Abstract

TribaloyTM alloys are well-known as wear-resistant alloys, however, their oxidation kinetics and mechanisms are not well studied, especially their long-term oxidation behavior. In this work, the long-term isothermal oxidation behavior of TribaloyTM T400 and T800 in synthetic air at 900 °C for up to 1000 h was investigated. The mass gains of the samples were continuously recorded during the experiments with a thermobalance. Post mortem inspection of the samples was performed and the oxidation mechanism was analyzed. The results show that T800 has a better oxidation resistance than T400. The parabolic rate constant kp of T800 is 4.9·10−14 g2·cm−4·s−1, which is approximately one order of magnitude lower than 4.8·10−13 g2·cm−4·s−1 for T400. The penetration depth of the oxides in T800 is less than half of that in T400 and steady state oxidation is attained after approximately 200 h, compared to 350 h for T400. The better oxidation resistance of T800 correlates with its higher Cr content whereby protective Cr2O3 scales form more readily.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

TribaloyTM (a registered trademark of Kennametal Inc.) alloys are a group of Co or Ni-based superalloys which are extensively used as wear-resistant and corrosion-resistant coating materials for applications in which extreme wear is combined with high temperatures and corrosive media, such as industrial turbine applications.1,2,3,4,5 TribaloyTM alloys are composed of a large volume fraction of hard intermetallic Laves phase dispersed in a eutectic matrix of Laves phase and a Co- or Ni-based solid solution. These alloys can be used up to 800–1000 °C.6 The hard Laves phase is a ternary C14 MgZn2-type Laves phase with a melting point of about 1560 °C and compositions between approximately Co3Mo2Si and CoMoSi in Co-based TribaloyTM alloys. Their wear resistance of TribaloysTM alloys depends highly on the volume fraction of the Laves phase. T800 contains approximately 60 vol.% of Laves phase while T400 contains about 35 vol.% Laves phase.7,8 Table 1 lists the compositions of T400 and T800.9,10 Mo, Cr and Si are the main alloying elements in both alloys. The technical data sheet9 states that T800 exhibits exceptional oxidation and corrosion resistance because of its higher Cr content, however, its oxidation kinetics and mechanism are not well studied. T800 also exhibits higher hardness and better abrasive wear resistance than T400 because of its higher volume fraction of Laves phase.

Although high temperature oxidation behavior of chromia-forming alloys has been extensively investigated,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 little attention has been paid to the oxidation resistance of T400 and T800 alloys. The oxidation behavior of T400 was studied by do Nascimento et al.20 at 450 and 750 °C in air for 6 h and Sliney & Jacobson21 at 650 °C for 20 h. Zhang et al.22,23,24,25 studied the isothermal oxidation behavior of T80023 and T800 modified with additions of rhenium,24 yttrium and aluminum,25 and iron and aluminum22 in air at 800 °C and 1000 °C for up to 60 h. The oxidation behavior of an alloy strongly depends on time and temperature of exposure. It has been frequently shown that predicting long-term oxidation behavior on the basis of short-term results can be misleading.26,27,28 Because the oxidation of alloys forming a protective scale starts with an incipient “transient” stage before steady state oxidation is attained,29 it is important to determine the time when steady state oxidation begins and the parabolic rate constant at that stage for long-time service. In view of the expected service time, all previous experiments on T400 and T800 appear to be rather short. Moreover, previous oxidation studies showed that the oxide scales that form on T400 and T800 are rather complex and that the type of oxides crucially varies with temperature.

In the present work, long time oxidation experiments in synthetic air at 900 °C up to 1000 h have been carried out to determine the begin of steady state oxidation and parabolic rate constants of TribaloyTM T400 and T800 at a temperature which is interesting for long-term application of both alloys but where no information about their oxidation kinetics exists.

Results

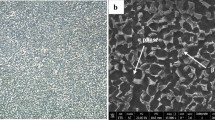

Figure 1 shows the microstructures of as-cast T400 and T800. Both alloys consist of dendritic primary Laves phase and a eutectic matrix consisting of Laves phase and a Co-based solid solution (Coss). Compared to T400, T800 has a larger volume fraction of Laves phase, which is consistent with literature.7,8 EPMA analyses show that the compositions of Laves phase and Coss differ quite markedly in the two alloys (Table 2). In accordance with the overall composition of the alloys, both phases are more Co rich in T400, while they have a higher Cr content in T800. In T400, an additional phase was detected, which, based on its analyzed composition, could be the Fe7W6-type μ phase.

