Abstract

Assessment of cancer predisposition syndromes (CPS) in childhood tumours is challenging to paediatric oncologists due to inconsistent recognizable clinical phenotypes and family histories, especially in cohorts with unknown prevalence of germline mutations. Screening checklists were developed to facilitate CPS detection in paediatric patients; however, their clinical value have yet been validated. Our study aims to assess the utility of clinical screening checklists validated by genetic sequencing in an Asian cohort of childhood tumours. We evaluated 102 patients under age 18 years recruited over a period of 31 months. Patient records were reviewed against two published checklists and germline mutations in 100 cancer-associated genes were profiled through a combination of whole-exome sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification on blood-derived genomic DNA. Pathogenic germline mutations were identified in ten (10%) patients across six known cancer predisposition genes: TP53, DICER1, NF1, FH, SDHD and VHL. Fifty-four (53%) patients screened positive on both checklists, including all ten pathogenic germline carriers. TP53 was most frequently mutated, affecting five children with adrenocortical carcinoma, sarcomas and diffuse astrocytoma. Disparity in prevalence of germline mutations across tumour types suggested variable genetic susceptibility and implied potential contribution of novel susceptibility genes. Only five (50%) children with pathogenic germline mutations had a family history of cancer. We conclude that CPS screening checklists are adequately sensitive to detect at-risk children and are relevant for clinical application. In addition, our study showed that 10% of Asian paediatric solid tumours have a heritable component, consistent with other populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic predisposition has been estimated to account for 4–10% of childhood cancers.1,2 However, recent genomic studies of paediatric cancer patients have suggested that 6–35% of children with cancer may harbour deleterious germline mutations associated with their disease,3,4,5,6,7 implying an underestimation of cancer predisposition syndrome (CPS) prevalence in the paediatric population. Identifying children with CPS has important clinical consequences for both patient and their family. First, diagnosis of CPS may facilitate decisions in clinical care such as modifying treatment plans to mitigate toxicity, initiating surveillance for early detection and intervention of secondary malignancies, or introducing targeted therapies.8,9 Second, family members identified to harbour the same germline mutation can be informed of their individual cancer risks, whereby appropriate cancer risk management and reproductive counselling can be provided.

However, for each child diagnosed with cancer, risk assessment for CPS has been, and remains, a tremendous challenge to the paediatric oncologist. Unlike adult cancers, age-of-onset is an unreliable indicator for CPS in paediatric patients. Furthermore, detection of CPS in children is complicated by the diverse and inconsistent presentations of recognizable clinical phenotypes and lack of clear associated family history.3,8 Therefore, the conundrum faced by most paediatric oncologists is navigating these complexities to identify at-risk children who will benefit from genetic testing and counselling. Several studies have attempted to assess risk factors that could reliably select for these patients.8,10,11,12,13 Overall, guidelines proposed through comprehensive expert panel reviews reveal several common criteria for recognizing children with CPS: specific neoplasms, medical/physical anomalies, family history and excessive toxicity of cancer therapy. These criteria are assembled in checklists to help paediatric oncologists screen for patients with CPS.

Most genomic profiling and clinical screening studies for paediatric cancer susceptibility are conducted on Caucasian populations. It is thus unknown whether their findings can extrapolate to Asian children. In this study, we aim to validate the utility of published checklists for screening children with CPS and in parallel, characterize the prevalence and spectrum of germline mutations in Asian patients with paediatric solid tumours through next-generation sequencing. We screened our prospectively enrolled cohort using two published clinical tools,12,13 and concurrently identified germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes using whole-exome sequencing and digital multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA). For a comprehensive evaluation of the genetic alterations, we further validated the somatic status of identified germline variants in prospectively collected patient tumours.

