Abstract

Surface codes are building blocks of quantum computing platforms based on 2D arrays of qubits responsible for detecting and correcting errors. The error suppression achieved by the surface code is usually estimated by simulating toy noise models describing random Pauli errors. However, Pauli noise models fail to capture coherent processes such as systematic unitary errors caused by imperfect control pulses. Here we report the first large-scale simulation of quantum error correction protocols based on the surface code in the presence of coherent noise. We observe that the standard Pauli approximation provides an accurate estimate of the error threshold but underestimates the logical error rate in the sub-threshold regime. We find that for large code size the logical-level noise is well approximated by random Pauli errors even though the physical-level noise is coherent. Our work demonstrates that coherent effects do not significantly change the error correcting threshold of surface codes. This gives more confidence in the viability of the fault-tolerance architecture pursued by several experimental groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed major progress towards the demonstration of quantum error correction and reliable logical qubits.1,2,3,4,5,6 Such qubits can be protected from noise by measuring syndromes of suitable parity check operators and applying syndrome-dependent recovery operations. Topological quantum codes such as the surface code7,8 are among the most attractive candidates for an experimental realization, as they can be implemented on a two-dimensional grid of qubits with local check operators.

It is believed that such codes can tolerate a high level of noise9,10,11 which is comparable to what can be achieved in the latest experiments.6 The general confidence in the noise-resilience of topological codes primarily rests on considerations of Pauli noise—a simplified noise model where errors are Pauli operators X,Y,Z drawn at random from some distribution. An example is the case where each qubit j experiences noise described by the channel

with suitable probabilities \(\varepsilon _j^x,\varepsilon _j^y,\varepsilon _j^z\) and \(\varepsilon _j = 1 - \varepsilon _j^x - \varepsilon _j^y - \varepsilon _j^z\). This kind of noise can be fully described by the stabilizer formalism.12 In pioneering work, Dennis et al.9 exploited this algebraic structure to establish the first analytical threshold estimates, see also.13 The effect of Pauli noise also is efficiently simulable thanks to the Gottesman-Knill theorem, providing numerical evidence for high error thresholds of topological codes.14 The efficient simulability property has recently been extended beyond Pauli noise to random Cliffords and Pauli-type projectors.15

While such algebraically defined noise models are attractive from a theoretical viewpoint, they often do not correspond to noise encountered in real-world setups. They are—in a sense—not quantum enough: they model probabilistic processes where errors act randomly on subsets of qubits. Rather than being of such a probabilistic (or incoherent) nature, noise in a realistic device will often be coherent, i.e., unitary, and can involve small rotations acting everywhere. A typical situation where this arises is if e.g., frequencies of oscillator qubits are misaligned: this results in systematic unitary over- or under-rotations. On a single-qubit level, this means that (1) should be replaced by noise of the form

with a suitable unitary operator Uj∈SU(2). Since such errors generally cannot be described within the stabilizer formalism, understanding their effect on a given quantum fault-tolerant scheme is a challenging problem.

Prior theoretical work indicates that the difference between coherent and incoherent errors could be significant. In particular, it was observed16,17,18,19,20 that coherent errors can lead to large differences between average-case and worst case fidelity measures suggesting that a critical reassessment of commonly used benchmarking measures is necessary. This observation motivates the question of how much coherence is present in the effective logical-level noise21,22 experienced by encoded qubits. Depending on whether or not the logical noise is coherent one may choose different metrics for quantifying performance of a given fault-tolerant scheme. Significant progress has been made towards understanding the structure of the logical noise for concatenated codes.21,22,23 However, these studies are not directly applicable to large topological codes such as those considered here.

Brute-force simulations of coherent noise in small codes were presented in24,25,26,27 for Steane codes and surface codes with up to 17 qubits. Simulating coherent errors by brute force clearly requires time (and memory) exponential in the number of qubits n. For the surface code, Darmawan and Poulin28,29 proposed an algorithm with a runtime exponential in n1/2 based on tensor networks, and simulated systems with up to 153 qubits. This algorithm can handle arbitrary noise (including, e.g., amplitude damping). Unfortunately, its formidable complexity prevents accurate estimation of error thresholds, e.g., for the systematic rotations considered here. In,30 threshold estimates for the 1D repetition code were obtained. To our knowledge, there are no analogous threshold estimates for topological codes subject to coherent noise.

