Abstract

Asthma imposes a substantial burden on individuals and societies. Patients with asthma need high-quality primary care management; however, evidence suggests the quality of this care can be highly variable. Here we identify and report factors contributing to high-quality management. Twelve primary care global asthma experts, representing nine countries, identified key factors. A literature review (past 10 years) was performed to validate or refute the expert viewpoint. Key driving factors identified were: policy, clinical guidelines, rewards for performance, practice organisation and workforce. Further analysis established the relevant factor components. Review evidence supported the validity of each driver; however, impact on patient outcomes was uncertain. Single interventions (e.g. healthcare practitioner education) showed little effect; interventions driven by national policy (e.g. incentive schemes and teamworking) were more effective. The panel’s opinion, supported by literature review, concluded that multiple primary care interventions offer greater benefit than any single intervention in asthma management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic condition that is estimated to affect 339 million people worldwide1,2. Despite major advances in asthma treatment and the availability of both global2 and national guidance, asthma continues to cause a substantial burden in terms of both direct and indirect costs1. In 2016, estimated worldwide asthma deaths were 420,0001 and although there have been falls in some countries over the last decade, significant numbers of avoidable deaths still occur3. Mortality rates vary widely, with low- and middle-income countries faring worse4. For example, Uganda’s reported mortality rate is almost 50% higher5 than that reported globally (0.19/100,000)6, although inter-country comparisons using different data sources and epidemiological methodologies have limitations. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has a global ambition for universal healthcare coverage by 2030 as millions of people worldwide do not have accessible affordable medical care7. The WHO moreover recognises that health systems with strong primary care have the utmost potential to deliver improved health outcomes, greater efficiency and high-quality care7. Perversely the availability of good quality primary and social care tends to vary inversely, those having the greatest needs being least likely to receive it8.

In addition to the issues of access and the quality of care, both under- and over-diagnosis of asthma is common in all healthcare settings, but the issue is of particular concern in primary care, where most initial diagnoses are made9,10.

For people with asthma, high-quality, local and accessible primary care could be a solution to poor control11. Our aim was to identify the factors that experts believe enable the delivery of high-quality asthma care and to review the evidence that confirms that these factors do indeed have positive outcomes in primary care.

Results

Key drivers and their underpinning components

The expert panel identified five key drivers for the delivery of quality respiratory care in primary care and a number of components underpinning each of these drivers. These are summarised in Table 1.

Of the 50 articles selected from the review, there were comparatively smaller numbers of publications relating to the impact of National Health Policy and Guidelines. However, there was more substantial evidence relating to the other three key drivers, which is summarised in tabular format (Tables 2–4).

National Health Policy

The expert panel reached an agreement that the political will to prioritise asthma and to support both primary care and respiratory disease were fundamental elements for the achievement of a sustainable change. In their opinion this required national and local programmes supporting the improvements. There was however little evidence published to support this opinion with respect to patient outcome as it is not the area of research that is commonly undertaken. A review of seven national European asthma programmes to support strategies to reduce asthma mortality and morbidity concluded that national/regional asthma programmes are more effective than conventional treatment guidelines12. One of the most well-known and successful national programmes in Europe, which has resulted in reduced morbidity and mortality and decreased costs, is the Finnish National Asthma Programme13. Programmes outside of Europe have also demonstrated the impact that prioritisation of primary care can have on respiratory outcomes. Changing structures and policies in South Africa and in Brazil may start to impact on primary care13,14.

Guidelines

Few studies have explored the extent of adherence to guidelines for asthma management based on data provided directly by GPs. One study aimed to evaluate adherence to GINA guidelines and its relationship with disease control in real life. According to GINA guideline asthma classification, the results indicated overtreatment of intermittent and mild persistent asthma, as well as a general poor adherence to GINA treatment recommendations, despite its confirmed role in achieving a good asthma control15. In the US, nationally representative data showed that agreement with and adherence to asthma guidelines was higher for specialists than for primary care clinicians, but was low in both groups for several key recommendations16.

Reward for performance

Pay-for-performance (P4p) schemes are those that remunerate physicians for achieving pre-defined clinical targets and quality measures—so based on value—that contrasts to schemes that are simply a fee-for-service payment, which pay for volume of activity (Data from Review Table 2). In the UK, primary care has moved towards group practices with P4p compensation in which performance is measured using several defined quality indicators17,18. A systematic review of 94 studies showed increased practice activity but only limited evidence of improvements in the quality of primary care or cost-effectiveness, despite modest reductions in mortality and hospital admissions in some domains18. In another review of seven studies from the US and UK, the effects of financial incentive schemes were found to improve patient’s well-being, whilst the effects on the quality of primary healthcare were found to be modest and variable19.

