Abstract

In a chiral one-dimensional atom, a photon propagating in one direction interacts with the atom; a photon propagating in the other direction does not. Chiral quantum optics has applications in creating nanoscopic single-photon routers, circulators, phase-shifters, and two-photon gates. Here, we implement chiral quantum optics using a low-noise quantum dot in an open microcavity. We demonstrate the non-reciprocal absorption of single photons, a single-photon diode. The non-reciprocity, the ratio of the transmission in the forward-direction to the transmission in the reverse direction, is as high as 10.7 dB. This is achieved by tuning the photon-emitter coupling in situ to the optimal operating condition (β = 0.5). Proof that the non-reciprocity arises from a single quantum emitter lies in the photon statistics—ultralow-power laser light propagating in the diode’s reverse direction results in a highly bunched output (g(2)(0) = 101), showing that the single-photon component is largely removed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

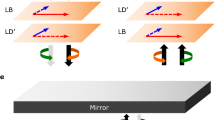

In a non-chiral one-dimensional atom, an atom is coupled equally to a right-propagating and to a left-propagating mode in a single-mode waveguide. There are two input/output ports, one on the left (port 1) and one on the right (port 2). In the ideal limit (perfect atom with β = 1, where β is the probability that the excited atom emits a photon into the waveguide mode, a single photon at the input in resonance with the atom), the atom acts as a perfect mirror: the reflectivity is R = 1; the transmission T = 01,2. This changes completely in a chiral one-dimensional atom: R and T depend on the propagation direction, left-to-right (1 → 2) or right-to-left (2 → 1), i.e., the system exhibits non-reciprocity (T1→2 ≠ T2→1). There are two simple cases3. First, for β = 1, the atom now becomes perfectly transparent (T1→2 = 1, T2→1 = 1, R1→1 = 0, R2→2 = 0). In one direction, the 2 → 1-direction, say, the photon is phase-shifted by π via the interaction with the atom; in the other direction, 1 → 2, the photon phase-shift is zero. Second, for \(\beta =\frac{1}{2}\): in the 2 → 1-direction, the photon is scattered by the atom into non-waveguide modes—the photon is absorbed—such that T2→1 = 0 and R2→2 = 0, whereas in the 1 → 2-direction, the photon does not interact with the atom, T1→2 = 1 and R1→1 = 0.

Chiral quantum optics has been implemented by using a single emitter in a nano-engineered waveguide, for instance a Rb atom in the evanescent field of a dielectric nanofibre4,5, or a semiconductor quantum dot in a waveguide6,7,8. In the semiconductor case, β-factors can be high in nano-beam structures and particularly high in photonic-crystal waveguides. The system becomes chiral provided the quantum dot is located off-centre in a nano-beam8, and at the centre of an inversion-asymmetric photonic-crystal waveguide6.

We report here a different approach to engineering a chiral one-dimensional atom. A single-mode optical fibre constitutes the waveguide on the ‘left’ of the quantum dot; another single-mode optical fibre constitutes the waveguide on the ‘right’ of the quantum dot; the atom itself is a quantum dot in a low-volume one-sided microcavity, where the microcavity is coupled with high efficiency to the single-mode fibres. Chirality is induced by applying a magnetic field to a neutral quantum dot: the quantum dot’s σ+-transition couples to the microcavity and is addressed with σ+-polarised photons. The advantage of this approach is that the resonant microcavity boosts the light-matter interaction in a controllable way: the β-factor can be tuned from small to extremely high values (99.7% has been achieved9). Also, the good mode-matching10 implies that a high-efficiency, fibre-coupled platform for chiral quantum optics can be constructed.

