Abstract

Spin–orbit coupling (SOC) is fundamental to a wide range of phenomena in condensed matter, spanning from a renormalisation of the free-electron g-factor, to the formation of topological insulators, and Majorana Fermions. SOC has also profound implications in spin-based quantum information, where it is known to limit spin lifetimes (T1) in the inversion asymmetric semiconductors such as GaAs. However, for electrons in silicon—and in particular those bound to phosphorus donor qubits—SOC is usually regarded weak, allowing for spin lifetimes of minutes in the bulk. Surprisingly, however, in a nanoelectronic device donor spin lifetimes have only reached values of seconds. Here, we reconcile this difference by demonstrating that electric field induced SOC can dominate spin relaxation of donor-bound electrons. Eliminating this lifetime-limiting effect by careful alignment of an external vector magnetic field in an atomically engineered device, allows us to reach the bulk-limit of spin-relaxation times. Given the unexpected strength of SOC in the technologically relevant silicon platform, we anticipate that our results will stimulate future theoretical and experimental investigation of phenomena that rely on strong magnetoelectric coupling of atomically confined spins.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individual spins confined to solids are attracting considerable interest due to their potential as quantum bits (qubits) in future quantum information processors.1,2 In particular, electron spins bound to phosphorus donors have demonstrated exceptionally long spin life (T1) and coherence (T2) times, both of order seconds in isotopically purified 28Si.3 Recent demonstrations of high-fidelity4 spin readout,5 manipulation,6 and controllable exchange,7,8 promise the realisation of scalable donor-based quantum computing.2,9

One reason for the extremely long spin lifetimes of electrons in silicon is their inherently weak spin–orbit coupling (SOC), which has been found to dominate spin relaxation in inversion asymmetric polar semiconductors, such as GaAs.10,11,12 In the absence of surfaces and interfaces,13,14 SOC for electrons in silicon is usually considered negligible15 due to its small atomic number and large band gap. In fact, the presence of bulk-inversion symmetry in silicon fundamentally excludes Dresselhaus SOC, whilst structural inversion symmetry precludes Rashba SOC for the spherically symmetric ground state wave function of bulk donors. As a consequence, for donor-bound electrons SOC enters spin-lattice relaxation only as a weak time-dependent perturbation of spin–valley states via deformation potential phonons.16,17,18 Typically, this has resulted in extended spin lifetimes, exceeding those in GaAs by more than an order of magnitude.10,11,12

However, unlike donors in bulk silicon, individual donors as quantum bits in nanoelectronic devices4,5,19 experience electric fields (several MV/m7,15,20), that are known to have a profound effect on the donor wave function, modifying charging energies,21,22,23 valley–orbit splitting,22,24,25 and Stark shift of the electron’s g-factor,26 as well as ultimately the nuclear hyperfine and exchange coupling.2,9 The strength and vectorial nature of such electric fields can be expected to reduce crystal symmetry,27 introducing higher-order coupling of spins with their electromagnetic environment, thus impacting spin lifetimes and coherence.

In this paper, we report the presence of such electric field induced magnetoelectric coupling for the first time, using measurements of electron spin-relaxation rates of an individual Si:P donor qubit within an atomically engineered nanoelectronic device. Comparing to well-established theoretical frameworks16,17 and measurements28 of bulk donors, we find a profoundly different magnetic field anisotropy of spin-relaxation rates in both periodicity and phase, with a difference in spin-relaxation rates by more than one order of magnitude for certain magnetic field orientations.

We explain this unusual spin-relaxation anisotropy by a coupling,27,29

of spin and external electric (E) and magnetic (B) fields, where σ is the electron spin and C is a tensor representing the strength of this SOC interaction along the Cartesian directions arising from directional differences in single valleys as well as the valley weights of the wave function (see Supplementary Information Section 4). In line with conventional SOC, the above Hamiltonian can be derived as a higher-order perturbation from k·p theory,29 and induces an effective magnetic field Beff. However, unlike conventional SOC, the particular structure of HEB demands that for external magnetic fields applied along the main symmetry axes, this effective field is oriented perpendicular to the spin quantisation axis, allowing effective mixing of spin states facilitating fast spin relaxation. Whilst a related magnetoelectric coupling has been theoretically predicted for acceptors27 with known strong SOC30 more than 5 decades ago, it has never been observed experimentally, nor considered in donor spin-relaxation theory. Demonstrating its impact on spin relaxation in the controlled electromagnetic environment of an atomically engineered nanoelectronic device, we thus solve a long-standing mystery as per why spin lifetimes in silicon devices (~sec) have been found substantially shorter,5,15 compared to those in bulk (~min).28 Indeed, we show that careful design of the local electromagnetic environment in nanoelectronic devices allows us to eliminate these lifetime-limiting effects—an important factor in designing future qubit architectures—and allow us to demonstrate the bulk-limit of donor spin lifetimes within a nanoelectronic device for the first time.