Figure 2 shows the mass gains per unit area of both alloys as a function of time during isothermal oxidation in synthetic air at 900 °C. After 900 h, the mass gain per unit area is 3.3 mg/cm2 for T400, which is approximately two times larger than that of T800 (1.5 mg/cm2). To identify the time when the initial transient oxidation kinetics change to steady state and to determine the respective parabolic rate constants, the approach of local analysis of the mass-gain curves is applied by the equation:30

where t is the time (s), Δm is the mass gain (g) and S is the surface area (cm2). A, B and C are coefficients obtained from fitting, where C is always the reciprocal of the parabolic rate constant kp (g2·cm−4·s−1).30 In the fitting procedure, the time is identified for which C is constant, i.e., where continuous oxidation kinetics prevail.

The equation was adopted to analyze the thermogravimetric data using the software Mathematica (version 11.0, Wolfram Research, Inc.). The mass-gain data shown in Fig. 2 were fitted to Eq. (1) with a fit interval of 1 h over the entire duration to determine time periods, where C becomes constant. From these, kp was obtained from kp = C−1. The results reveal that for T800, steady state oxidation is attained after approximately 200 h, since its kp stays constant at a value of 4.9·10−14 g2·cm−4·s−1 afterwards. For T400, kp remains constant at 4.8·10−13 g2·cm−4·s−1 when the time exceeds about 350 h. The analysis of the mass-gain data shows that it takes considerable time at 900 °C before a protective oxide scale forms.

SEM BSE images of the cross sections of oxidized T400 and T800 are shown in Fig. 3. The oxide scales on both samples show considerable spallation. Because no weight losses were observed during oxidation (Fig. 2), spallation must have occurred during cooling to room temperature. Spallation of scales on Co based alloys has been reported before and has been attributed to the formation of voids inside the scale.31,32,33 Such voids in the oxide scale are also visible in Fig. 3. However, from the present results it is not clear whether the voids inside the oxide scale, voids at the metal/oxide interface or differences in the coefficients of thermal expansion of oxides and metal lead to the spallation of the scales during cooling. To preserve the remnants of the scales, the samples have been electrochemically coated with Ni before preparing the cross sections.

Due to the spallation of the scale and the marked protrusion of the oxides into the substrate, the width of the scales are also difficult to determine. According to Fig. 3, the widths could be approximately 10 μm on T400 and T800. The penetration depth of the oxides in T400 (Fig. 3a) ranges from about 20 to 80 μm, while the penetration depth in T800 (Fig. 3b) is much smaller (less than 20 μm).

The GI-XRD pattern in Fig. 4(a) shows that the oxide layer on T400 predominantly consists of Co2CrO4 spinel and certain amounts of CoMoO4 and SiO2. The oxide layer on T800 consists of CoMoO4, CoCr2O4, Cr2O3 and SiO2 (Fig. 4b). In addition, reflections from the substrate, i.e., Laves phase and Coss, are visible in the GI-XRD pattern of T800, but not in that of T400. This also indicates that the scale on T800 is considerably thinner than on T400, which correlates with the observations made on the cross sections (Fig. 3).

The phases have been further characterized by EPMA (Table 3). Due to the porous character of the oxides, EPMA analyses did not yield stoichiometric oxygen contents and analyses of oxides were therefore recalculated to stoichiometric compositions. For T400, the phases CoCr2O4 and Cr2O3 were identified in addition to Co2CrO4 and CoMoO4, which had already been found by GI-XRD. SiO2, which is also detected in the GI-XRD, is always present in a mixture of SiO2 and Cr2O3 (Fig. 6). Comparisons of the compositions of Laves phase and Coss in the interior of the samples and regions adjacent to the oxide scale reveal that near the oxides both phases contain less Cr than in the interior of the sample (Table 3). In addition to Laves phase and Coss, traces of a phase rich in Co and Mo were observed at the oxide/metal interface, which, according to its composition, could be the ε-phase (D019; Ni3Sn-type). EPMA analysis of the oxide scale on T800 confirmed the presence of CoMoO4, CoCr2O4 and Cr2O3. As is the case in T400, SiO2 is observed in a mixture of SiO2 and Cr2O3. Compared with T400, the oxide layer of T800 contains more Cr oxide but no Co2CrO4. This is consistent with the nominal compositions of both alloys, in that T800 has a much higher content of Cr but less Co than T400. There is also a difference in the Si content of 1.8 at.% between T800 and T400. However, according to the above results, this seems not to have a marked influence on the different oxidation performance of the two alloys.

