Abstract

Materials innovation calls for an integrated framework combining physics-based modelling and data-driven informatics. A dislocation-based constitutive model accounting for both transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) was built to interpret the mechanical characteristics of metastable titanium alloys. Particular attention was placed on quantitatively understanding the composition-sensitive phase stability and its influence on the underlying deformation mechanism. For this purpose, a pseudoelastic force balance incorporating thermodynamics and micromechanics was applied to calculate the energy landscapes of β → α″ martensitic transformation, {332}〈113〉 twinning and dislocation slip. Extensive material data were probed, computed and fed to the model. Our results revealed that TRIP and TWIP may operate simultaneously because of the presence of a noticeably overlapped energy domain, and confirmed {332}〈113〉 twinning is an energetically favourable deformation mechanism. The model validation further unveiled that the activation of β → α″ transition remarkably enhances the strain-hardening and plasticity, even though the dynamically formed α″ volume fraction is much less than that of deformation twinning. Our work suggests that the synchronised physical metallurgy and data-driven strategy allows to identify the compositional scenarios for developing high-performance engineering alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aerospace sector plays a significant role in driving materials innovation1. Approximately one-third of the structural weight of modern turbine engines is made up of Ti alloys2, thanks to their excellent integrity of high specific strength, corrosion resistance and good stability to the elevated temperatures. Ti alloys with transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and/or twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) effects have been showing superior toughness and ductility3. The enhanced damage-tolerance is especially important for the highest safety-critical aeroengine components, which is able to resist catastrophic crack growth and allows time for inspection. However, the TRIP/TWIP and TWIP Ti alloys are not fully exploited for engineering applications, and it requires a thorough understanding of the underlying deformation mechanisms. This necessitates a comprehensive strategy incorporating a selection of composition, microstructure and processing parameters to quantitatively capture the materials information and mechanical response. Here the term TRIP/TWIP designates simultaneous activation of strain-induced martensitic transformation and deformation twinning, whereas TWIP refers only twinning is operative.

The strain-transformable Ti alloys present excellent plasticity (i.e. uniform elongation (uEL)) via pronounced strain-hardening. For determining the property, it is critical to quantify the rate at which the critical stress evolves over strain or, equivalently, the rate at which dislocations accumulate under strain4. This is performed through modelling a key quantity, dislocation mean free path, which is the distance travelled by a dislocation segment before it is stored by the interaction with the microstructure features, such as dislocation forest. The mean free path is reduced as strain increase and may be interrupted by the transformation products of TWIP and TRIP. Furthermore, deformation twinning and martensitic transformation create extra shear to accommodate the strain increase. {332}〈113〉 twinning is a featured and widely exist twinning system in bcc (body-centred cubic) β Ti alloys, which produces \(\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}}\) shear strain and the rest atoms are transferred by shuffling. Meanwhile, β phase may transform to α″ martensite (C-orthorhombic) with the assistance of external load, and the crystal structure of α″ is intermediate between bcc and hcp (hexagonal close packed). TRIP and TWIP deformation modes may undergo simultaneously because the mechanisms of martensitic transformation and deformation twinning are intrinsically analogous. A deformation twin is produced by a homogeneous shear of the lattice parallel to the twinning (habit) plane; whereas martensitic transformation occurs not only by a shear parallel to the habit plane, but also together with a small dilatation normal to the plane5. The analogy is also reflected on the dislocation mechanisms of martensite and twin nucleation. For instance in fcc (face-centred cubic) alloys, ε martensite nucleates by the arrangement of intrinsic stacking faults on every second {111} plane, whereas twins nucleates by overlapping three stacking faults on successive planes; stacking faults typically form by the dissociation of \(\frac{1}{2}\{111\}\langle 110\rangle\) dislocations into \(\frac{1}{6}\{111\}\langle 112\rangle\) Shockley partials. However, the dislocation mechanism of {332}〈113〉 twinning or orthorhombic α″ martensite is lack of a thorough understanding; there is few theoretical method considering both transitions synthetically.

The purpose of this work is twofold. First, a dislocation-based constitutive model is built for TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys to interpret the microstructural evolution led by β → α″ martensitic transformation and {332}〈113〉 twinning. The TRIP/TWIP model was tested in a wide range of alloys, and further compared with the previous TWIP model6 in order to explicitly clarify the TRIP contribution to stain-hardening. Second, we aim to quantitatively understand the composition-dependent phase stability and its influence on deformation modes. A pseudoelastic model incorporating thermodynamics and micromechanics was applied to calculate the threshold energy of each transformation. Extensive material information was collected and fed to the algorithm for revealing the composition sensitivity. A comprehensive computational framework is developed to link alloy composition, strengthening mechanism and mechanical response of TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys.

Results

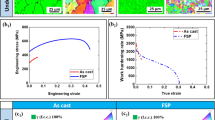

TRIP/TWIP alloys and deformation characteristics

Table 1 summarises the compositions, deformation mechanisms and mechanical properties of TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys. Figure 1a comparatively visualises strain-hardening vs. uEL over three major groups of Ti alloys i.e. undergoing TRIP/TWIP, TWIP or dislocation slip. The strain-hardening accounts for the difference between the ultimate tensile stress (UTS) and the yield stress (σY). uEL is applied to describe the tensile plasticity and the value is approximated by the Considère criterion7. The targeting mechanical properties in the perspective of alloy design are to achieve over 300 MPa in strain-hardening meanwhile preserving more than 0.3 in uEL8. Most of TRIP/TWIP alloys’ uELs lie in the range between 0.3 and 0.36, whereas for TWIP alloys the number falls to 0.16 and 0.24. Stabilised β alloys or α + β alloys show negligible uEL due to the lack of strain-hardening9. The TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys present the best combined mechanical properties and some strain-hardening went beyond 340 MPa, while the hardening decreases to 100–300 MPa in TWIP alloys.

