Abstract

Medium-scale ensembles of coupled qubits offer a platform for near-term quantum technologies as well as studies of many-body physics. A central challenge for coherent control of such systems is the ability to measure individual quantum states without disturbing nearby qubits. Here, we demonstrate the measurement of individual qubit states in a sub-diffraction cluster by selectively exciting spectrally distinguishable nitrogen vacancy centers. We perform super-resolution localization of single centers with nanometer spatial resolution, as well as individual control and readout of spin populations. These measurements indicate a readout-induced crosstalk on non-addressed qubits below 4 × 10−2. This approach opens the door to high-speed control and measurement of qubit registers in mesoscopic spin clusters, with applications ranging from entanglement-enhanced sensors to error-corrected qubit registers to multiplexed quantum repeater nodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atom-like emitters in solids1 have emerged as promising quantum memories for computing,2 sensing,3 and the study of mesoscopic quantum systems.4,5,6 In particular, the negatively charged nitrogen vacancy (NV) center in diamond7 is a leading spin qubit due to its long coherence time8 and coherent optical interface.9 Control over the electron spin and nearby nuclear spins has enabled local10 and photon-mediated distant11 entanglement between NV electron spins, sensing enhanced by quantum logic,12 and quantum error correction.13,14 These systems have been scaled past two qubits by utilizing nuclear spins15 and dark electron spins,16 and preliminary progress has been made towards scaling using additional NV electron spins.17,18 These advances suggest that a system of strongly coupled color centers, each coupled to proximal dark spins, could provide a scalable platform for controlled spin–spin interactions, as illustrated in Fig. 1a.

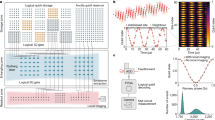

Preferential excitation and imaging of sub-diffraction defects. a An ensemble of nitrogen vacancy (NV) electron spins (red) coupled to nearby nuclear spins (yellow) with distinct optical transition frequencies due to local strain fields, allowing selective interaction with individual centers operating on different frequency channels within a diffraction-limited spot. b NV electron level structure. A ground state spin triplet acts as a qubit, addressable via 2.88 GHz microwave driving (blue). The spin-conserving radiative transitions (red) are at distinct frequencies, allowing optical spin readout via resonant excitation. Axial (σ||) and transverse (σ⊥) strains shift these levels further and may distinguish individual NVs. c Confocal microscope image of the polycrystalline diamond (PCD) showing the microwave stripline. The bright white line is a grain boundary in the diamond. Inset, a close-up scan showing a brighter spot at site 1, determined to be a cluster of NVs, as well as a dimmer spot at site 2, determined to be a single NV. d Histogram (N = 87) showing the inhomogeneous distribution of zero-phonon line (ZPL) transitions measured via photoluminescence excitation (PLE) in the PCD, with a standard deviation σ = 294 GHz. e PLE on the NV cluster at site 1, showing multiple transitions from strain-split centers, fit to a sum of seven Lorentzians (red). f Reconstructed locations within the cluster, with width (standard deviation) indicating the standard distance error on each point, multiplied 10× for visibility. For comparison, the dashed line shows the full-width half-maximum size of the spot under 532 nm excitation

Such an architecture requires NV separation on the order of 10 nm for fast entanglement gates,10 raising the problem of individual qubit addressing. Current super-resolution techniques19,20 can reach this resolution, but are destructive to the states of nearby qubits, precluding their use for generalized quantum control. Here, we address this problem by making use of the inhomogeneous distribution of NV center optical transitions, attributed to natural and defect-induced lattice strain.21,22 The strain field \(\vec \sigma\) enters the excited state Hamiltonian as \(H_{{\mathrm{strain}}} = \vec \sigma \cdot \vec V\),23 where \(\vec V\) is the vector of orbital operators, and can be divided into axial and transverse components, with differing effects detailed in Fig. 1b. We find that this distribution persists even for closely spaced NV centers, allowing us to optically address individual emitters within a diffraction-limited volume.