An evaluation of three primary care incentive models, namely a traditional fee-for-service model, a blended fee-for-service model and a blended capitation model, demonstrated that the quality of asthma care improved over time within each of the primary care models20. The model that combined blended fee-for-service with capitation appears to provide better quality care compared to the traditional fee-for-service model in terms of outcome indicators such as a lower rate of emergency department visits.

A P4p programme in the Netherlands containing indicators for chronic care, prevention, practice management and patient experience was designed by target users21. A study of 65 practices that implemented the programme showed a significant improvement in the mean asthma score after 1 year. It showed that a bottom-up developed P4p programme might lead to improvements in both clinical care and patient experience.

Practice resources and organisation

Optimal patient care requires targeted and tailored management (Data from Review Table 3). The experts felt that the organisation of both the GP practice and the local healthcare system had an influence on the provision of high-quality care. Registered patient lists and fully integrated computer systems were its foundation. An approach called SIMPLES—developed in the UK, incorporated into a desktop reference tool by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group and adapted for use in the Netherlands22,23—identifies patients who have uncontrolled symptoms or difficult-to-manage disease and addresses preventable or treatable factors to guide their management. Electronic alerts in patient records have also been used to identify those at increased risk of an exacerbation, in order to modify care and treatment24,25,26.

A systematic review of the effectiveness of computerised clinical decision systems (CCDS) in the care of patients with asthma demonstrated improvements in healthcare process measures and patient outcomes27. Conversely another systematic review focussing on their implementation in practice concluded that the limiting factors were the lack of their regular use by healthcare practitioners (HCPs) and adherence to the advice offered28. These reviews both concluded that CCDS have the potential to improve patient outcomes, practice efficiency and produce cost-saving benefits if implemented27,28.

Computerised systems linked with internet programmes to monitor asthma control can also afford benefits for patients. One study identified that the use of both weekly internet-based self-monitoring using the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) and treatment adjustment using an online management tool resulted in significant improvements in ACQ29.

Clinical prediction models could theoretically aid the diagnosis of asthma in primary care but supportive evidence is currently lacking30. However, there is strong evidence that service models aimed at supporting primary care practitioners with the diagnosis or ongoing monitoring of patients result in improved accuracy and patient outcomes31,32,33.

Workforce

The expert panel felt that having access to dedicated and appropriately trained personnel preferably as part of multidisciplinary teams was essential (Data from Review Table 4). This need was accentuated because of increasing GP workloads and a shortage of primary care physicians in many countries.

There was extensive evidence34,35,36,37,38,39,40 that a variety of models involving a range of healthcare practitioners within both the core primary healthcare team and extended community teams improve patient outcomes and healthcare process measures—such as an increased use of asthma action plans, improved medication adherence36,39—and reduces the use of emergency care34,38.

One approach in Canada is based on using primary care networks, in which additional non-physician healthcare providers are funded to help provide coordinated healthcare34. In these networks patients were shown to be less likely to visit the ED than patients in practices that were not part of the network.

Evidence from a range of countries supports the beneficial role of pharmacists, working alone or in teams36,37,38. In a study utilising community pharmacists to review patients with either poorly controlled asthma or no recent asthma review, there were benefits in terms of asthma control, inhaler technique, action plan ownership, asthma-related QOL and medication adherence36. The pharmacists were able to recruit patients and incorporate this as part of daily practice. Availability of referral to a physician was an important component of the service.

Evidence also indicates that education delivered by a variety of methods enhances the quality of care delivered and improves patient outcomes41,42,43,44,45. Approaches integrating education with other interventions, such as the Colorado Asthma Toolkit Programme (CATP) that combines education with decision support tools, electronic patient records and other online support materials, have been shown to have positive outcomes41,42. Another team-based approach that combined an educational intervention with the integration of an electronic clinical quality management system with a reminder system found that the number of action plans increased significantly39.

Patient education is an important factor for the improvement of self-management and asthma control. An educational programme from Australia demonstrated that patients who received person-centred education had improved asthma outcomes compared to those receiving a brochure only46. One review paper47 about patient enablement concluded that HCPs need to develop their understanding of this concept to integrate this into practice as the level of this is linked to better patient outcomes.

