Abstract

Entangling gates with error rates reaching the threshold for quantum error correction have been reported for CZ gates using adiabatic longitudinal control based on the interaction between the |11〉 and |20〉 states. Here, we design and implement nonadiabatic CZ gates, which outperform adiabatic gates in terms of speed and fidelity, with gate times reaching \(1.25/(2\sqrt 2 g_{01,10})\), and fidelities reaching 99.54 ± 0.08%. Nonadiabatic gates are found to have proportionally less incoherent error than adiabatic gates thanks to their fast gate times, which leave more room for further improvements in the design of the control pules to eliminate coherent errors. We also show that state leakage can be reduced to below 0.2% with optimisation. Furthermore, the gate optimisation process is highly feasible: experimental optimisation can be expected to take less than four hours. Finally, the gate design process can be extended to CCZ gates, and our preliminary results suggest that this process would be feasible as well, if we can measure the CCZ fidelity separate from the initialisation and readout errors in experimental optimisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivated by the quest for quantum error correction and expanding the set of realisable circuits,1,2 there has been a great effort to improve the design of entangling gates,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and by now there is a rich array of design choices in a variety of quantum computing modalities, including superconducting quantum circuits,12 trapped ions,13 quantum dots14 and NV diamonds.15,16 Notable designs for entangling gates in superconducting circuits, include fast adiabatic gates,17 frequency modulation,11,18 cross resonance19,20 and resonator-induced phase,21,22 which effect the gates using longitudinal (first two) or transverse (last two) control of the qubits. Currently, the best results for entangling-gate fidelity using longitudinal control is 99.44%,3 and using transverse control is 99.1%.20 The former result reaches the surface code threshold error rate.3,23

Precision control of qubit states is hindered by coherent and incoherent errors. Coherent errors, comprised of phase errors and leakage errors, can be eliminated in principle by improving the gate design and by calibration of nonideal factors such as cross-talk, pulse distortion, energy drift and readout drift. Incoherent errors, on the other hand, can not normally be eliminated within the domain of designing and calibrating pulses, and the best, most direct way to mitigate this source of error is to make the gate as fast as possible. The information loss due to decoherence during the gate time thus sets an upper limit on the achievable fidelity of the operation.

The highest gate fidelities reported to date use fast adiabatic gates.3 The principle of the fast adiabatic design is to change the frequency of the qubits slowly enough that Landau–Zener transition probability is minimised. The speed of the gate is maximised, all while maintaining the population stability provided by the adiabatic theorem. Barends et al. provide an analysis of the sources of coherent and incoherent errors in these gates, and conclude that 55% of the error comes from decoherence. The other errors are reported to be from coherent sources: phase error (29%) and state leakage (21%).3 Our work aims to address the dominant source of error, and improve on this leading gate design. We design and implement nonadiabatic gates and show that this design can achieve performance parity with the reported fidelities of adiabatic gates. Normalised by the coupling strength Ts = 1/(2g11,20), our gates are significantly faster than their adiabatic counterparts, reaching 1.25Ts (40 ns), compared to adiabatic gate times, which range from 1.66 to 1.87Ts.3 The faster gate times mean the upper bound set by decoherence during the operation is higher, which leaves more room for improvement of overall gate fidelity by focusing on coherent errors. Our analysis shows that approximately 48% of the error is incoherent. Our simulations also find that the fastest possible gate is 1.06Ts, but in practice, technical limitations will cause the gate time to increase.

