Abstract

2D spontaneous valley polarization attracts great interest both for its fundamental physics and for its potential applications in advanced information technology, but it can only be obtained from inversion asymmetric single-layer crystals, while the possibility to create 2D spontaneous valley polarization from inversion symmetric single-layer lattices remains unknown. Here, starting from inversion symmetric single-layer lattices, a general design principle for realizing 2D spontaneous valley polarization based on van der Waals interaction is mapped out. Using first-principles calculations, we further demonstrate the feasibility of this design principle in a real material of T-FeCl2. More remarkably, such design principle exhibits the additional exotic out-of-plane ferroelectricity, which could manifest many distinctive properties, for example, ferroelectricity-valley coupling and magnetoelectric coupling. The explored design-guideline and phenomena are applicable to a vast family of 2D materials. Our work not only opens up a platform for 2D valleytronic research but also promises the fundamental research of coupling physics in 2D lattices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Valley pseudospin, characterizing the energy extrema of conduction or valance bands, is an emerging degree of freedom of Bloch electrons in two-dimensional (2D) crystalline solids1,2. Because valleys are largely separated in momentum space, the valley pseudospin is well defined and stable3,4. The manipulation of valley pseudospin for information processing and storage leads to the well-known concept of valleytronics5,6. The main challenge for valleytronics lies in lifting the valley degeneracy, thereby generating valley polarization7,8, and there has been much effort in creating valley polarization, either intrinsic or by extrinsic strategies9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Among them, intrinsic valley polarization presents great and ever-increasing interest, thanks both to its relevance for fundamental physics understanding and its potential technological applications for valleytronics and spintronic devices17.

Physically, there are two essential ingredients for realizing 2D spontaneous valley polarization. One is ferromagnetism with out-of-plane magnetization, and the other is inversion symmetry breaking. Accordingly, the current research on 2D spontaneous valley polarization has been mainly established in the paradigm of inversion asymmetric single layers with ferromagnetism18,19,20,21,22,23. Since inversion asymmetric single-layer semiconductors with ferromagnetism are rare themselves, spontaneous valley polarization is reported in only a few single-layer systems18,19,20,21,22,23. Even for these few existing systems, most of them suffer from the in-plane magnetization in nature that valley polarization disappears, and additional tuning the magnetization orientation from in-plane to out-of-plane is needed18,19,20,23. This poses an outstanding challenge for the field of 2D valleytronics. To overcome this problem, it is of particular importance to go beyond the existing paradigm for creating spontaneous valley polarization.

In this work, on the basis of inversion symmetric single-layer lattices, we theoretically identify a design principle for 2D spontaneous valley polarization through van der Waals interaction. Because of interlayer interaction, antiferromagnetic coupling and out-of-plane electric polarization are admitted simultaneously, which defines spontaneous valley polarization. By means of first-principles calculations, we further predict a real material of T-FeCl2 to establish the feasibility of this design principle. More importantly, we also find this design principle could demonstrate many intriguing phenomena, such as the ferroelectricity-valley coupling and magnetoelectric coupling. These findings provide important insights for the fundamental research in 2D valleytronics as well as coupling physics.

Results and discussion

Design principle for 2D spontaneous valley polarization

Going beyond the existing paradigm of exploring spontaneous valley polarization in inversion asymmetric single-layer systems, our design principle starts from inversion symmetric single-layer lattices with energy extrema of conduction or valance bands located at the K and K′ points. In principle, time-reversal symmetry breaking and inversion symmetry breaking are necessarily required for valley polarization18,22,23. Concerning the first condition, it is generally believed that ferromagnetic coupling is essential. While for antiferromagnetic single layers, valley spin splitting is prohibited because of the protection of antiferromagnetic order, yielding the spin degeneracy for valleys24. Such spin degeneracy limits the anomalous valley Hall effect as well as valleytronic applications. In this regard, we first impose a constraint of ferromagnetism on the single-layer lattices. To satisfy the second condition, van der Waals interaction is further introduced through constructing a bilayer lattice. In bilayer lattice, antiferromagnetism normally dominates interlayer coupling25. For lifting spin degeneracy of valleys, additional constraints should be imposed on the stacking symmetry of the bilayer lattice. Only in this way, 2D spontaneous valley polarization can be realized from inversion symmetric single-layer lattices.