Results

Patient characteristics

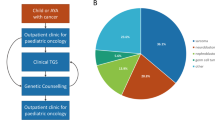

Our study included 102 children under age 18 years enrolled between January 2015 and August 2017. Patient characteristics and demographics are summarized in Table 1. According to national registry data, our cohort represents over 80% of all malignant paediatric tumours in Singapore.14,15 Fifty-two boys and 50 girls were included, with a median age at diagnosis of 4 years. Ethnic distribution was reflective of our population, comprising predominantly Chinese, followed by Indian, Malay and other ethnicities. The children presented a wide spectrum of solid tumours, broadly classified into ten histological groups (Fig. 1). Neuroblastic tumours are the most commonly observed, accounting for 19.6% (n = 20) of all solid tumours, followed by central nervous system (CNS) tumours in 11 (10.8%) children. A total of 26 (25.4%) patients presented with soft tissue and bone sarcomas of various histological classifications whereas 13 (12.7%) had Wilms tumour and 12 (11.8%) patients with extracranial germ cell tumours. The remaining children had neoplasms broadly grouped as endocrine or neuroendocrine (n = 6), ovarian (n = 5), hepatic (n = 5), and other rare tumours (n = 4), including pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB, n = 1), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (n = 1) and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (n = 2) (Supplementary Table 1).

Clinical checklist-aided screening for cancer predisposition syndrome

Using two published clinical checklists, we assessed 101 patients in our cohort for CPS. One patient was not evaluable due to insufficient clinical data. We found 79 (77.5%) and 66 (64.7%) patients with clinical features indicative of CPS based on the criteria proposed by Ripperger et al. or Postema et al. respectively,11,12,13 whereas ten (9.8%) patients were negative for both assessments (Table 2). Of the patients who screened positive, 54 (52.9%) met criteria in both checklists. Analysis of this group by tumour type revealed that patients with endocrine or neuroendocrine tumours are most likely to screen positive, while sarcoma patients were least likely to meet the criteria (Fig. 2). Both checklists were equally sensitive in detecting all ten patients with pathogenic germline mutations identified by sequencing (Table 2). While the use of each checklist independently was less specific, combining criteria of both checklists improved the specificity of detection to 52% without effect on sensitivity.

Of the ten patients who screened positive and carried pathogenic germline mutations, eight fulfilled clinical criteria for CPS including Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS, n = 3), DICER1 syndrome (n = 3), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (n = 1) and von Hippel-Lindau (VHL, n = 1) syndrome (Table 3). Nine patients were referred by their primary oncologist for genetic counselling and testing, of which four did not follow up with the recommendation. One patient was not referred due to rapid disease progression and succumbed to complications arising from her condition.

Spectrum of germline mutations in known cancer predisposition genes

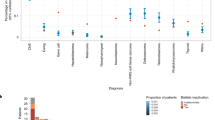

We identified 12 pathogenic germline mutations in 10 children (9.8%) across six known cancer predisposition genes (Table 3). Frequency of mutations was highest in TP53 affecting five patients, followed by DICER1 mutations in three patients (Fig. 3a). Two patients harboured more than one pathogenic variant: one with diffuse astrocytoma was found to have concurrent TP53 exon 1 deletion and NF1 nonsense mutation, and a Sertoli−Leydig cell tumour (SLCT) patient harboured both DICER1 frameshift and nonsense FH mutations. In addition, two patients were found with a deleterious mutation in VHL and SDHD respectively. Pathogenic variants in autosomal recessive genes were not observed.

Prevalence of pathogenic germline mutations. a Overview of identified pathogenic germline mutations across six genes in ten patients. b Lollipop diagrams visually depicting occurrence of the pathogenic germline mutations on proteins encoded by the affected genes. DA diffuse astrocytoma, ACC adrenocortical carcinoma, STS soft tissue sarcoma, RMS rhabdomyosarcoma, LPS liposarcoma, SLCT Sertoli−Leydig cell tumour, PPB pleuropulmonary blastoma, PC pheochromocytoma

All TP53 variants identified were previously seen in LFS families.16,17,18,19,20 Four of these were missense mutations that clustered within the p53 DNA-binding domain (Fig. 3b). Three (Cys141Tyr, Arg213Gln, Arg273Cys) are known to reduce p53 transactivation activity21,22, whereas Arg110Pro was demonstrated to have a dominant-negative effect on wild-type p53 function.23 Somatic loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) was observed in all TP53 mutation carriers, including the hemizygous exon 1 deletion carrier. TP53 exon 1 encodes the 5′ untranslated-region (UTR) shown to be critical for RPL26-mediated translation of p53 mRNA upon DNA damage.24 Reported carriers of TP53 promoter or exon 1 deletion mostly presented soft tissue sarcomas and breast cancer.20,25,26,27 Somatic LOH reflected by homozygous deletion of this region in our patient’s tumour (Supplementary Figure 1) implicates deleterious effect of this variation. Interestingly, this child also harboured a truncating germline mutation in NF1 (Arg1513*) previously observed in other NF1 patients.28,29,30