Discussion

Primary care is pivotal to any health system; however, there is no universal definition of what we mean by primary care and certainly not one standardised model of care. Without focussing on a single model, we have attempted to bring together expert opinion and the most recent evidence on strategies that improve outcomes in asthma patients in primary care. To our knowledge the methodology used in this project has not been used before. The panel of experts who identified the key drivers were knowledgeable of asthma in primary care at a national level in their respective countries and globally. A literature search to investigate the individual key drivers and their underpinning components was undertaken using a keyword search. This identified many publications but very few measured the effect on patient outcome and those that did reported conflicting results. Furthermore, we found a paucity of research relating to the components relating to national healthcare policy and guidelines.

The evidence suggests that health systems that have primary care as a cornerstone and place asthma as a healthcare priority improve asthma care and improve outcome on patient level. The highly regarded Finnish asthma initiative carried out more than 25 years ago not only identified asthma as a national priority, but also placed primary care at the centre of the programme, recognising the key role of General Practitioners and nurses and greatly reduced asthma mortality and morbidity48. After the successful implementation of the Finnish asthma plan, many other countries and regions have attempted to implement similar initiatives13,14. For example, in Poland and Brazil, asthma burden was reduced utilising such a strategy49.

Poor health outcomes in asthma patients have been attributed in primary care to gaps between evidence-based recommendations and practice50,51. Studies show that adherence to clinical guidelines is poor, whatever the clinical setting, with the main barriers being time pressures and limited resources52, reflecting that it is not the guidelines per se that improve care, but it is the implementation of the recommendations.

Most guidelines are complex, lengthy and generally biased towards a secondary care perspective. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) committee acknowledges the difficulty of implementing their recommendations in primary care, but they are almost exclusively developed by tertiary care physicians2. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Royal Society of General Practitioners writes its own guidelines, which are all presented in the same recognisable brief format. Their asthma guidelines were first published in 1986 with revisions every 4 years and are relatively well followed53. However, there are now 194 different clinical guidelines in the Netherlands, illustrating just how difficult it is for General Practitioners to adopt all the recommendations of each clinical guideline and its update.

A survival analysis of guidelines has concluded that 86% are still up to date 3 years after their publication and yet the median lifespan of a clinical guideline is about 60 months54. New evidence is continually emerging and this implies that regular updates of clinical guidelines are necessary55,56. It is therefore important that all guidelines have a process for regular scrutiny57 and are updated for contemporary applicability. Indeed, asthma and COPD guidelines published by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany and the Asthma Guidelines of the German Respiratory Society are regularly updated, at least every 5 years (more frequently as necessary); if not they are deleted from the website.

The proliferation of guidelines and their asynchronicity can result in conflicting recommendations. For example, in the UK, four asthma guidelines could be followed (the GINA Report, British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines (BTS) and the NICE recommendations next to local guidelines)2,58,59, none of which are fully aligned. A review of three contemporaneous international guidelines updated in 2012 (The Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS), BTS and GINA) also revealed significant inconsistency arising from varying approaches to evidence interpretation and recommendation formulation60.

Globally, there is a move away from pure fee-for-service payments towards primary care payment schemes linked to performance, which recognise and reward good practice to improve quality and reduce costs61. These schemes combine quality standards and targets but still tend to be process driven, not outcome based. The evidence for the effectiveness of such schemes in general on improving quality of care is both inconclusive and inconsistent62.

The UK quality and outcomes framework (QOF), which includes asthma, is the world’s largest primary care payment for performance (P4p) scheme63. Evidence however shows that improved patient outcomes may not be sustained, cost reduction is unproven18 and leads to increased GP activity, but this does not necessarily correlate with improved individual patient benefit64,65. Furthermore, in Portugal, the recording of asthma and COPD prevalence as performance indicators in pay-for-performance contracts showed a modest but steady increase over time in physician’s diagnosis and ICPC-2 coding of these two conditions, but no direct patient benefits66.

Disease-specific schemes are usually aligned to clinical guidelines and some focus on prescribing. In Norway, under such a scheme, combination asthma medications were only reimbursed for patients diagnosed with asthma. As a result, asthma diagnosis significantly increased67.

The effect on health inequalities has also been studied. The results from UK QOF have shown that the gap between achievements from practices in the most deprived and least deprived areas narrowed68. Nevertheless, inequalities in morbidity and premature mortality persisted69,70. Additionally incentives can increase inequalities because those conditions that are ‘incentivised’ are afforded greater priority and resource allocation, to the detriment of those that are not71.

It would appear that simplistic fee-for-service schemes based purely on an activity—such as performing spirometry tests—which are not part of reimbursement of a more comprehensive assessment, have the potential to inadvertently lead to an increase in unnecessary tests. Pay-for-performance schemes have the potential to improve asthma care, but will be reliant on the specifics of the scheme and the quality indicators applied. They can be useful as part of a wider programme to raise quality and afford benefits over rewarding fee-for-service activity.

