Abstract

The strong coupling regime is essential for efficient transfer of excitations between states in different quantum systems on timescales shorter than their lifetimes. The coupling of single spins to microwave photons is very weak but can be enhanced by increasing the local density of states by reducing the magnetic mode volume of the cavity. In practice, it is difficult to achieve both small cavity mode volume and low cavity decay rate, so superconducting metals are often employed at cryogenic temperatures. For an ensembles of N spins, the spin–photon coupling can be enhanced by \(\sqrt N\) through collective spin excitations known as Dicke states. For sufficiently large N the collective spin–photon coupling can exceed both the spin decoherence and cavity decay rates, making the strong-coupling regime accessible. Here we demonstrate strong coupling and cavity quantum electrodynamics in a solid-state system at room-temperature. We generate an inverted spin-ensemble with N ~ 1015 by photo-exciting pentacene molecules into spin-triplet states with spin dephasing time \(T_2^*\sim 3\) μs. When coupled to a 1.45 GHz TE01δ mode supported by a high Purcell factor strontium titanate dielectric cavity (\(V_{\mathrm{m}}\sim 0.25\) cm3, Q ~ 8,500), we observe Rabi oscillations in the microwave emission from collective Dicke states and a 1.8 MHz normal-mode splitting of the resultant collective spin–photon polariton. We also observe a cavity protection effect at the onset of the strong-coupling regime which decreases the polariton decay rate as the collective coupling increases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Collective light-matter interactions are fundamental to cavity quantum electrodynamics (cQED)1 and a key feature is the strong coupling regime, where excitations are coherently transferred between different quantum systems over timescales significantly shorter than their lifetimes. A striking example is the Dicke state,2 responsible for the enigmatic phenomenon of super-radiance, where the rate of emission from an ensemble of emitters is proportional to the square of their number. The enhanced coupling of Dicke states to electromagnetic radiation has been utilised experimentally for studying atomic gases in high-finesse optical cavities,3 emitters near plasmonic nanoparticles,4 electron spins coupled to superconducting qubits5,6 and sub-Hertz linewidth super-radiant lasers.7,8,9 Typically, cryogenic cooling is required to polarise the spin population and mitigate spin dephasing and cavity mode decay. Here we report strong-coupling and long-lived collective Rabi oscillations at room-temperature between Dicke states, in an optically excited spin-triplet ensemble, and a cavity mode supported by a strontium titanate (STO) dielectric resonator at 1.45 GHz. The spin ensemble becomes highly correlated through stimulated emission with suppressed spin decoherence due to a cavity protection effect.10,11,12

Consider a collection of N two-level systems, which can be regarded as pseudo spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) particles, resonantly coupled to a cavity mode where the distance between them is much less than the cavity mode’s wavelength. This system is described by the Tavis–Cummings Hamiltonian13 within the rotating wave approximation:

where \(g_{\mathrm{e}} = g_{\mathrm{s}}\sqrt N\) is the enhanced collective spin–photon coupling strength, g s is the single spin–photon coupling strength, ω c is the cavity frequency, ω s is the spin (two-level) transition frequency, a † (a) are the cavity photon creation (annihilation) operators, S z is the collective inversion operator and \(\tilde S^ \pm\) are the normalised collective spin operators. The collective inversion operator is defined by \(S^z = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_j^N \sigma _j^z\), where \(\sigma _j^z\) is the inversion operator for the jth spin, and the normalised spin operators are defined by \(\tilde S^ \pm = N^{ - \frac{1}{2}}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_j^N \sigma _j^ \pm\), where \(\sigma _j^ \pm\) are the pseudo-spin ladder raising/lowering operators. The eigenstates are the Dicke states: \(\left| {J,M} \right\rangle\) where J = 0, 1, …, N/2 and M = −J, …, J, which form a finite non-degenerate ladder of N + 1 levels. The Tavis–Cummings Hamiltonian therefore describes the joint evolution of cavity mode and Dicke states along separate ladders of equidistant states.