Here, we implement the chiral scheme with \(\beta =\frac{1}{2}\). In one direction, a single photon is transmitted; in the other direction, the photon is absorbed, Fig. 1a. We call this device a ‘single-photon diode’ in analogy to its electronic counterpart. The challenge is twofold: to achieve exactly the right β, and to achieve a close-to-perfect (transform-limited) quantum dot. These challenges were met: we achieve an isolation of 10.7 dB, the highest non-reciprocal response recorded with a single quantum emitter. In addition, the high overall efficiency10 enables us to observe optical nonlinearities already at an input power of just 100 pW. The quantum nature of this nonlinearity is validated by observation of photon bunching by a factor of 101 compared to that of a laser field.

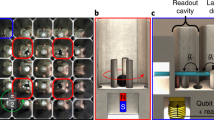

a The optical system showing the two input/output ports. b Illustration of the open microcavity. The heterostructure consists of a GaAs/AlAs distributed Bragg reflector (the ‘bottom’ mirror) and self-assembled InAs quantum dots embedded in an n-i-p diode. Nano-positioners allow precise tuning of both microcavity frequency (via Z) and also the β-factor by positioning the quantum dots with respect to the anti-node of the microcavity (via XY). An external magnetic field of 2.0 T splits the neutral quantum dot into two circularly-polarised transitions. The polarisation of the light is controlled by a polarising beam-splitter (PBS) and a quarter-wave plate (λ/4) in the microscope. The σ+-polarised exciton creates a photon in the microcavity with probability β. c Transmission from port 1 to port 2 versus quantum dot detuning for three different lateral positions of the quantum dot: orange triangles (β ≈ 0.72), purple circles (β ≈ 0.50), and blue rectangles (β ≈ 0.12). The solid lines are theory curves. The off-resonant transmission is limited to 0.7 by the residual non-degeneracy of the microcavity. The transmission is defined without taking into account the losses in the optical setup. The overall end-to-end throughput of the setup, taking into account all the optical elements and the fibre-coupling, is 56%: this corresponds to T = 1. d Contrast in the transmission as a function of the lateral position. Coloured data-points indicate the positions used in (b). The black solid line is the theory.

Results

The working principle of the single-photon diode

Figure 1b shows a schematic of the setup and the operation principle of the diode. The optical setup consists of a polarising beam-splitter and a quarter-wave plate set at 45∘ with respect to the polarising beam-splitter axes. Consequently, light propagating in the forward direction is mapped to a left-handed field at the input of the microcavity, while light propagating in the backward direction is mapped to a right-handed field at the microcavity input, thereby creating the spin-momentum locking. The microcavity (Fig. 1b) comprises a highly reflective ‘bottom’ mirror and a much less reflective ‘top’ mirror10. The top mirror is a dielectric distributed-Bragg-reflector deposited on a crater in a silica substrate with a radius-of-curvature of 11 μm. The bottom mirror is a semiconductor distributed-Bragg-reflector on top of which InAs quantum dots are embedded in an n-i-p diode in the heterostructure. The open nature of the microcavity allows the lateral position of the quantum dots to be controlled precisely with respect to the anti-node of the microcavity. This allows in situ tuning of the β-factor. Furthermore, adjusting the distance between the bottom mirror and the top mirror provides precise control over the microcavity’s frequency, enabling the quantum dot’s σ+-polarised exciton and the microcavity to be brought into spectral resonance.

We define the transmission as the propagation through the entire diode, i.e., from port 1 to 2 (2 to 1) in the forward (backward) direction. Ideally, the transmission in the forward direction T1→2 is unity as the left-handed optical field is orthogonal to the dipole-moment of the quantum dot, i.e., there is no interaction. In the backward direction, the transmission amplitude is given by t2→1 = 1 − 2β where β is the β-factor describing the interaction of the σ+-polarised exciton with an empty microcavity. The full transmission in the backward direction is \({T}_{2\to 1}={\left|{t}_{2\to 1}\right|}^{2}={\left|1-2\beta \right|}^{2}\). In the over-coupled regime, β ≈ 1, the backwards-propagating photons receive a π-phase shift as they transit through the coupled system. At the critical coupling, β = 0.5, the light reflected by the quantum dot should interfere destructively with the light directly reflected from the microcavity and the transmission through the system vanishes; instead, the photons are scattered into non-microcavity modes.