Appropriate practice organisation and systems focussing on the identification, diagnosis and treatment are pivotal for quality asthma care. There was compelling evidence to indicate that integrated, multi-faceted practice-based approaches for the management of patients improves outcomes and reduces the need for referral to secondary care22,25,72. Coordinated practice systems that combine several interventions such as decision support tools, flagging of electronic records, use of care pathways, staff training and structured approaches to patient education, if consistently implemented, afford the greatest benefits. Implementation of practice schemes is likely to be enhanced where there is dedicated clinical and administrative leadership.

Intuitively an accurate diagnosis should lead to better patient outcomes, although we found conflicting evidence that access to proper diagnosis has an impact on patient outcomes33,73. Nevertheless, an accurate diagnosis remains the fulcrum on which optimal asthma management depends. Indeed programmes in which an expanded medical team improved the quality of asthma care within the primary care setting (such as a diagnostic and management support organisation) show clear benefit on patient outcome32.

Spirometry combined with an assessment of reversibility has been set as gold standard for asthma diagnosis2. However, standards on quality of spirometry such as those set by the ERS and ATS are often not achieved74,75,76 and impose an unnecessarily high and potentially unachievable threshold in primary care73. Nevertheless, some studies have demonstrated that primary care office spirometry can meet the acceptability criteria77,78,79. Although such standards are laudable particularly in a specialist setting, their practicability in primary care, where patients commonly have mild–moderate, intermittent disease, is debatable. The latest ATS-ERS spirometry guidelines (published in October 2019) may address some of these issues.80 However, the use of spirometry in the diagnosis of asthma remains beyond reach in primary care around the world.

In many countries primary care physicians have limited or no access to tests of lung function or airway inflammation. The creation of diagnostic hubs in the community may open access to these tests32. A structured approach to diagnosis including applicability and feasibility for primary care is currently under development by an ERS taskforce; its outcome not available at the time of writing.

With rising clinical workloads, increasing clinical complexity and in many countries a shortage of trained primary care physicians, multi-professional teamworking is increasingly important.81,82 This is accentuated by the expectation for primary care to manage patients with chronic illness.

In many parts of the world, appropriately asthma-trained personnel, such as primary care nurses, are key to the delivery of high-quality asthma care. Dedicated nursing staff can offer continuity to patients, providing education and routine follow-up35. Evidence supports the concept that pharmacists working alone or in teams in collaboration with GPs are an accessible asset for the effective management of asthma and can positively influence asthma outcomes36.

Healthcare practitioner education is pivotal and the need for guideline-focused training in primary care is well established82. The literature seems to support this viewpoint but in many studies the effect on outcome has not been adequately considered, highlighting a need for more outcome-focussed research. Healthcare systems faced with the challenge of moving the care of people with long-term conditions such as asthma from established specialist services to primary care should consider implementing collaborative educational strategies44. Matrix-support collaborative care that includes training and support for primary care physicians/nurses from specialists, including joint consultations, case discussions and tailored education, has been shown to be well-accepted by primary care professionals and was associated with improved knowledge and reduced respiratory secondary care referrals44. A scoping exercise and literature review of the effectiveness of educational interventions in either changing health professional practice or in improving health outcomes was commissioned by The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG)83. The impact of education interventions on their own was inconclusive, although there was some evidence of effectiveness when they are combined with other quality improvement strategies or incentives83.

Asthma continues to be a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and there is need for a coordinated effort to improve care. A well-resourced primary care service is central to the provision of accessible and effective asthma care. An expert team identified the drivers that could enable improvements in both clinical management and patient outcomes, and a literature search showed that each of these individual drivers is supported by varying degrees of evidence. Objectively assessing the outcomes of such interventions is challenging because studies in this area are inherently complex, difficult to undertake and resource intensive, and so definitive research is seldom undertaken. In contrast single interventions studies are easier to conduct but frequently methodologically less robust and therefore tend to be inconclusive. Nevertheless, if substantial improvements in the management of asthma in primary care at a global level are to be achieved, combinations of interventions appear to be most effective. Well-supported holistic interventions involving the entire healthcare system and including the patient voice appear to provide the best outcomes.

Methods

Expert panel

An expert panel of 12 primary care global asthma experts—ten General Practitioners and two specialist nurses—was convened in Amsterdam. An initial teleconference between the panel preceded the meeting to gather ideas. The expert panel undertook a brainstorming exercise as part of a force-field analysis in order to reveal their ideas and experience regarding drivers of successful management of asthma in primary care84. A force-field analysis can be used to determine the forces (factors) that may prevent change from occurring and to identify those that cultivate change. During the brainstorming session, the experts were divided into facilitated groups to discuss the relative importance of the drivers and identify the factors which underpin each of them. Results were analysed thematically and circulated after the meeting for comment and agreement.

