Abstract

Nature frequently employs the buckling phenomenon to facilitate the formation of complicated patterns across length-scales. Current knowledge, however, is limited to a small set of buckling-induced microstructure transformations in soft composites; and the pattern formation phenomenon remains largely unknown for a vast pool of material morphologies. Here, we investigate the unexplored rich domain of soft heterogeneous composites. We experimentally observe the formation of instability-driven domains in stratified composites with a non-dilute stiff phase. We illustrate that the discovered domain patterns are energetically favorable over wrinkling. Moreover, we introduce a closed-form analytical expression allowing us to predict the evolution of the patterns in the post-buckling regime. Finally, we show that various patterns can be pre-designed via altering material compositions. These findings can help advance our understanding of the mechanisms governing pattern formations in soft biological tissues, and potentially enable the platform for mechanical metamaterials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological systems frequently employ the buckling phenomenon as a part of complex processes to form a variety of patterns from the folds of brain cortex1 and the rippled edges of leaves and flower petals2 to the helical coils of plant roots3. Understanding of the mechanisms that give rise to the phenomenon is essential for unraveling the evolution of biological systems4,5. Moreover, the associated elastic instabilities or buckling phenomena can be used to design new materials and systems with unusual properties and functions6,7. These ideas, combined with the recent advances in material manufacturing8 have resulted in the design of mechanical metamaterials9,10, switchable optical11 and acoustic12 filters, reversible auxetic materials13. Furthermore, these material systems hold significant potential for diverse applications in soft robotics14, sensors15, flexible electronics16, adhesive systems17,18, and unique product identifiers19.

Elastic instabilities in soft microstructured materials can develop at various length scales that are dictated by the constituent material properties and microstructural geometries20. These critical length-scales can be detected by (superimposed “small-on-large”21) Bloch wave instability analysis22. The long-wave limit of the analysis is equivalent to the loss of ellipticity condition23 that can be effectively expressed in terms of homogenized material moduli. In fact, in many soft composites, these so-called long wave or macroscopic instabilities are theoretically predicted to develop before microscopic instabilities of the length-scales comparable with microstructure characteristic sizes. Thus, for example, the finite length-scale instabilities happen only at the very limited range of dilute volume fractions of stiffer fibers24,25; whereas, in the extensive range of material morphologies, the long-wave instabilities are to develop.

Here, we investigate this unexplored rich domain of soft material morphologies that give rise to long-wave instabilities. As we shall show, this type of instability gives rise to formations of fully determined and highly ordered microstructures in the post-buckling regime. We illustrate the concept with the example of periodic non-dilute layered composites for which the long-wave instability is predicted. We experimentally observe the formation of twinning patterns and their transition to the classical microscopic wavy patterns in 3D-printed soft composites. Through numerical modeling, we show that the development of the twinning pattern is energetically favorable over the wavy pattern in these soft composites. In addition, a closed-form analytical expression is introduced to predict the evolution of the domains in the post-buckling regime. Finally, we investigate the influence of geometrical microstructure parameters and material properties on pattern formations.

Results and discussion

Observation of instability-induced domain pattern

We start with considering the soft layered composite with a non-dilute stiff phase volume fraction (illustrated in Fig. 1a), where the composite is predicted to develop long-wave instability, upon exceeding the critical value of the compressive strain along the layers. Our experimental observations, however, reveal the formation of a twinning microstructure characterized by finite-size anti-symmetric domains. Figure 1b illustrates the experimentally observed twinning pattern in the composite with the stiff layer volume fraction of c(l) = 0.5. The realized domain pattern is distinctly different from the classical wrinkling26. We note that geometrically similar domain or twinning patterns were also identified in various systems, such as particle reinforced composites27, thin films on compliant substrates28,29, liquid crystals30, and nematic elastomers31,32.

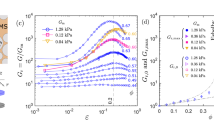

a Schematic illustration of periodic layered composites. b Instability-induced twinning microstructure in layered composite with \(c^{(l)} = 0.50\) at strain level ε = 0.16. Scale bar: 10 mm. c Evolution of domain orientation angle as a function of applied strain. Error bars refer to standard deviations of the experimentally calculated orientation angles based on selected domains.

