Abstract

We realize a two-qubit sensor designed for achieving high-spectral resolution in quantum sensing experiments. Our sensor consists of an active “sensing qubit” and a long-lived “memory qubit”, implemented by the electronic and the nitrogen-15 nuclear spins of a nitrogen-vacancy center in diamond, respectively. Using state storage times of up to 45 ms, we demonstrate spectroscopy of external ac signals with a line width of 19 Hz (∼2.9 ppm) and of carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance signals with a line width of 190 Hz (∼74 ppm). This represents an up to 100-fold improvement in spectral resolution compared to measurements without nuclear memory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum sensors based on nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond show promise for a number of fascinating applications in condensed matter physics, materials science, and biology.1, 2 By embedding them in a variety of nanostructures, such as tips,3,4,5,6 nanocrystals,7 or surface layers,7, 8 local properties of samples can be investigated with high sensitivity and spatial resolution. In particular, diamond chips with near-surface NV centers have enabled pioneering experiments in nanoscale detection of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), potentially enabling structural analysis of individual molecules with atomic resolution.9,10,11

A key feature of many quantum sensing experiments is the ability to record time-dependent signals and to reconstruct their frequency spectra. The canonical approach uses dynamical decoupling sequences, which are sensitive to frequencies commensurate with the pulse spacing while efficiently rejecting most other frequencies.12,13,14,15,16 The spectral resolution of dynamical decoupling spectroscopy, however, is Fourier-limited by decoherence to ~(πT 2)−1 ∼ 10–100 kHz for shallow NV centers,17 where T 2 is the electronic decoherence time. It has recently been recognized that by correlating two consecutive decoupling sequences, separated by a variable waiting time t, the spectral resolution can be extended to the inverse state life time T 1, which can be 10–100× longer than T 2 (refs. 18, 19). Correlation spectroscopy has been applied to both generic ac magnetic fields and to nuclear spin detection, and spectral resolutions of a few 100 Hz have been demonstrated.20,21,22

Despite these impressive advances, there is a strong motivation to further extend the spectral resolution. For example, many proposed nanoscale NMR experiments9,10,11 require discrimination of fine spectral features, often in the few-Hz range. In addition, atomic-scale mapping of nuclear spin positions strongly relies on precise measurements of NMR frequencies and hyperfine coupling constants.22 Therefore, methods to acquire frequency spectra with even higher spectral resolution are highly desirable.

In this study, we implement a two-qubit sensor designed to further refine the spectral resolution by a factor of 10–100×. Our two-qubit sensor consists of an active sensing qubit and an auxiliary memory qubit, formed by the electronic spin and the 15N nuclear spin of the NV center in diamond. By intermittently storing the state information in the nuclear—rather than electronic—spin qubit, we extend the maximum waiting time t from T 1 ~ 1 ms to the nuclear T 1,n > 50 ms, with a corresponding gain in spectral resolution. In addition, we use the nuclear memory to enhance sensor readout efficiency through repeated readout,23, 24 which would otherwise result in untenably long acquisition times. The presented two-qubit system is particularly useful because it is intrinsic to the NV center, with no need for additional sensor engineering.

The advantages of one or more “auxiliary” qubits have been recognized in several different contexts, including the quantum logic clock for enhanced atomic clock performance25,26,27 and resettable auxiliary qubit(s) for emulating the environment in quantum simulation.28, 29 Multi-qubit probes may also assist the detection of cross-correlations in environmental noise30 or the study of non-classical dynamics.31 In recent experiments with spin qubits in diamond, auxiliary nuclear spins have been used to increase the effective coherence time of an electronic sensor spin by quantum error correction,32 quantum feedback,33, 34 or by exploiting double-quantum coherence.35 Moreover, ancillary nuclei have been used to enhance the readout efficiency.23, 24 In our study we utilize the auxiliary nuclear spin as a long-lived memory for the electron qubit’s state.

Results

Implementation of the nuclear spin memory

Our two-qubit sensor exploits the four-level system formed by the m S ∈ {0, −1} subspace of the S = 1 electronic spin and the two m I ∈ {−1/2, +1/2} states of the I = 1/2 nuclear spin. This pair has four allowed spin-flip transitions (Fig. 1). Due to the hyperfine interaction (a || = 2π × 3.05 MHz), all four transitions are spectrally resolved and can be addressed individually using frequency-selective microwave (MW) or rf pulses. Driving a selective \(R_X^\pi\) rotation on either of theses transitions leads to a conditional inversion, depending on the state of the other spin. This realizes controlled-NOT gates on the electronic and nuclear spins, respectively, which we denote by c-NOTe and c-NOTn. The specific transitions used in our study are indicated in Fig. 1b.