Literature review

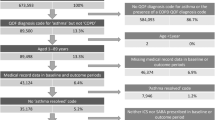

To identify whether evidence existed for the drivers and factors identified by the expert panel, literature was searched from PUBMED using the terms asthma and primary care in combination with other terms listed in Table 5. Proposed search terms were combined using Boolean operators. The initial search was limited to papers published in English over the last 10 years and studies in adults aged over 18 years old. The experts were also asked for additional papers and in addition, more articles were identified from the references from the selected papers. Papers identified were subsequently screened for eligibility by MF and TM (Fig. 1). A total of 171 were included in the summary table of which 50 papers were identified as having evidence for the factors identified by the panel.

Process by which papers identified by literature review were subsequently screened for eligibility and the different stages in this process. This highlights the number of articles that were selected at each stage of the process, as well as the number of articles excluded and the reasons for exclusion. n number of articles.

Data availability

Anonymised individual participant data from this study and its associated documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

References

Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2018. http://www.globalasthmanetwork.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf (2018).

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. www.ginasthma.com (2019).

Royal College of Physicians. Why Asthma Still Kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry Report (Royal College of Physicians, London, 2014).

D’Amato, G. et al. Asthma related deaths. Multidisc. Respir. Med. 11, 37 (2016).

Kirenga, B. J. et al. Rates of asthma exacerbations and mortality and associated factors in Uganda: a 2-year prospective cohort study. Thorax 73, 983–985 (2018).

Ebmeier, S. et al. Trends in international asthma mortality: analysis of data from the WHO Mortality Database from 46 countries (1993–2012). Lancet 390, 935–945 (2017).

World Health Organisation. Primary health care. Available from: https://www.who.int/primary-health/en/ (Accessed 30 May 2020).

The King’s Fund. Inverse-care law. Health Serv. J. 111, 37 (2001).

Aaron, S. D., Boulet, L. P., Reddel, H. K. & Gershon, A. S. Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198, 1012–1020 (2018).

Schneider, A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of spirometry in primary care. Bmc Pulm. Med. 9, 31 (2009).

Bosnic-Anticevich, S. Z. Asthma management in primary care: caring, sharing and working together. Eur. Respir. J. 47, 1043–1046 (2016).

Selroos, O. et al. National and regional asthma programmes in Europe. Eur. Respir. Rev. 24, 474–483 (2015).

Bateman, E. et al. Systems for the management of respiratory disease in primary care—an international series: South Africa. Prim. Care Respir. J. 18, 69–75 (2009).

Wattrus, C. et al. Using a mentorship model to localise the Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK): from South Africa to Brazil. Bmj Glob. Health 3, e001016 (2018).

Baldacci, S. et al. Prescriptive adherence to GINA guidelines and asthma control: an Italian cross-sectional study in general practice. Respir. Med. 146, 10–17 (2019).

Cloutier, M. M. et al. Clinician agreement, self-efficacy, and adherence with the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 6, 886–894 (2018).

Langdown, C. & Peckham, S. The use of financial incentives to help improve health outcomes: is the quality and outcomes framework for purpose? A systematic review. J. Public Health 36, 251–258 (2014).

Gillam, S. J., Siriwardena, A. N. & Steel, N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the quality and outcomes framework—a systematic review. Ann. Fam. Med. 10, 461–468 (2012).

Scott, A. et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD008451 (2011).

To, T. et al. Quality of asthma care under different primary care models in Canada: a population-based study. Bmc Fam. Pract. 16, 19 (2015).

Kirschner, K., Braspenning, J., Akkermans, R. P., Jacobs, J. E. & Grol, R. Assessment of a pay-for-performance program in primary care designed by target users. Fam. Pract. 30, 161–171 (2013).

Ryan, D., Murphy, A., Ställberg, B., Baxter, N. & Heaney, L. G. ‘SIMPLES’: a structured primary care approach to adults with difficult asthma. Prim. Care Respir. J. 22, 365–373 (2013).

Honkoop, P. J. et al. Adaptation of a difficult-to-manage asthma programme for implementation in the Dutch context: a modified e-Delphi. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 27, 1–9 (2017).

Smith, J. R. et al. The at-risk registers in severe asthma (ARRISA) study: a cluster-randomised controlled trial examining effectiveness and costs in primary care. Thorax 67, 1052–1060 (2012).

