Abstract

A major outstanding problem for many quantum clock synchronization protocols is the hidden assumption of a common phase reference between the parties to be synchronized. In general, the definition of the quantum states between two parties do not have consistent phase definitions, which can lead to an unknown systematic error. We show that despite prior arguments to the contrary, it is possible to remove this unknown phase via entanglement purification. This closes the loophole for entanglement based quantum clock synchronization protocols, which is a non-local approach to synchronize two clocks independent of the properties of the intervening medium. Starting with noisy Bell pairs, we show that the scheme produces a singlet state for any combination of (i) differing basis conventions for Alice and Bob; (ii) an overall time offset in the execution of the purification algorithm; and (iii) the presence of a noisy channel. Error estimates reveal that better performance than existing classical Einstein synchronization protocols should be achievable using current technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to a universally agreed global standard time is of great importance to many technologies such as data transfer networks, financial trading, airport traffic control, rail transportation networks, telecommunication networks, the global positioning system (GPS), and long baseline interferometry.1 To achieve this, clock synchronization is a fundamental task in such that a network of clocks with a global standard time can be established. Classically, when special relativity is taken into account, there are two basic methods to synchronize clocks: Einstein synchronization2 and Eddington’s slow clock transport.3 In view of the superb stabilities that the next generation of atomic clocks are achieving,4 the question of how best to synchronize clocks with high precision is one that must be addressed. To address this demand, methods based on both ideas have been proposed for the accurate synchronization of clocks: time transfer laser links for the Einstein protocol,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and quantum adaptations of Eddington’s protocol.12,13,14,15 A third method of clock synchronization, based on quantum entanglement, was proposed by Jozsa and co-workers.16 It uses shared prior entanglement between two clocks located at different spatial locations for synchronization. The primary distinguishing feature of entanglement based clock synchronization is that it is based on a non-local resource. In all classical schemes either light or matter is exchanged between the two parties, which makes it susceptible to the properties of the intervening medium (e.g., the atmosphere). By using entanglement, this can be bypassed, making it fundamentally robust way of synchronizing clocks. The original two party synchronization protocol16,17,18,19 has been extended to multi-parties.20,21,22,23 Several experimental verifications of the protocol have been reported.10,13,24,25

One major outstanding issue with many quantum clock synchronization (QCS) protocols is that they implicitly assume a common phase reference.14,17,26 The origin of this problem is that definitions of superposition states of qubits such as \(\left( {\left| 0 \right\rangle + \left| 1 \right\rangle } \right){\mathrm{/}}\sqrt 2\) are defined only up to a phase convention that is defined locally. Establishing a common phase reference is equivalent to already having synchronized clocks, defeating the purpose of the QCS protocol. Worse still, any quantum algorithm that Alice and Bob execute may require careful synchronization in order to not introduce additional phases due to precession of the qubits. This problem affects both quantum versions of Eddington and entanglement based schemes.14,17,26 Proposals to overcome this issue have been proposed for Eddington schemes have been introduced, which require a two-way exchange of clock qubits.14 This however involves sending clock qubit atoms (e.g., Cs, Rb, Sr) between the two parties, which is highly challenging for long-distance intercontinental or space-based communications. In view of photonic long-distance space-based entanglement distribution now being demonstrated,27,28 and the rapid development of quantum memories,29,30 a protocol compatible with this technology is an attractive prospect. For example, long-distance entanglement could be first generated using photons, then stored on qubits where the clocks are present, then the QCS protocol of ref.16 can be executed. We henceforth refer to the scheme of ref.16 when discussing “QCS”.

We show in this paper, contrary to previous arguments26, that it is possible to produce an entangled state with controlled phase without Alice and Bob having any knowledge of each other’s phase definitions as shown in Fig. 1. The main observation is that the full distillation protocol as originally given by Bennett and co-workers31,32 ensures that a controlled entangled state can be produced. The important ingredient in the distillation protocol is the random bilateral rotations, which leaves the singlet state invariant. The ability of the random bilateral rotations to isolate the singlet state—and only the singlet state—allows for a controlled entangled state to be produced in the local basis. This overcomes the necessity of a common phase reference, which is the major criticism made in ref.26. Once this is prepared, it is possible to execute the original QCS protocol of ref.,16 despite the presence of additional phases, differing basis conventions, and noise. We assume that Alice and Bob do have clocks ticking at the correct frequency, such that they can keep track of the precession for the duration of the algorithm, but the clocks have in general a relative time offset (the clocks are syntonized but not synchronized).18 The combination of the entanglement purification and the QCS allows for a completely asynchronous synchronization protocol for clocks, completing the scheme of ref.16.