The three detected DICER1 germline mutations were truncating variants, two of which are reported in ClinVar database. A second DICER1 somatic mutation was found in all three patients at the RNase IIIb domain hotspot Glu1813 residue known to inactivate DICER1 activity31,32 (Fig. 3b). A concurrent truncating FH mutation with somatic LOH was seen in one of the DICER1 germline mutation carriers (Table 3).

Amongst the tumour types, prevalence of pathogenic germline mutation was highest in endocrine or neuroendocrine tumours (n = 4/6, 67%). This is followed by ovarian tumour (n = 2/5, 40%), soft tissue sarcoma (n = 2/18, 11%) and CNS tumour (n = 1/11, 9%) (Fig. 2). Further breakdown by histological subtypes highlighted that all enrolled patients with adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), pheochromocytoma and SLCT harboured germline mutations, implying a higher genetic susceptibility in these tumour types (Supplementary Table 2).

Association of germline mutations with clinical phenotype and family history

Overall, the detected genotypes were consistent with patient clinical phenotypes. Four among five TP53 mutation carriers presented tumours typical of LFS spectrum: ACC (n = 2) and soft tissue sarcoma (n = 2) (Fig. 3a). Moreover, their mutations were also reported in LFS families and paediatric patients with similar tumour types.3,16,17,18,33 Similarly, germline mutations in SDHD and VHL, two genes known to confer susceptibility to pheochromocytoma, were found in both patients with this diagnosis (Fig. 3a). Unsurprisingly, our DICER1 germline mutation carriers presented tumour types most frequently associated with DICER1 syndrome, namely PPB (n = 1) and SLCT with multinodular goitre (MNG) (n = 2).32

In patients harbouring more than one pathogenic germline mutation, clinical manifestations were predominantly consistent with genes in which penetrance is greater at an earlier age. For instance, the 2.6-year-old diffuse astrocytoma patient with concurrent NF1 and TP53 mutations exhibited clinical features mostly characteristic of NF1: multiple café-au-lait spots, neurofibroma and global developmental delay. This is congruent with the fact that penetrance is almost 100% by age 8 years in NF1 germline mutation carriers34 compared to penetrance of 50% by the third decade of life in individuals with germline TP53 mutations.35 However, the presence of astrocytoma unrelated to the optic pathway at this age is more consistent with the germline TP53 mutation harboured by this child, which was missed by the treating physicians given his characteristic NF1 clinical features.

Six of the ten germline mutation carriers had at least one relative with cancer (Table 3); however, only five (50%) showed a family history typical of CPS. Two are TP53 mutation carriers, who met Chompret criteria for LFS, whereas two DICER1 mutation carriers with SLCT had multiple relatives presenting MNG and thyroid cancer. The remaining VHL mutation carrier demonstrated a family history of pheochromocytoma and renal cell carcinoma consistent with VHL syndrome.

Variants of uncertain significance in known cancer predisposition genes

A total of 86 rare variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were detected, predominantly in neuroblastic tumours with an adjusted frequency of four variants, followed by soft tissue sarcoma with three VUS (Supplementary Figure 1). Amongst these, some were predicted potentially deleterious by in silico algorithms and occurred in DNA repair genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, MLH1, PMS2 and RAD54L. Coincidentally, tumours of patients from these two histological subtypes exhibited higher incidences of karyotypic aberrations, suggesting plausible roles for DNA repair pathway deficiency.

A few potentially deleterious VUS were found in genes beyond those commonly associated with the disease. For example, a variant in MAX, an essential interacting partner of MYC, was identified in a patient with neuroblastoma. The mutation Arg100Cys, which occurred within the leucine-zipper domain of MAX important for regulation of MYC, could impair MYC activities. Additionally, we found two variants—CDH1 Pro373Leu and RAF1 Pro332Ala—individually associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC)36 and childhood-onset dilated cardiomyopathy37 in two patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and testicular germ cell tumour respectively. Although demonstrated to be functionally deleterious, association of these VUS with the clinical phenotype of our patients remains to be verified by further studies.

