Abstract

Primary Care Providers (PCPs) often deal with patients on daily clinical practice without knowing anything about their smoking status and willingness to quit. The aim of this metasynthesis is to explore the PCPs and patients who are smokers perspectives regarding the issue of smoking cessation within primary care settings. It relies on the model of meta-ethnography and follows thematic synthesis procedures. Twenty-two studies are included, reporting on the view of 580 participants. Three main themes emerge: (i) What lacks, (ii) Some expectations but no request, and (iii) How to address the issue and induce patients’ motivation. Our results reveal a global feeling of a lack of legitimacy among PCPs when it comes to addressing the issue of tobacco and smoking cessation with their patients, even though they have developed creative strategies based on what is at the core of their practice, that is proximity, continuity, long-term and trustworthy relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tobacco use kills up to half of those who use it (more than 8 million people a year), and there may be 1.1 billion smokers across the planet. Addiction to smoked tobacco depends on nicotine and involves an interplay of many factors (pharmacological, genetics, social, environmental, psychological, behavioral) resulting in an uncontrollable need to smoke so to modulate mood and arousal and relieve withdrawal symptoms. Over the past 20 years, the total number of people using tobacco worldwide has begun to fall for the first time, by around 60 million (from 1.397 billion in 2000 to 1.337 billion in 2018)1. This reduction is the result of comprehensive measures and actions undertaken at the national and international levels.

Smoking cessation intervention programs—such as the 5A approach—Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange2,3, the motivational interviews4,5 and brief advice—have shown efficacy, but among specific populations or in specialized clinical settings6,7. Professional support and cessation interventions or medications increase significantly the chance of successful quitting, while without support 95% of attempts to quit will fail1.

The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that primary health care is the most suitable health setting for providing advice and support on smoking cessation8, as it provides frequent and important opportunities to identify tobacco use, provide advice and help people to quit9,10. Yet, despite being an opportunistic and trustworthy setting11,12, many smokers do not receive support from their primary care providers (PCPs)13, since only a few of them have received training in delivering specific interventions14, and most of the patients come in daily clinical practice without an explicit demand of quitting.

Most of the national guidelines focus either only on “smokers who want to stop”15, or are based on the 5A-approach supposedly covering every stage of the process16,17. There are many guidelines for smoking cessation in primary care—clinical practice guidelines, national recommendations, public health policies; they all address the need to identify smokers, to deliver behavior change intervention, to advise patients to quit, and offer cessation interventions or medications17,18,19,20. However, some inconstancies and gaps within the guidelines need to be underlined: (i) these recommendations do not detail how PCPs should do to achieve these goals, (ii) only a few of them, among guidelines from 22 countries, have involved PCPs directly in their development21, (iii) only two guidelines have included recommendations for “a person who smokes [and] is not ready to quit”22,23, based on prevention campaigns main lines—understanding the risk and encouragement to seek help to stop—and taking into account the patient’s own time frame and personal needs and goals22.

Quantitative literature focuses mostly on the smoking cessation phase24,25,26,27,28, the obstacles professionals encounter in initiating smoking cessation treatment29,30, and the question of prevention31,32,33. Conducting qualitative research is becoming essential in the field of addiction in general, tobacco addiction in particular, in order to better inform policies by more patient and public involvement. Qualitative studies are relevant to explore complex issues such as tobacco use and to find new ways to improve smoking cessation outcomes in primary settings through in-depth descriptions of the lived experience of PCPs and patients in great depth. Because qualitative studies are usually conducted with small samples and in specific contexts, there may often be concerns about the generalizability of their results. Synthesizing data from qualitative studies can help in the development of health policies and clinical practices. Yet, to date, no systematic review of this qualitative literature has ever been conducted.

We thus conducted a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies34,35 in order to explore the lived experience of both PCPs and smokers regarding tobacco use and smoking cessation when meeting in this specific setting.

Results

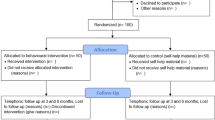

Of the 10940 articles initially retrieved, 22 studies were included (Fig. 1). Participants were patients (N = 325) (current smokers N = 289, ex-smokers N = 36) and primary care providers (N = 255) (nurses N = 50; including 31 smokers), general practitioners (N = 159), residents (N = 14), dentists (N = 23)).

These studies came from six English-speaking countries. Table 1 describes the global characteristics of the included studies (Supplementary Table 1 describes the characteristics of each study).

The quality appraisal showed that the overall quality of the studies was high (Table 2, Supplementary Table 2). Several papers failed to address the role of the researchers’ contribution to the findings and/or interpretations (reflexivity item, 21 studies). The CERQual assessment of the findings showed “high confidence” or “moderate confidence” in most of the categories (Supplementary Table 3).