Many modern TRIP/TWIP and TWIP Ti alloys were successfully discovered with the guidance of the Bo – Md map in Fig. 1b. The electronic parameters Bo (bond order) and Md (metal d-orbital energy level) of each element were determined by first-principle calculations (DV-Xα molecular orbital method)10, whereas the mean electronic parameters of the alloy were simply approximated from the compositional average11,12. Nevertheless for complex multicomponent systems, this approximation is difficult to prescribe the electronic state reasonably. The dashed lines indicate empirical borders based on a small dataset11, which divide the map into α, α + β and β phase regions and aid in distinguishing different deformation modes. This simple mapping approach shows its efficiency in alloy design8. We calculated the Bo and Md values of the major TRIP/TWIP and TWIP Ti alloys, then placed them onto the plot in Fig. 1b. These alloys with main alloying elements Mo, Cr and V group at two regions in the Bo – Md diagram as highlighted. However, future alloy development may not be limited to these regions. For example, one may develop sustainable and low-cost alloys, while preserving desired mechanical properties.

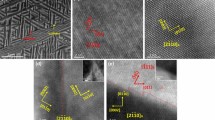

Microstructural evolution and mechanical response

A dislocation-based constitutive model was built to describe the simultaneous activation of TRIP and TWIP effects, and the detailed methodology is described in the “Methods” section. The model was validated by the alloys in Table 1, where the tensile deformation was subjected to quasi-static strain rates at room temperature. Figure 2 shows the model validation in Ti-12Mo. The experimental data of α″ martensite volume fraction (Fig. 2a) were adopted from Cho et al.13 by in situ neutron diffraction. Both α″ martensite and twinning were activated at the onset of critical strain (εT = 0.013). The growing rate of ftw was significantly higher than that of fα″ at early stage of plastic deformation. Figure 2b represents the total dislocation density ρ raised from an initial value of 7.3 × 1013 till 4.6 × 1015 m−2. The dislocation accumulation was significantly promoted by the reduced mean free path from early to intermediate deformation stage. Eventually the rise was suppressed by dynamic recovery at late stage due to the dislocation annihilation. The experimental stress-strain curve in Fig. 2c was adopted until the onset of necking. The modelled flow stress is in reasonably good agreement with the experimental result. For comparison, a virtual flow stress curve (dash curve) subtracting TRIP effect was predicted using the same set of parameters. It displayed considerable strain-hardening although a decreased UTS was reached. Such mechanical behaviour is fairly comparable to that of Ti-15Mo14 or Ti-10Mo-1Fe alloys15, where only TWIP deformation mode was operated.

a The growth of {332}〈113〉 twin and α″ martensite volume fraction (ftw and fα″, respectively) at the onset of critical strain. The error bars on twin fraction were adopted from the experimental measurement13. b The evolution of total dislocation density. c The experimental and modelled flow stress. The dash curve predictively illustrates the flow stress without TRIP contribution.

Figure 3 shows the model validation in Ti-10V-4Cr-1Al, a TRIP/TWIP alloy with ultra-high strain-hardening effect developed by Lilensten et al.16 in which α″ volume fraction was measured using in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction. The α″ martensite formed at the onset of critical strain and fα″ increased rapidly to accommodate the strain. The growth of ftw was predicted by incorporatively depicting the rise of fα″ and strain-hardening. The model well reflected the microstructural evolution and projected the experimental stress-strain curve. The strain-hardening decreased when TRIP effect was subtracted (dash curve in Fig. 3c), indicating around 300 MPa at UTS was attributed to TRIP in Ti-10V-4Cr-1Al. This outcome corresponds to the rapid increase of fα″ at the early deformation stage and the subsequent higher α″ fraction.

a The growth of twin and martensite volume fraction over strain. The error bars on martensite fraction were adopted from the experimental measurement16. b The increase of total dislocation density. c The experimental and modelled stress-strain curves, where the dash curve illustrates the flow stress subtracting TRIP effect.

The model was tested in a wider range of alloys, such as Ti-7Mo-3Cr17, Ti-8.5Cr-1.5Sn18 and Ti-9Mo-6W19, Ti-3Mo-3Cr-2Fe-1Al20, Ti-8Mo-16Nb21, Ti-12Mo-5Zr22 and Ti-7V-5Mo-3Cr-3Al23. The difference in strain-hardening was reflected on the growing rate of ftw and fα″ (Fig. 4). The alloys with lower phase stability tend to display increased transition kinetics, which is facilitated by the easy nucleation of deformation products. It is known that transformation kinetics is also sensitive to external deformation conditions, e.g., strain rate and temperature, in which reduced strain rate or elevated temperature may inhibit the transformation24. Given by the experiments were operated within a narrow range of \(\dot{\varepsilon }\) (4.0 × 10−4 − 1.0 × 10−3 s−1) at room temperature, in this case the kinetics was solely influenced by the intrinsic phase stability. Table 2 shows the material parameters of the tested alloys. While the values of Ftw and Fα″ were almost preserved constantly, the deference in strain-hardening was governed by two internal variables: twinning and martensitic transformation kinetics parameters (βtw and βα″). In the following subsection, the composition-sensitive deformation mechanisms are evaluated.

