Abstract

Nitrogen vacancy (NV) centers, optically active atomic defects in diamond, have attracted tremendous interest for quantum sensing, network, and computing applications due to their excellent quantum coherence and remarkable versatility in a real, ambient environment. One of the critical challenges to develop NV-based quantum operation platforms results from the difficulty in locally addressing the quantum spin states of individual NV spins in a scalable, energy-efficient manner. Here, we report electrical control of the coherent spin rotation rate of a single-spin qubit in NV-magnet based hybrid quantum systems. By utilizing electrically generated spin currents, we are able to achieve efficient tuning of magnetic damping and the amplitude of the dipole fields generated by a micrometer-sized resonant magnet, enabling electrical control of the Rabi oscillation frequency of NV spins. Our results highlight the potential of NV centers in designing functional hybrid solid-state systems for next-generation quantum-information technologies. The demonstrated coupling between the NV centers and the propagating spin waves harbored by a magnetic insulator further points to the possibility to establish macroscale entanglement between distant spin qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The past decade witnessed significant progress in new approaches for information processing, such as quantum1, neuromorphic2,3, and non-von Neumann computing4. This research interest is fueled by the saturation of downscaling and speed of the conventional CMOS technology and the energy use of current information technologies. Among these potential candidates, quantum computing employs algorithms that rely on inherent quantum properties of microscopic matter such as coherence, superposition, and entanglement and serves as a transformative platform enabling massively parallel processing of information in a compact physical system5. Many promising quantum systems including superconducting Josephson junctions6, topological insulators7, and trapped ions8 have been extensively explored toward this end.

Nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers9, optically active atomic defects in diamond that act as single-spin quantum bits, are naturally relevant in this context. Due to their excellent quantum coherence time9, local spin-entanglement10, and notable versatility in a wide temperature range11,12, NV centers offer a remarkable platform to design emerging quantum architectures13,14,15. They have been successfully applied to quantum sensing, imaging, and quantum networks, exhibiting unprecedented field sensitivity9, spatial resolution16, and long-range photon-mediated qubit transmission17. Despite the remarkable progress, the role of NV centers in quantum computing has been peripheral. One of the major bottlenecks results from difficulties in locally addressing individual NV spin states in a scalable, energy-efficient manner. Presently, the quantum spin states of an individual NV center are mainly controlled by microwave fields generated by electric currents in a proximal metallic stripline or waveguide18. The dispersive Oersted fields slowly decay in real space, which imposes an inherent challenge to achieve scalability in NV-based quantum operation systems. In addition, this approach typically requires a high microwave current density and the associated Joule heat can lead to decoherence of the quantum spin states19. While alternative approaches such as mechanical resonators20,21,22, magnetoelastic interaction23, and strain20,21,22 have been explored recently, the desirable scalability or coupling strength are lacking in these schemes.

In this article, we report energy-efficient electrical control of single-spin rotation in a hybrid NV-magnet quantum system. The resonant spin waves excited in a proximal magnetic insulator, yttrium iron garnet (YIG), effectively amplify the amplitude of local microwave fields at the NV site, giving rise to orders of magnitude enhancement of the NV spin rotation rate. By utilizing the spin-orbit torque (SOT) generated by an adjacent platinum (Pt) layer24,25,26, we further demonstrated an efficient tuning of the magnetic damping of the resonant spin waves, enabling electrical control of spin rotation of a single-spin quantum qubit. We note that the mutual interactions between spin currents, magnetic devices, and NV spin qubits could be controlled in a scalable fashion down to a nanoscale regime, offering a new route to develop NV-based hybrid quantum computing platforms.

