Abstract

In the epitaxial growth of two-dimensional (2D) materials on substrates, 2D polycrystals with various shapes have been broadly observed, but their formation mechanisms are still highly elusive. Here we present a complete study on the formation mechanisms of various 2D polycrystals. The structures of the 2D polycrystals are dependent on the symmetries of both the 2D material and the substrate. We build four complete libraries of 2D polycrystals for (i) threefold symmetric 2D materials on two- or six-fold symmetric substrates (i.e., family-III/II or -III/VI), (ii) threefold symmetric 2D materials on fourfold symmetric substrates (i.e. family-III/IV), (iii) fourfold symmetric 2D materials on three- or six-fold symmetric substrates (i.e., family-IV/III or -IV/VI), and (iv) sixfold symmetric 2D materials on fourfold symmetric substrates (i.e., family-VI/IV), respectively. The four libraries of 2D polycrystals are consistent with many existing experimental observations and can be used to guide the experimental synthesis of various 2D polycrystals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) materials are the most promising materials for future nanodevices, because of their peculiar properties1,2,3,4,5. To realize their practical applications, the controllable synthesis of 2D materials is indispensable. Currently, vapor deposition methods have been widely employed to synthesize various 2D materials, and they were found to be capable of controlling layer number6,7, domain shape8,9, and crystallinity10,11. For the synthesis of a 2D material via vapor deposition on a substrate, controlling its crystallinity is fundamentally important. In most vapor deposition processes for 2D materials growth, multiple nucleations of 2D grains are ubiquitous and thus, the crystallinity of the synthesized 2D material depends on the alignment of 2D grains on a substrate. Our previous study has revealed a general epitaxial relationship of the alignment of a 2D material on a substrate, that the alignment of the 2D material is determined by a high symmetric direction of the 2D material along a high symmetric direction of the substrate. Based on the general relationship of epitaxy, we have concluded that the unidirectionally aligned 2D material’s grains on a substrate can be achieved if the symmetric group of the substrate is a subgroup of that of the 2D material12 or

where GSub and G2D are the symmetric groups of the substrate and the 2D material, respectively, so that wafer-scale single-crystalline (WSSC) 2D materials can be obtained by seamless coalescence of unidirectionally aligned 2D grains. In agreement with this simple principle, experimentally, WSSC sixfold symmetric graphene has been successfully synthesized on the twofold symmetric Ge(110) surface13 and sixfold symmetric Cu(111) surface14,15,16; WSSC threefold symmetric hBN has been recently grown on vicinal Cu(110) and Cu(111) surfaces with step edges17,18; the low symmetric vicinal Au(111) and Al2O3(0001) surfaces have also been employed as substrates to synthesize WSSC single-crystalline MoS219,20 and WS221 very recently.

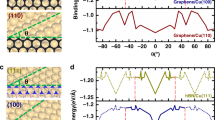

It should be noted that for many cases of 2D materials’ synthesis, Eq. (1) no longer stands and thus multi-orientations of 2D grains on a substrate will be naturally seen. Our theoretical study has revealed that a threefold symmetric 2D material has two equivalent low-energy orientations on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate (Fig. 1a, b), and four equivalent low-energy orientations on a fourfold symmetric substrate (Fig. 1c); a fourfold symmetric 2D material has three equivalent low-energy orientations on a three- or six-fold symmetric substrate (Fig. 1d, e); a sixfold symmetric 2D material has two equivalent low-energy orientations on a fourfold symmetric substrate (Fig. 1f)12. Consequently, various polycrystals of these 2D materials on various substrates will be formed by the coalescence of misaligned 2D grains during their growth.

a–c A threefold symmetric 2D material on a two-, six-, and four-fold symmetric substrate, respectively. d, e A fourfold symmetric 2D material on a three- and six-fold symmetric substrate, respectively. f A sixfold symmetric 2D material on a fourfold symmetric substrate. The 2D materials’ edges that are preferentially aligned to the high symmetric directions of the substrates are highlighted.

Experimentally, triangular hBN grains with two and four orientations were observed on twofold symmetric (110) (and/or sixfold symmetric (111)) surfaces17,22,23,24,25 and fourfold symmetric (100) surfaces22,24,26,27 of face-centered cubic (fcc) substrates, respectively. Triangular transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) grains with two opposite orientations were frequently observed on (0001) surfaces of Al2O328,29,30 and GaN31, of which the top atomic layer has a near sixfold symmetry. Hexagonal graphene grains with a 30o misorientation angle were also broadly observed on Cu(100) surface32. All these observations are consistent with the theoretical predictions.