Experimental arrangement. a Atomistic picture of the 15NV− two-spin system, showing the NV center’s electronic spin (red) and 15N nuclear spin (blue). Distant 13C nuclei, which produce measurable NMR signals, are also shown. Experiments are carried out on a single-crystal diamond chip with a shallow (3−10 nm) layer of NV centers created by ion implantation. b Energy level diagram in the electronic ground state showing four resolved spin-flip transitions. In a typical bias field of 320 mT, aligned with the NV symmetry axis, the electron spin transition frequencies are ω mw,1 = 6097 MHz and ω mw,2 = 6100 MHz, and the nuclear spin transition frequencies are ω rf,1 = 1.381 MHz and ω rf,2 = 1.669 MHz, respectively. The transitions used in our study are ω mw,1 (red) and ω rf,1 (blue). Control pulses are applied via a coplanar waveguide connected to two separate arbitrary waveform generators (see Methods section)

To implement the “store” and “retrieve” operations, we combine a c-NOTe gate and c-NOTn gate (dashed boxes in Fig. 2). Assuming the electronic spin is initially in the \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) state and the nuclear spin in an idle (unspecified) state \(\left| {{\alpha _{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\), the effect of the two gates is \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{\alpha _{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle \mathop{\longrightarrow}\limits^{{{\rm{c}} - {\rm{NO}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{e}}}}}{\left\langle {0{\rm{|}}\alpha } \right\rangle _{\rm{n}}}\left| {{1_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{0_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\) + \({\left\langle {1{\rm{|}}\alpha } \right\rangle _{\rm{n}}}\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{1_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle \mathop{\longrightarrow}\limits^{{{\rm{c}} - {\rm{NO}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{n}}}}}{\left\langle {0{\rm{|}}\alpha } \right\rangle _{\rm{n}}}\left| {{1_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{0_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\) + \({\left\langle {1{\rm{|}}\alpha } \right\rangle _{\rm{n}}}\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{0_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle = \left| {\alpha _{\rm{e}}^\prime } \right\rangle \left| {{0_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\), where \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{\alpha _{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\) etc. denote product states. Likewise, if the electronic spin is initially in the \(\left| {{1_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) state, \(\left| {{1_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle \left| {{\alpha _{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle \mathop{\longrightarrow}\limits^{{{\rm{c}} - {\rm{NO}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{n}}}}\ {{\rm{c}} - {\rm{NO}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{e}}}}}\left| {\alpha _{\rm{e}}^\prime } \right\rangle \left| {{1_{\rm{n}}}} \right\rangle\). As a result, the state of the electronic spin is stored in the state of the nuclear spin. To retrieve the state, the order of the c-NOT gates simply needs to be reversed (Fig. 2). Alternatively, the state can also be retrieved by initializing the electronic spin followed by a single c-NOTe gate (dotted box in Fig. 2). Advantages of the single-gate retrieval are that it is fast (because no c-NOTn is involved) and that it can be repeated many times.23, 24, 36 A disadvantage is a reduced contrast due to NV charge state conversion37 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the implementation of the quantum spectrum analyzer discussed below, we therefore use a two-gate retrieval during the signal correlation period t and a single-gate retrieval for improving readout efficiency.

Implementation of the memory-assisted spectroscopy protocol for detecting alternating signals V(t). a Qubit gate diagram. The core of the protocol are two-phase gates \(R_Z^{{\Phi _1}}\) and \(R_Z^{{\Phi _2}}\) that are separated by a variable waiting time t, where Φ1 ∝ V(t A) and Φ2 ∝ V(t C). The long-lived memory qubit allows extending the waiting t, which greatly enhances the Fourier-limited resolution of the spectroscopy protocol. In addition, the memory qubit can be used to improve detection efficiency by a factor of ~n through repeated readouts. b Pulse timing diagram. Laser pulses are shown in green, microwave pulses in red, radio frequency pulses in blue, and the photon detector gate in a black contour. The two-phase measurements are implemented by XY8 sequences52 with N = 8 or N = 32 pulses and τ ≈ 1/(2f ac), where f ac is the expected signal frequency

