Abstract

We present a comprehensive theoretical study of conventional superconductivity in cubic antiperovskites materials with composition XYZ3 where X and Z are metals, and Y is H, B, C, N, O, and P. Our starting point are electron–phonon calculations for 397 materials performed with density-functional perturbation theory. While 43% of the materials are dynamically unstable, we discovered 16 compounds close to thermodynamic stability and with Tc higher than 5 K. Using these results to train interpretable machine-learning models, leads us to predict a further 57 (thermodynamically unstable) materials with superconducting transition temperatures above 5 K, reaching a maximum of 17.8 K for PtHBe3. Furthermore, the models give us an understanding of the mechanism of superconductivity in antiperovskites. The combination of traditional approaches with interpretable machine learning turns out to be a very efficient methodology to study and systematize whole classes of materials and is easily extendable to other families of compounds or physical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskites are one of the better known and more extensively studied family of ternary compounds. Of general formula XYZ3, they crystallize in a structure that is derived from a simple cubic lattice, that can easily tolerate distortions from intercalations, dopants and defects1. They find applications in a multitude of technological domains, such as photovoltaics2,3,4,5, piezoelectricity6, magnetism7, thermoelectricity8, lasing9,10, multiferroicity11, etc. One field where perovskites have a pivotal role is superconductivity. In fact, the cuprate ceramics that hold the record for the highest transition temperature (Tc) belong to this family12. These are complex oxide materials that exhibit an exotic superconducting state with d-wave paring13,14,15 resulting from an electronic pairing mechanism.

In 2001, He et al. reported the surprising discovery of superconductivity at 8 K in a non-oxide perovskite, MgCNi316. The high relative proportion of Ni in this compound suggested that magnetic interactions were important, and the relatively low Tc when compared to its two-dimensional analog (the LnNi2B2C family) led the authors to argue for a non-conventional mechanism. These claims were however quickly dismissed, and MgCNi3 is now acknowledged as an s-wave superconductors with a paring mechanism mediated by the electron–phonon interaction17.

These findings sparked the interest of researchers, and other related materials were found to be superconducting in the following years. Several other carbide, boride, and even nitride and oxide antiperovskites were proved experimentally to be superconductors, and a few other were predicted by theory (see Table 1). The maximum transition temperature measured experimentally was 10 K for InBLa3 and InOLa318, although higher Tc were predicted by theory for materials, such as RhNCr319 or TlBSc320.

Standard perovskites, such as the high-Tc superconductors, have a nonmetal atom (for instance, oxygen, a halide, or even nitrogen21,22) in the Z-position that corresponds to the vertices of the characteristic octahedra (see Fig. 10). MgCNi3 is different, in the sense that the nonmetal is in the Y-position at the center of the octahedra, and therefore belongs to the family of antiperovskites23 (also referred to as inverted or intermetallic perovskites). Among others, this family includes several borides and carbides24 (such as MgCNi3, GaCMn3, ZnCMn3, SnCMn3, etc.). These are very interesting materials23 as they can exhibit superconductivity16,25 and magnetism26,27, they can be used to strengthen aluminum-alloyed steels28 or as fast alkali ionic conductors29, etc.

In this work, we study conventional superconductivity in the family of inverted perovskites. Our objective is not only to investigate the physics of specific systems, but to understand the overall behavior of the whole family of compounds. We note that such large-scale studies are still rare in the literature, and we are only aware of one high-throughput study in hydrids under high pressure30.

We use a combination of standard methods with newer machine-learning methods. Specifically, we employ density-functional perturbation theory to calculate the electron–phonon properties. For the machine learning, we choose algorithms that not only have the ability to predict the relevant physical properties (the electron–phonon coupling strength λ and the averaged phonon frequency \({\omega }_{\log }\)), but are also capable of providing an interpretation of the data.

Results

High throughput

We selected all inverted perovskites with H, B, C, N, O, and P that were studied in the systematic work of ref. 31. We then filtered out the ones that the original calculation, performed with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) approximation32, yielded as semiconducting and magnetic. As expected, the number of materials increases rather rapidly with the distance to the convex hull. To keep the number of systems manageable, we decided to calculate inverted perovskites with distances to the convex hull, as calculated in ref. 31, smaller than 50 meV/atom. We discuss other compounds farther from the hull in “Machine learning”. Finally, we eliminated the systems that included chemical elements for which the PSEUDODOJO33 did not provide a pseudopotential.

In total, we calculated 397 systems within 50 meV/atom of the hull as calculated in ref. 31, of which 120 contained H, 45 with B, 66 with C, 93 with N, 56 with O, and 17 with P. We then calculated λ, \({\omega }_{\log }\), and Tc as explained in “Methods”. Of course, not all systems were dynamically stable, and we found imaginary frequencies for 169 compounds. In many cases, these appeared only at the edges of the Brillouin zone, and corresponded to vibrations of the Z-atoms (i.e., of the octahedra). As many perovskites exhibit structures where the octahedra are tilted and rotated, this is expected. The imaginary frequencies merely indicate that the five-atom cubic cell is unstable with respect to such distortions of the octahedra. Obviously, we did not consider these dynamically unstable compounds in our analysis of the results. Finally, we failed to converge the calculations for two compounds.

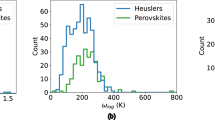

An overview of our data can be found in the blue curves of Fig. 1. In panel a, we can see that the distribution of values of λ is very asymmetric and peaked at around 0.25, indicating that most systems have a very weak electron–phonon coupling. Furthermore, it exhibits a fat tail that extends to values larger than one, i.e., into the so-called strong coupling regime. The distribution of values of \({\omega }_{\log }\) (panel b) is quite different: it is quite symmetric and goes quickly to zero not exhibiting any fat tail. The peak of the distribution is at around 250 cm−1, a relatively small value especially when we consider those very light chemical elements occupy the Y-atom in the antiperovskite structure. We also would like to note that the values of λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\) are not completely independent. In fact, systems with soft phonons, i.e., materials close to structural instabilities, will often exhibit large values for the electron–phonon coupling constant, leading to a degree of anti-correlation between λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\). Finally, in panel c of Fig. 1 we see the distribution of values of the superconducting transition temperature Tc. Not surprisingly, the overwhelming majority of the 228 compounds have Tc smaller than 1 K. The distribution has, however, a rather fat tail, allowing us to find a series of systems with considerably higher transition temperatures, reaching more than 15 K. In fact, we find 16 compounds with Tc higher than 5 K, including antiperovskites with Y = H, N, C, and O.