The evolution of the observed domain orientation is shown in Fig. 1c. Initially, the layers maintain their flat shape, however, upon exceeding the critical strain, the domains start forming, and the orientation angle rapidly increases. This is also captured by our numerical modeling predicting the onset of instabilities and post-buckling behavior. To provide an estimate for the evolution of the domain pattern, we assume that (i) the domains are wide enough in comparison to the width of the localized domain interphase region, (ii) the deformation in stiffer and softer layers is piece-wise homogeneous. The buckling strain is obtained based on the loss of ellipticity analysis [20]. Under those assumptions and energy considerations, we derived closed-form expressions to predict the deformation field of domain pattern in the layered composite for both 2D and 3D layer composite. The equation derivation details are provided in Supplementary Note 4. Thus, the domain orientation angle for 2D layered composite under the plane-strain conditions can be expressed as

where λ denotes the stretch ratio related to the strain as λ = 1 − ε; ε is the applied compressive strain along layer direction. The effective elastic moduli are \(\bar \mu = c^{(l)}\mu ^{(l)} + c^{(m)}\mu ^{(m)}\), and \(\tilde \mu = \mu ^{(l)}\mu ^{(m)}/\left( {c^{(l)}\mu ^{(m)} + c^{(m)}\mu ^{(l)}} \right),\) where μ and c denote the shear modulus and phase volume fraction, respectively; the superscripts (l) or (m), corresponding to the stiffer layer or soft matrix, respectively. We note the agreement between the numerical results and the analytical expressions, as well as the agreement with the experimental observations shown in Fig. 1c.

Transition from domain pattern to classical wrinkle

The presented results thus far are for the composite with a relatively large stiff layer volume fraction, illustrating the formation of the twinning patterns, whereas the classical wavy mode develops in the composites with dilute stiff layer volume fraction. To illustrate the transition from domains to wrinkling modes, we show the critical wavenumber and critical strain as functions of the stiff phase volume fraction in Fig. 2. We observe that the non-dilute laminates develop domain patterns (see Fig. 2a, b), whereas the composites with small stiff layer volume fractions transition to the wrinkle patterns (see Fig. 2d). Thus, a decrease in stiffer phase volume fraction leads to the transition in instability-triggered pattern from domain to wrinkling microstructure, owing to a significant decrease in the interaction between stiffer layers.

a \(c^{(l)} = 0.50\), b \(c^{(l)} = 0.30\), c \(c^{(l)} = 0.15\), d \(c^{(l)} = 0.01\). The deformed configurations are given at ε = 0.16 (a), 0.19 (b), and 0.22 (c, d). Scale bar: 10 mm. e Numerical prediction of critical strain and critical wavenumber vs. stiffer layer volume fraction in soft laminates. The dashed vertical line denotes the transition value of the volume fraction between long-wave and microscopic instability. Blue circular and black triangular points refer to the experimental critical strains and wavenumbers, respectively. The dotted and continuous curves are numerical results for microscopic and long-wave instabilities, respectively. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

To elucidate the mechanism of the transition of buckling mode, Fig. 2e shows the critical wavenumber and critical strain as functions of the stiff phase volume fraction. The continuous curves are detected numerically through the Bloch-Floquet instability analysis, while discrete points are the experimental results. The initial constituent shear modulus contrast is \(\mu ^{(l)}/\mu ^{(m)} = 49\). The numerical instability analysis predicts the transition from the microscopic instability (dotted curves) to long-wave one at the volume fraction c(l) ≈ 0.092. We observe a qualitative agreement between experimental and numerical results. Both experiments and simulations show that the critical strain and critical wavenumber decrease with an increase in stiffer layer volume fraction. For the composite approaching dilute volume fractions, both critical strain and critical wavenumber barely change with volume fraction (\(c^{(l)} \lesssim 0.04\)). This is due to weakening interactions between stiffer layers, as the distance between them increases. Moreover, the analysis does predict the corresponding change in the instability mode. We note, however, that the experiments show the development of the finite length-scale microstructures as opposite to the dramatic increase in the critical wavelength that would correspond to the long-wave mode for the composites with non-dilute volume fraction beyond the threshold.