We assess the performance of the nuclear spin memory under a set of store, retrieve, and hold operations. To characterize the efficiency of the store and retrieve operations, we perform selective Rabi rotations on all four spin-flip transitions, and find efficiencies >90% for c-NOTe and 60–80% for c-NOTn, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The memory access time is between 20 and 50 μs for the double c-NOT implementation, limited by the duration of the rf pulse, and ~2 μs for the single c-NOT implementation. We further test the complete memory by performing an electronic Rabi oscillation, storing the result in the nuclear memory, clearing the electronic qubit by an initialization step, and retrieving the Rabi signal (Supplementary Fig. S2). Lastly, we assess the memory hold time—given by the nuclear T 1,n—in the absence and presence of laser illumination, with typical values of T 1,n ≈ 52 ms (no laser) and T 1,n ≈ 1.2 ms (under periodic readout) at a bias field of 320 mT. This bias field supports n ~ 1000 non-destructive readouts of the memory (dotted box in Fig. 2) before the nuclear spin becomes repolarized36 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Implementation of the quantum spectrum analyzer

We compose the full spectroscopy protocol from a correlation sequence19, 22 and several storage and retrieval operations (Fig. 2). In a first step, we initialize the electronic sensor spin into the \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) state. An initial phase measurement is then performed using a multipulse sensing sequence approximately tuned to the frequency f ac of the ac field (Fig. 2b). During the multipulse sequence, the ac signal \(V(t) = {V_0}\,{\rm{cos}}\left( {2\pi {f_{{\rm{ac}}}}t} \right)\) imprints a phase Φ1 ∝ V(t A) on the electronic qubit, leaving it in a superposition \(\left| {{\psi _{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) of states \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) and \(\left| {{1_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) with a probability amplitude \({\left\langle {0{\rm{|}}\psi } \right\rangle _{\rm{e}}} = {\textstyle{1 \over 2}}\left( {1 + {\rm{sin}}\,{\Phi _1}} \right)\). Next, we store \(\left| {{\psi _{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) in the nuclear memory, wait for a variable delay time t (which can be longer than the electronic T 1 time), and read it back. A second-phase measurement is then used to acquire a further phase Φ2 ∝ V(t C). In a last step, we read out the final state of the electronic qubit via storing it in the nuclear memory and performing n periodic readouts. By averaging the protocol over many repetitions, the probability p = |〈0|ψ〉e|2 of finding the sensor in the initial state \(\left| {{0_{\rm{e}}}} \right\rangle\) can be precisely estimated.

Because Φ1 and Φ2 depend on the relative phase of the ac signal V(t), the total phase acquired by the qubit oscillates with f ac. As detailed in the Methods section, the resulting state probability p(t) then also oscillates with f ac,

where we assume that the ac signal is not synchronized with the acquisition. Equation (2) is for small signals where \({\rm{sin}}\,{\Phi _1} \approx {\Phi _1}\) and \({\rm{sin}}\,{\Phi _2} \approx {\Phi _2}\), resulting in an oscillation amplitude \({p_0} \approx 2\gamma _{\rm{e}}^2V_0^2t_{{\rm{meas}}}^{\rm{2}}{\rm{/}}{\pi ^2},\) where t meas = t B − t A = t D − t C (Fig. 2). In order to obtain a frequency spectrum of V(t), we can therefore simply measure p(t) for a series of t values followed by a Fourier transform. Crucially, the spectral resolution is only limited by the duration t of the correlation measurement, which can now be as long as the nuclear memory time T 1,n. Since the nuclear memory time typically far exceeds both the electronic decoherence time T 2 and relaxation time T 1, a much finer spectral resolution can be expected compared to dynamical decoupling or standard correlation spectroscopy.

High-resolution spectroscopy of ac signals

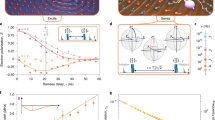

We demonstrate the performance of the memory-enhanced spectrometer for two experimental scenarios. In a first experiment, we expose the sensor to an external ac test signal with a nominal frequency of f ac = 6.626070 MHz and an amplitude of V 0 ≈ 90 μT. The test signal is produced on an auxiliary function generator not synchronized with the acquisition, and coupled into the same waveguide structure used for spin control. Two measurements are carried out: in a first acquisition (Fig. 3a) we perform a regular spectroscopy measurement without the nuclear memory. We can clearly observe an oscillation in the time trace due to the ac signal. The signal decays on a time scale of ~0.5 ms, limited by the electronic T 1 of this NV center. In Fig. 3b we repeat the measurement, now making use of the nuclear memory. The oscillation persists beyond t = 45 ms, overcoming the limitation due to the electronic T 1 by almost two orders of magnitude.

