Abstract

The efficient and reliable verification of quantum states plays a crucial role in various quantum information processing tasks. We consider the task of verifying entangled states using one-way and two-way classical communication and completely characterize the optimal strategies via convex optimization. We solve these optimization problems using both analytical and numerical methods, and the optimal strategies can be constructed for any bipartite pure state. Compared with the nonadaptive approach, our adaptive strategies significantly improve the efficiency of quantum state verification. Moreover, these strategies are experimentally feasible, as only few local projective measurements are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A basic yet important step in most quantum information processing tasks is to efficiently and reliably characterize a quantum state. The standard approach is to perform quantum state tomography by fully reconstructing the density matrix.1 However, tomography is known to be both time consuming and computationally hard due to the exponentially increasing number of parameters to be reconstructed;2,3 moreover, the underlying approximations may be conceptually problematic.4 In fact, full tomographic information is often not required, and a lot of effort has been devoted to characterizing quantum states with non-tomographic methods.5,6,7,8 Recently, an alternative statistical approach, namely quantum state verification, has triggered much research interest due to its powerful efficacy.9,10,11,12,13

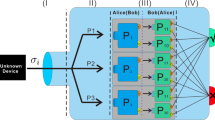

Quantum state verification is a procedure for gaining confidence that the output of some quantum device is a particular state by employing local measurements.9 Consider a device that is supposed to produce the target state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\), but may in practice produce \({\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2},\ldots ,{\sigma }_{N}\) in \(N\) runs. In the ideal scenario, the verifier has the promise that either \({\sigma }_{k}=\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|\) for all \(k\) or that \({\sigma }_{k}\) have a finite distance to \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\), i.e., \(\left\langle \psi \right|{\sigma }_{k}\left|\psi \right\rangle \le 1-\varepsilon\) for all \(k\). Given access to some set of allowed measurements, the verifier must certify that the source prepares \(\left|\psi \right\rangle .\) One cannot exclude that he certifies the source to be correct although it is not, but this failure probability \(\delta\) should be as small as possible.

In general, for each state \({\sigma }_{k}\) the verifier may apply a different measurement with some predefined probability. So a state verification strategy can be expressed as \(\Omega ={\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{p}_{i}{\Omega }_{i}\), where \(({p}_{1},{p}_{2},\ldots ,{p}_{n})\) is a probability distribution, and \(\{{\Omega }_{i},{\mathbb{1}}-{\Omega }_{i}\}\) are allowed measurements with outcomes labeled by “pass” and “fail”, respectively. For each output state \({\sigma }_{k}\), the verifier randomly chooses a measurement \(\{{\Omega }_{i},{\mathbb{1}}-{\Omega }_{i}\}\) with probability \({p}_{i}\), then performs the test. In a pass instance, the verifier continues to state \({\sigma }_{k+1}\), otherwise the verification ends and the verifier concludes that the state was not \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\). To guarantee that the perfect state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is never rejected we assume \({\Omega }_{i}\) satisfies \(\left\langle \psi \right|{\Omega }_{i}\left|\psi \right\rangle =1\); it has been observed in ref. 9 that such strategies are better than others. The worst-case failure probability of each run is given by \({\max }_{\left\langle \psi \right|\sigma \left|\psi \right\rangle \le 1-\varepsilon } {\mathrm {{Tr}}}(\Omega \sigma )=1-\varepsilon v(\Omega )\), where \(v(\Omega )\) represents the spectral gap between the largest and the second largest eigenvalues of \(\Omega\).9

In the case that all \(N\) states pass the test, we achieve the confidence \(1-\delta\) with

In reality, however, quantum devices are never perfect, so the verifier cannot be promised that either \({\sigma }_{k}=\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|\) or \(\left\langle \psi \right|{\sigma }_{k}\left|\psi \right\rangle \le 1-\varepsilon\) for all \(k\). Instead, a more practical task is to certify with high confidence that the fidelity of the output state is larger than a threshold value \(1-\varepsilon\). In this case, the verifier measures the frequency \(f\) of the pass instances. If \(f\,>\,1-\varepsilon v(\Omega )\), the confidence \(1-\delta\) can be derived from the Chernoff bound14,15

where \(D(x\parallel y)=x{\log}(\frac{x}{y})+(1-x){\log}(\frac{1-x}{1-y})\) is the Kullback–Leibler divergence.