Mechanism of domain pattern formation

To study the mechanism for the formation of finite length-scale domains in the non-dilute composite, we perform the numerical post-buckling analysis. In the post-buckling analysis, we enforce the development of instability modes with different wavelengths by imposing small-amplitude geometrical imperfections and microstructural periodicity. Figure 3a presents the stress map of the composite with experimentally observed twinning microstructure (c(l) = 0.5). The stress is normalized by the effective modulus \(\bar \mu\). We observe that in the postbuckling regime, the stress state initially significantly decreases with an increase in buckled wavelength, however, when the buckled wavelength exceeds a threshold value (Lcr/t ≈ 40), the stress surface exhibits a plateau feature. Moreover, we note that the critical strain function does not exhibit a minimum for any wavelength in the considered range, and the function asymptotically approaches the value \(\varepsilon _{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}} = 1 - \left( {1 - \tilde \mu /\bar \mu } \right)^{\frac{1}{4}}\) corresponding to the onset of long-wave instabilities20. Note that our post-buckling analyses indicate that the buckling wavelength of the domain pattern is sensitive to initial imperfections; the sensitivity is illustrated by our numerical analysis in Supplementary Note 5. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the corresponding experimentally observed critical wavelength Lcr/t = 37.5 and critical strain εcr = 0.025, are found to be close to the plateau values. These observations are consistent with the results given in Fig. 2e, showing that the composite with no minimum strain function buckles at the wavelength that is significantly smaller than the overall sample size. We note that a similar phenomenon was also observed in the herringbone mode arisen in the buckling of thin films on compliant substrates29,33.

Next, we numerically illustrate the hypothesis that the twinning patterns are energetically favorable than the wavy modes in the composites with a non-dilute stiff phase. Figure 3b shows the evolution of the elastic energy in the laminates with twinning and wavy modes. Note that the numerical simulations fully account for the highly localized deformation at the domain interfaces. The energy is normalized by the stored energy value in the corresponding flat laminate \(W_0 = \frac{{\bar \mu }}{2}(\lambda ^2 + \lambda ^{ - 2} - 2)\). The energy functions are calculated from the post-buckling analysis, and the examples are given for the experimentally observed wavelength. We observe that upon the onset of instability, the normalized energy functions for the twinning (solid black) and wavy (dashed blue curve) patterns rapidly decrease. Importantly, the domain pattern results in a lower energy state, and the difference in the stored energies increases with an increase in deformation. Thus, the example illustrates that the domain microstructures are energetically favorable over the wavy pattern in the composite with the non-dilute stiff phase volume fraction, for which the long-wave instability is theoretically predicted.

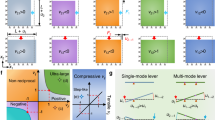

Pattern evolution process and morphology map

We finally study the influence of the composite morphology, its microstructural geometry, and constituent material properties, on the evolution of these distinct patterns. To this end, we introduce a measure for quantifying the post-buckling mode shape. We define a weighted function for fitting the post-buckling microstructural geometry as a combination of the domain and wavy-like geometrical shapes. The function is given as \(X_1 = A\left( {pf_t\left( {X_2/(\lambda L_{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}})} \right) + (1 - p)\sin \left( {2\pi X_2/(\lambda L_{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}})} \right)} \right)\), where A denotes the pattern amplitude, and ft (ξ) is the domain shape function defined in Supplementary Note 6; p is the shape weight coefficient, defined such that, when p is close to 1, the stiffer layer develops in domain microstructure; whereas, the wrinkling mode dominates when p is close to 0. Figure 4a shows the shape coefficient values plotted versus applied strain for laminates with various stiffer phase volume fractions. The shape weight coefficient for the case c(l) = 0.16 rapidly increases from 0 to nearly 1 upon exceeding the critical strain, thus, indicating the formation of the twinning patterns in the post-buckling regime. However, the laminate with a slightly low stiff phase volume fraction, \(c^{(l)} = 0.14\), experiences microscopic instability with the wavelength \(L_{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}}/t = 14.01\), and the shape weight coefficient is nearly 0, showing that the buckled pattern develops in the wavy mode. Note that for the considered laminates (with initial shear modulus ratio \(\mu ^{(l)}/\mu ^{(m)} = 10\)), the classical analysis predicts the transition from the microscopic to long-wave instabilities at \(c^{(l)} = 0.155\). In the vicinity of this composition, the laminates (for example, with volume fractions \(c^{(l)} = 0.148\) (blue), 0.150 (orange), 0.152 (green)) exhibit transitional patterns manifesting in merged twinning and wavy modes.