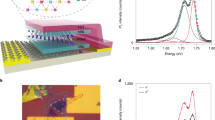

The proposed design principle is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. Considering that magnetic single layers are mainly concentrated on trigonal lattices25, we search through the layer groups and find out two groups with inversion symmetry, see Table 1. Without losing of generality, we assume that the inversion symmetric single layers are ferromagnetic semiconductors with energy extrema of conduction or valance bands located at the K and K′ points. Such trigonal single layers possess a rotation symmetry C3z. By stacking two single layers together, one layer sits on the other with a \((2m - 1)\frac{{\uppi }}{3}\) rotation (m is any nonzero integer). In this case, inversion symmetry is broken in the bilayer lattice. To facilitate the construction of bilayer lattice, the rotation angle is selected as 180°, as shown in Fig. 1a. In detail, for a single layer with a space group \(P\bar 3/P\bar 3m1\), the lower layer can be stacked on the upper layer under the following operation:

Diagrams of a state-IM, b state-I, and c state-II. Left circles in a indicate the magnetization orientations. Schematic diagrams of bands around the K and K′ valleys in d state-IM, e state-I, and f state-II. Blue and yellow cones in d–f corresponds to spin-down bands from the upper and spin-up bands from the lower layers, respectively. g 2D Brillouin zone for bilayer trigonal lattice.

The resultant bilayer system with Mz mirror symmetry is referred to as intermediate state (state-IM). In bilayer lattice, antiferromagnetic coupling normally dominates interlayer exchange interaction25. Once we consider the magnetic space group, state-IM with interlayer antiferromagnetic ordering should break its mirror symmetry \(\hat M_z\) and time-reversal symmetry \(\hat T\). Although both \(\hat M_z\) and \(\hat T\) symmetries are broken, the joint symmetry under time-reversal and mirror reflection \((\hat O \equiv \hat M_z\hat T)\) guarantees the fact that K and K’ valleys remain degenerate in state-IM. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 1d, the K and K’ valleys in state-IM would be energetically degenerate, forbidding spontaneous valley polarization.

To break the \(\hat M_z\hat T\) symmetry, an additional operation \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{1}{3}, - \frac{1}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{2}{3}, - \frac{1}{3},0)\) [Table 1] should be introduced, which results in state-I [Fig. 1b]. In state-I, uncompensated interlayer vertical charge transfer is induced, giving rise to an out-of-plane electric polarization pointing downwards. Also, the magnetic moments distributed on these two constituent single layers would be nonequivalent. In this case, as illustrated in Fig. 1e, spontaneous valley polarization can be realized in the bilayer lattice. In addition, there would be another energetically degenerate stacking configuration [state-II, see Fig. 1c] under the operation \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3}, - \frac{2}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{2}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)\) [Table 1], which exhibits an identical out-of-plane electric polarization but points upwards. In state-II, spontaneous valley polarization occurs as well, and the magnitude of valley polarization is equal to that of state-I; see Fig. 1f. Because the electrostatic potential and electric polarization are reversed, the sign of valley polarization, as well as the spin channel of valleys, are opposite to the case of state-I.

Importantly, the resultant state-I and state-II can be reversibly reversed under interlayer sliding, forming two ferroelectric states. The presence of additional 2D ferroelectricity in the bilayer lattice would lead to many intriguing phenomena. For example, the valley polarization would experience a reversal under ferroelectric switching [see Fig. 1e, f], yielding the ferroelectricity-valley coupling. In detail, along with ferroelectric switching, the spin channel of valleys and the sign of valley polarization are expected to be reversed. It is worth emphasizing that such reversal of valley polarization in inversion asymmetric single layers can only be induced by magnetization effect, which is rather challenging in practice18,20,23. Besides, the imbalanced distribution of magnetic moments would also undergo a reversal upon switching the ferroelectric polarization, suggesting the exotic 2D magnetoelectric coupling.