The situation considered for asynchronous quantum clock synchronization. Charlie distributes entangled singlet states to Alice and Bob, in his basis convention. The entangled states are susceptible to noise, and become mixed on arrival at Alice and Bob’s locations. Alice and Bob have unsynchronized clocks, and also have different basis conventions for the coherent superpositions of the logical states \(\left| 0 \right\rangle\) and \(\left| 1 \right\rangle\). By purifying many entangled qubits, the aim is to synchronize Alice and Bob’s clocks

Results

State purification using quantum circuit argument

Suppose the singlet state

is prepared and sent by Charlie to Alice and Bob. Here the definitions of the states are with respect to Charlie’s basis convention, which may be different to Alice and Bob’s. Thus the state \(\left| 0 \right\rangle _A^{(C)}\) means a qubit state in Alice’s possession, in the basis convention of Charlie, and so on. We assume that Alice, Bob, and Charlie all have different basis conventions, which we can relate according to \(\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(A)}\) = \(e^{ - i\theta _\sigma ^{(A)}}\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(C)}\), \(\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(B)}\) = \(e^{ - i\theta _\sigma ^{(B)}}\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(C)}\), where σ ∈ {0, 1}. If the bases are transformed consistently using the same convention globally, then the state (1) is invariant, for example

where we chose the irrelevant global phase \(\theta _0^{(B)} + \theta _1^{(B)}\) = 0 for simplicity. However, as pointed out by ref.26, without the availability of synchronized clocks, it is not possible for Alice and Bob to know about their mutual basis conventions. Thus the appropriate basis to view the state is in Alice and Bob’s respective local bases

We emphasize that \(\left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{({\mathrm{loc}})}\) = \(\left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{(B)}\) = \(\left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{(C)}\) are all in fact the same state, but they appear different due to different phase conventions. The effect of Alice and Bob choosing different phase conventions is equivalent to having an unknown relative phase in the singlet14,26. We may define the relative difference between the basis choices of Alice and Bob by defining a rotation operator \(U^{(AB)}\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(B)}\) = \(\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(A)}\), \(U^{(BA)}\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(A)}\) = \(\left| \sigma \right\rangle ^{(B)}\) which in this case is \(U^{(AB)}\) = \(U^{(BA)\dagger }\) = \(e^{i\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_\sigma {\kern 1pt} \left( {\theta _\sigma ^{(B)} - \theta _\sigma ^{(A)}} \right)\left| \sigma \right\rangle \left\langle \sigma \right|}\). Operators then transform as

and similarly for Bob’s operators.

In addition to the different phase conventions, when Alice and Bob perform their entanglement purification circuit, they will not know precisely when the other starts their first quantum operation. Due to the precession of the qubits, there will be an additional phase offset in the singlet state, which without loss of generality we can attribute to Alice’s side. Hence the arriving singlet will have a form in the local basis (up to a global phase)

where the time delay operator is

φ = \(\theta _0^{(A)} + \theta _1^{(B)} - \theta _1^{(A)} - \theta _0^{(B)}\) − ωδt, and δt is the time difference between Alice and Bob’s first quantum operation.

Furthermore, in addition to the systematic error introduced by the different phase conventions and time offset, there may be a stochastic error which reduces the purity of the state. We model this process using the noisy channel with both bit and phase flips, which for our state will appear as

where p is the probability that error will be introduced on sending the qubit through a noisy channel to Alice and Bob, and I is the 4 × 4 identity matrix. We assume that N imperfect Bell pairs (7) are shared between Alice and Bob, and φ is unknown to both of them. The task is then to achieve clock synchronization by first purifying the above state to a sufficiently high fidelity, then executing the QCS protocol without knowledge of any shared timing information.

