayer hopping term H ⊥ to the two-band model of ferrovalley monolayers.25 An external electric field is taken into account as the term H E . The total Hamiltonian is, then, expressed as follows (see the Supplementary Material, Sec. I for detailed expressions of terms):

Note that signs of the terms originating from the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) effect H SOC, as well as that of the ones from exchange interaction H ex, are reversed for the upper and lower monolayers. The former is due to the exchanged valley index, imported by the H-type valley-alignment. The antiferrovalley coupling causes the opposite magnetic moment between two single layers, and then directly leads to the latter.

The antiferrovalley bilayer, its band structures and the VHE. In the absence of external electric field, a schematic views of the antiferrovalley bilayer with H-type stacking. Silvery, red, and blue spheres represent chalcogen, spin-up, and spin-down transition-metal atoms, respectively. b The band structures near points K ±. Optical selection rules for the top VB are plotted. σ + and σ − correspond to the left-handed and right-handed radiations, accordingly. The irreducible representations of states have been labeled using the Mülliken notations. c Illustration of the VHE in moderately p-doped antiferrovalley bilayers. The carriers denoted by ‘+’ symbol are holes. Upward (downward) arrows with red (blue) color indicate spin-up (spin-down) states

Structurally, the antiferrovalley bilayer can be regarded as strongly bonded 2D chalcogen-transition metal-chalcogen monolayer that are loosely coupled to the other by van der Walls interactions.23 The interlayer hopping is, therefore, inappreciable compared with the intralayer ones. In such case, the simplified superposition of band structures for two single layers is applied in Fig. 1b to schematically describe electrons behavior in the bilayer.

We emphasize in advance that the chirality of valley depends on its symmetry rather than the symbol K + or K − itself. On account of the circularly polarized optical selectivity for valleys, signs K σ + and K σ − are adopted to distinguish them. When the states at a certain valley correspond to left-handed radiations, they are situated at the valley K σ +. Inversely, for the case excited by right-handed light, the valley is defined as K σ −.

For the pristine H-type bilayer without E field (belonging to the D 3d point group), spatial inversion symmetry, accompanying with antiferrovalley layer coupling, results in energetically degenerated band structures between two monolayers. However, their spin-states, and more importantly the valley indexes, are opposite. Optical selections rules (see the Supplementary Material, Sec. II for details) show that for the inversion symmetric bilayer, electrons occupying the double-degenerated valance band (VB) maxima can be excited by both the right- and left-handed lights, indicating the energy equivalency between two valley indexes.

To explore the Hall effect in the antiferrovalley system, we inspect a moderate hole-doping bilayer. In such case, the majority carriers are spin-down holes from the valley K σ + of the upper monolayer and spin-up K σ − holes from the lower layer. It is interesting to point out that according to the Eq. (SE6) in the Supplementary Material, the two monolayers possess the same magnitude but opposite sign of Berry curvatures for the majority carriers. Then, when a longitudinal bias voltage is applied, the spin-up and spin-down holes gain transverse velocities in opposite directions and accumulate toward right and left side of the ribbon, accordingly (Fig. 1c). Although the accumulation of carriers in the boundary of the upper and lower layer come from the same K − point, they respectively correspond to the left and right circularly polarized radiations. Their opposite chirality of valley index indicates that besides the spin ones, there exists valley accumulations on sample sides. Such a phenomenon exactly exhibits the valley Hall effect (VHE). As we know, in representative TMDs bilayers, such as bilayer MoS2, the VHE should be induced and tuned by an electric field.33 Here, even without any external fields, it directly happens. The presence of the VHE is consistent with valley degeneracy in the antiferrovalley bilayer.

When a vertical external bias is applied, the bilayer loses its inherent inversion symmetry and now holds the C 3v point group. From the view of band structures, as diagramed in Fig. 2, previous energy degeneracy between two monolayers is decoupled with an interlayer potential difference. A positive (negative) electric field moves the subbands from the lower (upper) layer upward, with respect to those from the upper (lower) monolayer. As a result, band structures are no longer energetically spin and valley degenerate. Since the external bias is effective to break and optionally tune the valley degeneracy, its manipulation for AVHE is obvious.

