Abstract

Electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots have been intensively studied for implementing quantum computation and high-fidelity single- and two-qubit operations have recently been achieved. Quantum teleportation is a three-qubit protocol exploiting quantum entanglement and it serves as an essential primitive for more sophisticated quantum algorithms. Here we demonstrate a scheme for quantum teleportation based on direct Bell measurement for a single-electron spin qubit in a triple quantum dot utilizing the Pauli exclusion principle to create and detect maximally entangled states. The single spin polarization is teleported from the input qubit to the output qubit. We find this fidelity is primarily limited by singlet–triplet mixing, which can be improved by optimizing the device parameters. Our results may be extended to quantum algorithms with a larger number of semiconductor spin qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An electron spin qubit in semiconductor quantum dot1 is a promising building block for quantum computing. Recent progress has realized fundamental control on single and two qubits2,3,4,5. Implementing three-qubit algorithms6,7,8 is a significant step forward, as they include demonstrations of key primitive algorithms such as detection and correction of single bit-flip errors9 using a repetition code. Quantum teleportation10 (QT) is an attractive instance of three-qubit algorithms and has been demonstrated in many physical systems11,12,13,14, because it enables long-range quantum communication via quantum repeaters15, as well as computational models such as gate teleportation16 and measurement-based control9. In gate-defined quantum-dot spin qubits, however, a probabilistic QT protocol has been demonstrated only recently6, employing a SWAP operation9 in a Heisenberg spin chain to distribute quantum entanglement in a quadruple quantum dot.

Here we design a simple probabilistic QT protocol for a single-electron spin qubit, where an entangled state is distributed by direct transfer of a qubit with a linear ramp pulse in a semiconductor triple quantum dot (TQD) device. We show that the spin polarization of the input qubit is teleported to that of the output qubit when and only when we have access to the outcome of the Bell measurement, as expected for QT. We analyze possible error sources in our QT process based on the input–output relation and find that the teleportation infidelity originates primarily from the leakages of singlet states to and from spin-polarized triplet states in the preparation and the measurement of the singlets.

Results

The QT protocol

The key ingredients in QT protocol are coherent distribution and detection of an entangled state. Our QT protocol realizes these steps by rapid adiabatic passage17 employing a linear ramp of the detuning energy rather than two-qubit gate operations. Advantages of this approach are that the pulse sequence is less complex, and that the entire operation time is within nanoseconds under appropriate inter-dot tunnel couplings.

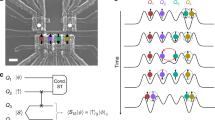

Figure 1a, b illustrate the sequence of the QT protocol. We teleport the state of an input qubit Q1 to the state of an output qubit Q3 using an ancillary qubit Q2 that is initially entangled with Q3. The top dot (QD1) hosts Q1 and the bottom dot (QD3) hosts Q3, whereas the middle dot (QD2) serves as a transport channel of Q2. First, the Q2–Q3 singlet state \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle = \frac{{\left| { \uparrow _2 \downarrow _3} \right\rangle - \left| { \downarrow _2 \uparrow _3} \right\rangle }}{{\sqrt 2 }}\) is prepared in QD3 by setting the Fermi level in the neighboring reservoir between the singlet and triplet levels in QD3. Next, Q2 is moved to QD2 and the Bell measurement of Q1 and Q2 is performed using Pauli spin blockade (PSB)17,18, where Q1 and Q2 are projected to the singlet state \(\left| {S_{12}} \right\rangle = \frac{{\left| { \uparrow _1 \downarrow _2} \right\rangle - \left| { \downarrow _1 \uparrow _2} \right\rangle }}{{\sqrt 2 }}\) only if Q2 can tunnel into QD1. On the other hand, when the tunneling of Q2 is blocked, they are projected to one of the triplet states. As the Bell measurement only distinguishes the singlet out of the four two-qubit basis states, QT is realized stochastically. This type of QT is called probabilistic QT.