a Evolution of shape coefficient as functions of applied deformation levels for layered composites with shear moduli contrast \(\mu ^{(l)}/\mu ^{(m)} = 10\). b The shape coefficient map for layered composites with various shear modulus contrasts and stiffer layer volume fractions. The value of the shape weight coefficient p is evaluated at the well-resolved post-buckling stage of strain-level ε = εcr + 0.2.

To complete the picture of the material composition influence on the post-buckling behavior, we show the shape weight coefficient map as functions of stiffer layer volume fraction and shear modulus contrast in Fig. 4b. The dashed black curve separates the compositions developing wavy (on the left side of the curve) and twinning (on the right side of the curve) microstructures. In addition, there is a narrow range of volume fraction (depending on the shear modulus contrast), at which the laminates exhibit transitioning buckling modes combining wavy and twinning patterns. This transition range narrows as the shear modulus contrast is increased.

In summary, we have revealed an instability-induced twinning microstructure in soft layered composites. We experimentally demonstrated the formation of twinning microstructures in 3D printed laminates with a large stiff layer volume fraction. We illustrated that the domain patterns are energetically favorable and are characterized by a lower energy state over the corresponding classical wavy modes. We have derived an analytical estimate allowing us to predict the evolution and energy states of the domain patterns in the post-buckling regime.

Moreover, we have analyzed the influence of the soft composite compositions on the instability-induced patterns, and provided the guidelines for designing tunable materials systems with tailored microstructure transformations through initial compositions. We note that the soft composites can recover their original shape and microstructure upon realizing the applied loadings. Thus, the revealed twinning microstructures can be used for achieving fully reversible switchable properties and functionalities associated with the dramatic microstructure transformations. Our findings can help advance further development of reconfigurable material system platforms for tunable optical34 and acoustic35 devices, soft robotics36, stretchable electronics37, and biomedical devices38. In addition, we have identified shared characteristic instability feature in soft composites for which long-wave instability mode is predicted. We expect the observation of domain patterns in other soft composite systems across length scales. Thus, our findings provide a method for creating new patterns at ordered low-scale material systems such as block copolymers39,40,41. The phenomenon merged with the self-assembly process can help enhance the functionalities of material systems with a wide variety of controllable morphologies.

Methods

Experimental details

To realize the instability-induced patterns in experiments, we fabricated layered composite samples with periodic stiffer layers embedded in a soft matrix (schematically illustrated in Fig. 1a) using a multi-material 3D printer Object Connex 260. The stiffer layers and soft matrix were printed in digital material FLX9795 and TangoBlackPlus, respectively. Samples with stiffer layer volume fraction c(l) = 0.01, 0.15, 0.3, and 0.5 were prepared. The thickness of stiffer layers was fixed as \(t^{(l)} = 0.8\) mm, and the layered composites with various stiffer layer volume fractions were obtained via altering soft layer thickness. The in-plane width and height of all samples were 110 × 90 mm, while the out-of-plane thickness was 5 mm. The sample was placed vertically between two transparent parallel acrylic sheets held on a machined aluminum base, to prevent the out-of-plane deformation similar to the plane-strain conditions. The fixture acrylic sheets and specimens were lubricated with mineral oil to diminish the friction effect. Each sample was compressed in the layer direction at a strain rate of 2 × 10−4 s−1 using a Shimadzu EZ-LX testing machine.

