Abstract

The pathology of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by α-synuclein aggregation, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra with collateral striatal dopamine signaling deficiency. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been linked independently to each of these facets of PD pathology. The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3, upregulated in microglia by α-synuclein and facilitating potassium efflux, has also been identified as a modulator of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in models of PD. Evidence increasingly suggests that microglial Kv1.3 is mechanistically coupled with NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which is contingent on potassium efflux. Potassium conductance also influences dopamine release from midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Dopamine, in turn, has been shown to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. In this review, we provide a literature framework for a hypothesis in which Kv1.3 activity-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, evoked by stimuli such as α-synuclein, could lead to microglia utilizing dopamine from adjacent dopaminergic neurons to counteract this process and fend off an activated state. If this is the case, a sufficient dopamine supply would ensure that microglia remain under control, but as dopamine is gradually siphoned from the neurons by microglial demand, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and Kv1.3 activity would progressively intensify to promote each of the three major facets of PD pathology: α-synuclein aggregation, microglia-mediated neuroinflammation, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Risk factors overlapping to varying degrees to render brain regions susceptible to such a mechanism would include a high density of microglia, an initially sufficient supply of dopamine, and poor insulation of the dopaminergic neurons by myelin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background: Parkinson’s disease pathology and the microglial NLRP3 inflammasome

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most prevalent movement disorder and the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease, only Alzheimer’s disease being more common1,2,3,4. Though familial PD, involving mutations in genes for disease-relevant proteins including LRRK2, PARK7, PINK1, DJ1, PRKN, and SNCA, accounts for a small proportion of cases, approximately 90% of PD cases are sporadic, with no readily identified catalyst for pathology1,2,5,6,7,8,9. External factors such as elevated levels of heavy metals like manganese or copper10,11 or exposure to pesticides like the electron transport chain Complex I inhibitor rotenone or paraquat12 have been implicated in the etiology of PD13, presumably exerting their effects by interfering with mitochondrial function and generating increased levels of reactive oxygen species, but age is the most important risk factor for the disease, which occurs in about 1–2% of the over-60 population1,14,15,16,17. As the population ages, more time and cost will be invested into treatments for PD patients, and the pressing need for improved interventions and etiological insight into both the familial and sporadic forms of the disease is evident18.

The pathology of PD typically displays three cardinal features. One is the accumulation of the protein α-synuclein, leading to the formation of intraneuronal inclusions known as Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites (LNs) in areas of neurodegeneration1,19,20,21,22. Another key characteristic of PD is neuroinflammation, hallmarked by the presence of activated microglia which assemble around degenerating dopaminergic neurons23,24. This dopaminergic neurodegeneration represents the third major facet of PD pathology, taking place most prominently in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) region of the midbrain and leading to impaired striatal dopamine signaling25,26,27,28. The ramifications of inadequate dopamine signaling in the basal ganglia are clear in PD, as motor symptoms such as akinesia and tremor develop as a result29.

α-Synuclein

α-Synuclein (α-syn) is an ~14 kDa protein with its most prevalent expression in brain tissue. It is primarily expressed by neurons, where it is localized to the presynaptic terminal and the nucleus (hence its name synuclein22,30), and it is thought to be involved under baseline conditions in the transport of intracellular vesicles31,32,33. α-Syn contains seven repeats of a synuclein family-specific amino acid sequence containing the consensus residues KTKEGV22,34. These repeats have been shown to be involved in normal tetramerization of the α-syn peptide, and alterations in the consensus sequence are associated with increased neurotoxicity34. α-Syn is an intrinsically disordered protein35 with a propensity to misfold and aggregate into cross-β-sheet-rich fibrils and oligomers9,15,22,36, especially upon irreversible truncation at its C-terminal6,37. The C-terminal truncated α-syn is more likely to aggregate than full-length α-syn32, and it is pervasive in PD-associated LBs but is typically not found in soluble form37. While PD is the most frequently encountered synucleinopathy, α-syn aggregation pathology also occurs in other diseases such as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and multiple system atrophy (MSA)22,32,38,39,40,41,42.

Soluble α-syn is known to be secreted from neurons into the extracellular space, and microglia have been suggested to be the primary cell type responsible for its clearance43. α-Syn has been shown to activate microglia after phagocytosis, contributing specifically to dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a murine primary neural-glia coculture model of parkinsonism21. In fact, α-syn has been reported to activate microglia tenfold more than Alzheimer’s disease-associated Aβ21. α-Syn-activated microglia were shown to be critical for dopaminergic neurodegeneration in a rat primary cell PD model, and phagocytosis of the α-syn by microglia was imperative to this process21.

PD-associated neuroinflammation is typified by the presence of activated microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, which assemble around degenerating neurons23,24,44. Microglia-mediated cross-talk with neurons plays a major role in the pathology of PD45. The SNpc is, notably, the brain region in which the density of microglia is the highest21,23,24,46,47,48. A major role in the perpetuation of PD-associated neuroinflammation is played by the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β), which is secreted in the central nervous system (CNS) primarily by microglia acting as immune effectors37,49,50,51. While elevated levels of other cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 are also associated with microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases including PD, IL-1β is increased in the brain and CSF of both PD and AD patients51 and in the dopaminergic striatal tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of PD patients51,52,53,54. These observations suggest a potential mechanistic link between IL-1β production, particularly by microglia, and PD pathology in vivo.

The NLRP3 inflammasome

The canonical mechanism for IL-1β release from microglia and peripheral myeloid cells involves activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome49,55,56, which is a multimolecular scaffold whose primary function is to amplify and broadcast pro-inflammatory signals from one cell to another by driving the secretion of both IL-1β and, to a lesser extent, IL-1857,58,59. Highly expressed by microglia, the three traditionally accepted component proteins of the NLRP3 inflammasome are: (1) the intracellular pattern recognition receptor NACHT domain-, leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), which oligomerizes upon efflux of potassium (K+) from the cell to recruit (2) the small adapter protein known as apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD), or ASC, which further oligomerizes to recruit (3) the cysteine-aspartate protease-1 (caspase-1)20,56,57,60. Caspase-1’s recruitment to the inflammasome scaffold results in an increase of its local concentration, leading to its proximity-induced auto-activation, and caspase-1 is then released from the complex in its active p33/p10 form both to process IL-1β for secretion and downstream signaling and to intrinsically cue the cessation of inflammasome activation57,61.