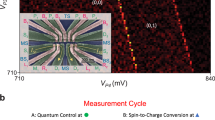

a Sequence for the demonstration of QT with markers representing the operation points in the stability diagram in d. The colored rectangular boxes represent individual steps using the pulse shapes shown in Fig. 2 with corresponding colors. b Schematic of our implemantation of the QT protocol. The spin state is teleported from a qubit in QD1 to that in QD3. A spin singlet is prepared in QD3 by adjusting the Fermi level in the reservoir to be between the singlet and triplet levels in QD3. After transfering one of the two electrons in QD3 into QD2, we use Pauli spin blockade (PSB) for the single-shot measurement of the two-spin state in QD1 and QD2 to distinguish whether it is singlet or not. To complete the QT protocol, we post-select the single-shot data conditioned on the singlet outcome. c Annotated scanning electron micrograph of the TQD similar to the one used for the experiment. A QD charge sensor with rf-reflectometry is used to detect the TQD charge states. d Charge stability diagram obtained by sweeping the voltages VPL and VPR on the gate electrodes PL and PR. The symbols represent the bias positions used for various operations in the QT experiment (see Figs. 2 and 3).

TQD device

A linearly coupled TQD19,20 is fabricated on a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure wafer as shown in Fig. 1c. We apply voltage pulses to the P1 and the P3 gates to rapidly control energy levels of the TQD. The measured lever arm along \({\it{\epsilon }}\) is about 30 μeV mV−1, where \({\it{\epsilon }}\) is defined as the energy difference between (2,0,1) and (1,0,2) (see Fig. 1d). A micromagnet fabricated on the wafer surface forms an inhomogeneous local magnetic field and enables addressable electric-dipole spin resonance (EDSR)3,21 control (see Supplementary Note 2). The local magnetic field is largest in QD1 followed in order by in QD2 and QD3 (the static external magnetic field is \(B_{{\mathrm{ext}}} = 3.07\) T and the resonance frequency in QD1 is 16.3 GHz). The local Zeeman field difference between QD1 and QD2 is \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_{12} = 500\) MHz, and the one between QD2 and QD3 is \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_{23} = 300\) MHz. We detect the electron charge configuration in the TQD by measuring the reflectometry signal (Vrf)22 of the nearby sensor dot. Figure 1d shows the charge stability diagram of the TQD around the charge states of (N1,N2,N3) = (1,1,1), (1,0,2), and (2,0,1) used in this work, where Ni denotes the number of electrons in QDi. The measured electron temperature is 150 mK (13 μeV), which is low enough to perform spin readout by energy-selective tunneling under the effective Zeeman splitting of about 64 μeV in QD3. It is noteworthy that we tune the inter-dot tunnel couplings tc with the larger one being 2 GHz for QD1 and QD2 so that direct spin–spin interaction between QD1 and QD3 in (1,1,1) is negligible (see Supplementary Note 1).

Ingredients of the QT protocol

The fidelity of the entire process of our QT protocol is subject to the tunnel coupling strengths, because our approach relies on the mapping between two-spin states and charge states by detuning ramps. In our protocol, we need to perform PSB between QD1 and QD2, where Q1 and Q2 are projected to \(\left| {S_{12}} \right\rangle\) only when the tunneling of Q2 into QD1 is allowed. Furthermore, we need to separate \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle\) into QD2 and QD3. However, these operations may fail because of the weak inter-dot tunnel couplings. For example, when the tunneling of Q2 from QD2 to QD1 is slow, we need a slow detuning ramp for the Bell measurement, which can cause mixing of \(\left| {S_{12}} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {T_{0,12}} \right\rangle\) during the ramp. Furthermore, the slow tunneling of Q2 from QD3 to QD2 during the \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle\) separation process can cause a transition to the excited singlet state and destroy the coherence of \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle\). To confirm the feasibility of \(\left| {S_{12}} \right\rangle\) detection, we perform the PSB measurement with QD1 and QD2 (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows the histogram of the single-shot PSB signal Vrf after loading an up spin to QD1 and a random spin into QD2. We use a latched readout technique to enhance the readout visibility, which transfers the spin-blocked (1, 1, 1) charge state to (2,1,1) before the readout23,24. The solid line is a fit using two noise-broadened Gaussian distributions considering the relaxation of triplet states18. The state is registered as singlet (triplet) when Vrf is lower (higher) than the threshold voltage, \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\). Next, we measure singlet–triplet oscillation (\(ST_0\) oscillation18,25, where T0 denotes non-polarized triplet) in QD2 and QD3 induced by \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_{23}\), to ensure the creation and separation of \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle\) (Fig. 2c). Figure 2d shows the measured singlet probability, \(P_{\mathrm{S}}\), as a function of the dwell time \(t_{{\mathrm{dwell}}}\) in (1,1,1). As the dwell point is far detuned from the (1,1,1)–(1,0,2) degeneracy point, the exchange coupling between Q2 and Q3 is suppressed and the observed periodic oscillation of PS indicates coherently repeated transitions between \(\left| {S_{23}} \right\rangle\) and \(|T_{0,23}\rangle\) (the oscillation visibility is largely limited by readout error arising from the relaxation of \(|T_{0,23}\rangle\), which does not contribute to the teleportation infidelity). These results (Fig. 2b, d) show that the device is properly set up to realize coherent separation of \(|S_{23}\rangle\) and projection measurement onto \(|S_{12}\rangle\).