During further vapor deposition growth of 2D materials, the coalescence of these misaligned islands will form 2D polycrystals. For example, four types of polycrystalline hBN islands, which show both concave and convex corners around their circumferences, have been observed on Cu(110) surfaces25. Polycrystals of the exact same shapes were also seen during hBN growth on Cu(111) surfaces23 and TMDCs growth on sixfold symmetric surfaces28,29,30,31. In addition, more complex polycrystalline hBN islands were formed on fourfold symmetric Cu(100) surfaces22. Up to now, only the formation of polycrystalline TMDC islands from antiparallel grains is illustrated33. The systematic understanding of the formation mechanisms of 2D polycrystals is still illusive, which hinders both our fundamental understanding of 2D material's growth and their applications.

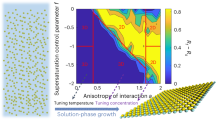

Phase-field theory (PFT) modeling has been employed to investigate 2D crystal growth because of its capability in revealing the kinetic evolution of 2D crystals coupled with precursor concentration distribution at a large scale34. For instance, Lowengrub et al. have used PFT simulations to investigate the effect of anisotropic diffusion of precursors on the morphology evolution of 2D single crystals35 and then further studied the vertical growth of multilayer 2D single crystals36,37. Chen et al. have successfully coupled chemical vapor deposition (CVD) controlling parameters to the PFT model and mainly revealed the effect of precursor concentration and distribution on the coverage, shape evolution, and size of threefold symmetric 2D crystals38,39,40. Yu et al. reported a PFT model to reveal the self-coalescence of a 2D single crystal induced by the curvature of substrate41.

Here, we present a systematic study on the formation mechanism of 2D polycrystals. Based on the alignments of 2D single crystals on a substrate and phase PFT simulations, a general strategy of constructing various 2D polycrystals is proposed. We have built four libraries of 2D polycrystals, which correspond to (i) threefold symmetric 2D materials on a two- or sixfold symmetric substrate, i.e., family-III/II or -III/VI, (ii) threefold symmetric 2D materials on a fourfold symmetric substrate, i.e., family-III/IV, (iii) fourfold symmetric 2D materials on a three- or six-fold symmetric substrate, i.e., family-IV/III or –IV/VI and (iv) sixfold symmetric 2D materials on a twofold symmetric substrate, i.e., family-VI/II, respectively. Many of our predicted polycrystalline 2D materials have been observed by experiments, which strongly validates our theoretical predictions. This study greatly deepens our understanding of the 2D materials growth and the libraries are helpful for the future experimental synthesis of 2D polycrystals by choosing proper substrates.

Results and discussion

2D polycrystals of family-III/II or -III/VI

On a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate, threefold symmetric 2D materials show two equivalent low-energy orientations with opposite orientations (Fig. 1a, b)12,17,22,23,24,25. In addition, the threefold symmetric lattices of these 2D materials lead to anisotropic growth rates of their edges along various directions, and these 2D material grains usually have triangular shapes enclosed by three equivalent slowest-growing edges. We first carried out phase-field theory (PFT) simulations to investigate the kinetic coalescence behavior of two opposite triangular grains (Fig. 2a, b), See Supplementary Methods for simulation details and Supplementary Videos 1, 2 for the kinetic coalescence process. It is found that if the second grain is nucleated near one of the three edges of the first one, two vertices of the second grain disappear and a flat grain boundary (GB) is formed between the two parallel edges of the two triangular grains when they contact with each other (Second panel in Fig. 2a). Further growth leads to the formation of two GBs with a 60° angle to each other due to the propagation of the intersecting edges of the two grains (Third and fourth panels in Fig. 2a). Given the equal growth rates of these two grains, the two GBs are twin GBs and bisect the concave corners42. The polycrystalline island finally grows into a steady-state kite-like shape with four convex vertices and two concave ones (Fifth panel in Fig. 2a, also see Movie S1 for the whole coalescence process.). It is noted that the formed GBs are dominated by the growth kinetics of 2D crystals and GB migration in the polycrystal to achieve the most stable GB structure requires a much longer time than that of our simulations. Experimentally, migration of formed GBs during the growth of a 2D material was rarely observed. If the second grain is nucleated near one of the three vertices of the first one (Fig. 2b), their coalescence will lead one of the three vertices of both of the grains to disappear and the final polycrystal shows a drum-like shape with four convex vertices and two concave ones bisected by GBs. By analyzing the growth trajectories of the convex vertices of the two grains, we can predict whether the vertices will disappear during coalescence (See Supplementary Methods for detailed analysis). Figure 2c shows the predicted topography diagram for the coalescence of two opposite triangular grains. The first grain is represented by the blue triangle. If the second one (red triangle) is nucleated in area 1 (light gray), a polycrystal with shape 1 will be finally formed after coalescence. If the second one is nucleated in area 2 (dark gray), a polycrystal with shape 2 will be formed.