2D spontaneous valley polarization in bilayer T-FeCl2

Given the design principle, we next discuss its realization in a real material of T-FeCl2. Single-layer (SL) T-FeCl2 with a trigonal lattice (space group \(P\bar 3m1\)) has been predicted to be capable of being exfoliated from its layered bulk26 and recently successfully synthesized27,28. Each unit contains one Fe and two Cl atoms. As shown in Fig. 2c, under the distorted octahedral coordination, the t2g orbitals of Fe atom split into an eg* doublet and a higher-lying a1g singlet orbitals29. The valence electronic configuration of an isolated Fe atom is 3d64s2. In SL T-FeCl2, after donating two electrons to Cl atoms, the left two electrons fill one orbital and four electrons half-fill the other four orbitals, resulting in a formal magnetic moment of 4 µB on each Fe atom and thus spontaneous spin polarization. The magnetic ground state of SL T-FeCl2 is estimated to be ferromagnetism, which is in consistent with the previous work29. Supplementary Fig. 1 displays the band structure of SL T-FeCl2 with SOC, from which we can see the valence band maximum locating at the K points. However, as protected by inversion symmetry, valley physics is absent in SL T-FeCl2.

Crystal structures of bilayer T-FeCl2 in a state-IM, b state-I and state-II. c Crystal field splitting of the Fe-d orbitals. Top panel in c shows the distorted octahedral geometry. d Energy barrier of ferroelectric switching from state-I to state-II. e Spherical plot of MAE arises from rotating the spin axis from the easy axis in bilayer T-FeCl2. The MAE is set to zero in the out-of-plane direction.

Under the operation \(C_{2{{{\mathrm{z}}}}}(0,0,z)\;{{{\mathbf{t}}}}(0,0,{{{\mathbf{t}}}}_0)\), two SL T-FeCl2 are stacked together to construct the state-IM of the bilayer lattice [Fig. 2a], wherein inversion symmetry is broken, but Mz mirror symmetry is formed. Under an additional interlayer sliding of \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{1}{3}, - \frac{1}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{2}{3}, - \frac{1}{3},0)\) state-I of bilayer T-FeCl2 is realized; see Fig. 2b. Its space group is P3m1, hosting neither inversion symmetry nor Mz mirror symmetry. The stability of state-I of bilayer T-FeCl2 is estimated by phonon spectra calculations and molecular dynamic simulations, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Such a stable stacking pattern cannot be directly exfoliated from the layered bulk. In state-I, the Cl3 atom is right below the Cl1 atom, while the Cl2 atom locates directly above the Fe2 atom. Such configuration is expected to raise the separation of positive and negative charge centers along the out-of-plane direction, producing an out-of-plane electric polarization pointing downwards. This is confirmed by the differential charge density and plane averaged electrostatic potential shown in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 3, there is a positive potential discontinuity ΔV = 7 × 10−4 eV between the vacuum levels of the upper and lower layers, which indicates the electric polarization pointing downwards. And from Supplementary Fig. 4, it can be seen that the differential charge density is obviously asymmetric. The electric polarization for state-I is calculated to be −2.7 × 10−3 μC cm−2.

We then investigate the magnetic properties of state-I of bilayer T-FeCl2. By considering different magnetic configurations, our calculations show that the intralayer and interlayer exchange interactions, respectively, are dominated by ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic coupling. This magnetic configuration is energetically stable than the ferromagnetic configuration by 0.8 meV per unit cell, thus it is expected to be observed experimentally under low temperature. It should be noted that due to the existence of electric polarization pointing downwards, the magnetic moment distributed on the Fe atom from the upper layer is slightly larger than that from the lower layer, resulting in a net magnetic moment of 4 × 10−4 µB per unit cell. We also study the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy (MAE) of state-I. Figure 2e illustrates the spherical plot of MAE arising from the rotating spin axis from the out-of-plane direction. The MAE is set to zero in the out-of-plane direction. Obviously, state-I favors out-of-plane magnetization, which is more stable than the in-plane magnetization by 37 meV per unit cell. It is worth emphasizing that such MAE is significantly larger than the values reported in most previous systems with spontaneous valley polarization19,22,23, which is particularly promising for 2D valleytronics.