a Detuning pulse shape represented for VPR used for the PSB measurement between (1,1,1) and (2,0,1). The detuning is first ramped by rapid adiabatic passage across the (1,1,1) and (2,0,1) resonance, and then instantly pulsed to the measurement point (marked by a pentagon) to avoid spin mixing at the anti-crossing of the singlet and the spin-up polarized triplet. b Histogram of the single-shot PSB measurement signal \(V_{{\mathrm{rf}}}\). The left population indicates (2,1,1) charge state and the right indicates (1,1,1) charge state. c Pulse shape used for preparing a singlet and measuring the \(ST_0\) oscillation in QD2 and QD3, while a random spin is left in QD1. A singlet initialized in QD3 at the triangle marker is separated at the square marker and subsequently measured by the ramp similar to the one used in a. The dwell point (marked by a square) is chosen so that the exchange interaction between Q2 and Q3 is negligible. d \(ST_0\) oscillation in QD2 and QD3. The solid line is a fit using the Gaussian decaying envelope. e Pulse shape for preparing and measuring the input qubit Q1. To load and measure \(\left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle\), the ramp is slower than those in a. An MW burst is applied at the point marked by a circle. f Rabi oscillation driven by the resonant SWAP using QD1 and QD2. The MW burst time \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\) is 4, 8, 12, …, 80 ns. Triangles indicate the values of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) obtained after correcting the readout errors in detecting \(\left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle\). Error bars represent the SE. The solid line is a fit using \(A_{{\mathrm{in}}}\cos \left( {2\pi f_{{\mathrm{in}}}t + \phi _{{\mathrm{in}}}} \right)e^{ - \left( {\frac{t}{{T_{2,{\mathrm{in}}}^{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}}}} \right)^2} + B_{{\mathrm{in}}}\) with \(A_{{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.17 \pm 0.02,\,B_{{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.57 \pm 0.02,\,f_{{\mathrm{in}}} = 13.1 \pm 0.8 \, {\mathrm{MHz}},\,T_{2,{\mathrm{in}}}^{{\mathrm{Rabi}}} = 86 \pm 13 \, {\mathrm{ns}}, \, \phi _{{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.18 \pm 0.2\). The low visibility is supposed to be due to initialization error of singlet in QD1, because gate voltages for setting the initialization point and dot-lead couplings are not optimal.