Three central themes emerged from the analysis: (i) What lacks (ii) Some expectations but no request and (iii) How to address the issue and induce patients’ motivation. Supplementary Table 4 presents excerpts of transcripts quoted in the articles studied, selected to exemplify the results described.

What lacks

Patients, PCPs, and authors enumerated many things that lacked in order to successfully lead patients to an active or specialized smoking cessation intervention.

Patients’ lack of motivation

Patients described a lack of internal motivation to stop smoking and stated that their own will and motivations were the key to quit36. Many were ambivalent about quitting smoking or not, rationalizing between some negative aspects (health, cost…) and positive ones (pleasure, habit…)37.

PCPs’ lack of sincerity and adequacy

Some professionals felt that they were not in a position to raise the subject because they smoked themselves. They described a feeling of hypocrisy and felt uncomfortable and inadequate38,39. Many nurses who were smokers denied participating directly in habit-breaking therapies since they felt uncomfortable helping others to break a habit they could not control themselves38.

Lack of support

The authors reported a lack of institutional support40. Some PCPs described a feeling of solitude because they had to handle these issues completely on their own40.

Lack of time and of a common time frame

Because of their workload, PCPs lacked time to enter into a time-consuming process of initiating and providing support to their patients with tobacco addiction from a “no-request” position to smoking cessation interventions41,42,43.

Lack of skills and training

Many PCPs considered their skills in this area to be mediocre and their knowledge inadequate; they also described a feeling of poor self-efficacy40,44,45.

Some expectations but no request

In these studies, patients described having different kinds of expectations related to their tobacco use when meeting PCPs, even if they did not disclose any explicit request. Accordingly, PCPs did not act the same in front of this absence of a request.

Patients’ expectations about PCPs

Some patients expected nothing from their PCPs, that is, they did not want any advice or even the subject to be raised in consultations39,41,46. They argued that their tobacco use problem was their problem only and their own responsibility43 and that quitting was only a matter of their own will to start the process47. Similarly, other patients stated that the “smoking cessation topic” was to be initiated by themselves only and not by PCPs, except when it was directly relevant to the medical issue they were seeking help for. Some PCPs in these studies shared this view44. However, other patients, in line with most of the PCPs in these studies, considered that PCPs were doing their “duty” when systematically exploring smoking status and habits43. According to some patients, tobacco use needed to be a topic regularly and routinely discussed during consultations41. Patients expected from PCPs to show support and motivation the moment they would ask for help41. That echoes a commune PCPs attitude in these studies, not acting before a request but be proactive and supportive as soon as a patient explicitly stated that he/she wanted to quit smoking43.

Patients expected PCPs to respect their own rhythm and timing48. According to some authors, both patients and PCPs valued a non-moralist and non-judgmental approach, so patients could feel free to speak about everything48.

Finally, many patients expected an active role from PCPs49,50: to give advice to every patient about smoking46,47,48,51 and to provide education, information, and smoking cessation options41,49. Some patients explained that they were too ashamed to admit they were smoking and would not be able to raise the issue by themselves49. According to the patients, general practitioners (GPs) were at the best place to initiate the process—better than specialized clinics-, since they knew the patients the best and had an established ongoing relationship with them41,46,51,52.

PCPs roles and attitude

All the PCPs included in the studies were fully aware that they had a role to play in their patients’ smoking cessation process. Yet, they did not agree on which role and the level of involvement and responsibility they needed to have.

Some PCPs limited themselves to the following objective: to plant a seed for the long term40,53. GPs considered their role was to provide advice and referral to the nurses for assistance, but not to motivate every smoker to stop smoking43. They felt the burden was out of their hands after advising43.

As already mentioned, a common attitude among PCPs was to wait for an explicit request. PCPs wanted to preserve the therapeutic alliance and addressed smoking issues only if patients initiated the talk first41,54. These PCPs met the patients’ expectations to respect their rhythm and timing and to offer professional support as soon as the patients requested it48.

Finally, many PCPs in general, and GPs in particular, felt they had a responsibility toward their patients who used tobacco. The question was not if it was their role to support smoking cessation, but how they should do it42: investigating patients’ smoking status, as part of a routine intake or annual physical41, providing advice and options43, educating people about the smoking health outcomes41, but also inducing motivation to quit.

How to address the issue and induce patients’ motivation

Timing and temporality: the right moment

Both patients and PCPs underlined the impact of finding the right moment to speak about smoking cessation, that is either when the patient was ready to speak about it48,55 or when the context of the consultation made it a relevant issue to address, for instance when patients had a disorder potentially aggravated by smoking, such as asthma, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, or periodontal problems41,42,51,56. The authors described the concept of a ‘teachable moment’56.