Because IL-1b is such a potent inflammatory signal, its production by the NLRP3 inflammasome is regulated on multiple levels62. Upon their initial expression, IL-1β and IL-18 are both “leaderless” cytokines, lacking the hydrophobic targeting sequence for exocytosis that other cytokines like IL-6 possess and thus requiring further processing by cleavage for activation and secretion from the cell63. IL-1β is initially produced in its inactive zymogen form (pro-IL-1β), and NLRP3 inflammasome activation must take place to facilitate IL-1β maturation via caspase-mediated cleavage. NLRP3 inflammasome activation requires two separate, sequential signals for scaffold assembly and the subsequent cleavage of pro- to active IL-1β by caspase-1. The first signal, known as priming, typically involves ligand binding to cell surface receptors such as IL-1 receptors, tissue necrosis factor (TNF) receptors, or Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and thus, the molecular natures of priming signals are diverse. Priming precipitates the translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus of the transcription factor NF-κB, which, among other functions, elicits the upregulation of both NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β59. The second signal, known as activation, also varies mechanistically, but increasing evidence suggests that differential activation signals converge on the efflux of potassium ions (K+) from the cell as a consensus signal to trigger the oligomerization of NLRP3 and the ensuing recruitment of ASC and caspase-1 to form the rest of the inflammasome scaffold to process IL-1β64,65,66.

α-Syn aggregates have been shown in vitro to act as an NLRP3 inflammasome inducer in various human cell types: primary monocytes7, in THP-1-derived, macrophage-like cells67,68, and in primary microglia67, all leading to the processing and secretion of mature IL-1β into the culture supernatant. Evidence of in vivo activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome has been detected in association with α-syn in the affected brain tissue of PD patients; notably, caspase-1 is present alongside α-syn in Lewy bodies with a spatially ordered distribution37. This spatially ordered distribution may be a result of the caspase’s binding pattern on the inflammasome scaffold and indicative of the inflammasome’s role in Lewy body formation. It has been suggested that NLRP3 inflammasome initiation specifically by α-syn plays a role in the emergence and facilitation of progressive PD pathology7,68.

A biochemical relationship between canonically activated caspase-1 and α-syn has been demonstrated in which the active caspase cleaves α-syn at Asp121 to a truncated form (α-syn 1–121) that is more prone to aggregation and is present in Lewy bodies in vivo37. In the same study, caspase-1 was detected in association with α-syn in Lewy bodies in brain tissue from PD patients, leading the authors to hypothesize that α-syn aggregation and Lewy body formation in neurons might be promoted over time by caspase-1 activity. This relationship between caspase-1 activity and α-syn may account for our observation that caspase-1, though it was recruited to the inflammasome scaffold and thus presumably activated, was not necessary for IL-1β processing by primary human microglia in response to α-syn activation67. If caspase-1 is diverted to α-syn processing in α-syn-activated human microglia, the task of IL-1β processing in response to NLRP3 inflammasome activation would then likely fall to other caspases or proteases.

Alternative caspase activation mechanisms

Indeed, apart from the caspase-1-dependent canonical inflammasome pathway, an alternative mechanism for NLRP3 inflammasome activation has been described for monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages of humans, nonhuman primates, and mice. Known as noncanonical inflammasome activation, this mechanism occurs in response to the intracellular uptake of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) after an exposure time of 16 h or more69,70,71,72,73. The internalized LPS binds directly to the CARDs of caspases other than caspase-1, which then serve as cytosolic rather than surface LPS receptors to induce IL-1β secretion74. The caspases responsible for this process belong to the caspase-1 subfamily: caspases-4 and -5 in humans and nonhuman primates69,70,72,73,75 and caspase-11, the murine homolog of caspases-4 and -5, in mice74,76,77,78. Activation of noncanonical inflammasomes, particularly by triggers other than LPS, has not yet been fully characterized, and which caspases in particular are involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary human microglia, especially in neurodegenerative disease-related conditions, remains uncertain. Unpublished work from our group suggests that caspases-4 and -5, along with caspase-8, play a role in α-syn-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary human microglia (Pike et al., manuscript in preparation).

Interestingly, both caspases-1 and -8 regulate the protein parkin79. Parkin, encoded by the genes PARK2 and PARK6, is an E3 ligase that ubiquitinates NLRP3 among other proteins80. Loss-of-function mutations of parkin are associated with familial PD, and both microglia from PARK2 knockout in vivo models and peripheral macrophages from patients with PARK2 mutations displayed enhanced IL-1β and IL-18 output80. These observations link inflammasome regulation and specific caspases to inherited as well as sporadic forms of PD.

While another of the major facets of PD, dopaminergic neurodegeneration, has long been known to require microglia in several in vivo and in vitro models21,45,81,82, the focus on the mechanistic role of microglia in this process has narrowed further to include NLRP3 inflammasome activation in particular. Inhibition of NLRP3 by MCC950 (CRID3) or knockdown of NLRP3 or caspase-1 expression spares dopaminergic neurons from microglia-mediated degeneration14,83,84,85. The specific mechanistic nature of the dependence of dopaminergic neurodegeneration on the inflammasome is not yet known, though the links between the NLRP3 inflammasome and PD pathology are becoming increasingly clear. NLRP3 inflammasome components have been observed in the pathological brain tissue of in vivo parkinsonism mouse models as well as in human PD brain, produced by activated microglia in particular14. NLRP3 and ASC have been shown to be upregulated in substantia nigra microglia of PD patients and have also been detected in the striatal microglia of mouse models of parkinsonism14, implicating the NLRP3 inflammasome as a key agent in PD pathology. Degeneration is largely relegated to the dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc, and the mechanistic reason for their vulnerability relative to the dopaminergic neurons of the neighboring ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a subject of ongoing investigation86,87.

Microglia and PD pathology: potassium efflux

K+ efflux is widely accepted as a consensus step for the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome scaffold64,65,66,88,89,90,91,92. This dependence has been attributed to the action of the protein NEK7 (never-in-mitosis/NIMA-related kinase 7), which is recruited to the NLRP3 inflammasome complex and is crucial for its activation downstream of K+ efflux66,92,93. Originally identified as an inflammasome regulator via CRISPR screening by Schmid-Burgk et al.65, NEK7 is an intracellular K+ sensor, which interacts with NLRP3 to signal for oligomerization of the latter upon K+ efflux from the cell64. NEK7 only operates outside of the mitosis portion of the cell cycle, meaning that the cells that are susceptible to inflammasome activation are limited to those in interphase66, and thus not all cells in a stimulated culture display NLRP3 inflammasome activity simultaneously. Elevated extracellular K+ levels in the range of 50–130 mM have been reported to inhibit various mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, both canonical and noncanonical91,94 (Pike et al., in press), by eliminating the electrochemical gradient that drives K+ efflux leading to NEK7 signaling.

While not unique to inflammasome activation93, K+ efflux can be induced in a number of ways to provoke inflammasome activation. One commonly employed mechanism to do so artificially is the use of the bacterial pore-forming toxin nigericin, which is a K+/H+ antiporter that transports protons into the cell, decreasing intracellular pH, in exchange for departing K+ ions95. In the absence of the introduction of a foreign channel into the plasma membrane, K+ efflux can also occur via endogenously expressed K+ channels. Many such channels exist, and these are categorized into various families and subfamilies with different means of activation96. The two-pore domain K+ channel TWIK2 has been implicated specifically in K+ efflux leading to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in mouse lung- and bone marrow-derived macrophages in response to ATP and LPS97. TWIK2, however, has been reported to be predominantly expressed in the periphery rather than in the CNS98, making it unlikely to participate in microglial inflammasome activation.

