Abstract

Supported self-management reduces asthma-related morbidity and mortality. This paper is on a feasibility study, and observing the change in clinical and cost outcomes of pictorial action plan use is part of assessing feasibility as it will help us decide on outcome measures for a fully powered RCT. We conducted a pre–post feasibility study among adults with physician-diagnosed asthma on inhaled corticosteroids at a public primary-care clinic in Malaysia. We adapted an existing pictorial asthma action plan. The primary outcome was asthma control, assessed at 1, 3 and 6 months. Secondary outcomes included reliever use, controller medication adherence, asthma exacerbations, emergency visits, hospitalisations, days lost from work/daily activities and action plan use. We estimated potential cost savings on asthma-related care following plan use. About 84% (n = 59/70) completed the 6-months follow-up. The proportion achieving good asthma control increased from 18 (30.4%) at baseline to 38 (64.4%) at 6-month follow-up. The proportion of at least one acute exacerbation (3 months: % difference −19.7; 95% CI −34.7 to −3.1; 6 months: % difference −20.3; 95% CI −5.8 to −3.2), one or more emergency visit (1 month: % difference −28.6; 95% CI −41.2 to −15.5; 3 months: % difference −18.0; 95% CI −32.2 to −3.0; 6 months: % difference −20.3; 95% CI −34.9 to −4.6), and one or more asthma admission (1 month: % difference −14.3; 95% CI −25.2 to −5.3; 6 months: % difference −11.9; 95% CI −23.2 to −1.8) improved over time. Estimated savings for the 59 patients at 6-months follow-up and for each patient over the 6 months were RM 15,866.22 (USD3755.36) and RM268.92 (USD63.65), respectively. Supported self-management with a pictorial asthma action plan was associated with an improvement in asthma control and potential cost savings in Malaysian primary-care patients.

Trial registration number: ISRCTN87128530; prospectively registered: September 5, 2019, http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN87128530.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma affects almost 300 million people globally and 100 million people in Southeast Asia1,2. Most asthma-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries2. Annually in Malaysia, 68% of people with asthma visit their doctor; 50% attend emergency department, and 10% are admitted, this representing substantial morbidity and incurring substantial emergency healthcare costs3,4. Only a third of people with asthma attend regular follow-up care with low usage of controller medications and overuse of oral short-acting beta-agonist5,6,7. Despite this, asthma is not a healthcare priority in Malaysia compared to other non-communicable diseases (cardiovascular diseases and diabetes) and is relatively underfunded8.

All major national and international asthma guidelines recommend asthma self-management that is personalised to patients’ preferences and views9,10 to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare costs11,12. Asthma action plans are an integral component of supported self-management in which patients are given written advice on how to adjust their treatment according to changes in their disease status9,10,13. However, in Malaysia, about 60% of adults with asthma have limited health literacy challenging use of traditional text-based plan14. An action plan that provides guidance in a pictorial format has the potential to overcome inequities15,16,17,18 for people with limited literacy and numeracy skills by making complex health information easier to comprehend19, and beneficial20.

Several studies have reported pictorial asthma action plan for use in adults20,21,22. Roberts et al. have developed a validated pictorial asthma action plan that was comprehensible in three different populations of asthma patients, including Malaysia20. Two controlled trials using validated pictorial action plans have yielded contrasting findings21,22. A non-randomised controlled trial among ‘illiterate’ women with asthma in Turkey showed that pictorial action plans improved asthma control and quality of life21 whilst a randomised controlled trial (n = 62) in a semi-urban primary-care clinic in Malaysia found no significant difference in asthma control between patients who received a pictorial or text-based action plan22. In the Malaysian study, the participants had relatively well-controlled asthma at baseline, potentially reducing the scope for improvement. In addition, the pictorial plan used in the study did not align with the advice of the Malaysian asthma guideline.