Preparation of input qubit and readout of output qubit

To prepare an input state for the QT protocol, we rotate Q1 using resonantly driven coherent oscillation. Although the micromagnet-mediated EDSR21 is useful for the qubit rotation, we find that Q1 can be manipulated faster with less decay by resonant SWAP26,27 using QD1 and QD2 in this particular device (see Supplementary Fig. 3 in Supplementary Note 2). To realize the resonant SWAP, we first load \(\left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle\) in QD1 and QD2 using slow adiabatic passage28 (Fig. 2e), where the double-line arrow (\(\Uparrow\) or \(\Downarrow\)) represents an extra spin in QD2, which is temporarily loaded to assist the rotation of Q1 and is later discarded to the reservoir. Then, resonant transitions between \(\left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle\) and \(\left| { \downarrow _1 \Uparrow } \right\rangle\) are driven by a microwave (MW) burst applied to the P2 gate. The resulting two-spin state is \(\alpha \left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle + \beta \left| { \downarrow _1 \Uparrow } \right\rangle\) with \(\left| \alpha \right|^2 \, + \, \left| \beta \right|^2 = 1\). By emptying QD2, the coherence of Q1 is lost but the probabilities in the up/down basis \(\left| \alpha \right|^2\) and \(\left| \beta \right|^2\) are retained. Therefore, an input state is a classical state with the density matrix \(\rho _1 = P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\left| { \uparrow _1} \right\rangle \left\langle { \uparrow _1} \right| + P_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\left| { \downarrow _1} \right\rangle \left\langle { \downarrow _1} \right|\), where \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = \left| \alpha \right|^2\) and \(P_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = \left| \beta \right|^2\). To estimate \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\), we measure the probability of \(\left| { \uparrow _1 \Downarrow } \right\rangle\) (\(P_ \uparrow ^{{\mathrm{raw}}}\)) after an MW burst by PSB (shown in Supplementary Fig. 3). \(P_ \uparrow ^{{\mathrm{raw}}}\) is modeled as \(P_ \uparrow ^{{\mathrm{raw}}} = f_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} + (1 - f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}})(1 - P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}})\) with the readout fidelities, \(f_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) and \(f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) for the spin-up and -down states. The readout fidelities are determined by two error sources: the state-mapping error and the electrical detection error. Here we ignore the state-mapping error, because our ramp time used for the readout (15 ns) is long enough given \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_{12} = 500\) MHz and \(t_{\mathrm{c}} = 2\) GHz between QD1 and QD2, but revisit this issue in “Discussion” section. By considering the electrical detection error based on the charge distinguishability of two Gaussian distributions (see Supplementary Note 3), we estimate the readout fidelities to be \(f_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.96\) and \(f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.90\). Figure 2f shows \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) as a function of the MW burst time \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\), indicating that we can vary the spin-up probability of the input state. The decay of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) for the longer \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\) is due to decoherence and relaxation, while the amplitude and the offset of the oscillation are influenced by the initialization error. It is noteworthy that those errors are irrelevant to the fidelity of our QT protocol.

The state of Q3 teleported from Q1 is read out by the spin-selective tunneling to the lower reservoir29. This readout is performed by pulsing gate voltages near the (2,0,1)–(2,0,0) transition line (marked by a star in Fig. 1d), where Q3 can tunnel out to the reservoir only when its spin is down. We estimate the output qubit readout fidelities for spin-up and -down state to be \(f_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}} = 0.83\) and \(f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{out}}} = 0.50\) from additional experiments and analytical calculation30 (see Supplementary Note 4). \(f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}\) is limited by a relatively small tunnel rate to the reservoir compared to the readout time. We estimate the spin-up probability by taking into account those infidelities—similar to Q1.

Demonstration of QT

We now integrate all the steps for the preparation of Q1, the QT protocol, and the final readout of Q3 in one sequence. Figure 3a shows the spin-up probability of Q3 obtained as a function of \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\) to drive Q1. The gray squares denote \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}\), the spin-up probability produced regardless of the Bell measurement outcome. \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}\) is independent of \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\), showing no correlation with the input qubit Q1. In contrast, if we extract the data set conditioned on the singlet outcome in the Bell measurement (classical information, CI), we obtain \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) (see blue circles in Fig. 3a), which reproduces the Rabi oscillation of Q1 (Fig. 2f). Here, \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\) of the Bell measurement is chosen to take full advantage of CI (see the black dashed line in Fig. 3b), i.e., to maximize the oscillation amplitude \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\). As the accuracy of the CI is degraded deliberately by raising \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\), a monotonic decrease of the amplitude is observed. These agree well with an essential property of the QT, that QT requires the local measurement of Q3 and the outcome of the Bell measurement to reproduce the original state of Q1. The similarity between \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) supported by the requirement of both the entangled state and the CI is the hallmark of successful teleportation.