The advantage of the state verification approach is that the failure probability \(\delta\) decreases exponentially with \(N\), hence the target state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) can be potentially verified using only few copies of the state. As seen from Eqs. (1) and (2), the performance of a verification strategy depends solely on \(v(\Omega )\). Therefore, to achieve an optimal strategy, we need to maximize \(v(\Omega )\) over all accessible measurements. Although lots of effort has been devoted to this research line, few optimal strategies have been found. To the best of our knowledge, the only optimal strategy reported by now is the verification of two-qubit pure states with local projective measurements (PMs).9

In this work, we introduce adaptive measurements, i.e., measurements assisted by local operations and classical communication (LOCC)16,17 to the task of quantum state verification. We show that the efficiency of the verification can be significantly improved by considering adaptive measurements. For any \({d}_{1}\times {d}_{2}\) bipartite pure state, we explicitly construct the optimal one-way, as well as near-optimal two-way adaptive verification strategies. Best of all, in these strategies, only few local PMs are needed for their implementation in the laboratory.

Results

Optimal state verification as convex optimization

In the following, we derive two convex optimization problems that completely characterize the optimal adaptive state verification strategies assisted by one-way and one-round two-way classical communication, respectively. In general, to get an optimal verification strategy, we need to consider the optimization problem

where \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is the target state we want to verify, and \({\mathcal{M}}\) denotes the set of all allowed measurements. Be reminded that \(v(\Omega )\) represents the spectral gap between the largest and the second largest eigenvalues of \(\Omega\). As \({\Omega }_{i}\le {\mathbb{1}}\), the last constraint leads to \({\Omega }_{i}\left|\psi \right\rangle =\left|\psi \right\rangle\) and \({P}^{\perp }{\Omega }_{i}{P}^{\perp }={\Omega }_{i}-\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|\), where \({P}^{\perp }={\mathbb{1}}-\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|\). Hence, \(v(\Omega )\) admits an alternative expression

where \(\left|| \ \cdot \ \right||\) denotes the largest eigenvalue.

Generally speaking, the optimization in Eq. (3) is difficult to solve, if not impossible at all, because the set of all possible measurements cannot be easily characterized. Here, we give a complete characterization of \(\Omega\) for both one-way and one-round two-way adaptive measurements, then reduce the corresponding problems to convex optimization. These optimization problems can be further simplified and solved. For succinctness, hereafter we restrict the two-way adaptive measurements to one-round communication only. In addition, the accessible measurements allowed in our verification strategies are not restricted to PMs, i.e., positive operator-valued measures (POVMs) are possible, although in the end we show that the optimal strategies can be achieved with PMs in most cases.

Without loss of generality, a bipartite pure state can be written as \(\left|\psi \right\rangle ={\sum }_{i=1}^{d}{\lambda }_{i}\left|ii\right\rangle\), where the Schmidt coefficients satisfy \({\lambda }_{1}\ge {\lambda }_{2}\ge \ldots {\lambda }_{d}\,\,>\,\,0\) and \({\sum }_{i=1}^{d}{\lambda }_{i}^{2}=1\).18

We start with the analysis of one-way communication. In this case, Alice first performs a measurement, and sends the measurement outcome to Bob. Bob then chooses his measurement in accordance with Alice’s measurement outcome. Hence, the one-way adaptive strategy \({\Omega }^{\to }\) takes the form