a, b PFT simulations showing two coalescence processes between two triangular grains with a 60o misorientation angle, respectively. Red dots represent the nucleation centers of the two triangular islands. The GBs in polycrystals are denoted by red lines. The fourth and fifth panels in (a, b) are properly zoomed out for a better view. c Topography diagram for the coalescence of two triangular grains with a misorientation angle of 60o. In the left panel, the blue triangle represents the first grain, areas colored in a light gray and dark gray show where the second island nucleates. Shapes 1 and 2 in the right panel show the shapes of the polycrystal formed by the coalescence of the first island and the second one that is nucleated in the light gray area and in the dark gray area, respectively.

In practice, many grains will be nucleated on a substrate during the growth of 2D materials. Coalescence between multiple grains leads to the formation of polycrystals with complex shapes. Here, we propose a general method of predicting all the possible steady-state shapes of 2D polycrystals.

For a steady-state polycrystal formed from the coalescence of misaligned 2D grains, its maximum number of convex vertices Nmax should be Nmax = NO × NSV, where NO is the number of different orientations of grains and NSV is the number of vertices of one grain. If the growth rates of all grains on a substrate are equal, which is a reasonable assumption because of the uniform chemical environment in a small substrate area (usually at μm scale) in a large CVD system, the distances from all the convex vertices of a polycrystal to its center are equal after the growth reaches to steady state. Therefore, the steady-state shape of a polycrystal with a maximum number of convex vertices can be constructed by superimposing single crystals of the same size but different orientations. For threefold symmetric 2D materials grown on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate, Nmax = NO × NSV = 2 × 3 = 6 and the steady-state shape is obtained by superposing two opposite triangular grains, as shown in Fig. 3a. In the superimposed structure, there are six convex vertices and six concave vertices. Since the concave vertices are bisected by GBs between neighboring grains42, the superposed area is divided into six sectors, which belong to the six convex corners, respectively (Fig. 3b).

a, b Schematics showing how to construct a polycrystal with the maximum number of convex vertices. c Schematics showing the method of constructing polycrystals with five convex vertices from the most complex polycrystalline 2D island. d A predicted library of 2D polycrystals of family-III/II or -III/VI. The lower panel shows the experimental observation of polycrystalline hBN islands grown on a Cu(110) surface. Reproduced from ref. 25 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. e, f PFT simulation on the growth process of a polycrystalline island with six and five convex vertices, respectively. The fifth panels in e, f are zoomed out for a better view.

Based on the obtained most complex polycrystal, all other possible steady-state polycrystals can be deduced. The number of convex vertices, NV, of a polycrystal of a threefold symmetric 2D material on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate should be larger than that of a single crystal and no more than that of the most complex polycrystal, thus NV ranges from NSV + 1 = 4 to Nmax = 6. Here, we define n = Nmax − NV as the number of convex vertices missing in a polycrystal as compared to the most complex one. Therefore, n can change from 0 to 2, with n = 0 corresponding to the most complex one. If n = 1, there is only one choice for the missing convex vertex from the six equivalent ones. The corresponding structure can be constructed by firstly deleting one sector from the most complex island, and then intersecting the two edges of the two neighboring convex vertices of the deleted one (Fig. 3c). If n = 2, there are only two non-equivalent choices from the six equivalent convex vertices, considering that GBs in a steady-state polycrystal correspond to concave vertices and thus the two missing convex vertices should not be neighbors to each other (Third panel in Fig. 3d)10,42. Summarizing the cases for n = 0, 1, and 2, there are totally four different types of polycrystals for threefold symmetric 2D materials that can be grown on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate, which are verified by Tay’s experiments on CVD growth of hBN on Cu(110) surfaces25 (Fig. 3d), as well as many other experimental observations, including hBN on Cu(111) surface23, hBN on Ge(110) surface26, WSe2 on Al2O3(0001) surface28, MoS2 on Al2O3(0001) surface29,30, and MoS2 on GaN(0001) surface31 (Supplementary Fig. 3 in Supplementary Information). The existence of GBs in hBN islands with the same shapes as our predicted ones has been verified by etching experiments17,43.