High-resolution spectra of external ac test signals. a Time trace recorded from an ac test signal without using the nuclear memory qubit. A rapid decay of the signal is observed due to the electronic T 1 decay. b Time trace recorded from the same signal using the nuclear memory qubit. The signal barely decays up to t = 45 ms. Datapoints are sampled at a rate of 3.45 kHz, corresponding to an undersampling by 1925×. c Fourier transform (power spectrum) of the time traces from a and b. Inset shows a zoom-in for b. Dots are the data and dashed lines are fits. All line widths are full width at half maximum. d Nuclear memory-assisted spectrum of two artificial signals with fitted peak frequencies of 6.62611579(12) MHz and 6.62632107(6) MHz. The associated time trace is given in Supplementary Fig. S4. Total acquisition time per spectrum was on the order of 48 h

Fourier spectra of the two time signals (Fig. 3c) show that the peak width reduces from 1.3 kHz (200 ppm) without memory to 20 Hz (3.0 ppm) with memory. This corresponds to an improvement in spectral resolution by ~×65. Figure 3d shows a second example of nuclear memory-assisted spectroscopy, where two ac test signals separated by about 0.2 kHz are applied. Both peaks can be clearly distinguished, demonstrating that the method is effective in precisely resolving spectral features. A narrow line width of only 19 Hz (~2.9 ppm) is observed, and peak positions are defined with eight digits of precision. The absolute accuracy of the frequency measurement is governed by the internal clock of the MW pulse generator.

The spectral resolution in Fig. 3c, d is limited by the memory hold time given by the nuclear T 1,n, here ~52 ms. Since the nuclear relaxation is dominated by a flip-flop process with the NV center’s electron spin and slows down for higher bias fields,36 there is scope for an additional improvement in spectral resolution at Tesla bias fields.38

High-resolution 13C NMR spectroscopy

We further apply the two-qubit sensor to detect NMR spectra from nearby 13C nuclear spins that are naturally present at ~1% in the diamond chip. This experiment represents an important test case toward the detection of more complex NMR spectra, such as those from molecules deposited on the chip.17, 39, 40 The detection of NMR signals is considerably more involved compared to external ac signals, because the sensor can affect the 13C nuclear spin precession during t via the hyperfine interaction. In addition, NMR spectroscopy is known to be very sensitive to drifts in the external bias field.

Figure 4 shows a set of four NMR spectra recorded from the same 13C nuclear spin using the memory-assisted spectroscopy protocol. The four panels represent increasing refinements in spectrum acquisition. Figure 4a shows an initial 13C spectrum that displays features over a wide frequency range of several kHz (~1000 ppm). We find these features to be linked to small changes in the bias field, probably caused by temperature-induced drifts in the magnetization of the permanent magnet in our set up. By carefully tracking the electron spin resonance during the experiment and using post-correction, these drifts can be eliminated (Fig. 4b). Further details are given in the Methods section and Supplementary Fig. S5.

NMR spectra (power spectra) of a nearby carbon-13 nuclear spin at a bias field of 245.8 mT. a Initial spectrum before correcting for NMR frequency drift. b Same as a, after correcting for frequency drift. N = 7 dynamical decoupling pulses are applied to the m S = 0 ↔ −1 transition of the electronic sensor spin. c Same as b, with a decoupling pulse applied every 4 μs. The line width of 190 Hz corresponds to ~74 ppm. d Same as b, where the electronic sensor spin is periodically re-pumped into m S = 0 by N = 6 laser pulses. The maximum t time is between 3 and 4 ms and the electronic T 1 is 1.4 ms. Hyperfine coupling parameters are \({a_\parallel } = - 2\pi \times 138.9\,{\rm{kHz}}\) and a ⊥ = 2π × 120.55 kHz, respectively. Fitted peak frequencies are 2.5554139(14) MHz for b, 2.5577836(12) MHz for c, and 2.6300221(43) kHz for d. The peak frequencies for a–c are shifted from d by a ||/222

The remaining line width of the 13C resonance is ~220 Hz, which corresponds to a dephasing time of \(T_{{{2,}^{{\rm{13}}}}{\rm{C}}}^ * \approx 1{\rm{/}}\left( {\pi \times 220\,{\rm{Hz}}} \right) \approx 1.4\,{\kern 1pt} {\rm{ms}}\). Because the dephasing time is very similar to the relaxation time T 1 ~ 1.4 ms of this NV center, the 13C dephasing is most likely dominated by the hyperfine interaction with the electronic spin. Thus, even if our spectrometer is technically capable of achieving a ×10 better spectral resolution, this improvement does not carry over to the 13C spectrum because of dephasing.

