Abstract

Matter-wave interferometer of ultracold atoms with different linear momenta has been extensively studied in theory and experiment. The vortex matter-wave interferometer with different angular momenta is applicable as a quantum sensor for measuring the magnetic field, rotation, geometric phase, etc. Here we report the experimental realization of a vortex matter-wave interferometer by coherently transferring the optical angular momentum to an ultracold Bose condensate. We use the angular interference technique to measure the relative phase of two vortex states. For a lossless interferometer with atoms only populating two spin states, the difference between the relative phases in the two spin states is locked to π. We also prove the robustness of this out-of-phase relation, not sensitive to the angular-momentum difference between two vortex states, constituent of Raman optical fields and expansion of the condensate. The experimental results agree well with the calculation from the unitary evolution of wave packet in quantum mechanics. This work opens a new way to build a quantum sensor based on the vortex matter-wave interference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interference is fundamental to wave dynamics and quantum mechanics. Interferometry represents a unique way to probe the subtle changes of physical parameters by precisely measuring the resultant tiny relative phase shifts. Matter-wave interferometry, especially those realized in ultracold atomic gases, opens a pathway to extract the relative phase between coherent constituents traversing different paths, and holds promise for applications in both practical precision measurement and fundamental quantum research1. Like the original optical interferometer where beam splitter (BS) plays a central role, a variety of matter-wave interferometers have emerged employing different mechanisms to realize coherent splitting and recombination of the wavepackets, including double-well potential2,3, Bragg scattering4, optical lattice5, and Stern–Gerlach separation6,7, to name a few. As mentioned above, matter-wave interferometer of ultracold atoms with different linear momenta has been extensively studied in theory and experiment. Another type of fundamental matter-wave interferometer would be a vortex matter-wave interferometer with different orbital angular momenta (OAMs). This proposal could be implemented by transferring the OAM of the laser beam to cold atoms through the optical transition, thanks to the recent developments both in vortex light beam carrying definite OAM8,9,10 and its coherent interaction with cold atoms11,12,13,14.

Recently, the vortex matter-wave interferometer has been theoretically proposed to be applicable to measure the rotation, magnetic field, interatomic interaction, geometric phase, etc15,16,17,18,19,20. Two different vortex states accumulate different phases respect to an external rotation of the system, thus a compact and stable quantum gyroscope without BS and mirror is feasible using this scheme16,17,20. The two interfering vortex states can overlap at zero relative velocity, then the long interrogation time can enhance the measurement precision to extract the subtle interatomic interaction15,18,19. Furthermore, OAM states offer a high dimensional Hilbert space to obtain extra security and dense coding of quantum information21,22, providing the possibility of using the vortex-state superposition in quantum gases as qubit23,24. People have used the vortex interference patterns in ultracold atoms to measure the winding number of the vortex state11,12,25. However, the vortex matter-wave interferometer is yet to be explored, where the relative phase between the two interfering vortex states should be quantitatively determined.

Here we report the experimental realization of a vortex matter-wave interferometer in a two spin Bose–Einstein condensate. We measure the relative phase between the two vortex states by analyzing the angular interference fringes. A pair of Raman laser beams with an OAM difference as one BS produce the spin-dependent vortex states, and a radio-frequency (RF) pulse as another BS combines two different vortex states into one spin state. After producing two lossless BSs with atoms only populating two spin states, we demonstrate that the difference between the relative phases of vortex modes in the two spin states is shown to be constant (with a π-phase difference), irrespective of fluctuation in each spin state. This out-of-phase relation is robust, not sensitive to the angular-momentum difference between the two interfering vortex states, constituent of Raman optical fields, and expansion of the condensate.