Smith, J. R. et al. At-risk registers integrated into primary care to stop asthma crises in the UK (ARRISA-UK): study protocol for a pragmatic, cluster randomised trial with nested health economic and process evaluations. Trials 19, 466 (2018).

Noble, M. J., Smith, J. R. & Windley, J. A controlled retrospective pilot study of an at-risk asthma register in primary care. Prim. Care Respir. J. 15, 116–124 (2006).

Fathima, M., Peiris, D., Naik-Panvelkar, P., Saini, B. & Armour, C. L. Effectiveness of computerized clinical decision support systems for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care: a systematic review. Bmc Pulm. Med. 14, 189 (2014).

Matui, P., Wyatt, J. C., Pinnock, H., Sheikh, A. & McLean, S. Computer decision support systems for asthma: a systematic review. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 24, 1–10 (2014).

Van der Meer, V. et al. Weekly self-monitoring and treatment adjustment benefit patients with partly controlled asthma; an analysis of the SMASHING study. Respir. Res. 11, 74 (2010).

Daines, L. et al. Clinical prediction models to support the diagnosis of asthma in primary care: a systemic review protocol. Npj Prim. Care Med. 28, 1–4 (2018).

Metting, E. I. et al. Asthma/COPD service in general practice. Study into feasibility and effectiveness. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 160, D281 (2016).

Lucas, A. E. M., Smeenk, F. J. W. M., Ben EEM van den Borne, B. E. E. M., Smeele, I. J. M. & van Schayck, O. C. P. Diagnostic assessments of spirometry and medical history data by respiratory specialists supporting primary care: are they reliable? Prim. Care Respir. J. 18, 177–184 (2009).

Price, D. et al. Using fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) to diagnose steroid-responsive disease and guide asthma management in routine care. Clin. Transl. Allergy 3, 37 (2013).

McAlister, F. A., Bakal, J. A., Green, L., Bahler, B. & Lewanczuk, R. The effect of provider affiliation with a primary care network on emergency department visits and hospital admissions. CMAJ 190, E276–E284 (2018).

Backer, V., Bornemann, M., Knudsen, D. & Ommen, H. Scheduled asthma management in general practice generally improve asthma control in those who attend. Respir. Med. 106, 635–641 (2012).

Berry, T. M., Prosser, T. R., Wilson, K. & Castro, M. Asthma friendly pharmacies: a model to improve communication and collaboration among pharmacists, patients, and healthcare providers. J. Urban Health 88, 113–125 (2011).

Armour, C. L. et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an evidence-based asthma service in Australian community pharmacies: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. J. Asthma 50, 302–309 (2013).

Gums, T. H. et al. Physician-pharmacist collaborative management of asthma in primary care. Pharmacotherapy 34, 1033–1042 (2014).

Kaferle, J. E. & Wimsatt, L. A. A team-based approach to providing asthma action plans. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 25, 247–249 (2012).

Woodcock, A. et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone furoate plus vilanterol on asthma control in clinical practice: an open-label, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 390, 2247–2255 (2017).

Bender, B. G. et al. The Colorado Asthma Toolkit Program: a practice coaching intervention from the High Plains Research Network. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 24, 240–248 (2011).

Colborn, K. L. et al. Colorado Asthma Toolkit implementation improves some process measures of asthma care. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 32, 37–49 (2019).

Gupta, S., Moosa, D., MacPherson, A., Allen, C. & Tamari, I. Effects of a 12-month multi-faceted mentoring intervention on knowledge, quality, and usage of spirometry in primary care: a before-and-after study. Bmc Pulm. Med. 16, 56 (2016).

Martins, S. M. et al. Implementation of ‘matrix support’ (collaborative care) to reduce asthma and COPD referrals and improve primary care management in Brazil: a pilot observational study. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 26, 16047 (2016).

Román-Rodríguez, M., Pardo, M. G., López, L. G., Ruiz, A. U. & van Boven, J. Enhancing the use of Asthma and COPD Assessment Tools in Balearic Primary Care (ACATIB): a region-wide cluster-controlled implementation trial. Npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 26, 16003 (2016).

Goeman, D. et al. Educational intervention for older people with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 93, 586–595 (2013).

Frost, J., Currie, M. J. & Cruickshank, M. An integrative review of enablement in primary health care. J. Prim. Care Community Health 6, 264–278 (2015).

Haahtela, T. et al. A 10-year asthma programme in Finland: major change for the better. Thorax 61, 663–670 (2006).

Kupczyk, M., Haahtela, T., Cruz, A. A. & Kuna, P. Reduction of asthma burden is possible through National Asthma Plans. Allergy 65, 415–419 (2010).