For this scheme to operate, the microcavity itself should not rotate the polarisation. However, the fundamental microcavity mode is typically split into two modes with orthogonal linear polarisations, a consequence of a birefringence in the semiconductor heterostructure11. This mode-splitting decreases with increasing wavelength while the microcavity linewidth, κ/(2π), increases (Supplementary Note 2). We operate at a wavelength of 945 nm where the mode-splitting is on the order of 29 GHz and κ/(2π) = 102 GHz such that the mode-splitting is much smaller than the linewidth of the microcavity, and the microcavity mode is nearly degenerate. The microcavity losses are dominated by the transmission through the top mirror, i.e., κtop ≫ κbottom (Supplementary Note 2). Note that in this regime, the residual mode-splitting acts as an overall loss channel and does not limit the non-reciprocity of the system; it mostly affects the insertion loss of the system (here 1.5 dB).

The inset in Fig. 1b shows the level structure of a neutral quantum dot under a magnetic field along the growth direction (Faraday geometry). An out-of-plane magnetic field of 2.0 T splits the right-handed and left-handed transitions by 63 GHz, enough that only one transition interacts with the laser; here, the right-handed dipole σ+ (see Supplementary Note 2 for characterisation of the quantum dot). The microcavity system resides in a cryostat at a temperature of 4.2 K.

Tuning the β-factor to the ideal limit

The transmission of the diode is probed with coherent laser light at very low powers, a regime dominated by single-photon components. We exploit the β-factor’s dependence on the lateral position of the quantum dot with respect to the centre of the microcavity to tune the system to the critical-coupling condition. Figure 1c shows the transmission in the backward direction, T2→1, as a function of the quantum dot frequency for three different positions, i.e., three different β-factors. The orange data points show the transmission for the quantum dot centred in the microcavity. For this position, we extract β = 0.72, matching well the theoretical expectations for the maximum achievable β at this wavelength (Supplementary Note 3). The β-factor is evaluated via the linewidth and the contrast of the dip. When the quantum dot is laterally displaced such that β = 0.50 (purple data points), the T2→1 is lowest: T2→1 = 0.07. Also, the linewidth of the quantum dot transition decreases with decreasing β due to a reduced Purcell-enhancement. We define the transmission contrast as one minus the ratio between transmission on resonance and the transmission far off-resonance with the quantum dot (\(1-\frac{{T}_{2\to 1}^{0}}{{T}_{2\to 1}^{\infty }}\)). The transmission contrast is measured while scanning the lateral position of the quantum dot relative to the microcavity’s optical axis (Fig. 1d). For a well-centred position, the contrast in the transmission is around 0.67, increasing to a value of 0.9 as β approaches 0.5, and decreasing as β is further reduced. The solid black lines in Fig. 1c, d are the theoretically expected behaviour. (A comprehensive model for transmission through a two-level system coupled to a non-degenerate one-sided microcavity is derived and discussed in detail in Supplementary Note 1.) An average spectral fluctuation of the quantum dot of 40 MHz was found by comparing the theoretical model and the measurements12.

Non-reciprocal transmission of the single-photon diode

For the operation of the single-photon diode, we focus at the position with the largest transmission contrast, β = 0.50. The non-reciprocal nature of the diode is demonstrated by measuring the transmission in both directions at the critical-coupling condition. Figure 2a shows the transmission through the diode in the backward direction as a function of the microcavity detuning and the quantum dot detuning. The transmission contrast shown in these maps decreases with microcavity detuning on account of a reduced β-factor. On the contrary, the transmission in the forward direction (Fig. 2b) presents an almost flat behaviour independent of the detuning from the quantum dot’s resonance. The panels on the right side of Fig. 2a, b shows the theoretically predicted behaviour from our model (Supplementary Note 1). A comparison of the transmission in the forward and backward directions as a function of the quantum dot (microcavity) detuning is shown in Fig. 2c, d. At resonance, the transmission in the forward direction is around 0.82. The slight increase in the transmission signal in the forward direction is attributed to the mode-splitting based on the theoretical model (see Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). A figure of merit for a diode is the isolation. It is defined as T1→2/T2→1 and found to be a factor 11.9 (corresponding to 10.7 dB).