where \({\{{M}_{a| i}\}}_{a}\) are measurements on Alice’s system, and each \(\{{N}_{a| i},{\mathbb{1}}-{N}_{a| i}\}\) is a “pass” or “fail” measurement on Bob’s system depending on Alice’s measurement outcome. Here, we can assume that the \({M}_{a| i}\) are rank-one, otherwise some further decomposition can make this assumption satisfied. If the joint system is in state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\), Bob’s subsystem would collapse to some pure state \({P}_{a| i}={\mathrm {{Tr}}}_{\mathrm {{A}}}({M}_{a| i}\otimes {\mathbb{1}}\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|)/{\mathrm {Tr}}({M}_{a| i}\otimes {\mathbb{1}}\left|\psi \right\rangle \left\langle \psi \right|)\) after Alice’s measurement \({\{{M}_{a| i}\}}_{a}\). Then the best strategy for Bob is to perform the measurement \(\{{P}_{a| i},{\mathbb{1}}-{P}_{a| i}\}\) to verify whether his subsystem is in state \({P}_{a| i}\). Mathematically, to ensure that \(\left\langle \psi \right|{\Omega }_{i}^{\to }\left|\psi \right\rangle =1\), \({N}_{a| i}\) must satisfy that \({N}_{a| i}\ge {P}_{a| i}\). If all \({N}_{a| i}\) satisfy \({N}_{a| i}={P}_{a| i}\), we call the one-way adaptive strategy \({\Omega }^{\to }\) semi-optimal. Hence, to maximize \(v({\Omega }^{\to })\), i.e., to minimize \(\left|| {\sum }_{i}{p}_{i}{P}^{\perp }{\Omega }_{i}^{\to }{P}^{\perp }\right||\), we can restrict \({\Omega }^{\to }\) to be semi-optimal strategies.

From the definition, we get the following necessary conditions for \({\Omega }^{\to }\) being semi-optimal

where \({\mathcal{S}}\) is the set of separable operators, i.e., unnormalized separable states.17 Next, we show that these constraints are also sufficient. \({\Omega }^{\to }\) is separable implies that there exists a decomposition \({\Omega }^{\to }={\sum }_{a}{M}_{a}\otimes {N}_{a}\), such that \({M}_{a}\) are positive semidefinite and \({N}_{a}\) are rank-one projectors. Then, \({\mathrm {{Tr}}}_{\mathrm {{B}}}({\Omega }^{\to })={\mathbb{1}}\) implies \({\sum }_{a}{M}_{a}={\mathbb{1}}\), i.e., \({\{{M}_{a}\}}_{a}\) is a measurement on Alice’s system. This concludes our proof by taking into account the last constraint. Thus, the optimization in Eq. (3) can be written as

for one-way adaptive verification strategies.

We move on to discuss the one-round two-way communication scenario. In this case, Alice and Bob use shared randomness to decide who performs the measurement first. After the measurement, he/she sends the measurement outcome to the other party. Then the receiver chooses her/his measurement according to the received measurement outcome. Thanks to the permutation symmetry of \(\left|\psi \right\rangle ={\sum }_{i=1}^{d}{\lambda }_{i}\left|ii\right\rangle\), the optimization in this setting can be easily simplified. Let \(S\) be the SWAP operator, i.e., \(S\left|i\right\rangle \left|j\right\rangle =\left|j\right\rangle \left|i\right\rangle\) for all \(i,j=1,2,\ldots ,d\), then we have \(S\left|\psi \right\rangle =\left|\psi \right\rangle\). This indicates that, for two-way adaptive measurements, if \(\Omega\) satisfies the constraints in Eq. (3), so does \(\frac{1}{2}(\Omega +S\Omega {S}^{\dagger })\). Furthermore, Eq. (4) implies

Hence, we can focus on the two-way adaptive strategies \({\Omega }^{\leftrightarrow }\) that are invariant under the SWAP operation, i.e., \({\Omega }^{\leftrightarrow }=\frac{1}{2}({\Omega }^{\to }+{\Omega }^{\leftarrow })\), where \({\Omega }^{\to }\) is a one-way adaptive strategy and \({\Omega }^{\leftarrow }=S{\Omega }^{\to }{S}^{\dagger }\). Similarly, to optimize \(v({\Omega }^{\leftrightarrow })\), we can also restrict \({\Omega }^{\to }\) to be semi-optimal. Thus, the optimization in Eq. (3) can be written as

for two-way adaptive verification strategies.