Results

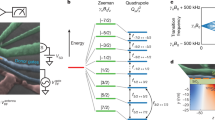

Ferromagnetic resonance assisted NV spin rotation

We first discuss the measurement system and device structure as illustrated in Fig. 1a. A 10-μm-wide and 50-μm-long YIG/Pt strip was fabricated by standard photolithography and ion mill etching processes from a Gd3Ga5O12 (substrate)/YIG (20 nm)/Pt (10 nm) film. A diamond nanobeam27 containing individually addressable NV centers was transferred onto the surface of the YIG/Pt strip to establish nanoscale proximity between NV spins and the studied samples (see Supplementary Note 1). The diamond nanobeams used in this work have a shape of an equilateral triangular prism with approximate dimensions of 500 nm × 500 m × 10 μm, which are fabricated following a top-down etching and an angle-etching procedure27. A 500-nm-thick on-chip Au stripline was fabricated next to the YIG/Pt strip, delivering microwave currents to manipulate the NV spin state and to excite ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) of the YIG strip. We employed a scanning confocal microscope to optically locate NV centers. A photoluminescence (PL) image shown in Fig. 1b provides an overview of the device structure, where an NV center (NV1) is positioned on top of the YIG/Pt strip, demonstrating the single-spin addressability. We first performed optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) measurements to examine the NV electron spin resonance (ESR) and the FMR of the patterned YIG strip. A green laser was applied to constantly initialize the NV spin to the ms = 0 state, and the emitted PL was monitored via a single-photon detector. An external magnetic field Bext was applied along the NV-axis, with an angle of 60° relative to the z-axis as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Figure 1c shows the normalized PL intensity as a function of the microwave frequency \(f\) and the external magnetic field Bext. The straight line denoted by \(f_ -\) results from the expected decrease in NV fluorescence of NV ESR transition in the electronic ground state: \(f_ -\) = 2.87 \(- \gamma B_{{\mathrm{ext}}}/2{\uppi}\), where \(\gamma\) is the gyromagnetic ratio. The other two straight lines denoted by \(f_{{\mathrm{e}} \pm }\) result from the NV ESR at the optically excited state: \(f\!_{{\mathrm{e}} \pm }\) = 1.42 ± \(\gamma B_{{\mathrm{ext}}}/2{\uppi}\). The NV fluorescence also decreases when \(f\) matches the FMR frequency \(f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) of the YIG strip as shown by the curved dash line below \(f_{{\mathrm{e}} + }\). This NV-based off-resonant detection of spin wave modes in a proximal ferromagnet is attributed to multi-magnon scattering processes, giving rise to enhanced magnon densities at the NV ESR frequencies28,29,30.

a Schematic of an nitrogen vacancy (NV) spin positioned on top of a patterned Y3Fe5O12 (20 nm)/Pt (10 nm) strip to investigate the amplification and electrical tuning effect of the NV spin rotation rate at the Y3Fe5O12 (YIG) ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) condition. b A photoluminescence (PL) image showing an overview of a fabricated device consisting of an Au stripline (false yellow color) and a diamond nanobeam containing individually addressable NV spins on top of the YIG/Pt strip (false-silver color). The scale bar corresponds to 5 µm. c Normalized PL intensity of NV1 measured as a function of Bext and microwave frequency f. The black straight lines represent the NV electron spin resonance transitions in the electronic ground (excited) state and the white dash line represents the field dispersion curve of the YIG FMR mode. The time-dependent PL intensity of NV1 measured at d \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) ± 50 Hz and e \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\).

Next we performed NV Rabi oscillation measurements to characterize the coherent spin rotation rate \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) of NV1. When a microwave magnetic field with NV ESR frequencies \(f_ \pm\) is applied at the NV site, the NV spin will periodically oscillate between two different states, i.e. ms = 0 and ms = 1 or ms = 0 and ms = −1, in the rotation frame, which is referred to as Rabi oscillations31. Here, \(f_ \pm\) characterizes NV ESR frequencies corresponding to the spin transition between ms = 0 and ms = ±1 states. The coherent spin rotation rate \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) is proportional to the amplitude of the local microwave field that is perpendicular to the NV-axis30,32. Figure 1d, e show the measured PL intensity of NV1 as a function of the microwave duration time t at two different NV ESR frequencies. When \(f_ -\) is detuned from \(f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) by 50 MHz, the measured PL spectrum slowly oscillates with a characteristic \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) of 0.8 MHz, from which the local microwave field \(h_{{\mathrm{rf}}}\) generated by the Au stripline is estimated to be 0.5 Oe. Notably, when \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\), the NV PL spectrum exhibits a significantly accelerated oscillation behavior with an enhancement of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) from 0.8 to 9 MHz. This one order of magnitude enhancement of the NV coherent spin rotation rate results from a larger oscillating stray field \(h_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) generated by the quasi-uniform precession of the YIG magnetization, which amplifies the effective microwave magnetic field experienced by the NV spin (see Supplementary Note 2).