Results

Coherent noise and quantum memory

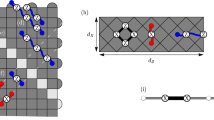

We shall consider a particular version of the surface code proposed in Refs.31,32 A distance-d surface code has one logical qubit and n = d2 physical qubits located at sites of a square lattice of size d × d with open boundary conditions, see Fig. 1.

Surface codes with distance d = 3 and d = 5. Qubits and stabilizers are located at sites and faces respectively. A stabilizer Bf located on a face f applies X (black faces) or Z (white faces) to each qubit on the boundary of f. Logical Pauli operators XL (red) and ZL (blue) have support on the left and the top boundary

We consider the situation where a logical state ψL initially encoded by the surface code undergoes a coherent error U = U1⊗…⊗Un which applies some (unknown) unitary operator Uj to each qubit j. To diagnose and correct the error without disturbing the encoded state we assume the standard protocol based on the syndrome measurement is applied. It works by measuring the eigenvalue (syndrome) sf = ±1 of each stabilizer Bf on the corrupted state U|ψL〉 and then applying a Pauli-type correction operator Cs depending on the measured syndrome s = {sf}f. The correction Cs is computed by a classical decoding algorithm (for example, one may choose Cs as a minimum-weight Pauli error consistent with s). We note that the syndrome s is a random variable with some probability distribution p(s) since the error U maps the initial logical state to a coherent superposition of states with different syndromes. We only consider noiseless syndrome measurements, and also assume that the correction operations Cs can be executed noiselessly. These assumptions (which can be relaxed by adapting our methods) are motivated by our focus on the effect of coherent errors. They also imply that we can assume that the correction Cs always returns the system to the logical subspace resulting in some final logical state |ϕs〉. Thus the process of (noisy) storage with error U and subsequent error correction maps an initial encoded state |ψL〉 to a certain final logical state |ϕs〉 with probability p(s), while also providing the classical syndrome s.

The main question addressed here is how close the final state |ϕs〉 and the initial state |ψL〉 are as a function of the noise. Here we will assume that the error applied to qubit j is of the form Uj = exp(iηjZ) for some (unknown) angle ηj. The restriction to Z-rotations is dictated by the limitations of our simulation algorithm for storage. It provides a paradigmatic example of coherent noise. We also discuss a related problem—that of state preparation—and provide analogous results for general SU(2) coherent errors (see Supplementary Note 2).

Effective coherent logical noise

We show analytically that the syndrome probability distribution p(s) is independent of the initial logical state ψL whereas the final logical state has the form

for some logical rotation angle θs∈[0, π) depending on the syndrome s (see Supplementary Note 1). In other words, the error correction process converts physical-level coherent noise U to effective coherent noise exp(iθsZL) on the logical qubit, with a strength θs depending on the (randomly distributed) syndrome s.

The parametrization (3) concisely captures the effect of coherent noise, providing us with a window into the nature of this conversion. We use the quantity

as a measure of the (average) logical error rate: this is the average (over syndromes) diamond-norm distance33 \(\left\| {\Lambda _s - {\mathrm{id}}} \right\|_\diamondsuit = 2\left| {{\mathrm{sin}}\theta _s} \right|\) between the conditional logical channel

and the identity channel id. While the quantity PL provides a meaningful measure for how well the initial state is preserved, the full information of the structure of residual logical errors is given by the distribution p(s) over logical rotation angles θs.