A previous study on delivering supported self-management in the context of Malaysian primary care highlighted that the written action plan endorsed by the Malaysian Thoracic Society10 was not understood by patients possibly because of limited health literacy combined with the language challenges of living in a multilingual society23. We have explored this issue in some detail24 and found that a written action plan is a particularly an important barrier in Malaysia, hence, the need to explore the role of a pictorial action plan in asthma-supported self-management.

We therefore aimed to determine the feasibility of providing a pictorial action plan for adult patients with asthma and estimate its potential impact on asthma control, medication use, healthcare utilisation, costs and days lost from work or usual activities as well as the feasibility of assessing costs related to asthma care. Our findings will inform the design of a future randomised controlled trial.

Methods

Study design and setting

Embedded within the Medical Research Council framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions25, this pre–post feasibility study was conducted in an urban public primary-care clinic in the district of Klang, Selangor, Malaysia between September 2019 to July 2020. The study protocol was registered with BMC ISRCTN Registry [ISRCTN87128530; prospectively registered: September 5, 2019, http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN87128530]. The state of Selangor was chosen as it has a high prevalence of adults with asthma (22%), especially in urban communities as well as the highest prevalence of limited health literacy in Malaysia at 75%26.

Participants

The study participants were recruited from one of the primary-care clinics under the Klang Asthma Cohort (KAC) registry (a clinical asthma patients registry) using an Excel-generated simple random table by a research member, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1. Klang Asthma Cohort is a cohort of 1280 people with asthma recruited from six primary-care clinics in Klang who are willing to be approached for future research. A detailed description of KAC can be accessed at https://www.ed.ac.uk/usher/respire/chronic-respiratory-disorders/asthma-care.

Participants were contacted via a telephone call (to avoid written communication in people with limited literacy) by a trained research assistant who provided a detailed description of the study. Those who agreed to participate in the study met face-to-face with the research assistant at the clinic to provide written informed consent and to answer the baseline questionnaire.

As this was a feasibility study, a formal sample size calculation was not required. Seventy participants were recruited, which was deemed to be adequate to inform the feasibility of delivering the intervention27.

Usual clinic care and self-management support

The selected primary-care clinic has a dedicated asthma clinic that operates one afternoon a week involving medical officers, pharmacists and nurses. Medical officers are doctors without postgraduate training who work in primary-care clinics under the leadership of specialist family physicians. They are trained to assess asthma control, check the use of peak expiratory flow rate, recommend appropriate treatment, and deliver supported self-management including a text-based asthma action plan, and as the participants’ usual doctor, continued to provide care throughout this study. The pharmacists taught inhaler technique and discussed adherence to medications and asthma action plans. The nurses provided asthma education. For participants in this feasibility study, the clinic management continued as usual, but a pictorial asthma action plan was provided instead of the standard text-based action plan.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of a pictorial asthma action plan (see Supplementary Fig. 1) instead of the text-based action plan incorporated within the existing self-management education and support, and is described in Table 2 using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist28.

Outcome measures

All study outcomes were measured at baseline and at 1-, 3- and 6 months post intervention as in the questionnaire (see Supplementary Information: Questionnaire). We initially intended to follow up the participants over 12 months but had to stop data collection at 6 months to comply with restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Asthma control was the primary outcome and measured using the validated Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Asthma Symptoms Control9. This questionnaire comprises four questions that measure the adequacy of asthma treatment in the past four weeks. The questions focus on the day and night-time symptoms, use of reliever, and limitation of activity due to asthma. The option for each response is either 'Yes' or 'No'. Well-controlled was considered if the responses to all questions were 'No'. Any responses of 'Yes' were considered as not controlled.

The secondary outcomes measured in this study all related to the previous 1 month:

-

Number of times reliever medication (inhaled or oral bronchodilators) was used

-

Adherence to controller medication

-

Frequency of acute exacerbations (defined as episodes characterised by acute or subacute onset of progressively worsening symptoms, such as shortness of breath, cough, wheezing or chest tightness, which are worse than the patient's usual status and require a change in treatment)

-

Frequency of asthma-related emergency visits (to a health clinic and/or hospital emergency department)

-

Frequency of asthma-related admissions

-

Numbers of days lost from work for asthma treatment (defined as the number of days of medical leave taken by an employee, or unable to work if self-employed)

-

Number of times the participants reported using their pictorial asthma action plan in the previous month.