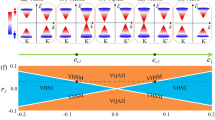

The band structures of state-IM and state-I of bilayer T-FeCl2 with considering SOC are shown in Fig. 3a, b, respectively. For state-IM, it is an antiferromagnetic semiconductor with an indirect bandgap of 2.59 eV. Its conduction band minimum (CBM) lies at the Γ point, and the valence band maximum (VBM) locates at the K and K′ points. Specifically, because of inversion symmetry breaking and antiferromagnetic interlayer coupling, the VBM at the K and K′ points are from the spin-down channel of the upper layer and spin-up channel of the lower layer, respectively. Due to the protection of the joint symmetry of mirror reflection and time-reversal (\(\hat M_z\hat T\)), valley polarization in state-IM is absent. When shifting the Fermi level between the K and K′ valleys and applying an in-plane electric field, the spin-up holes from the K valley and the spin-down holes from the K′ valley would accumulate, respectively, at the left and right sides of the sample, leading to the valley Hall effect, as shown in Fig. 3d. Moreover, the lowest conduction band at the K and K′ points also contributes to two valleys, but being inverted and submerged by the band at the Γ point, which is not applicable for practical applications. We, therefore, focus on the valleys in the highest valence band in the following.

Band structures of a state-IM, b state-I, and c state-II of bilayer T-FeCl2 with considering SOC. Insets in a–c show the enlarged bands around the valleys. The Fermi level is set to 0 eV. Diagrams of the anomalous valley Hall effect or valley Hall effect under hole doping for d state-IM, e state-I, and f state-II. The holes from the K and K′ valleys are denoted by orange + and white + symbols, respectively. Upward and downward arrows refer to the spin-up and spin-down carriers, respectively.

When transferring state-IM to state-I, as shown in Fig. 3b, the indirect gap semiconducting character of bilayer T-FeCl2 is preserved, and the bandgap is found to be 2.60 eV. At the K′ valley, arising from the existence of the electric polarization pointing downwards, the spin-down band from the upper layer shifts above the spin-up band from the lower layer, while the band order at the K valley remains the same as that in state-IM. In this case, despite the antiferromagnetic interlayer coupling, both the K and K′ valleys are from spin-down channels of the upper layer, as shown in Fig. 3b. This is in consistent with the calculated nonzero net magnetic moment. And importantly, the K′ valley is higher than the K valley in energy, lifting the valley’s degeneracy. Accordingly, 2D spontaneous valley polarization is successfully realized in bilayer T-FeCl2. The spontaneous valley polarization for bilayer T-FeCl2 is calculated to be \({\Delta}_{{{{\mathrm{K}}}}\prime - {{{\mathrm{K}}}}} = 5.3\;{{{\mathrm{meV}}}}\). This value is larger than those of the experimentally demonstrated magnetic proximity systems (0.3–1.0 meV)30,31, and is close to those of previously reported doping systems, such as Cr-doped MoSSe (10 meV)32 and Hg-doped MnPSe3 (14 meV)33. By shifting the Fermi level between the K and K′ valleys and applying an in-plane electric field, the anomalous valley Hall effect can be achieved. As shown in Fig. 3e, the spin-up holes from the K′ valley can transversely move to the right side of the sample in state-I. Considering that 2D materials are usually supported by substrates during device fabrication, it is likely that strain will be introduced due to lattice mismatch. To investigate the robustness of the valley feature against strain effect, the biaxial strain is applied on state-I as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The valley properties remain almost unchanged under strain in the range of −3 to 3%, which implies that the valley polarization is robust against the biaxial strain. Moreover, we also modulate the valley polarization by engineering the interlayer distance; see Supplementary Fig. 6. The value of valley polarization in state-I increases monotonically with the decrease of interlayer distance, which is attributed to the enhancement of interlayer interaction.