a The predicted evolution of twin volume fraction ftw (solid curves) and α″ volume fraction fα″ (dash curves) in Ti-7Mo-3Cr, Ti-8.5Cr-1.5Sn, Ti-9Mo-6W, Ti-3Mo-3Cr-2Fe-1Al, Ti-8Mo-16Nb, Ti-12Mo-5Zr and Ti-7V-5Mo-3Cr-3Al alloys. b The modelled flow stresses reasonably well agree to the experimental data.

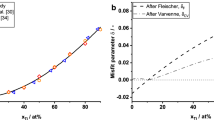

Energy landscape of TRIP and TWIP

Extensive material data were collected and analysed by the pseudoelastic model to determine the energy landscape of TRIP, TWIP and dislocation slip. The current investigation not only covers laboratory-developed TRIP/TWIP and TWIP alloys, but also includes commercial or semi-commercial β-Ti alloys. The information including composition, mechanical property and operative deformation mode was constituted as a comprehensive dataset. The Gibbs free energy difference ΔGβ→α at ambient temperature was calculated using TCTI2:Ti alloys thermodynamic database25 developed by Thermo-Calc AB. Table 3 lists the input parameters, i.e., Gibbs free energy change, yield stress, elastic strain energy and frictional stress, as well as the output energy landscape. Figure 5 visualises the variation of energy landscape ΔΓ vs. the Gibbs energy difference ΔGchem. The alloys can be divided into three groups according to their deformation modes, and each group shows a distinctive ΔΓ energy domain. TRIP/TWIP alloys locate in the ΔΓ region of 0–1100 J mol−1, whereas TWIP alloys distribute in a wider range of −500–830 J mol−1. A noticeable overlapping area between TRIP/TWIP and TWIP alloys (0–830 J mol−1) is shown, revealing that the deformation twinning and β → α″ martensitic transformation are mutually inclusive and the β → α″ transformation may be activated jointly in the TWIP alloys of this area. The high ΔΓ domain (830–1100 J mol−1) suggesting the driving force is much higher than the opposing one, which alloys are rather metastable that β → α″ can be easily triggered with the aid of stress. The TWIP only region (−500–0 J mol−1) is associated with the increased β-stability, where β → α″ can hardly take place because the transformational resistance is too high to overcome. β-phase is fully stabilised and the alloys only undergo dislocation slip as ΔΓ ≤ 510 J mol−1. It is worth noting that some of the alloys violate the model predictions. These alloys can be categorised into three types. First, alloy no. 20, Ti-4Mo-3Cr-1Fe, is located in the deep TRIP/TWIP region and showed typical TRIP/TWIP mechanical characteristics, such as hump-shaped strain-hardening rate over strain. Interestingly, α″ martensite was not identified by the ex situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observations26. TEM can only observe very localised areas, besides α″ martensite may easily revert to the β-matrix after stress release. Second, alloy No. 11, 36, 24, 25 are located close to the Slip/TWIP boundary, indicating the phase stabilities of these alloys accommodate in the vicinity of stable/metastable interface. It suggests that a transition zone may exist between the energy landscapes of Slip and TWIP. Besides, these alloys are more sensitive to deformation conditions, e.g. strain rate and temperature. Third, alloy no. 10 and 50 (Ti-8Mo-16Nb and Ti-7V-5Mo-3Cr-3Al) display TRIP/TWIP characteristics as revealed by experiments21,23, but fall into the TWIP region due to low ΔΓ. Ti-8Mo-16Nb shows significantly decreased chemical driving force compared to other TRIP/TWIP alloys due to the relatively higher Nb content. Nb plays an important role in stabilising the β phase in the TCTI2:Ti database25. On the other hand, Ti-7V-5Mo-3Cr-3Al exhibited a small amount of α″ martensite as revealed by the experiments, which indicates that the β → α″ transition was suppressed due to insufficient transformational driving force. Overall, it is possible to predict the potential deformation mode of a given composition according to the energy landscape map.

The alloys were labelled corresponding to the number in Table 3. A clear boundary was identified between the stabilised β-alloy and the metastable alloys. The energy domains of TWIP alloys and TRIP/TWIP alloys exhibit large overlapping area, suggesting deformation twinning and strain-induced martensite are mutually inclusive for most of the compositions in this region.

Discussion

The goal of this work is to build a comprehensive connection of materials information and the mechanical response of TRIP/TWIP alloys. A further important aspect is that the extensive data of Ti alloys undergoing dislocation slip, TWIP or hybrid TRIP/TWIP were analysed and fed to the pseudoelastic algorithm. Each deformation mode exhibits distinctive domain in terms of the transformational energy landscape. Within this framework, a dislocation-based constitutive model was built to interpret the origin of the exceptional strain-hardening by unveiling the evolution of α″ martensite and {332}〈113〉 twin. The excellent combination of plasticity and strain-hardening stems from the reduced dislocation mean free path via the synchronous activation of TRIP and TWIP, as well as from the backstress generated by dislocation pile-up at obstructive interfaces.