Data collection

Data were collected face-to-face using a pretested structured questionnaire in English or Malay language. At baseline, there were four sections to the questionnaire:

Section 1: Socio-demographic and socio-economic information, including age, gender, ethnicity, highest education level, occupation, marital status, personal and household incomes.

Section 2: Medical and healthcare information, including duration of asthma, triggers and allergies, frequency of attacks, use of healthcare resources, medications, vaccinations, current and history of alternative treatment use, smoking status, co-morbid conditions, previous asthma education and ownership/use of an asthma action plan, use of an asthma diary.

Section 3: Asthma control assessment using the GINA Asthma Symptom Control.

Section 4: Health literacy was measured using the validated 47-item Asian version of the Health Literacy Survey-Asia-Q47 (HLS-ASIA-Q47) which assesses the ability to access, understand, appraise, and use health information in the context of healthcare, disease prevention, and health promotion29. The HLS-Asia-Q47 has been shown to be valid and reliable for use in Malaysia30. It was rated on 4-Likert scale, ranged from 1 = very difficult to 4 = very easy. According to the instructions with the HLS-ASIA-Q47, an index of health literacy score was constructed using the mean-based scores of the 47 items. These were transformed into a unified metric ranging from 0 to 50 using the formula = (mean – 1)* (50/3)31. The index scores were grouped into two categories: limited and adequate health literacy. An index score of ≤33 indicates limited health literacy31.

Information on healthcare visits (emergency visits at the clinic for attacks) were verified by clinic doctors from the participants’ medical records. In case of any discrepancies, the information was checked with the patients, as patients in Malaysia might seek care from other health providers, and the medical record may not be complete.

Follow-up data on all the primary and secondary outcomes were collected at 1-, 3- and 6-month post intervention by trained enumerators who were medical doctors not involved in patients’ recruitment and baseline assessments. At every follow-up visit, primary and secondary outcomes were collected, and participants asked about reasons for using a pictorial action plan and any barriers and facilitators.

Data analysis

We used IBM SPSS version 26.032 and R software version 4.0.433,34,35, for the statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis of the baseline variables was reported using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical data. Chi-squared or Fisher’s Exact tests (for small numbers) for categorical variables and independent samples t test for continuous data were used to compare the difference in baseline characteristics between the participants who had completed, withdrawn or lost to follow-up.

The primary and secondary outcomes were categorised as binary data. We calculated the difference in paired percentages with well-controlled asthma, no reliever use, at least one missed day using controller medication, at least one acute exacerbation, at least one emergency visit, and at least one admission, for each of the follow-up time points compared to baseline. The analysis was completed using all data available with no imputation made for missing data (i.e., missing data were left as missing). The 'modified Wilson score method' or 'Newcombe score method' was used to calculate the Exact 95% confidence intervals for all paired differences.

Feasibility of assessing the cost of asthma-related care

An expert panel comprising a Ministry of Health (MoH) family medicine specialist and a pharmacist, and the research team who were family medicine specialists and a respiratory physician, reached consensus on the annual cost of care for a person with well-controlled and uncontrolled asthma. The unit costs of specialist and general outpatient visits were obtained from the legislated fee schedules for the Ministry of Health, Malaysia services which reflect the actual cost of services36. The fee schedule details fees for MoH facilities for non-citizens who were not eligible for subsidised healthcare in Malaysia. Thus, the fees are the estimated cost of care in public health facilities in the country. We estimated the cost savings over six months for the participants who completed the study. This estimation was based on the differences between the estimated cost incurred in the absence of the intervention and the actual costs as observed. However, resource use had only been captured for 3 months out of the 6-months follow-up (for months 1, 3 and 6 during the follow-up at 1 month, 3 months and 6 months). Therefore, in order to estimate medication costs, it was assumed that (a) asthma status at baseline remained throughout month 1; (b) asthma status at 1-month follow-up remained for months 2 and 3; and (c) asthma status at the 3-month follow-up remained for months 4, 5 and 6. The details are discussed in the Supplementary Information: Cost of asthma-related care and Supplementary Table 1.