a Spin-up probability of Q3 obtained as a function of the MW burst time \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\) (0, 2, 4, …, 80 ns) used to vary the spin orientation of Q1. Error bars represent the SE. Gray squares are \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}\) taken regardless of the outcome of the Bell measurement. The gray solid line is a fit to a constant value. Blue circles are \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) extracted from the data conditioned on the singlet outcomes of the Bell measurement. The blue solid line is a fit to \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\cos \left( {2\pi f_{{\mathrm{in}}}t + \phi _{{\mathrm{in}}}} \right)e^{ - \left( {\frac{t}{{T_{2,{\mathrm{in}}}^{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}}}} \right)^2} + B_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) with \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}} = 0.11 \pm 0.01\,{\mathrm{and}}\,B_{{\mathrm{out}}} = 0.69 \pm 0.02\), respectively. b Dependence of \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) on the threshold voltage \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\) in the Bell measurement. Error bars represent 68% confidence interval determined from the fit in \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\). The threshold voltage used in a is shown by a black dashed line. The upper panel shows the histogram of the Bell measurement signal \(V_{{\mathrm{rf}}}\). The lower panel shows \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) and the singlet probability, \(P_{\mathrm{S},{\mathrm{Bell}}}\), as a function of \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\). \(V_{{\mathrm{rf}}}\) lower (higher) than \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\) is judged as singlet (triplet). As \(V_{{\mathrm{threshold}}}\) is increased, \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) decreases because the accuracy of the classical information decreases. On the left side of the black dashed line, \(A_{{\mathrm{out}}}\) decreases as the number of singlet outcomes in the Bell measurement decreases and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) cannot be fitted well.

Discussion

We consider the spin-up probability of Q3, \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\), expected from the estimated values of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}}\) and the error model of our QT protocol discussed below. Pink triangles in Fig. 4 show the direct comparison of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) with \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\), assuming that there are no errors in the operations for our QT protocol. The discrepancy between the two, namely the deviation from the red line, allows us to infer possible errors in the whole QT process. We discuss below the effects of the errors.

Horizontal error bars represent the SE. Vertical error bars represent error calculated using Eq. (5) with the SE of \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\). \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) is the one observed experimentally, whereas \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) is what is expected from the model. The red line shows the ideal case when \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) are identical. \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) is obtained by averaging the scattered data points at each \(t_{{\mathrm{burst}}}\) in Fig. 3a for clarity. \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) is calculated by assuming no errors in the whole process of the QT protocol (pink triangles), finite errors in preparation and detection of singlet (orange squares), and an additional mapping error in the input qubit readout (blue circles), respectively. We use estimated values of \(F_{\mathrm{S},{\mathrm{Bell}}} - F_{T_0,{\mathrm{Bell}}} = 0.38\), \(F_{{\Phi},{\mathrm{Bell}}} = 0.96\), \(\left| \delta \right|^2 = 0.51\), and \(\left| \zeta \right|^2 = 0.05\) (for orange squares and blue circles), and \(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \uparrow }\) (\(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \downarrow }\)) \(= 0.90\) (\(0.93\)) (for blue circles).

First, an error may occur in the singlet preparation step during the transition of Q2 from QD3 to QD2. The prepared two-spin states in QD2 and QD3 are described by a combination of \(\left| { \uparrow _2 \downarrow _3} \right\rangle\), \(\left| { \downarrow _2 \uparrow _3} \right\rangle\), \(\left| { \uparrow _2 \uparrow _3} \right\rangle\), and \(\left| { \downarrow _2 \downarrow _3} \right.\). However, the leakage to \(\left| { \downarrow _2 \downarrow _3} \right\rangle\) is unlikely, because this state has much higher energy throughout the QT protocol due to the large magnetic field. On the other hand, \(\left| { \uparrow _2 \uparrow _3} \right\rangle\) may be mixed with \(|S_{23}\rangle\) due to the transverse magnetic field difference \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_x\) at their degeneracy point during the ramp from (1,0,2) to (1,1,1). As this transition is coherent31,32, the prepared state is described as

with \(\left| {\upgamma} \right|^2 \, + \, \left| {\updelta} \right|^2 \, + \, \left| \zeta \right|^2 = 1\). Here, the perfect singlet preparation would lead to \({\upgamma} = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\), \(\delta = - \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\), and \(\zeta = 0\).