Results

Scheme of the interferometer

The vortex matter-wave interferometer is schematically presented in Fig. 1a. The input vortex state with an OAM number l1 is in the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\) of the condensate, which can be denoted as \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\). The BS1, a two-photon Raman pulse composed of a pair of vortex laser beams, transfers the OAM difference of lights to atoms and produces the vortex state \(\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\) in the spin state \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\). After BS1, the input quantum state is split into two paths \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\). The BS2, an RF pulse transferring atoms back and forth between the two spin states, combines the two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\) in each spin state. After BS2, the quantum state can be denoted as \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle (\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle +{e}^{i{\phi }_{\uparrow }}\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle )+{e}^{i{\phi }_{0}}\left|\downarrow \right\rangle (\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle +{e}^{i{\phi }_{\downarrow }}\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle )\), where ϕ0 is the relative phase between the two spin state, ϕ↑ and ϕ↓ are the relative phases between the two vortex states in spin states \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\), respectively. Finally, a Stern-Gerlach magnetic field pulse makes a projection of the output quantum state onto the two spin states, i.e., the superposition state \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle +{e}^{i{\phi }_{\uparrow }}\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\) onto \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle +{e}^{i{\phi }_{\downarrow }}\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\)) onto \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\). The values of ϕ↑,↓ can subsequently be extracted from the interference patterns in the two spin states.

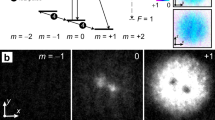

a The interferometer is composed of two BSs (BS1 and BS2). The input vortex state \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) is in the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\). The BS1 (a two-photon Raman pulse) splits the input state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) into two paths \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle \left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\). The BS2 (an RF pulse) combines two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\) in each spin state. ϕ↑ and ϕ↓ are the relative phases between the two vortex modes in the two spin states, respectively. b is the pulse sequence. τR and τRF are the periods of the Raman and RF pulses, respectively. T is the evolution time. c An exemplary interferometer between two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\). The Raman pulse contains two optical fields with OAM numbers L1 =−2 and L2 = 0. After BS1, there is a vortex state \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) (\(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\)) in the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\) (\(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\)). After BS2, vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\) interfere in each spin state.

Figure 1 b depicts the pulse sequence, which is interpreted as a Ramsey interferometer. The Raman and RF pulses, as the two BSs, are separated with an evolution time T. ϕ↑ as well as ϕ↓ can be adjusted during the evolution process. While in this paper, the main purpose is to prepare a lossless interferometer and demonstrate the out-of-phase relation, we set a zero evolution time T = 0. The period as well as the power of the Raman and RF pulses is selected to obtain a high interference visibility (see Methods).

Figure 1 c shows an exemplary interferometer between two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\). The Raman pulse contains two optical fields with OAM numbers L1 =−2 and L2 = 0, and l2 = l1 + (L1 − L2) =−2. The vortex states in the two spin states are imaged in three steps of the interferometer, at the input, between the two BSs, and after BS2. The spin-resolved atomic images are taken with the help of a Stern-Gerlach magnetic field and a time of flight (TOF) of 20 ms. The petal-like interferences between \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\) are clearly present in the two output spin states.

Suppose that the two-photon Raman and RF induced transitions are lossless, i.e., atoms only populate the two spin states, then the two BSs can be written as the unitary operators in quantum mechanics23,24,26, respectively,

where \({\alpha }_{\rm{R}}=\frac{1}{2}{{{\Omega}}}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}{T}_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) with the Rabi frequency \(\Omega_{\rm{R}}\) and pulse period TR of the optical Raman lights, \({\alpha }_{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}=\frac{1}{2}{{{\Omega }}}_{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}{T}_{{{{\rm{RF}}}}}\) with the Rabi frequency ΩRF and pulse period TRF of the RF field. ΔϕR and ΔϕRF are the obtained phases during the Raman and RF-induced transitions, respectively. UR transfers the OAM as well as the atomic population between the two spin states, while URF only transfers the atomic population. As seen in Fig. 1, the input state is \({(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle ,\left|\uparrow \right\rangle )}^{T}={({u}_{10}\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle ,0)}^{T}\) where u10 is the spatial wave function of the initial state. Using Eqs. (1) and (2), we can obtain the output state of the interferometer,

where Δϕ = ΔϕR − ΔϕRF.

