Abstract

With the introduction of superconducting circuits into the field of quantum optics, many experimental demonstrations of the quantum physics of an artificial atom coupled to a single-mode light field have been realized. Engineering such quantum systems offers the opportunity to explore extreme regimes of light-matter interaction that are inaccessible with natural systems. For instance the coupling strength g can be increased until it is comparable with the atomic or mode frequency ω a,m and the atom can be coupled to multiple modes which has always challenged our understanding of light-matter interaction. Here, we experimentally realize a transmon qubit in the ultra-strong coupling regime, reaching coupling ratios of g/ω m = 0.19 and we measure multi-mode interactions through a hybridization of the qubit up to the fifth mode of the resonator. This is enabled by a qubit with 88% of its capacitance formed by a vacuum-gap capacitance with the center conductor of a coplanar waveguide resonator. In addition to potential applications in quantum information technologies due to its small size, this architecture offers the potential to further explore the regime of multi-mode ultra-strong coupling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconducting circuits such as microwave cavities and Josephson junction based artificial atoms1 have opened up a wealth of new experimental possibilities by enabling much stronger light-matter coupling than in analog experiments with natural atoms2 and by taking advantage of the versatility of engineered circuits. With strong coupling,3 where the coupling is larger than the dissipation rates γ and κ of the atom and mode respectively, experiments such as photon-number resolution4 or Schrödinger-cat revivals5 have beautifully displayed the quantum physics of a single-atom coupled to the electromagnetic field of a single mode. As the field matures, circuits of larger complexity are explored,6,7,8 opening the prospect of controllably studying systems that are theoretically and numerically difficult to understand.

One example is the interaction between an (artificial) atom and an electromagnetic mode where the coupling rate becomes a considerable fraction of the atomic or mode eigen-frequency. This ultra-strong coupling (USC) regime, described by the quantum Rabi model, shows the breakdown of excitation number as conserved quantity, resulting in a significant theoretical challenge.9,10 In the regime of \(g{\mathrm{/}}\omega _{a,m} \simeq 1\), known as deep-strong coupling (DSC), a symmetry breaking of the vacuum is predicted11 (i.e., qualitative change of the ground state), similar to the Higgs mechanism or Jahn–Teller instability. To date, U/DSC with superconducting circuits has only been realized with flux qubits6,12 or in the context of quantum simulations.13,14 Using transmon qubits for USC is interesting due to their higher coherence rates15 as well as their weakly-anharmonic nature, allowing the exploration of a different Hamiltonian than with flux qubits.16 Since transmon qubits are currently a standard in quantum computing efforts,17,18,19 implementing USC in a transmon architecture could also have technological applications by decreasing gate times20 as well as the performance of quantum memories.21 With very strong coupling rates, the additional modes of an electromagnetic resonator become increasingly relevant, and U/DSC can only be understood in these systems if the multi-mode effects are correctly modeled. Previous extensions of the Rabi model have lead to un-physical predictions of dissipation rates22 or the Lamb shift23 arising from a multi-mode interaction. Recently, new models have been developed in which these unphysical predictions no longer arise.23,24 However, experiments have yet to reach a parameter regime where such physics becomes relevant.

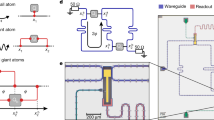

Here, we realize a superconducting quantum circuit with a transmon qubit25 in the multi-mode USC regime where past extensions of the standard quantum Rabi models have failed. The qubit consists of a superconducting island shorted to ground by two Josephson junctions in parallel (or SQUID), which is suspended above the voltage anti-node of a quarter-wavelength (λ/4) coplanar-waveguide microwave cavity as shown in Fig. 1a, b. This vacuum-gap transmon architecture offers various possibilities that could prove technologically useful; it’s an order of magnitude smaller (30 μm in diameter) than normal transmon qubits and it offers the possibility to couple in-situ to the mechanical motion of the suspended island by applying a voltage bias to the center conductor.26 In this study we use this architecture to maximize the coupling. Indeed, the coupling rate is proportional to the capacitance ratio β between the qubit capacitance to the resonator C c and the total qubit capacitance C Σ, β = C c /C Σ. In this architecture, the vacuum-gap capacitance C c dominates, leading to β = 0.88. Note that by changing the position of the transmon along the resonator or its capacitance ratios, its coupling can be reduced to standard coupling rates for other applications.