The strong coupling regime can be achieved for single quantum emitters interacting with photons within electromagnetic fields through their electric dipole moment,14 however the magnetic coupling strength of single spins to photons is typically far too weak at microwave frequencies. By placing a spin in a resonant cavity, the coupling can be enhanced through the Purcell effect15 where the local density of photonic states is modified by the geometry. The coupling strength of a single spin to a photon is then given by \(g_{\mathrm{s}} = \gamma \sqrt {\mu _0\hbar \omega _{\mathrm{c}}{\mathrm{/}}2V_{\mathrm{m}}}\), where γ is the electron gyromagnetic ratio, μ 0 is the permeability of free-space, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, ω c is the angular frequency of the cavity field and V m is the magnetic mode volume. Furthermore, the spin–photon coupling strength g e for an ensemble of N spins is enhanced by a factor \(\sqrt N\).6,16 Hence, for a sufficient number of spins N and small mode volume V m, it should be possible for the ensemble spin–photon coupling strength to exceed both the decay rate of the cavity mode κ c and the spin dephasing rate of the spins κ s, taking the system into the strong coupling regime.

Results

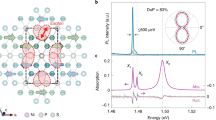

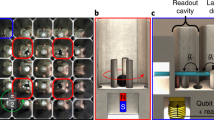

In order to satisfy this condition at room-temperature, we utilise a system comprising spin-triplets in pentacene molecules to generate a polarised (inverted) population of N spins and a cavity with small magnetic mode volume, \(V_{\mathrm{m}}\sim 10^{ - 5}\lambda ^3\), where λ is the free-space wavelength (see Fig. 1d). Following photo-excitation of pentacene in zero magnetic field, the non-degenerate X, Y, Z sub-levels of the T 1 spin-triplet are rapidly populated in the ratios 0.76 : 0.16 : 0.08, respectively17 (see Fig. 1a). Since the fluorescence lifetime of photo-excited singlet states in pentacene is ~9 ns and the intersystem crossing singlet-triplet quantum yield is 0.625,18 the singlet-triplet transition lifetime is expected to be ~14 ns. The initial inversion is S z ≈ 0.8N, where N is the number of pentacene molecules excited into either the \(\left| e \right\rangle \equiv \left| X \right\rangle\) or \(\left| g \right\rangle \equiv \left| Z \right\rangle\) states, which at zero magnetic field have a frequency splitting of ω s/2π ≈ 1.45 GHz. The \(\left| Y \right\rangle\) state does not play a significant role and shall not be considered further. The cavity is similar to the one reported for a miniaturised room-temperature maser which uses a hollow cylinder of STO, but houses a pentacene-doped p-terphenyl crys tal with a much higher concentration of 0.053% mol/mol than in previous studies.19,20 The TE01δ mode has a frequency tuned to the \(\left| e \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| g \right\rangle\) spin transition, ω c ≈ ω s ≈ 2π × 1.45 GHz. This mode has a magnetic field dipole directed along the cylindrical axis (Fig. 1b) which, via the S y spin-operator, induces transitions between the \(\left| e \right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left| g \right\rangle\) states in suitably aligned pentacene molecules. STO has a high electric permittivity (ε r ≈ 320) that allows a sub-wavelength (\(\lambda _0{\mathrm{/}}18\sim 1\) cm) cavity to be constructed with a mode volume V m of 0.25 cm3. An optical parametric oscillator (OPO) generated λ ~ 592 nm pulses of 5.5 ns duration and energy up to 15 mJ at a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The 4 mm diameter (Gaussian profile) beam of the OPO was focussed onto the 3 mm diameter pentacene-doped p-terphenyl crystal by the high refractive index (n ~ 2.6) of the STO. Numerical modelling of the penetration of optical pulses into the pentacene-doped p-terphenyl allowed the number N of excited pentacene molecules to be estimated18 and revealed that the spin-triplet yield is a linear function of the incident optical pulse energy (see Supplementary Information). For an optical pulse energy of 15 mJ, the number of pentacene molecules N excited into the \(\left| e \right\rangle\) and \(\left| g \right\rangle\) states was estimated to be ~7 × 1014, with an initial inversion S z ~ 6 × 1014.