Kv1.3

In contrast to TWIK2, the delayed rectifier voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.3, coded for by the intronless gene KCNA3, is widely expressed in the CNS. Kv1.3 is a member of the Shaker family of K+ channels99 with four subunits, each containing six transmembrane segments and a voltage sensor that opens upon detection of membrane depolarization to allow for K+ efflux100. While it is one among many Kv1 channels, which are also expressed in dopaminergic neurons101, evidence increasingly points to a critical, specific role for microglial Kv1.3 in neuroinflammation, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and neurodegeneration. Microglial expression of Kv1.3 is low at baseline in comparison to neuronal expression but increases significantly upon microglial activation with LPS in rodents102,103,104. Microglial activation with LPS results in increased K+ conductance that is mediated by Kv1.3105. The activity of microglial Kv1.3 upon LPS treatment has been associated with neuroinflammation and microglia-mediated neurotoxicity in rats, being required for neurodegeneration104. Microglial Kv1.3 has been found to be required for neuroinflammation in LPS-activated microglia in an in vivo mouse model, where Kv1.3 knockout prevented microglial activation and IL-1β production106. Kv1.3 was demonstrated to be upregulated in post-mortem brains of patients with PD as well as in the MPTP, α-synPFF, and MitoPark in vivo parkinsonism models100. Kv1.3 was significantly upregulated both in the MMC mouse microglia cell line and in vivo in response to treatment with aggregated α-syn, and this upregulation was both linked to increased channel activity and largely reversible in the presence of the specific Kv1.3 blocker PAP-1100. Crucially, this Kv1.3 upregulation played a significant role in neuroinflammation-mediated neurodegeneration in the MitoPark and MPTP in vivo parkinsonism models that were ameliorated upon PAP-1 administration100. These observations link Kv1.3 with the major facets of PD pathology.

Since the MPTP, α-synPFF, and MitoPark parkinsonism models as well as LPS treatment of microglia are all associated with both enhanced Kv1.3 expression100,102,103,104,105 and augmented NLRP3 inflammasome activation14,67,83, the question arises as to whether there may be a direct link between Kv1.3 activity and inflammasome activation. Indeed, Kv1.3 inhibition with PAP-1 was shown specifically to decrease NLRP3 expression and IL-1β production in mouse microglia to control CNS inflammation in ischemia/reperfusion models107, and Kv1.3 has been linked to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in T lymphocytes as well108. Kv1.3 K+ currents required caspase-8 activity in Jurkat T lymphocytes109, although inflammasome involvement was not directly examined in this study. PAP-1 treatment diminished NLRP3 expression in MMC mouse microglia cells activated with aggregated α-syn100. Moreover, preliminary work from our group suggests that Kv1.3 blockade inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary human microglia, which we previously found to be K+ efflux-dependent (Pike et al., in press)67. While microglial production of other, non-inflammasome-related cytokines is also attenuated by Kv1.3 blockade106, we suggest that the K+ efflux aspect of NLRP3 inflammasome activation may account in part for the deleterious role of microglial Kv1.3 in PD-associated neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation.

Microglia and PD pathology: dopamine

The state of striatal dopamine release is of considerable importance in the diagnosis and research of PD. The deficiency of dopamine signaling in this brain region due to the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc, which project into the striatum, is responsible for the characteristic motor symptoms observed as the disease progresses110. In a clinical setting, imaging assessments of striatal dopamine functionality can be used to determine the stage of dopaminergic decline, for example by 18F-DOPA PET111 or DaTscan112, but early detection is difficult because striatal dopamine input has typically already diminished by 70–80% by the time motor symptoms begin to manifest29,113,114,115,116. Dopamine release takes place in a diffusion-based, three-dimensional volume transmission manner to act over a relatively broad distance of several micrometers117. It is salient that while dopamine release from midbrain dopaminergic neurons occurs axonally in the striatum, it also occurs somatodendritically in a localized fashion in the substantia nigra (SN) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA)86,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124. Dopamine release in the midbrain is influenced by K+ flux; somatodendritic dopamine release is dependent on action potentials and various K+ channels120,121, and striatal dopamine release was shown to be regulated by neuronal Kv1 channels including Kv1.3101.

Anti-inflammatory effects of dopamine upon its binding to DRD1 and/or DRD2 receptors on microglia have been reported85,125. Dopamine was shown to dampen inflammation in primary rat microglia by regulating the pro-inflammatory renin-angiotensin system through DRD1 and DRD2 signaling125. Dopamine also attenuated neuroinflammation in both primary mouse microglia and in the MPTP parkinsonism model in vivo, specifically by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β secretion induced by various canonical stimuli through DRD1-mediated signaling for the E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitination and autophagic degradation of NLRP3 protein85. The SNpc and striatal microglia of both PD and normal control patients express dopamine receptors DRD1-DRD4 (but not DRD5) in situ, as do primary human microglia cultured in vitro after isolation47. Previous work by our group documented the ability of dopamine to block not only canonical and noncanonical but also α-syn-induced NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion from isolated primary human microglia, and DRD1 agonism in both primary human microglia and in vivo in the SYN120 transgenic parkinsonism model decreased microglial inflammasome activation (Pike et al., in press). As a whole, these observations point to an inhibitory role for dopamine on PD-relevant microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation.

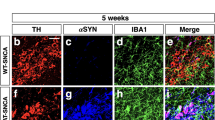

In an in vitro coculture model with neuronal cells, isolated primary human microglia showed a tendency that was augmented upon activation of the microglia with LPS to cluster preferentially around tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing neuronal cells as compared to non-dopaminergic phenotypes47. The LPS-activated microglia also engaged in a strong chemotactic response to dopamine, and the authors suggested that the effects of dopamine on activated human microglia may explain the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to microglia-mediated degradation in PD47. These authors interpreted their findings as an indication of a role for dopamine in the facilitation of dopaminergic neurodegeneration by activated microglia. However, another interpretation is possible in light of the more recently observed effects of dopamine on inflammasome activation: that the selective attraction of α-syn- or otherwise-activated microglia to dopamine-producing neurons could be accounted for by the ability of dopamine to inhibit the inflammasome as a means of maintaining homeostasis by mitigating neuroinflammation.

Discussion: hypothesis for the convergence of NLRP3 inflammasome, potassium, and dopamine mechanisms in PD pathology

Each of the three key characteristics of PD, namely α-syn pathology, neuroinflammation, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration, has been linked independently to the NLRP3 inflammasome as well as to Kv1.3 channel activity. Mechanistic connections between the NLRP3 inflammasome and Kv1.3 are becoming increasingly clear, and we suggest that K+ efflux leading to microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation associated with PD pathology may proceed through Kv1.3. Dopamine release from dopaminergic neurons is influenced by K+ flux, and dopamine has been shown to be able to block NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary human and mouse microglia.