Results

Simulation of nonadiabatic CZ gate

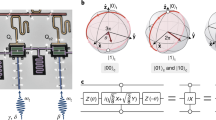

A CZ gate design we used in this experiment works by adjusting the frequency of the qubits so that the two-qubit state |11〉 interacts with the noncomputational state |20〉24 (Fig. 1a). In our case, we only tuned one the frequency of qubit a, without changing qubit b (Fig. 1b). The |11〉–|20〉 interaction will cause a phase difference of π relative to the three other two-qubit states, thus implementing a CZ gate. In the nonadiabatic case, the detuning from the energy eigenstate is made rapidly, making |E20 − E11|—the energy difference between the two interacting states—go to the order of g11,20. Once qubit a is rapidly detuned to the interaction point, the |11〉–|20〉 subspace of the two-qubit state processes around the Bloch sphere for one revolution (Fig. 1c), after which time the adjusted qubit is rapidly tuned back to its idle point. Analysis shows that when the pulse shown in Fig. 1b is applied, a large part of the population leaves the eigenstate before returning nearly in full (Fig. 1d). This is a distinguishing characteristic of nonadiabatic gates.

Nonadiabatic CZ gate design. a Principle of nonadiabatic CZ gate. |11〉 is moved rapidly to the interaction point and interacted with |20〉 for period of time and then moved back to the idle point. b Detuning pulse. The ideal, infinite-bandwidth pulse (green) moves instantaneously the interaction point. The realistic, 300 MHz-bandwidth pulse (red) has added edges on either side. The ideal (realistic) pulse takes 34 ns (40 ns) in theory. c Swap space. The green (red) circle shows the evolution resulting from the ideal (realistic) control pulse. The small green and red diamonds in x–z plane are the eigenstates during each of these evolutions. After the operation, the |11〉 has gained a phase of π relative to the other states. d State population in the eigenstate during the pulse. A large part of the population can be seen exiting and then re-entering the eigenstate

Ideally, the population of the |11〉 state instantly goes to the interaction point, gains the phase of π and returns instantly. But in practice, the bandwidth of the control pulses limits the speed of the detuning. To find a waveform that minimises population leakage to noncomputational states in the realistic situation where bandwidth is finite, we first search for a waveform without applying bandwidth restrictions, then take that result and restrict the waveform bandwidth. The waveform search is done with the conventional differential evolution (DE) optimisation method,25,26,27 using the simulated fidelity as the fitness function.

During the search, the waveform is parametrised by the total time of the operation and by relative weights of different frequencies that make up the pulse.28,29,30

Fidelity is defined as the normalised trace distance in the computational subspace between the desired unitary operation, and the one resulting from the simulated applied pulse.

Here, UCZ is the ideal operation, and UP is the evolution in the computational subspace caused by the detuning pulse.

Searching over the seven-parameter search space resulted in a parameters for W with a maximum fidelity of 99.97%. To adapt the ideal pulse to the experiment, we applied a 300 MHz Gaussian bandpass filter and added a 3 ns rising time and falling time for detuning. Doing so distorts the pulse, so the Nelder Mead (NM) algorithm31 was then used to maximise the fidelity of the modified waveform, reaching a final fidelity of 99.95%.

Theoretical analysis of the modified pulse shows that the theoretical finite-bandwidth waveform can reduce state leakage to 0.05% and phase error to 0.005 rad. The gate operation time is 1.06Ts for infinite bandwidth and 1.25Ts for 300 MHz bandwidth.

Experiment of nonadiabatic CZ gate

Our experiment uses two qubits from a 12-qubit superconducting quantum processor (Fig. 2a). The qubits32,33 are arranged in a linear array and are capacitively coupled to their neighbours, and the coupling strength is measured to be 11.0 MHz, corresponding Ts = 32.1 ns. Each qubit is also capacitively coupled to a readout resonator. Parameters for qubits used in the experiment are listed in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 2b.

Superconducting quantum processor. a Superconducting quantum circuit. Our qubits are capacitively coupled to their neighbours. Each qubit is capacitively coupled to an XY control line and a readout resonator, and inductively coupled to a Z control line. b Energy level at idle point and CZ swap point. Left shows energy levels without frequency tuning; right shows energy levels at the interaction point

Once the theoretical waveform for a CZ gate has been found in simulation, its actual fidelity is measured experimentally. First we measure and correct the dynamic single-qubit phase of two qubits using quantum process tomography34,35 (QPT). Once this is corrected, randomised benchmarking (RB) is used to optimise the fidelity of CZ gate by NM. To maximise error contrast during optimisation, we select the number of Clifford gate to be 15 and the interleaved gate to be CZ (Fig. 3a), then generate interleaved sequences to measure gate fidelity. We observe saturation of the NM optimisation algorithm in less than 120 evaluations (resulting pulse shown in Fig. 3b), which implies this scheme is efficient (Fig. 3c, d). The resulting fidelity of the CZ is 99.54 ± 0.08%, which is measured by interleaved RB and fitted by the formula shown in (Fig. 3e). The result is robust and stable for more than one week (see Discussion).