The second source of error is in the detection process. This can be decomposed to the state-mapping error and the electrical detection error in the Bell measurement. The latched readout technique employed here helps to suppress the electrical detection error to 0.02 but a state-mapping error in transferring the spin-blocked (1,1,1) to (2,1,1) may remain due to the nonideal dot-to-lead tunnel rates23,33. This error is modeled by using the measurement operator

where \(1 - F_{S,{\mathrm{Bell}}}\), \(1 - F_{T_0,{\mathrm{Bell}}}\), and \(1 - F_{{\Phi},{\mathrm{Bell}}}\) are the detection errors of the singlet S, the non-polarized triplet T0, and the other two Bell states \({\Phi}^ \pm\).

Using Eqs. (1) and (2), we now calculate the final spin-up probabilities of Q3 with and without CI, \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{model}}}\), respectively (see Supplementary Note 5). The density matrix of the three-qubit state before the Bell measurement is expressed as \(\rho _{123} = \rho _1 \otimes \rho _{23}\), where \(\rho _{23}\) is the density matrix of Q2 and Q3, and is given by \(\rho _{23} = \left| {{\Psi}_{23}} \right\rangle \left\langle {{\Psi}_{23}} \right|\). The probability of finding the singlet outcome in the Bell measurement is then given by

where \(p_{\mathrm{S}} = {\mathrm{Tr}}\left( {\rho _{123}\left| {S_{12}} \right\rangle \left\langle {S_{12}} \right|} \right)\) is the ideal probability of detecting S and \(p_{T_0({\Phi})}\) is defined similarly. It is noteworthy that \(P_{\mathrm{S},{\mathrm{Bell}}}^{{\mathrm{model}}}\) depends on the state of Q1 unless the preparation of singlet is perfect. Using this notation, we obtain

where \({\mathrm{Tr}}_{12}\) denotes the partial trace over Q1 and Q2. To infer the error values, we now compare Eqs. (3)–(5) with experimental results. By minimizing the deviations between \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{model}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}\), between \(P_{S,{\mathrm{Bell}}}^{{\mathrm{model}}}\) and \(P_{S,{\mathrm{Bell}}}\), and finally between \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\), we arrive at \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) shown by orange squares in Fig. 4 with \(F_{\mathrm{S},{\mathrm{Bell}}} - F_{T_0,{\mathrm{Bell}}} = 0.38\), \(F_{{\Phi},{\mathrm{Bell}}} = 0.96\), \(\left| \delta \right|^2 = 0.51\), and \(\left| \zeta \right|^2 = 0.05\). \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) and \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) now match each other reasonably well, but there remains a noticeable discrepancy. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the state-mapping error in the PSB readout of Q1 mentioned before, which needs to be taken into account in \(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \uparrow }\) and \(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \downarrow }\). Indeed, when we assume \(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \uparrow } = 0.90\) and \(f_{{\mathrm{in}}, \downarrow } = 0.93\) (instead of \(f_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.96 \pm 0.01\) and \(f_{ \downarrow ,{\mathrm{in}}} = 0.90 \pm 0.01\)), we find \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}},{\mathrm{model}}}\) agrees well with \(P_{ \uparrow ,{\mathrm{out}}}^{{\mathrm{CI}}}\) (see blue circles falling on the red line in Fig. 4).