Pentacene:p-terphenyl/STO cQED system. a Simplified Jablonski diagram showing optical pumping scheme that prepares an inverted population. The \(\left| X \right\rangle \equiv \left| e \right\rangle\) and \(\left| Z \right\rangle \equiv \left| g \right\rangle\) triplet sub-levels constitute a two-level system of pseudo spin-1/2 particles with initial relative population 9:1. The difference in energy between the \(\left| e \right\rangle\) and \(\left| g \right\rangle\) states is ħω s, where ω s ≈ 2π × 1.45 GHz. b Distribution of magnetic energy density within a cross-section of the TE01δ mode supported by the cavity. White arrows indicate the magnetic field vector. c Region illuminated by optical pulse. The magnetic field directly maps to the single spin–photon coupling g s, for a cylindrical region of diameter 3 mm and height 4 mm, where the pentacene:p-terphenyl crystal resides. d Cartoon rendering of the cavity QED system. A 0.053% mol/mol pentacene-doped p-terphenyl crystal is housed within a hollow cylinder of strontium titanate inside a cylindrical copper enclosure. The fundamental TE01δ mode of the cavity is tuned to ~1.45 GHz, the transition frequency of the X and Z triplet sub-levels. The pentacene molecules are photo-excited by pulses from an optical parametric oscillator. Microwave power is coupled out from the cavity by a small antenna loop and directly recorded by a digital storage oscilloscope without amplification

The microwave magnetic energy-density (Fig. 1b) can be mapped directly to the single spin–photon coupling in the central region of the cavity housing the pentacene molecules (Fig. 1c). Within the region illuminated by the optical pulse, the single spin–photon coupling is g s/2π = 0.042 ± 0.002 Hz. An estimate of the ensemble spin–photon coupling strength is therefore \(g_{\mathrm{e}} \equiv g_{\mathrm{s}}\sqrt N \approx 2\pi \times 1.1\) MHz. The cavity mode decay rate (linewidth) was measured to be κ c = 2π × 0.18 MHz and the spin decoherence rate of the transition was taken from reported room-temperature free induction decay measurements of the spin dephasing time for samples of similar concentration, \(T_2^* = 2.9\) μs,21 yielding a rate of \(\kappa _{\mathrm{s}} = 2{\mathrm{/}}T_2^* \approx 2\pi \times 0.11\) MHz. The spin-lattice relaxation rate and decay rates of the triplet sub-levels back to the singlet ground state are at least an order of magnitude slower than the spin dephasing rate so can be neglected.22 Thus, the system is expected to be within the strong coupling regime since the predicted ensemble spin–photon coupling is an order of magnitude greater than both the cavity decay and spin dephasing rates, \(g_{\mathrm{e}} \gg \kappa _{\mathrm{c}},\kappa _{\mathrm{s}}\), with cooperativity \(C = 4g_{\mathrm{e}}^2{\mathrm{/}}\kappa _{\mathrm{c}}\kappa _{\mathrm{s}} \approx 250\).