Chapman, K. R., Boulet, L. P., Rea, R. M. & Franssen, E. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur. Respir. J. 31, 320–325 (2008).

Price, C. et al. Large care gaps in primary care management of asthma: a longitudinal practice audit. Bmj Open 9, e022506 (2019).

Gagne, M. E. & Boulet, L. P. Implementation of asthma clinical practice guidelines in primary care: a cross-sectional study based on the Knowledge-to-Action Cycle. J. Asthma 55, 310–317 (2018).

Grol, R. & Grimshaw, J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 362, 1225–1230 (2003).

Alderson, L., Alderson, P. & Tan, T. Median life span of a cohort of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidelines was about 60 months. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 52–55 (2014).

Shekelle, P. et al. When should clinical guidelines be updated? BMJ 323, 155–157 (2001).

Clark, E., Donovan, E. P. & Schoettker, P. From outdated to updated, keeping clinical guidelines valid. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 18, 165–166 (2006).

Vernooij, R. et al. Reporting items for updated clinical guidelines: checklist for the reporting of updated guidelines (checkup). PLoS Med. 14, e1002207 (2017).

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). British guideline on the management of asthma. Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk (Edinburgh, SIGN, 2019).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Asthma: Diagnosis, Monitoring and Chronic Asthma Management. [NG80]. https://www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/ng80 (2017).

Gupta, S., Paolucci, E., Kaplan, A. & Boulet, L.-P. Contemporaneous international asthma guidelines present differing recommendations: an analysis. Can. Respir. J. 2016, 3085065 (2016).

Johnson, R. M., Johnson, T., Zimmerman, S. D., Marsh, G. M. & Garcia-Dominic, O. Outcomes of a seven practice pilot in a pay-for-performance (P4P)-based program in Pennsylvania. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2, 139–148 (2015).

Houle, S. K., McAlister, F. A., Jackevicius, C. A., Chuck, A. W. & Tsuyuki, R. T. Does performance-based remuneration for individual health care practitioners affect patient care? A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 157, 889–899 (2012).

Roland, M. & Guthrie, B. Quality and Outcomes Framework: what have we learnt? BMJ 354, i4060 (2016).

Gosden, T. et al. Impact of payment method on behaviour of primary care physicians: a systematic review. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 6, 44–55 (2001).

Christianson, J., Leatherman, S., Sutherland, K. Financial Incentives, Healthcare Providers and Quality Improvements: A Review of the Evidence (The Health Foundation, London, 2008).

Monteiro, B. R., Pisco, A. M., Candoso, F., Bastos, S. & Reis, M. Primary healthcare in Portugal: 10 years of contractualization of health services in the region of Lisbon. Cien Saude Colet. 22, 725–736 (2017).

Dalbak, L. G., Rognstad, S., Melbye, H. & Straand, J. Changed terms for drug payment influenced GPs’ diagnoses and prescribing practice for inhaled corticosteroids. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 19, 106–1010 (2013).

Doran, T. et al. Effect of financial incentives on inequalities in the delivery of primary clinical care in England: analysis of clinical activity indicators for the quality and outcomes framework. Lancet 372, 728–736 (2008).

Alshamsan, R. et al. Impact of pay for performance on inequalities in health care: systematic review. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 15, 178–184 (2010).

Kontopantelis, E. et al. Investigating the relationship between quality of primary care and premature mortality in England: a spatial whole-population study. BMJ 350, h904 (2015).

Roland, M. & Olsesen, F. Can pay for performance improve the quality of primary care. BMJ 354, i4058 (2016).

Gillett., K. et al. Managing complex respiratory patients. Bmj Open Resp. Res. 3, e000145 (2016).

Shaw, D. et al. Cross-sectional study of patterns of airway dysfunction. Prim. Care Respir. J. 21, 283–287 (2012).

Hegewald, M. J., Gallo, H. M. & Wilson, E. L. Accuracy and quality of spirometry in primary care offices. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 13, 2119–2124 (2016).

Schermer, T. R. J. et al. Accuracy and precision of desktop spirometers in general practices. Respiration 83, 344–352 (2012).

van de Hei, S. J. et al. Quality of spirometry in primary care: a focus on clinical use. Eur. Respir. J. 54(Suppl 63), OA252 (2019).

Bambra, G. et al. Office spirometry correlates with laboratory spirometry in patients with symptomatic asthma and COPD. Clin. Respir. J. 11, 805–811 (2017).