Polynomial-time classical simulation

We construct a polynomial-time classical algorithm which takes as input |ψL〉 and the rotation angles η1,…,ηn, samples a syndrome s from the distribution p(s), and outputs s as well as the associated final state |ϕs〉 (i.e., the logical rotation angle θs). The runtime of this algorithm scales as O(n2), where we measure complexity in terms of the number of additions, multiplications, and divisions of complex numbers that are required. Strictly speaking, the simulation time scales as O(n2) + t(n), where t(n) is the runtime of the decoding algorithm that computes the correction Cs. In our simulations the decoding time was negligible compared with the time required to sample the syndrome and compute the final logical state. By sampling sufficiently many syndromes, one can thus learn how frequently and in which ways error correction may fail in the presence of coherent noise. In particular, we may estimate the quantity PL. By providing both the syndrome s and the the logical rotation angle θs conditioned on s, our algorithm also gives us a unique opportunity to investigate the full structure of the logical-level noise.

Numerical results

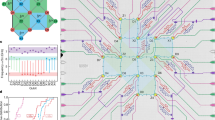

Using our algorithm, we perform the first numerical study of large topological codes subject to coherent noise, performing simulations for surface codes with up to n = 2401 physical qubits, see Table 1 for a timing analysis.

This shows that efficient classical simulation of fault-tolerance processes under coherent noise is possible, and allows us to extract key characteristics of these codes in the limit of large system size.

In more detail, in our simulations we consider translation-invariant coherent noise of the form (eiθZ)⊗n, where θ∈[0, π) is the only noise parameter. The Pauli correction Cs was computed using the standard minimum weight matching decoder9,34 with constant weights independent of θ.

Our numerical results for the logical error rate PL are presented in Fig. 2. Using the symmetries of the surface code one can easily check that PL is invariant under flipping the sign of θ; accordingly, it suffices to simulate θ ≥ 0. The data suggests that the quantity PL decays exponentially in the code distance d for θ<θ0, where

can be viewed as an error correction threshold. We observe the exponential decay of PL as a function of the code distance d in the sub-threshold regime.

(Empirical) logical error rate PL for storage of quantum states. We consider distance-d surface codes subject to coherent errors exp(iθZ) on each qubit. We consider surface codes with distance 5 ≤ d ≤ 37. The smallest distance d = 3 was skipped because of strong finite-size effects (note that the considered surface codes are only defined for odd values of d). In all figures, the logical error rate PL was estimated by the Monte Carlo method with at least 50,000 syndrome samples per data point

Surprisingly, the threshold estimate Eq. (6) agrees very well with the so-called Pauli twirl approximation35,36 where coherent noise of the form \({\cal N}(\rho ) = e^{i\theta Z}\rho e^{ - i\theta Z}\) is replaced by its Pauli-twirled version, i.e., dephasing noise of the form \({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}(\rho ) = (1 - \varepsilon )\rho + \varepsilon Z\rho Z\) with \(\varepsilon = {\mathrm{sin}}^2\theta\). For the latter the threshold error rate is around ε0 ≈ 0.11, see Ref.9 Solving the equation \(\varepsilon _0 = \mathop {{sin}}\nolimits^2 (\theta _0)\) for θ0 yields θ0 ≈ 0.10π, in agreement with Eq. (6).

Applying the Pauli twirl at the physical level amounts to ignoring the coherent part of the noise. To assess the validity of this approximation, let us compare logical error rates \(P^L\) computed for coherent physical noise \({\cal N}\) and its Pauli-twirled version \({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}\). Let \(P^L({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}})\) be the logical error rate corresponding to \({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}\). The plot of \(P^L({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}})\) and the ratio \(P^L/P^L({\cal N}_{{\mathrm{twirl}}})\) are shown on Fig. 3. It can be seen that applying the Pauli twirl approximation to the physical noise gives an accurate estimate of the error threshold but significantly underestimates the logical error probability in the sub-threshold regime. We conclude that coherence of noise has a profound effect on the performance of large surface codes in the sub-threshold regime which is particularly important for quantum fault-tolerance. This phenomenon was previously observed in,23,28 but has not been studied for large topological codes prior to our work.