Stimulated emission, due to the population inversion established by the optical pulse, amplifies the thermal cavity photon population \(\left( {\bar n\sim 4 \times 10^3} \right)\), resulting in a buildup of electromagnetic energy in the cavity, i.e., masing.23 The instantaneous (single-shot) microwave signal coupled out of the cavity, tuned to a frequency of ω c = 2π × 1.4495 GHz with an optical pulse of energy 15 mJ, is shown in Fig. 2. There is a short delay of the order of a microsecond until the microwave signal emerges, after which it oscillates with a period of around half a microsecond, whilst decaying at rate Γ over the course of 10 μs. Fourier analysis revealed a normal mode-splitting (Rabi frequency) of Ω = 2g e ≈ 2π × 1.8 MHz (see Fig. 2c), indicating that the cavity mode and collective spin state hybridise to form a collective spin–photon polariton and that the strong coupling condition is satisfied, with cooperativity C ~ 190. As the optical pump pulse energy was varied from 0 to 15 mJ to excite increasing numbers of pentacene molecules, the normal-mode splitting increased as \(\sqrt N\) as shown in Fig. 2d, confirming the ensemble spin–photon coupling scaling predicted by the Tavis–Cummings model for a spin-ensemble.13

Measurement of Rabi oscillations from photo-excited pentacene:p-terphenyl spin-ensemble coupled to the STO cavity. a Single-shot measurement of microwave output following optical pulse. The initial burst builds up from thermal photons and follows classical laws since the spin–spin correlation and spin–photon coherence has yet to build up. This was measured by directing the output microwave signal into an oscilloscope. b Instantaneous power of the output following optical pulse. The peak microwave output power is −6.8 dBm. Subsequent oscillations in the microwave power, with period ~0.55 μs and decay rate Γ, are due to the collective exchange of energy between the correlated ensemble Dicke state and the cavity mode. The blue line shows the expected decay of an empty cavity \(\left( { \propto e^{ - \kappa _{\mathrm{c}}t}} \right)\). c Fourier analysis of the signal for a cavity frequency of ω c = 2π × 1.4495 GHz and 15 mJ optical pulse energy reveals that ensemble spin-coupling has split the normal modes, yielding a Rabi frequency of \(\Omega \sim 2\pi \times 1.8\) MHz. d Increasing the laser pulse energy excites more pentacene molecules into spin-triplets and therefore increases the ensemble spin–photon coupling (and hence normal-mode Rabi splitting) with a \(\sqrt N\) dependence. This graph confirms that the square of the splitting is linearly dependent on the optical pump pulse energy and hence N

Discussion

For a single excitation on resonance (ω c = ω s), the eigenstates are a coherent superposition of two basis states: the spin mode and the cavity mode. If \(\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}}\) and \(\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}}\) = a † \(\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}}\) are the possible states of the cavity mode and \(\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\) and \(\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\) = a † \(\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\) are the possible states of the spin-mode, then the two eigenstates are \(\left| + \right\rangle = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}} + \left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}}} \right)\) and \(\left| - \right\rangle = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}} - \left| 0 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{s}}\left| 1 \right\rangle _{\mathrm{c}}} \right)\), separated in energy by ħΩ = 2ħg e. In this system, there are many more excitations so to describe the dynamical behaviour of the Dicke system we derived Lindblad master equations for the reduced spin–photon density matrix within the Born–Markov approximation.7,24,25 Here we used the Tavis–Cummings Hamiltonian and a Liouvillian that accounted for decoherence due to cavity decay, spin dephasing and spin-lattice relaxation. A system of coupled differential equations was derived for the expectation values of relevant variables using a cumulant expansion truncated to third-order26 (see Supplementary Information). The dynamical behaviour of the expectation values of the cavity photon population, spin–photon coherence, spin–spin correlation and inversion are shown in Fig. 3, where the photon population \(\bar n = \left\langle {a^\dagger a} \right\rangle\) is in excellent agreement with that inferred from the measured microwave power. The delay between photo-excitation and the emergence of the first microwave burst is due to a prolonged period of stimulated emission since the number of excitations in the initial spin inversion (~1015) greatly exceeds the number of thermal photons in the cavity mode (~103). This period of stimulated emission results in a microwave photon burst where the cavity mode photon population has similar magnitude to the number of spins N. It is also accompanied by a build-up of the spin–spin correlation \(\left\langle {\tilde S^ + \tilde S^ - } \right\rangle\). The spins are not correlated initially but through stimulated emission of photons into the cavity mode they become increasingly correlated, leading to the establishment of a macroscopic collective spin–photon polariton. The maximum expectation value of the modelled spin–spin correlation, \(\left\langle {\tilde S^ + \tilde S^ - } \right\rangle {\mathrm{/}}N \approx 0.15\) is close to the theoretical maximum of 0.25.1 The discrepancy is mostly due to the imperfect initialisation of the spin population polarisation. The collective spin–spin correlation \(\left\langle {\tilde S^ + \tilde S^ - } \right\rangle\) also reveals the degree of transient multipartite entanglement within the symmetric Dicke states. The entanglement resulting from the ambiguity in being able to assign emission or absorption of photons to specific spins. For the N = 2 case, the maximally entangled \(\left( {\left| {e,g} \right\rangle + \left| {g,e} \right\rangle } \right){\mathrm{/}}\sqrt 2\) state is a Bell state. Once the collective polariton emerges there is coherent oscillatory exchange of excitations with the cavity mode at the Rabi frequency Ω, persisting for up to 10 μs.