Nonadiabatic CZ optimisation. a Reference and interleaved sequence used for RB. The two-qubit Clifford gate C2,i is chosen randomly and C2,r is chosen such that all the gates together are equivalent to the identity. G is the gate we want to benchmark. b Control pulse applied to qubit 3 to realise nonadiabatic CZ gate after optimisation in experiment. Here, the CZ detuning pulse is given by f01,CZ(t) − f01,idle. c, d The convergence rate of waveform parameters and fidelity. e RB fitting result for nonadiabatic CZ gate. Here, A, pref, pint are obtained by the fit. \(d = 2^{N_{\rm{qubits}}}\), rref = (1 − pref)(d − 1)/d, rint = (1 − pint)(d − 1)/d

To reduce the effect of noise and maintain highly accurate pulses during the optimisation, we calibrate the readout and energy levels as the RB is taking place. Readout is calibrated by measuring the distribution of |0〉 and |1〉, while Ramsey measurements are used to determine the frequencies of each qubit. This data is collected and used to calibrate the measured state population in post processing and also to calibrate qubit frequencies by adjusting the DC current for the next NM evaluation. Including this calibration, the resulting optimised pulse takes around 2 h to calculate the RB pulse sequences and to allow for communication between the control hardware, and two more hours of on-chip operation.

Expanding to CCZ gate

Simulation

This scheme proves useful not only for CZ gates, but also achieves good results optimising CCZ gates.27,36 By applying a control pulse on qubit 3, the |111〉, |021〉, |030〉 populations will go to the interaction point where they can mutually exchange population nonadiabaticly (Fig. 4a–d). To expand the search space of waveform, we add third- and fourth-order Fourier components to Eq. (1), increasing the number of waveform parameters to 11. Including two parameters to select the frequencies of qubit 2 and 4, the total number of variables is 13. By applying such a pulse, |111〉 will get an added phase of (2n + 1)π, and |110〉 will get an added phase of 2nπ (n being an integer). The other six bases have almost no interaction, so they gain almost no extra phase. The DE algorithm is again used to optimise the CCZ waveform, obtaining a fidelity of 99.3% in simulation.

CCZ result. a–d for simulation and e for experiment. a Qubits energy level as a function of qubit 3 detuning. At around 160 MHz detuning of qubit 3, the |111〉, |021〉, and |030〉 states interact strongly (interaction point). b CCZ pulse applied to qubit 3, which obtains fidelity of 99.3%. c Evolution of each state under CCZ pulse. Dotted (solid) lines show the evolution when the initial state is |110〉 (|111〉). Both black lines (dotted and solid) hovering near unity for the entire pulse duration the means that pulse can be analysed by separating the evolution into two (nearly) independent subspaces. Note that |110〉 interacts strongly with |020〉, and that |111〉 interacts strongly with |021〉 and |030〉. |111〉 also interacts slightly with |120〉 in the |111〉-|021〉-|030〉-|120〉 subspace. d State population in the eigenstate during the pulse for |110〉 and |111〉 being input. e Process tomography of CCZ in experiment. The clear bars represent the ideal matrix and the solid bars represent the experimental matrix

Experiment

We used QPT to measure the fidelity of the CCZ gate for on-chip optimisation and the parameters for qubits are shown in Table 2. Using the simulation result as initial pulse and after about 50 NM evaluations, the CCZ fidelity was measured to be 93.3% (Fig. 4e) and the gate time was the same as simulation (78.5 ns). The discrepancy of fidelity between simulation and experiment is mainly caused by the initialisation and readout error, which limits the ability of the NM algorithm to converge accurately toward the optimal point.

