Abstract

Quantum anomalous Hall insulators, which display robust boundary charge and spin currents categorized in terms of a bulk topological invariant known as the Chern number (Thouless et al Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982)), provide the quantum Hall anomalous effect without an applied magnetic field. Chern insulators are attracting interest both as a novel electronic phase and for their novel and potentially useful boundary charge and spin currents. Honeycomb lattice systems such as we discuss here, occupied by heavy transition-metal ions, have been proposed as Chern insulators, but finding a concrete example has been challenging due to an assortment of broken symmetry phases that thwart the topological character. Building on accumulated knowledge of the behavior of the 3d series, we tune spin-orbit and interaction strength together with strain to design two Chern insulator systems with bandgaps up to 130 meV and Chern numbers C = −1 and C = 2. We find, in this class, that a trade-off between larger spin-orbit coupling and strong interactions leads to a larger gap, whereas the stronger spin-orbit coupling correlates with the larger magnitude of the Hall conductivity. Symmetry lowering in the course of structural relaxation hampers obtaining quantum anomalous Hall character, as pointed out previously; there is only mild structural symmetry breaking of the bilayer in these robust Chern phases. Recent growth of insulating, magnetic phases in closely related materials with this orientation supports the likelihood that synthesis and exploitation will follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The honeycomb lattice,1,2 particularly in conjunction with its Dirac points and two-valley nature in graphene,3 has provided the basic platform for a great number of explorations into new phases of matter and new phenomena. Yet the single band, uncorrelated case of graphene is only the simplest level of what can be realized on honeycomb lattices. The recognition that a perovskite (111) bilayer of LaXO3 encased in LaAlO3 (we use the notation 2LXO for an X bilayer, X=transition metal [TM]) provides a honeycomb lattice that led to a call for engineering ( i.e., design) of a Chern insulator in such systems.4,5 The origin of the buckled honeycomb lattice is depicted in Fig. 1. A number of model6,7,8,9 and material-specific studies10,11,12,13,14,15,16 have probed the possibilities that such systems may offer. The advent of (111)-oriented growth of oxides17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 provides a new platform for design of new materials, and especially Chern insulators.

The degree of generalization from graphene is huge. Graphene has a hopping amplitude, or equivalently a velocity, that sets the energy scale, and a two-valley degree of freedom. 2LXO, on the other hand, presents a multi-orbital system with a number of additional degrees of freedom: intraatomic Coulomb repulsion U and Hund’s rule spin interaction J H , cubic crystal field splitting Δ cf , trigonal crystal field splitting δ cf , spin-orbit coupling (SOC) strength ξ, orbital-dependent interatomic hopping amplitudes, and band filling n d . Altogether, these couple to the lattice to provide two more scales, the Jahn-Teller (λ JT ) and breathing (λ br ) distortion strengths. This list includes more than ten parameters, and the treatment of them from a model Hamiltonian viewpoint, even within mean field, is formidable. Some of these energy scales have been included in model studies,9 but the coupling to lattice that we find to be a determining factor is too intricate for model Hamiltonian studies. Interplay of U with large SOC fulfills the requirements of proposed Chern Mott insulators with bandgaps an order of magnitude larger than those studied so far.

An efficient design strategy must seek to identify promising candidates. The density functional theory (DFT) approach is able to treat all the complexities mentioned above straightforwardly as a part of the electronic structure problem, including other factors such as Madelung potential effects. Also, requiring the choice of atoms from certain classes in the periodic table reduces the scope of the design process from a continuous ∼10 dimensional space to a Diophantine set, and presents clear opportunities to experimentalists. For specific realizations (here, atom X) the many energy scales are known or determined self-consistently. DFT+U treatment requires examination of a few types of likely order parameters (charge, spin, orbital, structural), but the possibilities are also constrained by the vast accumulated knowledge of how TM ions behave in oxides, so the computational complexity becomes manageable. Dynamical correlations may need to be incorporated separately, but they are unrealistic without detailed input from DFT on the symmetry-broken ground states.12

Is there a “design” in this system that can be efficient and effective? Two of the current authors have carried out a systematic study of the entire sequence of 3d TM ions on this buckled honeycomb lattice.14 In three cases X = Ti, Mn, and Co, a Chern insulating phase was obtained as U was varied and the structure relaxed,14 but the combination of relatively large U∼5 eV and accompanying symmetry-breaking distortion resulted in trivial Mott insulating ground states. A lively interplay also was observed between pseudocubic local symmetry (each cation lies within an octahedron of six O ions) and global trigonal symmetry of the ideal lattice.12,14