Based on state-IM, reverse interlayer sliding of \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3}, - \frac{2}{3},0)/{{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{2}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)\) could drive bilayer T-FeCl2 into another energetically degenerate stacking configuration, namely, state-II. In state-II, as shown in Fig. 2b, the Cl3 atom is right below the Fe1 atom, while the Cl2 atom locates directly above the Cl4 atom. This generates an out-of-plane electric polarization pointing upwards. The electric polarization for state-II is calculated to be 2.7 × 10−3 μC cm−2, which is just opposite to that of state-I. Therefore, as expected, state-I and state-II could be considered as two ferroelectric states of bilayer T-FeCl2. We investigated the overall stability of state-I and state-II compared to the other possible stacking patterns of bilayer T-FeCl2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. Note that state-I and state-II have local minimum stacking energies. The ferroelectric reversal pathway is shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. There are six high-symmetry interlayer sliding operations to reverse ferroelectric polarization. Due to the rotation symmetry C3z of bilayer T-FeCl2, under the three equivalent interlayer sliding of \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3}, - \frac{2}{3},0)\), \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{2}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)\) or \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{1}{3},\frac{1}{3},0)\), state-I can be switched to state-II through the paraelectric state [state-PE, inset in Supplementary Fig. 8a]. The switching from state-I to state-II can also be realized by interlayer sliding along the other three equivalent directions [i.e., \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{2}{3},\frac{4}{3},0)\), \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( - \frac{4}{3}, - \frac{2}{3},0)\) or \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}(\frac{2}{3}, - \frac{2}{3},0)\)], which excludes state-PE but includes state-IM. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8b, during the whole process of lateral rigid shifts, state-I and state-II are still the most stable configurations. The switching mechanism is similar to those of the recently reported van der Waals ferroelectrics34,35,36,37,38,39. The state-PE with the space group Abm2 shows no out-of-plane electric polarization due to the existence of a glide plane in the z-direction. The phonon spectra of state-PE displayed in Supplementary Fig. 9 presents pronounced negative frequencies, suggesting that state-PE is unstable and would experience spontaneous transformation into state-I or state-II.

To determine the feasibility of the ferroelectric switching in bilayer T-FeCl2, we investigate the energy barrier employing the nudged-elastic band (NEB) method40. As shown in Fig. 2d, the lowest energy barrier for ferroelectric switching between state-I and state-II is calculated to be 4.2 meV per f.u., which is larger than that of bilayer T′-WTe2 (0.6 meV per f.u.)34, but lower than those of bilayer h-BN (4.5 meV per f.u.)35, bilayer β-GeSe (5.83 meV per f.u.)41 and In2Se3 (66 meV per f.u.)42. This confirms the feasibility of the ferroelectric switching between state-I and state-II.

By switching state-I to state-II, because ferroelectric polarization is reversed, the magnetic moment distributed on the Fe atom from the lower layer is slightly larger than that from the upper layer, which is opposite to the case of state-I. As a consequence, the magnetic properties of bilayer T-FeCl2 can be controlled by ferroelectricity, thereby producing exotic magnetoelectric coupling. In addition to the magnetoelectric coupling, the ferroelectricity-valley coupling is also realized in bilayer T-FeCl2. Figure 3c shows the band structure of state-II. In state-II, the spin orientations for both K and K′ valleys are reversed, namely, from spin-down channels of the upper layer, as shown in Fig. 3c. In state-II, the K′ valley is lower than the K valley in energy. This lifts the valley degeneracy, leading to the 2D spontaneous valley polarization in state-II. The spontaneous valley polarization for state-II is calculated to be \({\Delta}_{{{{\mathrm{K}}}}\prime - {{{\mathrm{K}}}}} = - 5.3\;{{{\mathrm{meV}}}}\), which is opposite to the case of state-I. The anomalous valley Hall effect of state-II of bilayer T-FeCl2 is illustrated in Fig. 3f. With proper hole doping, the spin-down holes from the K valley flow to the left side of the sample under an in-plane electric field, which generates a voltage opposite to the case of state-I. Therefore, the electrical permanent control of valley physics of bilayer T-FeCl2 can be realized by the ferroelectric switching, resulting in the ferroelectricity-valley coupling.