Finally, PFT simulations were performed to demonstrate the formation of polycrystals with six and five convex vertices shown in Fig. 3d. As shown in Fig. 3e, the polycrystal with six convex vertices can be formed by coalescence between one large triangular grain and three small opposite ones nucleated near each edge of the large grain (See Supplementary Video 3 for the coalescence process). Similarly, coalescence between a large single-crystalline island and two small ones with opposite orientations can lead to the formation of a polycrystalline island with five convex vertices, as demonstrated in Fig. 3f (See Supplementary Video 4 for the coalescence process).

2D polycrystals of family-III/IV

For threefold symmetric 2D materials grown on a fourfold symmetric substrate, triangular grains have four equivalent low-energy orientations, which have 30o, 60o, and 90o anti-clockwise misorientation angles between each other (Fig. 1c). Polycrystals formed from these misaligned grains are much more complex than those grown on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate.

Figure 4 shows the coalescence behaviors between two misaligned triangular grains. Except for the case with a misorientation angle of 60o (Fig. 4a, which is the same as that shown in the previous section.), we also obtained the topography diagrams for the coalescence between two triangular grains with 30o and 90o misorientation angles, which are mirror to each other (Fig. 4b, c, respectively. See Supplementary Methods for detailed analysis). Phase-field theory simulations were performed to demonstrate the coalescence processes between two triangular islands with a 30o misorientation angle (Fig. 4d, e also Supplementary Videos 5, 6), which are consistent with the predicted topography diagram.

a–c Topography diagrams for the coalescence of two triangular grains with an anti-clockwise misorientation angle of 60o, 30o, and 90o, respectively. The blue triangular grain is chosen as the reference. Light gray and dark gray areas denote where the second triangular grain is nucleated with respect to the first one, respectively. Shapes 1–2, 3–4, and 5–6 show the steady-state polycrystals formed from the coalescence between two grains with different misorientation angles. d, e PFT simulations showing the coalescence processes of two triangular grains with a 30o misorientation angle to form a polycrystal with shape 3 and shape 4, respectively. The fourth and fifth panels in (d, e) are zoomed out for a better view.

To obtain all possible steady-state polycrystals formed from the coalescence of an arbitrary number of triangular grains with four different orientations, the construction strategy proposed in the previous section is adopted. In the current case, Nmax = NO × NSV = 4 × 3 = 12, and the shape of the corresponding polycrystalline island can be obtained by superimposing four triangular islands with different orientations (Fig. 5a). NV of any polycrystals can thus range from 12 to 4. For NV = 11, the polycrystal is constructed by deleting any one of the 12 equivalent convex vertices and then filling the vacancy by connecting its two neighboring sectors, as shown in Fig. 5b. Figure 5c demonstrates another example of constructing a polycrystal with four evenly distributed convex vertices. Figure 5d shows a PFT simulation demonstrating the formation process of the polycrystal in Fig. 5c from the coalescence of four grains with different orientations (See Supplementary Video 7 for the coalescence process.). During coalescence, four perpendicular GBs are formed to separate the four grains. In addition, only one convex vertex in each grain is maintained in the steady-state polycrystal.

a Schematics on the construction of the steady-state polycrystal with the largest number (12) of convex vertices formed from the coalescence of triangular grains with four different orientations on an fcc(100) surface. b, c Schematics on the construction of the steady-state polycrystals with 11 and 4 convex vertices based on the polycrystal with 12 convex vertices, respectively. Convex vertices that are chosen to disappear are denoted by dashed outlines. d PFT simulation showing an example of the formation of a polycrystal by coalescence of four single-crystalline islands with different orientations. The fifth panel is zoomed out for a better view.