Results

We investigate this approach to multi-qubit readout in a Type IIa polycrystalline diamond (PCD). The scanning confocal image in Fig. 1c shows NV centers in one domain of this PCD near a gold stripline for microwave delivery that cuts across a grain boundary, visible as the bright strip in the image. Despite the high strain of the PCD,24 its low nitrogen content allows for NVs with coherence times exceeding 200 µs (see Supplementary Fig. 2) at room temperature. The histogram of the NV optical transitions (Fig. 1d) indicates an inhomogeneous distribution with standard deviation of 294 GHz, nearly five times broader than what we measure in single-crystal diamond (SCD) samples.

Super-resolution localization

This broad inhomogeneous distribution allows us to spectrally distinguish NVs below the diffraction limit. Figure 1e shows a photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectrum taken on a representative fluorescence site on the sample, labeled site 1 in the inset of Fig. 1c. The spectrum reveals several distinct zero-phonon line (ZPL) peaks, indicative of the presence of multiple NV centers within the diffraction-limited spot. Spatially scanning a narrow laser resonant with one of the transitions in Fig. 1e preferentially induces fluorescence from a single NV center, selectively imaging this defect out of the cluster. Performing this scan for each observed transition, we find that they correspond to only three spatial positions. Second-order autocorrelation and optically detected magnetic resonance measurements further confirm the presence of three NV centers in this site. The most prominent and well-isolated peaks for each NV center are labeled as A, B, and C in Fig. 1e. For these transitions, we repeat the resonant imaging experiment, each time fitting the result with a Gaussian point-spread function. The standard error on the fit centers gives a localization precision of 〈SA〉 = 0.45 nm for the brightest and most spectrally distinct NV (see Supplementary Information for details). Figure 1f shows the reconstructed positions, with spot widths indicating 10 times the localization precision after 40 min of integration and the dashed overlay showing the full-width half-maximum size of the original diffraction-limited spot.

Readout-induced crosstalk

We next consider the crosstalk that an optical readout of one NV induces in other NVs in a diffraction-limited spot. For simplicity, we first study these dynamics in a simple spin-1 system associated with a single NV center (NVD) in site 2 of Fig. 1c, which is initialized into state |ψ0〉 = |ms = 0〉 + |ms = 1〉. Suppose a laser is applied at frequency ωL for time T to perform resonant readout on a hypothetical neighboring NV. This laser non-resonantly excites NVD from ground state |i〉 into excited state |j〉, projecting its state by spontaneous emission into ground state |k〉, where i, k ∈ ms = {−1, 0, 1} and j ∈ {E1, E2, Ex, Ey, A1, A2}, with probability (see Supplementary Information):

where Δij is the detuning of ωL from NVD’s |i〉 → |j〉 ground-to-excited state transition, Ωij is the optical Rabi frequency, and γjk is the excited state’s decay rate into |k〉. In addition to such a spontaneous-emission-induced state projection, NVD may also acquire a phase shift due to the AC stark shift of the applied laser; however, this is a weak and coherent process and can be compensated (see Supplementary Information).

We probe this laser-induced crosstalk using Ramsey interferometry, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The application of an off-resonant laser (detuned by Δ from NVD’s Ex transition) for fixed time T during the free precession period τ projects the NV into the mixed state:

where \(\left| \psi \right\rangle = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\left| 0 \right\rangle + e^{ - i\theta (t)}\left| 1 \right\rangle } \right)\) is the result of the Ramsey experiment and \({\sum} {\Gamma _{ijk}} = \Gamma\). The summed terms in Eq. (2) are stationary states and provide no contrast in the Ramsey experiment, such that the fringe amplitude is directly proportional to 1 − Γ (see Supplementary Information). The final spin state (after the second π/2 pulse of the Ramsey sequence) is measured by state-dependent fluorescence F through 532 nm illumination. F is normalized to account for power fluctuations by repeating the sequence, but replacing the final π/2 gate with a 3π/2 gate and taking the contrast \(C = \frac{{(F_{3\pi /2} - F_{\pi /2})}}{{(F_{3\pi /2} + F_{\pi /2})}}\).