Optimal verification of two-qubit states

Without loss of generality, we write the two-qubit entangled pure state as \(\left|\psi \right\rangle =\cos \theta \left|00\right\rangle +\sin \theta \left|11\right\rangle\) with \(0\, < \,\theta \le \pi /4\). Then the subspace \({P}^{\perp }\) is spanned by \({\{\left|{\psi }_{i}\right\rangle \}}_{i=1}^{3}:= \{\left|01\right\rangle ,\left|10\right\rangle ,\sin \theta \left|00\right\rangle -\cos \theta \left|11\right\rangle \}\).

First, we need a group \(G\) to simplify the optimizations. The group \(G\) is defined to be generated by the unitary operator \(g=\Phi \otimes {\Phi }^{\dagger }\), where \(\Phi\) is the phase gate, i.e., \(\Phi \left|0\right\rangle =\left|0\right\rangle\) and \(\Phi \left|1\right\rangle ={\rm{i}}\left|1\right\rangle\). Then we can show

for some \({w}_{i}\); see Supplementary Note A for the proof. As \(g\left|\psi \right\rangle =\left|\psi \right\rangle\), \(\tilde{\Omega }\) also satisfies the constraints in Eqs. (7) and (9) if \(\Omega\) does. Furthermore, Eq. (4) implies

Thus, we can restrict to the diagonal \({\Omega }^{\to }\) as in Eq. (10) for the optimizations in Eqs. (7) and (9).

Then, we consider the case of one-way adaptive verification. For two-qubit quantum states, the positive partial transpose (PPT) criterion is necessary and sufficient to characterize their separability.19,20 Thus, by combining Eq. (10) with the PPT criterion, the optimization in Eq. (7) can be written as

where the constraints arise only from \({\Omega }^{\to }\ge 0\) and \({\mathrm {{Tr}}}_{\mathrm{{B}}}({\Omega }^{\to })={\mathbb{1}}\), since the PPT criterion gives the redundant condition \({w}_{1}{w}_{2}\ge {\sin }^{2}\theta {\cos }^{2}\theta {(1-{w}_{3})}^{2}\). As \(0\,<\,\theta \,\le\, \pi /4\), we have \({w}_{2}\ge {w}_{1}\). Thus, the solution of Eq. (12) is attained when \({w}_{2}={w}_{3}\), and

In general, the measurements associated with the optimal solution are POVMs. However, one can directly calculate that the bound in Eq. (13) can be achieved already with PMs

where

with \(\left|{\varphi }_{0}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left|0\right\rangle +\left|1\right\rangle )\otimes (\cos \theta \left|0\right\rangle +\sin \theta \left|1\right\rangle )\) and \(\left|{\varphi }_{k}\right\rangle ={g}^{k}\left|{\varphi }_{0}\right\rangle\).

Next, we discuss the case of two-way adaptive verification. By combining Eq. (10) and the PPT criterion, we can get a simplification of the optimization in Eq. (9) by simply replacing the objective function in Eq. (12) with

whose solution is given by

Again, we explicitly write down the PMs

where \({P}_{ZZ}^{+}\), \({X}_{\psi }^{\to }\), and \({Y}_{\psi }^{\to }\) are defined as in Eq. (15), and \({X}_{\psi }^{\leftarrow }=S{X}_{\psi }^{\to }{S}^{\dagger }\) and \({Y}_{\psi }^{\leftarrow }=S{Y}_{\psi }^{\to }{S}^{\dagger }\).

Finally, we compare the adaptive strategies with the nonadaptive approach in ref. 9. For two-qubit entangled states, we plot the optimal values of \(v(\Omega )\) for different strategies in Fig. 1. As can be seen, the two-way strategy works much better than the one-way strategy, whereas both the adaptive strategies significantly outperform the nonadaptive one. Concerning the resources used in each strategy, we have the following remarks. Although no classical communication is involved in the measurement process of the nonadaptive strategy, it is still a necessary resource for the data processing after the measurement. On the contrary, the one-way adaptive strategy relies on classical communication for the measurements, but no classical communication is needed for the data processing as one party alone can determine whether the result is a pass or fail instance. The case for the two-way adaptive strategy is similar, but to obtain the final frequency of the pass instances, the two parties need to cooperate.