Results

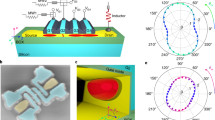

An overview scanning tunneling microscope (STM) image of the nanoelectronic device (see Methods) is shown in Fig. 1a. A single Si:P donor qubit was placed at the dashed white circle,4 d ~20 nm from the island of a single electron transistor (SET). Four in-plane gates (G1,2, GSET and GT) tune the donor and SET electrochemical potentials with a dominant electric field Ey ≃ 5 MV/m along the GT − GSET axis to facilitate spin readout (green arrow, see electrostatic model in Fig. 3). The diagram in Fig. 1b shows the respective orientations of Ey (green), the external magnetic field B (blue), as well as the effective HEB magnetic field Beff (red). The angles θ and ϕ enclose out-of-plane (θ) and in-plane (φ) alignments of B.

Impact of the electromagnetic environment on a single P donor qubit in a nanoelectronic device. a Overview STM image of the readout device after hydrogen lithography, showing an SET charge sensor with source (S) and drain (D) electrodes, and four electrostatic gates (G1,2, GT and GSET). A 31P donor qubit was placed within the dashed white circle. Jagged lines horizontally across the image are atomic step edges on the Si(001)-2 × 1 surface. Inset: atomic-resolution close-up, showing the placement of the donor with respect to the SET island, as well as the orientation of the silicon dimer-rows parallel to [110]. b Alignment of the external magnetic field B (blue arrow) and dominant electric field Ey (green arrow), giving rise to an effective magnetic field Beff (red arrow). c Energy level diagram of a Si:P donor. d Measured spin-relaxation rates of bulk donors (black circles),28 rescaled to the low-temperature limit5 and B = 3.5 T, compared to valley repopulation (dashed black), single-valley (dashed light grey) theories, and their sum (solid black). e Spin-relaxation anisotropy measured for a single Si:P qubit in the nanoelectronic device of (a). The solid red line shows a fit to HEB theory. f Spin-relaxation rates 1/T1(B) along [001], [111] and [110], with a clear B5-dependence. Deviations at low-magnetic fields are likely due to dipole–dipole magnetic coupling with substrate dopants,3,5 or due to charge noise.31 Grey data points indicate spin readout using the D− charge state.4 Black arrows indicate B = 3.5 T used in our anisotropy measurements

Spin-lattice relaxation in silicon is strongly influenced by the structure of its conduction band with six degenerate valleys. At the donor site (Fig. 1c), the sixfold degeneracy is broken into a spin-degenerate 1s(A1) ground state, with valley–orbit doublet 1s(E) and triplet 1s(T2) excited states. Spin-lattice relaxation within the 1s(A1) ground state occurs as acoustic deformation potential phonons modulate the electron g-tensor by inducing a time-dependent lattice strain.16,17 SOC mixes the donor ground state with the higher 1s excited states separated from the 1s(A1) ground state by the valley–orbit splitting Evo (Hasegawa’s valley repopulation mechanism)16 or with continuum states inside the same conduction band valley (Roth’s single-valley mechanism).17 Both valley-repopulation and single-valley theories predict a dependency of the spin-relaxation rate on the magnitude of the external magnetic field, 1/T1 ∝ B5 (low-temperature limit5), with a characteristic anisotropy depending on the alignment of the magnetic field vector with the crystal symmetry axes.16,17 For bulk donors, Wilson and Feher28 confirmed in the early 1960s that spin-relaxation rates could be described by a combination of valley-repopulation and single-valley contributions, with measured spin lifetimes of up to 18 min at 1.25 K and at a weak magnetic field, B = 0.8 T. To compare with our own measurements, performed at higher magnetic fields, we replot their experimental data at 1 K (black circles), rescaled to B = 3.5 T in the low-temperature limit5 (Fig. 1d), showing maximum spin lifetimes T1 ≃ 1.25 s for B||[001].