Familiarity, continuity, and trust

What appeared predominantly was the importance of the relational aspects among patients and PCP. Many patients underlined the unique relation of trust they had with their GPs51,52. A long-term relationship, based on long acquaintance and familiarity42, and a genuine dialog between professionals and patients were seen as key factors and therapeutic levers to enhance smoking cessation40. Authors mentioned “ongoing, longitudinal relationships with patients”57, building trust over time40,46, as an efficient way to reinforce success or to suggest other solutions to overcome the failures and to take the advice given acceptable and “hearable“46. Therapeutic relationship was the most salient result for several authors40,49. Some nurses who were smokers even thought that their tobacco use could facilitate the therapeutic relationship38.

Strategies and approaches

Both patients and PCPs have experienced many strategies and approaches.

Testing the water, small talk, or holistic method

For patients, good practices involved using a respectful tone, sensitivity to the patient’s receptivity, understanding the patient as an individual, being supportive, and neither “preaching”47, nor “pushing”41. On that matter, some PCPs used a “testing the water” strategy, that is to introduce the subject in “baby steps“58—using verbal and non-verbal cues to assess whether patients were motivated to stop smoking or not57—or “small talk”42 taking every opportunity to provide the information, especially with humor40. Others described raising the question of smoking as part of a holistic approach to medicine42,54.

Rational strategy and tangible link

Motivation for quitting resulted from personal impact and tangible prompts, when patients could physically see the damage caused by smoking56. PCPs used a rational strategy linking patients’ symptoms to their smoking42,58 and thus legitimizing the fact they had to address this issue49.

A “collaborative strategy”

Both underlined the importance of PCPs having an approach, based on respect and comprehension41,47,51. PCPs considered this approach as part of a relationship of trust that supports, encourages, and sustains behavioral change, with an idea of mutuality in the conversation40,46,48,58. Moreover, both expressed the need for more direct and more frequent verbal discussions48,51. For example, PCPs could open a discussion by stating that they were aware that the patient had earlier said “no” and that they just wanted to know if the patient had changed his/her mind48.

A “confrontational strategy”

Few patients suggested that PCPs should try to scare them into quitting, with visual images illustrating the health consequences of smoking. Yet, paradoxically, the same patients stated they would not quit if confronted by a major personal smoking health shock47. This confrontation strategy was described by PCPs as “firm”, “strong”, “more direct”, “more forceful,” and “telling patients off,” but also criticized as nagging”58. Some underlined rigor and direct communication40, others “scare tactics” to highlight the harmful effects of smoking44.

Patient-centered approach

Patients valued the advice given in an individualized context, if not they would associate them with a public health campaign and would not feel personally concerned41,47,49. Patients without request felt neither listened to nor recognized when PCPs focused on their smoking54. PCPs also underlined a more tailored approach44.

Educational approach

Several patients pointed out that materials should be available for review before meeting with the PCP51. Many PCPs described educating their patients on the health risks of smoking44.

Using addiction model

Patients recognized smoking as a serious addiction51 and many PCPs used it as a way to address it, recognizing the addictiveness of nicotine and the difficulty of quitting41.

Patients finally suggested two strategies unfound among PCPs: positive and targeted messages37,51 and carbon monoxide monitoring51.

Discussion

Our results underlined the many obstacles perceived by the PCPs and the patients, but also the creative strategies used by PCPs in their daily practice.

Many obstacles are already addressed in the literature: lack of clinician engagement, lack of clarity of the policies and guidelines, lack of time, lack of resources, lack of managerial support, lack of training, healthcare professionals’ negative beliefs59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66. PCPs workload and increasing number of patients impose them very often to reduce the time of their appointments67. Addiction medicine is not mandatory in GPs—and other PCPs—training and when integrated, only a little time in the curriculum is devoted to substance use disorders and addictions68. As for specific training regarding tobacco use addiction, many models, tools and theories have been developed and can be applied in PCPs daily practice, for instance, the 5As and 5Rs—to both assist smokers willing to quit (5As) and implement interventions designed to increase future attempts with patients unwilling to quit at the time of the visit (5Rs)69, or the transtheoretical model by Prochaska and DiClemente70, the label “teachable moment”2,71 and “opportunistic smoking cessation interventions”72, such as the “ flashcard for a motivational-based intervention” tool, taking only 30 s to 3 min to use73. Moreover, some national public health policies directly target and compel healthcare professionals to deliver opportunistic health behavior change interventions to patients during routine medical consultations, for instance, the “Making Every Contact Count”74 campaign in the United Kingdom75. Yet, a study has shown that only 31,4% PCPs had heard about this policy76. As a matter of act, rates of tobacco treatment delivery in primary care are quite low77, research has shown that PCPs had a suboptimal adherence to smoking cessation guidelines78, and that, even informed less than 50% of them, in only 50% of occasions, would offer adjunct support to patients73,76,79.