Optimal verification of general bipartite states

We move on to discuss the optimal adaptive verification of general bipartite states. Firstly, we need a larger group \(G\) for the general bipartite (two-qudit) pure state \(\left|\psi \right\rangle ={\sum }_{i=1}^{d}{\lambda }_{i}\left|ii\right\rangle\), where the Schmidt coefficients satisfy \({\lambda }_{1}\ge {\lambda }_{2}\ge \ldots {\lambda }_{d}>0\) and \({\sum }_{i=1}^{d}{\lambda }_{i}^{2}=1\). The group \(G\) is defined to be generated by the unitary operators \(\{{g}_{k}={\Phi }_{k}\otimes {\Phi }_{k}^{\dagger },\,k=1,2,\ldots ,d\}\), where \({\Phi }_{k}\left|j\right\rangle ={\rm{i}}\left|j\right\rangle\) when \(j=k\), and \({\Phi }_{k}\left|j\right\rangle =\left|j\right\rangle\) otherwise. Then we can show

for some \({w}_{ij}\) and \({\rho }_{ij}\), where \(\left|G\right|\) is the order of \(G\); see Supplementary Note A for the proof. Similar to the two-qubit case, if \(\Omega\) satisfies the constraints in Eqs. (7) and (9), so does \(\tilde{\Omega }\), since \(g\left|\psi \right\rangle =\left|\psi \right\rangle\) for all \(g\in G\). Furthermore, Eq. (4) implies

Hence, we can restrict \({\Omega }^{\to }\) to be of the form in Eq. (19) for the optimizations in Eqs. (7) and (9). Additionally, \(\left\langle \psi \right|\Omega \left|\psi \right\rangle =1\), i.e., \(\Omega \left|\psi \right\rangle =\left|\psi \right\rangle\), means \(\rho {\boldsymbol{\lambda }}={\boldsymbol{\lambda }}\), where \(\rho := {({\rho }_{ij})}_{i,j=1}^{d}\) is Hermitian, and \({\boldsymbol{\lambda }}={({\lambda }_{1},{\lambda }_{2},\ldots ,{\lambda }_{d})}^{\mathrm {{T}}}\).

Secondly, we consider the case of one-way adaptive verification with the help of the group \(G\). The main difference between two-qudit and two-qubit states is that the PPT criterion is only necessary but not sufficient to characterize the separability for \(d\ge 3\).20 Hence, by replacing \({\Omega }^{\to }\in {\mathcal{S}}\) with \({({\Omega }^{\to })}^{{T}_{B}}\ge 0\), Eqs. (7) and (19) only give us a relaxation of the original optimization

where the constraints arise from \(0\le {\Omega }^{\to }\le {\mathbb{1}}\), the PPT criterion, \({\mathrm {{Tr}}}_{\mathrm{B}}({\Omega }^{\to })={\mathbb{1}}\), and \(\left\langle \psi \right|{\Omega }^{\to }\left|\psi \right\rangle =1\) respectively. Therefore, the solution of this relaxed problem sets an upper bound of the optimal \(v({\Omega }^{\to })\). To show that the solution is a valid strategy, we still need to prove that the optimal \({\Omega }^{\to }\) obtained from Eq. (21) is separable. Here, instead of resorting to numerical methods, we can analytically solve the optimization in Eq. (21), which gives

for all \(d\ge 2\). Moreover, the bound in Eq. (22) can be achieved with PMs

where

with \({\gamma }_{d}={{\rm{e}}}^{\frac{2\pi {\rm{i}}}{d}}\) and \(w={\lambda }_{1}^{2}/(1+{\lambda }_{1}^{2})\); see Supplementary Note B for more details. In passing, we note two special cases of Eq. (24). When \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is separable, i.e., \(d=1\), Eq. (24) gives the optimal nonadaptive strategy with \(v(\Omega )=1\). When \(\left|\psi \right\rangle\) is maximally entangled, \({\{\left|{\phi }_{k}\right\rangle \}}_{k=1}^{d}\) forms an orthogonal basis. Hence, Eq. (24) gives the optimal nonadaptive strategy.9,21