Our measurement of spin-relaxation rates for a single donor in a nanoelectronic device at the same magnetic field strength is shown in Fig. 1e. Here, we observe a profoundly different magnetic field anisotropy in magnitude, periodicity and phase. Along B||[001] and at B = 3.5 T, we find T1 ≃ 40 ms—a factor ~30 lower than bulk donors at the same magnetic field and temperature, consistent with previous measurements of donors in a nanoelectronic device at the same magnetic field.4,5 This large discrepancy in T1 obtained, compared to bulk donors, and combined with the observation of a fundamentally different spin-relaxation anisotropy, underpins the presence of a previously unreported spin-relaxation pathway. We note that T1 ∝ B5, as shown in Fig. 1f, so that spin lifetimes are of order seconds at B = 1.5 T for all magnetic field orientations, in agreement with previous single dopant devices.5 Consistency across two separate measurement cooldowns of the device and two different planes of rotation (out-of-plane (θ) and in-plane (φ)), is demonstrated in Fig. 2a–c. Indeed, here we recover T1 = 1.25 s at B||[010] and B = 3.5 T, comparable to that in bulk samples at the same magnetic field and temperature (Fig. 1d).

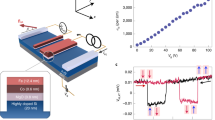

Magnetic field anisotropy of spin-relaxation rates in a nanoelectronic device. a, b Spin-relaxation anisotropy measured for two different planes of rotation, out-of-plane (θ) and in-plane (φ). Solid red and blue lines show fits to the data based on HEB coupling as detailed in the main text. c A graphical (3D) representation in the entire θ − φ plane. C and R have been used as extracted from the out-of-plane (θ) rotation. (The shaded surface in the figure is offset by −10 s−1 to avoid masking of data points)

Discussion

To explain the observed spin-relaxation anisotropy, we turn to the full effective mass Hamiltonian for donor electron spins in an electric field, expanded up to fourth order in perturbation theory29

Here, \(H_{\mathrm{Z}} = {\textstyle{{\mu _{\mathrm{B}}} \over 2}}\sigma \cdot {\bf{g}} \cdot B\) is the Zeeman Hamiltonian (second order perturbation) with the g-tensor according to Roth,17,18 HR = σ · R · (E × k) is the bulk Rashba Hamiltonian (third order), and HEB the Hamiltonian introduced in Eq. (1) (fourth order). This terms arises in an inversion asymmetric system in the presence of both electric and magnetic fields, and in our specific case, is influenced by the anisotropic multivalley nature of the conduction band. Different from bulk donors, both HR and HEB can be shown to enter valley-repopulation theory for donors in nanoelectronic devices (see Supplementary Information), dominating spin-relaxation rates and anisotropy in the presence of external electric fields.

Donor qubits in electric fields are thus different from other, inversion asymmetric, electronic systems—such as semiconductor quantum dots11,31—in which electronic wave functions are confined by interfaces, and in which the effect of any higher-order magnetoelectric coupling is dwarfed by lower order Rashba and Dresselhaus SOC terms. Atomically confined spins in low-SOC materials—such as P donors in silicon—typically have spherically symmetric ground state wave functions, and hence negligible Rashba and Dresselhaus SOC due to inversion symmetry. Although electric fields from nearby gate electrodes can introduce a non-negligible bulk Rashba contribution in donors, its effects are much weaker compared to quantum dots as the donor wave function remains strongly bound to the Coulomb potential over a wide range of realistic electric field strengths. Indeed, our calculation shows that the ratio of the coupling constants is given by (see Supplementary Information).

Here, (ħ/m0)pμν = 1.5 × 10−10 eV is the momentum matrix element between the silicon valence bands, evaluated at the conduction band minimum, and Eαμ ~ 4 eV is the energy difference between the conduction band minimum and the valence band, both at k0. μ and ν are the indices of the two highest valence bands, α is the index of the lowest conduction band, and k0 is the momentum vector where the conduction band minimum occurs.