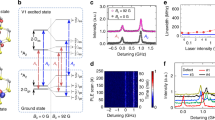

Electrical control of NV spin rotation

To achieve electrical control of the coherent NV spin rotation rate, we further employed the SOT generated by the Pt layer to vary the amplitude of the oscillating stray field \(h_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) generated by the resonant YIG strip. Figure 2a illustrates the optical, microwave, and electrical measurement sequence. A 3-μs-long green laser pulse was first applied to initialize the NV spin to the ms = 0 state. A microwave pulse at a frequency \(f_ -\) was applied to induce an ms = 0 ↔ −1 transition. To minimize the current-induced Joule heat, an electric current sequence synchronized with the microwave pulse was applied in the Pt layer. Last, a second green laser pulse was applied to measure the spin-dependent PL of the NV center and re-initialize the NV spin for the next measurement sequence. The time duration of the microwave (electrical) pulses systematically varies from zero to a few hundred nanoseconds in order to detect a time-dependent variation of the NV PL intensity. Figure 2b shows the Rabi oscillation spectrum of NV1 measured at three different electric current densities Jc when \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\). Without applying an electric current, \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) is measured to be 9 MHz, exhibiting a significant enhancement in comparison to the off-FMR condition as discussed above. When Jc = −1 × 1011 A/m2, we observed a faster oscillation behavior of the measured PL spectrum with an enhanced \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) = 11 MHz. When Jc = 1 × 1011 A/m2, the NV spin exhibits a slower oscillation behavior with a reduced \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) of 7 MHz. To further illustrate the electrical tuning and amplification effect at the YIG FMR condition, Fig. 2c plots the normalized NV Rabi frequency (\(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\)) as a function of \(f_ - - f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) when Jc = 0 and ±1 × 1011 A/m2. Note that the variation of the input microwave power P needs to be normalized to characterize the driving efficiency of NV spin rotation (see Supplementary Note 3). Figure 2d plots \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) measured at \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) as a function of the electric current density. In general, \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) follows a quasi-linear dependence on Jc and exhibits ~±23% variation when Jc = ±1 × 1011 A/m2.

a Schematic of the measurement sequence to electrically control nitrogen vacancy (NV) Rabi frequency. b The time-dependent photoluminescence intensity of NV1 measured at Jc = 0 and ±1 × 1011 A/m2. c Normalized NV Rabi frequency \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) measured as a function of \(f_ - - f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\). The green, blue, and red curves correspond to Jc = 0 and ±1 × 1011 A/m2, respectively. d When \(f_ - = f_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\), the measured current density dependence of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) (red points) agrees well with the theoretical prediction based on the spin-orbit-torque-model (blue line).

The electrically tunable \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}\) results from the SOT-induced variation of the local microwave magnetic field at the NV site. When an electric current flows through the Pt layer, a spin current Js is generated by the spin Hall effect33. Due to the interfacial scattering process, Js will transport across the YIG/Pt interface and thereby exerts a damping-like spin-transfer torque \(\tau {\boldsymbol{ = m}} \times ({\boldsymbol{m}} \times {\boldsymbol{s}})\) on the YIG magnetization. Here, \({\boldsymbol{m}}\) is the magnetization of the YIG pattern and \({\boldsymbol{s}}\) is the spin polarization of the injected spin currents. Depending on the polarity of the electric current, the magnitude of τ effectively increases or decreases the precessional cone angle \({\Theta}\) of the YIG magnetization, leading to a variation of the amplitude of the oscillating stray field \(h_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\) as follows: \(h_{{\mathrm{FMR}}}\)\(\propto\)\(M_{\mathrm{s}}\) sin\({\Theta}\). According to the SOT model, the electric current density dependence of \({\Theta}\) is given by24,25:

where ΔH0 is the film inhomogeneity contribution to the FMR linewidth, μ0 is the free-space permeability, \(\hbar\) is the reduced Planck constant, \(\alpha\), \(M_{{\mathrm{eff}}}\), \(M_{\mathrm{s}}\), and \(t_{{\mathrm{YIG}}}\) correspond to the intrinsic magnetic damping, effective demagnetizing field, saturation magnetization, and thickness of the YIG strip, respectively. \(\varphi\) characterizes the angle between the in-plane projection of the YIG magnetization and the applied electric current, \(\kappa\) characterizes the spin transport efficiency at the YIG/Pt interface25, and \(\theta _{{\mathrm{SH}}}\) is the spin Hall angle of the Pt layer. Taking \(\theta _{{\mathrm{SH}}}\) = 0.0733, \(\kappa\) = 0.25 with other known material parameters (\({\Delta} H_0\) = 6.3 Oe, \(\alpha\) = 0.001, and Ms = \(M_{{\mathrm{eff}}}\) = 1.31 × 105 A/m), the blue curve in Fig. 2d plots the current density dependence of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) predicted by the SOT-model, which is in excellent agreement with our experimental results.

Control of NV spin rotation by propagating spin wave modes

So far, we have demonstrated the electrical control of coherent spin rotation of an NV single spin by the quasi-FMR spin wave mode of a proximal ferromagnet. Next, we further extend the measurement platform to a more general scenario, where propagating spin waves with specific wavevectors and group velocities are involved. Figure 3a shows the schematic of the device structure, where an Au coplanar waveguide (CPW) and an insulating SiOx spacer are fabricated on a patterned 80-μm-wide and 300-μm-long YIG (100 nm)/Pt (10 nm) waveguide. The width of the signal and ground lines of the CPW and the center-to-center separation between them are 1.5 and 3.15 μm, respectively, and the long-axis of the CPW is perpendicular to the YIG waveguide as shown by the scanning electron microscope image of Fig. 3b. A diamond nanobeam containing an individual NV center (NV2) was transferred on top of the Pt layer with a distance of ~5.5 μm to the center of signal line. An external magnetic field Bext was applied along the long-axis of the CPW to excite the Damon-Eschbach surface spin wave mode34 at the YIG/Pt interface. The propagating nature of the excited spin wave has been experimentally confirmed by the measurements of microwave transmission between the two CPWs (see Supplementary Note 4). Figure 3c plots the characteristic wavevector spectrum. The well-defined excitation peaks are determined by the spatial distribution of the microwave fields generated by the CPW (see Supplementary Note 5)35. Figure 3d shows the ODMR map measured by the NV spin sensor, where up to four propagating surface spin wave modes with distinct wavevectors: k1, k2, k3, and k4 emerge. The field dispersion curves of these spin wave modes follow the theoretical prediction as shown by the white dash lines (see Supplementary Note 5) and cross with the NV ESR frequency \(f_ -\) between 2.1 and 2.6 GHz.

a Schematic of the nitrogen-vacancy-Y3Fe5O12/Pt device to establish a coherent coupling between propagating spin waves and the nitrogen vacancy (NV) spin. b Scanning electron microscope image of a prepared device with a patterned Y3Fe5O12 (YIG) waveguide and two coplanar waveguides (CPWs) to excite propagating surface spin waves. An electric current flowing through the Pt layer is employed to generated spin currents, enabling control of magnetic damping and amplitude of the excited spin waves. G and S represent ground and signal lines, respectively. The scale bar corresponds to 50 µm. c Spin-wave excitation spectra obtained by Fourier transformation of the microwave fields generated by the CPW. d Normalized photoluminescence intensity of the NV center as a function of Bext and microwave frequency f. The two black straight lines correspond to the NV electron spin resonance transitions and the four white dash lines correspond to the field dispersion curves of propagating surface spin wave modes with characteristic wavevectors of k1, k2, k3, and k4.