These studies however provided important guidance for design of Chern phases in buckled honeycomb lattices. The emerging design principles became: (a) focus on systems that promote a Dirac point at K in the symmetric phase, (b) avoid large symmetry-breaking effects such as the Jahn-Teller distortions that destroyed the Chern phases in the 3d systems, (c) vary the strain, as electronic configurations are sensitive to strain, and (d) increase the SOC strength, as it extends the band entanglement over a proportionately greater energy and can be expected to retain entanglement with larger gap. Item (a) is the underlying feature that has made this system such a promising one.4 Item (b) indicates that the repulsion U, which also tends to enforce anisotropic, Jahn-Teller-active ions, should be decreased from the 3d value. Item (c), sensitivity to strain, has been found in many studies to influence electronic configurations at interfaces, with its influence on topological nature yet to be quantified. Item (d) is widely postulated, making 5d systems the focus of searches for Chern insulators. We have applied these design principles to explore 4d and 5d 2LXO bilayers, finding Chern insulating ground states for both the osmate and the ruthenate members, with gaps up to 30 times larger than previously designed TMO Chern insulators: ultrathin VO2 26,27 and CrO2 28 layers with calculated gaps of 2 meV and 4 meV respectively.

Interest in 5d ions on the honeycomb lattice has focused primarily on the Ir ion,10,11,18,21 which is not a part of this study. We consider specifically the 3d→4d→5d sequence of ions; for d 4: Mn, Tc, Re; for d 5: Fe, Ru, Os. With the considerable changes vs. size and chemistry of the TM ion, we have found that the favorable cases shift from one column (d 4) to the next (d 5) in the periodic table. 2LOsO, with smallest U and largest SOC, might be the first guess as the most promising candidate. Unexpectedly, we find that the intermediate 4d Ru ion provides the most promising candidate of Chern insulator in this structural class.

For SrIrO3 iridates (also d 5), there are competing indications whether the bilayer perovskite platform will be both ferromagnetic (FM) and insulating as required for a Chern insulator, or rather will assume some less desirable configuration.10,17,22 It is highly encouraging that (111)-grown SrIrO3 and (Ca,Sr)IrO3 have been synthesized, with the former found to be magnetic and insulating.18,22 We provide below detailed predictions that, once all effects are accounted for, 2LRuO and 2LOsO buckled honeycomb lattices will be Chern insulators with substantial gaps.

Results

DFT+U calculations (see the Materials and Methods section and Ref. 14) have been performed for the 4d candidates X = Tc and Ru, and the 5d examples X = Re and Os, in the Mn d 4 and Fe d 5 columns respectively. Two in-plane lattice constants are considered, LaAlO3 (LAO) denoted a LAO (3.79 Å) and LaNiO3 (LNO) denoted a LNO (3.86 Å), differing by only 1.8%, still this amount of strain is found to tip the balance between Chern and trivial ground states. Previous DFT studies on Os based oxide compounds adopted values of U in the range 0.8–3 eV.25,29,30,31 We use U Os = 1 eV, U Ru = 3 eV, U Fe = 5 eV, and find that results are not very sensitive to reasonable variations around these values. The data in Table 1 include those for low spin S = 1/2 Fe, for comparison with Ru and Os. The low spin Fe configuration is 0.5–0.6 eV higher in energy than the high spin state depending on strain, and both FM configurations are higher in energy than the AFM ground state discussed previously.14 Whereas the high spin ion is spherically symmetric (hence not subject to Jahn-Teller distortion), the low spin state will be more susceptible to structural change.

Substantial differences due to transition metal size and chemistry are evident. In the 3d series, 2LMnO provided the most instructive example, by transforming from a Chern insulator phase to a trivial insulator, during which a JT distortion closes the Chern gap and then reopens a trivial gap. The isovalent partners X = Tc and Re can be dismissed. Tc3+ is FM but with considerable band overlap, while we did not find Re3+ to support magnetism in these bilayers.