Vacuum-gap transmon circuit architecture. a Schematic diagram of the equivalent circuit containing a λ/4 microwave cavity, which on the left is coupled through a shunt capacitor38 to a 50 Ω port for reflection measurements. On the right, at the voltage anti-node of the resonator, it is capacitively coupled to a transmon qubit. b Detailed schematic of the transmon qubit showing the vacuum-gap capacitor between the center conductor of the resonator and a suspended superconducting island, which is connected to ground with two Josephson junctions in SQUID geometry (note the matched colors with (a)). c Optical image of a typical device implementing the circuit. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. d Zoom-in on the qubit showing the suspended capacitor plate above the end of the resonator connected to ground by the junctions. Scale bar corresponds to 30 μm

Results

Multi-mode effects play a key role in the physics of this system, but we will start by considering the more simple case of the fundamental mode of the resonator interacting with the transmon (with levels \(\left| g \right\rangle\), \(\left| e \right\rangle\), \(\left| f \right\rangle\), ... of increasing energy). This is described using an extension of the quantum Rabi Hamiltonian25

Here \(\hat a\) \(({\hat b})\) is the annihilation operator for the resonator (transmon) excitations, with frequency ω 1 (ω a (Φ)) and ħ is the reduced Planck constant. The third term introduces the weak anharmonicity of the transmon, quantified by the charging energy \(E_c \simeq e^2{\mathrm{/}}2C_\Sigma\) and the last term describes the coupling of the transmon to the resonator. Changing the magnetic flux Φ through the SQUID loop of the transmon allows us to vary the Josephson energy E J (Φ) and hence the frequency \(\hbar \omega _a(\Phi ) \simeq \sqrt {8E_J(\Phi )E_c} - E_c\) and the coupling g(Φ)25

where V zpf is the voltage zero point fluctuations of the microwave cavity and e is the electron charge. Equations (1) and (2) are only valid in the limit \(E_J(\Phi ) \gg E_c\), for the two devices (A and B) presented here, E J (0)/E c = 79 (A) and 53 (B). In device A, USC is due to β = 0.88, whereas β ~ 0.1 in usual planar geometries. For a transmon qubit coupled to a single mode, a natural limit on the coupling rate is given by27

We refer to Hamiltonian (1) as an extended Rabi model due to the multiple excitation levels of the transmon. Despite this deviation from the Rabi model, quantitatively shown in Supplementary Fig. S5, the system is still expected to bear features of the USC Rabi model such as a non-trivial ground state as demonstrated in ref. 16.

The light-matter interaction has two types of contributions. The first terms conserve excitations, and remain after applying the rotating-wave approximation (RWA). The second terms, called counter-rotating terms, add and extract excitations from the qubit and resonator in a pair-wise fashion. For sufficiently small couplings \(g{\mathrm{/}}\omega _{a,m} \ll 0.1\) the non-RWA terms can be neglected reducing the Rabi model to the Jaynes-Cummings model.28 For higher couplings g/ω a,m ≳ 0.1 the RWA is no longer applicable and the excitation number conservation of the JC model is replaced by a conservation of excitation number parity.10,29 In this regime, making the RWA would lead to a deviation in the energy spectrum of the system known as Bloch–Siegert shift χ BS, marking the entry into the USC regime.30

Our samples, depicted in Fig. 1c, d, are fabricated on a sapphire substrate and an alloy of molybdenum-rhenium (MoRe) is used as superconductor.31 In a five step electron beam lithography process we pattern the microwave resonator, shunt capacitor dielectric, vacuum-gap sacrificial layer and lift-off mask for the MoRe suspension (see methods for more details). In the last step we pattern and deposit the Josephson junctions using aluminum shadow evaporation and perform the release of the vacuum-gap capacitor and aluminum lift-off in the same step. In this study we spectroscopically characterize two devices A and B, with vacuum-gap sizes of 155 nm and 350 nm, for A and B respectively.