(a) A histogram of the calculated values of the electron-phonon coupling constant λ; (b) a histogram of the averaged phonon frequency ωlog; and (c) a histogram of the superconducting transition temperature Tc. The blue curves are for systems with distances to the hull below 50 meV/atom and the orange curves for systems between 50 and 400 meV/atom predicted to have high values of the transition temperature.

The five materials with the highest Tc are listed in the top panel of Table 2, while the complete list can be found in the Supplementary Information. All these materials have positive, but small, distances to the convex hull. While they are not the ones with the highest values of λ, they are the ones that exhibit the best compromise between λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\). The first entry on the list with a predicted Tc of 16.9 K is a nitride, specifically MoNMn3. We could not find any reference to this compound in the literature, and the only known material in the ternary phase diagram is MnMoN234. We then find three hydride antiperovskites, AsHTi3, VHRu3, and PtHCr3 with transition temperatures around 10 K. We could not find any reference to these compounds in the literature either, which is perhaps not surprising as the scientific interest in these materials is rather recent29. In fact, in the ICSD35 database, we only find two such systems with a perovskite structure, namely TlHPd336 and SnHMn337. Finally, we find an oxygen-containing perovskite, HgOZr3, with a Tc of 8.8 K. Once again, no compound in the Hg–O–Zr ternary phase diagram could be found in the ICSD35.

Machine learning

We used the results obtained in the previous section to train two machine-learning algorithms. We note that the size of the data, albeit substantial when compared to the number of electron–phonon calculations present in the literature, is relatively small for most machine-learning algorithms. Therefore, we chose two different machine-learning algorithms that are known to yield good results in such small data sets, specifically, the sure independence screening and sparsifying operator (SISSO)38,39 and the model agnostic supervised local explanations (MAPLE)40. Another distinct advantage of these two models is that they provide straightforward ways to rationalize and interpret complex data that in some way goes well beyond simple statistical tools.

For each composition XYZ3, we used as input features the structure volume (V), the charges of the atoms (QΛ, where Λ ∈ {X, Y, Z}) and the density-of-states at the Fermi level (DOS(EF)), all obtained from the ground-state calculations31. In addition, we included a series of atomic properties: the row (RowΛ) and column (ColΛ) in the periodic table, the electronegativity (χΛ), the atomic weight (MΛ) and its square-root and the covalent radius (RΛ). We chose as target properties λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\).

Due to the relatively small size of the dataset, we decided to use cross-validation: The dataset was randomly split into a training (80%) and a validation set (20%) ten times. We then trained ten machine-learning models on each of the ten training sets. The mean of the errors on the corresponding validation sets is then the cross-validation error.

SISSO

The first model was trained using SISSO38,39. SISSO combines symbolic regression with compressed sensing. Symbolic regression has the advantage of being easily interpretable as the models are simple formulas connecting the features to λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\).

For λ, the training of the model yielded the formula

in five out of the ten different runs. All runs combined have a mean absolute cross-validation error of 0.12. From this formula, we learn that the electron–phonon coupling constant is essentially proportional to the density-of-states at the Fermi level. This is not surprising, as this quantity determines the number of electrons available to form Cooper pairs. We are therefore tempted to look for materials with a very large DOS(EF) in order to maximize Tc. We should however remember that a large density-of-states at the Fermi level often leads to dynamical instabilities related to Jahn–Teller distortions41. We also discover that λ is inversely proportional to the mass of the Y-atom, which favors antiperovskites containing H. Indeed, as we can see from Table 2, most materials with high Tc are of this kind. Finally, the difference in electronegativity will be largest for materials containing O.

The most common formula for \({\omega }_{\log }\), which also appeared in five out of ten runs reads

Unfortunately, in all five cases, the value of c1 turned out to be negative, allowing for negative \({\omega }_{\log }\), and making the interpretation difficult. The second most common formula, which appeared in three out ten runs, gives therefore a more physical description

Independent from the specific formula, the mean absolute cross-validation error for \({\omega }_{\log }\) is 36.5 cm−1. It is clear that the maximum phonon frequency usually depends on the mass of the Y-atom, which is in most cases the lightest in our systems. However, we see that \({\omega }_{\log }\) depends mainly on the properties of the Z-atom, and is inversely proportional to its mass. This means that it is the vibration of the Z-atoms (i.e., of the vertices of the octahedra) and not of the Y-atom that couple strongly with the electrons at the Fermi energy. In addition, Eq. (2) shows that large unit-cell volumes lead to small \({\omega }_{\log }\), and are therefore detrimental to superconductivity.

MAPLE

For the second model we used MAPLE40, a method capable of accurate predictions, while also providing some form of interpretability. Random forests provide an importance score for each feature, which gives a first explanation of global behavior, and weight the training points. Only certain features are used for the prediction by fitting a local linear model using the weights of the provided samples.

Training the model to predict λ yields an error of 0.11, very similar to the one given by SISSO. The five most important features for MAPLE are DOS(EF), QY, ColZ, QZ, and QX. We can see that both models consider the density-of-states to be an essential feature for λ and the properties of the Y- and Z-atom also seem important. As the charge and the electronegativity are connected, the models are probably very similar especially considering the nearly identical error.

Compared to the SISSO model, MAPLE performs only slightly better for \({\omega }_{\log }\) with an error of 31.4 cm−1. The five most important features according to MAPLE are RZ, \(\sqrt{{M}_{Z}}\), χZ, RowZ, and volume of the unit-cell V, in very good agreement with formulas (2) and (3).

Predictions

These models were used to predict the superconducting properties of antiperovskite materials with distances to the hull smaller than 400 meV/atom. By extending our search, we can obtain a much better overview of superconductivity in antiperovskite systems, and estimate the maximum Tc that we might expect in this family. Moreover, (i) the error in the calculation of formation energies with the PBE is considerably larger than 50 meV/atom42,43,44; (ii) often one can synthesize unstable compounds by using targeted synthesis techniques; (iii) there may be further stabilizing (or destabilizing) effects (such as off-stoichiometry, phonons, temperature, doping, etc.