Figure 5 shows element distribution maps of the cross sections of T400 and T800. For T400 the outer oxide layer is enriched in Co and Mo. GI-XRD and EPMA results indicate that this layer is a mixture of Co2CrO4 and CoMoO4. Underneath this layer is a continuous Cr2O3 layer, which is in direct contact with the substrate. The BSE images in Fig. 6 show that the Laves phase is preferentially attacked. Where the Laves phase is in contact with the oxide scale, CoCr2O4 is observed, while the interior of the former Laves phase shows a core-shell structure with Cr2O3 forming the shell and a mixture of Cr2O3 and SiO2 in the core.

The oxide layer on T800 has a similar stratigraphy compared with that on T400. The outer layer is CoMoO4, the inner layer is mainly composed of Cr2O3 with a small amount of CoCr2O4. The oxides inside the Laves phase are again a mixture of Cr2O3 and SiO2, but the protrusions are smaller and do not show a core-shell structure (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

In their fundamental study of the oxidation behavior of Co-Cr alloys, Phalnikar et al.11 found that the optimum Cr content for a maximum in oxidation resistance in these alloys is approximately 25 wt.%. At 900 °C they found that the parabolic rate constant (kp) for alloys with 8.5 wt.% Cr (corresponding to T400) is about one magnitude higher as for 17.5 wt.% Cr (T800), which correlates with the present finding that kp of T400 is one magnitude higher than kp of T800. They also found that up to 25 wt.% Cr the oxide scales consist of a mixture of spinel (Co3O4) and Cr2O3, and that Cr2O3, not spinel, is responsible for a good oxidation resistance. Although the above observations were made on binary Co-Cr alloys, they fully agree with the present ones. The oxide scale on T400 and T800 consists of spinels (CoCr2O4 (+Co2CrO4 for T400)) and Cr2O3. The XRD scans (Fig. 4) and the element distribution mappings (Fig. 5) show that the fraction of Cr2O3 is higher in the scale on T800 than on T400. Comparison with the Arrhenius plot for Cr2O3 forming alloys from Hindam & Whittle29 reveals that the kp of T400 and T800 from the present study is around one magnitude smaller than those given in literature.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 This discrepancy is attributed to the analysis method used.30 In previous works,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 the parabolic rate constants were calculated according to the simple parabolic rate law proposed by C. Wagner,19 which only satisfactorily applies to the oxidation kinetics of a limited number of pure metals at high temperature and underestimates the influence of the transient stage on the parabolic rate constants.30 In the present study, over 80% of the mass gain of T400 and T800 comes from the transient regime of faster kinetics, thus using Eq. (1) to calculate the parabolic rate constant is more accurate.30 It is worth mentioning that if the present thermogravimetric data were evaluated according to the simple parabolic rate law,19 the resulting parabolic rate constants perfectly fit into the range of 3·10−11 to 5·10−13 g2·cm−4·s−1, which is the typical range for Cr2O3 forming alloys at 900 °C determined in previous studies,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,29 indicating that Cr2O3 in the mixed oxide scale is responsible for the oxidation resistance of both alloys.

The difference in kp between T400 and T800 could be attributed to a difference in the thickness of Cr2O3, which forms a uniform layer according to previous reports.31,32,33 Though spallation of the scales on the present alloys makes any interpretation difficult, the present SEM and EPMA results suggest to another possibility. The element distribution map in Fig. 5 shows that the thickness of the Cr2O3 layer varies considerably, which is also confirmed by the EPMA analyses. In particular, where oxide protrusions are observed in T400, no Cr2O3 layer is detected (Fig. 5a). Instead, CoCr2O4 is observed (Fig. 6). The inferior oxidation resistance of T400 may therefore also be related to the fact that no continuous Cr2O3 layer formed on this alloy. For T800, steady state oxidation is observed after 200 h at 900 °C and it can be assumed that at that time the protective Cr2O3 scale has formed. Due to its lower Cr content, it takes somewhat longer before such a scale has formed on T400 and therefore steady state oxidation in this alloy is only observed after 350 h.