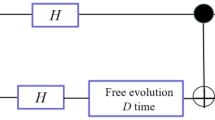

We first argue, using quantum circuit methods, that it is possible to perform entanglement purification such that a singlet state is obtained in the local basis. In the originally conceived form of entanglement purification31,32, the bilateral random unitary rotations and the Bell state comparison are performed synchronously, and also using the same basis convention throughout. In the context of QCS this cannot be performed, and instead the modified quantum circuit as shown in Fig. 2a will be executed. The noisy Bell states arriving will have a phase offset T which takes into account of any time delay between Alice and Bob’s first operations. Alice and Bob will furthermore execute the algorithm in their local basis conventions. We now deduce the effect of this circuit. We can rewrite the circuit in a form closer to the original, by applying the basis rotation (4) around all the operators, and adding \(T^\dagger T = I\), which gives Fig. 2b. After the first five operations of Alice in Fig. 2b, and working in the common basis of Bob, Alice’s random unitaries are transformed as \(T^\dagger U^{(BA)\dagger }R_A^{(B)}\)U(BA)T. This is the same as the standard bilateral rotations except that Alice’s operations are transformed to a different basis. The state that results at this point of the circuit is the Werner state

where \(\left| {\psi _\varphi ^ - } \right\rangle\) = \(T^\dagger U^{(BA)\dagger }\left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{(B)}\). At this point the states have an extra phase offset, but immediately after the bilateral rotation, the circuit operates with U(BA)T, which exactly cancels this extra factor (note the opposite operator ordering conventions for quantum circuits and equation form). At this point we have a Werner state in Bob’s basis, with various circuit elements all in Bob’s basis. The purification thus proceeds as originally conceived, purifying towards the state \(\left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{(B)}\). Finally, there is one extra \(U_A^{(AB)}\) at the end of the circuit which completes the whole procedure. The state that the purification thus converges to is thus

The quantum circuit for entanglement purification. Due to the lack of synchronized clocks between Alice and Bob, the basis choice for the circuit elements by each party will be in their respective bases, labeled by (A, B). a The circuit as performed by Alice and Bob; b an equivalent circuit where all circuit elements have been transformed to the same basis choice. \({\cal B}\) = RA ⊗ RB are random bilateral rotations which are predecided by Alice and Bob, UAB transforms from Bob’s basis convention to Alice’s, T includes the effect of a time delay between the start of Alice and Bob’s operations

Thus starting from the state with an extra phase (7), the entanglement purification has converged to the singlet state with respect to the local basis choice with no relative phase φ = 0. The state (9) is exactly as desired, since any measurements that will be made on this state will be in the local basis choice. Alice and Bob would then measure this state in their local basis choice, which does not contain any extra phases as discussed in ref.26. The QCS protocol then proceeds as described in ref.16.

Algebraic evaluation of random bilateral purification protocol

This result can be also calculated by direct application of the bilateral rotations as shown in the Supplemental Material. Starting from the state ρ = pI/4 + (1 − p) \(\left| {\psi _\varphi ^ - } \right\rangle ^{({\mathrm{loc}})}\left\langle {\psi _\varphi ^ - } \right|^{({\mathrm{loc}})}\), we explicitly calculate that the bilateral rotations produce the state

The fidelity calculated using (10) agrees with that calculated from (7) which gives F = \(\left\langle {\psi ^ - } \right|\rho _\varphi \left| {\psi ^ - } \right\rangle\) = \({\textstyle{p \over 4}} + (1 - p){\mathrm{cos}}^2\left( {{\textstyle{\varphi \over 2}}} \right)\) since singlet states are invariant under bilateral rotations.The fidelity F contains an extra phase factor originating from the combination of the time delay and the different basis conventions. Since (eq. 10) is in the local basis as desired, the remaining part of the purification proceeds in the regular way.

Efficacy of the QCS

The above result removes an outstanding issue of the QCS protocol. What can we expect from a future implementation of QCS? To answer this we estimate the competitiveness of the QCS protocol in comparison to existing schemes. Currently the most accurate long-distance clock synchronization protocols are microwave-based GPS and Two-way Satellite Time and Frequency Transfer (TWSTFT)33,34, which achieve synchronizations at the level of 1 ns. The next generation laser based methods aim to improve this to the level of 100 ps5,6. The fundamental sources of error in the QCS protocol will be due to the imperfect entanglement that is distributed between Alice and Bob, and the quantum noise due to the standard quantum limit in the QCS protocol itself (see Supplemental Material). We estimate that the error in the QCS obeys a relation