In an attempt to extend the 13C dephasing time and further reduce the 13C NMR line width, we have explored several decoupling protocols, neither of which turned out to be effective. A first protocol (Fig. 4b) includes a series of π pulses that are applied to the m S = 0 ↔ −1 transition during the free evolution time t. This protocol suppresses the hyperfine interaction with the electronic m S = −1 state. However, this protocol does not decouple the interaction with the m S = +1 state, and only a marginal improvement can be expected. Indeed, no significant change is observed in the 13C line width without and with dynamical decoupling even when using many hundred decoupling pulses (Fig. 4c). A more effective approach would be to simultaneously decouple both the m S = 0 ↔ −1 and m S = 0 ↔ +1 transitions using double-frequency irradiation,41 but this control is not currently supported by our hardware. Instead, we use a series of laser pulses to periodically repolarize the NV center into the m S = 0 state (Fig. 4d) or the m S = −1 state (data not shown). No narrowing of the 13C resonance is observed with either protocol. There are two possible explanations for the observations made in Fig. 4b–d: Either the decoupling is ineffective due to the relatively strong hyperfine coupling, and the \(T_{{{2,}^{{13}}}{\rm{C}}}^ *\) dephasing is still dominated by the hyperfine interaction. This hypothesis is supported by a numerical simulation (Supplementary Fig. S6). Alternatively, the measured \(T_{{{2,}^{{\rm{13}}}}{\rm{C}}}^ *\) dephasing time represents the intrinsic 13C decoherence time due to nuclear dipole–dipole interactions within the 13C bath. This scenario is less likely because the expected decoherence time is of order ~10 ms (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Discussion

In summary, we implemented a two-qubit quantum sensor based on the electronic and 15N nuclear spins in diamond. By operating the nuclear spin as a long-lived memory qubit, we achieve exceptionally high-spectral resolution, with a best effort of 19 Hz or 2.9 ppm. The 15N spin forms a particularly suitable memory qubit because the nucleus is a natural part of the NV center, and because long storage times are possible combined with rapid memory access. Looking forward, we note that the implemented spectroscopy protocol entails several interesting opportunities for further refinements, especially toward application in nanoscale NMR and for realizing larger quantum registers. Active manipulation of both nuclei during the waiting time could, for example, be used to individually address a large number of weakly coupled 13C spins.42 Advanced NMR concepts, such as multi-dimensional spectroscopy22, 43 or spectral editing could be used to study interactions between nuclei.44 These concepts will likely require compressed sensing methods11, 45 and efficient NV readout23, 46 to accelerate data collection. Implementation of these techniques will be the key for performing structural analysis of single molecules, especially if larger biomolecules are to be targeted.

Note added

Recently, we became aware of related work describing quantum sensing with a nuclear memory qubit.35, 38, 42, 47 The work of refs. 35, 47 use the nuclear memory in a coherent state. This approach has the advantage of conserving the full phase information, but is limited by the T 2,n time (rather than the T 1,n) of a 15N nuclear memory and requires NMR pulses on the target 13C nuclei. By contrast, our approach is limited by T 1,n and does not require 13C NMR pulses. The work of ref. 38 describes both T 2,n and T 1,n storage but also requires NMR pulses. The works of ref. 42 and also ref. 19 describe a nuclear memory that is similar to our implementation, but use different schemes for the state SWAP and target 13C manipulation during coherent evolution, and no memory-assisted electron spin readout.

Methods

Diamond chips

Two different single-crystal diamond chips were used in the study. Sample A was an electronic-grade, natural abundance (1.1% 13C) plate with a shallow NV layer created by 5 keV 15N+ ion implantation and an 800 °C annealing step. The average NV center depth was 8 nm according to SRIM simulations. Sample B was an electronic-grade, isotopically pure (<0.01% 13C) plate with a similar NV layer as sample A. Except for providing proximal 13C nuclei for the NMR experiments, the higher 13C concentration of sample A compared to sample B played no role in any of the measurements. In particular, the 13C concentration had no influence on the electronic and 14N spin relaxation times relevant for our study. To further reduce the NV-center-to-surface distance, sample B was subjected to an oxygen etch at ~550 °C (ref. 17). The average NV center depth was 3−5 nm. Both samples were baked at 465 °C in air before experiments to clean the surface.

Measurement apparatus

The measurement apparatus consists of a home-built confocal microscope with 532 nm laser excitation and 630–800 nm fluorescence detection using a single photon counter module. The confocal microscope is equipped with a patterned, 50−100 μm-wide coplanar waveguide transmission line for producing MW and radio frequency magnetic control pulses at the sample location. Timing of experiments is controlled by the digital marker channels of a Tektronix AWG 5002 arbitrary waveform generator. Photons are analyzed by time tagging arrival times and correlating them with the timing of the pulse sequence. In addition, the microscope is equipped with a permanent NdFeB magnet to produce bias fields of up to ~400 mT. The direction of the vector magnetic field is aligned via a mechanical xyz stage.