Single-shot spin readout of donor-bound electrons requires the application of considerable gate electric fields20 to bring the Zeeman-split donor ground state into resonance with the electrochemical potential of a single-electron transistor charge sensor. Such electric fields, together with the external magnetic field thus induce an effective magnetic field, |Beff|, that is oriented normal to the external magnetic field orientation when aligned along one of the main symmetry axes (compare Fig.1b). In this case, the magnitude of this field maximises whenever B⊥E and is reduced to zero when they are aligned. From an electrostatic model of our device (Fig. 3a, b, see Methods) we find that Ey ≃ 5 MV/m along the GT − GSET axis (green arrow in Fig. 1a) at the readout point (Supplementary Information), confirming that we expect rapid spin relaxation for B||[001] and B||[100] where B⊥E (Fig. 2a–c).

Evolution of spin-relaxation rates with electric field. a, b Modelled electrostatic potential and electric field in the nanoelectronic device, showing a dominant field (Ey ≃ 5 MV/m) along GSET − GT. c Electric field dependence of spin-relaxation rates, consistently describing donor qubits in the bulk (Ey = 0) and in nanoelectronic devices (Ey > 0)

Following the same argument, we show that the lifetime-limiting effects of HEB can be eliminated by aligning E||B, such that Beff vanishes. Indeed, at both B||[010] and \(B{\mathrm{||}}[0\bar 10]\) (Fig. 2a–c), we measure T1 = 1.25 s (1/T1 ≃ 0.8 1/s) at B = 3.5 T. This value is an enhancement by a factor ~6–7 compared to previous measurements in nanoelectronic devices5 and identical to spin lifetimes measured in bulk donors along the equivalent B||[001] axis.28 Such consistency in spin-relaxation times for equivalent crystal directions thus give a strong indication that we have reached the bulk limit of donor spin lifetimes within a nanoelectronic device. Given that spin lifetimes as long as 1111 s (18 min) at 1.25 K and B = 0.8 T have been measured in bulk,28 such timescales should be attainable in nanoelectronic devices by careful design of the electromagnetic environment and at low enough magnetic fields.12 A further enhancement of spin-relaxation times beyond the bulk limit may be achieved using single spins confined to donor clusters instead of single donors.19

For an estimate of the respective bulk Rashba SOC and HEB coupling strengths, we can fit the spin-relaxation anisotropy (solid red and blue lines in Figs. 1e and 2a, b, see Supplementary Information for detail), from which we extract R = 9.05 × 10−19e m2 and C = 5.86 × 10−14e m/T (out-of-plane), as well as R = 9.53 × 10−19e m2 and C = 6.01 × 10−14e m/T (in-plane). Not only are the extracted coupling coefficients in remarkable agreement across both measurement cooldowns, we also confirm their theoretically predicted ratio as expressed in Eq. (3). The extracted HEB coupling strength now allows us to to calculate a maximum effective magnetic field strength |Beff| = CEyBz/μB ~ 18.9 mT for Ey = 5 MV/m and B = 3.5 T—more than two orders of magnitude larger than the vanishing bulk Rashba SOC field BR = Rk0mEy/μB ~ 0.1 mT.

The evolution of the spin-relaxation rates with increasing electric field strength Ey from bulk donors (circles) to donors in electric fields (squares) is shown in Fig. 3c. For simplicity, here we have assumed Ex = Ez = 0, consistent with our COMSOL calculations (<1 MV/m), accounting for a small phase shift in θ. As evident from Fig. 3c, our theory describes both donors in zero and finite electric fields, providing a consistent theoretical framework for spin relaxation of donor-bound electrons.

To conclude, we have demonstrated a previously unreported spin–orbit induced magnetoelectric coupling for donor-bound electron spins in silicon. In contrast to bulk donors, we find that this higher-order coupling provides a spin-relaxation pathway, that can dominate spin relaxation for certain orientations of external electric and magnetic fields. By careful alignment of an external vector-magnetic field, we can eliminate the lifetime-limiting effect, thereby recovering the bulk-regime of donor spin relaxation. Thus, we resolve the long-standing puzzle as to the significant differences of spin lifetimes in bulk donors to those in nanoelectronic devices. Given the strength of the observed magnetoelectric coupling—two orders of magnitude larger than bulk Rashba SOC—it should allow for electrically driven spin resonance,32,33,34 not previously thought possible in donors.

Finally, we note that this higher-order coupling could be observable for atomically confined spins in inversion asymmetric semiconductors, particularly when multiple valleys are present. A similar prediction of such magnetoelectric coupling has recently been made for bilayer graphene.35 We thus expect that our discovery will stimulate future theoretical and experimental investigations of spin control via higher-order electromagnetic coupling.