Moving to the d 5 column (see Table 1), low spin FM 2LFeO is a trivial insulator with a large gap ∼2.5 eV for both values of strain. The low spin configuration is 0.4–0.5 eV/Fe higher in energy than the high spin state, hence unlikely to be synthesized. We find that, unlike 2LFeO, 4d 2LRuO and 5d 2LOsO do not support a high spin state, due to weaker correlation effects than those that occur in Fe. The resulting single hole in the low spin \({t}_{{2}_{g}}\) subshell reduces the orbital occupation complexity compared to the two-hole d 4 ions, but still shows important flexibility because the trigonal crystal field splitting of \({a}_{{1}_{g}}\) and \({e}_{g}^{^{\prime} }\) is sensitive to the strain provided by the substrate. The smaller exchange splitting of the low spin ion promotes the tendency to topological entanglement: by lessening the energy separation between opposite spin bands, SOC can enforce stronger entanglement.

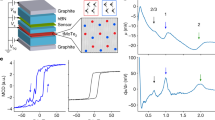

For both Os and Ru, and for both lattice constants considered, restricting symmetry to P321 (i.e., symmetry equivalent X sites) and including SOC led to Chern insulating phases, as for the 3d cases X=Ti, Mn, and Co.14 With the open d shell and the spectrum being gapped by U, these are FM Chern Mott insulators. We restrict our discussion now to the relaxed, symmetry broken (inequivalent X sites) ground states,12,14 confirming the earlier results in the 3d series that full relaxation is essential to make realistic predictions. The basic ground state data, including that of low spin Fe for contrast, are provided in Table 1. Figure 2 presents the band structures for 2LOsO and 2LRuO, first without (left panels) and then with SOC (right panels), for both values of the in-plane lattice constant.

Top four panels: band structures of the fully relaxed buckled bilayers corresponding to lattice constant a LAO, for both 2LOsO and 2LRuO. Majority and minority bands are plotted in blue and yellow, respectively. Left panels, before including SOC; right panels, with SOC included. Lower four panels, analogous plots for a LNO. Note that SOC converts the half metallic FM spectrum for 2LOsO to the gapped Chern insulator C = 2 phase

The Os3+ formal valence state, as in LaOsO3, is known as an unstable valence state for solid state synthesis, and LaOsO3 is not a reported compound. However, epitaxial methods have been established to enable synthesis of several layers of materials that cannot be grown in thermodynamic conditions. LaRuO3, on the other hand, has been grown by both solid state32 and epitaxial33,34 methods since earlier reports of bulk synthesis.35,36 Since LaRuO3 is relatively little studied, it offers an additional opportunity of adding another compound to the family of important transition metal oxides (Fig. 3).

The orbital moments of the Os1 and Os2 ions are similar, 0.19 μ B for a LAO decreasing to 0.14 μ B for a LNO. Spin mixing by SOC reduces the total spin moment to 1.5 ± 0.1 μ B. The gapless band structure for a LNO becomes gapped to 46 meV for a LAO, and the Chern number C = 2 establishes that the desired Chern insulating state has been found. As shown in Fig. 2, not only is 2LOsO metallic before SOC is included, but a narrow peak in the DOS at E F (see the Supplemental Information) reflects a flat band region nearly coinciding with the Fermi level. For the 3d series, SOC leaves bands mostly intact, only opening gaps at the Dirac point and quadratic band touching points, and opening anticrossings. In 2LOsO, SOC is very large and, as mentioned, bands before SOC cannot be lined up by eye with bands after SOC, i.e., entanglement is extensive. Thus for 5d ions, gaps are opened by widespread band rearrangements rather than by simple anticrossings. For 2LOsO, a very significant effect of the substrate lattice constant is that the distance between Os1 and Os2 layers, 2.52 Å for a LAO, reduces to 2.40 Å for a LNO.

Chandra and Guo37 have considered several 4d and 5d ions in this same buckled honeycomb lattice, encased in either LAO or SrTiO3, including Os but not Ru. In their studies the lattice was restricted to trigonal symmetry, and using GGA (generalized gradient approximation for the functional) only rather than GGA+U. The one Chern insulator they reported was this same 2LOsO bilayer, with a similar band structure near the gap and even a similar gap although restricted to P321 symmetry. The similarity of their results to ours provides evidence that these predictions for a relatively mildly correlated materials are not highly sensitive to theoretical choices. Chandra and Guo did not, however, vary the strain and discover the strong strain dependence of the Chern insulating character.