The protrusions, where the Cr2O3 layer seems to be interrupted, are due to preferential oxidation of the Laves phase. Though the main constituents of the Laves phase are Co and Mo (Table 2), the advancing protrusions have a layer of Cr2O3 in front (shell) and a mixture of Cr2O3 and SiO2 in the core. The analyses in the core of the protrusions reveal that nearly no Co and Mo are detected (Table 3). However, the composition of the Laves phase, which is in contact with the oxides, differs only slightly from its original composition except that it shows a slight depletion in Cr (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, compared with the initial composition, the composition of Coss that is in contact with the oxide reveals a substantial depletion in Cr, coupled with an increase in Co and Mo. The difference in the chemical potential which results from this concentration gradient acts as driving force for continued metal-ion diffusion.34,35

In view of previous findings, the present results can be explained as follows: For Co-Cr alloys, it has been found that the diffusion of Co ions is faster than that of Cr ions.11,34 Co diffuses outwards through the Cr2O3 scale and is then oxidized, forming an outer layer of Co oxides, which are CoMoO4 (T400, T800) and Co2CrO4 spinel (T400) in case of the present alloys. Mo is also only found in the outer parts of the oxide scale but the fraction of Mo-containing oxides is low. The reason for this could be that volatile Mo oxides formed during oxidation at 900 °C, e.g., MoO3, which is volatile above 700 °C,36,37 may have evaporated during oxidation.38 Underneath this outer layer CoCr2O4 spinel is detected and Cr2O3 is the innermost oxide. This sequence correlates with the observation made by Zhang and co-workers on T80011,12,13 and on the Co-base alloy Phynox after thermal cycling between 1100 °C and room temperature.32,33

After oxidation of T800 in air at 800 °C, Zhang et al.11 observed an outermost layer of mainly Co3O4, followed by CoMoO4 and CoCr2O4, and a layer mainly composed of MoO3 and a small amount of CoO. Beneath these external scales was a layer containing Cr2O3, MoO3, SiO2 and a small amount of CoO. A mixture of Cr2O3 and SiO2 was found inside the Laves phase. After oxidation at 1000 °C, the oxide scale was comparably simple, in that it consisted of an outer layer of CoCr2O4, which covered a layer of Cr2O3 and some SiO2 at the scale/substrate interface.11 No Mo-containing oxide was detected any longer after oxidation at 1000 °C. The current results cohere with the observations made by Zhang et al.11 MoO3 and CoO, which were observed at 800 °C, are no longer detected at 900 °C, but CoCr2O4, which was identified at 1000 °C, is also present at 900 °C. For T400, no comparative data on oxidation exist. The T400 coating oxidized at 450 and 750 °C reported by do Nascimoto et al.20 was diluted by the stainless steel substrate during deposition and therefore cannot be used as a reference. A comparison of the oxide scales formed on T400 and T800 at 900 °C reveals that the scale on T400 additionally contains the Co-rich spinel Co2CrO4, but a much smaller fraction of Cr2O3, and the oxides protrude deeper into the Laves phase. These observations can all be attributed to the lower Cr content in T400, which is why a protective Cr2O3 layer forms only after prolonged oxidation.

Methods

Bars of cast T400 and T800 were provided by Deloro Wear Solutions GmbH, Koblenz, Germany. Samples with a dimension of 10 × 10 × 2 mm3 were cut by electrical discharge machining (EDM) and then ground with emery papers down to 1200 grit. Before the oxidation experiments, the samples were cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with distilled water, degreased with acetone and dried in air. Isothermal oxidation experiments were carried out in a thermobalance (Setaram SETSYS 16/18) in flowing synthetic air (20.5% O2, 79.5% N2) at a flow rate of 1.54 × 10−6 m3/s at 900 °C. The heating and cooling rate were 10 and 5 °C/min, respectively. The mass gains of the samples were recorded continuously during the experiments. After oxidation, a Ni layer was deposited on the sample surface to protect the oxide layer during EDM cutting. Afterwards, the cross sections of the samples were ground and polished down to 1 μm. The microstructures of the samples were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Zeiss Gemini 500). Element distribution maps were recorded on a SEM (Zeiss Auriga) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS; EDAX Elect plus) and compositions of phases were determined with an electron probe micro analyzer (EPMA; JEOL JXA-8100l). The oxide scales were also characterized by grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GI-XRD; Seifert ID3003) using Co-Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.178897 nm) and an incidence angle of 2.0° and the 2θ range 10–120° was scanned in 2θ steps of 0.05° with a count time of 30 s per step.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schmidt, R. & Ferriss, D. New materials resistant to wear and corrosion to 1000 °C. Wear 32, 279–289 (1975).