Methods

Device fabrication

The qubit device was patterned7 on the hydrogen-terminated Si(001)–2 × 1 surface of p-doped substrates (NA ≃ 5 × 1015–5 × 1016 cm−3). Following STM-lithography, the template was exposed to PH3 gas followed by annealing (350 °C, 1 min), which dopes the device electrodes to N2D ≃ 2 × 1014 cm−2, allowing quasi-metallic conduction.36 The device was subsequently encapsulated with ~45 nm of epitaxial silicon at low temperature (250 °C), followed by the alignment of Ohmic contacts.7

Electrical measurements

Electron spin-relaxation rates were measured over two separate thermal cycles (cooldowns) in a top-loading Leiden cryo-free three-axis vector field fridge (base temperature ≤25 mK, electron temperature (Tel ≃ 100 mK) and Bz ≤ 9 T, Bx ≤ 5 T, By ≤ 1 T). In a first cooldown, the device was mounted such that Bz||[001], parallel to the surface normal (crystal growth direction) and Bx||[110]. In a second cooldown, the device was mounted such that Bz||[110] and \(B_x{\mathrm{||}}[1\bar 10]\), allowing a rotation of the field vector within the sample plane. Any possible misalignment in either cooldown was estimated no greater than ±5°. Electron spin readout was performed by spin selective tunnelling from the donor to the SET, using a three-level voltage pulse sequence on the G1 and G2 gates, upon monitoring the SET drain current (bandwidth: 3 kHz).

Electrostatic modelling

Electric fields in the device were calculated using the electrostatics module of the finite element solver COMSOL. We assume metallic electrodes with a thickness, t = 2 nm, as previously shown to represent STM-patterned quantum dots.7 The surface of the device was terminated with 2 nm of SiO2, assuming Neumann boundary conditions. Both cooldowns were modelled separately with slightly different gate voltages (out-of-plane: VG1 = VG2 = 400 mV, in-plane: VG1 = VG2 = 150 mV), consistent with the experiment. In both cooldowns VGT = VSET = 900 mV.

Data availability

Supplementary Information is available at npj Quantum Information website. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Loss, D. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum computation with quantum dots. Phys. Rev. A 57, 120 (1998).

Kane, B. E. A silicon-based nuclear spin quantum computer. Nature 393, 133–137 (1998).

Tyryshkin, A. M. et al. Electron spin coherence exceeding seconds in high-purity silicon. Nat. Mater. 11, 143–147 (2012).

Watson, T. F., Weber, B., House, M. G., Büch, H. & Simmons, M. Y. High-fidelity rapid initialization and read-out of an electron spin via the single donor D − charge state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 166806 (2015).

Morello, A. et al. Single-shot readout of an electron spin in silicon. Nature 467, 687–691 (2010).

Pla, J. J. et al. A single-atom electron spin qubit in silicon. Nature 489, 541–545 (2012).

Weber, B. et al. Spin blockade and exchange in Coulomb-confined silicon double quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 430–435 (2014).

Dehollain, J. P. et al. Single-shot readout and relaxation of singlet and triplet states in exchange-coupled 31P electron spins in silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 236801 (2014).

Hollenberg, L. C. L., Greentree, A. D., Fowler, A. G. & Wellard, C. J. Two-dimensional architectures for donor-based quantum computing. Phys. Rev. B 74, 045311 (2006).

Elzerman, J. M. et al. Single-shot read-out of an individual electron spin in a quantum dot. Nature 430, 431–435 (2004).

Scarlino, P. et al. Spin-relaxation anisotropy in a GaAs quantum dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 256802 (2014).

Camenzind, L. C. et al. Hyperfine-phonon spin relaxation in a single-electron gaas quantum dot. Nat. Commun. 9, 3454 (2018).

Ferdous, R. et al. Valley dependent anisotropic spin splitting in silicon quantum dots. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 26 (2018).

Ferdous, R. et al. Interface-induced spin–orbit interaction in silicon quantum dots and prospects for scalability. Phys. Rev. B 97, 241401 (2018).

Zwanenburg, F. A. et al. Silicon quantum electronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 961–1019 (2013).

Hasegawa, H. Spin-lattice relaxation of shallow donor states in Ge and Si through a direct phonon process. Phys. Rev. 118, 1523–1534 (1960).

Roth, L. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory Reports (1960).