Discussion

Our result demonstrates that the difficulties of nonadiabatic gates can be overcome to the point that gate fidelities exceed those of adiabatic gates reported in the literature, which themselves have already passed the threshold for quantum error correction using the surface code.

We notice that there has been much focus on adiabatic CZ gates, and there is theory developed to reduce the state population leakage throughout the entire pulse.17 But our work shows that as long as the population returns to the computational subspace by the end of the pulse, having population exit the eigenstate is acceptable. In practice, we find that state leakage is easily suppressed if the Z-pulse distortion calibration is performed well. Calibration and stabilisation of the qubits is therefore more worth considering.

Our experiment has proved that finding high-fidelity pulses is realistic and viable. We tried NM optimisation for different qubit frequencies and found that we were always able to reach fidelities of 99% in about 150 evaluations even in a noisy electromagnetic environment, which is comparable to adiabatic implementations.37 Continuing the investigation, we varied the energy level structure (frequency difference of two qubits, anharmonicity, and coupling strength) and searched for the theoretical detuning pulses. We found nonadiabatic CZ gates with fidelities higher than 99.9% and gate times lower than 1.1Ts after 50–200 evaluations of the NM algorithm. Due to the NM algorithm’s sensitivity to initial points, sometimes fidelities higher than 99.95% can not be obtained only using NM. However, using DE and NM together, we have always found fidelities high than 99.95% after 200 DE iterations which implies that a good practical nonadiabatic pulses exist and can be found with sufficiently sophisticated search techniques. The difference between experimental and theoretical fidelity is caused by the imperfect calibration of pulse distortion and the finite accuracy of practical control pulses.

We also investigated the robustness of CZ gate under control parameter fluctuations. We changed simulated waveform parameters by up to 1 MHz, and randomly adjusted each point on the resulting pulse according to a Gaussian distribution a with standard deviation of 1 MHz. The fidelity of the gate was found to never fall below 99.9%. Experimentally, the fidelity of interleaved sequences (m = 15, G = CZ) dropped from 68 to 65% after varying the waveform parameters in the same way. Also, the sequence fidelity (of the unaltered pulse) did not fall below 67% after one week. We conclude that high frequency noise and long time drift of control equipment do not significantly affect the CZ gates.

We expect nonadiabatic gates to be more effective in the future. Although it is very likely that superconducting qubits with coherence times exceeding hundreds of microseconds will be regularly fabricated soon, the decoherence error always contributes significantly to the total gate error. Our simulations show that the relationship between nonadiabatic CZ gate and decoherence time is given by rdecoherence = 0.38Tgate/T1,low + 0.62Tgate/T1,high + 0.45Tgate/Tφ,low + 0.93Tgate/Tφ,high, here, high (low) represents the qubit that involves (does not involve) the |2〉 state. According the decoherence time measured in experiment, the incoherent error and control error is 0.22% and 0.24%, respectively. The upper bound of |20〉 leakage error is 0.22% and could be lower if we could measure the |20〉 population directly. Control error is likely to be mitigated experimentally in the near term by taking the following steps: First, reduce and characterise the distortion of the waveform as it travels from the arbitrary waveform generators (AWG) to the qubits and do the corresponding calibration more accurately. Second, improve the voltage resolution and sampling resolution of the AWG. Lastly, design a more efficient search algorithm which includes resistance to noise, as well as find a different definition for the waveform parameters.38

Finding high quality control pulses and improving complex multi-qubits gates under experimental conditions remains challenging, as evidenced by continued research in this field.21,36 We believe that nonadiabatic detuning can be a powerful method21,26,27,36 for two- and three-qubits gates. The errors in the simulated gates are of the same order of magnitude as the errors from incoherent errors; additionally, the gate time is acceptably short (78.5 ns, 1.73/(2g01,10)). For these two reasons, our simulated pulses meet our experimental needs. However, as the initialisation and readout errors in QPT limit the experimental optimisation, it is essential to find a way to separate these errors and efficiently get the valid CCZ fidelity to further improve the CCZ gate.