Comparison between the logical error rates PL and PL(Ntwirl) computed for coherent noise N(ρ) = eiθZρe−iθZ and its Pauli twirled version Ntwirl(ρ) = (1 − ε)ρ + εZρZ with \(\varepsilon = {\mathrm{sin}}^2(\theta )\). In both cases we used the minimum weight matching decoder. The plot demonstrates that applying the Pauli twirl approximation to the physical noise significantly underestimates the logical error rate in the sub-threshold regime

More information about the structure of the effective noise can be gained from Fig. 4, which shows the empirical probability distribution of the logical rotation angle θs obtained by sampling 106 syndromes s for the physical Z-rotation angle θ = 0.08π (which we expect to be slightly below the threshold). We compare the cases d = 9 and 25. In both cases the distribution has a sharp peak at θs = 0 (equivalent to θs = π). This peak indicates that error correction almost always succeeds in the considered regime. It can be seen that increasing the code distance has a dramatic effect on the distribution of θs. The distance-9 code has a broad distribution of θs meaning that the logical-level noise retains a strong coherence. On the other hand, the distance-25 code has a sharply peaked distribution of θs with a peak at θs = π/2 which corresponds to the logical Pauli error ZL. Such errors are likely to be caused by “ambiguous” syndromes s for which the minimum weight matching decoder makes a wrong choice of the Pauli correction Cs. We conclude that as the code distance increases, the logical-level noise can be well approximated by random Pauli errors even though the physical-level noise is coherent.

These histograms show the empirical probability distribution of logical rotation angles θs for the code distance d = 9 (left) and d = 25 (right) obtained by sampling 106 syndromes s. The histograms use the same noise parameter θ = 0.08π. For ease of visualization, we truncated the main peak at θs = 0

To get a deeper insight into this phenomenon, we introduce and numerically study associated measures of “incoherence”. To define a metric quantifying the degree of coherence present in the logical-level noise, let us consider the twirled version of the logical channel Λs,

and the corresponding logical error rate

Comparison of Eqs. (4,7) reveals that \(P^L \ge P_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}^L\) with equality iff the distribution of θs has all its weight on {0,π/2}, that is, when the logical noise is incoherent. It is therefore natural to measure coherence of the logical noise by the ratio \(P^L/P_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}^L\). This “coherence ratio” is plotted as a function of θ on Fig. 5(a). The data indicates that the coherence ratio decreases for increasing system size approaching one for large code distances. This further supports the conclusion that the logical noise has a negligible coherence. Finally, in Fig. 5(b), we show the analogous quantity for the average logical noise channel21 defined as \({\mathrm{\Lambda }} = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_s p(s){\mathrm{\Lambda }}_s\). This average channel provides an appropriate model for the logical-level noise if the environment has no access to the measured syndrome. This may be relevant, for instance, in the quantum communication settings where noise acts only during transmission of information. Thus one can alternatively define the coherence ratio as

where Λtwirl is the Pauli-twirled version of Λ. A straightforward computation gives \(P^L/P_{{\mathrm{twirl}}}^L = \frac{{\sqrt {\varepsilon ^2 + \delta ^2} }}{\varepsilon }\) where \(\varepsilon = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_s p(s){\mathrm{sin}}^2(\theta _s)\) and \(\delta = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_s p(s){\mathrm{sin}}(2\theta _s)/2\). The coherence ratio of the average logical channel is plotted as a function θ on Fig. 5(b). It provides particularly strong evidence that in the limit of large code distances, coherent physical noise gets converted into incoherent logical noise.

Discussion

Our work extends the range of noise models efficiently simulable on a classical computer. It allows—for the first time—to numerically investigate the effect of coherent errors in the regime of large code sizes which is important for reliable error threshold estimates. Our simulation algorithms make no assumptions about the particular decoder used. Hence the proposed approach should be universally applicable to benchmarking the performance of different fault-tolerance strategies in the presence of coherent noise. Although we simulated only translation-invariant noise models, all our algorithms apply to more general qubit-dependent noise. This enables numerical study of recently proposed state injection protocols,37 e.g., preparation of logical magic states, in the presence of coherent errors. Another possible application could be testing the so-called disorder assisted error correction method38,39,40 where artificial randomness introduced in the code parameters suppresses coherent propagation of errors due to the Anderson localization phenomenon. We leave as an open problem whether our algorithm can be extended to more general codes, such as as color and hyperbolic codes, as well as more general noise models such as those including systematic cross-talk errors.