ϕ↓ is the relative phase between the two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(| \left|{l}_{2}\right\rangle\) in the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\) and ϕ↑ is for the spin state \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\). We set Δϕ and ϕ↑,↓ in the range [ − π, π) for consideration. From Eq. (3)ϕ↑ = Δϕ and ϕ↓ = Δϕ + (2n + 1)π, where n = -1 or 0. Then we obtain a π-phase difference between the two spin states,

Equation (4) indicates that, although the relative phase (ϕ↑ or ϕ↓) in each spin state can fluctuate due to external coupling with optical Raman and RF pulses, the interferences in the two spin states have a constant π-phase difference.

The relative phase can be extracted by analyzing the angular interference pattern. θ↑ and θ↓ are defined as the azimuthal angles of the bright interference fringes in the two spin states (see Fig. 3), respectively. With Δl = l1 − l2, the azimuthal angle between two adjacent bright interference fringes is equal to 2π/∣Δl∣. Set \({\theta }_{\uparrow ,\downarrow }\in \left[-\pi /| {{\Delta }}l| ,\pi /| {{\Delta }}l| \right)\), then we get the relation of the interference fringes (see related calculations in Methods),

Considering ϕ↑ = − Δlθ↑, ϕ↓ = − Δlθ↓, and ϕ↑ − ϕ↓ = Δl(θ↓ − θ↑), Eq. (5) also exhibits the out-of-phase relation of Eq. (4). In our current experiments, the signs of θ↑,↓ are not fixed between measurements. Based on Eq. (5) with Δθ independent on the sign of Δl, we can concisely demonstrate the out-of-phase relation.

It is noted that, compared to the linear-momentum state, two vortex states can overlap at a zero relative velocity and interfere with a high stability. This unique character provides a convenient way to probe the interference pattern in each spin state.

Preparation of a lossless interferometer

Figure 2 a denotes the energy level diagram with interactions of Raman and RF pulses. A 87Rb condensate with an atom number N = 1.2(1) × 105 is produced in a spherical optical dipole trap12,27. Atoms initially populate the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle =\left|F=1,{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=-1\right\rangle\) with a zero OAM l1 = 0. Two laser beams copropagate across the ultracold atoms, transferring the OAM difference between the two laser beams (L1 =−2 and L2 = 0) to the condensate in the two-photon Raman induced transition and producing the vortex state \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\) in the spin state \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle =\left|F=1,{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=0\right\rangle\). In our previous work12, we have obtained the spin-orbital-angular-momentum coupling (SOAMC) with an adiabatic process in the trap. Here we apply the optical coupling during the expansion of the condensate after a time of 8 ms, enlarging the atomic cloud to increase the coupling strength. An RF pulse directly couples the two spin states.

a Energy level diagram. Two laser beams with OAM numbers L1 = − 2 and L2 = 0 couple the two spin states \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle =\left|F=1,{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle =\left|F=1,{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=-1\right\rangle\). δ is the two-photon detuning. ωq = 2π × 5.52 kHz is the quadratic Zeeman shift. An RF pulse also couples the two spin states \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\). b Interference patterns with loss or lossless BSs. Under the resonant condition (left column), δR = δRF = 0 kHz, three vortex modes interfere when atoms populate three spin states with loss BSs. Choosing an appropriate detuning (right column), δR = δRF = 10 kHz, two vortex modes interfere when atoms only populate two spin states with lossless BSs. c Atom ratio N+1/N versus the Raman detuning δR. N is the total atom number and N+1 is the atom number in the spin state \(\left|{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=1\right\rangle\). The insets show exemplary atomic images with δR = 0, 4, 8 kHz. d Atom ratio N+1/N versus the RF detuning δRF. δR = 10 kHz. The insets show exemplary atomic images with δRF = 7, 9, 11 kHz. The solid curve is the theoretical calculation on three-level atoms coupled with a Raman or RF pulse. The error bar is the stand deviation of several measurements.

Figure 2 b shows the interference patterns after BS2 with loss or lossless BSs. δR and δRF are the two-photon detuning of the Raman field and detuning of RF field, respectively. For the loss BSs with atoms populating three spin states, three vortex modes with l = 0, −2, −4 interfere in each spin state. The interference pattern is too complicated to experimentally determine the azimuthal angle of the interference fringe, and quantitatively obtaining the relative phase between vortex states is painful. Also theoretical analysis of the interference is difficult, where the unitary operator is invalid. For the lossless BSs with atoms only populating two spin states, two vortex modes with l = 0, − 2 interfere. The interference pattern is simple and clear in each spin state, which is convenient to extract the relative phase between vortex states. So building up a lossless interferometer is important for demonstrating the out-of-phase relation.