Following the above construction method, 9, 31, 59, 59, 42, 19, and 6 different steady-state polycrystals can be obtained for NV ranging from 4 to 10, respectively (See Supplementary Methods for detailed analysis.). Figure 6a shows the library of 2D polycrystals of family-III/IV. Some of our predicted polycrystals have been observed in the CVD growth of hBN on Cu(100) surfaces. As shown in the left panel of Fig. 6b, three types of polycrystalline hBN islands with NV = 4 and one type with NV = 5 have been found in Song’s experiments44. In addition, four types of polycrystalline hBN islands with NV = 4 and two types with NV = 5 were also observed in Wang’s experiments (middle and right panels in Fig. 6b)17.

a The library of polycrystals in family-III/IV. The polycrystals are classified by their number of convex vertices. b SEM images of CVD grown hBN on Cu(100) surfaces. Polycrystalline hBN grains of different types are highlighted by dashed circles with different colors. The corresponding theoretical models are added near these polycrystalline hBN islands. Left panel, copyright from ref. 44. Middle and right panels, reprinted with permission from ref. 17, Copyright 2019 Springer Nature.

2D polycrystals of family-IV/III or -IV/VI

For fourfold symmetric 2D materials grown on a three- or six-fold symmetric substrate, 2D grains have three equivalent low-energy orientations with 30o × m (m = 0, 1, 2) misorientation angles (Fig. 1d, e). Here, we start with the coalescence of two square grains with different orientations and then explore all the possible polycrystals that are formed from the coalescence of an arbitrary number of square grains.

Figure 7a, b show two PFT simulations demonstrating the coalescence processes of two square grains with a 30o misorientation angle, respectively. (See Supplementary Methods for the simulation details, Supplementary Videos 8, 9 for the coalescence processes). As shown in Fig. 7a, if the second grain is nucleated near the edges of the first one, three of the four convex vertices of the second grain disappear and only one vertex is left after coalescence, leading to a polycrystal with five convex and two concave vertices, respectively. When the second grain is nucleated near one of the vertices of the first one, two vertices of the second grain and one vertex of the first grain will disappear during the coalescence (Fig. 7b). By a geometry analysis similar to that of threefold symmetric 2D materials, it is found that the above two types of polycrystals are the only polycrystals that can be formed from the coalescence of two square islands with a 30o misorientation angle, and the corresponding topography diagram is shown in Fig. 7c (See Supplementary Methods for the analysis details). In addition, it is seen that the probability of forming a polycrystal with shape 1 is much lower than that of forming a polycrystal with shape 2 because area 1 (light gray) for the nucleation of the second grain to coalesce with the first grain to form a polycrystal with shape 1 is limited by the size of the first grain, while area 2 (dark gray) is infinitely large. If the second gain shows a 60o anti-clockwise misorientation angle with respect to the first one, the formed polycrystals are mirrors to those with a 30o misorientation angle, as demonstrated by PFT simulations shown in Fig. 7d, e, Movies S10, S11, and the corresponding topography diagram shown in Fig. 7f.

a, b PFT simulations showing two coalescence processes of two square grains with an anti-clockwise misorientation angle of 30o, respectively. The fifth panels are zoomed out for a better view. c Topography diagram for the coalescence of two square 2D grains with an anti-clockwise misorientation angle of 30o. In the left panel, the first grain is represented by the blue square. The second grain (small red square) is nucleated in either light gray area 1 or dark gray area 1. Shape 1 or 2 in the right panel will be finally formed after coalescence between these two grains, with the second grain nucleated in area 1 or area 2, respectively. d, e PFT simulations showing two coalescence processes of two square grains with an anti-clockwise misorientation angle of 60o, respectively. The fifth panels are zoomed out for a better view. f Topography diagram for the coalescence of two square 2D grains with an anti-clockwise misorientation angle of 60o.