Nonadiabatic CZ and CCZ gates can be extended into medium-scale quantum computation. The time that the system can stably work is two orders of magnitude longer than the time required for optimisation and the optimisation time can be significantly shortened by applying active reset technology.39 By setting qubits’ frequencies appropriately and designing tunable coupling strength qubits, we can realise the CZ (CCZ) gate in any adjacent two (three) qubits for quantum processors that contain hundreds of qubits or more. The CZ (CCZ) pulses only involve adjacent qubits and the nonadjacent CZ (CCZ) can be optimised parallel if the influence of cross-talk can be neglected. Hopefully nonadiabatic CZ (CCZ) gates in quantum processors with hundreds qubits can be completely optimised within an hour.

Methods

Hamiltonian and control pulse for CZ in simulation

The total system Hamiltonian is the sum of the static Hamiltonians, and each qubit is controlled independently by a tuning pulse. Qubits are modelled as three-level systems and qubit frequencies are 5.3 and 4.7 GHz, for qubit a and qubit b, respectively. Both qubits have an anharmonicity of 250 MHz. Their coupling strength g01,10/(2π) is 11 MHz.

The AWG we used has a sampling rate of 2 GHz. So, when simulating the evolution, we sample the continuous waveform W every 0.5 ns, and interpolate linearly between the sampled points to approximate the limitations of the hardware.

Differential Evolution

The DE algorithm used in CZ has a population size NP = 25, number of generations GEN = 200, differential weight F = 0.8, and crossover probability CR = 0.4. The lower and upper bounds of [tgate(ns); \(\vec x\)(GHz)] are [32; −0.36, −0.1, −0.1, −0.1, −0.1, −0.1, −0.1] and [38; −0.335, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1], respectively.

The DE algorithm used in CCZ has a population size NP = 50, number of generations GEN = 300, differential weight F = 0.8, and crossover probability CR = 0.4. The lower and upper bounds of [tgate(ns); \(\vec x\)(GHz); Δf01q2(GHz), Δf01q4(GHz)] are [30; 0, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, −0.2, 0.1, 0.1] and [90; 0.4, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2; −0.3, −0.3], respectively.

CZ waveform parameters transformation

Construction of Clifford gate

I, X/2, −X/2, Y/2, −Y/2 are the five single-qubit gates which together form the 24-member single-qubit Clifford group: I, X/2, −X/2, Y/2, −Y/2, (X/2)(Y/2), (X/2)(−Y/2), (−X/2)(Y/2), (−X/2)(−Y/2), (Y/2)(X/2), (Y/2)(−X/2), (−Y/2)(X/2), (−Y/2)(−X/2), (X/2)(X/2), (Y/2)(Y/2), (Y/2)(Y/2)(X/2)(X/2), (−X/2)(Y/2)(X/2), (−X/2)(−Y/2)(X/2), (X/2)(Y/2)(X/2), (−X/2)(Y/2)(−X/2), (X/2)(X/2)(Y/2), (X/2)(X/2)(−Y/2), (Y/2)(Y/2)(X/2), and (Y/2)(Y/2)(−X/2).

By introducing a two-qubit entangling gate such as the CZ gate, we can construct the two-qubit Clifford group containing 11,520 members. The construction of this group can be found in the Supplementary Material of ref. 3

On-chip optimisation and calibration

The time overhead for one function evaluation on-chip is 50 s. We use 25 s to apply an RB sequence and 25 s to apply probing pulses, used for real-time calibration. The whole optimisation takes 120 evaluations, which amounts to 6000 s for on-chip optimisation. Considering data packet loss and reoperation, total operation time may increase to about 2 h.