The phase stability of Ti alloys corresponding to specific deformation mechanism necessitates a quantitative evaluation. Although the assessment of the chemical driving force may offer a rough guidance that alloys trend to be stabilised with lower Gibbs free energy difference, it can hardly provide explicit energy domains that identity different deformation modes. As suggested by Yan and Olson27, the current treatment unifies the orthorhombic α″ martensite and the hcp \(\alpha ^{\prime}\) phase in terms of the thermodynamics. Given by the orthorhombic α″ has a crystal structure intermediate between bcc and hcp, it is reasonable to describe the β → α″ transformation as a crystallographically incomplete \(\beta \to \alpha ^{\prime}\) transformation that should have a smaller transformation enthalpy change. Although the difference between orthorhombic and hcp was not considered in the thermodynamic computation, it was reflected through the elastic strain energy. Another interesting phenomenon is that {332}〈113〉 twinning widely exists in almost all the metastable Ti alloys, which is understood by its energetically essential characteristics.

In summary, an integrated framework was developed combining physics-based modelling and data-driven informatics, which effectively links composition, mechanical response and the underlying deformation mechanism. The model takes explicitly into account the microstructural evolution by synthetically describing the martensitic transformation and deformation twinning. The flow stress incorporates the enhanced isotropic hardening by emerging obstacles and the kinematic hardening from backstress. The modelling outcome reasonably well agrees to the experimental data. Moreover, the mechanical behaviours can be captured using a set of physically motivated parameters. TRIP and TWIP modes may operate simultaneously because of the existence of a noticeably overlapped domain in threshold energy, which further indicates β → α″ transformation and {332}〈113〉 twinning are mutually inclusive. Besides, the low shear strain of {332}〈113〉 twin makes it an energetically essential deformation mechanism for metastable Ti alloys. Our work suggests that the synchronised physical metallurgy and data-driven strategy provides an effective tool for TRIP/TWIP alloy design. Furthermore, the computational methodology shows flexible compatibility to a broad range of strain-transformable alloys, e.g., austenitic steels, Cu and high entropy alloys, meaning it may potentially serve and benefit multiple industrial sectors.

Methods

Threshold energy for transformation

β → α″ martensitic transformation is facilitated by chemical driving force (Gibbs free energy difference between parent and product phases) and triggered by mechanical work. A martensitic embryo of a given volume tends to adopt a shape by minimising the combined interfacial and elastic strain energies. In the case of a thin martensite ellipsoidal inclusion with radius a and semi-thickness c, the overall energy barrier associated to the formation of a coherent nucleus is5,28:

Δgstr the volumetric elastic strain energy and Δgchem the volumetric chemical driving force; γ0 the interfacial energy per unit area of a martensitic nucleus; τT and γT the critical resolved shear stress and shear strain at the onset of transformation, respectively.

Martensitic transformation occurs by a homogeneous shear parallel to the habit plane together with a small dilatation normal to the plane, where complete coherency is maintained at the interface29. Thus the elastic strain energy Δgstr is divided into a shear-induced shape change \({{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{shear}\) and a dilatational volume change \({{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{dila}\) with: \({{\Delta }}{g}_{str}\,=\,{{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{dila}\,+\,{{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{shear}\)30. The shape change is approximated by pure shear and described as5,31:

where s the shear component, ν the Poisson’s ratio and μ the shear modulus at ambient temperature. Here, the composition-dependent shear modulus of β Ti alloys was calculated by means of the rule of mixture following Galindo-Nava et al. and Toda-Caraballo et al.32,33, i.e., for isotropic polycrystal metals μ = μ0 + ∑i(μi − μ0)Xi. μ0 = 37.5 ± 1.5 GPa the shear modulus of pure Ti, Xi the atomic fraction of element i, and μi the shear modulus of element i. The latter is available from ref. 34. The calculated shear moduli of β alloys are approximated as μ = 40 ± 3 GPa, and the predicted properties, such as flow stress and transformational threshold energy are weakly influenced by the variation of shear modulus. The Poisson’s ratio lies in a relativity narrow range for bcc Ti alloys and ν = 0.32 ± 0.01 was adopted35. On the other hand, the dilatational strain energy caused by volume change comes from Eshelby’s elastic field theory of an ellipsoidal inclusion embedded in an infinite elastically isotropic matrix31:

The dilatation \(\frac{{{\Delta }}V}{V}\) of β → α″ transition can be calculated using a molar-volume assessment36:

where \({V}_{m}^{\phi }\) is the molar volume (m3 mol−1) of phase ϕ (α″ or β) and its value can be calculated by a linear combination of pure elements plus a regular-solution model for the excess volume36:

Xi and Xj denote the molar fraction of solute i and solvent j, respectively. \({{{\Omega }}}_{i,j}^{\phi }\) the molar volume interaction parameter between solute i and the solvent.