Ethics approval

Regulatory approvals have been obtained in line with the operating procedures of the RESPIRE Global Unit, including approvals from the National Medical Research Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Malaysia [NMRR-18-2683-43494] and relevant authorities involved in the Klang District. Both verbal and written informed consent were obtained from eligible participants before the involvement of this study. Confidentiality of the participants was ensured; data were anonymised before publication or report writing. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the International Conference on Harmonisation Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. This study also received sponsorship approval from the Academic and Clinical Central Office for Research & Development (ACCORD) at the University of Edinburgh.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

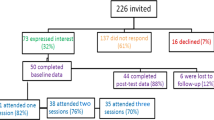

Figure 1 summarises the flow of the participants in the study. We identified and screened 120 adult patients with asthma from the KAC registry for eligibility between June and August 2019. Of these, 72 eligible participants were recruited, two withdrew immediately after recruitment for personal reasons, therefore, 70 participants were enrolled in this study and attended the baseline clinic visits between September and November 2019. Of the 70 participants, 59 (84.3%) completed a 6-month follow-up. Table 3 compares the participants who completed the study and those who lost to follow-up. Those who lost to follow-up had higher personal income than those who completed the study (P = 0.019).

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the participants was 51.2 ± SD15.5 years, 58.6% were women, 72.3% were married and 48.6% were Indian, 42.9% were Malay and 8.6% with Chinese and other ethnicities. The majority (91.4%) of the participants had previously received supported self-management asthma education from the clinic staff, 25 (35.7%) had a written action plan of whom only 60% had used the plan. Even though 54 (77.1%) had an asthma diary, only 14 of them used it. About one-fifth of the participants used complementary and alternative medicines. In terms of health literacy, 61.4% had limited literacy. Only 24.3% used a smartphone for asthma information.

Asthma control

There was an increasing proportion of well-controlled asthma from baseline to 6-month follow-up. In addition, there was an improvement in the proportion of controlled asthma at three months (% difference = 26.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 9.3, 41.1) and at 6 months (% difference = 33.9; 95% CI = 18.6, 46.7) post intervention compared to baseline as shown in Table 4.

Secondary outcomes

As shown in Table 5, the proportion of those with at least one acute exacerbation in the previous month reduced by 20% at the 3-month and 6-month follow-up compared to baseline. Further, the proportion of at least one emergency visit in the previous month reduced by 18% and 20% at the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups. Similarly, the proportion who had been hospitalised in the previous month reduced by 12% in the month prior to the 6-month follow-up compared to baseline.

At baseline, 12 out of the 70 patients reported at least one day of work loss in the previous 1 month due to asthma (results not shown in table). However, during the study period follow-ups, only 1 patient reported at least one day of work loss at 6-month follow-up.

The proportion that had used the pictorial asthma action plan in the previous month was 58.7% (n = 37), 39.3% (n = 24) and 33.9% (n = 20) at 1, 3 and 6-month follow-ups compared to 21.4% (n = 15) who used the written action plan at baseline. The motivations for use included having better asthma control, ease of use and feeling better after using the action plan. Reasons for not using the action plan included 'knowing the action plan by heart', feeling well, and forgetting that they had one.

Fidelity to delivering the intervention

The fidelity check showed that all participants were recorded as having received counselling on supported self-management and were given the personalised pictorial asthma action plan with relevant medication information by the attending medical officer. All had recorded being given teaching on inhaler technique and medication adherence from the attending pharmacist.