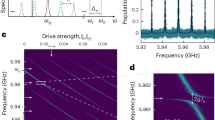

Figure 2 shows the spectral response of device A using single-tone microwave reflectometry at ~14 mK. By measuring the complex scattering parameter S 11(ω) of the circuit as a function of an external magnetic field, we can probe the absorption of the circuit at a given frequency within the circulator and amplifier bandwidth of 4–8 GHz. The transitions of the circuit appear as a dip in the magnitude of the scattering parameter, \(\left| {S_{11}} \right|\), thereby mapping the spectrum of the circuit. At high measurement drive powers, we measure the bare fundamental mode of the resonator to have a frequency of 4.60 GHz, with internal and external quality factors of Q int = 3800 and Q ext = 2600 respectively. From the avoided crossing, depicted in Fig. 2a, b, we determine the vacuum Rabi splitting (VRS) to be ΔVRS = 2π × 1.19 GHz. This provides an estimate of the coupling through the relation \(\Delta _{{\mathrm{VRS}}} \simeq 2g\). The coupling exceeds the linewidth of the resonator and qubit, measured to be κ = 2π × 3 MHz and γ ~ 2π × 20 MHz respectively, such that our system satisfies the condition for strong-coupling \(g \gg \kappa ,\gamma\). We obtain a ratio \(g{\mathrm{/}}\omega _1 \simeq \Delta _{{\mathrm{VRS}}}{\mathrm{/}}2\omega _1 = 0.13\) indicating we are in the USC regime.

Vacuum Rabi splitting. a The spectral response of device A (155 nm vacuum-gap capacitor) is shown as a function of flux in a single-tone reflection measurement plotted as \(\left| {S_{11}} \right|\) (see Methods and Supplementary Sec. S1). The blue dashed lines indicate the bare (uncoupled) frequency of the fundamental cavity mode, ω 1, and the transition frequencies of the transmon from the ground state \(\left| g \right\rangle\), to its first and second excited states, \(\left| e \right\rangle\) and \(\left| f \right\rangle\) respectively. The red lines show the hybridized state transitions of the coupled system as fitted from the full spectrum (shown in Supplementary Fig. S2). The green lines indicate the dressed state transitions using the rotating wave approximation (RWA) for the same circuit parameters. Note that the splitting is not symmetric with respect to the point at which qubit and mode frequency cross. This is notably due to the renormalization of the charging energy that comes from considering higher resonator modes.23 b Line-cut showing the vacuum Rabi splitting of the qubit transition with ω 1, resulting in a separation of ΔVRS = 2π × 1.19 GHz, which is about 281 linewidths of separation. c Close up of the spectrum around half a flux quantum (anti-sweet spot), where the qubit frequency is minimal (\(\omega _a \mathbin{\lower.3ex\hbox{$\buildrel<\over\\ {\smash{\scriptstyle \sim}\vphantom{_x}}$}} 2\pi \times 1.1\) GHz from the fitted model). There we observe a discrete transition of the spectral response of the circuit towards the bare cavity, ω 1, which we attribute to a decoupling of the qubit and resonator due to a thermally populated qubit. Additionally we observe a small avoided crossing with the g ↔ f transition