Vibrations can stabilize certain crystalline phases with respect to other45, and the phonon contribution to the free energy can be considerably larger than 50 meV/atom46,47,48,49,50 (although energy differences are smaller, of the order of 10–20 meV/atom). For perovskites also distortions, such as the tilting or rotations of the octahedra, can lower their energy by more than 100 meV/atom51,52. Furthermore, defects can play a major role49,50. In fact, in some cases, such as in the photovoltaic absorbing materials copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) and copper zinc tin sulfide (CZTS), the concentration of defects (in this example, copper vacancies) may amount to more than 10%53, due to their strong stabilizing effect.

By extending the range to 400 meV/atom, we are reasonably sure to cover the cases where the system can be realized experimentally. However, we should keep in mind that the probability of being able to synthesize a compound decreases rapidly with its distance to the convex hull.

In view of a large number of systems in our energy range, we decided to study in detail only the materials for which the machine-learning models predicted large values for Tc. We followed two strategies.

First, in “Machine learning”, we realize the importance of the Z-atom for superconductivity, with lighter atoms leading to higher \({\omega }_{\log }\). Therefore, we investigated all materials of the type XY{Li, Be}3. There are 79 compounds below 400 meV/atom containing Li3 and 16 containing Be3, of which 31 and 7 are dynamically stable, and 8 and 5 exhibit Tc > 5 K, respectively. The five compounds with the highest Tc are listed in the middle panel of Table 2. The two best materials are {Pt, Pd}HBe3 with transition temperatures above 17 K, followed by CoHBe3.

Second, we selected all systems for which both models predicted a Tc of 5 K or higher. Excluding the Be/Li3 compounds there are 248 such materials, of which 167 exhibited imaginary phonon frequencies and 16 failed to converge. Such a high number of dynamically unstable systems is not surprising. In fact, it is clear that the machine-learning models are giving preference to compounds with a large density-of- states at the Fermi surface, particularly prone to structural distortions. From the 65 dynamically stable entries, we found 44 with a transition temperature above 5 K. Surprisingly all of these had Y = H. The top five are listed in the bottom panel of Table 2, and are OsHCr3, IrHCr3, TiHZr3, TiHRu3, and YHZr3, with Tc reaching more than 15 K.

The distributions of values of λ, \({\omega }_{\log }\), and Tc for these materials with a distance to the hull between 50 and 400 meV/atom can be seen as orange lines in Fig. 1. The models clearly predict systems with values of λ higher than the initial dataset (in blue). The distribution of \({\omega }_{\log }\) is however red-shifted, which we can understand from the fact that \({\omega }_{\log }\) is anti-correlated with λ. Finally, from panel c of the picture, we can see the quality of the machine-learning prediction of Tc, with only 21 false negatives out of the 65 compounds.

Specific systems

We start our discussion of the specific systems by comparing the previously studied compounds listed in Table 1 with our calculations with both the LDA and PBE functionals. This comparison will also allow us to identify eventual problems with our methodology that might appear for some compounds. We then discuss in more detail a few materials, which will allow us to better understand superconductivity in inverted perovskites.

Previously studied compounds

There are a few general conclusions that we can draw from Table 1. First, there are a considerable number of systems for which we obtain imaginary phonon frequencies while experiments yields a stable superconductor. Second, for systems with real phonons, there is a very good agreement between the LDA and PBE results, and also between experiment and theory. Third, our results are not always in agreement with other published theoretical results. To understand these, we have to look in detail into each material.

For MgCNi3, the first inverted perovskite superconductor to be discovered16, the existence of imaginary frequencies turns out to be well known54,55. In fact, already in 2003, Ignatov, Savrasov, and Tyson noted the presence of an unstable acoustic mode54, corresponding to perpendicular movements of two Ni atoms towards octahedral interstitials of the perovskite structure. Furthermore, they found that this mode is stabilized by anharmonic effects, that when included in the analysis lead to a very high calculated λ = 1.5154. To make this result compatible with the experimental transition temperature of 8 K required the authors to use the very large μ* = 0.33. We do find imaginary frequencies in our LDA calculation. However, for the PBE the system is dynamically stable, yielding a Tc very close to the experimental value (with a standard μ* = 0.1). It is easy to understand this result by looking at the phonon dispersion. In fact, we find a very soft phonon mode in the PBE that becomes imaginary with the LDA. This is therefore a system that is very close to a phase transition, where small changes in the calculation parameters (in the functional, or even in the pseudopotential) can have a large influence in the results. By this, we do not mean that anharmonic effects are absent from MgCNi3, but that a full understanding of superconductivity in these compounds will require the inclusion of all these effects.

We believe that the same reasons can easily explain the discrepancy between our calculations and experiment for the other systems (such as AlCNi3 or GaNNi3), and we should therefore keep in mind when analyzing the data that a fraction of the systems we labeled unstable can indeed be stable and superconducting.

In what concerns SrPPt3 and CaPPt3, the experimental structures56 are not cubic and are more complex than the five-atom cell used in this work. Therefore, it is not surprising that we find large imaginary phonons frequencies across the whole Brillouin zone for these compounds, indicating that our simple cell is extremely unstable.

For other compounds where we obtained real phonons, we can see a good agreement between calculation and experiment. This is the case of CdCNi3, InNNi3, YBRh3, and InCY3. For InCNi3, we obtain a non-magnetic superconductor, while ref. 57 finds a magnetic system. However, as discussed in that work, the magnetism is suggested to originate from the deviation of the Ni/In atomic ratio from the ideal stoichiometry (the experimental sample contained 5% of In vacancies). Finally, for SnOSr3 we find a normal metal, while ref. 58 obtained a superconductor. However, batch ”E” in the experimental article, that was believed to have approximately stoichiometric composition, showed semiconducting resistivity behavior down to low temperature. Superconductivity seems therefore to be closely related to the doping caused by Sr deficiency, that is absent from our calculations.