2LaRuO3

For 2LRuO at a LAO without SOC, Figure 2 shows a tiny gap along Γ−M near M, and an evident band inversion at M but apparently not at M′ where there is a substantial gap. After SOC, the FM insulating state is preserved but trivial, so the apparent band inversion is not effective in producing a topological phase. The a LNO case is the most interesting. The half metallic FM band structure becomes, upon including SOC, a C = −1 Chern insulator with a 132 meV gap. The spin direction is along the \(\hat{c}\)-axis (cubic [111] direction), for which the energy is 22 meV/Ru less than for spin oriented in-plane. For comparison, the larger SOC of Os results in a larger MAE of 37 meV in its Chern phase. Conversely, the smaller SOC of Fe results in orbital moments and MAE an order of magnitude smaller than in Ru.

The main change in orbital occupation upon rotation into the plane is the transfer of 0.06 electrons from m = −2 to m = +2 orbitals. Since the quantization of these orbitals is with respect to cubic [111], this change is not directly related to the orbital moment for spin in-plane. Note, both from the data in Table 1 and the near symmetry of K and K′, and M and M′, in the final bands in Fig. 2 that, as for 2LOsO, the Chern phase is very modestly distorted from P321 symmetry. Notably, the magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE) is almost an order of magnitude smaller (3 meV) for 2LRuO at the smaller LAO lattice constant (C = 0) where the sublattice symmetry is more strongly broken (see Table 1). The larger MAE can be attributed to the retention of \({e}_{g}^{^{\prime} }\) quasi-degeneracy in the nearly symmetric Chern phases, which contributes to large anisotropy.38

The separation Δz M,M′ = 2.42 ± 0.01 Å of Ru layers in 2LRuO depends only weakly on the substrate lattice constant. At a LNO, the Ru1-Ru2 inequivalence is small so the difference in orbital moments is minor, and the spin moment is hardly reduced by SOC. Before SOC is included a peak in the DOS (see Supplementary Information) lying at E F appears as for 2LOsO at a LAO. The band giving rise to the peak is shifted by SOC (see below), resulting in a gap of 132 meV and a C = −1 Chern insulating phase. For 2LRuO at a LAO, the two Ru sites show larger differences in orbital moments, 0.08 vs. 0.16 μ B, see Table 1. SOC opens a large gap of 150 meV, but to a trivial insulator state. This last result suggests that the larger gap makes it impossible to sustain the band inversion and spin entanglement that is needed for the QAH phase.

The Berry curvatures \({\Omega }_{z}(\overrightarrow{k})\) of the two sister Chern bilayers, pictured in Fig. 4, reflect very different distributions (as well as opposite signs). 2LOsO contains high and narrow peaks, distributed almost symmetrically around the K points along lines toward the three neighboring M points. The peaks lie near the minimum gap, a common occurrence. For 2LRuO, the seemingly minor breaking of three-fold symmetry becomes very obvious in Ω z . The most intense peak arises near one M point, just off the M−Γ line, and a secondary peak occurs in a similar position relative to the M′ point. The fraction of area that contributes to C = −1 is considerably larger in 2LRuO than that leading to C = 2 in 2LOsO.

Discussion

Both 2LOsO and 2LRuO exhibit the sought-for Chern insulator (quantum anomalous Hall) state, with Chern numbers and gaps C = 2, 46 meV and C = −1, 132 meV, respectively, occurring for different choices of substrate. The magnitude of C suggests a guideline that larger values result from larger moments and strong SOC, as long as topological character can be maintained.39 The strong dependence on lateral strain demonstrates that strain offers a means to manipulate Chern insulating phases as well as to engineer other properties, such as the Fermiology and superconductivity in Sr2RuO4 thin films.40 For both Os and Ru, larger orbital moments arise in the Chern phase than in the trivial state. Figure 3, emphasizing the bands of \({a}_{{1}_{g}}\) character (the rest of the character is \({e}_{g}^{\prime}\)) illustrates critical effects of strain. Strain interchanges \({a}_{{1}_{g}}\) with \({e}_{g}^{\prime}\) character of the hole dramatically, and in both cases it is the one with strong \({a}_{{1}_{g}}\) hole character that promotes the Chern insulating phase. This result is consistent also with the observation that the Chern phases incur much less distortion than the trivial phases, because an \({a}_{{1}_{g}}\) hole is nondegenerate.