Qubit degradation under near-resonant excitation for a single isolated nitrogen vacancy (NV). a Bloch sphere schematic for crosstalk measurement sequence. After a π/2 pulse prepares the qubit in a superposition state, it precesses around the Bloch sphere during application of a near-resonant laser. With probability (1 − Γ), the laser will not induce excitation and subsequent decay, preserving the phase built up during the precession period, which is then mapped into population by a second π/2 pulse and read out with a non-resonant readout pulse. However, the laser may also induce a spin-projecting decay event; in this scenario, the second π/2 pulse will always place the spin in an even superposition state, independent of any phase accumulated during the precessionary period, leading to a precession time-independent intensity at the final readout. b Ramsey sequences with a resonant laser of varying detunings applied during the free precession period. The fits (solid lines) have one fit parameter for the fringe amplitude relative to that of a reference Ramsey taken with no crosstalk laser. c Crosstalk probability as a function of laser detuning, taken by fixing the precession time to the fringe maximum at τ = 386 ns (dashed line in b) and sweeping the resonant laser detuning. The contrast values are normalized to the fringe amplitude from the no-laser case. In red, the model for Γ (Eq. 1) with one fit parameter for the optical Rabi frequency. Error bars in b, c show standard error

Figure 2b plots C for varying Δ. For Δ = 0, the Ramsey contrast vanishes, as expected for the laser-induced state projection. With increasing detuning, the fringe contrast recovers, approaching a control experiment without the readout laser.

We map the crosstalk as a function of Δ by fixing the precession time to the fringe maximum at 386 ns and sweeping the resonant laser over a wide range of detunings. These data are converted to a bit error probability in Fig. 2c by normalizing the fluorescence from each detuning to that from the reference “no-laser” control experiment (Fig. 2b), which gives the crosstalk-free case. The red curve represents our model from Eq. (1) with only one fit parameter for the optical Rabi frequency, which is difficult to accurately measure experimentally due to spectral diffusion of the ZPL. The optical excitation time T is fixed by our pulse generator, and the decay rate is determined by lifetime characterization. The theory shows good agreement with our data and indicates that a detuning of 16 GHz or greater keeps crosstalk errors below 1%, a regime accessible by the cluster at site 1 of Fig. 1c.

Low-crosstalk readout of individual qubits

We now demonstrate individual control and readout on this cluster. We achieve independent microwave control of the spin states by applying a magnetic field, which splits the spin levels depending on the NV center crystal orientation. In this cluster, we find that two of the NV centers (A and B) are oriented along one crystal axis and the third (C) along another, indicated by four dips in the magnetic resonance spectrum (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

We take advantage of this ground state splitting and apply the same Ramsey sequence from above to perform individual control and readout. Figure 3a shows the gate representation of our sequence. After initialization of all three NV centers with a 532 nm repump, the spin of NV C is coherently driven with a resonant microwave pulse for a time τ, inducing Rabi oscillations corresponding to a rotation of angle θ about the X-axis. Next, NVs A and B are rotated into an equal superposition state by a π/2 pulse, followed by a passive precession by angle ϕ about the Z-axis for the same time τ. While NVs A and B are in this phase-sensitive superposition state, we perform individual readout on NV C using a resonant optical pulse. After waiting a total precession time τ, a final π/2 pulse completes the Ramsey sequence on NVs A and B, and we read out these states with 532 nm light (see Supplementary Information for details). Note that while limitations in the available equipment necessitated the use of a non-resonant green readout on NVs A and B, additional lasers or modulators would allow for individual readout of each NV center in the cluster. Figure 3b shows the results of each readout window, where both gates measure the expected Rabi and Ramsey signals. Comparing these Ramsey results to that of a control Ramsey experiment on NVs A and B taken with no additional control or readout sequences on NV C, the fringe amplitudes are equal within our noise bounds (0 ± 4% bit error probability). That is, we find no detectable fringe amplitude degradation as a result of the resonant readout pulse, indicating that the states of the off-resonant NV centers are left unperturbed through this readout. This result is consistent with our model, which predicts a bit error probability of ~1%, below the 4% fit bounds.