Let us now discuss the materials that were predicted previously to be superconductive theoretically. The agreement is very good for ZnNNi3, GaNCr3. For RhNCr3, we obtain a magnetic ground state, while ref. 19 apparently performed calculations for an incorrect spin-compensated state. Then, it appears that calculations in the literature for SnOSr3, AlBSc3, GaBSc3, InBSc3, and TlBSc3 using the Gaspari–Gyorffy formula59 tend to grossly exaggerate the superconducting transition temperature, and even to yield erroneous trends.

PtHBe3

This material exhibited the highest transition temperature for all stoichiometries studied. This is a hypothetical material, and as we see from Table 2 its distance to the convex hull of stability amounts to 175 meV/atom. From the electronic band structure depicted in Fig. 2, we can see that the valence is dominated by highly delocalized electrons, leading to very dispersing bands with a bandwidth of around 4 eV. As a consequence, the density-of-states at the Fermi surface is not particularly large.

The phonon band structure, density-of-states, and α2F(ω) can be seen in Fig. 3. As the masses of H, Be, and Pt are very different, the phonon modes completely decouple: The highest phonon optical modes between 800 and 1100 cm−1 are vibrations of H; The nine optical modes between 200 and 600 cm−1 are almost exclusively composed of the Be at the vertices of the octahedra; Finally, the acoustic modes are due to Pt vibrations. The latter modes are the ones that couple more strongly with the electrons, but there is still a sizeable contribution from the H and Be modes. This leads to \({\omega }_{\log }=208\) cm−1 and λ = 1.0 calculated with a 8 × 8 × 8 q-point grid, and Tc = 15.4 K.

We also investigated the behavior of the superconducting properties with pressure. As expected, the average frequency \({\omega }_{\log }\) increases monotonically with pressure, although saturating at high pressures. The inverse happens for λ that decreases exponentially with increasing pressure. This leads to a transition temperature that decreases monotonically with pressure, at least for the range we investigated (from 0 to 50 GPa).

ScCRh3

The family of transition metal carbides, to which ScCRh3 belongs to, has attracted some attention due to high stability and hardness. It is therefore not surprising that the structural, electronic and elastic properties of this compound have already been studied in the literature60,61,62. The electronic band structure and corresponding density-of-states can be seen in Fig. 4. It turns out that ScCRh3 is a metal with highly dispersive bands crossing the Fermi energy around the R point. However, parabolic valence and conduction bands barely touch at Γ, leading to a relatively small density-of-states at the Fermi level.

The phonon band structure, density-of-states, and α2F(ω) can be seen in Fig. 5. As expected due to the mass difference, the highest energy optical phonons correspond to vibrations of the carbon atoms that occupy the center of the octahedra. These are very dispersive bands that yield a small density-of-states and that do not couple strongly with the electrons. At around 200 cm−1 we find the vibrations of the Sc atoms. These are very localized bands resulting in a large peak in the density-of-states that however couple weakly to the electrons. The largest contribution to λ comes indeed from the vibrations of the Rh atoms forming the octahedra, in particular the acoustic modes and lowest-lying optical modes. It is therefore not surprising that \({\omega }_{\log }\) has the relatively modest value of 177 cm−1 and λ = 0.64, leading to Tc = 5.0 K. However, looking at the electronic density-of-states, we can expect that hole-doping this compound should increase considerably the density-of-states at the Fermi level and the superconducting transition temperature.

As expected, \({\omega }_{\log }\) increases monotonically with increasing pressure, although in a sublinear way. The behavior of λ is more complicated, with a minimum at around 28 GPa. Assuming a constant μ*, we then obtain that Tc decreases with increasing pressure until around 15 GPa, and then increases reaching around 5.4 K at ~ 55 GPa.

MoNMn3

MoNMn3 was the material with the highest superconducting transition temperature that appeared in our systematic high-throughput search. This is a hypothetical compound, appearing 66 meV/atom above the updated convex hull. From the band structure and electronic density-of-states depicted in Fig. 6, we can see several bands crossing the Fermi level, leading to a complex Fermi surface with a pocket around the R point and several bands barely touching the Fermi level at X, M, and between Γ and R. Looking at the phonon band structure (see Fig. 7), we can see that the low-lying bands have contributions from both cations, and are followed by two bands involving purely Mn vibrations. Finally, there is a gap, and we find (as expected from the considerable difference of masses), the phonons involving the N atoms. Although all modes contribute to some extent to λ, the strong contributions to the electron–phonon coupling constant come from the modes between around 150–300 cm−1.

Considering the behavior of MoNMn3 with pressure, we find that as expected \({\omega }_{\log }\) increases and λ decreases. This leads to an overall small decrease of the superconducting transition temperature with the pressure of the order of 0.13 K/GPa.

AsHTi3

Our final example is AsHTi3. The band structure for this compound is shown in Fig. 8. We can see that close to the X-point, and in the line connecting the M and Γ point, there are bands with relatively flat regions, translating to a rather large density-of-states at the Fermi level. We might expect that this benefits superconductivity, but as we know it also unlocks Jahn–Teller distortions41. This can be clearly seen in the phonon band structure depicted in Fig. 9. Once again, the H-modes are very high in energy and completely separated from the other bands and do not couple with the electrons. All other bands involving Ti and As states couple strongly with the electrons leading to \({\omega }_{\log }=170\) cm−1 and a rather high λ = 0.94. One can also see that the lowest acoustic mode is very soft, especially in the line connecting the M and the Γ point, and has a massive coupling with the electrons. This is an indication that the system is therefore very close to a structural phase transition. This situation is of course not unique, and we found several systems with relatively large Tc and with very soft modes. As we mentioned above, these modes are often related to distortions of the octahedra typical of perovskites. Note that, although the existence of these soft modes can increase substantially λ, it also makes \({\omega }_{\log }\) smaller, so the effect on Tc may be less relevant than expected.

When pressure is applied, λ increases and \({\omega }_{\log }\) decreases due to the softening of a phonon mode. This mode becomes imaginary above 30 GPa, indicating a pressure-induced structural transition. Again the behavior of Tc is complex, increasing to 11.2 K at 20 GPa, but then decreasing until the onset of the transition.