Transmission through the system versus quantum dot and microcavity detuning for the backward (a) (port 1 to 2) and forward (b) (port 2 to 1) directions. Experimental data (left) and theory (right) show an excellent match. The black lines show the Lamb shift of the quantum dot resonance induced by the vacuum field of the microcavity. c, d Transmission through the diode on resonance with the microcavity/quantum dot in the forward and the backward direction versus quantum dot/cavity detuning. The purple and turquoise data are cut-throughs of a (2 → 1) and b (1 → 2). The black solid lines are the theory.

Nonlinearity of the single-photon diode

To prove that the non-reciprocity arises from a single emitter, we probe both the power dependence and the photon statistics of the output. In the power dependence, we find a striking nonlinearity of the transmission in the backward direction. Figure 3a shows the transmission in the backward direction as a function of the optical power and detuning from the quantum dot’s resonance. On resonance with the quantum dot (Fig. 3b), the backward transmission increases with a power-law dependence with a slope of one and is described by \({T}_{2\to 1}^{0}=\frac{P/{P}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}}{1+P/{P}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}}\), where P is the input optical power and PC the critical power. The experimental data in Fig. 3b match this behaviour very well for PC = 213 pW. This behaviour is characteristic of the saturation of a two-level system—while the interaction between the input field and the quantum dot is linear in power at very low powers, the quantum dot saturates at higher input powers, which leads to a strong power-dependent transmission. The critical power is very close to the theoretically expected value of 198 pW (Eq. (9) in Supplementary Note 1). This power level corresponds to an average photon flux of \(\left\langle n\right\rangle =0.27\) at the input of the microcavity per lifetime of the quantum dot (τQD = 0.26 ns).

a Transmission on resonance with the microcavity versus quantum dot detuning and optical input power. The transmission saturates at 0.7 on increasing the power. b Power dependence of the transmission on resonance with the quantum dot. The black solid line corresponds to the theory. The insets illustrate absorption by the quantum dot at small powers, and transmission at higher powers due to the increasing transparency of the emitter. The critical power is indicated with a vertical line. c Autocorrelation function of the backwards propagating light for three different input optical powers. At the lowest optical power (5 pW) a bunching of 101 is observed. As the power increases the bunching decreases.

The very low onset of the nonlinearity implies that the quantum statistics of the output field are affected by interaction with the quantum dot13. We verify this by measuring the second-order auto-correlation function, g(2)(τ), of the backward transmitted light14,15,16,17. The g(2)(τ) was measured for three different powers (Fig. 3c). At the lowest power (5 pW), a very strong bunching of 101 is observed, proving that the single-photon components of the laser have been largely removed by the quantum dot. With increasing power, the bunching decreases rapidly and eventually vanishes, corresponding exactly to the expected behaviour on saturating the quantum dot: at high powers, most of the laser light is transmitted without interaction, resulting in g(2)(τ) = 1, the auto-correlation function of the laser light. Additionally, the auto-correlation function of the transmission in the forward direction is constant and unitary—this confirms the non-reciprocal transmission in the system (see Supplementary Note 4). The measurements were modelled (see Supplementary Note 4) and the results are depicted as a solid black line in Fig. 3c. We emphasise that all the data in Figs. 2 and 3 are modelled with the same set of parameters, in particular β = 0.50 and a free-space decay rate γ0/(2π) = 300 MHz.