All of these obstacles and difficulties, plus the fact that some PCPs are smokers themselves, contribute to an overall feeling of a lack of legitimacy.

This is an original and unexpected point raised by our metasynthesis that would need further research. This encounter between PCPs feeling not legitimate and a smoker who has neither a request nor motivations to quit could explain why, opportunities created by a primary care setting are very often missed, despite all the specific guidelines, tools, and policies73,80,81,82. However, our results show that smokers do perceive PCPs as legitimate and at the right place to address their tobacco issue. This strengthens the positions of several quantitative studies73,83. Most of the patients expect help from PCPs regarding their tobacco addiction. Moreover, what makes PCPs legitimate to help their patients who are smokers is not related to any specific skills or knowledge in addiction, psychiatry, or psychotherapies, but to what is the core of PCPs practice, that is proximity, continuity, long-term and trustworthy relationships. Ideally, all PCPs should receive proper addiction medicine training, but their role is not to be an attenuated version of a tobacco specialist or a therapist. In other words, rather than focusing on addressing what lacks, we should focus on PCPs specific knowledge and skills. PCPs expertize and specific relation with the patients make the primary care setting a relevant opportunistic situation to initiate and support patients’ smoking cessation84. PCPs need to be aware of their important role and allow more time to this important task72. They need to overcome their feeling of illegitimacy and the absence of patients’ request84 and focus on how inducing a will to quit to a patient who came to visit them for another reason.

Our results suggest some practical implications for PCPs when meeting a patient who is a smoker:

-

(i) being proactive without waiting for patients explicit request while taking into account their own time frame and personal needs and goals22;

-

(ii) integrating the tobacco use as a regular and routine issue to discuss in the global assessment of the patient’s daily life84;

-

(iii) investigating the relationship the patients are entertaining with its tobacco use not in a binary way (to want to quit or not, to be motivated or not) but with open questions—what is it for you to be a smoker? what do you think of your tobacco use?—so to explore pros and cons, doubts, worries, and expectations.

Yet caution will be required to transpose these practical implications in cultural contexts not represented in the studies included. Conducting implementation research and transcultural studies to ensure their local relevance would be necessary.

Further qualitative and quantitative research is necessary to in-depth explore the feeling of illegitimacy among PCPs and to better integrate PCPs specific skills and competencies in guidelines, so they can truly be in the frontline to effectively prevent tobacco addiction and its harmful effects.

This metasynthesis includes the experience of 325 participants. The method we applied is rigorous, has been tested in medical research85, and meets the criteria of the ENTREQ guidelines86.

Nonetheless, certain aspects of this metasynthesis limit the generalization of its conclusions. A qualitative metasynthesis collects only partial data from the participants and the interpretations of the researchers, which are the data given in the initial articles. Moreover, although the review assembled articles from diverse cultural areas, English-speaking countries are overrepresented as we restricted our selection to articles in that language. That’s why the conclusions of this study might be restricted to this cultural area.

Finally, the results of the studies included in this metasynthesis were redundant from a methodological perspective. More participatory research methods are needed to involve professionals and patients so to reach more original and relevant results.

Methods

This meta-synthesis relies on the model of meta-ethnography35 and follows the thematic synthesis procedures described by Thomas and Harden34.

Inclusion criteria were as followed.

Participants

We selected studies exploring tobacco issues among patients who smoke and PCPs (either doctors, nurses, dentists, etc…), i.e., the stakeholders involved in this encounter. In order to remain as close as possible to daily practice in primary care settings, we decided not to include PCPs with specific training—both theoretical (about tobacco or addiction) and practical (specific interventions) or any tobacco-related specialist (PCPs working in tobacco clinics, pneumonologist, addiction specialist).

Outcomes

Participants reported experiences during primary care consultations about the issue of tobacco use and smoking cessation.

Studies

Qualitative studies, based on a well-known qualitative methodology and using specific data collection tools and data analytical procedures (Table 3).

As for exclusion criteria, we excluded studies including healthcare providers who were specifically trained in smoking cessation interventions or working in tobacco-related settings. Studies that focused on the perinatal period were not included because that would require a metasynthesis on its own (Table 3).

Search Strategy involved screening from four databases: MEDLINE, PsycInfo, CINAHL, and SSCI from April through November 30, 2019, with an update in October 2020 (Supplementary Table 5). Preliminary research had identified several articles from which we selected keywords. Extensive lateral searches also sought to identify papers that might have eluded our algorithms.