To illustrate the amplification effect of the propagating spin waves on the NV spin rotation rate, the red curve in Fig. 4a shows \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) measured as a function of \(f_ -\). Remarkably, \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) reaches the peak values of 15531, 16509, 5774, and 1977 MHz/\(\sqrt {{\mathrm{mW}}}\) when \(f_ -\) meets the resonant condition of the k1, k2, k3, and k4 spin wave modes, respectively. As a comparison, the gray curve shows \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) measured in the high magnetic field regime where \(f_ -\) stays far away from the resonant frequencies of the series of spin wave modes as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 4a. At the off-resonant condition, \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) follows an average value of 120 MHz/\(\sqrt {{\mathrm{mW}}}\). The enhancement ratio of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) reaches 129, 138, 48, and 17 at the resonant condition of k1, k2, k3, and k4 spin wave modes, respectively, in quantitative agreement with the theoretical calculations36 (see Supplementary Note 2). We notice that the enhancement of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) decreases with increasing wavevector, which is attributable to a reduced microwave excitation efficiency of the higher order propagating spin wave modes37. Similar to the quasi-FMR spin wave mode, we also employ spin currents generated by the Pt layer as a tuning knob to electrically control the NV spin rotation rate. Figure 4b plots the variation of \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) as a function of Jc at the resonant condition of the k1 and k2 spin wave modes. The normalized NV Rabi frequencies exhibit a systematic variation on the magnitude of Jc, in agreement with the SOT model predicted by Eq. (1). The reduced electrical tunability of NV spin rotation rate results from a much larger thickness of the YIG film as well as the higher resonant frequencies and wave vector of the propagating spin wave modes38. In addition to the surface spin wave modes, we also observed the similar behaviors for back volume spin wave modes when the external magnetic field is parallel to the short-axis of the CPWs, confirming the universality of the coupling between NV spins and the propagating magnons (see Supplementary Note 6).

a Normalized nitrogen vacancy (NV) spin rotation rate \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}/\sqrt P\) measured as a function of \(f_ -\) in the low magnetic field (red curve) and high magnetic field (gray curve) regimes. Inset: the variation of the NV electron spin resonance frequencies \(f_ \pm\) (black curves) and the resonant frequencies of propagating surface spin waves (green curves) as a function of Bext. b \(f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}(J_c)/f_{{\mathrm{Rabi}}}(J_c = 0)\) measured as a function of Jc at the resonant condition of k1 (red points) and k2 (blue points) spin wave modes. The red and blue curves plot the theoretical prediction based on the spin-orbit-torque-model.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated electrical control of the coherent spin rotation rate of a single-spin qubit in an NV-magnet quantum system. By applying an electric current in a YIG/Pt nanostructure, we observed a spin-current-induced variation of the Rabi frequency when the NV ESR frequency meets the resonant condition of spin wave modes. Further shrinking the dimension of the magnetic devices to sub-micrometer regime, where the generated spin currents could completely compensate the damping of the ferromagnet and excite the auto-oscillations39, the spin state of NV centers could be fully electrically addressed in absence of external microwave currents. We note that excellent quantum coherence is preserved in NV centers in this process. The measured spin coherent time is one order of magnitude larger than the reported value of nanodiamonds14 and comparable to NV spins contained in bulk diamond structures (see Supplementary Note 7)40, which shows promise for applications in sensitivity metrology41, quantum computing13, and communications17. The demonstrated dipole coupling between single the NV spin and the propagating spin waves also serves as an ideal medium to establish long-range entanglement between distant NV spin qubits42, offering a new opportunity in designing an NV-based quantum operation platform.

Methods

Materials and device fabrication

The 20-nm thick Y3Fe5O12 (YIG) films used in this work were deposited by magnetron sputtering on (111)-oriented Gd3Ga5O12 (GGG) substrates. The saturation magnetization is measured to be 1.31 × 105 A/m. The details of the growth parameters have been reported in a previous work43. The 100-nm thick YIG films were grown by liquid-phase epitaxy method and were commercially available from the company Matesy GmbH. The saturation magnetization is measured to be 1.35 × 105 A/m. Two types of nitrogen-vacancy (NV)-YIG/Pt devices prepared by standard photolithography, ion beam etching, and sputtering processes. For the device illustrated in Fig. 1a, a 10-μm-wide and 50-μm-long YIG (20 nm)/Pt (10 nm) strip was first defined on a GGG substrate, followed by the fabrication of a 19.6-μm-wide and 500-nm thick Au stripline. For the device illustrated in Fig. 3a, a 80-μm-wide and 300-μm-long YIG (100 nm)/Pt (10 nm) waveguide was first created and Au CPWs were fabricated on the defined YIG waveguide with the perpendicular orientation. Patterned diamond nanobeams containing NV centers were picked up and transferred onto the magnetic nanostructures using a tungsten tip performed under a micromechanical transfer stage. Nanobeams were fabricated by a combination of top-down etching and angled etching processes27. Acid cleaning was performed before and after the fabrication processes to ensure a pristine diamond surface, which is crucial to establish nanoscale proximity between NVs and the studied samples.