Band structures and the AVHE. The schematic band structures and the sketch of the field-controlled AVHE in the hole-doped antiferrovalley bilayer under a a positive and b negative perpendicular electric field. Green arrows show the direction of the vertical E field. Optical selection rules (see the Supplementary Material, Sec. IV for details) for the top VB are plotted as well

Through slightly p-type doping with Fermi energy lying between the VB edge of two monolayers, the Hall effect in the bilayer with the existence of a perpendicular electric field is also discussed. When the applied E field is positive (bottom panel of Fig. 2a), the majority carriers, i.e., spin-up holes from K σ − valley of the lower monolayer, acquire anomalous velocities proportional to the positive Berry curvatures and then accumulate in the right side of the sample. The combination of valley, spin and charge accumulations in such case, similar to the one reported in ferrovalley 2H-VSe2 monolayer,25 manifesting the presence of AVHE here. When the electric field is reversed (Fig. 2b), because of their negative Berry curvatures, spin-down holes of the upper layer, as net carriers, flow towards the left boundary, which obviously leads to the measurable transverse voltage with opposite sign.

Discussion

Previous analysis starting from the minimal k·p model propose the feasibility of governing the energetically valley degeneracy and eventually the AVHE utilizing a vertical electric field in the antiferrovalley bilayer. Using the bilayer VSe2 as an example, density-functional theory (DFT) calculations are carried out to confirm it.

As we expected, first-principles calculations show that total energy for the antiferromagnetic configuration is relatively lower than the ferromagnetic one, implying the antiferrovalley ground state for bilayer VSe2. We also consider the impact of valley-alignment. Our results prove that H-type stacking is the most stable case.

For the antiferrovalley bilayer, due to the interlayer antiferromagnetic configuration, spin-up and spin-down subbands are originally overlapped (see the middle panel in Fig. 3b). The VB maxima located at the point K + are comprised by \(\left( {\left| {{d_{{x^2} - {y^2}}}} \right\rangle + i\left| {{d_{xy}}} \right\rangle } \right){\rm{/}}\sqrt 2\) states of cation in lower layer and \(\left( {\left| {{d_{{x^2} - {y^2}}}} \right\rangle - i\left| {{d_{xy}}} \right\rangle } \right){\rm{/}}\sqrt 2\) ones from upper layer’s V atom. These two states, although occupied in momentum space uniformly, are with different symmetry, and thus correspond to opposite valley index. On the basis of the conservation of overall azimuthal quantum number,19 it can be easily deduced that states from the lower layer should be excited by left-handed radiation, namely K σ + valley states. Although the upper layer ones are related to right circularly polarized light, indicating the valley K σ − states. Note that, in absence of an electric field, band structures demonstrate the spin degeneracy, as well as the valley doublet.

Charge density difference, band structures, and Berry curvatures. a Charge density difference of H-stacking VSe2 bilayer between nonzero and zero external field with electron depletion shown in blue and electron accumulation in red. b Electric field-dependent band structures near points K ±. Solid lines are gained from first-principles calculations. Open triangles are the results from our minimal k·p model. Upward-pointing (Downward-pointing) triangles correspond to electronic states from lower (upper) monolayer. The Fermi level is set to zero in each cases. The applied electric field is with the magnitude of 0.1 V/Å. c Contour maps of Berry curvatures at valleys near the top VB with various electric field in units of Å2

After applying an out-of-plane electric field with the magnitude of 0.1 V/Å, the disequilibrium of electrostatic potential generates across the bilayer, which leads to electronic charge transfer from one to the other layer (Fig. 3a). In addition, as illustrated in left and right panels of Fig. 3b, the electric potential difference makes the states originated from one monolayer shift upward. Yet, the other layer atoms contribute to the opposite behavior. The decoupled band structures clearly elucidate the lifting of both spin and valley degeneracy in the bilayer.

We would like to point out that in VSe2 bilayer, the relatively small but non-negligible SOC effect couples with strong exchange interaction, making its band structures quite different from the representative ones displayed in Figs. 1 and 2. Nevertheless, they coincide with each other in essence. We further compare the band structures obtained from the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) with the DFT results. Table S3 in the Supplementary Material lists all the values of parameters we adopted here. The excellent agreement in Fig. 3b warrants the validity of our minimal k·p model to describe the electronic states in the neighborhood of points K ± for antiferrovalley TMDs bilayers.