To control the electronic and nuclear spin transitions of the NV center, separate MW and radio frequency channels are used, respectively. MW pulses are generated on the arbitrary waveform generator at a 100 MHz carrier and upconverted to the desired GHz frequency using a local oscillator (Quicksyn FSW-0020) and a single-sideband mixer (Marki MW IQ-1545). For the radio frequency pulses, a National Instruments NI PCI 5421 arbitrary waveform generator is used, which directly synthesizes the desired pulses without a mixing step. The two signals are amplified separately and then combined using a bias-T (Meca) before being connected to the MW transmission line. The output of the transmission line is terminated in a 50 Ω load. With this arrangement, typical Rabi frequencies of 20−30 MHz for the electron spin and 10−30 kHz for the 15N nuclear spin could be achieved. We observed that the Rabi frequency of the 15N nuclear spin was significantly enhanced by the hyperfine interaction.48

Store and retrieve operations

Storage and retrieval operations are implemented by selective pulses on one of the two resolved hyperfine lines. Square-shaped pulses are used for both electronic and nuclear spin manipulations. Selective MW pulses have a typical duration of 700 ns corresponding to a Rabi frequency of ~0.7 MHz. Selective rf pulses have a duration between 20 and 50 μs depending on the set up and NV center. A delay of 1−2 μs is added after every radio frequency pulse due to amplifier ringing. Rabi oscillations used to calibrate the selective pulses are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Correlation spectroscopy

Correlation spectroscopy18,19,20,21,22 correlates the outcomes of two subsequent sensing periods to obtain high-resolution spectra of time-dependent signals. In the present experiment, the method is implemented by subdividing a multipulse sequence into two equal periods of duration t meas = t B − t A = t D − t C that are separated by an incremented free evolution period t (Fig. 2). Since the multipulse sequence is phase sensitive, constructive or destructive phase build-up occurs between the two sequences depending on whether the free evolution period t is a half multiple or full multiple of the ac signal period T ac = 1/f ac. The final transition probability p oscillates with t as

where Φ1 and Φ2 are the phases accumulated by the electronic spin during the first and second measurement period, respectively. The approximation is for weak signals where \({\rm{sin}}\left( {{\Phi _1}} \right) \approx {\Phi _1}\) and \({\rm{sin}}\left( {{\Phi _2}} \right) \approx {\Phi _2}\). For strong signals, higher harmonics appear in the correlation spectrum and the amplitude of the correlation signal does not directly reflect the amplitude of the ac signal any longer.49

For an ac signal \(V(t) = {V_0}\,{\rm{cos}}\left( {2\pi {f_{{\rm{ac}}}}t + \phi } \right)\) whose period T ac = 2τ is commensurate with the pulse spacing τ of the multipulse sequence, the phase Φ1 is given by

where y(t′) = (−1)[t′/τ] is the modulation function50, 51 of the sequence and N = t meas/τ is the number of pulses. This integral evaluates to

Likewise, the phase Φ2 evaluates to

In our experiments, the ac signal is not synchronized with the detection sequence, such that the phase ϕ is arbitrary. Therefore, the observed correlation signal p(t) is an average over ϕ = 0...2π. For the small signal approximation this leads to

where we have set t A = 0 in the third step and used that \({\rm{cos}}\left( {2\pi {f_{{\rm{ac}}}}{t_{\rm{C}}}} \right) = {\rm{cos}}\left( {2\pi {f_{{\rm{ac}}}}\left[ {{t_{\rm{A}}} + {t_{{\rm{meas}}}} + t} \right]} \right) = {\rm{cos}}\left( {2\pi {f_{{\rm{ac}}}}t} \right)\). Here, \({p_0} = 2\gamma _{\rm{e}}^2V_0^2t_{{\rm{meas}}}^2{\rm{/}}{\pi ^2}\) is the amplitude of the correlation signal.

Tracking and post-correction of spectral drift

When performing NMR experiments, we noticed considerable drifts, often several kHz, in the 13C nuclear transition frequency. Such frequency drifts are a well-known problem in high-resolution NMR spectroscopy, as they lead to unwanted line broadening. Frequency drifts are typically caused by drifts in the static magnetic field; in our case, this is likely due to a temperature-related change of the magnetization of the permanent magnet.

We have implemented a tracking and post-correction scheme to eliminate the frequency drifts. To follow the drift in magnetic field, we track the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) resonance of the NV center during long-term measurements as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The difference between measured EPR frequency ω e and reference EPR frequency ω e,0 corresponds to a drift in field by ΔB = (ω e − ω e,0)/γ e where γ e = 2π × 28 GHz/T is the electron gyromagnetic ratio. Measured data sets p(t) are separately saved in intervals of 5−20 min with a specific ΔB tag for each data set.