Discussion

We presented an extensive study of superconductivity in inverted perovskite compounds with composition XYZ3 where Y is a nonmetal and X and Z are metals. We started by using density-functional perturbation theory to calculate both \({\omega }_{\log }\) and α2F(ω) for 397 thermodynamically stable (or close to it) materials. Most of the dynamically stable compounds turned out to have an electron–phonon coupling constant λ below 0.5 and \({\omega }_{\log }\) between 150 and 400 cm−1. As such, only a few have superconducting transition temperatures larger than a few Kelvin, and as few as 16 inverted perovskites appear with a Tc larger than 5 K.

These data were then used to train two machine-learning models. Our objective was twofold: (i) first to understand and interpret the superconducting properties based on the chemical composition of the material and simple ground-state properties and (ii) to develop simple statistical models that are capable of predicting λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\) (and therefore Tc) for arbitrary inverted perovskites. The picture that emerged is that λ is directly proportional to the density-of-states at the Fermi surface and inversely proportional to the mass of the Y-atom, while \({\omega }_{\log }\) is mostly determined by the Z-atom. Based on the understanding gained from the models and the actual predictions, we found a further 55 (thermodynamically unstable) materials with a (validated) transition temperature above 5 K, reaching a maximum of 17.8 K for PtHBe3.

By comparing our results with published experimental and theoretical studies we arrived at the following conclusions: (i) in the few cases where a direct comparison was possible, density-functional perturbation theory compared quite well with the experiment; furthermore, values of Tc seem to be rather insensitive to the choice of the exchange-correlation functional; (ii) Off-stoichiometry in experimental samples can have strong effects in the properties of the material by, e.g., rendering it magnetic or even superconducting. (iii) Anharmonic effects are definitively important in stabilizing some phases; however, it is also likely that some of the effects previously attributed to anharmonicity are actually related to an insufficient description of the electronic exchange-correlation functional. (iv) Estimates of Tc based on the Gaspari–Gyorffy formula seem to be highly overestimated for inverted perovskites.

Finally, we studied the electronic and phononic properties of a few materials in more detail. Combining this with our previous machine-learning models, we could get a more comprehensive picture of the mechanism of superconductivity in inverted perovskites. The phonon modes that couple more strongly with the electrons, and that are responsible for the binding of the Cooper pairs, are related to vibrations of the Z-atoms that form the octahedra characteristic of perovskites. These modes are rather soft, which enhances the electron–phonon coupling constant λ but leads to small values of \({\omega }_{\log }\). For some materials, however, the soft modes become imaginary and the system is dynamically unstable, deforming by the tilting or rotation of the octahedra. To reach values of Tc above 5 K thus requires a careful balance, so that the crystal is close, but not too close to structural instability.

In conclusion, we showed how the combination of traditional approaches, based on density-functional theory, and interpretable machine-learning models can give us not only quantitative predictions of superconducting properties, but also a qualitative interpretation of the mechanism of superconduction. Furthermore, these systematic approaches provide a very different perspective, allowing us to infer the behavior of whole classes of materials, and to distinguish standard compounds from outliers with exceptional properties. As such, we expect that they will become more common in the near future.

Methods

Crystal structures

The cubic antiperovskite unit-cell belongs to the space group \(Pm\bar{3}m\) (#221), and contains five atoms in the primitive unit. For simplicity, we will always label our systems as XYZ3, where the X atoms are in Wyckoff position 1a (at the center of the cubes), the Y in the position 1b (at the center of the octahedra), and finally the Z-atoms are in the position 3c (at the vertices of the ocahedra) (see Fig. 10).

Convex hull

In ref. 31, we used the convex hull of the Materials Project63. Since then, the knowledge of the convex hull improved massively. Consequently, we reevaluated the distances to the convex hull using the rather complete dataset from ref. 64. Furthermore, and due to the errors associated with PBE formation energies43 we decided to recalculate the selected systems with the approach and calculation parameters from ref. 65. This allows us to evaluate the distance to the convex hull with the PBEsol66 and SCAN functionals44. The former reduces the error of the PBE for lattice constants67 considerably, while the latter was shown to have a superior performance for determining thermodynamic stability68. The resulting PBE, PBEsol, and SCAN distances to the convex hull can be found in the Supplementary Material for all materials considered. In most cases, we do not see a large difference between the three values, with one notable exception. For materials where the Z-atom is a 3d transition metal, SCAN distances to the hull are sometimes hundreds of meV/atom larger than their PBE or PBEsol counterparts. This is due to the well-known problem of SCAN for itinerant magnets, leading to a significant overestimation of the magnetic moments69. In such cases, the PBE (or PBEsol) values are expected to be significantly more accurate than SCAN.

Electron–phonon calculations

We performed electron–phonon calculations using QUANTUM ESPRESSO version 6.8. We used pseudopotentials from the PSEUDODOJO project33, specifically the stringent norm-conserving set. This pseudopotential table has been systematically constructed and validated in a series of 7 tests in crystalline environments, specifically the Δ-Gauge70, \({{\Delta }}^{\prime}\)-Gauge71, GBRV-FCC, GBRV-BCC, GBRV-compound72, ghost-state detection, and phonons at the Γ-point. We note that PSEUDODOJO does not include an LDA pseudopotential for La, but provides a PBE one. Therefore, and for consistency, we did not use any compounds including La in our training set, but evaluated a posteriori the electron–phonon and superconducting properties of all relevant La-including antiperovskites using the PBE functional.

For the calculation of the superconducting properties, we used the Perdew–Wang73 local-density approximation. Our choice was based on the fact that the local-density approximation performs surprisingly well when compared, for example, to several commonly used generalized gradient approximations74, and is more stable numerically. In any case, to understand the dependence on the results with the functional, we also used the PBE functional32 for a few compounds.

Our workflow consisted in the following steps:

-

(i)

The energy cutoff was automatically determined such that the total energy was converged to 2.5 meV/atom. This led to cutoffs in the interval 60–150 Ry, with the large majority of the compounds laying in the interval 80–100 Ry. We tested these parameters by performing calculations for three systems using the more stringent condition that the total energy was converged to 1.0 meV/atom. Values for λ changed by a maximum of 0.005 and \({\omega }_{\log }\) by 6 cm−1 leading to an insignificant variation of Tc (smaller than 0.1 K).