NV measurements

NV measurements were performed by a home-built scanning confocal microscope. Green laser pulses used for the NV initiation and readout were generated by an acoustic optical modulator with a double-pass configuration. NV spin state was optically addressed through integrating the measured photoluminescence (PL) generated during the first 600 ns of the green laser readout pulse. NV Rabi oscillation measurements were performed using the sequence shown in Fig. 2a in the main text. The microwave signals were generated by a Rohde & Schwarz SGS100a and/or an Agilent N9310A and connected to a microwave switch (Minicircuits ZASWA-2-50DR+) and an amplifier (with +50 dB amplification, Minicircuits ZHL-25W-63+). The pulses to trigger the modulation of microwave amplitude (on and off) were generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (Tektronix AWG5014C). It was also used to apply the synchronized electrical pulses in the Pt layer to minimize the thermal heating effect (see supplementary note 8). The trigger pulses to the optical modulator and photon counting were generated by a programmable pulse generator (Spincore, PBESR-PRO-500).

COMSOL multiphysics simulations

“Electromagnetic Waves, Frequency Domain” module was used to simulate the spatial profile of the microwave magnetic fields generated by an Au CPW on top of a YIG thin film. Electric currents following through the signal and ground lines of the CPW were set to be +I, −I/2, and −I/2, respectively. Equilateral triangular meshes with varying dimensions were used in the simulations. In the area that is in the vicinity of the CPW, fine meshes with a length of 0.4 μm were used. We set a growth rate of the mesh size to have large meshes with a length of 40 μm in the area that is far away from the CPW. By solving the Helmholtz Equation, we could obtain the distribution of the magnetic fields in real space. The spin-wave excitation spectra in the momentum space was extracted via Fourier transformation of the magnetic field profile (see Supplementary Note 5).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All code not included in the paper are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2000).

Monroe, D. Neuromorphic computing gets ready for the (really) big time. Commun. ACM 57, 13 (2014).

del Valle, J. et al. Subthreshold firing in Mott nanodevices. Nature 569, 388–392 (2019).

Von Neumann, J. First draft of a report on the EDVAC. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 15, 27–75 (1993).

Bravyi, S., Gosset, D. & König, R. Quantum advantage with shallow circuits. Science 362, 308–311 (2018).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: An Outlook. Science 39, 1169–1174 (2013).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computations with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091–4094 (1995).

Rondin, L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 056503 (2014).

Dolde, F. et al. Room-temperature entanglement between single defect spins in diamond. Nat. Phys. 9, 139–143 (2013).

Liu, G. Q., Feng, X., Wang, N., Li, Q. & Liu, R. B. Coherent quantum control of nitrogen-vacancy center spins near 1000 kelvin. Nat. Commun. 10, 1344 (2019).

Pelliccione, M. et al. Scanned probe imaging of nanoscale magnetism at cryogenic temperatures with a single-spin quantum sensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 700–705 (2016).

Childress, L. & Hanson, R. Diamond NV centers for quantum computing and quantum networks. MRS Bull. 38, 134 (2013).

Andrich, P. et al. Long-range spin wave mediated control of defect qubits in nanodiamonds. npj Quantum Inf. 3, 28 (2017).

Kikuchi, D. et al. Long-distance excitation of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond via surface spin waves. Appl. Phys. Express 10, 103004 (2017).

Grinolds, M. S. et al. Subnanometre resolution in three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of individual dark spins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 279–284 (2014).

Hensen, B. et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 526, 682–686 (2015).

Fuchs, G. D., Dobrovitski, V. V., Toyli, D. M., Heremans, F. J. & Awschalom, D. D. Gigahertz dynamics of a strongly driven single quantum spin. Science 326, 1520–1522 (2009).

Jarmola, A., Acosta, V. M., Jensen, K., Chemerisov, S. & Budker, D. Temperature- and magnetic-field-dependent longitudinal spin relaxation in nitrogen-vacancy ensembles in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 197601 (2012).

Barfuss, A., Teissier, J., Neu, E., Nunnenkamp, A. & Maletinsky, P. Strong mechanical driving of a single electron spin. Nat. Phys. 11, 820–824 (2015).

MacQuarrie, E. R., Gosavi, T. A., Jungwirth, N. R., Bhave, S. A. & Fuchs, G. D. Mechanical spin control of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 227602 (2013).