Figure 2c shows a detailed zoom of the observed spectrum close to half a flux quantum \(\left( {\Phi {\mathrm{/}}\Phi _0 \simeq 0.5} \right)\). In this regime, E J becomes small, such that the qubit frequency goes towards zero for very symmetric junctions, and negligible loop inductance, and the transmon becomes more like a Cooper-pair box (CPB) as the ratio of E J /E c drops.25 Note that in this regime the physics of the qubit can no longer be described by the Duffing oscillator of Eq. (1), but rather by the CPB Hamiltonian as was used in all fits of the data.23 In this flux region, we observe two notable features. The first is an anti-crossing at Φ/Φ0 ~ 0.471, which we attribute to an avoided crossing with the \(\left| g \right\rangle\) to \(\left| f \right\rangle\) transition of the qubit (indicated with the blue dashed line on the right). This shows that in this flux region the qubit behaves like a CPB as such transitions are exponentially suppressed in the transmon regime.25 The second feature is a jump of the dressed cavity to the frequency of the bare cavity at Φ/Φ0 ~ 0.485. Such jumps to the bare cavity frequency have been observed before as quantum to classical transitions by applying either high powers of a coherent drive or white noise to the cavity.32,33 In our experiment the critical power of the drive tone that determines the onset of this quasi-harmonic regime is strongly dependent on the flux-bias point. For driving powers corresponding to less than N d ~ 40 intra-cavity photons, the bar-like feature becomes power independent, measured with drive powers as low as N d ≲ 0.04, ruling out a role of the applied drive tone in this feature. We attribute this quenching of the light-matter interaction to a thermal excitation of the low frequency qubit by the environment. We believe that the transition is observable in our experiment due to a combination of very symmetric junctions in device A, resulting in qubit frequencies that can be excited by the thermal bath of the dilution refrigerator, together with the USC regime that still significantly dresses the cavity resonance even for such large detunings.

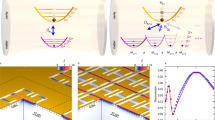

Figure 3 depicts the spectrum of device B over the full flux periodicity (for device A see Supplementary Fig. S2). It is a composition of a single tone measurement, as in Fig. 2, combined with a two-tone spectroscopy measurement.3 In such a measurement the change in cavity response \(\tilde S_{11}(\omega )\) is probed using a weak probe tone as a function of a second drive tone at the qubit. Due to the qubit-state dependent dispersive shift of the cavity at ω 1, the reflection of the weak probe tone changes as the drive tone excites the qubit. The measured qubit linewidth is γ ~ 2π × 20 MHz. From the loss tangent of previous aluminum vacuum-gap capacitor measurements,34 we would expect a 100 kHz linewidth. Our experiment differs by the use of MoRe with PMGI as a sacrificial layer; differences in the superconductor to vacuum interface could thus explain the large losses. Although this experiment shows high qubit dissipation rates, the fact that the vacuum-gap Transmon has 90% of the electric fields in vacuum could make it a practical architecture to optimize qubit decoherence, since only the superconductor to vacuum interface is relevant to engineer.

Multi-mode spectrum. Color plot composed of two spectroscopic measurements of device B (350 nm vacuum-gap capacitor). The bottom frame, \(\left( {\cal I} \right)\), shows data obtained as in Fig. 2. The top frame, \(\left( {{\cal I}{\cal I}} \right)\), shows data from a two-tone spectroscopy measurement from the change in the reflection phase of a weak probe tone at the cavity frequency (ω 1), as a function of a secondary drive tone. We plot the derivative of this phase \(\delta \theta _{11} = \partial \varphi \left[ {\tilde S_{11}(\omega )} \right]{\mathrm{/}}\partial \omega\). Frame \(\left( {{\cal I}{\cal I}^*} \right)\) is a mirrored copy of the same data. The blue dashed lines show the transition frequencies of the uncoupled cavities (ω 1, ω 2) and the first transition (\(\left| g \right\rangle\) to \(\left| e \right\rangle\)) of the qubit. The red and green dashed lines show the hybridized spectrum without and with a RWA, respectively. Note that we observe in the top frame a few avoided crossings indicating the presence of two-level systems (TLSs) strongly coupled to the qubit. The inset shows the vacuum Rabi splitting of the qubit with ω 2, giving Δ2,VRS = 2π × 1.82 GHz, plotted as change in reflection angle of the probe tone at ω 1

We observe an avoided crossing of the qubit with the fundamental mode ω 1 (Δ1,VRS = 2π × 0.63 GHz) and the second mode ω 2, and the frequency maximum of the qubit of ω a = 2π × 14.2 GHz. From the avoided crossing of the qubit with the second mode we obtain a splitting of Δ2,VRS = 2π × 1.82 GHz, as shown in the inset. We observe that these two splittings follow the relation \(\Delta _{2,{\mathrm{VRS}}} \simeq 3\Delta _{1,{\mathrm{VRS}}}\), thereby we observe that the scaling of the VRS evolves linearly with mode number.35 Due to a resolved Bloch–Siegert shift (explained below), we conclude that this device is in the USC regime, wherein the higher modes of the resonator cannot be neglected.