The martensite growth mainly results from the competition between elastic strain energy and transformational driving force. Before the applied stress τ reaches the critical revolved shear stress τT, no transition takes place and full β phase is retained. As the load increasing and once the nucleation barrier has been overcome, the chemical volume free energy term becomes so large that the martensite plate grows radially (∂ΔG/∂a < 0) until it hits a strong obstacle (e.g. grain boundary or twin interface). From that point, the plate starts to thicken in the direction normal to the habit plane (∂ΔG/∂c < 0), until it achieves a state that the growth does not allow the system to further reduce its energy and a mechanical equilibrium (∂ΔG/∂c = 0) is reached28. Combining Eqs. (1), (2) and (3) and differentiating energy barrier ΔG with respect to c, the equilibrium becomes:

The above pseudoelastic force balance can be simplified as \({{\Delta }}{g}_{chem}\,+\,{\tau }_{T}{\gamma }_{T}\,=\,{{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{dila}\,+\,2{{\Delta }}{g}_{str}^{shear}\). The current equilibrium represents an ideal energy balance in plate growth and reversal, where the transformation strain is elastically accommodated and there is no frictional resistance on the transformational interface. A frictional shear stress τf acting to oppose the transition should be included, where the net driving force for transformation is effectively reduced by the term τfγT. Thence the force balance becomes:

The frictional stress is generated by the interactions between dislocation motion and solid solution; such effect was expressed by means of solid solution hardening \({\tau }_{f}\,=\,\mu {\lambda }^{4/3}{X}_{i}^{2/3}Z\),where λ a misfit parameter accounting for both lattice parameter misfit and the shear modulus misfit between solute and solvent, Z a temperature-dependent numerical factor whose value can be obtained from a plot of \(d\tau /d{X}_{i}^{2/3}\)vs. λ4/334. The frictional resistance term becomes positive when the plate is thickening and negative when it reverts.

In order to capture the threshold energy to trigger martensitic transformation, the energy landscape ΔΓ is defined to describe the energy margin between the transformational driving force and the resistance:

The martensitic transformation is operative when ΔΓ > 0 because the combined driving force (i.e. Gibbs energy difference and external mechanical work) is larger than the transition resistance (i.e. elastic strain energy and frictional stress)37. A flow chart in Fig. 6 illustrates the calculation approach. The inputs include alloy composition, macroscopic yield stress and grain size. The molar Gibbs energy difference can be obtained from a thermodynamic database. In TRIP/TWIP alloys, the radius of martensitic inclusion a initially equals to the radius of the grain size and it shrinks by the dynamically reduced intertwin space. c is the minimal detectable semi-thickness of a martensitic plate and c = 60 ± 10 nm is adopted17.

Constitutive model for TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys

A dislocation-based model was build integrating the simultaneous activation of TRIP and TWIP effects. In this case, the increment of macroscopic strain dε is not only mediated by dislocation glide dεdis, but also accommodated by twinning and β → α″ martensitic transformation:

where ftw and fα″ are volume fraction of {332}〈113〉 twinning and α″ martensite, respectively. ftw and fα″ increase as a function of strain meanwhile consume the volume fraction of the retained β matrix (1 − ftw − fα″). The shear strain of {332}〈113〉 twinning \({\gamma }_{\{332\}\langle 113\rangle }\,=\,\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}}\) and the Taylor factor M = 2.8 representing an average texture orientation in bcc metals. Since a strain-induced ε martensitic embryo in fcc alloys with low stacking-fault energy forms by the stacking of single \(\frac{1}{6}\langle 112\rangle\) partials dissociated from \(\frac{1}{2}\{110\}\langle 111\rangle\) perfect dislocations, it can be considered that the strain accommodated by ε martensite dεε accounts for \(\frac{2}{3}\) of the strain implemented by dislocation glide dεdis being the relation \(d{\varepsilon }_{\varepsilon }\,=\,\frac{2}{3}d{\varepsilon }_{dis}\)38. Given by the shear strain associated with β → α″ transition is one-half of that in a Shockley partial, it suggests that the strain accommodated by α″ martensite accounts for a proportion \(d{\varepsilon }_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }\,=\,\frac{1}{3}d{\varepsilon }_{dis}\). This gives the relation \(d\varepsilon \,=\,(1\,-\,{f}_{tw}\,-\,{f}_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} })d{\varepsilon }_{dis}\,+\,\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}M}d{f}_{tw}\,+\,\frac{1}{3}d{\varepsilon }_{dis}{f}_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }\). Rearranging the expression it derives\(\frac{d{\varepsilon }_{dis}}{d\varepsilon }\,=\,\frac{1}{1\,-\,{f}_{tw}\,-\,\frac{2}{3}{f}_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }}\left(\right.1\,-\,\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}M}\frac{d{f}_{tw}}{d\varepsilon }\left)\right.\). Thereafter the evolution of dislocation density ρ over macroscopic strain ε can be described as:

where \(\frac{d\rho }{d{\varepsilon }_{dis}}\) represents the evolution of dislocation density in the retained β matrix resulting from the competition between dislocation storage \(\frac{d{\rho }^{+}}{d{\varepsilon }_{dis}}\) and annihilation \(\frac{d{\rho }^{-}}{d{\varepsilon }_{dis}}\). The dislocation storage can be significantly promoted by the reduced dislocation mean free path and the interaction with dislocation forest. Thus the storage rate equals:

\(\frac{k}{b}\sqrt{\rho }\) accounts for dislocation self interactions and k is a storage coefficient; b = 2.8 Å the magnitude of the Burgers vector; Λi the dislocation mean free path of each type of obstacle. Deformation twins or martensites can be regarded as thin circular disks according to the stereological relationship39:

where ti the mean width of the respective deformation product; here twin width ttw = 1.2 ± 0.3 μm and α″ martensite width tα″ = 0.3 ± 0.1 μm were adopted14,17. Thereafter the evolution of the dislocation density facilitated by dislocation glide becomes:

The dislocation storage coefficient k = 0.03 ± 0.005 and dynamic recovery coefficient fDRV = 3.0 ± 0.5 were obtained in this work and these values were applied to all tested alloys. The kinetics of martensitic nucleation can be interpreted by a shear-band intersection mechanism24, which is further derived to express the growth of α″ volume fraction as a function of strain: \({f}_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }\,=\,{F}_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }\left\{\right.1\,-\,\exp \left[\right.-{\beta }_{\alpha ^{\prime\prime} }(\varepsilon -{\varepsilon }_{T})\left]\right.{\left\}\right.}^{m}\). Fα″ the saturation α″ volume fraction, m = 0.6 a fixed exponent for the TRIP/TWIP alloys and εT is the critical strain at the onset of α″ formation; βα″ the nucleation kinetics parameter sensitive to alloy composition.

In addition to the enhanced isotropic hardening, a kinematic hardening term produced by dislocation pile-up should be added to the flow stress40. Accounting for the emerging twin interfaces, the backstress can be expressed as \({\sigma }_{b}\,=\,M\mu b\left(\right.\frac{1}{2{t}_{tw}}\frac{{f}_{tw}}{1\,-\,{f}_{tw}}\,+\,\frac{1}{D}\left)\right.n\)6, where n is the number of dislocation loops on a given slip plane. The flux of dislocations arriving at interfaces per slip plane in the retained β matrix is: \(\frac{dn}{d{\varepsilon }_{dis}}\,=\,M\frac{\lambda }{b}\left(\right.1\,-\,\frac{n}{{n}^{* }}\left)\right.\), where λ = 300 nm the mean spacing between slip planes41. n* = 8 ± 2 the saturation number of dislocation pile-up. Analogous to the evolution of dislocation density in Eq. (10), the flux of dislocations over total strain is derived:

In both Eqs. (10) and (14), twinning kinetics dftw/dε is presented, which governs the growing rate of twin volume fraction. It can be obtained by differentiating \({f}_{tw}\,=\,{F}_{tw}\left\{\right.1\,-\,\exp \left[\right.\,-\,{\beta }_{tw}(\varepsilon \,-\,{\varepsilon }_{0})\left]\right.{\left\}\right.}^{m}\) over strain ε, where Ftw is the saturation twin fraction.

The dislocation forest hardening led by the increase in total dislocation density is expressed by the Taylor relation \({\sigma }_{F}=\alpha M\mu b\sqrt{\rho }\), where α ≈ 0.3 reflects the average strength of dislocation interactions. The flow stress is established by incorporating the transition enhanced isotropic hardening and kinematic hardening:

σ0 comprises of the critical resolved shear stress of pure Ti (τCRSS), solid solution hardening (σss) and grain boundary strengthening (σHP):\({\sigma }_{0}\,=\,\left[\right.M{\tau }_{CRSS}\,+\,\left(\right.{\sum }_{i}{B}_{i}^{3/2}{X}_{i}{\left)\right.}^{2/3}\,+\,\frac{{k}_{Y}}{\sqrt{D}}\left]\right.G(T,\dot{\varepsilon })\), where Bi reflects the solid solution hardening coefficient and kY = 0.87 MPa ⋅ m0.5 is adopted as the Hall–Petch coefficient of Ti alloys34. \(G(T,\dot{\varepsilon })\) is a function of temperature and strain rate. The yield stress can be calculated by: \({\sigma }_{Y}\,=\,{\sigma }_{0}\,+\,\alpha M\mu b\sqrt{{\rho }_{0}}\), where ρ0 reflects the stored dislocation density. The validation of the physics-based modelling framework is presented in the “Results” section.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

The codes developed in this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Pollock, T. M. Alloy design for aircraft engines. Nat. Mat. 15, 809–815 (2016).

Peters, M., Kumpfert, J., Ward, C. H. & Leyens, C. Titanium alloys for aerospace applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 5, 419–427 (2003).

Sun, F. et al. Investigation of early stage deformation mechanisms in a metastable β titanium alloy showing combined twinning-induced plasticity and transformation-induced plasticity effects. Acta Mater. 61, 6406–6417 (2013).

Devincre, B., Hoc, T. & Kubin, L. Dislocation mean free paths and strain hardening of crystals. Science 320, 1745–1748 (2008).

Porter, D. A., Easterling, K. E. & Sherif, M. Phase Transformations In Metals And Alloys (Revised Reprint) (CRC press, 2009).

Zhao, G.-H., Xu, X., Dye, D. & Rivera-Díaz-del-Castillo, P. E. J. Microstructural evolution and strain-hardening in TWIP Ti alloys. Acta Mater. 183, 155–164 (2020).

Yasnikov, I. S., Vinogradov, A. & Estrin, Y. Revisiting the considère criterion from the viewpoint of dislocation theory fundamentals. Scr. Mater. 76, 37–40 (2014).

Castany, P., Gloriant, T., Sun, F. & Prima, F. Design of strain-transformable titanium alloys. C. R. Phys. 19, 710–720 (2018).

Hanada, S. & Izumi, O. Correlation of tensile properties, deformation modes, and phase stability in commercial β-phase titanium alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 18, 265–271 (1987).