Simultaneous control and readout of three nitrogen vacancies (NVs) in a sub-diffraction volume. a Gate sequence for demonstrating simultaneous control and readout of multiple NVs. A Rabi sequence is performed on NV C, followed by a subsequent Ramsey sequence on NVs A and B. During the Ramsey sequence, the state of NV C is read out using resonant readout (RR). The RR gate is depicted as partially spilling into |ψ〉AB to indicate the possibility of crosstalk. b Results of the sequence in a, showing Rabi oscillations on NV C (red circles) and Ramsey fringes for NVs A and B (green upward triangles), alongside the reference Ramsey fringes (blue downward triangles) for NVs A and B taken with no Rabi sequence nor RR on NV C. The green fit to the data for |ψ〉AB indicates no signal degradation within measurement error bounds

Discussion

We assess the viability of this platform for scalable creation of multi-spin registers by considering the probability of forming systems of multiple distinguishable emitters. Figure 4a shows the inhomogeneous distribution of NV center ZPL frequencies acquired on an SCD from a dataset of 406 ZPL transitions from 197 distinct emitter sites. We consider here an SCD to allow comparison to samples most typically used in diamond quantum information experiments.5,13,25 From this distribution, we build an empirical kernel estimate (red curve, Fig. 4a).

Architecture scalability. a Histogram (blue bars) of 406 zero-phonon line (ZPL) resonance frequencies normalized to be in units of probability density, and corresponding kernel density estimate (red line) of this inhomogeneous distribution. b–d Simulated probabilities of successfully creating viable registers of varying numbers of nitrogen vacancies (NVs) under different tolerance thresholds for the probability Γ of undesired spontaneous decays from off-resonant NVs. b Results using multi-shot readout (MSR) parameters shown in this work and the low-strain single-crystal diamond (SCD) distribution in a. c Results using parameters used to demonstrate high-fidelity single-shot readout (SSR)25,26 and the low-strain SCD distribution in a. d Results using SSR parameters and the high-strain distribution measured in the polycrystalline diamond (PCD) sample from Figs. 1–3

Based on Monte Carlo sampling from this measured distribution and accounting for the full optical fine structure of the NV, we estimate the probability that N emitters in a cluster have a crosstalk probability ≤Γ under the parameters used for our multi-shot readout (MSR) in Fig. 2. These results are given in Fig. 4b. For example, the probability for an N = 3 NV site to have a crosstalk Γ ≤ 10−2 is estimated at 20%. If each of the NVs were coupled to three nuclear spin data qubits, such an N = 3 system would be sufficient for implementing the [[9,1,3]] Shor-Bacon code.26

Improved light collection using photonic microstructuring and single-shot readout (SSR)27 could improve these yields. To this end, we repeat our simulation under experimental parameters (Ω = γ, T = 3.7 µs) comparable to those used to achieve single-shot readout with 97% fidelity in a solid immersion lens.25 The results in Fig. 4c indicate an increase to 24% of the N = 3 yield discussed above. Keeping these readout parameters and additionally assuming the measured ZPL distribution for the PCD (Fig. 1d) produces the yield histogram in Fig. 4d, which shows that registers of N = 9 NVs with Γ ≤ 10−2 could be produced with 12% yield.

In conclusion, we demonstrated readout of individual solid-state qubits within a diffraction-limited cluster with crosstalk on non-addressed qubits below 4 × 10−2. This capability was enabled by strain-splitting of the NV centers’ ZPL transitions in a PCD. While this work uses native strain, the strain field may also be engineered28 to provide greater control and increase inhomogeneous distributions. If an application necessitates a low-strain environment, these resonances can also be shifted by applying a static electric field, allowing defects of different orientations—or the same orientation under a strong field gradient—to be uniquely addressed. The approach presented here is also applicable to other atom-like emitters, such as quantum dots,29 rare-earth ions,30 and other solid-state color centers. When combined with existing techniques for producing sub-diffraction clusters via aperture implantation,31 entangling defect centers with ancilla nuclear spins,15 and single-shot readout,27 this provides a path towards creating large ensembles of individually addressable qubits, with a number of applications. For example, error-corrected registers using the 7-qubit32 or 9-qubit26 codes could be constructed with clusters of multiple coupled NV-dark spin systems, with full connectivity given by spin–spin coupling between adjacent NV centers. This would allow extension of architectures comprising one optically active and multiple dark spins15 by reducing the problem of spectral crowding, as well as increasing the effective gate rate by parallelization. NV clusters with individual readout could also enable entanglement-assisted and spatially resolved nanoscopic quantum sensing.3 Finally, such clusters present an appealing architecture for modular quantum computing schemes33,34 and spectrally multiplexed quantum repeaters.35