Discussion

The reported experiments reveal a strong non-reciprocal and highly nonlinear transport of optical photons through a quantum dot-microcavity system. Model calculations based on the canonical chiral one-dimensional atom describe the system extremely well. The single-photon diode is realised with a modest emitter-microcavity coupling, β = 0.5. We can foresee a range of applications. For example, the non-reciprocal behaviour can be dynamically controlled by driving the σ− transition, by using the spin-state of a charge carrier in the quantum dot, or by fast Stark tuning of the quantum dot, opening possibilities for optical switches and transistors18,19,20,21,22. Theory predicts that the strong bunching of the photons in the transmission of the system presages the formation of a two-photon bound state—it is a first step in creating exotic photonic states and simulating many-body dynamics using photons23,24,25,26. The performance of the system can be further improved by eliminating the mode-splitting of the microcavity. The mode-splitting can be minimised, perhaps eliminated, by exploiting the electro-optic effect27 or by applying uni-axial stress to the semiconductor heterostructure11. This would not only reduce the insertion losses but also bring the regime β = 1 within range. Such a device would be ideal for achieving a single-photon phase-shifter and has a strong potential for deterministic two-photon quantum gates, either by using spin-state of the quantum dot or by exploiting photonic bound states28,29.

Methods

Experimental Setup

The microcavity consists of a flat distributed Bragg reflector with 46 pairs of GaAs/AlAs layers and a curved top mirror (radius of curvature of 12 μm) coated with 8 pairs of Ta2O5/SiO2, see ref. 10 for more details about the cavity. The microcavity is placed on a set of nano-positioners (ANP101/ANP51, attocube systems AG). A lens (355230-B, NA = 0.55, Thorlabs Inc.) focuses the light on the microcavity input. The microcavity and the lens are mounted in a helium bath-cryostat (4.2 K). A DLC CTL 959 laser (TOPTICA Photonics AG) is used for all experiments. All transmission measurements were performed using a fibre-coupled silicon avalanche photodetector (APD, model SPCM-NIR, Excelitas Technologies) with a detection efficiency of ηAPD = (44 ± 3)%. The g(2)(τ)-measurements were performed with a superconducting NbTiN-nanowire single-photon detector (SNSPD) unit (EOS 210 CS, Single Quantum B.V.) that has an efficiency of ηSNSPD = (82 ± 5)%. The signals from the SNSPDs were analysed using a time tagger (Time Tagger Ultra, Swabian Instruments GmbH) with a jitter of 9 ps.

Data availability

The data that supports this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that has been used for this work is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Auffèves-Garnier, A., Simon, C., Gérard, J.-M. & Poizat, J.-P. Giant optical nonlinearity induced by a single two-level system interacting with a cavity in the Purcell regime. Phys. Rev. A 75, 053823 (2007).

Shen, J.-T. & Fan, S. Theory of single-photon transport in a single-mode waveguide. I. Coupling to a cavity containing a two-level atom. Phys. Rev. A 79, 023837 (2009).

Lodahl, P. et al. Chiral quantum optics. Nature 541, 473–480 (2017).

Sayrin, C. et al. Nanophotonic optical isolator controlled by the internal state of cold atoms. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041036 (2015).

Scheucher, M., Hilico, A., Will, E., Volz, J. & Rauschenbeutel, A. Quantum optical circulator controlled by a single chirally coupled atom. Science 354, 1577–1580 (2016).

Söllner, I. et al. Deterministic photon-emitter coupling in chiral photonic circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 775–778 (2015).

Coles, R. J. et al. Chirality of nanophotonic waveguide with embedded quantum emitter for unidirectional spin transfer. Nat. Commun. 7, 11183 (2016).

Hurst, D. L. et al. Nonreciprocal transmission and reflection of a chirally coupled quantum dot. Nano Lett. 18, 5475–5481 (2018).

Najer, D. et al. A gated quantum dot strongly coupled to an optical microcavity. Nature 575, 622–627 (2019).

Tomm, N. et al. A bright and fast source of coherent single photons. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 399–403 (2021).