Morinaga, M. Alloy design based on molecular orbital method. Mater. Trans. https://doi.org/10.2320/matertrans.M2015418 (2016).

Kuroda, D., Niinomi, M., Morinaga, M., Kato, Y. & Yashiro, T. Design and mechanical properties of new β-type titanium alloys for implant materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 243, 244–249 (1998).

Zhao, G.-H. et al. New beta-type Ti-Fe-Sn-Nb alloys with superior mechanical strength. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 705, 348–351 (2017).

Cho, K., Morioka, R., Harjo, S., Kawasaki, T. & Yasuda, H. Y. Study on formation mechanism of {332}〈113〉 deformation twinning in metastable β-type ti alloy focusing on stress-induced α” martensite phase. Scr. Mater. 177, 106–111 (2020).

Min, X., Chen, X., Emura, S. & Tsuchiya, K. Mechanism of twinning-induced plasticity in β-type Ti–15Mo alloy. Scr. Mater. 69, 393–396 (2013).

Ji, X., Emura, S., Min, X. & Tsuchiya, K. Strain-rate effect on work-hardening behavior in β-type Ti-10Mo-1Fe alloy with TWIP effect. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 707, 701–707 (2017).

Lilensten, L. et al. On the heterogeneous nature of deformation in a strain-transformable beta metastable Ti-V-Cr-Al alloy. Acta Mater. 162, 268–276 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. Deformation mechanisms in a metastable beta titanium twinning induced plasticity alloy with high yield strength and high strain hardening rate. Acta Mater. 152, 301–314 (2018).

Brozek, C. et al. A β-titanium alloy with extra high strain-hardening rate: design and mechanical properties. Scr. Mater. 114, 60–64 (2016).

Sun, F. et al. A new titanium alloy with a combination of high strength, high strain hardening and improved ductility. Scr. Mater. 94, 17–20 (2015).

Lee, S. W., Park, C. H., Hong, J.-K. & Yeom, J.-T. Development of sub-grained α+β Ti alloy with high yield strength showing twinning-and transformation-induced plasticity. J. Alloy. Compd. 813, 152102 (2020).

Gordin, D., Sun, F., Laillé, D., Prima, F. & Gloriant, T. How a new strain transformable titanium-based biomedical alloy can be designed for balloon expendable stents. Materialia 10, 100638 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Fabrication and characterization of a novel β metastable Ti-Mo-Zr alloy with large ductility and improved yield strength. Mater. Charact. 139, 421–427 (2018).

Sadeghpour, S. et al. A new multi-element beta titanium alloy with a high yield strength exhibiting transformation and twinning induced plasticity effects. Scr. Mater. 145, 104–108 (2018).

Olson, G. & Cohen, M. Kinetics of strain-induced martensitic nucleation. Metall. Trans. A 6, 791 (1975).

Yang, Y., Chen, H.-L., Chen, Q. & Engström, A. Development of calphad database for both Ti-and TiAl-based alloys. in MATEC Web of Conferences, Vol. 321, 12011 (EDP Sciences, 2020).

Ren, L. et al. Simultaneously enhanced strength and ductility in a metastable β-Ti alloy by stress-induced hierarchical twin structure. Scr. Mater. 184, 6–11 (2020).

Yan, J.-Y. & Olson, G. Computational thermodynamics and kinetics of displacive transformations in titanium-based alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 673, 441–454 (2016).

Green, M. L., Cohen, M. & Olson, G. The pseudoelastic force balance and its application to β-Fe-Be alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. 50, 109–116 (1981).

Zhao, G., Yu, H. & Petrinic, N. Deformation-induced transitions in metals and alloys. Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering (Elsevier, 2021).

Bignon, M., Bertrand, E., Tancret, F. & Rivera-Díaz-del Castillo, P. E. Modelling martensitic transformation in titanium alloys: The influence of temperature and deformation. Materialia 7, 100382 (2019).

Eshelby, J. D. The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 241, 376–396 (1957).

Toda-Caraballo, I., Galindo-Nava, E. I. & Rivera-Díaz-del-Castillo, P. E. J. Understanding the factors influencing yield strength on Mg alloys. Acta Mater. 75, 287–296 (2014).

Galindo-Nava, E. On the prediction of martensite formation in metals. Scr. Mater. 138, 6–11 (2017).

Zhao, G.-H., Liang, X., Kim, B. & Rivera-Díaz-del-Castillo, P. E. J. Modelling strengthening mechanisms in beta-type Ti alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 756, 156–160 (2019).

Mott, P. & Roland, C. Limits to poisson’s ratio in isotropic materials. Phys. Rev. B 80, 132104 (2009).

Yan, J.-Y. & Olson, G. B. Molar volumes of bcc, hcp, and orthorhombic Ti-base solid solutions at room temperature. Calphad 52, 152–158 (2016).

Zhao, G.-H. et al. Alloy design by tailoring phase stability in commercial Ti alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 815, 141229 (2021).

Galindo-Nava, E. I. & Rivera-Díaz-del-Castillo, P. E. J. Understanding martensite and twin formation in austenitic steels: a model describing TRIP and TWIP effects. Acta Mater. 128, 120–134 (2017).

Remy, L. Kinetics of f.c.c. deformation twinning and its relationship to stress-strain behaviour. Acta Metall. 26, 443–451 (1978).