From the observations of USC to multiple modes in our experiment, it is clear that a quantitative analysis of our experiment should be based on a model that includes multiple modes of the cavity. Typically this has been done by extending the Rabi model (Eq. (1)) through a square-root increase in coupling strength with mode number \(g_m = \sqrt {2m - 1} g_0\). However, as is well established in the literature, such straightforward extensions of the JC and Rabi model to multi-mode systems suffer from divergence problems.22,35 In particular, there is a problem with the predicted qubit frequency due to a divergence of the Lamb shift when the dispersive shift from all of the modes is included.23 In previous experiments where the coupling is small, and the size of the qubit compared to the cavity wave-length is large, a natural cut-off in the number of modes seems to solve these issues and does not reveal the full extent of divergence problems in extended Rabi models.35 In our case, the small size of our qubit and the USC regime yield an unphysical 25 GHz Lamb shift of the qubit following this methodology. Another cut-off associated with the non-zero capacitance of the qubit to ground23 leads to a similar shift. This issue can be overcome by using black-box circuit quantization,36 but with this method we would lose the strict separation of atomic and photonic degrees of freedom typical of the Rabi model, which is essential to estimating the role of counter-rotating terms in the system’s spectrum. Additionally, the analysis is then limited to the weakly anharmonic regime of the transmon qubit whilst our system also enters the Cooper-pair box regime (see Fig. 2c).

Overcoming this issue led to recent theoretical work,23 where a first-principle quantum circuit model was developed based on a lumped element equivalent of this transmon architecture. This model circumvents the divergence problems of conventional extensions of the Hamiltonian. The red dashed lines in Figs. 2 and 3 show a fit of our observed spectrum to the model, demonstrating excellent agreement as discussed in Supplementary Sec. S4. The fits from the circuit model also allow the extraction of the bare cavity and qubit lines, shown by the blue dashed lines. Note that in the model used, the bare qubit frequency is dependent on the number of modes considered. This renormalization compensates the Lamb shift of higher modes. As discussed in ref. 23, this can be understood by modeling the modes of the resonator as a series of LC oscillators. This so-called Foster decomposition is exact for an infinite number of modes. In the model, we define the bare qubit as current oscillations flowing only through the Josephson junction. The impedance path through only the series capacitors of the resonator equivalent circuit diverges with the number of included modes. Charge from currents through the junction can therefore no longer oscillate on the coupling capacitor when an infinite number of modes are included. The effective capacitance of the bare qubit is thus a function of the number of modes considered and so is the relevant bare qubit frequency. This consideration notably leads to the vacuum Rabi splittings not being symmetrical with respect to the point at which bare qubit and mode cross in Figs. 2 and 3. An additional feature of the quantum circuit model is that we are able to quantify the relevance of the counter-rotating terms of the interaction between the qubit and the resonator modes. To do this, we performed the same calculation but removed the counter-rotating terms from the Hamiltonian of the model. The result is shown by the dashed green lines and allows us to unambiguously extract the resulting vacuum Bloch–Siegert shift χ BS, characteristic of the USC regime.30 For device A for example, we find a shift of χ BS = 2π × 62 MHz (see Fig. 2), which is about 20 times the cavity linewidth, clearly demonstrating our experiment is in the USC regime. Finally we can extract the magnitude of the coupling at its maximum (Φ = 0) and obtain for device A a value of 897 MHz, resulting in a coupling ratio of g/ω 1 = 0.195