Through calculating z-component Berry curvatures from the Kubo-formula,34 the influence of a perpendicular electric field on the Hall effect for a p-type bilayer (with Fermi level shown as violet dashed lines in Fig. 3b) is inspected. Although the global top of the VB is located in the Γ point, the carriers around there possess almost zero Berry curvatures and therefore are not considered in our analysis below.

As shown in Fig. 3c, in the absence of electric fields, the majority carriers, i.e., spin-down holes from the valley K σ + of the lower layer and K σ − spin-up holes of the upper monolayer, acquire opposite transverse velocities because of their opposite Berry curvatures in the same magnitude. Then, they move to different sides. The long lived spin and valley accumulations on sample boundaries in the Hall bar geometry demonstrate the existence of the VHE. More interestingly, a perpendicular electric field introduces additional charge Hall current. Net carriers derived from an individual valley accumulate in a single side of the ribbon, leading to a measurable transverse voltage. The combination of spin, valley and charge accumulations here implies the AVHE induced by electric fields. Furthermore, the sign of the Hall voltage depends strongly on the direction of the applied field. When the applied electric field is reversed, the valley index of the majority carriers would be opposite. The reverse sign of Berry curvatures causes their accumulations on the other boundary. Then, the transverse Hall voltage would be opposite. Antiferrovalley VSe2 bilayer thus presents an electrically tunable system for the AVHE.

To summarize, our theoretical analysis reveal that the valley Hall effect naturally exists in pristine antiferrovalley bilayers with inversion symmetry, where the valley indexes are energetically degenerate. When a vertical electric field is applied, the valley degeneracy can be broken. The attractive AVHE spontaneously appears. More importantly, the sign of transverse Hall voltage related to the AVHE is strongly dependent on the gate voltage. As we know, the valley Hall effect predicted by Zhang et al.27 in bilayer graphene has been successfully observed in a non-local transport measurement.31 We strongly advocate experimental efforts on the more promising antiferrovalley VSe2 bilayer through similar strategies. The purely electrical driven and tuning AVHE demonstrates the feasibility for realizing all-electric valleytronic devices in such antiferrovalley bilayers, where the valley information can be controlled by the electric field and easily read out through the sign of the Hall voltage. When the volatile electric field is replaced by some ferroelectric substrates or even construct the antiferrovalley bilayer using polar TMDs,35 more exciting prospects of valleytronics for application in advanced information functional devices with advantage in nonvolatility are emerging.

Methods

The calculations of bilayer VSe2 are performed within DFT using the accurate full-potential projector augmented wave (PAW) method implemented in the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package36 and include SOC effect. The exchange-correlation potential is treated in Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof form37 of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with a kinetic-energy cutoff of 600 eV. A well-converged 18 × 18 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh centered at Γ are chosen in self-consistent calculations. The convergence criterion for the electronic energy is 10−6 eV and the structures are relaxed until the Hellmann–Feynman forces on each atom are less than 1 meV/Å. In our calculations, dispersion-corrected DFT-D2 method38 is adopted to describe the van der Waals interactions between individual layers. The external electric field is introduced by planar dipole layer method.39

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bibes, M. & Barthelemy, A. Multiferroics: towards a magnetoelectric memory. Nat. Mater. 7, 425–426 (2008).

Dong, S., Liu, J.-M., Cheong, S.-W. & Ren, Z. Multiferroic materials and magnetoelectric physics: symmetry, entanglement, excitation, and topology. Adv. Phys. 64, 519–626 (2015).

Ohno, H. et al. Electric-field control of ferromagnetism. Nature 408, 944–946 (2000).

Ramesh R. Electric field control of ferromagnetism using multi-ferroics: the bismuth ferrite story. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 372, 20120437 (2014).

Matsukura, F., Tokura, Y. & Ohno, H. Control of magnetism by electric fields. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, 209–220 (2015).

Tong, W.-Y., Fang, Y.-W., Cai, J., Gong, S.-J. & Duan, C.-G. Theoretical studies of all-electric spintronics utilizing multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 112, 467–477 (2016).

Sivadas, N., Okamoto, S. & Xiao, D. Gate-controllable magneto-optic Kerr effect in layered collinear antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 267203 (2016).