Similar to polycrystals of family-III/IV, the Nmax of a steady-state polycrystal of family-IV/III or -IV/VI is also 12 (Fig. 8a). However, the inner angle of the concave corner of this polycrystal is 120o rather than 90o, as compared to the polycrystal with 12 convex vertices of family-III/VI. Figure 8b shows an example of constructing a polycrystal with eight convex vertices based on the most complex polycrystal. Four evenly distributed convex vertices (outlined by red dashed lines in the second panel in Fig. 8b) from the 12 equivalent vertices of the most complex polycrystal are chosen to disappear (third panel in Fig. 8b). The growth of such a polycrystal can be realized by nucleating one 30o-misoriented square grain near each edge of large square grain, as demonstrated by the PFT simulation shown in Fig. 8c (also Supplementary Video 12). Figure 8d shows another example of the construction of a polycrystal with six convex vertices, where three pairs of convex vertices from the twelve vertices of the most complex polycrystal are chosen to disappear. PFT simulations show that this polycrystal can be formed by three grains that show different orientations (Fig. 8e and Supplementary Video 13).

a Schematics on the construction of the steady-state polycrystal with the largest number (12) of convex vertices formed from the coalescence of square grains with three different orientations. The relative orientation angle of each grain is provided. b, d Schematics on the construction of the steady-state polycrystalline island with eight and six convex vertices based on the polycrystalline island with 12 convex vertices, respectively. Convex vertices that are chosen to disappear are denoted by dashed outlines in the second panel. c, e PFT simulation showing an example of the formation of a polycrystalline island in (b, d), respectively. The fourth and fifth panels in (c) and the fifth panel in (e) are zoomed out for a better view.

To construct all the steady-state polycrystals, 7 to 0 convex vertices of the 12 equivalent vertices of the most complex polycrystal need to be deleted, leading to 6, 26, 38, 35, 18, 6, 1, and 1 different kind of steady-state polycrystal shapes for NV increasing from 5 to 12, respectively (Fig. 9, also see Supplementary Methods for details). Experimentally, the fourfold symmetric square FeSe grains have been synthesized on a graphene surface by MBE45, while polycrystalline FeSe islands were not reported yet. More studies are needed to verify our theoretical prediction.

Polycrystals of family-VI/IV

Our previous study on graphene synthesis on liquid Cu surface showed that, during the coalescence of the randomly oriented graphene islands, these islands tend to be parallelly aligned with each other or have a 30o misorientation angle between neighboring ones to reduce the GB formation energy11. In that study, we have predicted a family of 30 types of graphene polycrystals and 27 of them were observed experimentally. On a fourfold symmetric surface, the misorientation angle between two misaligned 2D materials with sixfold symmetry is also 30o. Therefore, a sixfold symmetric 2D material on a fourfold symmetric substrate can also form 30 types of 2D polycrystals, as shown in Fig. 4 in ref. 11.

It is worth mentioning that we used the inner angle of each single-crystalline sector in a polycrystalline graphene island to construct the shape of the polycrystalline island in ref. 11, because the sector inner angle can fully define the single-crystalline sector in that case. However, for three- or four-fold symmetric 2D materials discussed above, there is no one-to-one correspondence between the sector inner angle and the sector shape. For instance, there are two types of sectors that have the same sector inner angle but different shapes in the polycrystal shown in Fig. 8b. Therefore, using the sector inner angle to describe the polycrystal is incomplete in such situations. The proposed strategy for constructing steady-state 2D polycrystals in this study can effectively solve this problem. In addition, this study is focused on the formation mechanism of 2D polycrystals formed from the in-plane coalescence of monolayer 2D crystals, which is the most popular case of 2D materials synthesis.

In summary, the formation mechanism of polycrystals of various 2D materials on different substrates has been thoroughly explored. The kinetics of 2D polycrystal growth leads to a general strategy of constructing 2D polycrystals and four libraries of 2D polycrystals are built, including a family of 4 types of polycrystals of threefold symmetric 2D materials on a two- or six-fold symmetric substrate (family-III/II or –III/VI); a family of 227 types of polycrystals of threefold symmetric 2D materials on a fourfold symmetric substrate (family-III/IV); a family of 131 types of polycrystals of fourfold symmetric 2D materials on a three- or six-fold symmetric substrate (family-IV/III or –IV/VI); a family of 30 types of polycrystals of sixfold symmetric 2D materials on a fourfold symmetric substrate (family-VI/IV). Our theoretical prediction of the formation of polycrystalline 2D materials was consistent with many experimental observations. For instance, all the predicted polycrystals of family-III/II or –III/VI were observed in the chemical vapor deposition of hBN on (110) and (111) surfaces of Cu, and seven out of the family-III/IV have also been observed in hBN growth on Cu(100) surfaces. This study provides an in-depth understanding of the formation of polycrystalline 2D materials, which could help experiments for controllable synthesis of 2D materials via choosing proper substrates.