Tomm, N. et al. Tuning the mode splitting of a semiconductor microcavity with uniaxial stress. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 054061 (2021).

Kuhlmann, A. V. et al. Charge noise and spin noise in a semiconductor quantum device. Nat. Phys. 9, 570–575 (2013).

Rice, P. R. & Carmichael, H. J. Single-atom cavity-enhanced absorption. I. Photon statistics in the bad-cavity limit. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 24, 1351–1366 (1988).

Wang, D. et al. Turning a molecule into a coherent two-level quantum system. Nat. Phys. 15, 483–489 (2019).

Pscherer, A. et al. Single-molecule vacuum Rabi splitting: Four-wave mixing and optical switching at the single-photon level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 133603 (2021).

Tiecke, T. G. et al. Nanophotonic quantum phase switch with a single atom. Nature 508, 241–244 (2014).

Snijders, H. et al. Purification of a single-photon nonlinearity. Nat Commun. 7, 12578 (2016).

Chang, D. E., Sørensen, A. S., Demler, E. A. & Lukin, M. D. A single-photon transistor using nanoscale surface plasmons. Nat. Phys. 3, 807–812 (2007).

Witthaut, D., Lukin, M. D. & Sørensen, A. S. Photon sorters and QND detectors using single photon emitters. EPL 97, 50007 (2012).

Javadi, A. et al. Spin-photon interface and spin-controlled photon switching in a nanobeam waveguide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 398–403 (2018).

Shomroni, I. et al. All-optical routing of single photons by a one-atom switch controlled by a single photon. Science 345, 903–906 (2014).

O’Shea, D., Junge, C., Volz, J. & Rauschenbeutel, A. Fiber-optical switch controlled by a single atom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 193601 (2013).

Noh, C. & Angelakis, D. G. Quantum simulations and many-body physics with light. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 016401 (2016).

Hafezi, M., Lukin, M. D. & Taylor, J. M. Non-equilibrium fractional quantum Hall state of light. New J. Phys. 15, 063001 (2013).

Gullans, M. et al. Efimov states of strongly interacting photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 233601 (2017).

Maghrebi, M. et al. Coulomb bound states of strongly interacting photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 123601 (2015).

Frey, J. A. et al. Electro-optic polarization tuning of microcavities with a single quantum dot. Opt. Lett. 43, 4280–4283 (2018).

Ralph, T., Söllner, I., Mahmoodian, S., White, A. & Lodahl, P. Photon sorting, efficient bell measurements, and a deterministic controlled-Z gate using a passive two-level nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 173603 (2015).

Mahmoodian, S., Calajó, G., Chang, D. E., Hammerer, K. & Sørensen, A. S. Dynamics of many-body photon bound states in chiral waveguide QED. Phys. Rev. X 10, 031011 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sahand Mahmoodian and Daniel Najer for stimulating discussions. The work was supported by NCCR QSIT and SNF Projects Nos. 200020_175748 and 200020_204069. A.J. received funding from the European Unions Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 840453 (HiFig). T.J. acknowledges support from the European Unions Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 792853 (Hi-FrED). R.S., A.D.W., and A.L. acknowledge financial support from the grants DFH/UFA CDFA05-06, DFG TRR160, DFG project 383065199, and BMBF QR.X 16KISQ009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.O.A. carried out the experiments with help from N.T. and A.J. R.S., A.D.W., and A.L. designed and grew the semiconductor heterostructure. N.T. fabricated the top mirror, passivated the sample, and assembled the cavity setup. N.T. and T.J. characterised the top mirror. NOA developed the theoretical model and analysed the data. A.J. and R.J.W. conceived the idea and supervised the project. N.O.A., A.J., and R.J.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antoniadis, N.O., Tomm, N., Jakubczyk, T. et al. A chiral one-dimensional atom using a quantum dot in an open microcavity. npj Quantum Inf 8, 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00545-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-022-00545-z