2D spontaneous valley polarization in triple-layer T-FeCl2

From above, we successfully establish a general design principle for spontaneous valley polarization from inversion symmetric single layers. Actually, this design principle is also applicable for multilayer lattices. Here, we take triple-layer T-FeCl2 as an example to address it. Starting from AAA stacking pattern, interlayer sliding \({{{\mathbf{t}}}}( \!\mp\! \frac{1}{3}, \pm\! \frac{1}{3},0)\) of the top or bottom layer can break the inversion symmetry as well as Mz mirror symmetry, leading to state-I or state-II of triple-layer T-FeCl2, as shown in Fig. 4a. The out-of-plane electric polarizations for state-I and state-II are calculated to be 5.4 × 10−3 and −5.4 × 10−3 μC cm−2, respectively. These two states are ferroelectric states of triple-layer T-FeCl2, which can be reversed under a relative interlayer sliding of the middle layer. The energy barrier for transferring state-I to state-II is calculated to be 26.8 meV per f.u. Although such barrier is higher than that of the bilayer case, it is still much lower as compared with traditional ferroelectrics43,44. Akin to the case of bilayer T-FeCl2, the inequivalent magnetic moment distribution for state-I is opposite to state-II, which correlates to the opposite electric polarization. This yields magnetoelectric coupling in triple-layer T-FeCl2 as well. Figure 4b, c present the band structures of state-I and state-II with considering SOC, respectively. For both cases, 2D spontaneous valley polarization is successfully achieved. In state-I, the K and K’ valleys are from spin-down channels of the bottom layer [Fig. 4b], and the K′ valley is higher than the K valley in energy, generating a valley polarization of 4.7 meV. While in state-II, as shown in Fig. 4c, the K and K′ valleys are from spin-down channels of the top layer, and the K′ valley is lower than the K valley in energy, leading to a valley polarization of −4.7 meV. In this regard, when shifting the Fermi level between the K and K′ valleys and applying an in-plane electric field, the spin-up holes from the K′ and K valleys will accumulate at the same side of the sample in the state-I and state-II, leading to the anomalous valley Hall effect. As a consequence, 2D spontaneous valley polarization and magnetoelectric coupling can be obtained in triple-layer FeCl2 as well.

a Crystal structures triple-layer T-FeCl2 under state-I and state-II. Band structures of b state-I and c state-II of triple-layer T-FeCl2 with considering SOC. Insets in b, c show the enlarged bands around the valleys. The Fermi level is set to 0 eV. Diagrams of the anomalous valley Hall effect under hole doping for d state-I and e state-II. The holes from the K and K′ valleys are denoted by orange + and white + symbols, respectively. Upward arrows refer to the spin-up carriers.

At last, we wish to stress that such 2D spontaneous valley polarization induced by interlayer translation and rotation from inversion symmetric lattices is predicted to exist widely in many other van der Waals systems, such as CrF3, T-CoCl2 and T-CoBr2, etc., as these ferromagnetic single-layers exhibit the space group \(P\bar 3/P\bar 3m1\) similar to T-FeCl2 and possess the energy extrema of conduction or valance bands at the K and K′ points as well28,45.

In conclusion, we introduce a general design principle for 2D spontaneous valley polarization from inversion symmetric lattices and predict a real material to realize it. Moreover, this design principle exhibits the exotic out-of-plane ferroelectricity, which could demonstrate many distinctive properties, for example, ferroelectricity-valley coupling and magnetoelectric coupling. Our work greatly enriches the physics and expands the family of 2D spontaneous valley polarization, which is expected to draw immediate experimental interest.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

First-principles calculations are performed based on density functional theory46 as implemented in Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)47. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the form of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)48 is applied. Structures are fully relaxed until the force on each atom is less than 0.02 eV Å−1, and the electronic iteration convergence criterion is set to 10−5 eV. A Monkhorst–Pack k-point mesh of 15 × 15 × 1 is used to sample 2D Brillouin zone. The vacuum space of at least 20 Å is introduced to avoid spurious interactions between neighboring sheets. The cutoff energy is set to 450 eV. Grimme’s DFT-D3 method is employed for taking van der Waals interaction into account49. According to previous work50, we use the GGA + U approach with Ueff = (U − J) = 4.0 eV for Fe-d orbitals, but it is not included in the structural optimization. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation is performed to examine the thermal stability at 500 K for 5 ps with a time step of 1 fs51. The calculation of phonon dispersion is based on a supercell approach using PHONOPY code52. The energy barrier of ferroelectric switching is investigated using the nudged-elastic band (NEB) method40. The ferroelectric polarization is evaluated using the Berry phase approach53, and the dipole correction is used to meet the convergent criterion54.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The central codes used in this paper are VASP. Detailed information related to the license and user guide are available at https://www.vasp.at.

References

Mak, K., McGill, K., Park, J. & McEuen, P. The valley Hall effect in MoS2 transistors. Science 344, 1489 (2014).

Wu, S. et al. Electrical tuning of valley magnetic moment through symmetry control in bilayer MoS2. Nat. Phys. 9, 149 (2013).