To correct for frequency drift, we multiply each data set p(t) by e −iΔωt, where Δω = γ nΔB is the expected shift in the 13C nuclear resonance due to the drift in magnetic field. γ n = 2π × 10.7 MHz/T is the 13C gyromagnetic ratio and T is the maximum t time. The corrected data sets p(t) are then Fourier transformed and averaged. Alternatively, the averaged NMR spectrum can also be obtained by performing a Fourier transform of the uncorrected p(t) and shifting the frequency scale for each spectrum before averaging.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Schirhagl, R., Chang, K., Loretz, M. & Degen, C. L. Nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond: nanoscale sensors for physics and biology. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 65, 83 (2014).

Rondin, L. et al. Magnetometry with nitrogen-vacancy defects in diamond. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77, 056503 (2014).

Degen, C. L. Scanning magnetic field microscope with a diamond single-spin sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 243111 (2008).

Balasubramanian, G. et al. Nanoscale imaging magnetometry with diamond spins under ambient conditions. Nature 455, 648 (2008).

Rondin, L. et al. Nanoscale magnetic field mapping with a single spin scanning probe magnetometer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 153118 (2012).

Maletinsky, P. et al. A robust scanning diamond sensor for nanoscale imaging with single nitrogen-vacancy centres. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 320–324 (2012).

Dussaux, A. et al. Local dynamics of topological magnetic defects in the itinerant helimagnet fege. Nat. Commun. 7, 12430 (2016).

Kolkowitz, S. et al. Probing johnson noise and ballistic transport in normal metals with a single-spin qubit. Science 347, 1129 (2015).

Ajoy, A., Bissbort, U., Lukin, M. D., Walsworth, R. L. & Cappellaro, P. Atomic-scale nuclear spin imaging using quantum-assisted sensors in diamond. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011001 (2015).

Lazariev, A. & Balasubramanian, G. A nitrogen-vacancy spin based molecular structure microscope using multiplexed projection reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 5, 14130 (2015).

Kost, M., Cai, J. & Plenio, M. B. Resolving single molecule structures with nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Sci. Rep. 5, 11007 (2015).

Cywinski, L., Lutchyn, R. M., Nave, C. P. & Sarma, S. D. How to enhance dephasing time in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. B 77, 174509 (2008).

Alvarez, G. A. & Suter, D. Measuring the spectrum of colored noise by dynamical decoupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 230501 (2011).

Lange, G. D., Riste, D., Dobrovitski, V. V. & Hanson, R. Single-spin magnetometry with multipulse sensing sequences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 080802 (2011).

Kotler, S., Akerman, N., Glickman, Y., Keselman, A. & Ozeri, R. Single-ion quantum lock-in amplifier. Nature 473, 61–65 (2011).

Loretz, M. et al. Spurious harmonic response of multipulse quantum sensing sequences. Phys. Rev. X 5, 21009 (2015).

Loretz, M., Pezzagna, S., Meijer, J. & Degen, C. L. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a 1.9-nm-deep nitrogen-vacancy sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 33102 (2014).

Laraoui, A., Hodges, J. S., Ryan, C. A. & Meriles, C. A. Diamond nitrogen-vacancy center as a probe of random fluctuations in a nuclear spin ensemble. Phys. Rev. B 84, 104301 (2011).

Laraoui, A. et al. High-resolution correlation spectroscopy of c-13 spins near a nitrogen-vacancy centre in diamond. Nat. Commun. 4, 1651 (2013).

Staudacher, T. et al. Probing molecular dynamics at the nanoscale via an individual paramagnetic centre. Nat. Commun. 6, 8527 (2015).

Kong, X., Stark, A., Du, J., McGuinness, L. P. & Jelezko, F. Towards chemical structure resolution with nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 024004 (2015).

Boss, J. M. et al. One- and two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with a diamond quantum sensor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 197601 (2016).

Jiang, L. et al. Repetitive readout of a single electronic spin via quantum logic with nuclear spin ancillae. Science 326, 267–272 (2009).

Lovchinsky, I. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance detection and spectroscopy of single proteins using quantum logic. Science 351, 836 (2016).

Schmidt, P. O. et al. Spectroscopy using quantum logic. Science 309, 749–752 (2005).

Hume, D. B., Rosenband, T. & Wineland, D. J. High-fidelity adaptive qubit detection through repetitive quantum nondemolition measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 120502 (2007).

Rosenband, T. et al. Frequency ratio of al+ and hg+ single-ion optical clocks; metrology at the 17th decimal place. Science 319, 1808–1812 (2008).

Lloyd, S. & Viola, L. Engineering quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 65, 010101 (2001).