Study selection was done after collecting the references and eliminating duplicates, two authors (J.S. and E.M.) subsequently read the titles and abstracts to assess their relevance. The potentially relevant articles were then read in full, and a second selection made to keep only the articles that met our inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved during meetings of the research group.

Two authors (E.M., J.S.) assessed the quality of included articles independently by applying the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) criteria to each (Table 3; Supplementary Table 2).

Then they discussed the results within the research group until an agreement was reached. No study was excluded from the analysis based on this evaluation.

One researcher (E.M.) extracted the formal characteristics of the studies and three (J.S., E.M., and A.R.L.) independently and exhaustively extracted the first-order results (that is, the study results) and the second-order results (the authors’ interpretations and discussions of the results) in the form of a summary for each study we included (Supplementary Fig. 1). We endeavored to preserve the context of the studies included by reporting the essential characteristics of each.

Qualitative data were analyzed thematically relied on an inductive and rigorous process. Three researchers (E.M., J.S., A.R.L.) independently and simultaneously conducted a descriptive analysis intended to convey the participants’ experience—from their own perspective and that of the authors. This involves, for each article and each researcher: (1) reading the summaries related to the article; (2) open coding each summary into—not predetermined—descriptive units; (3) categorizing the units, that is, regrouping them accordingly to their proximity of meaning and experience. These stages were carried out with the help of N’Vivo-12 software (QSR International). Progressively, each researcher conducted a cross-sectional analysis of all of the data analyzed thus far, by regrouping similar categories and excluding none of them. After this analysis, the three researchers met with the rest of the research group —who had read and become familiar with the data during this time—to share the categories uncovered. During these two-hour meetings, the group performed the work of translation, that is comparing and assembling the categories obtained by the analysis of each article to develop the key themes that captured similar ideas from the different articles and then to develop overarching concepts about the research question. In practice, the group had to: (1) regroup the categories into themes, a reorganization that uncovered the framework of the participants’ experience; (2) determine the key themes, that is, the most significant and relevant themes. Only four meetings were necessary to obtain the results as the level of agreement of those meetings was high. The high level of rigor of the results was obtained by triangulation of both the data sources and the analyses: three independent analyses and regular research meetings.

The CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) GRADE approach87 was used to assess confidence in the findings of the metasynthesis, following four key components: methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy of the data (Supplementary Table 3).

Assessment of these four components enabled us to reach a judgment. about the overall confidence for each review findings, that is, each category in our results, rated as high, moderate, low, and very low, with “high confidence” being the starting assumption88.

Data availability

All relevant data are available upon relevant and reasonable request. Researchers who are interested can write to the corresponding author of this publication jordansib@hotmail.com.

References

WHO. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/19-12-2019-who-launches-new-report-on-global-tobacco-use-trends. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2019).

Lawson, P. J. & Flocke, A. S. Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 76, 25–30 (2009).

Satterfield, J. M. et al. Computer-facilitated 5A’s for smoking cessation: a randomized trial of technology to promote provider adherence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 55, 35–43 (2018).

Heckman, C. J., Egleston, B. L. & Hofmann, M. T. Efficacy of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob. Control 19, 410–416 (2010).

Frost, H. et al. Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 13, e0204890 (2018).

McWilliams, L., Bellhouse, S., Yorke, J., Lloyd, K. & Armitage, C. J. Beyond ‘planning’: a meta-analysis of implementation intentions to support smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 38, 1059–1068 (2019).

Chen, D. & Wu, L. T. Smoking cessation interventions for adults aged 50 or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1, 14–24 (2015).

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2021. (2003).

Royal College of General Practitioners. The 2022 GP. Compendium of Evidence. Royal College of General Practitioners, London. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/ ~/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/The-2022-GP-Compendium-of-Evidence.ashx. Accessed 10 Feb 2016. (2013).

Tønnesen, H. et al. Smoking and alcohol intervention before surgery: evidence for best practice. Br. J. Anaesth. 102, 297–306 (2009).

Richmond, R., Kehoe, L., Heather, N., Wodak, A. & Webster, I. General practitioners’ promotion of healthy life styles: what patients think. Aust. N. Z. J. Pub. Health 20, 195–200 (1996).

Duaso, M. & Cheung, P. Health promotion and lifestyle advice in general practice: what do patients think? J. Adv. Nurs. 39, 472–479 (2002).

Abi-Fadel, F., Gorga, J. & Fahmy, S. Smoking cessation counselling: who does best pulmonologists or GPs? Prim. Care. Respir. J. 22, 17–18 (2013).

Carson, K. V. et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2. Issue 5. Art. No.:CD000214. (2012).

HAS: Haute Autorité de Santé. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1718021/fr/arret-de-la-consommation-de-tabac-du-depistage-individuel-au-maintien-de-l-abstinence-en-premier-recours. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2020).