Modelled dynamics using master equations. a The expectation value of the cavity photon number \(n = \left\langle {a^\dagger a} \right\rangle\), agrees well with the inferred population from measurement of the microwave power. b Negative values of the spin–photon coherence \(\left\langle {a^\dagger \tilde S^ - } \right\rangle\) correspond to exchange of excitations from the collective spins to the cavity mode and positive values from the cavity mode to the collective spins. c The spin–spin correlation \(\left\langle {\tilde S^ + \tilde S^ - } \right\rangle\), a measure of the degree of multipartite entanglement of the spins, is maximal when the inversion is zero. d The inversion \(\left\langle {\tilde S^z} \right\rangle\), initially at 0.8, stays fairly constant until the emergence of the first microwave burst. It subsequently oscillates through the Rabi cycles, coming to rest in a negative yet still spin-polarised state, where the majority of electrons reside in the lower \(\left| g \right\rangle\) state

The collective spin–photon polariton decay rate Γ as a function of Rabi frequency (for optical pump pulses in the 0–10 mJ range) is shown in Fig. 4. Above maser threshold where the cooperativity C > 1 and below the strong coupling regime threshold, the decay rate Γ increases until the Rabi frequency is equal to the sum of the cavity decay and spin decoherence rates, \(\Omega = 2g_{\mathrm{e}}\sim \kappa _{\mathrm{c}} + \kappa _{\mathrm{s}}\) and the decay rate \(\Gamma \sim \left( {\kappa _{\mathrm{c}} + \kappa _{\mathrm{s}}} \right){\mathrm{/}}2\). As the Rabi frequency (and ensemble spin–photon coupling) increases and the system goes further into the strong-coupling regime, the ensemble spin–photon polariton decay rate Γ begins decreasing asymptotically towards half the cavity decay rate, κ c/2, implying that the spin dephasing rate is suppressed. This so-called “cavity protection” effect, associated with non-Markovian memory effects, is attributed to inhomogeneous broadening of spin transitions with non-Lorentzian lineshapes.10,11,12

Cavity protection effect. The vertical dashed lines marks the onset of masing (where the cooperativity C > 1) and the strong coupling regime where Ω = 2g e > κ c + κ s, the Rabi frequency exceeds the sum of cavity decay and spin decoherence rates. As the Rabi frequency increases, Γ, the decay rate of the collective spin–photon polariton decreases, asymptotically approaching half the cavity decay rate κ c/2 (horizontal dashed line), with the assumption that the single spin decoherence rate is zero. The colour shading distinguishes the weak (red) and strong (green) coupling regimes