Methods

Sample preparation

Super-resolution localization and individual control experiments were performed on a Type IIa PCD produced by chemical vapor deposition (Element 6), with a native nitrogen concentration of <50 ppb. To increase the prevalence of sub-diffraction clusters, the sample was implanted with nitrogen at 85 keV with a density of 1010 cm−2, and subsequently annealed at 1200 °C for 8 h. The conversion yield of this process is on the order of 1%, resulting in a final areal NV density of roughly 1 μm−2. For delivering microwaves, striplines of 100-nm-thick gold with a 5 nm titanium adhesion layer were fabricated via lift-off on the diamond surface. The single-crystal Type IIa diamond was also produced by chemical vapor deposition (Element 6), with a native nitrogen concentration of <5 ppb. NV centers in this sample were created by implanting nitrogen (energy 185 eV, dosage 109 cm−2) and subsequently annealing at 1200 °C for 8 h.

Experimental setup

Experiments were performed using a home-built scanning confocal microscope. The samples were cooled to 4 K using a closed-cycle helium cryostat (Montana Instruments) and were imaged through a 0.9 NA vacuum objective. Light (532 nm) was generated by a Coherent Verdi G5 laser, and resonant red light tunable around 637 nm was generated by a New Focus Velocity tunable diode laser. Microwave signals were generated by Rohde and Schwarz SMIQ06B and SMV03 signal generators and sent through a high-power amplifier (Mini-Circuits ZHL-16W-43+) before delivery to the sample.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gao, W. B., Imamoglu, A., Bernien, H. & Hanson, R. Coherent manipulation, measurement and entanglement of individual solid-state spins using optical fields. Nat. Photonics 9, 363 (2015).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. Observation of a discrete time crystal. Nature 543, 217 (2017).

Choi, S. et al. Observation of discrete time-crystalline order in a disordered dipolar many-body system. Nature 543, 221 (2017).

Mohammady, M. H. et al. Low-control and robust quantum refrigerator and applications with electronic spins in diamond. Phys. Rev. A 97, 042124 (2018).

Doherty, M. W. et al. The nitrogen-vacancy colour centre in diamond. Phys. Rep. 528, 1–45 (2013).

Bar-Gill, N., Pham, L. M., Jarmola, A., Budker, D. & Walsworth, R. L. Solid-state electronic spin coherence time approaching one second. Nat. Commun. 4, 1743 (2013).

Togan, E. et al. Quantum entanglement between an optical photon and a solid-state spin qubit. Nature 466, 730 (2010).

Dolde, F. et al. Room-temperature entanglement between single defect spins in diamond. Nat. Phys. 9, 139 (2013).

Humphreys, P. C. et al. Deterministic delivery of remote entanglement on a quantum network. Nature 558, 268–273 (2018).

Lovchinsky, I. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance detection and spectroscopy of single proteins using quantum logic. Science 351, 836–841 (2016).

Waldherr, G. et al. Quantum error correction in a solid-state hybrid spin register. Nature 506, 204–207 (2014).

Cramer, J. et al. Repeated quantum error correction on a continuously encoded qubit by real-time feedback. Nat. Commun. 7, 11526 (2016).

Abobeih, M. H. et al. One-second coherence for a single electron spin coupled to a multi-qubit nuclear-spin environment. Nat. Commun. 9, 2552 (2018).

Rosenfeld, E. L., Pham, L. M., Lukin, M. D. & Walsworth, R. L. Sensing coherent dynamics of electronic spin clusters in solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 243604 (2018).

Pfender, M. et al. Protecting a diamond quantum memory by charge state control. Nano Lett. 17, 5931–5937 (2017).

Bodenstedt, S. et al. Nanoscale spin manipulation with pulsed magnetic gradient fields from a hard disc drive writer. Nano Lett. 18, 5389–5395 (2018).

Chen, E. H., Gaathon, O., Trusheim, M. E. & Englund, D. Wide-field multispectral super-resolution imaging using spin-dependent fluorescence in nanodiamonds. Nano Lett. 13, 2073–2077 (2013).