Our numerical results spell good news for quantum engineers pursuing surface code realizations: thresholds for state preparation and storage are reasonably high, suggesting that coherent noise is not as detrimental as one could expect from the previous studies. The numerical investigation of the logical-level noise gives rise to a conceptually appealing conjecture: error correction converts coherent physical noise to incoherent logical noise (for large code sizes). Whether this is an artifact of the considered error correction scheme or manifestation of a more general phenomenon is an interesting open question.

Methods

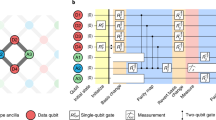

Our algorithm is based on a fermionic representation of the surface code proposed by Kitaev41 and Wen,31 see Fig. 6. It works by encoding each qubit of the surface code into four Majorana fermions in a way that simplifies the structure of the surface code stabilizers. The Kitaev-Wen representation has previously been used by Terhal et al.42 to design fermionic Hamiltonians with topologically ordered ground states. Here we show that this representation is also well-suited for the design of efficient simulation algorithms.

A fermionic representation of the distance-3 surface code. Solid circles represent paired (blue) and unpaired (red) Majorana modes. The pattern extends to larger codes in a translation invariant fashion. An edge e oriented from cp to cq defines a link operator Le = icpcq. On a subspace defined by local constraints, stabilizers of the surface code can be represented as products of link operators

The fermionic version of the surface code is described by Majorana operators c1,…,c4n that obey the standard commutation rules \(c_p^\dagger = c_p\), \(c_p^2 = I\), and cpcq = −cqcp for p ≠ q. Each vertex u of the surface code lattice contains a copy of a simple Majorana fermion code41 with four Majorana modes, a single logical qubit, and a stabilizer Su = ±cpcqcrcs. It has logical Pauli operators \(\overline X _u = ic_pc_q\) and \(\overline Z _u = ic_qc_r\). We call this Majorana code the C4-encoding of a qubit. Each Pauli operator P has a fermionic counterpart \(\overline P\) obtained by applying the C4-encoding independently to each qubit of P.

The first step towards the construction of our algorithm is to translate notions from the surface code to the fermionic setting (see Supplementary Note 1). For example, we find that the fermionic counterpart \(\overline B _f\) of a surface code stabilizer Bf associated with a face f can be expressed as a product

of link operators (see Fig. 6) associated with edges bordering f. This implies that the syndrome measurement may effectively be replaced by the measurement of the commuting link operators by taking the product of the corresponding measurement outcomes. Similarly, we find that the logical operators XL and ZL (see Fig. 1) have fermionic counterparts of the form

for suitably chosen subsets LEFT and TOP of edges. Given the eigenvalues of the link operators, we may thus use these identities to compute final logical states from expectation values of the unpaired modes. Finally, as the problem of simulating storage requires considering arbitrary surface code states, we need to identify fermionic version \(|\bar \psi _L\rangle\) of an encoded (logical) state \(\psi \in {\Bbb C}^2\). This takes the form

where \(\bar \psi\) is a C4-encoded version of ψ on the unpaired modes, and ϕlink is the unique state of 4n−4 Majoranas stabilized by all link operators. Eq. (11) implies that we may replace the initial logical state by a simpler state at the expense of measuring additional stabilizers.

Using these relationships, we show (see Supplementary Notes 2 and 3) that the error correction protocols considered in this paper can be decomposed into a sequence of O(n) elementary gates from a gate set known as a fermionic linear optics (FLO), see Refs.43,44 It includes the following operations:

-

1.

Initialize a pair of Majorana modes p,q in a basis state |0〉 satisfying icpcq|0〉 = |0〉.

-

2.

Apply the unitary operator U = exp(γcpcq). Here γ∈[0, π) is a rotation angle.

-

3.

Apply the projector Λ = (I + icpcq)/2. Compute the norm of the resulting state.