Discussion

Although genomic sequencing has expanded our understanding of paediatric cancer predisposition and presented opportunities for genetics-mediated care, identifying children at-risk remains a clinical challenge for paediatric oncologists. Expert panels have deliberated over clinical and genetic attributes of multitude predisposition syndromes and assembled checklists aimed at facilitating detection of these children. Our study evaluated two such clinical tools in an Asian cohort of paediatric solid tumours and found both sufficiently sensitive for identifying at-risk children. Combining the criteria of both checklists saw a marked improvement in specificity, implicating possibility of increasing stringency in evaluation without compromising sensitivity of screening.

Our data reflected disparity in the yield of germline mutation carriers compared to clinically positive screenings (Fig. 2), implying that utility of the clinical checklists might vary by tumour types. This discordance could be attributed to several factors. First, our data together with other studies demonstrated variable prevalence of genetic susceptibility in different paediatric tumours, ranging from <5% in neuroblastoma and Wilms tumour to over 50% in ACC and pheochromocytoma.3,38,39,40 Second, while tumours such as ACC are strongly correlated with well-known susceptibility genes and CPS, e.g. TP53 and LFS, genetic alterations in tumours that are associated with little-known CPS or susceptibility genes are likely underestimated. Thus, lack of detectable germline mutations in subtypes such as neuroblastic tumours may be attributed to alterations in genes and CPS beyond the currently defined spectrum investigated. Hence, while our study demonstrated clinical relevance of these checklists, it cautioned for careful tumour type-specific considerations in application of this tool and more importantly, highlights the need for further research into novel susceptibility genes associated with childhood tumours.

Prevalence of pathogenic germline mutations identifiable by next-generation sequencing in our Asian cohort is 9.8%, consistent with the range of 8–10% observed in other studies.3,5,7 This is despite exclusion of haematologic malignancies and a lower incidence of CNS tumours, which were previously reported with a greater than average prevalence of germline mutations.4 Taken together, our study confirms that genetic predisposition accounts for approximately 10% of all childhood solid tumours, which is consistent with the prevalence of 8% observed in adult cancers.41

Nevertheless, this prevalence in genetic susceptibility is potentially a conservative estimate limited to our current knowledge of CPS and spectrum of associated genes. Approximately 50% of our patients who screened positive either harboured a VUS or had clinical features strongly suggestive of CPS. For instance, the germline mutation CDH1 Pro373Leu previously identified in an HDGC family and shown to impair E-cadherin in vitro36 was detected in our HCC patient. Although presently classified as a VUS due to insufficient evidence for its role in HCC tumourigenesis, it is imperative that variants of uncertain significance are periodically reviewed as new research uncovers novel genotype−phenotype associations.

Presentation of unusual neoplasms for a diagnosed CPS may stem from multiple pathogenic germline mutations, as demonstrated in our NF1 patient presenting with diffuse astrocytoma at age 2.6 years who was subsequently found to also harbour a pathogenic germline TP53 mutation. Children with NF1 are predisposed to CNS tumours typically of pilocytic astrocytoma subtype in the optic pathway, often accompanied by complete inactivation of NF1 through somatic events.42 Grade II gliomas such as diffuse astrocytoma are uncommon in paediatric patients and more frequently associated with TP53 inactivation.43 Intriguingly, somatic TP53 LOH, but not NF1, was observed in our patient’s tumour. Deficiency of p53 prior to NF1 loss has been correlated with complete penetrance of malignant astrocytomas in mice44 and could explain the histological subtype presented by our patient. Also noteworthy is that deletion of the TP53 exon 1 in this patient was not detected on whole-exome sequencing but identified through MLPA, hence would have been also missed by next-generation sequencing panels currently utilized for clinical genetic testing. This demonstrates the limitations of next-generation sequencing panels and highlights the need to include comprehensive capture of larger copy number alterations as well as untranslated gene regions in clinical genetic testing.

As with similar studies on germline variation in cancer,3,41 the rarity of paediatric solid tumours and diverse histological subtypes in this study precluded statistical significance in observed associations. Furthermore, detection of pathogenic germline mutations is limited to known cancer predisposition genes. Genetically unresolved cases may have pathogenic germline mutations in novel predisposition genes5 and data on VUS from our study highlights the particular tumour types that could benefit from further research into novel cancer predisposition genes.