In practice, the above strategy can be easily implemented. Alice first randomly chooses one of the two measurements \({\{\left|k\right\rangle \}}_{k=1}^{d}\) and \({\{\left|{f}_{k}\right\rangle \}}_{k=1}^{d}\) with probabilities \(w\) and \(1-w\), respectively. The former measurement can be performed directly, while the latter one requires some random phase shifts from \(G\) in advance. Then Alice sends all the information to Bob via classical communication, upon receiving which Bob can proceed to perform the corresponding test.

Lastly, we consider the case of two-way adaptive verification. By the same token, the efficiency can be improved by averaging \({\Omega }^{\to }\) and its swap \({\Omega }^{\leftarrow }\). Specifically, we can get

when \({\Omega }^{\to }\) is of the form in Eq. (23) with \(w={\lambda }^{2}/(1+{\lambda }^{2})\) and \({\lambda }^{2}=\frac{1}{2}({\lambda }_{1}^{2}+{\lambda }_{2}^{2})\). However, unlike the two-qubit case, this strategy is only near-optimal for general bipartite states. To get the optimal strategy, we can numerically solve the optimization in Eq. (25), then explicitly decompose the obtained strategy with the method in ref. 22. Our testing results show that the optimal strategy is at most \(4 \%\) better in efficiency than the near-optimal strategy for all \(d\le 10\), whereas the measurement settings of the optimal strategies may involve complicated POVMs; instead the near-optimal strategies in Eq. (25) only involve PMs; see Supplementary Note C for more details.

Before concluding, two remarks are in order. First, Eqs. (22) and (25) imply that \(v(\Omega )\ge 1/2\) for all of our adaptive strategies. This implies that \(N\,\lesssim\, 2{\varepsilon }^{-1}\,{\log}\,{\delta }^{-1}\) copies of states are enough for verifying any bipartite states, which is independent of the dimension \(d\). This is of the same scale with the best global strategies with entangled measurements, which need \(N\approx {\varepsilon }^{-1}\,{\log}\,{\delta }^{-1}\) copies.9 On the contrary, the best nonadaptive strategies known so far need \(N\,\gtrsim \,d{\varepsilon }^{-1}\,{\log}\,{\delta }^{-1}\) to verify a generic two-qudit state for \(d\ge 3\),23 which is worse than our adaptive strategies by an order \(O(d)\). Second, it is possible to further improve the efficiency of the adaptive strategies by involving many-round communication. However, these strategies require coherence-preserving measurements and can only improve the efficiency up to a constant factor \(c\) with \(c\le 2\) for all dimensions.

Discussion

Quantum state verification is an efficient and reliable method for gaining confidence about the quality of quantum devices, which is a crucial step in almost all quantum information-processing tasks and foundational studies. In this work, we integrated adaptive measurements to the problem of state verification and formulated two convex optimization problems that completely characterize the optimal adaptive strategies for one-way and one-round two-way classical communication. We solve these optimization problems using both analytical and numerical methods, and the optimal or near-optimal strategies are constructed explicitly for any bipartite pure state. As a demonstration, we compared the optimal adaptive strategies with the nonadaptive one, and find that the verification efficiency can be significantly improved if classical communication is allowed. Finally, our adaptive verification strategies are readily applicable in experiments as only few local PMs are involved. For future research, it is very interesting to consider the multipartite case, which is more relevant for applications. Moreover, it is meaningful to discuss how the present approach needs to be modified, if the measurement devices are not perfectly characterized. Statistical tools developed for quantum state discrimination24,25 may be helpful for this purpose.

Note added. During the preparation of the manuscript we became aware of related works by Wang and Hayashi26 and Li et al.27

Data availability

The data that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The codes that support the results of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Paris, M. & Řeháček, J. (eds) Quantum State Estimation, Vol. 649 of Lecture Notes in Physics (Springer, Heidelberg, 2004).