Sahraoui, T., Fenineche, N.-E., Montavon, G. & Coddet, C. Alternative to chromium: characteristics and wear behavior of HVOF coatings for gas turbine shafts repair (heavy-duty). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 152, 43–55 (2004).

Sahraoui, T. et al. HVOF-sprayed Tribaloy-400: microstructure and first principle calculations. Mater. Lett. 58, 2433–2436 (2004).

Navas, C., Cadenas, M., Cuetos, J. M. & Damborenea, J. De Microstructure and sliding wear behaviour of Tribaloy T-800 coatings deposited by laser cladding. Wear 260, 838–846 (2006).

Tobar, M. J. et al. Characteristics of Tribaloy T-800 and T-900 coatings on steel substrates by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 202, 2297–2301 (2008).

Kennametal alloys brochure: hardfacing alloys. https://www.kennametal.com/content/dam/kennametal/kennametal/common/Resources/Catalogs-Literature/Stellite/B-18-05723_KMT_Stellite_Alloys_Brochure_Direct_update_LR.pdf

Halstead, A. & Rawlings, R. D. Structure and hardness of Co-Mo-Cr-Si wear resistant alloy. Metal. Sci. 18, 491–500 (1984).

Xu, W., Liu, R., Patnaik, P. C., Yao, M. X. & Wu, X. J. Mechanical and tribological properties of newly developed Tribaloy alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 452-453, 427–436 (2007).

TRIBALOYTM T-800 data sheet. https://www.deloro.com/s/Deloro-MDS-Tribaloy800-rev00.pdf

TRIBALOYTM T-400 data sheet. https://www.deloro.com/s/Deloro-MDS-Tribaloy400-rev00.pdf

Phalnikar, C. A., Evans, E. B. & Baldwin, W. M. High temperature scaling of cobalt-chromium alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 103, 429–438 (1956).

Wood, G. C. & Whittle, D. P. The mechanism of breakthrough of protective chromium oxide scales on Fe-Cr alloys. Corros. Sci. 7, 763–782 (1967).

Mortimer, D. & Post, M. L. The oxidation of Cr and an Fe-50% Cr alloy. Corros. Sci. 8, 499–512 (1968).

Wallwork, G. R. & Hed, A. Z. Mapping of the oxidation products in the ternary Co-Cr-Al system. Oxid. Met. 3, 213–227 (1971).

Ecer, G. M. & Meier, G. H. Oxidation of high-chromium Ni-Cr alloys. Oxid. Met. 13, 119–158 (1979).

Espevik, S., Rapp, R. A., Daniel, P. L. & Hirth, J. P. Oxidation of Ni-Cr-W ternary alloys. Oxid. Met. 14, 85–108 (1980).

Hodgkiess, T., Wood, G. C., Whittle, D. P. & Bastow, B. D. The oxidation of Ni-70 wt.% Cr in oxygen between 1073 and 1473 °K. Oxid. Met. 14, 263–277 (1980).

Moulin, P., Huntz, A. M. & Lacombe, P. Influence des phenomenes diffusionnels sur le mecanisme d’oxydation des alliages Ni-Cr. Acta Metall. 28, 745–756 (1980).

Chen, J. H., Rogers, P. M. & Little, J. A. Oxidation behavior of several chromia-forming commercial nickel-base superalloys. Oxid. Met. 47, 381–410 (1997).

Nascimento, E. M., do, Amaral, L. Mdo & D’Oliveira, A. S. C. M. Characterization and wear of oxides formed on CoCrMoSi alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 332, 408–413 (2007).

Sliney, H. E. & Jacobson, T. P. Friction and wear of plasma-sprayed coatings containing cobalt alloys from 25° to 650° in air. ASLE Trans. 24, 257–263 (1981).

Zhang, Y. D. & Yang, Z. Structure and oxidation behavior of Tribaloy alloy with iron and aluminum additions. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 14, 30–34 (2007).