By examining the composition of the eigenstates obtained from our model, we expect that the qubit should be strongly hybridized with multiple modes of the cavity. In Fig. 4, we show measurements demonstrating this hybridization. Using two tone spectroscopy as in Fig. 3, we are able to observe the higher-modes, by monitoring the response of the hybridized fundamental mode while driving the higher modes. Figure 4a shows a measurement of the third mode of the cavity ω 3 as a function of flux. Due to the strong hybridization, we observe a flux tuning of ~70 MHz despite a detuning from the qubit by ~7 GHz. The red dashed line shows the expected dressed state of ω 3 as predicted from our model, which is in agreement with the data. The bare frequency of this mode is 20.98 GHz indicated with the blue dashed line, from which we extract a dispersive shift of 200–270 MHz. Furthermore from the model we find that the counter-rotating terms are crucial for this physics, as the predicted spectrum shifts more than 50 MHz by removing them from the Hamiltonian, as indicated with the green dashed line. Figure 4b shows such a measurement up to 45 GHz. In addition to the third mode shown in Fig. 4a, we also observe the fourth and the fifth mode of the cavity, demonstrating the qubit induced hybridization over five modes of the cavity extended up to 38 GHz.

Qubit mediated mode–mode interactions. a Two-tone spectroscopy measurement showing the flux dependence of the third mode ω 3 as obtained and shown in Fig. 3. Due to the strong hybridization over multiple modes, we observe that the qubit-mediated mode–mode coupling is sufficient to observe the effect of driving ω 3 by monitoring the response of the fundamental mode ω 1. The red dashed line indicates the dressed state of ω 3 and the blue dashed line indicates the bare cavity. The green dashed line indicates the predicted line using the RWA, showing the effect of removing the counter-rotating terms, from which we obtain a Bloch–Siegert shift of 45 MHz. b Using the same measurement technique, we show a trace of the normalized reflection coefficient of a weak probe tone positioned at the slope of the resonance of the fundamental mode as a function of a higher frequency drive tone. Here we observe clearly the harmonics of the cavity, including the fourth-mode (ω 4) and fifth-mode (ω 5). The response for the same drive tone power clearly decreases for higher modes as these are further detuned. The data traces measuring ω 5 is 39.5 dB higher in drive power than the other traces, but making power comparisons is impractical as our microwave measurement setup uses components specified up to 18 GHz. The leftmost peak corresponds to the onset of a frequency region where the system is driven to its linear regime32 due to the strong drive powers necessary to acquire this data. c Three panels showing a close up of the resonances of ω 3, ω 4, and ω 5, following the harmonics of the fundamental frequency of ω 1 = 2π × 4.268 GHz

Discussion

To conclude, we have introduced a novel circuit architecture based on the transmon qubit,25 where a vacuum-gap capacitor significantly dominates the total capacitance of the qubit. Being ten times smaller than the existing transmon architectures, together with the prospect of higher possible coherence by localizing electric fields in vacuum, this new device could have potential applications in quantum computing technologies. Here, we have used this new architecture to maximize the coupling between the qubit and the microwave resonator by increasing the capacitance participation ratio to β ~ 0.88. Doing so, we realized couplings with the fundamental mode up to 850 MHz, well within the USC limit, and found that the multi-mode character of the λ/4 resonator plays a crucial role in the physics of the circuit. Using a quantum circuit model, we found a Bloch–Siegert shift induced by counter-rotating terms of up to χ BS = 2π × 62 MHz. Combining this architecture with high-impedance microwave resonators27,37 and a smaller free spectral range,7 we expect to reach even further into the multi-mode ultra-strong coupling regime to probe exotic states of light and matter.16