It is well-known that quantum circuits composed of FLO gates can be efficiently simulated classically.43,44,45,46 The simulation runtime scales as O(n) for gates of type (1,2) and as O(n2) for gates of type (3). By exploiting the geometrically local structure of the surface code we are able to reduce the number of modes such that at any given time step the simulator only needs to keep track of O(n1/2) modes. Accordingly, each FLO gate can be simulated in time at most O(n). Since the total number of gates is O(n), the total simulation time scales as O(n2).

Code availability

The code used in this study is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Data availability

Data used in this study is available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Reed, M. D. et al. Realization of three-qubit quantum error correction with superconducting circuits. Nature 482, 382 (2012).

Barends, R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500–503 (2014).

Kelly, J. et al. State preservation by repetitive error detection in a superconducting quantum circuit. Nature 519, 66–69 (2015).

Corcoles, A. et al. Demonstration of a quantum error detection code using a square lattice of four superconducting qubits. Nat. Communications 6, 6979 (2015).

Ofek, N. et al. Demonstrating quantum error correction that extends the lifetime of quantum information. arXiv. 1602, 04768 (2016).

Takita, M. et al. Demonstration of weight-four parity measurements in the surface code architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 210505 (2016).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Bravyi, S. B. & Kitaev, A. Y. Quantum codes on a lattice with boundary, arXiv:quant-ph/9811052 (1998).

Dennis, E., Kitaev, A., Landahl, A. & Preskill, J. Topological quantum memory. J. Math. Phys. 43, 4452–4505 (2002).

Raussendorf, R. & Harrington, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation with high threshold in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 190504 (2007).

Fowler, A. G., Stephens, A. M. & Groszkowski, P. High-threshold universal quantum computation on the surface code. Phys. Rev. A 80, 052312 (2009).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer Codes and Quantum Error Correction. PhD thesis, California Inst. Technol. (1997).

Fowler, A. G. Proof of finite surface code threshold for matching. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 180502 (2012).

Wang, D. S., Fowler, A. G. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. Surface code quantum computing with error rates over. Phys. Rev. A 83, 020302 (2011).

Gutierrez, M., Svec, L., Vargo, A. & Brown, K. R. Approximation of realistic errors by Clifford channels and Pauli measurements. Phys. Rev. A 87, 030302 (2013).

Sanders, Y. R., Wallman, J. J. & Sanders, B. C. Bounding quantum gate error rate based on reported average fidelity. New J. Phys. 18, 012002 (2016).

Kueng, R., Long, D. M., Doherty, A. C. & Flammia, S. T. Comparing experiments to the fault-tolerance threshold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 170502 (2016).

Wallman, J., Granade, C., Harper, R. & Flammia, S. T. Estimating the coherence of noise. New J. Phys. 17, 113020 (2015).

Puzzuoli, D. et al. Tractable simulation of error correction with honest approximations to realistic fault models. Phys. Rev. A 89, 022306 (2014).

Magesan, E., Puzzuoli, D., Granade, C. E. & Cory, D. G. Modeling quantum noise for efficient testing of fault-tolerant circuits. Phys. Rev. A 87, 012324 (2013).

Rahn, B., Doherty, A. C. & Mabuchi, H. Exact performance of concatenated quantum codes. Phys. Rev. A 66, 032304 (2002).

Fern, J., Kempe, J., Simic, S. N. & Sastry, S. Generalized performance of concatenated quantum codes—a dynamical systems approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 51, 448–459 (2006).

Greenbaum, D. & Dutton, Z. Modeling coherent errors in quantum error correction. Quantum Science and Technology 3, 015007 (2017).

Li, M., Gutirrez, M., David, S. E., Hernandez, A. & Brown, K. R. Fault tolerance with bare ancillae for a [[7,1,3]] code. Phys. Rev. A 96, 032341 (2017).

Tomita, Y. & Svore, K. M. Low-distance surface codes under realistic quantum noise. Phys. Rev. A 90, 062320 (2014).

Barnes, J. P., Trout, C. J., Lucarelli, D. & Clader, B. D. Quantum error-correction failure distributions: Comparison of coherent and stochastic error models. Phys. Rev. A 95, 062338 (2017).