Can-ADAPTT: Canadian Action Network for the Advancement, Dissemination and Adoption of Practice-informed Tobacco treatment. https://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/en/canadaptt/PublishingImages/Pages/CAN-ADAPTT-Guidelines/CAN-ADAPTT%20Canadian%20Smoking%20Cessation%20Guideline_website.pdf. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2020).

RACGP: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/supporting-smoking-cessation. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2020).

Whitlock, E. P., Orleans, C. T., Pender, N. & Allan, J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am. J. Prev. Med. 22, 267–284 (2002).

Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/. (2017, November 8).

Van Schayck, O. et al. Treating tobacco dependence: guidance for primary care on life-saving interventions. Position statement of the IPCRG. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 27, 38 (2017).

Verbiest, M. et al. National guidelines for smoking cessation in primary care: a literature review and evidence analysis. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 27, 2 (2017).

NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng92. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2020).

NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.government.nl/documents/reports/2019/06/30/the-national-prevention-agreement. Accessed 1 Jan 2020. (2019).

Chavarria, J., Liu, M., Kast, L., Salem, E. & King, A. C. A pilot study of Counsel to Quit®: evaluating an Ask Advise Refer (AAR)-based tobacco cessation training for medical and mental healthcare providers. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 99, 163–170 (2019).

Meijer, E., der Kleij, Van, Segaar, R. & Chavannes, D. N. Determinants of providing smoking cessation care in five groups of healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional comparison. Patient Educ. Couns. 102, 1140–1149 (2019).

Coovadia, S. et al. Catalyst for change: measuring the effectiveness of training of all health care professionals to provide brief intervention for smoking cessation to cancer patients. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 51, 7–11 (2019).

Utap, M. S., Tan, C. & Su, A. T. Effectiveness of a brief intervention for smoking cessation using the 5A model with self-help materials and using self-help materials alone: a randomised controlled trial. Malays. Fam. Physician 14, 2–9 (2019).

Sheeran, P. et al. What works in smoking cessation interventions for cancer survivors? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 38, 855–865 (2019).

Jradi, H. Awareness, practices, and barriers regarding smoking cessation treatment among physicians in Saudi Arabia. J. Addict. Dis. 36, 53–59 (2017).

Harutyunyan, A., Abrahamyan, A., Hayrumyan, V. & Petrosyan, V. Perceived barriers of tobacco dependence treatment: a mixed-methods study among primary healthcare physicians in Armenia. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 20, e17 (2019).

Shaik, S. S., Doshi, D., Bandari, S. R., Madupu, P. R. & Kulkarni, S. Tobacco use cessation and prevention–a review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10, ZE13–ZE17 (2016).

Golechha, M. Health promotion methods for smoking prevention and cessation: a comprehensive review of effectiveness and the way forward. Int. J. Prev. Med. 7, 7 (2016).

Nilsson, P. M. Better methods for effective smoking cessation are necessary. Prim. Health Care 104, 2412–2413 (2007).

Thomas, J. & Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 45 (2008).

Atkins, S., Lewin, S., Smith, H., Fretheim, A. & Volmink, J. Conducting a metaethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 21 (2008).

Bartlett, Y. K., Gartland, N., Wearden, A., Armitage, C. J. & Borrelli, B. “It’s my business, it’s my body, it’s my money”: experiences of smokers who are not planning to quit in the next 30 days and their views about treatment options. BMC Public Health 15, 716 (2016).

González, S., Bennasar, M., Pericàs, J., Seguí, P. & De Pedro, J. Spanish primary health care nurses who are smokers: this influence on the therapeutic relationship. Int. Nurs. Rev. 56, 381–386 (2009).

Heath, J., Andrews, J., Kelley, F. J. & Sorrell, J. Caught in the middle: experiences of tobacco-dependent nurse practitioners. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pr. 16, 396–401 (2004).

Andersson, P., Westergren, A. & Johannsen, A. The invisible work with tobacco cessation-strategies among dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 10, 54–60 (2012).

Bell, K., Bowers, M., McCullough, L. & Bell, J. Physician advice for smoking cessation in primary care: time for a paradigm shift? Crit. Public Health 22, 9–24 (2011).

Guassora, A. D. & Baarts, C. Smoking cessation advice in consultations with health problems not related to smoking? Relevance criteria in Danish general practice consultations. Scan J. Prim. Health Care 28, 221–228 (2010).

Van Rossem, C. et al. Smoking cessation in primary care: Exploration of barriers and solutions in current daily practice from the perspective of smokers and healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Gen. Pr. 21, 111–117 (2015).

Champassak, S. L. et al. A qualitative assessment of provider perspectives on smoking cessation counselling. J. Eval. Clin. Pr. 20, 281–287 (2014).