Methods

Fabrication

In the first step, we define the bottom metalization layer of the cavity, including the bottom layers of the shunt-capacitor and the vacuum-gap capacitor, on top of a sapphire substrate. We use magnetron sputtering to deposit a 45 nm thick layer of 60–40 molybdenum-rhenium (MoRe) alloy and pattern it by means of electron-beam lithography (EBL) and SF6/He reactive-ion etching (RIE). For the definition of the shunt-capacitor dielectric, we deposit a 100 nm thick layer of silicon nitride by means of plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition and perform the patterning by EBL and wet etching in buffered hydrofluoric acid. In a third EBL step we pattern the sacrificial layer for the vacuum-gap capacitor, which in our samples consists of a ~160 nm thick layer of the electron-beam resist PMGI SF7 diluted 2:1 with cyclopentanone. After the development of the sacrificial layer in L-ethyl-lactate, stopped by rinsing with isopropanol, we reflow the patterned PMGI for 180 s at 250 °C in order to slightly smoothen the stepped edge, facilitating the sidewall metalization in the next step. The shunt-capacitor and vacuum-gap capacitor top electrodes are fabricated subsequently by means of lift-off technique. First, we perform EBL to pattern the corresponding PMMA resist layer and secondly, we sputter deposit a 120 nm thick layer of MoRe on top. We do the lift-off in hot xylene, while the sacrificial layer of the vacuum-gap capacitor is not attacked in this process and thus remains unchanged. In the last step, we fabricate the Josephson junctions using a PMGI/PMMA bilayer lift-off mask, EBL and aluminum shadow-evaporation. We perform a simultaneous Al lift-off and drum release in the resist stripper PRS3000. Finally, we dry the sample in an IPA filled beaker on a hot plate.

Model and fit

The model used is described in ref. 23. It includes multiple modes and five transmon excitation levels. This model was fitted to the data using a least-square minimization routine with four free parameters, the coupling capacitance, the Josephson energy, gate charge and capacitance to ground, the other parameters being available through direct measurement. Further details on both the model and fitting process is given in Supplementary Sec. S3, S4.

Data visualization

For the color plots of Figs. 2–4, we applied an image processing filter using Spyview,39 which histogrammically subtracts the mean of each line of constant frequency with outlier rejection, 90% low, 2% high to remove flux-independent features such as cable resonances.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the finding of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: an outlook. Science. 339, 1169–1174 (2013).

Raimond, J.-M., Brune, M. & Haroche, S. Manipulating quantum entanglement with atoms and photons in a cavity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 565 (2001).

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature. 431, 162–167 (2004).

Schuster, D. I. et al. Resolving photon number states in a superconducting circuit. Nature. 445, 515–518 (2007).

Kirchmair, G. et al. Observation of quantum state collapse and revival due to the single-photon kerr effect. Nature. 495, 205–209 (2013).

Forn-Daz, P. et al. Ultrastrong coupling of a single artificial atom to an electromagnetic continuum in the nonperturbative regime. Nat. Phys. 13, 39–43 (2016).

Sundaresan, N. M. et al. Beyond strong coupling in a multimode cavity. Phys. Rev. X. 5, 021035 (2015).

McKay, D. C., Naik, R., Reinhold, P., Bishop, L. S. & Schuster, D. I. High-contrast qubit interactions using multimode cavity qed. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 080501 (2015).

Casanova, J., Romero, G., Lizuain, I., Garca-Ripoll, J. J. & Solano, E. Deep strong coupling regime of the jaynes-cummings model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 263603 (2010).

Braak, D. Integrability of the rabi model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100401 (2011).

Garziano, L., Stassi, R., Ridolfo, A., Di Stefano, O. & Savasta, S. Vacuum-induced symmetry breaking in a superconducting quantum circuit. Phys. Rev. A. 90, 043817 (2014).

Yoshihara, F. et al. Superconducting qubit-oscillator circuit beyond the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 13, 44–47 (2017).

Langford, N. K. et al. Experimentally simulating the dynamics of quantum light and matter at ultrastrong coupling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1610.10065.pdf (2016).

Braumüller, J. et al. Analog quantum simulation of the Rabi model in the ultra-strong coupling regime. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1611.08404.pdf (2016).

Gu, X., Kockum, A. F., Miranowicz, A., Liu, Y.-x. & Nori, F. Microwave photonics with superconducting quantum circuits. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1707.02046.pdf (2017).

Andersen, C. K. & Blais, A. Ultrastrong coupling dynamics with a transmon qubit. N. J. Phys. 19, 023022 (2017).