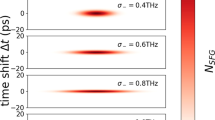

where ω is the clock frequency, N is the number of available Bell pairs for QCS, n is the number of rounds of purification performed, and Fn is the fidelity of the Bell pairs after n rounds of purification. Equation (11) is valid for 1 − Fn, \({\textstyle{{2^n} \over N}} \ll 1\). In Fig. 3a we see that there is an optimum number of purification rounds. This occurs because there is a trade-off between improving the fidelity of the Bell pairs by purification, and consuming Bell pairs for purification. Using this optimum number of purification rounds, we obtain the level of accuracy expected in the QCS algorithm in Fig. 3b. As expected one obtains an improvement in performance with both N and F0. Taking currently achievable estimates for parameters27,28 we have F0 ≈ 0.9 and N = 105, and using the Cs clock transition frequency the timescale is set by \(\omega _{{\mathrm{Cs}}}^{ - 1}\) = 17 ps, from which we obtain δt ≈ 2 ps, a considerable improvement over classical schemes. In terms of the synchronization rate, taking an Allan deviation for Cs clocks to be 10−13, if the clock is to be synchronized every second, then the synchronization error must reach or beat the uncertainty of 10−13 s. According to Fig. 3b this would require parameters in the region of F0 ≈ 0.99 and N = 108. Naturally, using larger numbers of Bell states and atoms with higher frequency clock transitions (e.g., for Sr, \(\omega _{{\mathrm{Sr}}}^{ - 1}\) = 0.4 fs) one will obtain further improvements to the synchronization error.

Discussion

In summary, we have shown that using entanglement distillation it is possible for Alice and Bob to share a singlet state in their local basis, despite not having any information about their mutual basis conventions, and including any time offset between execution of their quantum gates. The key ingredient is the incorporation of bilateral random unitaries in the entanglement purification protocol, which was not included in refs.16,26. This deterministically produces a Werner state for a singlet state in the local basis, thereby overcoming the ambiguity due to different phase definitions. This solves a major existing issue in the QCS protocol, where it was previously thought that a common phase reference (which implies synchronized clocks) are required to perform the purification. We have estimated the error of the protocol and found that it should have a performance that is considerably better than existing classical Einstein synchronization based schemes. Here we only examined the same basic protocol as given in ref.16, which has errors scaling as the standard quantum limit \(\propto 1{\mathrm{/}}\sqrt N\). Using collective states of the N Bell pairs should further improve the errors further to beat the standard quantum limit. We envision that the QCS would be particularly useful in the context of the space-based quantum network27,28,35, where satellites are each in possession of an high-precision clock. Such entanglement based schemes are a powerful way to synchronize clocks without the use of a classical channel containing the timing information, which is susceptible to the properties of the intervening medium.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file.

References

Sundararaman, B., Buy, U. & Kshemkalyani, A. D. Clock synchronization for wireless sensor networks: a survey. Ad hoc Netw. 3, 281–323 (2005).

Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Ann. der Phys. 17, 891–921 (1905).

Eddington, A. S. The Mathematical Theory of Relativity. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1924).

Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Peik, E. & Schmidt, P. O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 637 (2015).

Samain, E. et al. Time transfer by laser link-the t2l2 experiment on jason-2 and further experiments. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D. 17, 1043–1054 (2008).

Samain, E. et al. Time transfer by laser link: a complete analysis of the uncertainty budget. Metrologia 52, 423 (2015).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S., Maccone, L. & Wong, F. Clock synchronization with dispersion cancellation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 117902 (2001).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum-enhanced positioning and clock synchronization. Nature 412, 417–419 (2001).

Piester, D., Rost, M., Fujieda, M., Feldmann, T. & Bauch, A. Remote atomic clock synchronization via satellites and optical fibers. Adv. Radio Sci. 9, 1–7 (2011).

Quan, R. et al. Demonstration of quantum synchronization based on second-order quantum coherence of entangled photons. Sci. Rep. 6, 30453 (2016).

Zhou, S. et al. Applications of two-way satellite time and frequency transfer in the BeiDou navigation satellite system. Sci. China Phys., Mech. Astron. 59, 109511 (2016).

Chuang, I. L. Quantum algorithm for distributed clock synchronization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2006–2009 (2000).

Zhang, J., Long, G. L., Deng, Z., Liu, W. & Lu, Z. Quantum-enhanced positioning and clock synchronization. Phys. Rev. A. 70, 062322 (2004).

de Burgh, M. & Bartlett, S. D. Quantum methods for clock synchronization: Beating the standard quantum limit without entanglement. Phys. Rev. A. 72, 042301 (2005).