Licskai, C. J., Sands, T. W., Paolatto, L., Nicoletti, I. & Ferrone, M. Spirometry in primary care: an analysis of spirometry test quality in a regional primary care asthma program. Can. Respir. J. 19, 249–254 (2012).

Graham, B. L. et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 8, e70–e88 (2019).

Dall, T., Chakrabarti., R., Iacobucci, W., Hansari, A. & West, T. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2015 to 2030 (Association of American Medical Colleges, Washington, DC, USA, 2017).

Majeed, A. Primary care: a fading jewel in the NHS crown. Training sufficient and adequate general practitioners for universal health coverage in China. Lond. J. Prim. Care 7, 89–91 (2015).

Yawn, B. P., Rank, M. A., Cabana, M. D., Wollan, P. C. & Juhn, Y. J. Adherence to asthma guidelines in children, tweens and adults in primary care settings. A practice-based network assessment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 91, 411–421 (2016).

McDonnell, J. et al. Effecting change in primary care management of respiratory conditions: a global scoping exercise and literature review of educational interventions to inform the IPCRG’s E-Quality initiative. Prim. Care Respir. J. 21, 431–436 (2012).

Bauer, J., Duffy, G. & Westcott, R. Improvement Tools. The Quality Improvement Handbook 2nd edn, 109–148 (ASQ Quality Press, Milwaukee, WI, 2006).

Mehring, M. et al. Disease management programs for patients with asthma in Germany. A longitudinal population based study. Respir. Care 58, 1170–1177 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Expert Panel contributions of Tan Tze Lee (Singapore). Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, collating author comments, assembling tables/figures, grammatical editing, fact checking, and referencing) was provided by Diana Jones, Ph.D., of Cambrian Clinical Associates Ltd. (UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc. The expert panel meeting was funded by GlaxoSmithKline plc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the expert panel meeting. M.F. and T.v.d.M. were responsible for screening the papers identified in the literature search for suitability for inclusion in the article. All authors developed the manuscript and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.L. is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline plc., and holds stocks in GlaxoSmithKline plc. M.F. and T.v.d.M. are former employees of GlaxoSmithKline plc., and M.F. holds stocks in GlaxoSmithKline plc. I.T. reports advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline plc. and Novartis and a grant from GlaxoSmithKline Greece, outside the submitted work. J.K. reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Chiesi, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline plc., grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants from Mundipharma, grants from TEVA, outside the submitted work. A.C. reports a grant from AstraZeneca for an asthma study. C.C. reports grants from Pfizer China, outside of the submitted work. M.T. reports the following conflicts of interest: neither M.T. nor any member of his close family has any shares in pharmaceutical companies; receipt in the last 3 years of speaker’s honoraria for speaking at sponsored meetings or satellite symposia at conferences from GlaxoSmithKline plc. and Novartis, companies marketing respiratory and allergy products; receipt of honoraria for attending advisory panels with Boehringer Inglehiem, GlaxoSmithKline plc. and Novartis; membership of the BTS SIGN Asthma guideline steering group and the NICE Asthma Diagnosis and Monitoring guideline development group. P.K. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline plc., Chiesi, Menarini, Novartis, Klosterfrau, Bionorica, Willmar Schwabe and MSD, and other support (for a phase 3 investigator cough study) from MSD, all outside the submitted work. C.S. has no shares in any pharmaceutical companies, she has received consultant agreements and honoraria for presentations from several pharmaceutical companies that market inhaled medication including AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline plc., Napp Pharmaceuticals and Teva. J.C.d.S. reports personal fees and speaker’s honoraria from Boheringer Ingelheim, personal fees and speaker’s honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline plc., personal fees and speaker’s honoraria from AstraZeneca, personal fees and speaker’s honoraria from Mundipharma outside the submitted work. M.R.R. reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Chiesi, grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline plc., personal fees from Menarini, personal fees from Mundipharma, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Bial, outside the submitted work. E.M.K. received honoraria for attending advisory board meeting from GlaxoSmithKline plc., Boehringer Inglehiem and grant from Novartis outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fletcher, M.J., Tsiligianni, I., Kocks, J.W.H. et al. Improving primary care management of asthma: do we know what really works?. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 29 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-0184-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-0184-0

This article is cited by

-

Over-prescription of short-acting β2-agonists remains a serious health concern in Kenya: results from the SABINA III study

BMC Primary Care (2023)

-

Healthcare resources, organisational support and practice in asthma in six public health clinics in Malaysia

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2023)

-

Qualitative study on perceptions of use of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FeNO) in asthma reviews

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2022)

-

Short-acting β2-agonist prescription patterns for asthma management in the SABINA III primary care cohort

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2022)