Lu, H.-Z., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Shen, S. Intervalley scattering and localization behaviors of spin-valley coupled dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 016806 (2013).

Berkelbach, T., Hybertsen, M. & Reichman, D. Theory of neutral and charged excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 88, 045318 (2013).

Xiao, D., Yao, W. & Niu, Q. Valley-contrasting physics in graphene: magnetic moment and topological transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 236809 (2007).

Xiao, D., Liu, G.-B., Feng, W., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Coupled spin and valley physics in monolayers of MoS2 and other group-VI dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 196802 (2012).

Zhang, Q., Yang, S., Mi, W., Cheng, Y. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Large spin-valley polarization in monolayer MoTe2 on top of EuO(111). Adv. Mater. 28, 959–966 (2016).

Zeng, H., Dai, J., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Cui, X. Valley polarization in MoS2 monolayers by optical pumping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 490 (2012).

Cheng, Y., Zhang, Q. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Valley polarization in magnetically doped single-layer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 89, 155429 (2014).

Singh, N. & Schwingenschlögl, U. A route to permanent valley polarization in monolayer MoS2. Adv. Mater. 29, 1600970 (2017).

Aivazian, G. et al. Magnetic control of valley pseudospin in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 148 (2015).

MacNeill, D. et al. Breaking of valley degeneracy by magnetic field in monolayer MoSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 037401 (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Large valley splitting in monolayer WS2 by proximity coupling to an insulating antiferromagnetic substrate. Phys. Rev. B 97, 041405 (2018).

Zhang, H., Yang, W., Ning, Y. & Xu, X. Abundant valley-polarized states in two-dimensional ferromagnetic van der Waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 101, 205404 (2020).

Zhong, D. et al. Van der Waals engineering of ferromagnetic semiconductor heterostructures for spin and valleytronics. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603113 (2017).

Hu, T. et al. Manipulation of valley pseudospin in WSe2/CrI3 heterostructures by the magnetic proximity effect. Phys. Rev. B 101, 125401 (2020).

Schaibley, J. et al. Valleytronics in 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16055 (2016).

Tong, W., Gong, S., Wan, X. & Duan, C. Concepts of ferrovalley material and anomalous valley Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 1 (2016).

Cui, Q., Zhu, Y., Liang, J., Cui, P. & Yang, H. Spin-valley coupling in a two-dimensional VSi2N4 monolayer. Phys. Rev. B 103, 085421 (2021).

Cheng, H., Zhou, J., Ji, W., Zhang, Y. & Feng, Y. Two-dimensional intrinsic ferrovalley GdI2 with large valley polarization. Phys. Rev. B 103, 125121 (2021).

Zhang, C., Nie, Y., Sanvito, S. & Du, A. First-principles prediction of a room-temperature ferromagnetic Janus VSSe monolayer with piezoelectricity, ferroelasticity, and large valley polarization. Nano Lett. 19, 1366 (2019).

Zhao, P. et al. Single-layer LaBr2: two-dimensional valleytronic semiconductor with spontaneous spin and valley polarizations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 261605 (2019).

Peng, R. et al. Intrinsic anomalous valley Hall effect in single-layer Nb3I8. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035412 (2020).

Li, X., Cao, T., Niu, Q., Shi, J. & Feng, J. Coupling the valley degree of freedom to antiferromagnetic order. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 3738 (2013).

Guo, Y. et al. Magnetic two-dimensional layered crystals meet with ferromagnetic semiconductors. InfoMat 2, 639–655 (2020).

Kulish, V. & Huang, W. Single-layer metal halides MX2 (X = Cl, Br, I): stability and tunable magnetism from first principles and Monte Carlo simulations. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 8734 (2017).

Cai, S., Yang, F. & Gao, C. FeCl2 monolayer on HOPG: art of growth and momentum filtering effect. Nanoscale 12, 16041–16045 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. Atomically thin 1T-FeCl2 grown by molecular-beam epitaxy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 9416–9423 (2020).

Botana, A. S. & Norman, M. R. Electronic structure and magnetism of transition metal dihalides: bulk to monolayer. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 044001 (2019).