Jaskula, J.-C. et al. Superresolution optical magnetic imaging and spectroscopy using individual electronic spins in diamond. Opt. Express 25, 11048–11064 (2017).

Bernien, H. et al. Two-photon quantum interference from separate nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 043604 (2012).

Sipahigil, A. et al. Indistinguishable photons from separated silicon-vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 113602 (2014).

Doherty, M. W., Manson, N. B., Delaney, P. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. The negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond: the electronic solution. N. J. Phys. 13, 025019 (2011).

Trusheim, M. E. & Englund, D. Wide-field strain imaging with preferentially aligned nitrogen-vacancy centers in polycrystalline diamond. N. J. Phys. 18, 123023 (2016).

Hensen, B. et al. Loophole-free bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature 526, 682 (2015).

Bacon, D. Operator quantum error-correcting subsystems for self-correcting quantum memories. Phys. Rev. A 73, 012340 (2006).

Robledo, L. et al. High-fidelity projective read-out of a solid-state spin quantum register. Nature 477, 574 (2011).

Meesala, S. et al. Strain engineering of the silicon-vacancy center in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 97, 205444 (2018).

Press, D., Ladd, T. D., Zhang, B. & Yamamoto, Y. Complete quantum control of a single quantum dot spin using ultrafast optical pulses. Nature 456, 218 (2008).

Dibos, A. M., Raha, M., Phenicie, C. M. & Thompson, J. D. Atomic source of single photons in the telecom band. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 243601 (2018).

Jakobi, I. et al. Efficient creation of dipolar coupled nitrogen-vacancy spin qubits in diamond. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 752, 012001 (2016).

Steane, A. M. Error correcting codes in quantum theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 793–797 (1996).

Nickerson, N. H., Fitzsimons, J. F. & Benjamin, S. C. Freely scalable quantum technologies using cells of 5-to-50 qubits with very lossy and noisy photonic links. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041041 (2014).

Pant, M., Choi, H., Guha, S. & Englund, D. Percolation based architecture for cluster state creation using photon-mediated entanglement between atomic memories. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1704.07292 (2017).

Sinclair, N. et al. Spectral multiplexing for scalable quantum photonics using an atomic frequency comb quantum memory and feed-forward control. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 053603 (2014).

Acknowledgements

E.B. was supported by a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship and the NSF Center for Ultracold Atoms (CUA). M.W. was supported by the STC Center for Integrated Quantum Materials (CIQM), NSF Grant No. DMR-1231319, the Army Research Laboratory Center for Distributed Quantum Information (CDQI), and Master Dynamic Limited. S.L.M. was supported by the NSF EFRI-ACQUIRE program Scalable Quantum Communications with Error-Corrected Semiconductor Qubits and the AFOSR Quantum Memories MURI. M.E.T. was supported by an appointment to the Intelligence Community Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Program at MIT, administered by Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. T.S. was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 753067 (OPHOCS) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany (BMBF, DiNOQuant, project number 13N14921). This work was supported in part by the AFOSR MURI for Optimal Measurements for Scalable Quantum Technologies (FA9550-14-1-0052) and by the AFOSR program FA9550-16-1-0391, supervised by Gernot Pomrenke. We would like to thank C. Foy, H. Choi, and C. Peng for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B. and M.W. contributed equally to this work. E.B. and M.W. performed the experiments. E.B. and T.S. constructed the optical setup. S.L.M., M.E.T., and M.W. prepared the sample. E.B., M.W., M.E.T., T.S., and D.R.E. conceived the experiments. E.B., M.W., S.L.M., and D.R.E. prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bersin, E., Walsh, M., Mouradian, S.L. et al. Individual control and readout of qubits in a sub-diffraction volume. npj Quantum Inf 5, 38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0154-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0154-y

This article is cited by

-

Reversible optical data storage below the diffraction limit

Nature Nanotechnology (2024)

-

Field programmable spin arrays for scalable quantum repeaters

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Large-scale optical characterization of solid-state quantum emitters

Nature Materials (2023)

-

Quantum guidelines for solid-state spin defects

Nature Reviews Materials (2021)

-

A phononic interface between a superconducting quantum processor and quantum networked spin memories

npj Quantum Information (2021)