Kerr, S., Watson, H. & Tolson, D. An exploration of the knowledge, attitudes and practice of members of the primary care team in relation to smoking and smoking cessation in later life. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 8, 68–79 (2007).

Wilson, A. et al. Management of smokers motivated to quit: a qualitative study of smokers and GPs. Fam. Pr. 27, 404–409 (2010).

Butler, C. C., Pill, R. & Stott, N. C. Qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of doctors’ advice to quit smoking: implications for opportunistic health promotion. BMJ 316, 1878–1881 (1998).

Guassora, A. D. & Tulinius, A. C. Keeping morality out and the GP in. Consultations in Danish general practice as a context for smoking cessation advice. Patient Educ. Couns. 73, 28–35 (2008).

Buczkowski, K., Marcinowicz, L., Czachowski, S., Piszczek, E. & Sowinska, A. “What kind of general practitioner do I need for smoking cessation?” Results from a qualitative study in Poland. BMC Fam. Pr. 14, 159 (2013).

Pilnick, A. & Coleman, T. “I’ll give up smoking when you get me better”: patients’ resistance to attempts to problematise smoking in general practice (GP) consultations. Soc. Sc. Med. 57, 135–145 (2003).

Halladay, J. R. et al. Patient perspectives on tobacco use treatment in primary care. Prev. Chronic Dis. 12, E14 (2015).

Chean, K. Y. et al. Barriers to smoking cessation: a qualitative study from the perspective of primary care in Malaysia. BMJ Open 9, e025491 (2019).

Nowlin, J. P., Lee, J. G. L. & Wright, W. G. Implementation of recommended tobacco cessation systems in dental practices: a qualitative exploration in northeastern North Carolina. J. Dent. Educ. 82, 475–482 (2018).

Guassora, A. D. & Gannik, D. Developing and maintaining patients’ trust during general practice consultations: the case of smoking cessation advice. Patient Educ. Couns. 78, 46–52 (2010).

Lin, A. & Ward, P. R. Resilience and smoking: the implications for general practitioners and other primary healthcare practitioners. Qual. Prim. Care 20, 31–38 (2012).

Holliday, R. et al. Perceived influences on smoking behaviour and perceptions of dentist‐delivered smoking cessation advice: A qualitative interview study. Com. Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 48, 433–439 (2020).

Coleman, T. & Murphy, E. & Cheater, F. Factors influencing discussion of smoking between general practitioners and patients who smoke: a qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 50, 207–210 (2000).

Coleman, T., Cheater, F. & Murphy, E. Qualitative study investigating the process of giving anti-smoking advice in general practice. Patient Educ. Couns. 52, 159–163 (2004).

Vogt, F., Hall, S. & Marteau, T. General practitioners’ and family physicians’ negative beliefs and attitudes towards discussing smoking cessation with patients: a systematic review. Addiction 100, 1423–1431 (2005).

Chisholm, A., Hart, J., Lam, V. & Peters, S. Current challenges of behavior change talk for medical professionals and trainees. Patient Educ. Couns. 87, 389–394 (2012).

Bonner, C. et al. How do general practitioners and patients make decisions about cardiovascular disease risk? Health Psychol. 34, 253–261 (2015).

Jansen, J. et al. General practitioners’ decision making about primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in older adults: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 12, e0170228 (2017).

Lowson, K. et al. Examining the implementation of NICE guidance: cross-sectional survey of the use of NICE interventional procedures guidance by NHS Trusts. Implement. Sci. 10, 93 (2015).

Weng, Y. H. et al. Implementation of evidence-based practice across medical, nursing, pharmacological and allied healthcare professionals: a questionnaire survey in nationwide hospital settings. Implement. Sci. 8, 112 (2013).

Elwell, L., Povey, R., Grogan, S., Allen, C. & Prestwich, A. Patients’ and practitioners’ views on health behaviour change: a qualitative study. Psychol. Health 28, 653–674 (2013).

Elwell, L., Powell, J., Wordsworth, S. & Cummins, C. Health professional perspectives on lifestyle behaviour change in the paediatric hospital setting: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 14, 71 (2014).

BMJ. Primary care consultations last less than 5 min for half the world’s population: but range from 48 seconds in Bangladesh to 22.5 min in Sweden. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 12, 2021 www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/11/171108215721.htm (2021).

Klimas, J. & Cullen, W. Better addiction medicine education for doctors and allied health professions: a toolkit. UCD School of Medicine. (link to online version https://youtu.be/vlHf88dkjCQ) (2020-08).

Giulietti, F. et al. Pharmacological approach to smoking cessation: an updated review for daily clinical practice. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 27, 349–362 (2020).