To conclude, this system, which was recently used to demonstrate a solid-state room-temperature maser,19,20,23 also shows promise as a platform for exploring cavity quantum electrodynamics, spin memories for quantum information processing16 and quantum-enhanced technologies for metrology, sensing and communications.27

Methods

Experimental setup

The cavity was constructed from a hollow cylindrical single-crystal of STO containing a 0.053% pentacene-doped p-terphenyl crystal (diameter 3 mm, height 8 mm). The STO cylinder was placed upon a cylindrical sapphire disc and housed within a cylindrical copper enclosure. The cavity was directly coupled to a digital storage oscilloscope with 50 Ω impedance (Keysight MSOX6004 A, 20 GSa/s sampling-rate, 6 GHz bandwidth) using a small loop antenna with coupling coefficient, k = 0.2. An additional weakly coupled (−35 dB) antenna, directional coupler (−20 dB) and amplifier (40 dB) allowed transmission measurements of the cavity to made using a vector network analyser (Agilent 8520E), revealing the resonant frequency and loaded quality-factor (Q) of the TE01δ mode to be \(\omega _{\mathrm{c}}\sim 2\pi \times 1.45\) GHz and 8,500 respectively. A Nd:YAG pumped OPO (Continuum Surelite Plus SL I-20) generated 592 nm wavelength optical pulses of 5.5 ns duration and energy up to 15 mJ at a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The optical pump pulse energies were measured using a beam splitter and an optical energy metre (Gentec-EO Maestro). The expectation value of the photon number as a function of time was extracted from the measured microwave power P(t) using the expression \(\bar n(t) = \left\langle {a^\dagger a} \right\rangle = P(t)(1 + k){\mathrm{/}}\hbar \omega _{\mathrm{c}}\kappa _{\mathrm{c}}k,\) where k is the coupling coefficient (k = 0.2), ħ is the reduced Planck constant and ω c and κ c the cavity frequency and decay rate respectively.

Crystal growth

The pentacene:p-terphenyl crystal was grown as per the previously reported method19,20 but with higher concentration of pentacene (see Supplementary Information for details).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the finding of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Haroche, S. & Raimond, J.-M. Exploring the quantum: Atoms, cavities, and photons (Oxford, New York, 2006).

Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 93, 99 (1954).

Baumann, K., Guerlin, C., Brennecke, F. & Esslinger, T. Dicke quantum phase transition with a superfluid gas in an optical cavity. Nature 464, 1301–1306 (2010).

Pustovit, V. N. & Shahbazyan, T. V. Cooperative emission of light by an ensemble of dipoles near a metal nanoparticle: the plasmonic Dicke effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 077401 (2009).

Zhu, X. et al. Coherent coupling of a superconducting flux qubit to an electron spin ensemble in diamond. Nature 478, 221–224 (2011).

Sandner, K. et al. Strong magnetic coupling of an inhomogeneous nitrogen-vacancy ensemble to a cavity. Phys. Rev. A 85, 053806 (2012).

Meiser, D., Ye, J., Carlson, D. & Holland, M. Prospects for a millihertz-linewidth laser. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 163601 (2009).

Bohnet, J. G. et al. A steady-state superradiant laser with less than one intracavity photon. Nature 484, 78–81 (2012).

Norcia, M. A., Winchester, M. N., Cline, J. R. & Thompson, J. K. Superradiance on the millihertz linewidth strontium clock transition. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601231 (2016).

Diniz, I. et al. Strongly coupling a cavity to inhomogeneous ensembles of emitters: potential for long-lived solid-state quantum memories. Phys. Rev. A 84, 063810 (2011).

Krimer, D. O., Putz, S., Majer, J. & Rotter, S. Non-markovian dynamics of a single-mode cavity strongly coupled to an inhomogeneously broadened spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. A. 90, 043852 (2014).

Putz, S. et al. Protecting a spin ensemble against decoherence in the strong-coupling regime of cavity QED. Nat. Phys. 10, 720–724 (2014).