-

(ii)

The lattice constant was optimized using a Γ-centered 8 × 8 × 8 k-point grid until the energy was converged to 10−5 a.u. and the pressure to 0.5 kbar. For the electron–phonon coupling we used the same k-point grid. We tried to increase it to a 12 × 12 × 12 but it only led to small changes in Tc.

-

(iii)

For the q-sampling of the phonons, we used a regular 4 × 4 × 4 grid, in line with previous theoretical works on inverted perovskites75,76. We tested the quality of the sampling by performing calculations with a denser 8 × 8 × 8 q-point grid. For example, for PtHBe3 a 4 × 4 × 4 (8 × 8 × 8) sampling leads to λ = 1.25 (1.04), \({\omega }_{\log }=190\) cm−1 (208 cm−1) and Tc = 17.8 K (15.4 K). For YHZr3, we have λ = 1.15 (1.13), \({\omega }_{\log }=137\) cm−1 (140 cm−1) and Tc = 11.6 K (11.6 K). Finally, for AsHTi3, we obtain λ = 0.95 (0.94), \({\omega }_{\log }=162\) cm−1 (170 cm−1) and Tc = 10.4 K (10.7 K). The differences in λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\) are sometimes not negligible, but they mostly cancel out in the calculation of Tc. In any case, the incertitude in Tc due to q-point sampling is smaller than the one of other parameters (such as μ*) and is adequate enough for our purposes during the high-throughput search. The detailed discussion of specific materials will be done, instead, using the denser 8 × 8 × 8 sampling.

-

(iv)

The double δ-integration to obtain the Eliashberg function was performed with a Methfessel–Paxton smearing of 0.05 Ry. For the 8 × 8 × 8, we found that the integrated values were essentially constant for smearings in the range 0.02–0.05 Ry, but varied more for the coarser q-grid. We chose the value of 0.05 Ry for the high-throughput study, as it yielded the best integrated values of λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\) when compared to the better converged 8 × 8 × 8 results.

-

(v)

The values of λ and \({\omega }_{\log }\) were then used to calculate the superconducting transition temperature using the Allen–Dynes modification77 to the McMillan formula78

$${T}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}=\frac{{w}_{\log }}{1.20}\exp \left[-1.04\frac{1+\lambda }{\lambda -{\mu }^{* }(1+0.62\lambda )}\right].$$(4)We took arbitrarily the value of μ* = 0.10 for all materials studied.

SISSO hyperparameters

For the training of the SISSO models, we considered a descriptor of dimension 1, a feature space of rung 2 with a maximum feature complexity of 10 and a subspace size of 20. The following operators were used to construct the formulas: \(+,\,-,\,* ,\,/,\,\exp ,\,\exp -,\,\wedge -1,\,\wedge 2,\,\wedge 3,\,\wedge 6,\,{{{\rm{sqrt}}}},\,{{{\rm{cbrt}}}},\,\log ,\,{{{\rm{abs}}}}\). The features had an absolute data value range of 0.001 up to 100,000. The 23 input features were grouped in the following dimension (unit) classes: (1) the structure volume, (2) the atom charges, (3) the density-of-states, (4) the columns, and (5) the rows in the periodic table, (6) the electronegativities, (7) the atomic weights, (8) the square roots of the atomic weights, and (9) the covalent radii. The sparsifying operator L0 was used together with the RMSE metric.

MAPLE hyperparameters

The MAPLE model used a random forest regressor with 200 trees and a minimum number of 10 samples per leaf. Furthermore, 50% of the features were considered looking for the best split. The local linear model had a regularization of 0.001. For the rest of the parameters, we used the default values in the MAPLE implementation (https://github.com/GDPlumb/MAPLE.git).

Data availability

All data used in or resulting from this work is available in the manuscript, the Supplementary Material and at https://archive.materialscloud.org/record/2022.49.

Code availability

Code for the MAPLE model is provided at https://github.com/hyllios/utils. The code for the SISSO models can be found in the original repository.

References

Mitchell, R. H. Perovskites: Modern and Ancient (Almaz Press Thunder Bay, 2002).

Liu, M., Johnston, M. B. & Snaith, H. J. Efficient planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by vapour deposition. Nature 501, 395 (2013).

Stranks, S. D. & Snaith, H. J. Metal-halide perovskites for photovoltaic and light-emitting devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 391 (2015).

Schileo, G. & Grancini, G. Halide perovskites: current issues and new strategies to push material and device stability. J. Phys. Energy 2, 021005 (2020).

deQuilettes, D. W. et al. Charge-carrier recombination in halide perovskites. Chem. Rev. 119, 11007 (2019).

Uchino, K. Glory of piezoelectric perovskites. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 16, 046001 (2015).

Kundu, A. K. Magnetic Perovskites: Synthesis, Structure and Physical Properties (Springer India, 2016).

Okuda, T., Nakanishi, K., Miyasaka, S. & Tokura, Y. Large thermoelectric response of metallic perovskites: Sr1−xLaxTiO3(0 ≲ x ≲ 0.1). Phys. Rev. B 63, 113104 (2001).

Deschler, F. et al. High photoluminescence efficiency and optically pumped lasing in solution-processed mixed halide perovskite semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1421 (2014).

Xing, G. et al. Low-temperature solution-processed wavelength-tunable perovskites for lasing. Nat. Mater. 13, 476 (2014).

Liu, H. & Yang, X. A brief review on perovskite multiferroics. Ferroelectrics 507, 69 (2017).

Bednorz, J. G. & Müller, K. A. Perovskite-type oxides—the new approach to high-Tc superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 60, 585 (1988).

Wollman, D. A., Van Harlingen, D. J., Lee, W. C., Ginsberg, D. M. & Leggett, A. J. Experimental determination of the superconducting pairing state in YBCO from the phase coherence of YBCO-Pb dc SQUIDs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 2134 (1993).

Monthoux, P., Balatsky, A. V. & Pines, D. Toward a theory of high-temperature superconductivity in the antiferromagnetically correlated cuprate oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 3448 (1991).

Scalapino, D. J., Loh, E. & Hirsch, J. E. d-wave pairing near a spin-density-wave instability. Phys. Rev. B 34, 8190 (1986).

He, T. et al. Superconductivity in the non-oxide perovskite MgCNi3. Nature 411, 54 (2001).

Lin, J.-Y. & Yang, H. MgCNi3: a conventional and yet puzzling superconductor. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0308198 (2003).