Prochaska, J. O. & DiClemente, C. C. Stage and processes of self change of smoking: Toward and integrative model. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 51, 390–395 (1983).

McBride, C. M., Emmons, K. M. & Lipkus, I. M. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ. Res. 18, 156–170, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/18.2.156 (2003).

Keyworth, C., Epton, T., Goldthorpe, J., Calam, R. & Armitage, C. J. Delivering opportunistic behavior change interventions: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Prev. Sci. 21, 319–331 (2020).

McIvor, A. et al. Best practices for smoking cessation interventions in primary care. Can. Respir. J. 16, 129–134 (2009).

Public Health England. Making Every Contact Count (MECC): Consensus statement, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/769486/Making_Every_Contact_Count_Consensus_Statement.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2020. (2016).

NHS: National Health Service, Yorkshire and the Humber. Prevention and Lifestyle Behaviour Change: A Competence Framework. https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/media/1017/011-prevention-and-lifestyle-behaviour-change-a-competence-framework.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2020. (2010).

Keyworth, C., Epton, T., Goldthorpe, J., Calam, R. & Armitage, C. J. Are healthcare professionals delivering opportunistic behaviour change interventions? A multi-professional survey of engagement with public health policy. Implement. Sci. 13, 122 (2018).

Girvalaki, C. et al. Training general practitioners in evidence-based tobacco treatment: an evaluation of the Tobacco Treatment Training Network in Crete (TiTAN-Crete) intervention. Health Educ. Behav. 45, 888–897 (2018).

De Ruijter, D., Smit, E. S., De Vries, H., Goossens, L. & Hoving, C. Understanding Dutch practice nurses’ adherence to evidence-based smoking cessation guidelines and their needs for web-based adherence support: results from semistructured interviews. BMJ Open 7, e014154 (2017).

Matouq, A. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and behaviors of health professionals towards smoking cessation in primary healthcare settings. Trans. Behav. Med. 8, 938–943 (2018).

Zeev, Y. B. et al. Opportunities missed: a cross-sectional survey of the provision of smoking cessation care to pregnant women by Australian general practitioners and obstetricians. Nicotine Tob. Res. 19, 636–641 (2017).

Nelson, P. A. et al. ‘I should have taken that further’-missed opportunities during cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with psoriasis in UK primary care settings: a mixed-methods study. Health Expect. 19, 1121–1137 (2016).

Van Dillen, S. M., Noordman, J., Van Dulmen, S. & Hiddink, G. J. Examining the content of weight, nutrition and physical activity advices provided by Dutch practice nurses in primary care: analysis of videotaped consultations. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 50–56 (2014).

Bartsch, A.-L., Härter, M., Niedrich, J., Brütt, A. L. & Buchholz, A. A systematic literature review of self-reported smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. PLoS ONE 11, e0168482, (2016).

Vijayaraghavan et al. Disparities in receipt of 5As for smoking cessation in diverse primary care and HIV clinics. Prev. Med. Rep. 6, 80–87 (2017).

Aveyard, P., Begh, R., Parsons, A. & West, R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction 107, 1066–1073 (2012).

Zimmer, L. Qualitative meta-synthesis: a question of dialoguing with texts. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 311 (2006).

Tong, A., Flemming, K. & McInne, E. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12, 181 (2012).

Lewin, S. et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 13, 2 (2018).

Lewin, S. et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 2: how to make an overall CERQual assessment of confidence and create a Summary of Qualitative Findings table. Implement. Sci. 13, 10 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jo Ann Cahn for translating the manuscript. This work was supported by IReSP Institut de recherche en santé publique within the call for project to reduce and fight against smoking 2018. (Nb: APA19002HSA, reference TABAC-V3-09) as part of the research project “Influence des références théoriques et du sTAtut taBAgique des médecins et des Infirmières sur le sevrage Des patiEnts fumeurs (TABACIDE)”. The ethics evaluation committee of Inserm, the Institutional Review Board (IRB00003888, IORG0003254, FWA00005831), has reviewed and approved the research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M. and J.S. are the co-first authors of the article. L.V. and L.J. are co-senior authors. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data: L.J., A.R.L., E.M., J.S., L.V. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: J.S., E.M., L.V., A.R.L. Final approval of the completed version: all authors. Accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: M.T., L.J., L.V., A.R.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manolios, E., Sibeoni, J., Teixeira, M. et al. When primary care providers and smokers meet: a systematic review and metasynthesis. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 31, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00245-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00245-9

This article is cited by

-

Implementation strategies to increase smoking cessation treatment provision in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies

BMC Primary Care (2023)

-

Attitudes & behaviors toward the management of tobacco smoking patients: qualitative study with French primary care physicians

BMC Primary Care (2022)