Roth, L. M. g-factor and donor spin-lattice relaxation for electrons in germanium and silicon. Phys. Rev. 118, 1534–1540 (1960).

Watson, T. F. et al. Atomically engineered electron spin lifetimes of 30s in silicon. Sci. Adv 3, 1–6 (2017).

Mohiyaddin, F. A. et al. Noninvasive spatial metrology of single-atom devices. Nano Lett. 13, 1903–1909 (2013).

Sellier, H. et al. Transport spectroscopy of a single dopant in a gated silicon nanowire. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 206805 (2006).

Lansbergen, G. P. et al. Gate-induced quantum-confinement transition of a single dopant atom in a silicon finfet. Nat. Phys. 4, 656–661 (2008).

Rahman, R. et al. Electric field reduced charging energies and two-electron bound excited states of single donors in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 84, 115428 (2011).

Rahman, R. et al. Engineered valley–orbit splittings in quantum-confined nanostructures in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 83, 195323 (2011).

Lansbergen, G. P. et al. Lifetime-enhanced transport in silicon due to spin and valley blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 136602 (2011).

Rahman, R. et al. Gate-induced g-factor control and dimensional transition for donors in multivalley semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 155301 (2009).

Bir, G., Butekov, E. & Pikus, G. Spin and combined resonance on acceptor centres in Ge and Si type crystals—I: paramagnetic resonance in strained and unstrained crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 24, 1467–1474 (1963).

Wilson, D. K. & Feher, G. Electron spin resonance experiments on donors in silicon. III. Investigation of excited states by the application of uniaxial stress and their importance in relaxation processes. Phys. Rev. 124, 1068–1083 (1961).

Winkler, R. Spin–Orbit Coupling Effects in Two-Dimensional Electron and Hole Systems. Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg (2003).

Salfi, J., Mol, J. A., Culcer, D. & Rogge, S. Charge-insensitive single-atom spin–orbit qubit in silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 246801 (2016).

Hanson, R., Kouwenhoven, L. P., Petta, J. R., Tarucha, S. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Spins in few-electron quantum dots. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 1217 (2007).

Nowack, K. C., Koppens, F. H. L., Nazarov, Y. V. & Vandersypen, L. M. K. Coherent control of a single electron spin with electric fields. Science 318, 1430 (2007).

Corna, A. et al. Electrically driven electron spin resonance mediated by spin–valley–orbit coupling in a silicon quantum dot. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 6 (2018).

Jock, R. M. et al. A silicon metal–oxide–semiconductor electron spin–orbit qubit. Nat. Commun. 9, 1768 (2018).

Winkler, R. & Zülicke, U. Electromagnetic coupling of spins and pseudospins in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 91, 205312 (2015).

Weber, B. & Simmons, M. Y. Determining the quantum-coherent to semiclassical transition in atomic-scale quasi-one-dimensional metals. Phys. Rev. B 94, 081412 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Mahapatra for useful discussions. The device was fabricated in part at the New South Wales node of the Australian National Fabrication Facility. This research was conducted by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Quantum Computation and Communication Technology (project number CE110001027), the US National Security Agency and the US Army Research Office under contract number W911NF-17-1-1-0202, and the ARC Discovery Project scheme. BW acknowledges an ARC DECRA fellowship (project number DE160101334) and a Singapore National Research Foundation (NRF) Fellowship (NRF-NRFF2017-11). M.Y.S. acknowledges an ARC Laureate Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.W. and T.F.W. prepared the sample, performed the measurements, and analysed the data. R.L. and A.R.H. assisted with the vector fridge measurement. Y.H., R.R., and L.C.L.H. developed the theory. B.W. planned the experiment. M.Y.S. supervised the project. B.W. and M.Y.S. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weber, B., Hsueh, YL., Watson, T.F. et al. Spin–orbit coupling in silicon for electrons bound to donors. npj Quantum Inf 4, 61 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0111-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0111-1

This article is cited by

-

Optimisation of electron spin qubits in electrically driven multi-donor quantum dots

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Review of performance metrics of spin qubits in gated semiconducting nanostructures

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

-

Topological phases of a dimerized Fermi–Hubbard model for semiconductor nano-lattices

npj Quantum Information (2020)

-

The sub-band structure of atomically sharp dopant profiles in silicon

npj Quantum Materials (2020)

-

Gate-reflectometry dispersive readout and coherent control of a spin qubit in silicon

Nature Communications (2019)