87Rb atom has three spin states \(\left|{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=-1,0,1\right\rangle\) in the ground state. To produce the lossless Raman and RF induced transitions in which atoms only populate the two spin states \(\left|\downarrow \right\rangle\) and \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\), a bias magnetic field introduces a large quadratic Zeeman shift ωq = 2π × 5.52kHz and a blue detuning δ is applied. This will induce a big detuning (δ + 2ωq/2π) of the spin state \(\left|{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=1\right\rangle\), resulting in a negligible population in it. In Fig. 2c, we measure the atom numbers in three spin states versus the Raman detuning δR. Here the RF pulse is absent for the population measurement. Atom ratio N+1/N decreases when increasing the blue detuning and reaches the minimum at δR ≈ 9 kHz, where N is the total atom number and N+1 is the atom number in the spin state \(\left|{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=1\right\rangle\). In the range δR ∈ (8 kHz, 12 kHz), N+1/N < 0.03. Considering that the atom number in the spin state \(\left|\uparrow \right\rangle\) also decreases with the increased detuning, we generally select a detuning at δR ∈ (8 kHz, 10 kHz). In Fig. 2d, we measure the atom ratio N+1/N versus the RF detuning δRF. N+1/N is smaller than 0.05 in the range δRF ∈ (9 kHz, 12 kHz). So we can prepare two lossless BSs by choosing detuning in the range δ ∈ (9 kHz, 10 kHz) for both pulses.

Measurement of the out-of-phase interferences

In Fig. 3, we analyze the angular interference fringe between the two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\) in the two spin states. As one exemplary measurement, the interference patterns in the two spin states are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. In the cylindrical coordinates (r, ϕ, z), \(r=\sqrt{{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}}\) is the radius and ϕ is the azimuthal angle in the x − y plane. Cold atoms are confined at z = 0. θ↑ as well as θ↓ is defined as the azimuthal angle of the bright interference fringe in each spin state. To extract θ↑,↓, we use a cosine function,

to fit the angular interference fringe, as shown in Fig. 3c and d. Δl = l1 − l2 = 2, OD is the optical density with a bias OD0, and A is the amplitude. It is noted that, to optimize the fitting, two circles with ϕ ∈ [0, 4π) are plotted. Because the azimuthal angle between the two adjacent bright interference fringes is equal to 2π/∣Δl∣, θ↑,↓ are limited in the range \(\left[-\pi /| {{\Delta }}l| ,\pi /| {{\Delta }}l| \right)\). Then we get that θ↑ = 0.7495, θ↓ = −0.7831 and Δθ = 1.5326 ≈ π/2. The black solid circle in Fig. 3a or b schematically presents the interference path. In order to accurately determine the values of θ↑,↓, we plot 15 interference fringes with a separation of 1 pixel (1 pixel ≈ 6.4 μm) along the radius r. Then θ↑,↓ as well as A are plotted versus r. We take the values of θ↑,↓ when A are the maximum. See Supplementary Note 1 for the details.

a and b Exemplary interference patterns between the two vortex states \(\left|{l}_{1}=0\right\rangle\) and \(\left|{l}_{2}=-2\right\rangle\) in the two spin states, respectively. r is the radius, ϕ is the azimuthal angle, and θ↑ as well as θ↓ is the azimuthal angle of the bight interference fringe. c and d The angular interference fringes along the paths denoted by the black solid circles in a and b, respectively. A cosine function (the red solid curve) is used to fit the interference fringe to extract θ↑,↓, i.e., θ↑ = 0.7495, θ↓ = -0.7831 and Δθ = 1.5326. e The values of θ↑ (black squares) and θ↓ (red circles) for six measurements. θ↑,↓ fluctuate shot to shot. f A constant difference between the two azimuthal angles, \({{\Delta }}\theta =\left|{\theta }_{\uparrow }-{\theta }_{\downarrow }\right|\approx \pi /2\). The insets show the corresponding interference patterns in the two spin states. The first measurement is taken as the example in a and b.