Numerical simulation details

Numerical simulations were performed using the finite element code COMSOL 5.2a. The model was constructed in 2D under the under plane-strain conditions. The mechanical behaviors of the stiffer layer material and soft matrix material were modeled as nearly incompressible neo-Hookean materials with \(\mu ^{(l)} = 10.29\) MPa, and \(\mu ^{(m)} = 0.21\) MPa, respectively (see Supplementary Note 1 for the detailed material model). To detect the instability-associated critical wavenumber kcr and critical strain εcr in periodic structures, the analysis was conducted by employing the BlochFloquet technique superimposed on the finitely deformed state22,23 (see Supplementary Note 2 for details). Moreover, postbuckling analyses were also conducted via constructing the updated unit cells with height \(L_{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}} = 2{\uppi}/k_{{{{\mathrm{cr}}}}}\), and imposing periodic displacement boundary conditions on the edges of the unit cell (see Supplementary Note 3 for details).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Tallinen, T. et al. On the growth and form of cortical convolutions. Nat. Phys. 12, 588–593 (2016).

Huang, C., Wang, Z., Quinn, D., Suresh, S. & Hsia, K. J. Differential growth and shape formation in plant organs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12359–12364 (2018).

Silverberg, J. L. et al. 3D imaging and mechanical modeling of helical buckling in Medicago truncatula plant roots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16794–16799 (2012).

Ciarletta, P., Balbi, V. & Kuhl, E. Pattern selection in growing tubular tissues. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 248101 (2014).

Cheewaruangroj, N., Leonavicius, K., Srinivas, S. & Biggins, J. S. Peristaltic elastic instability in an inflated cylindrical channel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 68003 (2019).

Kochmann, D. M. & Bertoldi, K. Exploiting microstructural instabilities in solids and structures: From metamaterials to structural transitions. Appl. Mech. Rev. 69, 050801 (2017).

Mullin, T., Deschanel, S., Bertoldi, K. & Boyce, M. C. Pattern transformation triggered by deformation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 084301 (2007).

Singamaneni, S. et al. Instabilities and pattern transformation in periodic, porous elastoplastic solid coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 1, 42–47 (2009).

Liu, J. et al. Harnessing buckling to design architected materials that exhibit effective negative swelling. Adv. Mater. 28, 6619–6624 (2016).

Overvelde, J. T. B., Dykstra, D. M. J., de Rooij, R., Weaver, J. & Bertoldi, K. Tensile instability in a thick elastic body. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 094301 (2016).

Krishnan, D. & Johnson, H. T. Optical properties of two-dimensional polymer photonic crystals after deformation-induced pattern transformations. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 57, 1500–1513 (2009).

Wang, P., Casadei, F., Shan, S., Weaver, J. C. & Bertoldi, K. Harnessing buckling to design tunable locally resonant acoustic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 014301 (2014).

Bertoldi, K., Reis, P. M., Willshaw, S. & Mullin, T. Negative Poisson’s ratio behavior induced by an elastic instability. Adv. Mater. 22, 361–366 (2010).

Chen, T., Bilal, O. R., Shea, K. & Daraio, C. Harnessing bistability for directional propulsion of soft, untethered robots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5698–5702 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Super-elastic graphene ripples for flexible strain sensors. ACS Nano 5, 3645–3650 (2011).

Fu, H. et al. Morphable 3D mesostructures and microelectronic devices by multistable buckling mechanics. Nat. Mater. 17, 268–276 (2018).

Chan, E. P., Smith, E. J., Hayward, R. C. & Crosby, A. J. Surface wrinkles for smart adhesion. Adv. Mater. 20, 711–716 (2008).

Lin, P. C., Vajpayee, S., Jagota, A., Hui, C. Y. & Yang, S. Mechanically tunable dry adhesive from wrinkled elastomers. Soft Matter 4, 1830 (2008).