Bouaziz, O., Allain, S. & Scott, C. Effect of grain and twin boundaries on the hardening mechanisms of twinning-induced plasticity steels. Scr. Mater. 58, 484–487 (2008).

Sinclair, C., Poole, W. & Bréchet, Y. A model for the grain size dependent work hardening of copper. Scr. Mater. 55, 739–742 (2006).

Sun, F. et al. Strengthening strategy for a ductile metastable β-titanium alloy using low-temperature aging. Mater. Res. Lett. 5, 547–553 (2017).

Gao, J., Knowles, A. J., Guan, D. & Rainforth, W. M. ω phase strengthened 1.2 GPa metastable β titanium alloy with high ductility. Scr. Mater. 162, 77–81 (2019).

Xu, Y., Gao, J., Huang, Y. & Rainforth, W. M. A low-cost metastable beta Ti alloy with high elastic admissible strain and enhanced ductility for orthopaedic application. J. Alloys Compd. 835, 155391 (2020).

Wang, C., Russell, A. M. & Cao, G. A semi-empirical approach to the prediction of deformation behaviors of β-Ti alloys. Scr. Mater. 158, 62–65 (2019).

Wang, W., Zhang, X., Mei, W. & Sun, J. Role of omega phase evolution in plastic deformation of twinning-induced plasticity β Ti–12V–2Fe–1Al alloy. Mater. Des. 186, 108282 (2020).

Ren, L., Xiao, W., Ma, C., Zheng, R. & Zhou, L. Development of a high strength and high ductility near β-Ti alloy with twinning induced plasticity effect. Scr. Mater. 156, 47–50 (2018).

Fu, Y. et al. Ultrahigh strain hardening in a transformation-induced plasticity and twinning-induced plasticity titanium alloy. Scr. Mater. 187, 285–290 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Hierarchical {332}〈113〉 twinning in a metastable β Ti-alloy showing tolerance to strain localization. Mater. Res. Lett. 8, 247–253 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Strong and ductile beta Ti–18Zr–13Mo alloy with multimodal twinning. Mater. Res. Lett. 7, 251–257 (2019).

Min, X., Tsuzaki, K., Emura, S. & Tsuchiya, K. Enhancement of uniform elongation in high strength Ti–Mo based alloys by combination of deformation modes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 528, 4569–4578 (2011).

Bania, P. J. Beta titanium alloys and their role in the titanium industry. JOM 46, 16–19 (1994).

Chen, N. et al. Reversion martensitic phase transformation induced {332}〈113〉 twinning in metastable β-Ti alloys. Mater. Lett. 272, 127883 (2020).

Boyer, R. & Briggs, R. The use of β titanium alloys in the aerospace industry. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 14, 681–685 (2005).

Cotton, J. D. et al. State of the art in beta titanium alloys for airframe applications. JOM 67, 1281–1303 (2015).

Sadeghpour, S., Abbasi, S., Morakabati, M. & Karjalainen, L. Effect of dislocation channeling and kink band formation on enhanced tensile properties of a new beta ti alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 808, 151741 (2019).

Zhu, W. et al. A novel high-strength β-Ti alloy with hierarchical distribution of α-phase: The superior combination of strength and ductility. Mater. Des. 168, 107640 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Nucleation of stress-induced martensites in a Ti/Mo-based alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 40, 2833–2836 (2005).

Boyer, R. R. Aerospace applications of beta titanium alloys. JOM 46, 20–23 (1994).

Liu, H., Niinomi, M., Nakai, M., Hieda, J. & Cho, K. Changeable young’s modulus with large elongation-to-failure in β-type titanium alloys for spinal fixation applications. Scr. Mater. 82, 29–32 (2014).

Oka, M. & Taniguchi, Y. {332} deformation twins in a Ti-15.5 pct V alloy. Metall. Trans. A. 10, 651–653 (1979).

Wang, W., Wang, X., Mei, W. & Sun, J. Role of grain size in tensile behavior in twinning-induced plasticity β Ti-20V-2Nb-2Zr alloy. Mater. Charact. 120, 263–267 (2016).

Wang, W., Zhang, X. & Sun, J. Phase stability and tensile behavior of metastable β Ti-V-Fe and Ti-V-Fe-Al alloys. Mater. Charact. 142, 398–405 (2018).

Devaraj, A. et al. A low-cost hierarchical nanostructured beta-titanium alloy with high strength. Nat. Commun. 7, 11176 (2016).

Li, C., Chen, J., Wu, X., Wang, W. & Van Der Zwaag, S. Tuning the stress induced martensitic formation in titanium alloys by alloy design. J. Mater. Sci. 47, 4093–4100 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Rolls-Royce plc for their continuing support through the Solid Mechanics University Technology Centre at the University of Oxford. X.Q.L. acknowledges the Swedish Research Council (grant agreement no. 2020-03736). N.P. acknowledges the UK Royal Academy of Engineering for Chair Sponsorship.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H.Z.: conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, modelling, validation and writing—original draft. X.Q.L.: investigation, validation and writing—review and editing. N.P.: supervision, validation, writing—review and editing and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, G., Li, X. & Petrinic, N. Materials information and mechanical response of TRIP/TWIP Ti alloys. npj Comput Mater 7, 91 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00560-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00560-2

This article is cited by

-

A machine learning method to quantitatively predict alpha phase morphology in additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V

npj Computational Materials (2023)