Zhao, J.-T., Dong, Z.-C., Vaughey, J., Ostenson, J. E. & Corbett, J. D. Synthesis, structures and properties of cubic R3In and R3InZ phases (R = Y, La; Z = B, C, N, O): the effect of interstitial Z on the superconductivity of La3In. J. Alloy. Compd. 230, 1 (1995).

Tütüncü, H. M. & Srivastava, G. P. Theoretical examination of superconductivity in the cubic antiperovskite Cr3GaN under pressure. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 053905 (2013).

Wiendlocha, B., Tobola, J. & Kaprzyk, S. Search for Sc3XB (X=In, Tl, Ga, Al) perovskites superconductors and proximity of weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 73, 134522 (2006).

Sarmiento-Pérez, R., Cerqueira, T. F. T., Körbel, S., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Prediction of stable nitride perovskites. Chem. Mater. 27, 5957 (2015).

Flores-Livas, J. A., Sarmiento-Pérez, R., Botti, S., Goedecker, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Rare-earth magnetic nitride perovskites. J. Phys. Mater. 2, 025003 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Antiperovskites with exceptional functionalities. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905007 (2020).

Schaak, R. et al. Formation of transition metal boride and carbide perovskites related to superconducting MgCNi3. J. Solid State Chem. 177, 1244 (2004).

Mao, Z. Q. et al. Experimental determination of superconducting parameters for the intermetallic perovskite superconductor MgCNi3. Phys. Rev. B 67, 094502 (2003).

García, J., Bartolomé, J., González, D., Navarro, R. & Fruchart, D. Thermophysical properties of intermetallic Mn3MC perovskites i. heat capacity of manganese gallium carbide Mn3GaC. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 15, 1059 (1983).

Kaneko, T., Kanomata, T. & Shirakawa, K. Pressure effect on the magnetic transition temperatures in the intermetallic compounds Mn3MC (M=Ga, Zn and Sn). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 56, 4047 (1987).

Connétable, D. & Maugis, P. First principle calculations of the κ-Fe3AlC perovskite and iron-aluminium intermetallics. Intermetallics 16, 345 (2008).

Gao, S. et al. Hydride-based antiperovskites with soft anionic sublattices as fast alkali ionic conductors. Nat. Commun. 12, 1 (2021).

Shipley, A. M., Hutcheon, M. J., Needs, R. J. & Pickard, C. J. High-throughput discovery of high-temperature conventional superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 104, 054501 (2021).

Schmidt, J. et al. Predicting the thermodynamic stability of solids combining density functional theory and machine learning. Chem. Mater. 29, 5090 (2017).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

van Setten, M. et al. The pseudodojo: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Comm. 226, 39 (2018).

Bem, D. S., Lampe-Önnerud, C. M., Olsen, H. P. & zur Loye, H.-C. Synthesis and structure of two new ternary nitrides: FeWN2 and MnMoN2. Inorg. Chem. 35, 581 (1996).

Bergerhoff, G., Allen, F. H. & Sievers, R. (eds) Crystallographic Databases (International Union of Crystallography, Chester, 1987).

Kurtzemann, N. & Kohlmann, H. Crystal structure and formation of TlPd3 and its new hydride TlPd3h. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 636, 1032 (2010).

Grosse, G., Wagner, F., Antonov, V. & Antonova, T. 119Sn Mössbauer study of Mn3SnHx. J. Alloy. Compd. 253-254, 339 (1997).

Ouyang, R., Ahmetcik, E., Carbogno, C., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. M. Simultaneous learning of several materials properties from incomplete databases with multi-task SISSO. J. Phys. Mater. 2, 024002 (2019).

Ouyang, R., Curtarolo, S., Ahmetcik, E., Scheffler, M. & Ghiringhelli, L. M. Sisso: a compressed-sensing method for identifying the best low-dimensional descriptor in an immensity of offered candidates. Phys Rev. Mater. 2, 083802 (2018).

Plumb, G., Molitor, D. & Talwalkar, A. S. Model agnostic supervised local explanations. Adv. Neural Inf. Processing Syst. 31, 2515–2524 (2018).

O’Brien, M. C. M. & Chancey, C. C. The Jahn–Teller effect: an introduction and current review. Am. J. Phys. 61, 688 (1993).

Stevanović, V., Lany, S., Zhang, X. & Zunger, A. Correcting density functional theory for accurate predictions of compound enthalpies of formation: fitted elemental-phase reference energies. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115104 (2012).

Sarmiento-Pérez, R., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Optimized exchange and correlation semilocal functional for the calculation of energies of formation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3844 (2015).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Huan, T. D. et al. Low-energy polymeric phases of alanates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 135502 (2013).

Sorella, S., Casula, M., Spanu, L. & Dal Corso, A. Ab initio calculations for the β-tin diamond transition in silicon: comparing theories with experiments. Phys. Rev. B 83, 075119 (2011).

Grochala, W. Diamond: electronic ground state of carbon at temperatures approaching 0 k. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3680 (2014).

Widom, M. & Mihalkovič, M. Symmetry-broken crystal structure of elemental boron at low temperature. Phys. Rev. B 77, 064113 (2008).

Ogitsu, T. et al. Imperfect crystal and unusual semiconductor: boron, a frustrated element. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1903 (2009).

van Setten, M. J., Uijttewaal, M. A., de Wijs, G. A. & de Groot, R. A. Thermodynamic stability of boron: the role of defects and zero point motion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2458 (2007).

Wang, H.-C., Schmidt, J., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. A high-throughput study of oxynitride, oxyfluoride and nitrofluoride perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 8501 (2021).

Brivio, F., Caetano, C. & Walsh, A. Thermodynamic origin of photoinstability in the ch3nh3pb(i1-xbrx)3 hybrid halide perovskite alloy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1083 (2016).

Sheu, H.-H., Hsu, Y.-T., Jian, S.-Y. & Liang, S.-C. The effect of Cu concentration in the photovoltaic efficiency of CIGS solar cells prepared by co-evaporation technique. Vacuum 131, 278 (2016).

Ignatov, A. Y., Savrasov, S. Y. & Tyson, T. A. Superconductivity near the vibrational-mode instability in MgCNi3. Phys. Rev. B 68, 220504 (2003).