Despite the fluctuation of the azimuthal angle θ↑ (or θ↓) shot to shot in each spin state (Fig. 3e), the difference between the two azimuthal angles remains constant, i.e., Δθ = ∣θ↑ − θ↓∣ ≈ π/2 (Fig. 3f). This is the evidence of the out-of-phase interferences in the two spin states. The Raman and RF pulses will transfer their phases (ΔϕR and ΔϕRF) to the two spin states during their interactions with atoms. The fluctuations of ΔϕR and ΔϕRF shot to shot result in the variation of the relative phase Δϕ (see Eq. (3)), causing the randomness of θ↑ and θ↓. We can calculate Δϕ as well as ϕ↑,↓ from each measurement of θ↑,↓ according to the relations ϕ↑ = Δϕ = −Δlθ↑ and ϕ↓ = −Δlθ↓ (see “Methods”). For the measurements in Fig. 3a and b, ϕ↑ = Δϕ = −1.4990, ϕ↓ = 1.5662 and ϕ↓ − ϕ↑ = 3.0652 ≈ π. In Fig. 3e and f, ∣ϕ↓ − ϕ↑∣ ≈ π holds for the six measurements, which also demonstrates the out-of-phase relation. In fact, we can calculate the interference pattern with the measured value of Δϕ. The measured values of Δϕ and the calculated interference patterns for different Δl are shown in Supplementary Note 2.

In Fig. 4, we demonstrate the out-of-phase relation for different Δl. We obtain various values of Δl by choosing different configurations of the optical Raman pulse, i.e., (L1 = 1, L2 = −2) for Δl = − 3, (L1 = 0, L2 = −2) for Δl = −2, (L1 = 0, L2 = −1) for Δl = − 1, (L1 = −1, L2 = 0) for Δl = 1, (L1 = −2, L2 = 0) for Δl = 2, and (L1 = −2, L2 = 1) for Δl = 3. The winding numbers L1,2 of optical OAMs are controlled by the spatial light modulator (SLM). Δθ is measured using the same method as in Fig. 3. A collection of the measurements is shown in Fig. 4. The theoretical calculation of Eq. (5), Δθ = π/∣Δl∣, agrees well with the experimental results.

Δθ is plotted as a function of Δl. From left to the right, Δl = −3, −2, −1, 1, 2, 3. The solid curve denotes the calculation of Eq. (5). The error bar is the standard deviation of six measurements.

In Fig. 5, we demonstrate the out-of-phase relation for different constituents of the Raman pulse and during the expansion of the condensate. Eq. (5) indicates that Δθ only depends on ∣Δl∣, but not on the constituent of the Raman pulse. This is analogous to a BS whose property doesn’t depend on its composition. In Fig. 5a, ∣Δl∣ = ∣L2 − L1∣ = 2. Different constituents of the Raman pulse are applied, i.e., (L1 = −1, L2 = 1), (L1 = −2, L2 = 0), (L1 = 1, L2 = −1), and (L1 = 0, L2 = −2). Δθ remains constant, Δθ = π/2. This constant value also holds for different expansion times of the condensate, as indicated in Fig. 5b.

a Δθ for different constituents of the Raman pulse, i.e., (L1 = −1, L2 = 1), (L1 = −2, L2 = 0), (L1 = 1, L2 = −1), and (L1 = 0, L2 = −2). ∣Δl∣ = 2 and TOF = 20 ms. b Δθ for different TOFs, i.e., TOF = 19 ms, 20 ms, 21 ms, 22 ms. L1 = −2 and L2 = 0. The dashed line denotes the value of π/2. The error bar is the standard deviation of six measurements.