Cost savings from the use of action plan

The cost-saving analysis was focused on the 59 patients who were available at 6-month follow-up. The estimation of cost saving was based on the differences between the estimated cost incurred in the absence of the intervention and the actual costs as observed. The estimations of the cost incurred in the absence of the intervention (using the action plan) and the actual costs as observed over the 6 months are summarised in Supplementary Information: Cost savings from use of action plan and in Supplementary Tables 2–6). The estimated cost savings from using the action plan for the entire cohort at 6-months follow-up was RM 15,866.22 USD3755.36), and for each patient over the 6 months was 1 RM268.92 (USD63.65), (RM1.00 = USD4.22 on June 6, 2022). Further details on the cost estimated for cost savings from the use of the action plan are described in the Supplementary Information: Cost savings from the use of the action plan.

Discussion

The pictorial asthma action plan was feasible for use in the Malaysian primary-care setting and has the potential to show clinically significant effects in future studies. With the use of the pictorial asthma action plan, our study has shown an improvement in asthma control at 3- and 6-month follow-ups, and a reduction in acute exacerbations and emergency visits at 3- and 6-months follow-ups, as well as a reduction in hospital admissions at 6-months follow-up. If confirmed in a randomised controlled trial, these improvements have the potential to reduce healthcare costs.

In our study, the doctors, pharmacists and nurses worked together in providing asthma-supported self-management. This is in line with the Malaysian primary healthcare delivery where the goal is to provide comprehensive care by a team comprising doctors, pharmacists, assistant medical officers, and nurses as well as other allied healthcare professionals37. To prepare for this, we conducted a 2-h group training session for the doctors and pharmacists on the correct use of the pictorial action plan. We also involved the nurses to make them aware about the use of the action plan in clinical practice. The training included role-plays that incorporated communication skills training with simulated patients, as patient-centred communication has been shown to increase the self-efficacy of the healthcare professionals in delivering counselling38.

The recruitment of study participants was facilitated by recruiting participants from the Klang Asthma Cohort registry and enrolment occurred on their follow-up appointment dates for their asthma care at the clinic. The use of a registry enabled timely recruitment and allowed the identification of potential study participants based on eligibility criteria39. In addition, enrolment conducted during their scheduled clinic visits facilitated participation with a retention rate of more than 80% at 6-month follow-up. On the other hand, patients who are engaged in the clinical registry may not be typical of people with asthma. They have better commitment towards their healthcare, which will have contributed to the relatively high retention rate observed in our study40. In our study, those lost to follow-up were significantly younger and had higher personal income, suggesting that they were more likely to be working or have busy jobs. Uptake of the pictorial asthma action plan and retention in future studies may therefore be improved by offering asthma care during weekends and at private healthcare facilities. From a practical perspective, primary-care clinics could develop their own chronic respiratory disease registry to facilitate identification of patients with limited health literacy to enhance their healthcare.

Asthma control in the present study improved over the 6 months of the study. Similarly, a non-randomised controlled study among women with poor literacy skills who received a pictorial asthma action plan in Turkey showed improvement in asthma control over 6-month duration. In addition, they also found a significant difference at first and second month follow-up when compared to patients who received usual asthma care21. However, despite a trend to improvement at 3 months, a trial in Malaysia conducted among patients who attended a semi-urban primary-care clinic did not show a significant difference in asthma control between those who were provided with the action plan and those who received usual care22. This could be because their trial had high proportion of patient with good asthma control at baseline.

Our study showed a reduction in the proportion of asthma adults with acute events over the 6 months of the study. This is similar to the findings of ref. 21 and reflects the known benefits of optimal self-management that includes education, action plan and regular review and reflects the known benefits of optimal self-management that includes education, action plan and regular review11,12. However, as in any before-and-after study, we cannot rule out other factors which may have confounded the intervention effect estimates. Our study was partially conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when social distancing and face masks reduced exposure to asthma triggers such as viral infections, environmental pollution and dust. A reduction in acute attacks during the pandemic has been described in the UK41,42. In addition, the requirement to ‘work from home’ during the pandemic may have been responsible for the reduced need for medical leave that we observed.