We propose a hypothesis for PD pathology (first described in Pike et al., in press and illustrated in Fig. 1) in which sustained activation of microglia in the SNpc by α-syn or other known stimuli induces K+ efflux through Kv1.3, with or without the help of other channels, to initiate NLRP3 inflammasome activation with resultant IL-1β secretion. The IL-1β would potentiate neuroinflammation while the K+ efflux from the microglia could present localized fluctuations in extracellular K+ concentrations, provoking somatodendritic dopamine release from proximal dopaminergic neurons. (Alternatively, dopamine release may occur nonspecifically as microglia-mediated neurodegeneration, fueled as previously demonstrated by both the NLRP3 inflammasome and microglial Kv1.3 activity, progresses.) Released dopamine could then bind to its receptors on adjacent microglial surfaces. Each of these processes could be enhanced by dopamine-mediated chemotactic recruitment of additional inflammasome-activated microglia. The dopamine would then be able to provide a negative feedback signal for inflammasome activation and neuroinflammation, but gradually deplete the neuronal dopamine supply in the process. Functional dopamine signaling in the SNpc and striatum could be preserved in the presence of ample dopamine but would become increasingly impaired as neuronal stores are exhausted by microglial demand. If the dopamine countersignal thus fades, the extent of microglial inflammasome activation could overtake that of dopamine-mediated inhibition, escaping regulation to a point of imbalance and a net amplification of NLRP3 inflammasome- and Kv1.3-associated PD pathology, with the dopaminergic neurons becoming overwhelmed and succumbing to the microglia. In this context, being equipped with a dopamine supply would be protective for the neurons, but being a dopaminergic neuron would be a liability if the dopamine supply is or becomes inadequate.

α-Syn binds to surface receptors and is taken up by microglia, leading to Kv1.3 (possibly assisted by other K+ channels) -mediated K+ efflux signaling for the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1. The efflux of K+ could provoke K+ channel-mediated or toxicity-induced release of dopamine from proximal dopaminergic neurons. Dopamine could then bind to its receptors on microglia to curb activation of the inflammasome. Sufficient DA in the system would keep this interaction under control, but if DA is depleted over time by the microglia, the imbalance could allow for the progression of inflammasome-associated α-syn aggregation, neuroinflammation, and neurotoxicity, and thus PD pathology.

If a mechanism such as that which we propose should prove to participate in PD pathology, it could help to explain the largely selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons in PD, and particularly those in the SNpc in comparison to those in the VTA or other brain regions87,114. Dopaminergic neurons are characterized by their expression levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine114,126. The SNpc and VTA areas of the midbrain are dopamine-rich, containing the two largest populations of TH+ neurons out of nine dopaminergic groups in the mammalian brain114. The substantial density of microglia in the SN, the highest in the brain24,46,48 at 12% of its cell population127, is threefold that of the VTA128, and this likely renders its neurons more susceptible to microglia-mediated attack than neurons in other locations including the VTA once the microglia are activated. There are other brain regions that also contain a relatively dense population of microglia, like the hippocampus;127 however, neurons in these regions lack their own dopamine stores, instead of receiving dopamine input from the VTA and the locus coeruleus (LC)129,130. Dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the VTA and LC can be observed in PD, but neuronal loss occurs to a lesser extent in these regions than in the SNpc and is not specific to PD, being apparent in other diseases like Alzheimer’s (AD) as well87,114. AD patients display upregulated Kv1.3 in the frontal cortex131 as well as increased caspase-1 activation in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, suggesting increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation132. However, without a dopamine supply comparable to that of the SNpc, there is less dopamine available there to play inhibitory and chemotactic roles in the context of the hypothesis we propose. We suggest that the interplay between Kv1.3, dopamine, and inflammasome activation that we propose takes place to drive pathology to whatever extent these three factors are present and functional in a given brain region, and thus can vary in intensity by location.

In addition to their microglia population and their ready dopamine supply, the dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc are postulated to have axons that are long, highly branched, and poorly myelinated87,133,134. The extensive branching places a high metabolic demand on SNpc dopaminergic neurons in comparison to neurons in other areas87. Insufficient insulation by myelin could confer vulnerability to small, local fluctuations in K+ flux and electrical signaling that might be largely avoided in other, better-insulated areas. While spatial buffering of K+ by local astrocytes would theoretically help to avoid this issue, astrocytes of the ventral midbrain, including in the SN, have low membrane resistance and low baseline levels of Kir-mediated currents relative to astrocytes of the hippocampus or cortex135. This finding has been suggested to indicate a comparatively diminished K+ buffering function of astrocytes in the ventral midbrain that could have an electrical impact on the regulation of burst firing of the dopaminergic neurons they serve135. If this is the case, these neurons might be rendered more susceptible than those in other regions of the brain to the stress of superfluous extracellular K+ generated locally by microglial Kv1.3 activity.

In summary, we suggest three main factors for brain region susceptibility to PD pathology, mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome, K+, and dopamine mechanism-based interaction that we propose in our hypothesis, which overlaps in the SNpc to a greater extent than in the VTA or other brain regions: (1) high microglia density with attendant NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activity, (2) a ready dopamine supply, stored in dopaminergic neurons, and (3) poor myelination of these neurons, leaving them more vulnerable than other neuronal populations to swings in ion flux and electrical signaling. Variability across brain regions in transcriptional profiles of microglia46 and differential distribution of α-syn expression and isoforms/conformations are also very important factors in PD development. However, examining these intact from the human brain proves very difficult because microglia are so plastic and their transcriptional profiles so responsive to their surroundings136 and because much of the conformational structure of α-syn is lost upon water dissipation after death and upon treatment with fixatives such as paraffin, which would disrupt lipid-soluble conformations137. While α-syn pathology undoubtedly plays an important role in PD progression and is associated mechanistically with inflammasome and caspase-1 activities14,37 as well as microglia-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration21, Lewy body/Lewy neurite pathology per se does not always correlate with neurodegeneration or loss of motor function87; moreover, it is not unique to PD, as other synucleinopathies like DLB and MSA also display α-syn pathology but in brain regions other than the SNpc45,138.

Conclusions

In this review, we provide the framework for a hypothesis in which microglial NLRP3 inflammasome, K+ flux, and dopamine response mechanisms interact to maintain homeostasis between microglia and neurons by modulating microglial activation through dopamine-mediated negative feedback on the inflammasome. If this synergy is disrupted such that the dopamine supply is depleted and NLRP3 inflammasome activation intensifies, the three major facets of PD pathology (α-syn accumulation, neuroinflammation, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration) would be augmented as a result of weakened microglial regulation. We propose that high microglia density, local dopamine stores, and inadequate axonal myelination serve as key determinants that confer risk for pathology mediated by the mechanism that we put forth, and that these factors overlap to a greater extent in the SNpc than in other brain regions like the VTA or LC, where the confluence would be less, helping to explain the predominant targeting of this area in PD. While the literature evidence provided here lays the groundwork for this idea, more work remains to be done to provide further support. Experiments designed to explore the relationships between the inflammasome, its specific mode of K+ efflux, and the effects of dopamine on these must be performed.