Discussion

In current experiments, based on the lossless matter-wave interferometer, we can measure the relative phase between two vortex states. This ability is important for accurately measuring an external field. For example, to measure a magnetic filed B, we should set a finite evolution time T ≠ 0 (see Fig. 1b) and improve the coherence between the Raman and RF pulses. During the evolution time T, atoms will evolve with a phase shift termed as \(\exp (-i{\omega }_{{{{\rm{Larmor}}}}}T)\) between two spin states, where ωLarmor is the Larmor frequency under an external magnetic field. The accumulated phase shift due to the Larmor procession will evolve into the relative phase between vortex states (ϕ↑ or ϕ↓) after BS2 and can be measured from the azimuthal angle (θ↑ or θ↓). The measurement precision of the magnetic field depends on both the uncertainty of the azimuthal angle δθ and evolution time T, \(\delta B=\frac{\hslash \bigtriangleup l\delta \theta }{T{g}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}{\mu }_{\rm{B}}{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}}\), where ћ is the reduced Planck constant, gF is the hyperfine Lande g-factor, μB is the Bohr magneton and mF is the magnetic quantum number. With a preliminary value δθ = 0.032 rad and assuming an evolution time T = 10 ms, the sensitivity for a single measurement is δB ≈ 146 pT, which is at the same level as those obtained in references28,29. In previous works28,30, the Ramsey interferometer is composed of two RF pulses, and people probe the spin polarization of multiple spin components to measure the magnetic field. In our proposal, the lossless Ramsey interferometer is composed of an optical Raman pulse and an RF pulse, and one can probe the spatial interference fringes of two vortex states to measure the magnetic field. So there exist two advantages: (1) one can measure a large magnetic field, (2) the measurement precision is insensitive to the fluctuation of the atomic number. Certainly heating effects due to the finite temperature (condensate purity) or atomic interaction will cause atomic loss and dephasing, which will decrease the measurement sensitivity to some extent.

In conclusion, we report the experimental realization of a vortex matter-wave interferometer in ultracold quantum gases. We show the ability to quantitatively measure the relative phase between two vortex states by analyzing the angular interference fringe. By producing a lossless interferometer, we demonstrate the out-of-phase relation for the interferences in the two spin states. We further prove the robustness of this out-of-phase relation, not sensitive to the angular-momentum difference between the two interfering vortex states, constituent of Raman optical fields and expansion of the condensate. This work makes an important step forward to accurately measure an external field using a vortex matter-wave interferometer.

Methods

Experimental setup

We produce a spherical Rb condensate using the combination of the optical force and gravity as shown in references12,27. The trapping frequency is ω = 2π × 77.5 Hz. The OAM number is a good quantum number in a system with rotational symmetry. The atom number is N = 1.2(1) × 105 and the temperature is T ≈ 50 nK. The cold atoms initially populate the spin state \(\left|\downarrow \right. \rangle =\left|F=1,{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}=-1\right. \rangle\) with a zero OAM l1 = 0. Two laser beams with different OAMs (L1 and L2) copropagate across the ultracold atoms, transferring the OAM difference of two laser beams (ΔL = L1 − L2) to the condensate in the two-photon Raman induced transition, while suppressing the transfer of the linear momentum. A pair of Helmholtz coils produce a bias magnetic field B0, which provides the quantum axis and a large quadratic Zeeman shift ωq = 2π × 5.52 kHz of the Rb ground spin states. A pair of anti-Helmholtz coils produce a pulse of a gradient magnetic field ∂B/∂r to spatially separate different spin states. The probe beam counterpropagates with the Raman beams, detecting the density distribution of the condensate in the plane r − ϕ.

After a TOF of 8 ms, the condensate is coupled by a pair of Raman lights (L1 and L2) followed with an RF pulse. The atom size is about 10 μm. For the Raman laser beam, the waist is about 70 μm, the power is about 30 mW. We use the tune-out wavelength λ = 790.02 nm of the two Raman beams, in which the ground spin manifold of the Rb atom experiences no scalar ac Stark shift. This can ensure that any vortex structure observed in the condensate is produced due to the OAM transferring, not the trapping effect of the vortex laser beam. The period of the Raman as well as RF pulse is 60 μs. The Rabi frequency of the optical Raman fields is spatially dependent. The Rabi frequency of the RF field is 2π × 1.67 kHz, which is determined by measuring the Rabi oscillation of the atom numbers in the two spin states. The period as well as the power of the Raman and RF pulses are selected to obtain a high interference visibility. A gradient magnetic field (∂B/∂r) is applied to spatially separate different spin states. The spin-resolved density is probed with a TOF of 20 ms.