In conclusion, our study validated two clinical checklists for detection of children at risk of CPS, and demonstrated that heritable predisposition accounts for at least 10% of Asian paediatric solid tumours. Application of these checklists is expected to improve identification of children at risk of CPS and referral for genetic testing, with significant implications on treatment strategies and clinical care for paediatric solid tumour patients and their families.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

Patients consulted at our paediatric oncology clinic at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and the Cancer Genetics Service at National Cancer Centre Singapore were prospectively recruited for this study. In all, 102 patients under age 18 years of various solid tumour types were included. Data on clinical history, tumour histology, treatment modalities and family history of cancer were collated. Collected peripheral blood and excess tissues from routine tumour biopsies or resections were stored at −80 °C. All tumour specimens were evaluated by a consultant pathologist to be representative lesional tissue on frozen section histology. This study was approved by SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (IRB 2018/2456, 2014/2079) with signed informed consent from patients and guardians.

Cancer predisposition syndrome screening checklist

To validate the utility of clinical checklists for screening paediatric patients at risk of CPS, collated clinical data were assessed independently against two published guidelines.11,12,13 Broadly, criteria outlined in the two checklists for consideration included family history of cancer, aberrant tumour genetics, multiple malignancies in the index patient, congenital defects, excessive toxicity related to cancer therapy, and specific tumour types that have been reported to frequently associate with syndromic disorders. Patient records were reviewed and given a positive score if one or more criteria was fulfilled for each checklist.12,13

Whole-exome sequencing

Genomic DNA from blood and tissue specimens were extracted using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified DNA was sheared to 200 base pairs (bp) and exome captured using Agilent SureSelect V6 kit. Constructed libraries were sequenced on Illumina Hiseq4000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to an average depth of 72× with over 92% of target bases covered >20×.

Variant prioritization pipeline

Sequenced reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hs37d5) using Burrows−Wheeler Aligner (BWA) and variants called using Freebayes, as detailed under Supplementary Methods. Variants were filtered by read depth (10×) and quality score (Phred score > 30), annotated using ANNOVAR and curated in a stepwise manner into five classifications: pathogenic, likely pathogenic, VUS, likely benign, benign. To identify candidate variants in autosomal dominant cancer predisposition genes (Supplementary Table 3), we filtered for rare coding and splice-site variants, determined by a minor allele frequency (MAF) of ≤0.1% in Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), 1000 Genomes (1000G) databases and our in-house database of local population (n = 1412). Truncating, splice-site and missense variants with a REVEL score of ≥0.6 and/or a Phred-scaled CADD score of ≥20 or without annotation were assessed for pathogenicity by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines.45 For autosomal recessive genes (Supplementary Table 3), we applied an MAF ≤5% threshold and curated only homozygous variants or two compound heterozygous variants within the same gene by ACMG guidelines. All other variants failing to meet criteria for benign/likely benign/likely pathogenic/pathogenic classifications by ACMG guidelines were classified as VUS. Protein domains were visualized using ProteinPaint.46

Digital multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis

MLPA targeting 29 hereditary cancer genes (Supplementary Table 4) was performed on patient genomic DNA as previously described27 and data analysed in collaboration with the manufacturer using a pre-release version of Coffalyser.Net (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Validation of variants

Candidate variants were validated by Sanger sequencing using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (ABI, ThermoFisher Scientific Corporation) and resulting chromatograms analysed using Mutation Surveyor (Softgenetics, PA, USA). Copy number variants detected through MLPA were validated by quantitative PCR. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to GAPDH endogenous control and fold-change in gene dosage was calculated using the ΔΔCt method by normalizing against two healthy controls. Somatic status of variants was similarly validated on tumour DNA.

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics and sequencing results were tabulated with descriptive statistics including median, interquartile range and proportions.

Data availability

All sequencing data from this study are publicly available at European Nucleotide Archive (accession PRJEB28383).

References

Narod, S. A., Stiller, C. & Lenoir, G. M. An estimate of the heritable fraction of childhood cancer. Br. J. Cancer 63, 993–999 (1991).