If a mechanism such as that which we propose is operational in PD pathology, it could shed more light on the etiology of the disease, and furthermore, open the door to treatment options alternative to or in conjunction with L-DOPA therapy to potentially lessen the need for long-term l-DOPA administration with its ancillary risks. While l-DOPA treatment has long been the gold standard for PD therapy139,140, its long-term use is associated with the risk of l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia141. For this reason, l-DOPA treatment for most patients does not occur until long after symptoms have become evident enough to lead to a PD diagnosis. By the time motor symptoms begin to manifest, as mentioned above, striatal dopamine input has typically already diminished by 70–80%29,114,115. Even if l-DOPA administration were begun immediately upon diagnosis, the process we describe in our hypothesis likely would have been happening for a very long time prior. Because of the extent of neurodegeneration at that point, other factors outside of those involved in the hypothesized mechanism would be contributing to further degradation of neurons in the area (e.g., reactive oxygen species, ATP released from dying neurons, etc.), and l-DOPA administration would likely not be able to halt these more general mechanisms. Thus, the key to stopping the pathological feedback mechanism we propose would lie not in late-stage dopamine replacement therapy, but in preventing the initial loss of dopamine leading to neurodegeneration by controlling the activities of Kv1.3 and the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Sarkar et al.100 showed initial evidence that Kv1.3 is not only elevated in microglia but also in peripheral B cell lymphocytes from both early- and late-stage PD patients in comparison to those from healthy controls. This led them to the suggestion that Kv1.3 expression in peripheral lymphocytes could serve as a potential biomarker for PD, though this remains to be confirmed with studies involving larger sample sizes. If this proves to be the case, we suggest that early screening for prodromal PD could involve an initial plasma evaluation for elevated B cell lymphocyte Kv1.3 expression which could be followed up with 18F-DOPA PET imaging to examine dopamine signaling functionality. If both of these tests are abnormal, and cancer is ruled out through analysis of the original blood sample or other appropriate methods (as Kv1.3 expression can be associated with some cancers142 and abnormal 18F-DOPA PET results can be indicative of neuroendocrine tumors143), the combination could be indicative of prodromal PD and intervention could be possible prior to large scale neurodegeneration and the development of motor symptoms. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors are already being tested for their efficacy in slowing/preventing PD pathology, as are Kv1.3 blockers. If such treatment strategies are effective and could be administered prior to significant neurodegeneration, they could prove to be truly disease-modifying therapies for PD.

Moreover, a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified 90 genetic risk factors for PD144, several of which may be pertinent to the mechanism we hypothesize. Those of particular interest in this context include the FYN gene encoding Fyn kinase, which has been shown to regulate microglial α-syn uptake and NLRP3 inflammasome activation145 in addition to modulating Kv1.3 expression100. Among many other genes with low penetrance relative to previously identified causative, higher-penetrance PD genes such as SNCA, PARK2, and LRRK2, this GWAS study also identified as PD risk factors NFKB2, encoding a subunit of the Nf-κB complex, SCAF11, encoding a caspase, and KCNS3 and KCNIP3, both encoding voltage-gated potassium channel subunits (Kv9.3 and calsenilin). While the NLRP3 and KCNA3 genes, encoding NLRP3 and Kv1.3, respectively, were not identified specifically in the study, it is possible that each as an independent genetic risk factor may be neutralized by compensatory mechanisms. However, if FYN upstream is affected such that both NLRP3 and Kv1.3 signaling are enhanced simultaneously, particularly together with Nf-κB, given its known role in upregulating NLRP3 and Kv1.3 expression, and other potassium channels, these genes if present in some combination may form a polygenic risk panel for PD pathology proceeding according to our hypothesis that could be identified upon genetic screening.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Glass, C. K., Saijo, K., Winner, B., Marchetto, M. C. & Gage, F. H. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell 140, 918–34 (2010).

Paul, K. C., Schulz, J., Bronstein, J. M., Lill, C. M. & Ritz, B. R. Association of polygenic risk score with cognitive decline and motor progression in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 75, 360–6 (2018).

Jiang, P. & Dickson, D. W. Parkinson’s disease: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 13–32 (2018).

Nussbaum, R. L. & Ellis, C. E. Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1356–64 (2003).

Tran, J., Anastacio, H. & Bardy, C. Genetic predispositions of Parkinson’s disease revealed in patient-derived brain cells. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 6, 8 (2020).

Faustini, G. et al. Mitochondria and alpha-Synuclein: friends or foes in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease? Genes 8, 377 (2017).

Codolo, G. et al. Triggering of inflammasome by aggregated alpha-synuclein, an inflammatory response in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE 8, e55375 (2013).

Gasser, T. Molecular pathogenesis of Parkinson disease: insights from genetic studies. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 11, e22 (2009).

Spillantini, M. G. et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–40 (1997).

Kulshreshtha, D., Ganguly, J. & Jog, M. Manganese and movement disorders: a review. J. Mov. Disord. 14, 93–102 (2021).

Bisaglia, M. & Bubacco, L. Copper ions and Parkinson’s disease: why is homeostasis so relevant? Biomolecules 10, 195 (2020).

Kanthasamy, A., Jin, H., Charli, A., Vellareddy, A. & Kanthasamy, A. Environmental neurotoxicant-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration: a potential link to impaired neuroinflammatory mechanisms. Pharm. Ther. 197, 61–82 (2019).

Kieburtz, K. & Wunderle, K. B. Parkinson’s disease: evidence for environmental risk factors. Mov. Disord. 28, 8–13 (2013).

Gordon, R. et al. Inflammasome inhibition prevents alpha-synuclein pathology and dopaminergic neurodegeneration in mice. Sci Transl Med. 10, eaah4066 (2018).

Brundin, P. & Melki, R. Prying into the prion hypothesis for Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 37, 9808–18. (2017).

Song, J., Kim, B. C., Nguyen, D. T., Samidurai, M. & Choi, S. M. Levodopa (L-DOPA) attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress response and cell death signaling through DRD2 in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells under alpha-synuclein-induced toxicity. Neuroscience 358, 336–48. (2017).

Driver, J. A., Logroscino, G., Gaziano, J. M. & Kurth, T. Incidence and remaining lifetime risk of Parkinson disease in advanced age. Neurology 72, 432–8 (2009).

Wright Willis, A., Evanoff, B. A., Lian, M., Criswell, S. R. & Racette, B. A. Geographic and ethnic variation in Parkinson disease: a population-based study of US Medicare beneficiaries. Neuroepidemiology 34, 143–51 (2010).