Tavakoli, A., Cabella, A., Zukowski, M. & Bourennane, M. Quantum clock synchronization with a single qubit. Sci. Rep. 5, 0782 (2015).

Jozsa, R., Abrams, D. S., Dowling, J. P. & Williams, C. P. Quantum clock synchronisation based on shared prior entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2010–2013 (2000).

Yurtserver, U. & Dowling, J. P. Lorentz-invariant look at quantum clock-synchronisation protocols based on distributed entanglement. Phys. Rev. A. 65, 052317 (2002).

Burt, A., Ekstrom, C. R. & Swanson, T. B. Comments on “Quantum Clock Synchronization Based on Shared Prior Entanglement”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 129801 (2001).

Jozsa, R., Abrams, D. S., Dowling, J. P. & Williams, C. P. Jozsa et al. Reply. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 129802 (2001).

Krčo, M. & Paul, P. Quantum clock synchronization: Multiparty protocol. Phys. Rev. A. 66, 024305 (2002).

Ben-Av, R. & Exman, I. Optimized multiparty quantum clock synchronization. Phys. Rev. A. 84, 014301 (2011).

Ren, C. & Hofmann, H. F. Clock synchronization using maximal multipartite entanglement. Phys. Rev. A. 86, 014301 (2012).

Komar, P. et al. A quantum network of clocks. Nat. Phys. 10, 582–587 (2014).

Valencia, A., Scarcelli, G. & Shih, Y. Distant clock synchronisation using entangled photon pairs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 2655–2657 (2004).

Kong, X. et al. Implementation of multiparty quantum clock synchronization. arXiv quant-ph, 1708.06050 (2017).

Preskill, J. Quantum clock synchronisation and quantum error correction. arXiv quant-ph, 0010098v1 (2000).

Yin, J. et al. Satellite-based entanglement distribution over 1200 kilometers. Science 356, 1140–1144 (2017).

Ren, J.-G. et al. Ground-to-satellite quantum teleportation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.00934 (2017).

Radnaev, A. G. et al. A quantum memory with telecom-wavelength conversion. Nat. Phys. 6, 894–899 (2010).

Reim, K. F. et al. Towards high-speed optical quantum memories. Nat. Photonics 4, 218–221 (2010).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Purification of noisy entanglement and faithful teleportation via noisy channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 722–725 (1996).

Bennett, C. H., DiVincenzo, D. P., Smolin, J. A. & Wootters, W. K. Mixed-sate entanglement and quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. A. 54, 3824–3851 (1996).

Allan, D. W. & Weiss, M. A. Accurate time and frequency transfer during common-view of a gps satellite. In 34th Annual Symposium on Frequency Control. 334–346 (IEEE, Fort Monmouth, New Jersey 1980).

Kirchner, D. Two way satellite time and frequency transfer (twstft): principle, implementation, and current performance. Review of Radio Science 1996-1999, 27–44 (1999).

Byrnes, T., Ilyas, B., Tessler, L., Jambulingam, S. & Dowling, J. P. Lorentz invariant entanglement distribution for the space-based quantum network. arXiv quant-ph, 1704.04774 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank John Preskill for discussions. T. B. is supported by the Shanghai Research Challenge Fund; New York University Global Seed Grants for Collaborative Research; National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61571301); the Thousand Talents Program for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. D1210036A); and the NSFC Research Fund for International Young Scientists (Grant No. 11650110425); NYU-ECNU Institute of Physics at NYU Shanghai; and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 17ZR1443600). J. P. D. would like to acknowledge support from the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Army Research Office, the Defense Advanced Funding Agency, the National Science Foundation, and the Northrop-Grumman Corporation. E. O. I-O. acknowledges the Talented Young Scientists Program (NGA-16-001) supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.O.I-O. and L.T. performed the calculations. J.D. and T.B. conceived and guided the work. E.O.I-O. and T.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ilo-Okeke, E.O., Tessler, L., Dowling, J.P. et al. Remote quantum clock synchronization without synchronized clocks. npj Quantum Inf 4, 40 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0090-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-018-0090-2

This article is cited by

-

Finite key effects in satellite quantum key distribution

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Spooky action at a global distance: analysis of space-based entanglement distribution for the quantum internet

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Quantum technologies in space

Experimental Astronomy (2021)

-

Towards satellite-based quantum-secure time transfer

Nature Physics (2020)

-

Quantum frequency synchronization of distant clock oscillators

Quantum Information Processing (2020)