Cui, Y. et al. Theoretical investigation on thermodynamics and stability of anti-perovskite MgCNi3 superconductor. Chem. Phys. Lett. 780, 138961 (2021).

Takayama, T. et al. Strong coupling superconductivity at 8.4 k in an antiperovskite phosphide SrPt3P. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 237001 (2012).

Tong, P., Sun, Y., Zhu, X. & Song, W. Synthesis and physical properties of antiperovskite-type compound In0.95CNi3. Solid State Commun. 141, 336 (2007).

Oudah, M. et al. Superconductivity in the antiperovskite dirac-metal oxide Sr3−xSnO. Nat. Commun. 7, 1 (2016).

Gaspari, G. D. & Gyorffy, B. L. Electron-phonon interactions, d resonances, and superconductivity in transition metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 801 (1972).

Sahara, R. et al. First-principles study of the structural, electronic, and elastic properties of RRh3BxC1−x (R = Sc and Y). Phys. Rev. B 76, 024105 (2007).

Kojima, H. et al. Ab initio studies of structural, elastic, and electronic properties of RRh3BX (R = Sc, Y, La, and Ce). Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 081901 (2007).

Bouhemadou, A. Elastic properties of mono- and polycrystalline RCRh3, (R = Sc, Y, La and Lu) under pressure effect. Solid State Commun. 149, 1658 (2009).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: the materials project: a materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002 (2013).

Schmidt, J., Pettersson, L., Verdozzi, C., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Crystal graph attention networks for the prediction of stable materials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7948 (2021).

Schmidt, J., Wang, H.-C., Cerqueira, T. F. T., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. A dataset of 175k stable and metastable materials calculated with the PBEsol and SCAN functionals. Sci. Data 9, 64 (2022).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Hussein, R., Schmidt, J., Barros, T., Marques, M. A. & Botti, S. Machine-learning correction to density-functional crystal structure optimization. MRS Bulletin 1, (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Efficient first-principles prediction of solid stability: towards chemical accuracy. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 1 (2018).

Ekholm, M. et al. Assessing the scan functional for itinerant electron ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 98, 094413 (2018).

Lejaeghere, K., Speybroeck, V. V., Oost, G. V. & Cottenier, S. Error estimates for solid-state density-functional theory predictions: an overview by means of the ground-state elemental crystals. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 39, 1 (2013).

Jollet, F., Torrent, M. & Holzwarth, N. Generation of projector augmented-wave atomic data: A 71 element validated table in the XML format. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 1246 (2014).

Garrity, K. F., Bennett, J. W., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Pseudopotentials for high-throughput DFT calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 81, 446 (2014).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244 (1992).

He, L. et al. Accuracy of generalized gradient approximation functionals for density-functional perturbation theory calculations. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064305 (2014).

Chen, J.-Y. & Wang, X. First-principles verification of CuNNi3 and ZnNNi3 as phonon mediated superconductors. Chin. Phys. B 24, 086301 (2015).

Ram, S. & Kanchana, V. Lattice dynamics and superconducting properties of antiperovskite La3InZ (Z = N,O). Solid State Commun. 181, 54 (2014).

Allen, P. B. & Dynes, R. C. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B 12, 905 (1975).

McMillan, W. L. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys. Rev. 167, 331 (1968).

Dong, A. et al. Synthesis and physical properties of AlCNi3. Phys. C. Supercond. 422, 65 (2005).

Tong, P., Sun, Y. P., Zhu, X. B. & Song, W. H. Strong spin fluctuations and possible non-fermi-liquid behavior in AlCNi3. Phys. Rev. B 74, 224416 (2006).

Tong, P., Sun, Y. P., Zhu, X. B. & Song, W. H. Strong electron-electron correlation in the antiperovskite compound GaCNi3. Phys. Rev. B 73, 245106 (2006).

Uehara, M., Yamazaki, T., Kôri, T., Kashida, T., Kimishima, Y. & Hase, I. Superconducting properties of CdCNi3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 76, 034714 (2007).

Uehara, M., Uehara, A., Kozawa, K. & Kimishima, Y. New antiperovskite-type superconductor ZnNyNi3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 033702 (2009).

Park, M.-S. et al. Physical properties of ZnCNi3: comparison with superconducting MgCNi3. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 17, 274 (2003).

He, B. et al. CuNNi3: a new nitride superconductor with antiperovskite structure. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 26, 125015 (2013).

Uehara, M., Uehara, A., Kozawa, K., Yamazaki, T. & Kimishima, Y. New antiperovskite superconductor ZnNNi3, and related compounds CdNNi3 and InNNi3. Phys. C. Supercond. 470, S688 (2010).

Tütüncü, H. M. & Srivastava, G. P. Phonons and superconductivity in the cubic perovskite Cr3RhN. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 093914 (2012).

Haque, E. & Hossain, M. A. First-principles study of mechanical, thermodynamic, transport and superconducting properties of Sr3SnO. J. Alloy. Compd. 730, 279 (2018).

Takei, H., Kobayashi, N., Yamauchi, H., Shishido, T. & Fukase, T. Magnetic and superconducting properties of the cubic perovskite YRh3B. J. Less Common Met. 125, 233 (1986).

Holleck, H. Carbon-and boron-stabilized ordered phases of scandium. J. Less-Common Met. 52, 167 (1977).

Nardin, M. et al. Etude de cinq nouveaus nitrures MCr3N de type perovskite. C. R. Seances Acad. Sci., Ser. C. 274, 2168 (1972).

Acknowledgements

T.F.T.C. acknowledges the financial support from the CFisUC through the project UIDB/04564/2020 and the Laboratory for Advanced Computing at the University of Coimbra for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.F.T.C. and M.A.L.M. performed the electron–phonon calculations. N.H. and J.S. trained the machine-learning models. All authors contributed to designing the research, interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, N., Cerqueira, T.F.T., Schmidt, J. et al. Superconductivity in antiperovskites. npj Comput Mater 8, 150 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00817-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00817-4

This article is cited by

-

Closed-loop superconducting materials discovery

npj Computational Materials (2023)

-

Searching for ductile superconducting Heusler X2YZ compounds

npj Computational Materials (2023)