Cherifi, R. O. et al. Electric-field control of magnetic order above room temperature. Nat. Mater. 13, 345–351 (2014).

Ghidini, M. et al. Non-volatile electrically-driven repeatable magnetization reversal with no applied magnetic field. Nat. Commun. 4, 1453 (2013).

Garcia, V. et al. Ferroelectric control of spin polarization. Science 327, 1106–1110 (2010).

Pantel, D., Goetze, S., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Reversible electrical switching of spin polarization in multiferroic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 11, 289–293 (2012).

Heron, J. T. et al. Electric-field-induced magnetization reversal in a ferromagnet-multiferroic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217202 (2011).

Tokunaga, Y., Taguchi, Y., Arima T-h & Tokura, Y. Electric-field-induced generation and reversal of ferromagnetic moment in ferrites. Nat. Phys 8, 838–844 (2012).

Gong, S. et al. A new pathway towards all-electric spintronics: Electric-field control of spin states through surface/interface effects. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron 56, 232–244 (2013).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Zeng, H., Dai, J., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Cui, X. Valley polarization in MoS2 monolayers by optical pumping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 490–493 (2012).

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Cao, T. et al. Valley-selective circular dichroism of monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun. 3, 887 (2012).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Rycerz, A., Tworzydlo, J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Valley filter and valley valve in graphene. Nat. Phys 3, 172–175 (2007).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Xiao, D., Liu, G. B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Zhu, Z., Collaudin, A., Fauque, B., Kang, W. & Behnia, K. Field-induced polarization of Dirac valleys in bismuth. Nat. Phys 8, 89–94 (2012).

Tong, W.-Y., Gong, S.-J., Wan, X. & Duan, C.-G. Concepts of ferrovalley material and anomalous valley Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 13612 (2016).

Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Niu, Q. Valley-dependent optoelectronics from inversion symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. B 77, 235406 (2008).

Zhang, F., Jung, J., Fiete, G. A., Niu, Q. & MacDonald, A. H. Spontaneous quantum Hall states in chirally stacked few-layer graphene systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 156801 (2011).

Gorbachev, R. V. et al. Detecting topological currents in graphene superlattices. Science 346, 448–451 (2014).

Velasco, J. Jr. et al. Competing ordered states with filling factor two in bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 5, 4550 (2014).

Sui, M. et al. Gate-tunable topological valley transport in bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 11, 1027–1031 (2015).

Shimazaki, Y. et al. Generation and detection of pure valley current by electrically induced Berry curvature in bilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 11, 1032–1036 (2015).

Wu, S. et al. Electrical tuning of valley magnetic moment through symmetry control in bilayer MoS2. Nat. Phys 9, 149–153 (2013).

Lee, J., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Electrical control of the valley Hall effect in bilayer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 421–425 (2016).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Yao, Q.-F. et al. Manipulation of the large Rashba spin splitting in polar two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 95, 165401 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396–1396 (1997).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Neugebauer, J. & Scheffler, M. Adsorbate-substrate and adsorbate-adsorbate interactions of Na and K adlayers on Al(111). Phys. Rev. B 46, 16067–16080 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Project for Basic Research of China (Grant No. 2014CB921104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51572085), Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (No. 17JC1402500), and ECNU Outstanding Doctoral Dissertation Cultivation Plan of Action (No. PY2015048). Computations were performed at the ECNU computing center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-G.D. conceived the idea and supervised the work. W.-Y.T. carried out the k·p model and first-principles calculations, and did the data analysis. W.-Y.T. and C.-G.D. contributed to the interpretation of the results, co-wrote, reviewed, and modified the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, WY., Duan, CG. Electrical control of the anomalous valley Hall effect in antiferrovalley bilayers. npj Quant Mater 2, 47 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0051-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0051-6

This article is cited by

-

Proposal for valleytronic materials: Ferrovalley metal and valley gapless semiconductor

Frontiers of Physics (2024)

-

Janus monolayer TaNF: A new ferrovalley material with large valley splitting and tunable magnetic properties

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Anomalous valley Hall effect in antiferromagnetic monolayers

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)

-

Valleytronics in transition metal dichalcogenides materials

Nano Research (2019)

-

Valleytronics in thermoelectric materials

npj Quantum Materials (2018)