Methods

Phase-field theory simulations were carried out to simulate the coalescence process of misaligned grains with different symmetries. A detailed description of the phase-field model and the parameters used in the phase-field theory simulations are given in the Supplementary Information. In the PFT simulations, we have neglected the effect of precursor diffusion. Both previous PFT simulations and other studies have shown that faceted 2D crystals are grown under an attachment-limited regime, which is dominated by the attachment kinetics of atoms to the edges of 2D crystals rather than the diffusion of precursor35,46. If diffusion is the dominant factor, 2D crystals will grow into fractal shapes35,46, making the formation of polycrystals much more complicated, which needs further study in the future. In addition, we have assumed that the substrate is flat. Yu et al. have shown that an artificially made non-planar substrate with a large curvature can lead to the self-coalescence of a 2D crystal and thus the formation of a GB41, while such an effect is not observed in most CVD experiments. The topography diagrams for the coalescence of two misaligned grains with different symmetries are obtained by a geometry analysis, which is based on the assumption that the growth rates of the two grains are the same. A detailed description of the geometry analysis is also given in the Supplementary Information. Derivation of the number of different polycrystals of 2D materials with different symmetries on substrates with various substrates is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Code availability

The code for PFT simulations of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Bonaccorso, F., Sun, Z., Hasan, T. & Ferrari, A. C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photonics 4, 611–622 (2010).

Sun, Z. & Chang, H. Graphene and graphene-like two-dimensional materials in photodetection: mechanisms and methodology. ACS Nano 8, 4133–4156 (2014).

Xia, F., Wang, H., Xiao, D., Dubey, M. & Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899–907 (2014).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Ma, W. et al. Interlayer epitaxy of wafer-scale high-quality uniform AB-stacked bilayer graphene films on liquid Pt3Si/solid Pt. Nat. Commun. 10, 2809 (2019).

Huang, M. et al. Large-area single-crystal AB-bilayer and ABA-trilayer graphene grown on a Cu/Ni(111) foil. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 289–295 (2020).

Ma, T. et al. Edge-controlled growth and kinetics of single-crystal graphene domains by chemical vapor deposition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20386–20391 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Edge-controlled growth and etching of two-dimensional GaSe monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 482–491 (2017).

Wang, Z.-J. et al. The coalescence behavior of two-dimensional materials revealed by multiscale in situ imaging during chemical vapor deposition growth. ACS Nano 14, 1902–1918 (2020).

Dong, J., Geng, D., Liu, F. & Ding, F. Formation of twinned graphene polycrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 7723–7727 (2019).

Dong, J., Zhang, L., Dai, X. & Ding, F. The epitaxy of 2D materials growth. Nat. Commun. 11, 5862 (2020).

Lee, J.-H. et al. Wafer-scale growth of single-crystal monolayer graphene on reusable hydrogen-terminated germanium. Science 344, 286–289 (2014).

Xu, X. et al. Ultrafast epitaxial growth of metre-sized single-crystal graphene on industrial Cu foil. Sci. Bull. 62, 1074–1080 (2017).

Deng, B. et al. Wrinkle-free single-crystal graphene wafer grown on strain-engineered substrates. ACS Nano 11, 12337–12345 (2017).

Nguyen, V. L. et al. Seamless stitching of graphene domains on polished copper (111) foil. Adv. Mater. 27, 1376–1382 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Epitaxial growth of a 100-square-centimetre single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayer on copper. Nature 570, 91–95 (2019).

Chen, T.-A. et al. Wafer-scale single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayers on Cu (111). Nature 579, 219–223 (2020).

Yang, P. et al. Epitaxial growth of centimeter-scale single-crystal MoS2 monolayer on Au (111). ACS Nano 14, 5036–5045 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Epitaxial growth of wafer-scale molybdenum disulfide semiconductor single crystals on sapphire. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1201–1207 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Dual-coupling-guided epitaxial growth of wafer-scale single-crystal WS2 monolayer on vicinal a-plane sapphire. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 33–38 (2021).

Song, X. et al. Chemical vapor deposition growth of large-scale hexagonal boron nitride with controllable orientation. Nano Res. 8, 3164–3176 (2015).