Ovartchaiyapong, P., Lee, K. W., Myers, B. A. & Jayich, A. C. B. Dynamic strain-mediated coupling of a single diamond spin to a mechanical resonator. Nat. Commun. 5, 4429 (2014).

Labanowski, D. et al. Voltage-driven, local, and efficient excitation of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat6574 (2018).

Liu, L., Moriyama, T., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011).

Hamadeh, A. et al. Full control of the spin-wave damping in a magnetic insulator using spin-orbit torque. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 197203 (2014).

Solyom, A. et al. Probing a spin transfer controlled magnetic nanowire with a single nitrogen-vacancy spin in bulk diamond. Nano Lett. 18, 6494–6499 (2018).

Burek, M. J. et al. M. Free-standing mechanical and photonic nanostructures in single-crystal diamond. Nano Lett. 12, 6084–6089 (2012).

Lee-Wong, E. et al. Nanoscale detection of magnon excitations with variable wavevectors through a quantum spin sensor. Nano Lett. 20, 3284–3290 (2020).

Wolfe, C. S. et al. Off-resonant manipulation of spins in diamond via precessing magnetization of a proximal ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 89, 180406 (2014).

Du, C. H. et al. Control and local measurement of the spin chemical potential in a magnetic insulator. Science 357, 195–198 (2017).

Jelezko, F., Gaebel, T., Popa, I., Gruber, A. & Wrachtrup, J. Observation of coherent oscillations in a single electron spin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 076401 (2004).

Taminiau, T. H., Cramer, J., van der Sar, T., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal control and error correction in multi-qubit spin registers in diamond. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 171–176 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of Tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

An, T. et al. Unidirectional spin-wave heat conveyer. Nat. Mater. 12, 549–553 (2013).

Qin, H., Hämäläinen, S. J., Arjas, K., Witteveen, J. & van Dijken, S. Propagating spin waves in nanometer-thick yttrium iron garnet films: dependence on wave vector, magnetic field strength, and angle. Phys. Rev. B 98, 224422 (2018).

Mühlherr, C., Shkolnikov, V. O. & Burkard, G. Magnetic resonance in defect spins mediated by spin waves. Phys. Rev. B 99, 195413 (2019).

Yu, H. et al. Magnetic thin-film insulator with ultra-low spin wave damping for coherent nanomagnonics. Sci. Rep. 4, 6848 (2014).

Li, Y. & Bailey, W. E. Wave-number-dependent Gilbert damping in metallic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 117602 (2016).

Safranski, C. et al. Spin caloritronic nano-oscillator. Nat. Commun. 8, 117 (2017).

De Lange, G., Wang, Z. H., Ristè, D., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Universal dynamical decoupling of a single solid-state spin from a spin bath. Science 330, 60–63 (2010).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Trifunovic, L., Pedrocchi, F. L. & Loss, D. Long-distance entanglement of spin qubits via ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. X 3, 041023 (2014).

Sun, Y. et al. Damping in yttrium iron garnet nanoscale films capped by platinum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 106601 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Francesco Casola for fabricating the diamond nanobeams and Feiyang Ye for helpful discussions. C.R.D. acknowledges the support from the U.S. National Science Foundation under award ECCS-2029558 and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award FA9550-20-1-0319. Y.X., H.W., and E.E.F. were supported by Quantum-Materials for Energy Efficient Neuromorphic-Computing, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by DOE, Office of Science, BES under Award NO. DE-SC0019273. C.L. and M.W. were supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (EFMA-1641989 and ECCS-1915849).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.D. conceived the idea and designed the project. X.W. performed the measurements. E.L-W. and N.M. built the confocal setup. X.Y., H.L.W., and E.E.F. fabricated the devices. C.L. and M.W. provided the YIG samples. H.F.W. contributed to the COMSOL Multiphysics simulations. H.L.W. and C.R.D. wrote the paper with the help from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Xiao, Y., Liu, C. et al. Electrical control of coherent spin rotation of a single-spin qubit. npj Quantum Inf 6, 78 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-00308-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-00308-8

This article is cited by

-

Off-resonant detection of domain wall oscillations using deterministically placed nanodiamonds

npj Spintronics (2023)

-

Quantum control of spin qubits using nanomagnets

Communications Physics (2022)