Yin, J. & Boyce, M. C. Unique wrinkles as identity tags. Nature 520, 164–165 (2015).

Triantafyllidis, N. & Maker, B. N. On the comparison between microscopic and macroscopic instability mechanisms in a class of fiber-reinforced composites. J. Appl. Mech. 52, 794–800 (1985).

Ogden, R. W. Non-linear Elastic Deformations (Dover Publications, 1997).

Bertoldi, K. & Boyce, M. C. Wave propagation and instabilities in monolithic and periodically structured elastomeric materials undergoing large deformations. Phys. Rev. B 78, 184107 (2008).

Geymonat, G., Müller, S. & Triantafyllidis, N. Homogenization of nonlinearly elastic materials, microscopic bifurcation and macroscopic loss of rank-one convexity. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 122, 231–290 (1993).

Parnes, R. & Chiskis, A. Buckling of nano-fibre reinforced composites: A re-examination of elastic buckling. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 50, 855–879 (2002).

Slesarenko, V. & Rudykh, S. Microscopic and macroscopic instabilities in hyperelastic fiber composites. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 99, 471–482 (2017).

Li, Y., Kaynia, N., Rudykh, S. & Boyce, M. C. Wrinkling of interfacial layers in stratified composites. Adv. Eng. Mater. 15, 921–926 (2013).

Li, J., Pallicity, T. D., Slesarenko, V., Goshkoderia, A. & Rudykh, S. Domain formations and pattern transitions via instabilities in soft heterogeneous materials. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807309 (2019).

Chen, X. & Hutchinson, J. W. A family of herringbone patterns in thin films. Scr. Mater. 50, 797–801 (2004).

Chen, X. & Hutchinson, J. W. Herringbone buckling patterns of compressed thin films on compliant substrates. J. Appl. Mech. 71, 597 (2004).

Tran, L. et al. Change in stripes for cholesteric shells via anchoring in moderation. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041029 (2017).

Verwey, G. C., Warner, M. & Terentjev, E. M. Elastic instability and stripe domains in liquid crystalline elastomers. J. Phys. II 6, 1273–1290 (1996).

Finkelmann, H., Kundler, I., Terentjev, E. M. & Warner, M. Critical stripe-domain instability of nematic elastomers. J. Phys. II 7, 1059–1069 (1997).

Song, J. et al. An analytical study of two-dimensional buckling of thin films on compliant substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 014303 (2008).

Li, J. et al. Switching periodic membranes via pattern transformation and shape memory effect. Soft Matter 8, 10322 (2012).

Cha, J. & Daraio, C. Electrical tuning of elastic wave propagation in nanomechanical lattices at MHz frequencies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1016–1020 (2018).

Kuang, X. et al. Advances in 4D printing: Materials and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1805290 (2019).

Rogers, J. A., Someya, T. & Huang, Y. Materials and mechanics for stretchable electronics: From hemispherical imagers to cardiac electrophysiology. Science 327, 1603–1608 (2010).

Kang, S. K. et al. Bioresorbable silicon electronic sensors for the brain. Nature 530, 71–76 (2016).

Lee, J. H. et al. High strain rate deformation of layered nanocomposites. Nat. Commun. 3, 1164 (2012).

Cohen, Y., Albalak, R. J., Dair, B. J., Capel, M. S. & Thomas, E. L. Deformation of oriented lamellar block copolymer films. Macromolecules 33, 6502–6516 (2000).

Makke, A., Perez, M., Lame, O. & Barrat, J. L. Nanoscale buckling deformation in layered copolymer materials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 680–685 (2012).

Acknowledgements

S.R. is grateful for the support of European Research Council (ERC) through Grant No. 852281 - MAGIC. V.S. acknowledges the support of Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC-2193/1–390951807.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., V.S., and S.R. contributed substantially to developing the idea, analysis, and discussion of the results. J.L. led the experimental, numerical, and theoretical aspects of the work. All the authors participated in analyzing the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Slesarenko, V. & Rudykh, S. Emergence of instability-driven domains in soft stratified materials. npj Comput Mater 8, 100 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00783-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00783-x