Zhang, Q. S., Heng, Y., Yuan, Y. H. & Chen, N. H. Pathological alpha-synuclein exacerbates the progression of Parkinson’s disease through microglial activation. Toxicol. Lett. 265, 30–7 (2017).

Heneka, M. T., Kummer, M. P. & Latz, E. Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 463–77 (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. Aggregated alpha-synuclein activates microglia: a process leading to disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 19, 533–42. (2005).

Spillantini, M. G. Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy are alpha-synucleinopathies. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 5, 157–62 (1999).

Beraud, D. & Maguire-Zeiss, K. A. Misfolded alpha-synuclein and Toll-like receptors: therapeutic targets for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18, S17–20 (2012).

Rogers, J., Mastroeni, D., Leonard, B., Joyce, J. & Grover, A. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: are microglia pathogenic in either disorder? Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 82, 235–46. (2007).

Sgobio, C. et al. Unbalanced calcium channel activity underlies selective vulnerability of nigrostriatal dopaminergic terminals in Parkinsonian mice. Sci. Rep. 9, 4857 (2019).

Jellinger, K. A. Neuropathology in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Acta Neuropathol. 120, 829–30 (2010).

Braak, H. et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 197–211 (2003).

Dauer, W. & Przedborski, S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 39, 889–909 (2003).

Bernheimer, H., Birkmayer, W., Hornykiewicz, O., Jellinger, K. & Seitelberger, F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington. Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J. Neurol. Sci. 20, 415–55 (1973).

Maroteaux, L., Campanelli, J. T. & Scheller, R. H. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J. Neurosci. 8, 2804–15 (1988).

Longhena, F., Faustini, G., Spillantini, M. G. & Bellucci, A. Living in promiscuity: the multiple partners of alpha-synuclein at the synapse in physiology and pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20,141 (2019).

Tofaris, G. K. et al. Pathological changes in dopaminergic nerve cells of the substantia nigra and olfactory bulb in mice transgenic for truncated human alpha-synuclein(1-120): implications for Lewy body disorders. J. Neurosci. 26, 3942–50 (2006).

Norris, E. H. et al. Reversible inhibition of alpha-synuclein fibrillization by dopaminochrome-mediated conformational alterations. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21212–9 (2005).

Dettmer, U., Newman, A. J., von Saucken, V. E., Bartels, T. & Selkoe, D. KTKEGV repeat motifs are key mediators of normal alpha-synuclein tetramerization: their mutation causes excess monomers and neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9596–601 (2015).

van Rooijen, B. D., van Leijenhorst-Groener, K. A., Claessens, M. M. & Subramaniam, V. Tryptophan fluorescence reveals structural features of alpha-synuclein oligomers. J. Mol. Biol. 394, 826–33 (2009).

Plotegher, N. et al. DOPAL derived alpha-synuclein oligomers impair synaptic vesicles physiological function. Sci. Rep. 7, 40699 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. Caspase-1 causes truncation and aggregation of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein alpha-synuclein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9587–92 (2016).

Peelaerts, W., Bousset, L., Baekelandt, V. & Melki, R. a-Synuclein strains and seeding in Parkinson’s disease, incidental Lewy body disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy: similarities and differences. Cell Tissue Res. 373, 195–212 (2018).

Surendranathan, A., Rowe, J. B. & O’Brien, J. T. Neuroinflammation in Lewy body dementia. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 1398–406 (2015).

Vieira, B. D., Radford, R. A., Chung, R. S., Guillemin, G. J. & Pountney, D. L. Neuroinflammation in multiple system atrophy: response to and cause of alpha-synuclein aggregation. Front. Cell Neurosci. 9, 437 (2015).

Valera, E. & Masliah, E. The neuropathology of multiple system atrophy and its therapeutic implications. Auton. Neurosci. 211, 1–6 (2018).

Wakabayashi, K. et al. Accumulation of alpha-synuclein/NACP is a cytopathological feature common to Lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol. 96, 445–52 (1998).

Lee, H. J., Suk, J. E., Bae, E. J. & Lee, S. J. Clearance and deposition of extracellular alpha-synuclein aggregates in microglia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 372, 423–8 (2008).

McGeer, P. L., Itagaki, S., Boyes, B. E. & McGeer, E. G. Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 38, 1285–91 (1988).

Bartels, T., De Schepper, S. & Hong, S. Microglia modulate neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Science 370, 66–9 (2020).

Kostuk, E. W., Cai, J. & Iacovitti, L. Regional microglia are transcriptionally distinct but similarly exacerbate neurodegeneration in a culture model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 15, 139 (2018).

Mastroeni, D. et al. Microglial responses to dopamine in a cell culture model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1805–17 (2009).

Kim, W. G. et al. Regional difference in susceptibility to lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in the rat brain: role of microglia. J. Neurosci. 20, 6309–16 (2000).

Mendiola, A. S. & Cardona, A. E. The IL-1beta phenomena in neuroinflammatory diseases. J. Neural Transm. 125, 781–95. (2018).

Griffin, W. S., Liu, L., Li, Y., Mrak, R. E. & Barger, S. W. Interleukin-1 mediates Alzheimer and Lewy body pathologies. J. Neuroinflammation. 3, 5 (2006).

Blum-Degen, D. et al. Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s and de novo Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci. Lett. 202, 17–20 (1995).

Daniele, S. G. et al. Activation of MyD88-dependent TLR1/2 signaling by misfolded alpha-synuclein, a protein linked to neurodegenerative disorders. Sci. Signal. 8, ra45 (2015).

Mogi, M. et al. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha are elevated in the brain from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci. Lett. 180, 147–50 (1994).

Mogi, M. et al. Interleukin (IL)-1 beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6 and transforming growth factor-alpha levels are elevated in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid in juvenile parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 211, 13–6 (1996).

Place, D. E. & Kanneganti, T. D. Recent advances in inflammasome biology. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 50, 32–8 (2018).

Latz, E., Xiao, T. S. & Stutz, A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 397–411 (2013).

Boucher, D. et al. Caspase-1 self-cleavage is an intrinsic mechanism to terminate inflammasome activity. J. Exp. Med. 215, 827–40 (2018).

Gaidt, M. M. & Hornung, V. Alternative inflammasome activation enables IL-1beta release from living cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 44, 7–13 (2017).

Kim, J. J. & Jo, E. K. NLRP3 inflammasome and host protection against bacterial infection. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28, 1415–23 (2013).

Schroder, K. & Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes. Cell 140, 821–32 (2010).

Bateman, G., Hill, B., Knight, R. & Boucher, D. Great balls of fire: activation and signalling of inflammatory caspases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 49, 1311–24. (2021).

Jain, A. et al. T cells instruct myeloid cells to produce inflammasome-independent IL-1beta and cause autoimmunity. Nat. Immunol. 21, 65–74 (2020).