Magnetic field calibration

The absolute value and stability of the detuning δ is mainly determined by the bias magnetic field B0. We calibrate the magnetic field by adiabatically coupling the ground spin states of F = 1 with an RF passage. We scan the RF signal from 6.090 MHz to different values in 50 ms and simultaneously record the populations of the three spin states. The Hamitonian of the system dressed by the RF signal is

where δRF/h = νRF − ν0 is the RF detuning. \(h{\nu }_{0}=({E}_{{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} = -1}-{E}_{{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} = 1})/2\) is the effective resonant position, which is set by the bias magnetic field B0. ΩRF is the coupling strength of the RF signal. \(\epsilon ={E}_{{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} = 0}-({E}_{{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} = -1}+{E}_{{m}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} = 1})/2\) is the quadratic Zeeman shift. Then we can numerically calculate the relative populations of the three spin states. From the comparison between the experimental measurements and the numerical calculations, we can deduce the bias magnetic field B0 = 8.807 G. By repeating the measurements many times and observing the fluctuation of the resonance position, we can determine the magnetic field stability ΔB ≈ 1 mG.

Calculation of the out-of-phase relation

Here we deduce the out-of-phase relation of Eq. (5). The vortex state is written as \(\left|l\right. \rangle ={e}^{-il\theta }\). From Eq. (3), the density distributions of the two spin states \(\left|\downarrow \right. \rangle\) and \(\left|\uparrow \right. \rangle\) can be written as

where Δl = l1 − l2. Then the bright interference fringes in the two spin states are written as

where m as well as p is an integer number. Set \({\theta }_{\downarrow ,\uparrow }\in \left[-\pi /|{{\Delta }}l|,\pi/ |{{\Delta }}l|\right)\) and \(\Delta\,\phi\in \left[-\pi,\pi\right)\). Then p = 0 and m = −1 or 0. We get the relations,

Then we can obtain Eq. (5) by taking modules on both sides of Eq. (10). From Eq. (11) we can calculate the relative phase Δϕ from the measurement of θ↑.

ϕ↑ and ϕ↓ are the interference phases in spin states \(\left|\uparrow \right. \rangle\) and \(\left|\downarrow \right. \rangle\), respectively. Set \({\phi}_{\downarrow,\uparrow}\in \left[-\pi,\pi\right)\). From Eq. (3), ϕ↑ = Δϕ and ϕ↓ = Δϕ + (2n + 1)π, where n = −1 or 0. In the condition of Eq. (9), ϕ↑ = −Δlθ↑ and ϕ↓ = −Δlθ↓. Then we get the relation,

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

The codes used for simulation and analysis will be made available to the interested reader upon reasonable request.

References

Cronin, A. D., Schmiedmayer, J. & Pritchard, D. E. Optics and interferometry with atoms and molecules. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1051–1129 (2009).

Andrews, M. R. et al. Observation of interference between two Bose condensates. Science 275, 637–641 (1997).

Schumm, T. et al. Matter-wave interferometry in a double well on an atom chip. Nat. Phys. 1, 57–62 (2005).

Simsarian, J. E. et al. Imaging the phase of an evolving Bose-Einstein condensate wave function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2040–2043 (2000).

Gross, C., Zibold, T., Nicklas, E., Esteve, J. & Oberthaler, M. K. Nonlinear atom interferometer surpasses classical precision limit. Nature 464, 1165–1169 (2010).

Machluf, S., Japha, Y. & Folman, R. Coherent Stern-Gerlach momentum splitting on an atom chip. Nat. Commun. 4, 2424 (2013).

Margalit, Y. et al. A self-interfering clock as a “which path” witness. Science 349, 1205–1208 (2015).

Allen, L., Beijersbergen, M. W., Spreeuw, R. J. C. & Woerdman, J. P. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 45, 8185–8189 (1992).

Allen, L., Barnett, S. M. & Padgett, M. J. Optical Angular Momentum (Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol, 2003).

Shen, Y. et al. Optical vortices 30 years on: OAM manipulation from topological charge to multiple singularities. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 90 (2019).