Zhang, Y. D., Zhang, Z. G., Zhang, C. & Lan, H. Oxidation behaviour of Tribaloy T-800 alloy at 800 and 1000 °C. Oxid. Met. 70, 229–239 (2008).

Zhang, Y. D., Zhang, Z. G., Zhang, C. & Lan, H. Effect of Rhenium addition on isothermal oxidation behavior of Tribaloy T-800 alloy. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 23, 370–376 (2010).

Zhang, Y. D., Zhang, C., Lan, H., Hou, P. Y. & Yang, Z. G. Improvement of the oxidation resistance of Tribaloy T-800 alloy by the additions of yttrium and aluminium. Corros. Sci. 53, 1035–1043 (2011).

Tedmon, C. S. The effect of oxide volatilization on the oxidation kinetics of Cr and Fe‐Cr alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 113, 766–768 (1966).

Rahmel, A., Schütze, M. & Quadakkers, W. J. Fundamentals of TiAl oxidation-a critical review. Mater. Corros. 46, 271–285 (1995).

Türker, M. The long-term oxidation behaviour of ferritic ODS alloys at 1100–1200 °C in air and nitrogen-2% oxygen. Corros. Sci. 41, 1921–1935 (1999).

Hindam, H. & Whittle, D. P. Microstructure, adhesion and growth kinetics of protective scales on metals and alloys. Oxid. Met. 18, 245–284 (1982).

Monceau, D. & Pieraggi, B. Determination of parabolic rate constants from a local analysis of mass-gain curves. Oxid. Met. 50, 477–493 (1998).

Moskowitz, L. & Trelewicz, K. HVOF coatings for heavy-wear, high-impact applications. J. Therm. Spray. Technol. 6, 294–299 (1997).

Buscail, H., Riffard, F., Issartel, C. & Perrier, S. Oxidation mechanism of cobalt based alloy at high temperatures (800-1100°C). Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 47, 404–410 (2012).

Buscail, H., Rolland, R., Riffard, F., Issartel C., & Perrier, S. Cobalt-based alloy oxidation at high temperatures. Ceramika, Papers of the Commission on Ceramic Science, Polish Ceramic Bulletin 1–10 (Polish Academy of Science—Kraków Division, Kraków, Polish Ceramic Society, 2013).

Lund, C. H. & Wagner, H. J. Oxidation of nickel- and cobalt-based superalloys. Batelle Meml. Inst. DMIC Report. 214, 1–26 (1965).

Paul, A, Laurila, T, Vuorinen, V. & Divinski, S. V. Thermodynamics, diffusion and the Kirkendall effect in solids. (Springer: Switzerland, 2014).

Gulbransen, E. A., Andrew, K. F. & Brassart, F. A. Oxidation of molybdenum 550° to 1700 °C. J. Electrochem. Soc. 110, 952–959 (1963).

Rioult, F. A., Imhoff, S. D., Sakidja, R. & Perepezko, J. H. Transient oxidation of Mo-Si-B alloys: effect of the microstructure size scale. Acta Mater. 57, 4600–4613 (2009).

Senkov, O. N., Senkova, S. V., Dimiduk, D. M., Woodward, C. & Miracle, D. B. Oxidation behavior of a refractory NbCrMo0.5Ta0.5TiZr alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 47, 6522–6534 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. D. Monceau for valuable discussions, Ms. C. Merten for improving the English, Ms. A.V. Ramírez for the support on data analysis, Mr. B. Breitbach for GI-XRD measurement, Ms. I. Wossack for EPMA measurement, and Mr. T. Wickfeld and Mr. M. Bütow for EDM preparation of the samples. Financial support by the European Union’s research and innovation program Horizon 2020 under grant No 634135 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. preformed the experiments, data analysis and manuscript preparation. X.F. was responsible for the experimental analysis and manuscript preparation. V.M. preformed the experiments and data analysis. U.J. was responsible for sample preparation and manuscript preparation. M. P. supervised the study, preformed the data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, J., Fang, X., Marx, V. et al. Isothermal oxidation behavior of TribaloyTM T400 and T800. npj Mater Degrad 2, 38 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0060-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-018-0060-3

This article is cited by

-

Laves phases: a review of their functional and structural applications and an improved fundamental understanding of stability and properties

Journal of Materials Science (2021)