Takita, M. et al. Demonstration of weight-four parity measurements in the surface code architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 210505. https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.210505 (2016).

Kelly, J. et al. State preservation by repetitive error detection in a superconducting quantum circuit. Nature. 519, 66–69 (2015).

Ristè, D. et al. Detecting bit-flip errors in a logical qubit using stabilizer measurements. Nat. Commun. 6, 6983 (2015).

Romero, G., Ballester, D., Wang, Y. M., Scarani, V. & Solano, E. Ultrafast quantum gates in circuit QED. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 120501 (2012).

Stassi, R. & Nori, F. Quantum memory in the ultrastrong-coupling regime via parity symmetry breaking. arXiv:1703.08951 (2017).

Houck, A. A. et al. Controlling the spontaneous emission of a superconducting transmon qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 080502 (2008).

Gely, M. F. et al. Convergence of the multimode quantum rabi model of circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. B 95, 245115 (2017).

Malekakhlagh, M., Petrescu, A. & Türeci, H. E. Cutoff-free circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 073601 (2017).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A. 76, 042319 (2007).

Pirkkalainen, J.-M. et al. Hybrid circuit cavity quantum electrodynamics with a micromechanical resonator. Nature. 494, 211–215 (2013).

Bosman, S. J. et al. Approaching ultrastrong coupling in transmon circuit QED using a high-impedance resonator. Phys. Rev. B 95, 224515 (2017).

Jaynes, E. T. & Cummings, F. W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE. 51, 89–109 (1963).

Niemczyk, T. et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics in the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 6, 772–776 (2010).

Forn-Daz, P. et al. Observation of the bloch-siegert shift in a qubit-oscillator system in the ultrastrong coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 237001 (2010).

Singh, V., Schneider, B. H., Bosman, S. J., Merkx, E. P. J. & Steele, G. A. Molybdenum-rhenium alloy based high-q superconducting microwave resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 222601 (2014).

Bishop, L. S., Ginossar, E. & Girvin, S. M. Response of the strongly driven jaynes-cummings oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 100505 (2010).

Fink, J. M. et al. Quantum-to-classical transition in cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 163601 (2010).

Cicak, K. et al. Low-loss superconducting resonant circuits using vacuum-gap-based microwave components. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 093502 (2010).

Filipp, S. et al. Multimode mediated qubit-qubit coupling and dark-state symmetries in circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. A. 83, 063827 (2011).

Nigg, S. E. et al. Black-box superconducting circuit quantization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 240502 (2012).

Samkharadze, N. et al. High-kinetic-inductance superconducting nanowire resonators for circuit qed in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Appl. 5, 044004 (2016).

Bosman, S. J., Singh, V., Bruno, A. & Steele, G. A. Broadband architecture for galvanically accessible superconducting microwave resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 192602 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Enrique Solano, Adrian Parra-Rodriguez, and Enrique Rico Ortega for valuable input and discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.B. and G.A.S. conceived the experiment. S.J.B. designed and fabricated the devices. V.S., A.B., and G.A.S. provided input for the fabrication. S.J.B. and M.F.G. did the measurements with the input of D.B. and G.A.S. M.F.G. and D.B. performed the data analysis with the input of S.J.B. and G.A.S. Manuscript was written by S.J.B., M.F.G., and G.A.S., and all authors provided comments to the manuscript. G.A.S. supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bosman, S.J., Gely, M.F., Singh, V. et al. Multi-mode ultra-strong coupling in circuit quantum electrodynamics. npj Quantum Inf 3, 46 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0046-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0046-y

This article is cited by

-

Sudden change of the photon output field marks phase transitions in the quantum Rabi model

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Extremely large Lamb shift in a deep-strongly coupled circuit QED system with a multimode resonator

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Noisy intermediate-scale quantum computers

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Multi-party Entanglement Generation Through Superconducting Circuits

International Journal of Theoretical Physics (2023)

-

Cavity electromechanics with parametric mechanical driving

Nature Communications (2020)