Wright, K. C., Leslie, L. S., Hansen, A. & Bigelow, N. P. Sculpting the vortex state of a spinor BEC. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 030405 (2009).

Zhang, D. et al. Ground-state phase diagram of a spin-orbital-angular-momentum coupled Bose-Einstein condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 110402 (2019).

Chen, H.-R. et al. Spin–orbital-angular-momentum coupled Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 113204 (2018).

Chen, P.-K. et al. Rotating atomic quantum gases with light-induced azimuthal gauge potentials and the observation of the Hess-Fairbank effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 250401 (2018).

Pelegrí, G., Mompart, J. & Ahufinger, V. Quantum sensing using imbalanced counter-rotating Bose Einstein condensate modes. New J. Phys. 20, 103001 (2018).

Thanvanthri, S., Kapale, K. T. & Dowling, J. P. Ultra-stable matter-wave gyroscopy with counter-rotating vortex superpositions in Bose-Einstein condensates. J. Mod. Opt. 59, 1180–1185 (2012).

Moxley, F. I., Dowling, J. P., Dai, W. & Byrnes, T. Sagnac interferometry with coherent vortex superposition states in exciton-polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. A 93, 053603 (2016).

Kiałka, F., Stickler, B. A. & Hornberger, K. Orbital angular momentum interference of trapped matter waves. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 022030 (2020).

Haine, S. A. Mean-field dynamics and Fisher information in matter wave interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 230404 (2016).

Nolan, S. P., Sabbatini, J., Bromley, M. W. J., Davis, M. J. & Haine, S. A. Quantum enhanced measurement of rotations with a spin-1 Bose-Einstein condensate in a ring trap. Phys. Rev. A 93, 023616 (2016).

Mair, A., Vaziri, A., Weihs, G. & Zeilinger, A. Entanglement of the orbital angular momentum states of photons. Nature 412, 313–316 (2001).

Babazadeh, A. et al. High-dimensional single-photon quantum gates: concepts and experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180510 (2017).

Kapale, K. T. & Dowling, J. P. Vortex phase qubit: generating arbitrary, counterrotating, coherent superpositions in Bose-Einstein condensates via optical angular momentum beams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 173601 (2005).

Thanvanthri, S., Kapale, K. T. & Dowling, J. P. Arbitrary coherent superpositions of quantized vortices in Bose-Einstein condensates via orbital angular momentum of light. Phys. Rev. A 77, 053825 (2008).

Andersen, M. F. et al. Quantized rotation of atoms from photons with orbital angular momentum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 170406 (2006).

Zeilinger, A. General properties of lossless beam splitters in interferometry. Am. J. Phys. 49, 882–883 (1981).

Li, R. et al. Expansion dynamics of a spherical Bose-Einstein condensate. Chin. Phys. B 28, 106701 (2019).

Eto, Y. et al. Spin-echo-based magnetometry with spinor Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 88, 031602 (2013).

Muessel, W., Strobel, H., Linnemann, D., Hume, D. B. & Oberthaler, M. K. Scalable spin squeezing for quantum-enhanced magnetometry with Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 103004 (2014).

Gosar, K. et al. Single-shot Stern-Gerlach magnetic gradiometer with an expanding cloud of cold cesium atoms. Phys. Rev. A 103, 022611 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Han Pu for valuable discussions and comments on our manuscript. This work has been supported by the NKRDP (National Key Research and Development Program) under Grant No. 2016YFA0301503, NSFC (Grant Nos. 11674358, 11904388, 12004398, 12121004, 11974384), CAS under Grant No. YJKYYQ20170025, K. C. Wong Education Foundation (Grant No. GJTD-2019-15), and Hubei province under Grant No. 2021CFA027.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J. and T.G. designed the experiment; L.K., T.G., and L.N. did the experiment; L.K., T.G., L.N., and K.J. analyzed the experimental data; L.K., and K.J. performed the theoretical calculation; L.K., T.G., and K.J. wrote the paper; All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the manuscript; K.J. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Gao, T., Nie, L. et al. Phase-locking matter-wave interferometer of vortex states. npj Quantum Inf 8, 78 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00585-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00585-5