Similar to our findings, optimal asthma control has been associated with reduced total healthcare costs in a longitudinal study conducted among adults with asthma in two primary-care clinics in Singapore43. Therefore, any approach incorporated into supported self-management for asthma (such as a pictorial action plan) could not only potentially improve asthma control but also achieve total cost savings for the healthcare system. Our findings were encouraging, but a formal health economic evaluation should be included in a future trial.

This study evaluated the feasibility of a potentially important intervention to improve asthma control among adults with asthma in low- and middle-income countries. We followed a recognised process for content validation of the adapted pictorial asthma action plan, which assessed elements of ‘guessability and translucency’ though not using the methodology employed in the original validation study of the pictorial action plans20. Training the healthcare professionals to deliver self-management supported by a pictorial action plan is feasible and may have facilitated better asthma control.

However, there are some limitations. First, a lack of a concurrent control group limits the interpretation to an association and evidence of effectiveness, hence, the need for a randomised controlled trial. Second, we recruited participants via the Klang Asthma Cohort but practices that collaborate with quality improvement research, and their patients who consent to be on a research registry may not be typical of Malaysian primary care and people with asthma. Third, we did not used limited health literacy as an inclusion criterion so we are not able to assess the impact of pictorial plan specifically among those with limited health literacy. However, we are seeking to develop an intervention which can be implemented in routine clinical practice, and formally assessing health literacy prior to providing an action plan is not likely to be normal practice. In the context of high levels of limited health literacy (60%), assuming that a pictorial plan will be most appropriate is likely to be the ‘safest’ option.

The plan does not include the ‘amber’ step of increasing inhaled steroids included in commonly used action plans and does not provide advice for people using combination inhalers. Whilst this may be a limitation, it aligns with the national guideline10, which may have enhanced implementation. In addition, whilst emergency steroids are rarely prescribed, advice on when oral steroids are required could prompt timely seeking of medical advice. Future iterations of the action plan will reflect changes in national policy (e.g., use of combination ICS/formoterol as both the reliever and controller as recommended in the current global guidelines44). This study will allow informed planning for a future definitive randomised controlled trial.

Fourth, we were not able to verify some secondary outcomes as these were self-reported, hence these results were subjected to recall bias. Next, we found asthma control improved following the used of the action plan, a possible confounder could relate to the COVID-19 pandemic, when social distancing restrictions would have limited exposure to asthma triggers such as circulating viruses, dust or pollens which may have contributed to the improved asthma control observed. In contrast, during the pandemic, the participants’ follow-up and care may be atypical (potentially access was reduced during periods of lockdown), hence, future studies need to consider remote access to healthcare providers. Further, our study was not designed to identify which aspect(s) of asthma self-management are critical to changing behaviour. Finally, because COVID related delays and restrictions, the study duration was limited to 6 months rather than the planned 12 months which may have introduced seasonal biases and also prevented observation of long-term sustainability.

A pictorial asthma action plan for adult asthma patients has the potential to contribute to improving asthma control in the context of Malaysian primary care. This study provides evidence of the feasibility of training primary healthcare professionals and the use of pictorial action plans, suggesting that the intervention has the potential to proceed to a full trial. Furthermore, the pictorial action plan was associated with a favourable impact on asthma control. Future work may include the development of a technology-based intervention for adult asthma patients and a pilot randomised controlled trial, to further improve access.

Data availability

The dataset of this study will be held in the Edinburgh DataVault, accessible only to authorised University of Edinburgh staff. Access to the data will be from the Depositor, or in their absence the Contact Person or Data Manager. Further information on retrieving data from the DataVault can be found at http://www.ed.ac.uk/information- services/research-support/research-data-service/sharing-preserving-data/datavault/interim-datavault/retrieve-data. Associated publicly available files will be published at https://datashare.ed.ac.uk/handle/10283/4226/restricted-resource?bitstreamId=727d24b8-7643-4d61-b21e-b8dfccd46bd2.