Strahm, B. & Malkin, D. Hereditary cancer predisposition in children: genetic basis and clinical implications. Int. J. Cancer 119, 2001–2006 (2006).

Zhang, J. et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2336–2346 (2015).

Kline, C. N. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of pediatric neuro-oncology patients improves diagnosis, identifies pathogenic germline mutations, and directs targeted therapy. Neuro-Oncol. 19, 699–709 (2017).

Parsons, D. W. et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5699 (2016).

Plon, S. E. et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility to childhood cancer through analysis of genes in parallel. Cancer Genet. 204, 19–25 (2011).

Gröbner, S. N. et al. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25480 (2018).

Jongmans, M. C. J. et al. Recognition of genetic predisposition in pediatric cancer patients: an easy-to-use selection tool. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 59, 116–125 (2016).

Postema, F. A. M., Hopman, S. M. J., Hennekam, R. C. & Merks, J. H. M. Consequences of diagnosing a tumor predisposition syndrome in children with cancer: a literature review. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 65, https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26718 (2018).

Knapke, S., Nagarajan, R., Correll, J., Kent, D. & Burns, K. Hereditary cancer risk assessment in a pediatric oncology follow-up clinic. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 58, 85–89 (2012).

Postema, F. A. M. et al. Childhood tumours with a high probability of being part of a tumour predisposition syndrome; reason for referral for genetic consultation. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 80, 48–54 (2017).

Postema, F. A. M. et al. Validation of a clinical screening instrument for tumour predisposition syndromes in patients with childhood cancer (TuPS): protocol for a prospective, observational, multicentre study. BMJ Open 7, e013237 (2017).

Ripperger, T. et al. Childhood cancer predisposition syndromes-A concise review and recommendations by the Cancer Predisposition Working Group of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 173, 1017–1037 (2017).

Tan, A. M. & Christina H. A. First Report of the Singapore Childhood Cancer Registry, 1997−2005.

Tan, A. M. & Ha, C. Singapore Childhood Cancer Registry 2003−2007 https://www.nrdo.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/Publications-Cancer/sccr-monograph-combined-v1-4.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

Bougeard, G. et al. Detection of 11 germline inactivating TP53 mutations and absence of TP63 and HCHK2 mutations in 17 French families with Li-Fraumeni or Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 38, 253–257 (2001).

Ruijs, M. W. G. et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li-Fraumeni syndrome: mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 47, 421–428 (2010).

Frebourg, T. et al. Germ-line p53 mutations in 15 families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56, 608–615 (1995).

Bouaoun, L. et al. TP53 variations in human cancers: new lessons from the IARC TP53 database and genomics data. Hum. Mutat. 37, 865–876 (2016).

Zerdoumi, Y. et al. Drastic effect of germline TP53 missense mutations in Li-Fraumeni patients. Hum. Mutat. 34, 453–461 (2013).

Monti, P. et al. Transcriptional functionality of germ line p53 mutants influences cancer phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3789–3795 (2007).

Monti, P. et al. Dominant-negative features of mutant TP53 in germline carriers have limited impact on cancer outcomes. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 271–279 (2011).

Xu, J. et al. Gain of function of mutant p53 by coaggregation with multiple tumor suppressors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 285–295 (2011).

Chen, J. & Kastan, M. B. 5’-3’-UTR interactions regulate p53 mRNA translation and provide a target for modulating p53 induction after DNA damage. Genes Dev. 24, 2146–2156 (2010).

Bougeard, G. et al. Molecular basis of the Li–Fraumeni syndrome: an update from the French LFS families. J. Med. Genet. 45, 535–538 (2008).

Varley, J. M. et al. Germ-line mutations of TP53 in Li-Fraumeni families: an extended study of 39 families. Cancer Res. 57, 3245–3252 (1997).

Chan, S. H. et al. Germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes are frequent in sporadic sarcomas. Sci. Rep. 7, 10660 (2017).

Side, L. et al. Homozygous inactivation of the NF1 gene in bone marrow cells from children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and malignant myeloid disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 336, 1713–1720 (1997).

Jeong, S.-Y., Park, S.-J. & Kim, H. J. The spectrum of NF1 mutations in Korean patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Korean Med. Sci. 21, 107–112 (2006).