Additional regularities can be observed. Both 2LOsO@a LNO and 2LRuO@a LAO in Fig. 2, before accounting for SOC, show an uppermost occupied band lying at E F that is flat over much of the zone. These are the cases with smaller orbital moments and they have larger gaps once SOC is included, and they are also the trivial insulating states. The other two cases—the Chern phases—are mildly symmetry broken from threefold symmetry. The Dirac point at K in the unoccupied bands of 2LRuO is hardly gapped at all, and the orbital moments of the two sites are identical. In this way they resemble their 3d counterparts X = Ti, Mn, Co for imposed threefold symmetry. The spectrum is topological, but when symmetry is broken more strongly, entanglement is lost. This result is what our “pre-design” (on the series of 3d ions) had led us to conclude.14 A significant new result is that the topological nature can be tuned with even a modest amount of strain.

Our main result is that the Ru buckled honeycomb layer provides, after full relaxation, a QAH (Chern) insulator with a gap of 132 meV. Secondarily, the isovalent Os bilayer provides a Chern insulating state with a gap of 46 meV. The calculated anomalous Hall conductivities correspond to Chern numbers C = −1 and C = +2, respectively.

As mentioned in the Introduction, strong interaction U, large SOC ξ, and strain and the associated local symmetry are coupled in their impact. A schematic phase diagram is presented in Fig. 5 in (strain,U,ξ) space. Isovalent Ru and Os lie along a line of probable Chern phases, as pictured. However, since the Chern number changes between the established points, either (1) the gap must close and then re-open with a different Chern number, or (2) a first-order phase transition must occur, which cannot be foreseen without an accurate theory of the free energy. Ru-Os alloy bilayers evidently provide a rich region for further study. Fortunately, high quality (111) film growth of this kind has been reported for iridates,18,22 making synthesis and applications with Os and Ru quite promising. We hope that these results will stimulate intense experimental study of these materials.

Materials and Methods

The design of these Chern insulating phase has built upon earlier trend studies of the corresponding 3d series of buckled bilayers,14 with indications of Chern phases first observed in the study of the nickelate system.13 The sensitivity to the local environment had been observed in the study of the corresponding titanate system.12 The extension to 4d and 5d ions naturally indicated the use of the same DFT-based electronic structure methods. The Wien2k code,41 based on a general potential, all-electron linearized augmented plane wave basis set, forms the basis of our computational method. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA)42 was chosen for the exchange-correlation functional, supplemented by mean-field electronic correlations as described by the GGA+U functional.43 In line with earlier work on the corresponding bulk oxides, the intra-atomic repulsion strengths were chosen as U Os = 1 eV, U Ru = 3 eV, and Hund’s coupling J = 0.5 eV was used for both. The values for Fe were U Fe = 5 eV, J = 0.7 eV. U = 8 eV on the La 4f orbitals is applied to displace them upward somewhat, in line with what is observed in inverse photoemission data. The computational results were found to be robust with respect to reasonable variations of the onsite Coulomb repulsion strength.

The influence of strain was investigated by setting the lateral lattice constant separately to those of LAO and LNO, a LAO = 3.79 Å or a LNO = 3.86 Å, simulating superlattices grown either on an LAO(111) substrate, or an LNO substrate with +1.8% relative strain. The out-of-plane lattice parameter c was first chosen to be that of (LaNiO 3)2/(LaAlO 3)4(111) studied by Doennig and co-authors13, then the c lattice parameter was optimized and the atomic coordinates were relaxed to minimize the energy, consistent with the imposed symmetry. Specifically, octahedral tilts and distortions were allowed when obtaining the final results. Calculations were first done with symmetry constrained to space group P321 (threefold rotation plus inversion), then unconstrained to P1 symmetry (no symmetry) to obtain full relaxation.

A 20 × 20 × 6 k-point mesh was used for self-consistency. Structural relaxations were carried out with SOC included. SOC was also included in the electronic properties calculations with (001) as the spin direction (and also with in-plane spin direction, to obtain the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy). Subsequently we used Wannier interpolation based on maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs) to calculate the Berry curvature and the anomalous Hall conductivity, and thereby to obtain the Chern number.44,45,46

The Bloch wave functions were projected onto the d local orbitals of Os, Ru, or Fe to obtain MLWFs,44 which serve as the basis for further analysis. The MLWF-interpolated energy bands are in excellent agreement with the Wien2k bands. The Berry curvature Ω z (k) is obtained from all bands below the Fermi level beginning from the definition

and performing manipulations required by the use of a finite set of MLWFs.45 The Berry curvature is integrated over the Brillouin zone to obtain the anomalous Hall conductivity using

where σ xy = −σ yx is the antisymmetric part of the conductivity. The Chern numbers were computed by sampling a dense k-point grid of 300 × 300 × 50.