Finally, we predict the fidelity of the QT protocol using the inferred error values. We anticipate that our protocol could teleport an arbitrary input state coherently, because the 2 ns ramp time from (1,0,2) to (2,0,1) is sufficiently shorter than the measured dephasing time of 21 ± 1 ns in the device. A complete fidelity analysis may be performed by quantum tomography experiments, in combination with the techniques to suppress the effect of fluctuating nuclear fields, which degrades tomographic rotation of qubits34. In the meanwhile, the classical fidelities give useful information about the main error sources in the QT protocol. We define the classical fidelity to be the probability of finding the spin-up (-down) output qubit for the spin-up (-down) input qubit. The error values obtained in the above suggest the fidelities of \(F_ \uparrow = 0.95\) and \(F_ \downarrow = 0.86\). The fact that \(F_ \uparrow\) is close to 1 and \(F_ \downarrow\) is much lower than \(F_ \uparrow\) suggests that the effect of a finite \(T_ +\) component (\(\zeta\)) in the prepared singlet pair in Q2 and Q3 is large, because \(T_ +\) leads to a bit-flip error only for the spin-down input, whereas erroneous detection of \({\Phi}^ \pm\) as singlet results in a bit-flip error regardless of the input qubit state. We therefore conclude that the main error source of the classical infidelity is leakage to \(T_ +\) in the preparation process of the singlet state.

We note that the design of the magnetic field gradient induced by the micromagnet is crucial for the teleportation fidelity. The spin mixing between the ground singlet and \(T_ +\) may be caused by the transverse magnetic field difference \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_x\) between adjacent QDs. The micromagnet in our device induces large \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_x\), because its geometry is asymmetric around the TQD axis35. In addition, it is desirable to reduce \({\mathrm{{\Delta}}}B_z\) to mitigate the effect of ST0 mixing during the measurement and combine the latched readout technique, which increases \(F_{T_0,{\mathrm{Bell}}}\)23. Although this does not improve the classical fidelities \(F_ \uparrow\) and \(F_ \downarrow\), it is important for the quantum mechanical fidelity in coherent teleportation.

In summary, we demonstrate a simple and efficient protocol of the probabilistic QT for a quantum-dot spin qubit. The ground-state initialization of a doubly occupied dot, together with a simple pulsed control of the detuning energy, allows for the preparation of an entangled state and the Bell measurement. The statistics of the spin polarization of the output qubit conditioned on the outcome of the Bell measurement reproduces that of the input qubit, demonstrating that the spin orientation is teleported from the input qubit to the output qubit. Given the short operation time, we expect that our QT protocol could teleport an arbitrary quantum state, although a quantum tomography experiment is necessary for its demonstration. We find that the main error source in this protocol is the mixing of the entangled states with \(T_ +\) substantially due to the large magnetic field gradients, which may be improved by optimizing the device design. Our demonstration is among the first demonstrations of teleportation with a single-electron spin qubit in semiconductor quantum dots. Our results open a path to demonstrate quantum algorithms with three or more qubits in semiconductor electron spin qubits.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that is deemed central to the conclusions are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Loss, D., DiVincenzo, D. P. & DiVincenzo, P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120–126 (1998).

Koppens, F. H. L. et al. Driven coherent oscillations of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 442, 766–771 (2006).

Yoneda, J. et al. A quantum-dot spin qubit with coherence limited by charge noise and fidelity higher than 99.9%. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 102–106 (2018).

Veldhorst, M. et al. A two-qubit logic gate in silicon. Nature 526, 410 (2015).

Huang, W. et al. Fidelity benchmarks for two-qubit gates in silicon. Nature 569, 532–536 (2019).

Qiao, H. et al. Conditional teleportation of quantum-dot spin states. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020).

Takeda, K. et al. Quantum tomography of an entangled three-spin state in silicon. Preprint at arxiv https://arxiv.org/cond-mat/2010.10316 (2020).

Hendrickx, N. W. et al. A four-qubit germanium quantum processor. Nature 591, 580–585 (2021).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895–1899 (1993).

Bouwmeester, D. et al. Experimental quantum teleportation. Nature 390, 575–579 (1997).

Furusawa, A. Unconditional quantum teleportation. Science 282, 706–709 (1998).

Steffen, L. et al. Deterministic quantum teleportation with feed-forward in a solid state system. Nature 500, 319–322 (2013).

Pfaff, W. et al. Unconditional quantum teleportation between distant solid-state quantum bits. Science 345, 532–535 (2014).

Gisin, N., Ribordy, G., Tittel, W. & Zbinden, H. Quantum cryptography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 145–195 (2002).

Gottesman, D. & Chuang, I. L. Demonstrating the viability of universal quantum computation using teleportation and single-qubit operations. Nature 402, 390–393 (1999).