Seyler, K. et al. Valley manipulation by optically tuning the magnetic proximity effect in WSe2/CrI3 heterostructures. Nano Lett. 18, 3823–3828 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Ni, X., Huang, H., Hu, L. & Liu, F. Valley splitting in the van der Waals heterostructure WSe2/CrI3: the role of atom superposition. Phys. Rev. B 99, 115441 (2019).

Peng, R., Ma, Y., Zhang, S., Huang, B. & Dai, Y. Valley polarization in Janus single-layer MoSSe via magnetic doping. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 3612–3617 (2018).

Pei, Q., Wang, X., Zou, J. & Mi, W. Half-metallicity and spin-valley coupling in 5d transition metal substituted monolayer MnPSe3. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 8092–8098 (2018).

Yang, Q., Wu, M. & Li, J. Origin of two-dimensional vertical ferroelectricity in WTe2 bilayer and multilayer. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 7160 (2018).

Li, L. & Wu, M. Binary compound bilayer and multilayer with vertical polarizations: two-dimensional ferroelectrics, multiferroics, and nanogenerators. ACS Nano 11, 6382–6388 (2017).

Fei, Z. et al. Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336 (2018).

Stern, M. et al. Interfacial ferroelectricity by van der Waals sliding. Science 372, 1462–1466 (2021).

Yasuda, K., Wang, X., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Stacking-engineered ferroelectricity in bilayer boron nitride. Science 372, 1458–1462 (2021).

Liang, Y. et al. Out-of-plane ferroelectricity and multiferroicity in elemental bilayer phosphorene, arsenene, and antimonene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 012905 (2021).

Mills, G., Jónsson, H. & Schenter, G. Reversible work transition state theory: application to dissociative adsorption of hydrogen. Surf. Sci. 324, 305–337 (1995).

Guan, S., Liu, C., Lu, Y., Yao, Y. & Yang, S. Tunable ferroelectricity and anisotropic electric transport in monolayer β-GeSe. Phys. Rev. B 97, 144104 (2018).

Ding, W. et al. Prediction of intrinsic two-dimensional ferroelectrics in In2Se3 and other III2-VI3 van der Waals materials. Nat. commun. 8, 14956 (2017).

Zhong, T., Ren, Y., Zhang, Z., Gao, J. & Wu, M. Sliding ferroelectricity in two-dimensional MoA2N4 (A = Si or Ge) bilayers: high polarizations and Moiré potentials. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 19659–19663 (2021).

Ma, X., Liu, C., Ren, W. & Nikolaev, S. Tunable vertical ferroelectricity and domain walls by interlayer sliding in β-ZrI2. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 177 (2021).

Zhang, W.-B., Qu, Q., Zhu, P. & Lam, C.-H. Robust intrinsic ferromagnetism and half semiconductivity in stable two-dimensional single-layer chromium trihalides. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 12457 (2015).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456 (2011).

Liu, C., Zhao, G., Hu, T., Bellaiche, L. & Ren, W. Structural and magnetic properties of two-dimensional layered BiFeO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 103, L081403 (2021).

Barnett, R. & Landman, U. Born-Oppenheimer molecular-dynamics simulations of finite systems: structure and dynamics of (H2O)2. Phys. Rev. B 48, 2081 (1993).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 134106 (2008).

King-Smith, R. & Vanderbilt, D. Theory of polarization of crystalline solids. Phys. Rev. B 47, 1651 (1993).

Shirodkar, N. & Waghmare, U. Emergence of ferroelectricity at a metal-semiconductor transition in a 1T monolayer of MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 157601 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12074217), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. ZR2019QA011 and ZR2019MEM013), Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Major Scientific and Technological Innovation Project) (No. 2019JZZY010302), Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (No. 2019RKE27004), Shandong Provincial Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars (No. ZR2020YQ04), Qilu Young Scholar Program of Shandong University, and Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z. and X.X. performed calculations and data analysis. Y.M. supervised the project. T.Z. and Y.M. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Xu, X., Huang, B. et al. 2D spontaneous valley polarization from inversion symmetric single-layer lattices. npj Comput Mater 8, 64 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00748-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00748-0

This article is cited by

-

A first-principles study of bilayer 1T'-WTe2/CrI3: a candidate topological spin filter

npj Spintronics (2024)

-

High-throughput computational stacking reveals emergent properties in natural van der Waals bilayers

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Research progress on 2D ferroelectric and ferrovalley materials and their neuromorphic application

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)