References

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a quantum hall effect without landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015–2018 (1988).

Castro Neto, H. H., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109–162 (2009).

Xiao, D., Zhu, W., Ran, Y., Nagaosa, N. & Okamoto, S. Interface engineering of quantum hall effects in digital transition metal oxide heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 2, 596 (2011).

Wright, A. R. Realising Haldane’s vision for a Chern insulator in buckled lattices. Sci. Rep 3, 2736 (2013).

Rüegg, A. & Fiete, G. A. Topological insulators from complex orbital order in transition-metal oxides heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 84, 201103 (2011).

Yang, K.-Y. et al. Possible interaction-driven topological phases in (111) bilayers of LaNiO3. Phys. Rev. B 84, 201104(R) (2011).

Rüegg, A., Mitra, C., Demkov, A. A. & Fiete, G. A. Electronic structure of (LaNiO3)2/(LaAlO3) N heterostructures grown along [111]. Phys. Rev. B 85, 245131 (2012).

Okamoto, S. Doped mott insulators in (111) bilayers of perovskite transition-metal oxides with a strong spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 066403 (2013).

Lado, J., Pardo, V. & Baldomir, D. Ab initio study of Z 2 topological phases in perovskite (111) (SrTiO3)7(SrIrO3)2 and (KTaO3)7(KPtO3)2 multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 88, 155119 (2013).

Okamoto, S. et al. Correlation effects in (111) bilayers of perovskite transition-metal oxides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 195121 (2014).

Doennig, D., Pickett, W. E. & Pentcheva, R. Massive symmetry breaking in LaAlO3/SrTiO3(111) quantum wells: a three-orbital, strongly correlated generalization of graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 126804 (2013).

Doennig, D., Pickett, W. E. & Pentcheva, R. Confinement-driven transitions between topological and mott phases in (LaNiO3) N /(LaAlO3) M (111) superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 89, 121110 (2014).

Doennig, D., Baidya, S., Pickett, W. E. & Pentcheva, R. Design of Chern and Mott insulators in buckled 3d oxide honeycomb lattices. Phys. Rev. B 93, 165145 (2016).

Weng, Y., Huang, X., Yao, Y. & Dong, S. Topological magnetic phase in LaMnO3 (111) bilayer. Phys. Rev. B 92, 195114 (2015).

Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Interaction-induced quantum anomalous Hall phase in (111) bilayer of LaCoO3. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125139 (2015).

Chen, Y. & Kee, H.-Y. Topological phases in iridium oxide superlattices: quantized anomalous charge or valley Hall insulators. Phys. Rev. B 90, 195145 (2014).

Hirai, D., Matsuno, J. & Takagi, H. Fabrication of (111)-oriented Ca0.5Sr0.5IrO3/SrTiO3 superlattices—a designed playground for honeycomb physics. APL Matl 3, 041508 (2015).

Matsuno, J. et al. Engineering a spin-orbital magnetic insulator by tailoring superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 247209 (2015).

Jia, Y. et al. Exchange coupling in (111)-oriented La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/La0.7Sr0.3FeO3 superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 92, 094407 (2015).

Nie, Y. F. et al. Interplay of spin-orbit interaction, dimensionality, and octahedral rotations in semimetallic SrIrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 016401 (2015).

Anderson, T. J. et al. Metastable honeycomb SrTiO3/SrIrO3 heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 151604 (2016).

Jia, Y. et al. Thickness dependence of exchange coupling in (111)-oriented perovskite oxide superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104403 (2016).

Kim, T. H. et al. Polar metals by geometric design. Nature 533, 68–72 (2016).

Middey, S., Debnath, S., Mahadevan, P. & Sarma, D. D. NaOsO3: a high Neel temperature 5d oxide. Phys. Rev. B 89, 134416 (2014).

Huang, H., Liu, Z., Zhang, H., Duan, W. & Vanderbilt, D. Emergence of a Chern-insulating state from a semi-Dirac dispersion. Phys. Rev. B 92, 161115(R) (2015).

Pardo, V. & Pickett, W. E. Half-metallic semi-dirac point generated by quantum confinement in TiO2/VO2 nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 166803 (2009).