Petta, J. R. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science 309, 2180–2184 (2005).

Barthel, C., Reilly, D. J., Marcus, C. M., Hanson, M. P. & Gossard, A. C. Rapid single-shot measurement of a singlet-triplet qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 160503 (2009).

Noiri, A. et al. A fast quantum interface between different spin qubit encodings. Nat. Commun. 9, 5066 (2018).

Nakajima, T. et al. Quantum non-demolition measurement of an electron spin qubit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 555–560 (2019).

Yoneda, J. et al. Fast electrical control of single electron spins in quantum dots with vanishing influence from nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 267601 (2014).

Reilly, D. J., Marcus, C. M., Hanson, M. P. & Gossard, A. C. Fast single-charge sensing with a rf quantum point contact. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 1–4 (2007).

Nakajima, T. et al. Robust single-shot spin measurement with 99.5% fidelity in a quantum dot array. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 017701 (2017).

Harvey-Collard, P. et al. High-fidelity single-shot readout for a spin qubit via an enhanced latching mechanism. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021046 (2018).

Nakajima, T. et al. Coherent transfer of electron spin correlations assisted by dephasing noise. Nat. Commun. 9, 2133 (2018).

Shulman, M. D. et al. Suppressing qubit dephasing using real-time Hamiltonian estimation. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–6 (2014).

Nichol, J. M. et al. High-fidelity entangling gate for double-quantum-dot spin qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 1–4 (2017).

Noiri, A. et al. Coherent electron-spin-resonance manipulation of three individual spins in a triple quantum dot. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 153101 (2016).

Elzerman, J. M. et al. Single-shot read-out of an individual electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 430, 431–435 (2004).

Keith, D. et al. Benchmarking high fidelity single-shot readout of semiconductor qubits. N. J. Phys. 21, 063011 (2019).

Chesi, S. et al. Single-spin manipulation in a double quantum dot in the field of a micromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 90, 235311 (2014).

Petta, J. R., Lu, H. & Gossard, A. C. A coherent beam splitter for electronic spin states. Science 327, 669–672 (2010).

Zhao, R. et al. Single-spin qubits in isotopically enriched silicon at low magnetic field. Nat. Commun. 10, 5500 (2019).

Nakajima, T. et al. Coherence of a driven electron spin qubit actively decoupled from quasistatic noise. Phys. Rev. X 10, 11060 (2020).

Yoneda, J. et al. Robust micromagnet design for fast electrical manipulations of single spins in quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Express 8, 084401 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Part of this work is financially supported by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST), Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (JPMJCR1675 and JPMJCR15N2), the ImPACT Program of Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP26220710, JP18H01819, JP19K14640, and JP17K14078), a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (JP20J12862), and The Murata Science Foundation. Y.K. acknowledges support from Materials Education program for the future leaders in Research, Industry, and Technology (MERIT). T.O. acknowledges support from PRESTO (JPMJPR16N3), JST, Telecom Advanced Technology Research Support Center. A.L. and A.D.W. gratefully acknowledge financial support from grants DFH/UFA CDFA05-06, DFG TRR160, DFG project 383065199, and BMBF Q.Link.X 16KIS0867.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.K., T.N., and S.D.B. conceived and designed the experiment. T.N. and A.N. fabricated the device on the heterostructure grown by A.L. and A.D.W. Y.K. and T.N. performed the measurement and data analysis with the inputs from A.N., J.Y., and K.T. Y.K. and T.N. wrote the manuscript with inputs from other authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. The project was supervised by S.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kojima, Y., Nakajima, T., Noiri, A. et al. Probabilistic teleportation of a quantum dot spin qubit. npj Quantum Inf 7, 68 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00403-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-021-00403-4

This article is cited by

-

Progress in quantum teleportation

Nature Reviews Physics (2023)

-

Review of performance metrics of spin qubits in gated semiconducting nanostructures

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

-

Quantum State Recovery Via Environment-assisted Measurement and Weak Measurement

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2022)

-

Cyclic controlled remote state preparation protocol initiated by a mentor for qubits

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2022)

-

Optimal teleportation via a non-maximally entangled channel in qutrits system

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2021)