Uchida, Y., Iwaizako, T., Mizuno, S., Tsuji, M. & Ago, H. Epitaxial chemical vapour deposition growth of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride on a Cu(111)/sapphire substrate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 8230–8235 (2017).

Wood, G. E. et al. van der Waals epitaxy of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride on copper foil: growth, crystallography and electronic band structure. 2D Mater. 2, 025003 (2015).

Tay, R. Y. et al. Synthesis of aligned symmetrical multifaceted monolayer hexagonal boron nitride single crystals on resolidified copper. Nanoscale 8, 2434–2444 (2016).

Yin, J. et al. Aligned growth of hexagonal boron nitride monolayer on germanium. Small 11, 5375–5380 (2015).

Liu, L. et al. Unusual role of epilayer–substrate interactions in determining orientational relations in van der Waals epitaxy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16670–16675 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Diffusion-controlled epitaxy of large area coalesced WSe2 monolayers on sapphire. Nano Lett. 18, 1049–1056 (2018).

Aljarb, A. et al. Substrate lattice-guided seed formation controls the orientation of 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 9215–9222 (2017).

Dumcenco, D. et al. Large-area epitaxial monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano 9, 4611–4620 (2015).

Ruzmetov, D. et al. Vertical 2D/3D semiconductor heterostructures based on epitaxial molybdenum disulfide and gallium nitride. ACS Nano 10, 3580–3588 (2016).

Murdock, A. T. et al. Controlling the orientation, edge geometry, and thickness of chemical vapor deposition graphene. ACS Nano 7, 1351–1359 (2013).

Artyukhov, V. I., Hu, Z., Zhang, Z. & Yakobson, B. I. Topochemistry of Bowtie- and star-shaped metal dichalcogenide nanoisland formation. Nano Lett. 16, 3696–3702 (2016).

Momeni, K. et al. Multiscale computational understanding and growth of 2D materials: a review. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 22 (2020).

Meca, E., Shenoy, V. B. & Lowengrub, J. Phase-field modeling of two-dimensional crystal growth with anisotropic diffusion. Phys. Rev. E 88, 052409 (2013).

Ye, H. et al. Toward a mechanistic understanding of vertical growth of van der Waals stacked 2D materials: a multiscale model and experiments. ACS Nano 11, 12780–12788 (2017).

Guo, Z., Price, C., Shenoy, V. B. & Lowengrub, J. Modeling the vertical growth of van der Waals stacked 2D materials using the diffuse domain method. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 28, 025002 (2020).

Momeni, K., Ji, Y., Zhang, K., Robinson, J. A. & Chen, L.-Q. Multiscale framework for simulation-guided growth of 2D materials. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 27 (2018).

Ji, Y., Momeni, K. & Chen, L.-Q. A multiscale insight into the growth of h-BN: effect of the enclosure. 2D Mater. 8, 035033 (2021).

Momeni, K., Ji, Y. & Chen, L.-Q. Computational synthesis of 2D materials grown by chemical vapor deposition. J. Mater. Res. 37, 114–123 (2022).

Yu, H. et al. Tilt grain boundary topology induced by substrate topography. ACS Nano 11, 8612–8618 (2017).

Guo, W. et al. Governing rule for dynamic formation of grain boundaries in grown graphene. ACS Nano 9, 5792–5798 (2015).

Yin, J. et al. Large single-crystal hexagonal boron nitride monolayer domains with controlled morphology and straight merging boundaries. Small 11, 4497–4502 (2015).

Song, X. et al. Wafer-scale CVD growth of monolayer hexagonal boron nitride with large domain size by Cu foil enclosure approach. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1501.01740v1 (2015).

Song, C.-L. et al. Molecular-beam epitaxy and robust superconductivity of stoichiometric FeSe crystalline films on bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 84, 020503 (2011).

Zhuang, J. et al. Morphology evolution of graphene during chemical vapor deposition growth: a phase-field theory simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 9902–9908 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R019-D1), South Korea, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB30000000), P. R. China. Computational resources from Cimulator at CMCM of IBS and TianHe-1(A) at the National Supercomputer Center at Tianjin are also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.D. and Y.L. supervised the research. J.D. performed calculations and data analysis. J.D., F.D., and Y.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, J., Liu, Y. & Ding, F. Mechanisms of the epitaxial growth of two-dimensional polycrystals. npj Comput Mater 8, 109 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00797-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00797-5