Cai, T. et al. Single-spin Dirac Fermion and Chern insulator based on simple oxides. Nano Lett. 15, 6434–6439 (2015).

Pardo, V. & Pickett, W. E. Compensated magnetism by design in double perovskite oxides. Phys. Rev. B 80, 054415 (2009).

Xiang, H. J. & Whangbo, M. H. Cooperative effect of electron correlation and spin-orbit coupling on the electronic and magnetic properties of Ba2NaOsO6. Phys. Rev. B 75, 052407 (2007).

Gangopadhyay, S. & Pickett, W. E. Spin-orbit coupling, strong correlation, and insulator-metal transitions: The J eff = 3/2 ferromagnetic Dirac-Mott insulator Ba2NaOsO6. Phys. Rev. B 91, 045133 (2015).

Sugiyama, T. & Tsuda, N. Electrical and magnetic properties of Ca1−x La x RuO3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 68, 3980–3987 (1999).

Kimura, M., Ito, A., Kimura, T. & Goto, T. Preparation of LaRuO3 films by microwave plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Thin Solid Films 520, 1847–1850 (2012).

Labhsetwar, N. K., Watanabe, A. & Mitsuhashi, T. New improved syntheses of LaRuO3 perovskites and their applications in environmental catalysis. Appl. Catalysis B 40, 21–30 (2003).

Bouchard, R. J. & Weiher, J. F. La x Sr1−x RuO3: a new perovskite series. J. Solid State Chem. 4, 80–86 (1972).

Kobayashi, H., Nagata, M., Kanno, R. & Kawamoto, Y. Structural characteriation of the orthorhombic perovskites: [ARuO3 (A=Ca, Sr, La, Pr)]. Mat. Res. Bull. 29, 1271–1280 (1994).

Chandra, H. K. & Guo, G. Y., Topological insulator associated with quantum anomalous Hall phase in ferromagnetic perovskite superlattices, arXiv:1512.08843.

Ou, X., Wang, H., Fan, F., Li, Z. & Wu, H. Giant magnetic anisotropy of Co, Ru, and Os adatoms on MgO (001) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 257201 (2015).

Wang, J., Lian, B., Zhang, H., Xu, Y. & Zhang, S. C. Quantum anomalous Hall effect with higher plateaus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 136801 (2013).

Burganov, B. et al. Strain control of fermiology and many-body interactions in two-dimensional ruthenates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 197003 (2016).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Madsen, G. K. H., Kvasnicka, D. & Luitz, J. WIEN2k, An Augmented Plane Wave Plus Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties. (Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2001). ISBN 3-9501031-1-2.

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Ylvisaker, E. R., Koepernik, K. & Pickett, W. E. Anisotropy and magnetism in the LSDA+U method. Phys. Rev. B 79, 035103 (2009).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685–699 (2008).

Wang, X., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Ab initio calculation of the anomalous hall conductivity by Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195118 (2006).

Kuneš, J. et al. Wien2wannier: From linearized augmented plane waves to maximally localized Wannier functions. Comp. Phys. Commun 181, 1888–1895 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge helpful discussions with D. Arovas, A. Essin, K. Koepernik, K. L. Lee, V. Pardo, and Y. Quan. Funding: The calculations were performed in Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at the PNNL and National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). NERSC is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council and the NSFC 21373190 (H.G.), by the German Science Foundation within SFB/TR80, project G3 (R.P.), and by US National Science Foundation Grant DMR-1534719 (W.E.P.) under the Designing Materials to Engineer and Revolutionize our Future program.

Author contributions

This project was conceived by W.E.P. and R.P., and supervised by W.E.P. Calculations were carried out on the Ru and Os systems by H.G., with important assistance provided by S.G. O.K. performed the calculations on the Fe systems, overseen by R.P. All authors contributed to the analysis, and W.E.P. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, H., Gangopadhyay, S., Köksal, O. et al. Wide gap Chern Mott insulating phases achieved by design. npj Quant Mater 2, 4 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-016-0007-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-016-0007-2

This article is cited by

-

High Chern numbers in a perovskite-derived dice lattice (LaXO3)3/(LaAlO3)3(111) with X = Ti, Mn and Co

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Chern insulator with a nearly flat band in the metal-organic-framework-based Kagome lattice

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Chern and Z2 topological insulating phases in perovskite-derived 4d and 5d oxide buckled honeycomb lattices

Scientific Reports (2019)