Rubartelli, A. Redox control of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in health and disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 951–8 (2012).

Green, J. P. et al. Chloride regulates dynamic NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9371–E80. (2018).

Schmid-Burgk, J. L. et al. A genome-wide CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) screen identifies NEK7 as an essential component of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 103–9 (2016).

Prochnicki, T., Mangan, M. S. & Latz, E. Recent insights into the molecular mechanisms of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation. F1000Res. 5, F1000 (2016).

Pike, A. F. et al. alpha-Synuclein evokes NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1beta secretion from primary human microglia. Glia 69, 1413–28. (2021).

Freeman, D. et al. Alpha-synuclein induces lysosomal rupture and cathepsin dependent reactive oxygen species following endocytosis. PLoS ONE 8, e62143 (2013).

Vigano, E. et al. Human caspase-4 and caspase-5 regulate the one-step non-canonical inflammasome activation in monocytes. Nat. Commun. 6, 8761 (2015).

Baker, P. J. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation downstream of cytoplasmic LPS recognition by both caspase-4 and caspase-5. Eur. J. Immunol. 45, 2918–26 (2015).

Casson, C. N. et al. Human caspase-4 mediates noncanonical inflammasome activation against gram-negative bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6688–93 (2015).

Schmid-Burgk, J. L. et al. Caspase-4 mediates non-canonical activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in human myeloid cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 45, 2911–7 (2015).

Burm, S. M. et al. Inflammasome-induced IL-1beta secretion in microglia is characterized by delayed kinetics and is only partially dependent on inflammatory caspases. J. Neurosci. 35, 678–687 (2015).

Rathinam, V. A. K., Zhao, Y. & Shao, F. Innate immunity to intracellular LPS. Nat. Immunol. 20, 527–33 (2019).

Lagrange, B. et al. Human caspase-4 detects tetra-acylated LPS and cytosolic Francisella and functions differently from murine caspase-11. Nat. Commun. 9, 242 (2018).

Kayagaki, N. et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526, 666–71 (2015).

Kayagaki, N. et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117–21 (2011).

Shi, J. et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526, 660–5 (2015).

Kahns, S. et al. Caspase-1 and caspase-8 cleave and inactivate cellular parkin. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23376–80 (2003).

Mouton-Liger, F. et al. Parkin deficiency modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by attenuating an A20-dependent negative feedback loop. Glia 66, 1736–51 (2018).

Gao, H. M., Hong, J. S., Zhang, W. & Liu, B. Distinct role for microglia in rotenone-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 22, 782–90 (2002).

Gao, H. M. et al. Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 81, 1285–97 (2002).

Lee, E. et al. MPTP-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia plays a central role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 26, 213–28 (2019).

Martinez, E. M. et al. Editor’s highlight: Nlrp3 is required for inflammatory changes and nigral cell loss resulting from chronic intragastric rotenone exposure in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 159, 64–75 (2017).

Yan, Y. et al. Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell 160, 62–73 (2015).

Duda, J., Potschke, C. & Liss, B. Converging roles of ion channels, calcium, metabolic stress, and activity pattern of Substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons in health and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 139, 156–78 (2016).

Sulzer, D. & Surmeier, D. J. Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 28, 715–24 (2013).

Petrilli, V. et al. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 14, 1583–9 (2007).

Munoz-Planillo, R. et al. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 38, 1142–53 (2013).

Katsnelson, M. A., Rucker, L. G., Russo, H. M. & Dubyak, G. R. K+ efflux agonists induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently of Ca2+ signaling. J. Immunol. 194, 3937–52 (2015).

Yaron, J. R. et al. K(+) regulates Ca(2+) to drive inflammasome signaling: dynamic visualization of ion flux in live cells. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1954 (2015).

Mathur, A., Hayward, J. A. & Man, S. M. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 103, 233–57 (2018).

Yang, Y., Wang, H., Kouadir, M., Song, H. & Shi, F. Recent advances in the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its inhibitors. Cell Death Dis. 10, 128 (2019).

He, Y., Zeng, M. Y., Yang, D., Motro, B. & Nunez, G. NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature 530, 354–7 (2016).

Ahmed, S. & Booth, I. R. The use of valinomycin, nigericin and trichlorocarbanilide in control of the protonmotive force in Escherichia coli cells. Biochem. J. 212, 105–12 (1983).

Zhang, L., Zheng, Y., Xie, J. & Shi, L. Potassium channels and their emerging role in parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 160, 1–7 (2020).

Di, A. et al. The TWIK2 potassium efflux channel in macrophages mediates NLRP3 inflammasome-induced inflammation. Immunity 49, 56–65 e4 (2018).

Medhurst, A. D. et al. Distribution analysis of human two pore domain potassium channels in tissues of the central nervous system and periphery. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 86, 101–14 (2001).

Draheim, H. J. et al. Induction of potassium channels in mouse brain microglia: cells acquire responsiveness to pneumococcal cell wall components during late development. Neuroscience 89, 1379–90 (1999).

Sarkar, S. et al. Kv1.3 modulates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 4195–212 (2020).

Martel, P., Leo, D., Fulton, S., Berard, M. & Trudeau, L. E. Role of Kv1 potassium channels in regulating dopamine release and presynaptic D2 receptor function. PLoS ONE 6, e20402 (2011).

Fomina, A. F., Nguyen, H. M. & Wulff, H. Kv1.3 inhibition attenuates neuroinflammation through disruption of microglial calcium signaling. Channels 15, 67–78 (2021).

Nguyen, H. M. et al. Differential Kv1.3, KCa3.1, and Kir2.1 expression in “classically” and “alternatively” activated microglia. Glia 65, 106–21 (2017).

Fordyce, C. B., Jagasia, R., Zhu, X. & Schlichter, L. C. Microglia Kv1.3 channels contribute to their ability to kill neurons. J. Neurosci. 25, 7139–49 (2005).

Pannasch, U. et al. The potassium channels Kv1.5 and Kv1.3 modulate distinct functions of microglia. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 33, 401–11 (2006).

Di Lucente, J., Nguyen, H. M., Wulff, H., Jin, L. W. & Maezawa, I. The voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 is required for microglial pro-inflammatory activation in vivo. Glia 66, 1881–95 (2018).

Ma, D. C., Zhang, N. N., Zhang, Y. N. & Chen, H. S. Kv1.3 channel blockade alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by reshaping M1/M2 phenotypes and compromising the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia. Exp. Neurol. 332, 113399 (2020).

Zhu, J. et al. T-lymphocyte Kv1.3 channel activation triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway in hypertensive patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 14, 147–54 (2017).

Storey, N. M., Gomez-Angelats, M., Bortner, C. D., Armstrong, D. L. & Cidlowski, J. A. Stimulation of Kv1.3 potassium channels by death receptors during apoptosis in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33319–26 (2003).

Surmeier, D. J., Obeso, J. A. & Halliday, G. M. Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 101–13 (2017).