RB measurement

Each fidelity is obtained by averaging the fidelity of 100 random RB sequences and each fidelity of random RB sequences is obtained by 1000 single-shot measurements. Each of single-shot measurement takes 250 μs, including the RB sequence, readout and qubit relaxation to zero. The total time to characterise one waveform takes up to 25 s.

Real-time calibration

During the 25 s of measuring fidelity, we alternately insert Ramsey sequence, readout sample sequence, decoherence time marked sequence for every 1 s and collect the data to do calibration, which takes another 25 s.

Z-pulse predistortion

We input a square pulse, which becomes distorted as it travels down the refrigerator, and measure the frequency of qubit by Ramsey. Since a distorted pulse will be change the frequency of the qubit, Ramsey measurments allow us to gain enough insight into the transfer function to predistort the pulses. We calibrated the pulse such that 20 ns after the pulse, the distortion is less than 10−4 times the pulse amplitude.

Estimation of decoherence error

We assume that every qubit has two decoherence channels: amplitude damping and phase dampling, which can be quantified by T1 and Tφ. We have analysed the effects of T1 and Tφ for idle gates. We define QPT fidelity as F = Tr(χidleχdecoherence) and find F = 1 − Tgate/(2T1) − Tgate/(2Tφ) when Tgate ≪ T1, Tφ. In experiment, we measured the T1 and idle gate fidelity (by RB), and then calculated Tφ. We substituted the T1 and Tφ of both qubits into the formula for nonadiabatic CZ gate decoherence error and found the decoherent error to be 0.22% for the CZ gate.

Data availability

Data available on request from the authors.

Code availability

Code available on request from the authors.

References

Boixo, S. et al. Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices. Nat. Phys. 14, 595–600 (2018).

Moll, N. et al. Quantum optimization using variational algorithms on near-term quantum devices. Quantum Sci. Technol. 3, 030503 (2018).

Barends, R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500 (2014).

Barends, R. et al. Diabatic Gates For Frequency-tunable Superconducting Qubits. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.02510 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Measuring and suppressing quantum state leakage in a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 020501 (2016).

Heeres, R. W. et al. Implementing a universal gate set on a logical qubit encoded in an oscillator. Nat. Commun. 8, 94 (2017).

McKay, D. C. et al. Universal gate for fixed-frequency qubits via a tunable bus. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 064007 (2016).

DiCarlo, L. et al. Demonstration of two-qubit algorithms with a superconducting quantum processor. Nature 460, 240–244 (2009).

Rosenblum, S. et al. A cnot gate between multiphoton qubits encoded in two cavities. Nat. Commun. 9, 652 (2018).

Felicetti, S. et al. Dynamical casimir effect entangles artificial atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 093602 (2014).

Reagor, M. et al. Demonstration of universal parametric entangling gates on a multi-qubit lattice. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao3603 (2018).

Wendin, G. Quantum information processing with superconducting circuits: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 106001 (2017).

Benhelm, J., Kirchmair, G., Roos, C. F. & Blatt, R. Towards fault-tolerant quantum computing with trapped ions. Nat. Phys. 4, 463–466 (2008).

Veldhorst, M. et al. A two-qubit logic gate in silicon. Nature 526, 410 (2015).

Rong, X. et al. Experimental fault-tolerant universal quantum gates with solid-state spins under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8748 (2015).

Zopes, J. et al. High-resolution quantum sensing with shaped control pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 260501 (2017).

Martinis, J. M. & Geller, M. R. Fast adiabatic qubit gates using only σ z control. Phys. Rev. A 90, 022307 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. An efficient and compact switch for quantum circuits. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 50 (2018).

Rigetti, C. & Devoret, M. Fully microwave-tunable universal gates in superconducting qubits with linear couplings and fixed transition frequencies. Phys. Rev. B 81, 134507 (2010).

Sheldon, S., Magesan, E., Chow, J. M. & Gambetta, J. M. Procedure for systematically tuning up cross-talk in the cross-resonance gate. Phys. Rev. A 93, 060302 (2016).