Code availability

The codes generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Mathers, C. D., Boerma, T., Ma & Fat, D. Global and regional causes of death. Br. Med. Bull. 92, 7–32 (2009).

To, T. et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 12, 204–210 (2012).

Institute for Public Health. The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey (NMHS III) 2006, Asthma. Ministry of Health, Malaysia (IPH, 2008).

Yong, Y. V. & Shafie, A. A. How much does management of an asthma-related event cost in a Malaysian suburban hospital? Value Health Reg. Issues 15, 6–11 (2018).

Lee, P. Y. & Khoo, E. M. How well were asthmatic patients educated about their asthma? A study at the emergency department. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 16, 45–49 (2004).

Zainudin, B. M. Z., Kai Wei Lai, C., Soriano, J. B., Jia-Horng, W. & De Guia, T. S. Asthma insights and reality in Asia-Pacific (AIRIAP) Steering Committee. Asthma control in adults in Asia-Pacific. Respirology 10, 579–586 (2005).

Chin, M. C., Sivasampu, S. & Khoo, E. M. Prescription of oral short-acting beta 2-agonist for asthma in non-resource poor settings: a national study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 12, e0180443–12 (2017).

Department of Public Health. National Strategic Plan for Non-Communicable Disease: Medium Term Strategic Plan to Further Strengthen the NCD Prevention and Control Program in Malaysia (2016–2025). (Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2016).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2019 Update). Global Initiative for Asthma - GINA https://ginasthma.org/ (2019).

Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS). Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Asthma in Adults (Medical Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017).

Pinnock, H. et al. Systematic meta-review of supported self-management for asthma: a healthcare perspective. BMC Med. 15, 64–95 (2017).

Gibson, P. G. et al. Self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001117 (2002).

Ignacio-García, J. M. et al. Benefits at 3 yrs of an asthma education programme coupled with regular reinforcement. Eur. Respir. J. 20, 1095–1101 (2002).

Salim, H. et al. Health literacy levels and its determinants among people with asthma in Malaysian primary healthcare settings: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1186–1195 (2021).

Houts, P. S., Doak, C. C., Doak, L. G. & Loscalzo, M. J. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 61, 173–190 (2006).

Burbank, A. J. et al. Mobile-based asthma action plans for adolescents. J. Asthma 52, 583–586 (2015).

Barros, I. M. C. et al. The use of pictograms in the health care: a literature review. Res Soc. Adm. Pharm. 10, 704–719 (2014).

Mitchell, S. J., Bilderback, A. L. & Okelo, S. O. Feasibility of picture-based asthma medication plans in urban pediatric outpatient clinics. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 29, 95–99 (2016).

Visual Communication Resources | Health Literacy | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/developmaterials/visual-communication.html (2019).

Roberts, N. J. et al. The development and comprehensibility of a pictorial asthma action plan. Patient Educ. Couns. 74, 12–18 (2009).

Ozyigit, L. P., Ozcelik, B., Ciloglu, S. O. & Erkan, F. The effectiveness of a pictorial asthma action plan for improving asthma control and the quality of life in illiterate women. J. Asthma 51, 423–428 (2014).

Radzniwan, M. R., Chow, S. Y., Shamsul, A. S. & Ali, M. F. Effectiveness of pictorial based self-management among adult with asthma in a suburban primary care health clinic: a randomised controlled trial. Brunei Int. Med. J. 12, 183–190 (2016).

Salim, H. et al. Insights into how Malaysian adults with limited health literacy self-manage and live with asthma: a photovoice qualitative study. Health Expect. 25, 163–176 (2022).

Lee, P. Y. et al. Barriers to implementing asthma self-management in Malaysian primary care: qualitative study exploring the perspectives of healthcare professionals. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 31, 1–8 (2021).

Craig, P. et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions. https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/ (2019).

Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: Non-communicable Diseases, Healthcare Demand, and Health Literacy—Key Findings. (National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2020).

Teare, M. D. et al. Sample size requirements to estimate key design parameters from external pilot randomised controlled trials: a simulation study. Trials 15, 264–276 (2014).