Loane, C. & Politis, M. Positron emission tomography neuroimaging in Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 3, 323–41 (2011).

Bega, D. et al. Clinical utility of DaTscan in patients with suspected Parkinsonian syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 43 (2021).

Hill, E., Gowers, R., Richardson, M. J. E. & Wall, M. J. alpha-Synuclein aggregates increase the conductance of substantia nigra dopamine neurons, an effect partly reversed by the KATP channel inhibitor glibenclamide. eNeuro 8, ENEURO.0330-20.2020 (2021).

Brichta, L. & Greengard, P. Molecular determinants of selective dopaminergic vulnerability in Parkinson’s disease: an update. Front. Neuroanat. 8, 152 (2014).

Damier, P., Hirsch, E. C., Agid, Y. & Graybiel, A. M. The substantia nigra of the human brain. II. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 122, 1437–48 (1999).

Hirsch, E., Graybiel, A. M. & Agid, Y. A. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Nature 334, 345–8 (1988).

Rice, M. E. & Cragg, S. J. Dopamine spillover after quantal release: rethinking dopamine transmission in the nigrostriatal pathway. Brain Res. Rev. 58, 303–13 (2008).

Yee, A. G. et al. Action potential and calcium dependence of tonic somatodendritic dopamine release in the Substantia Nigra pars compacta. J. Neurochem. 148, 462–79 (2019).

Ford, C. P., Gantz, S. C., Phillips, P. E. & Williams, J. T. Control of extracellular dopamine at dendrite and axon terminals. J. Neurosci. 30, 6975–83 (2010).

Gentet, L. J. & Williams, S. R. Dopamine gates action potential backpropagation in midbrain dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 27, 1892–901 (2007).

Beckstead, M. J., Grandy, D. K., Wickman, K. & Williams, J. T. Vesicular dopamine release elicits an inhibitory postsynaptic current in midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuron 42, 939–46 (2004).

Cragg, S. J. & Greenfield, S. A. Differential autoreceptor control of somatodendritic and axon terminal dopamine release in substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, and striatum. J. Neurosci. 17, 5738–46 (1997).

Heeringa, M. J. & Abercrombie, E. D. Biochemistry of somatodendritic dopamine release in substantia nigra: an in vivo comparison with striatal dopamine release. J. Neurochem. 65, 192–200 (1995).

Bjorklund, A. & Lindvall, O. Dopamine in dendrites of substantia nigra neurons: suggestions for a role in dendritic terminals. Brain Res. 83, 531–7 (1975).

Dominguez-Meijide, A., Rodriguez-Perez, A. I., Diaz-Ruiz, C., Guerra, M. J. & Labandeira-Garcia, J. L. Dopamine modulates astroglial and microglial activity via glial renin-angiotensin system in cultures. Brain Behav. Immun. 62, 277–90 (2017).

Bjorklund, A. & Dunnett, S. B. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 30, 194–202 (2007).

Lawson, L. J., Perry, V. H., Dri, P. & Gordon, S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience 39, 151–70 (1990).

McCarthy, M. M. Location, location, location: microglia are where they live. Neuron 95, 233–5 (2017).

Kempadoo, K. A., Mosharov, E. V., Choi, S. J., Sulzer, D. & Kandel, E. R. Dopamine release from the locus coeruleus to the dorsal hippocampus promotes spatial learning and memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14835–40 (2016).

Sonneborn, A. & Greene, R. W. Norepinephrine transporter antagonism prevents dopamine-dependent synaptic plasticity in the mouse dorsal hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 740, 135450 (2021).

Rangaraju, S., Gearing, M., Jin, L. W. & Levey, A. Potassium channel Kv1.3 is highly expressed by microglia in human Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 44, 797–808 (2015).

Heneka, M. T. et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493, 674–8 (2013).

Surmeier, D. J. & Sulzer, D. The pathology roadmap in Parkinson disease. Prion 7, 85–91 (2013).

Braak, H., Ghebremedhin, E., Rub, U., Bratzke, H. & Del Tredici, K. Stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 318, 121–34 (2004).

Xin, W. et al. Ventral midbrain astrocytes display unique physiological features and sensitivity to dopamine D2 receptor signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 344–55 (2019).

Mizee, M. R. et al. Isolation of primary microglia from the human post-mortem brain: effects of ante- and post-mortem variables. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 5, 16 (2017).

Halliday, G. M. & McCann, H. Human-based studies on alpha-synuclein deposition and relationship to Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Exp. Neurol. 209, 12–21 (2008).

Alegre-Abarrategui, J. et al. Selective vulnerability in alpha-synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 138, 681–704 (2019).

LeWitt, P. A. Levodopa therapy for Parkinson’s disease: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Mov. Disord. 30, 64–72 (2015).

Fernandez, H. H. et al. Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel in advanced Parkinson’s disease: final 12-month, open-label results. Mov. Disord. 30, 500–9 (2015).

Hoy, S. M. Levodopa/carbidopa enteral suspension: a review in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Drugs 79, 1709–18 (2019).

Teisseyre, A., Palko-Labuz, A., Sroda-Pomianek, K. & Michalak, K. Voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 as a target in therapy of cancer. Front. Oncol. 9, 933 (2019).

Santhanam, P. & Taieb, D. Role of (18) F-FDOPA PET/CT imaging in endocrinology. Clin. Endocrinol. 81, 789–98 (2014).

Nalls, M. A. et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol. 18, 1091–102 (2019).

Panicker, N. et al. Fyn kinase regulates misfolded alpha-synuclein uptake and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1411–30 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The work presented is part of the EU Joint Program-Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project “InCure” and was supported by the following funding organizations under the aegis of JPND: the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; funding code 733051051)(Netherlands; A.F.P. and R.V.) and the Ministry of Education, Universities, and Research (Italy; I.S. and L.B.). The work was also supported by Progetto Dipartimenti di Eccellenza MIUR “Biological signals: from cells to ecosystems” funding through the Department of Biology, University of Padua (A.F.P. and L.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.P. conceptualized and wrote the manuscript; I.S., R.V., and L.B. provided critical feedback and suggestions for the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pike, A.F., Szabò, I., Veerhuis, R. et al. The potential convergence of NLRP3 inflammasome, potassium, and dopamine mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 8, 32 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-022-00293-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-022-00293-z

This article is cited by

-

α7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: a key receptor in the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway exerting an antidepressant effect

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023)

-

Inflammasome activation in peritumoral astrocytes is a key player in breast cancer brain metastasis development

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2023)

-

PARK7/DJ-1 in microglia: implications in Parkinson’s disease and relevance as a therapeutic target

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023)

-

Neuromodulation in Parkinson’s disease targeting opioid and cannabinoid receptors, understanding the role of NLRP3 pathway: a novel therapeutic approach

Inflammopharmacology (2023)

-

Toll-like receptors and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pathways in Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications

Journal of Neurology (2023)