Barreiro, J. T. et al. An open-system quantum simulator with trapped ions. Nature 470, 486–491 (2011).

Szankowski, P., Trippenbach, M. & Cywinski, L. Spectroscopy of cross correlations of environmental noises with two qubits. Phys. Rev. A 94, 012109 (2016).

Paz-Silva, G. A., Norris, L. M. & Viola, L. Multiqubit spectroscopy of gaussian quantum noise. Phys. Rev. A 95, 022121 (2017).

Unden, T. et al. Quantum metrology enhanced by repetitive quantum error correction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 230502 (2016).

Ticozzi, F. & Viola, L. Single-bit feedback and quantum-dynamical decoupling. Phys. Rev. A 74, 052328 (2006).

Hirose, M. & Cappellaro, P. Coherent feedback control of a single qubit in diamond. Nature 532, 77 (2016).

Zaiser, S. et al. Enhancing quantum sensing sensitivity by a quantum memory. Nat. Commun. 7, 12279 (2016).

Neumann, P. et al. Single-shot readout of a single nuclear spin. Science 329, 542–544 (2010).

Aslam, N., Waldherr, G., Neumann, P., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Photo-induced ionization dynamics of the nitrogen vacancy defect in diamond investigated by single-shot charge state detection. New. J. Phys. 15, 013064 (2013).

Pfender, M. et al. Nonvolatile quantum memory enables sensor unlimited nanoscale spectroscopy of finite quantum systems. arXiv:1610.05675. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.05675 (2016).

Mamin, H. J. et al. Nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance with a nitrogen-vacancy spin sensor. Science 339, 557–560 (2013).

Staudacher, T. et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy on a (5-nanometer)(3) sample. Science 339, 561–563 (2013).

Mamin, H. et al. Multipulse double-quantum magnetometry with near-surface nitrogen-vacancy centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 030803 (2014).

Wang, Z. Y., Casanova, J. & Plenio, M. B. Delayed entanglement echo for individual control of a large number of nuclear spins. Nat. Commun. 8, 14660 (2017).

Ma, W. & Liu, R. Proposal for quantum sensing based on two-dimensional dynamical decoupling: NMR correlation spectroscopy of single molecules. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 054012 (2016).

Shi, F. et al. Sensing and atomic-scale structure analysis of single nuclear-spin clusters in diamond. Nat. Phys. 10, 21–25 (2014).

Holland, D. J., Bostock, M. J., Gladden, L. F. & Nietlispach, D. Fast multidimensional NMR spectroscopy using compressed sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6548–6551 (2011).

Momenzadeh, S. A. et al. Nanoengineered diamond waveguide as a robust bright platform for nanomagnetometry using shallow nitrogen vacancy centers. Nano. Lett. 15, 165–169 (2015).

Matsuzaki, Y. et al. Hybrid quantum magnetic-field sensor with an electron spin and a nuclear spin in diamond. Phys. Rev. A 94, 052330 (2016).

Chen, M., Hirose, M. & Cappellaro, P. Measurement of transverse hyperfine interaction by forbidden transitions. Phys. Rev. B 92, 020101 (2015).

Kotler, S., Akerman, N., Glickman, Y. & Ozeri, R. Nonlinear single-spin spectrum analyzer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 110503 (2013).

Rosskopf, T. et al. Investigation of surface magnetic noise by shallow spins in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 147602 (2014).

Degen, C. L., Reinhard, F. & Cappellaro, P. Quantum sensing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 035002 (2017).

Gullion, T., Baker, D. B. & Conradi, M. S. New, compensated carr-purcell sequences. J. Magn. Res 89, 479–484 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We thank Kristian Cujia, Jan Meijer, Sebastien Pezzagna, Nicole Raatz, and Lorenza Viola for insightful comments and for help with sample preparation. This work was supported by Swiss NSF Project Grant 200021_137520, the NCCR QSIT, and the DIADEMS programme 611143 of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.D. conceived the project. T.R. set up the experiment, carried out the measurements, and performed the analysis with help from J.Z., J.M.B., and C.L.D. T.R., and C.L.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosskopf, T., Zopes, J., Boss, J.M. et al. A quantum spectrum analyzer enhanced by a nuclear spin memory. npj Quantum Inf 3, 33 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0030-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-017-0030-6

This article is cited by

-

Optical-domain spectral super-resolution via a quantum-memory-based time-frequency processor

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Heterodyne sensing of microwaves with a quantum sensor

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Nuclear spin assisted magnetic field angle sensing

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Algorithmic decomposition for efficient multiple nuclear spin detection in diamond

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Hyperpolarized relaxometry based nuclear T1 noise spectroscopy in diamond

Nature Communications (2019)