Häffner, H. et al. Scalable multiparticle entanglement of trapped ions. Nature 438, 643–646 (2005).

Shang, J., Zhang, Z. & Ng, H. K. Superfast maximum-likelihood reconstruction for quantum tomography. Phys. Rev. A. 95, 062336 (2017).

Schwemmer, C. et al. Systematic errors in current quantum state tomography tools. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 080403 (2015).

Tóth, G. & Gühne, O. Detecting genuine multipartite entanglement with two local measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 060501 (2005).

Gross, D., Liu, Y.-K., Flammia, S. T., Becker, S. & Eisert, J. Quantum state tomography via compressed sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 150401 (2010).

Flammia, S. T. & Liu, Y.-K. Direct fidelity estimation from few Pauli measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 230501 (2011).

daSilva, M. P., Landon-Cardinal, O. & Poulin, D. Practical characterization of quantum devices without tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 210404 (2011).

Pallister, S., Linden, N. & Montanaro, A. Optimal verification of entangled states with local measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 170502 (2018).

Dimić, A. & Dakić, B. Single-copy entanglement detection. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 11 (2018).

Morimae, T., Takeuchi, Y. & Hayashi, M. Verification of hypergraph states. Phys. Rev. A. 96, 062321 (2017).

Takeuchi, Y. & Morimae, T. Verification of many-qubit states. Phys. Rev. X. 8, 021060 (2018).

Zhu, H. & Hayashi, M. Efficient verification of hypergraph states. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054047 (2019).

Chernoff, H. A measure of asymptotic efficiency for tests of a hypothesis based on the sum of observations. Ann. Math. Statist. 23, 493–507 (1952).

Hoeffding, W. Probability inequalities for sums of bounded random variables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 13–30 (1963).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Purification of noisy entanglement and faithful teleportation via noisy channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 722–725 (1996).

Watrous, J. The Theory of Quantum Information. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2018).

Peres, A. Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods. (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002).

Peres, A. Separability criterion for density matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1413–1415 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states: necessary and sufficient conditions. Phys. Lett. A. 223, 1–8 (1996).

Zhu, H. & Hayashi, M. Optimal verification and fidelity estimation of maximally entangled states. Phys. Rev. A. 99, 052346 (2019).

Shang, J. & Gühne, O. Convex optimization over classes of multiparticle entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 050506 (2018).

Liu, Y.-C., Yu, X.-D., Shang, J., Zhu, H. & Zhang, X. Efficient verification of Dicke states. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 044020 (2019).

Barnett, S. M. & Croke, S. Quantum state discrimination. Adv. Opt. Photonics 1, 238–278 (2009).

Bae, J. & Kwek, L.-C. Quantum state discrimination and its applications. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 48, 083001 (2015).

Wang, K. & Hayashi, M. Optimal verification of two-qubit pure states. Phys. Rev. A. 100, 032315 (2019).

Li, Z., Han, Y.-G. & Zhu, H. Efficient verification of bipartite pure states. Phys. Rev. A. 100, 032316 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mariami Gachechiladze and Chau Nguyen for discussions. This work was supported by the DFG and the ERC (Consolidator Grant 683107/TempoQ). X.-D.Y. acknowledges funding from a CSC-DAAD scholarship. J.S. acknowledges support by the Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars and the National Natural Science Foundation of China through Grant No. 11805010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-D.Y. and J.S. did the theoretical analysis and performed the numerical simulations. O.G. supervised the project. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, XD., Shang, J. & Gühne, O. Optimal verification of general bipartite pure states. npj Quantum Inf 5, 112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0226-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0226-z

This article is cited by

-

Robust and efficient verification of graph states in blind measurement-based quantum computation

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Optimizing measurements sequences for quantum state verification

Quantum Information Processing (2023)

-

Optimal verification of the Bell state and Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger states in untrusted quantum networks

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Classical communication enhanced quantum state verification

npj Quantum Information (2020)

-

Towards the standardization of quantum state verification using optimal strategies

npj Quantum Information (2020)