Tavis, M. & Cummings, F. W. Exact solution for an N-molecule radiation-field Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. 170, 379 (1968).

Yoshie, T. et al. Vacuum rabi splitting with a single quantum dot in a photonic crystal nanocavity. Nature 432, 200–203 (2004).

Purcell, E. Spontaneous emission probabilities at radio frequencies. Phys. Rev. 69, 681 (1946).

Amsüss, R. et al. Cavity QED with magnetically coupled collective spin states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 060502 (2011).

Sloop, D. J., Yu, H., Lin, T. & Weissman, S. I. Electron spin echoes of a photoexcited triplet: Pentacene in p-terphenyl crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 75, 3746 (1981).

Takeda, K., Takegoshi, K. & Terao, T. Zero-field electron spin resonance and theoretical studies of light penetration into single crystal and polycrystalline material doped with molecules photoexcitable to the triplet state via intersystem crossing. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 4940–4946 (2002).

Breeze, J. et al. Enhanced magnetic Purcell effect in room-temperature masers. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–6 (2015).

Salvadori, E. et al. Nanosecond time-resolved characterization of a pentacene-based room-temperature maser. Sci. Rep. 7, 41836 (2017).

Yang, T.-C., Sloop, D., Weissman, S. & Lin, T.-S. Zero-field magnetic resonance of the photo-excited triplet state of pentacene at room temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 11194–11201 (2000).

Yu, H.-L., Lin, T.-S., Weissman, S. & Sloop, D. J. Time resolved studies of pentacene triplets by electron spin echo spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 80, 102–107 (1984).

Oxborrow, M., Breeze, J. & Alford, N. Room-temperature solid-state maser. Nature 488, 353–356 (2012).

Carmichael, H. J. Statistical Methods in Quantum Optics 1: Master Equations and Fokker-Planck Equations (Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 2003).

Henschel, K., Majer, J., Schmiedmayer, J. & Ritsch, H. Cavity QED with an ultracold ensemble on a chip: Prospects for strong magnetic coupling at finite temperatures. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033810 (2010).

Kubo, R. Generalized cumulant expansion method. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 17, 1100–1120 (1962).

Hosten, O., Krishnakumar, R., Engelsen, N. & Kasevich, M. Quantum phase magnification. Science 352, 1552–1555 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ke-Jie Tan for supplying the pentacene:p-terphenyl crystal and Andrew Horsfield, Stuart Bogatko, Benjamin Richards and Myungshik Kim for useful discussions. This work was supported by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council through grants EP/K011987/1 (IC) and EP/K011804/1 (UCL). We also acknowledge support from the Henry Royce Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Experiments were performed by J.D.B., E.S., J.S. and C.W.M.K. Data was processed by J.D.B. and C.W.M.K. Theory was developed by J.D.B. who also performed simulations of quantum master equations, optical pulse penetration and cavity design. The paper was written by J.D.B., assisted by C.W.M.K. and with additional editing by E.S. and N.M.A. The study was conceived by J.D.B., E.S., N.M.A. and C.W.M.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Breeze, J.D., Salvadori, E., Sathian, J. et al. Room-temperature cavity quantum electrodynamics with strongly coupled Dicke states. npj Quantum Inf 3, 40 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0041-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0041-3

This article is cited by

-

Strong coupling between colloidal quantum dots and dielectric film at room temperature

Applied Physics B (2024)

-

Spectral engineering of cavity-protected polaritons in an atomic ensemble

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Microwave mode cooling and cavity quantum electrodynamics effects at room temperature with optically cooled nitrogen-vacancy center spins

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Pentacene in 1,3,5-Tri(1-naphtyl)benzene: A Novel Standard for Transient EPR Spectroscopy at Room Temperature

Applied Magnetic Resonance (2022)

-

Cavity-enhanced microwave readout of a solid-state spin sensor

Nature Communications (2021)