Hoffmann, T. C. et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348, g1687–g1699 (2014).

Sørensen, K. et al. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 13, 948–958 (2013).

Duong, T. V. et al. Measuring health literacy in Asia: validation of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey tool in six Asian countries. J. Epidemiol. 27, 80–86 (2016).

Sørensen, K. et al. Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 25, 1053–1058 (2015).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, Version 26.0. (IBM Corp., 2019).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2021).

Newcombe, R. G. Improved confidence intervals for the difference between binomial proportions based on paired data. Stat. Med. 17, 2635–2650 (1998).

Newcombe, R. G. & Altman, D. G. Proportions and their differences. in Statistics with Confidence: Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines (eds. Altman, D. G. et al.) 45–56 (BMJ Books, 2000).

Ng CW. Case study of Malaysia. in Price Setting and Price Regulation in Health Care: Lessons for advancing Universal Health Coverage. World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (WHO, 2019).

Noh, D. K. M. Primary health care reform in 1CARE for 1 Malaysia. Intern J. Public Health Res Spec. 2011, 50–56 (2011).

Nørgaard, B., Ammentorp, J., Kyvik, K. O. & Kofoed, P. E. Communication skills training increases self-efficacy of health care professionals. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 32, 90–97 (2012).

Tan, M. H., Thomas, M. & MacEachern, M. P. Using registries to recruit subjects for clinical trials. Contemp. Clin. Trials 41, 31–38 (2015).

Solomon, D. H. et al. Clinical patient registry recruitment and retention: a survey of patients in two chronic disease registries. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 17, 59–65 (2017).

Shah, S. A., Quint, J. K., Nwaru, B. I. & Sheikh, A. Impact of COVID-19 national lockdown on asthma exacerbations: interrupted time-series analysis of English primary care data. Thorax 76, 860–866 (2021).

Davies, G. A. et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on emergency asthma admissions and deaths: national interrupted time series analyses for Scotland and Wales. Thorax 76, 867–873 (2021).

Nguyen, H. V. et al. Association between asthma control and asthma cost: results from a longitudinal study in a primary care setting. Respirology 22, 454–459 (2017).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (2022 Update). Global Initiative for Asthma - GINA https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ (2022).

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 6, 42–53 (2011).

Lawshe, C. H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 28, 563–575 (1975).

Acknowledgements

The RESPIRE collaboration comprises the UK Grant holders, Partners and research teams as listed on the RESPIRE website (www.ed.ac.uk/usher/respire), including Aziz Sheikh. The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for the permission to publish this paper. Patients and public are involved in the over-arching programme of work developing and evaluating interventions to improve asthma care. They reviewed the protocol and all patient-related materials (including questionnaires, participant information sheets and consent forms) to assess appropriate terminology. In addition, they advised on the design of the pictorial action plan. We also thank all RESPIRE investigators from Klang District for their contribution to useful discussions on this research project. Also, thank you to Nur Sabrina Abd Rasip, Roshan Nur Anand Ananthan and Jasmine Wong for their assistance in this project. This research was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE); 16/136/109) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

S.G.S., P.Y.L., A.T.C., H.S., E.M.K., H.P. and S.M.L. conceptualised the study. All authors contributed to the design and content of the intervention. C.W.N. and A.S. contributed to the cost-savings content. R.P. contributed to the content of data analysis and sample size estimation. S.G.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript; and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no conflict of interest except for E.M.K. E.M.K. reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research Global Health Research Unit on Respiratory Health (RESPIRE) and Seqirus UK; personal fees from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; and is a board director of the International Primary Care Respiratory Group. H.P. and E.M.K. are editors for npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine. H.P. and E.M.K. were not involved in the journal’s review of, or decisions related to, this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sazlina, S.G., Lee, P.Y., Cheong, A.T. et al. Feasibility of supported self-management with a pictorial action plan to improve asthma control. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 32, 34 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00294-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-022-00294-8