Song, C. et al. Continuous-variable geometric phase and its manipulation for quantum computation in a superconducting circuit. Nat. Commun. 8, 1061 (2017).

Paik, H. et al. Experimental demonstration of a resonator-induced phase gate in a multiqubit circuit-qed system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 250502 (2016).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Strauch, F. W. et al. Quantum logic gates for coupled superconducting phase qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 167005 (2003).

Mallipeddi, R. & Suganthan, P. N. Differential evolution algorithm with ensemble of parameters and mutation and crossover strategies. In (eds Panigrahi, B. K., Das, S., Suganthan, P. N. & Dash, S. S.) Swarm, Evolutionary, and Memetic Computing 71–78 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010).

Zahedinejad, E., Ghosh, J. & Sanders, B. C. High-fidelity single-shot toffoli gate via quantum control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 200502 (2015).

Palittapongarnpim, P., Wittek, P., Zahedinejad, E., Vedaie, S. & Sanders, B. C. Learning in quantum control: High-dimensional global optimization for noisy quantum dynamics. Neurocomputing 268, 116–126 (2017).

Nöbauer, T. et al. Smooth optimal quantum control for robust solid-state spin magnetometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 190801 (2015).

Poggiali, F., Cappellaro, P. & Fabbri, N. Optimal control for one-qubit quantum sensing. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021059 (2018).

Machnes, S., Assémat, E., Tannor, D. & Wilhelm, F. K. Tunable, flexible, and efficient optimization of control pulses for practical qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 150401 (2018).

Nelder, J. A. & Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Computer J. 7, 308–313 (1965).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007).

Barends, R. et al. Coherent josephson qubit suitable for scalable quantum integrated circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 080502 (2013).

Mohseni, M., Rezakhani, A. T. & Lidar, D. A. Quantum-process tomography: Resource analysis of different strategies. Phys. Rev. A 77, 032322 (2008).

Merkel, S. T. et al. Self-consistent quantum process tomography. Phys. Rev. A 87, 062119 (2013).

Reed, M. D. et al. Realization of three-qubit quantum error correction with superconducting circuits. Nature 482, 382 (2012).

Kelly, J. et al. Optimal quantum control using randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 240504 (2014).

Glaser, S. J. et al. Training schrödinger’s cat: quantum optimal control. Eur. Phys. J. D. 69, 279 (2015).

Ristè, D., Bultink, C. C., Lehnert, K. W. & DiCarlo, L. Feedback control of a solid-state qubit using high-fidelity projective measurement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 240502 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the USTC Center for Micro- and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication, Institute of Physics CAS, and National Center for Nanoscience and Technology for their support of the sample fabrication. We acknowledge Barry C. Sanders for discussions of search algorithms and Xiongfeng Ma for advise with CCZ benchmark methods. This work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication. This research was supported by the National Basic Research Programme (973) of China (Grant no. 2017YFA0304300), the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Anhui Initiative in Quantum Information Technologies, Technology Committee of Shanghai Municipality, National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 11574380)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.-B.Z. and J.-W.P. conceived the research. S.-W.L. did the numerical simulation and on-chip experiment. S.-W.L. and A.D.C. analysed the search algorithm and the theory of nonadiabatic CZ gates. S.Y.W. designed the qubit. Y.L.W. developed the programming platform for experiment and S.-W.L. improved the accuracy of the calibration and ability to resist noise. M.G. provided suggestions on experiment. C.Z. provided suggestions on numerical simulation. Z.-G.Y., R.H. and H.D. prepared the sample. C.G., L.-H.S. and C.-Z.P. developed the room temperature electronics. S.-W.L., A.D.C. and X.-B.Z. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Castellano, A.D., Wang, S. et al. Realisation of high-fidelity nonadiabatic CZ gates with superconducting qubits. npj Quantum Inf 5, 84 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0202-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0202-7

This article is cited by

-

Noisy intermediate-scale quantum computers

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Scalable algorithm simplification using quantum AND logic

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Control System of Superconducting Quantum Computers

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2022)