Ko, J. M., Sohn, Y. B., Jeong, S. Y., Kim, H.-J. & Messiaen, L. M. Mutation spectrum of NF1 and clinical characteristics in 78 Korean patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatr. Neurol. 48, 447–453 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. The oncogenic roles of DICER1 RNase IIIb domain mutations in ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Neoplasia N. Y. N. 17, 650–660 (2015).

Foulkes, W. D., Priest, J. R. & Duchaine, T. F. DICER1: mutations, microRNAs and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 662–672 (2014).

Mitchell, G. et al. High frequency of germline TP53 mutations in a prospective adult-onset sarcoma cohort. PLoS ONE 8, e69026 (2013).

Patil, S. & Chamberlain, R. S. Neoplasms associated with germline and somatic NF1 gene mutations. Oncologist 17, 101–116 (2012).

Sagne, C. et al. Age at cancer onset in germline TP53 mutation carriers: association with polymorphisms in predicted G-quadruplex structures. Carcinogenesis 35, 807–815 (2014).

Corso, G. et al. Characterization of the P373L E-cadherin germline missense mutation and implication for clinical management. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 33, 1061–1067 (2007).

Dhandapany, P. S. et al. RAF1 mutations in childhood-onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet. 46, 635–639 (2014).

Wasserman, J. D. et al. Prevalence and functional consequence of TP53 mutations in pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: a children’s oncology group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 602–609 (2015).

Gadd, S. et al. A Children’s Oncology Group and TARGET initiative exploring the genetic landscape of Wilms tumor. Nat. Genet. 49, 1487–1494 (2017).

Pugh, T. J. et al. The genetic landscape of high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat. Genet. 45, 279–284 (2013).

Huang, K. et al. Pathogenic germline variants in 10,389 adult cancers. Cell 173, 355–370.e14 (2018).

Evans, D. G. R. et al. Cancer and central nervous system tumor surveillance in pediatric neurofibromatosis 1. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, e46–e53 (2017).

Rodriguez, F. J., Vizcaino, M. A. & Lin, M.-T. Recent advances on the molecular pathology of glial neoplasms in children and adults. J. Mol. Diagn. 18, 620–634 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Early inactivation of p53 tumor suppressor gene cooperating with NF1 loss induces malignant astrocytoma. Cancer Cell 8, 119–130 (2005).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–423 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Exploring genomic alteration in pediatric cancer using ProteinPaint. Nat. Genet. 48, 4–6 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients and research participants for their contribution to this study. We also acknowledge Chik Hong Kuick (KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital) for assistance with histopathological data, MRC-Holland for the reagents and analysis support in performing digitalMLPA, and SingHealth Duke-NUS Institute of Precision Medicine (PRISM) for bioinformatics support. This work was supported by the VIVA Foundation for Children with Cancer to A.H.P.L., and National Medical Research Council Singapore Clinician-Scientist Award (grant number: NMRC/CSA-INV/0017/2017) and Tan Cheng Lim Research & Education Fund Grant to J.N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H.C., J.N., and A.H.P.L. conceived and designed the study. Data acquisition, analysis and interpretation was carried out by S.H.C., W.C., N.D.B.I., W.K.L., S.-T.L., S.H.T., J.X.T., T.S., A.H.P.L., and J.N. Manuscript was drafted by S.H.C., A.H.P.L., J.N. with critical revision from all authors. S.H.T., K.C., Y.C., P.I., E.E.K.T., M.S.-F.S., M.Y.C., A.M.T., S.Y.Y.L., S.Y.S., and A.H.P.L. provided administrative, technical, and material support. J.N. and A.H.P.L. supervised the study. J.N. is the guarantor of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, S.H., Chew, W., Ishak, N.D.B. et al. Clinical relevance of screening checklists for detecting cancer predisposition syndromes in Asian childhood tumours. npj Genomic Med 3, 30 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-018-0070-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41525-018-0070-7

This article is cited by

-

Clinical trio genome sequencing facilitates the interpretation of variants in cancer predisposition genes in paediatric tumour patients

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Mutations of 1p genes do not consistently abrogate tumor suppressor functions in 1p-intact neuroblastoma

BMC Cancer (2022)

-

Clinical value of a screening tool for tumor predisposition syndromes in childhood cancer patients (TuPS): a prospective, observational, multi-center study

Familial Cancer (2021)