Chamberland, C., Wallman, J., Beale, S. & Laflamme, R. Hard decoding algorithm for optimizing thresholds under general markovian noise. Phys. Rev. A95, 042332 (2017).

Darmawan, A. S. & Poulin, D. Tensor-network simulations of the surface code under realistic noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 040502 (2017).

Darmawan, A. & Poulin, D. An efficient general decoding algorithm for the surface code. Phys. Rev. E 97, 051302 (2018).

Suzuki, Y., Fujii, K. & Koashi, M. Efficient simulation of quantum error correction under coherent error based on non-unitary free-fermionic formalism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 190503 (2017).

Wen, X.-G. Quantum orders in an exact soluble model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 016803 (2003).

Bombin, H. & Martin-Delgado, M. A. Optimal resources for topological two-dimensional stabilizer codes: Comparative study. Phys. Rev. A 76, 012305 (2007).

Yu Kitaev, A. Quantum computations: algorithms and error correction. Russ. Math. Surv. 52, 1191–1249 (1997).

Fowler, A. G., Whiteside, A. C. & Hollenberg, L. C. L. Towards practical classical processing for the surface code. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 180501 (2012).

Emerson, J. et al. Symmetrized characterization of noisy quantum processes. Science 317, 1893–1896 (2007).

Silva, M., Magesan, E., Kribs, D. W. & Emerson, J. Scalable protocol for identification of correctable codes. Phys. Rev. A 78, 012347 (2008).

Lodyga, J., Mazurek, P., Grudka, A. & Horodecki, M. Simple scheme for encoding and decoding a qubit in unknown state for various topological codes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8975 (2015).

Wootton, J. R. & Pachos, J. K. Bringing order through disorder: localization of errors in topological quantum memories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 030503 (2011).

Stark, C., Pollet, L., Imamoglu, A. & Renner, R. Localization of toric code defects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 030504 (2011).

Bravyi, S. & König, R. Disorder-assisted error correction in Majorana chains. Commun. Math. Phys. 316, 641–692 (2012).

Kitaev, A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006).

Terhal, B. M., Hassler, F. & DiVincenzo, D. P. From Majorana fermions to topological order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 260504 (2012).

Knill, E. Fermionic linear optics and matchgates. arXiv:quant-ph/0108033 (2001).

Bravyi, S. Lagrangian representation for fermionic linear optics. Quant. Inf. Comp. 5, 216–238 (2004).

Terhal, B. M. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Classical simulation of noninteracting-fermion quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. A 65, 032325 (2002).

Bravyi, S. & Koenig, R. Classical simulation of dissipative fermionic linear optics. Quant. Inf. Comp. 12, 925 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Flammia, Jay Gambetta, and David Gosset for helpful discussions. RK is supported by the Technical University of Munich—Institute for Advanced Study, funded by the German Excellence Initiative and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 291763. He acknowledges support by the German Federal Ministry of Education through the funding program Photonics Research Germany, contract no. 13N14776 (QCDA-QuantERA) and partial support by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF PHY-1125915, and thanks the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics for their hospitality. NP acknowledges support by TUM-PREP. SB acknowledges support from the IBM Research Frontiers Institute and from Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) under contract W911NF-16-0114.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B., M.E., and R.K. undertook preliminary studies. S.B. and R.K. conceived the simulation algorithms. N.P., together with M.E. and R.K., implemented and tested the state preparation algorithm. S.B. implemented the storage simulation algorithm and collected and analyzed data. The manuscript was prepared by S.B. and R.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bravyi, S., Englbrecht, M., König, R. et al. Correcting coherent errors with surface codes. npj Quantum Inf 4, 55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0106-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0106-y

This article is cited by

-

Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays

Nature (2024)

-

Boundaries of quantum supremacy via random circuit sampling

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Benchmarking universal quantum gates via channel spectrum

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Error statistics and scalability of quantum error mitigation formulas

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Benchmarking quantum logic operations relative to thresholds for fault tolerance

npj Quantum Information (2023)