Abstract

The generalized stacking fault energy is a key ingredient to mesoscale models of dislocations. Here we develop an approach to quantify the dependence of generalized stacking fault energies on the degree of chemical disorder in multicomponent alloys. We introduce the notion of a “configurationally-resolved planar fault” (CRPF) energy and extend the cluster expansion method from alloy theory to express the CRPF as a function of chemical occupation variables of sites surrounding the fault. We apply the approach to explore the composition and temperature dependence of the unstable stacking fault energy (USF) in binary Mo–Nb alloys. First-principles calculations are used to parameterize a formation energy and CRPF cluster expansion. Monte Carlo simulations show that the distribution of USF energies is significantly affected by chemical composition and temperature. The formalism is broadly applicable to arbitrary crystal structures and alloy chemistries and will enable the development of rigorous models for deformation mechanisms in high-entropy alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The effect of compositional fluctuations and configurational ordering on the properties of a dislocation is a long-standing problem in materials science1,2,3. Experimental and computational studies of complex-concentrated alloys, also referred to as “high-entropy alloys”4,5,6, have revealed that dislocation motion, core structure, and stacking fault energies can vary significantly with the local ordering of chemical species7,8,9,10,11. Even chemically similar alloys can have drastically different mechanical properties12. Rapid changes in mechanical properties due to minor variations in chemistry undoubtedly have their origin in atomistic deformation mechanisms. Models that are able to link the properties of a dislocation to the degree of long-range and short-range chemical ordering in multicomponent alloys are therefore necessary to provide fundamental insights about the role of chemistry on mechanical properties.

The generalized stacking fault energy (GSF), commonly referred to as the γ-surface, plays an important role in quantifying dislocation properties2,13,14,15. The GSF energy is equal to the work required to displace two halves of a perfect crystal relative to each other along a particular crystallographic plane. It is an essential ingredient in Peirls–Nabarro16,17,18 and phase-field models19,20,21,22 of dislocations, where it is used to assess the energy penalty due to a disregistry between the adjacent crystallographic planes across the slip plane of a dislocation. The GSF energy can also provide qualitative insights about dislocation core structures and preferred partial dislocation structures23.

Here, we develop a method that rigorously captures the dependence of the GSF energy on the degree of ordering in multicomponent alloys. We extend the cluster expansion formalism of alloy theory to describe the energy of displacing and cleaving two halves of a crystal relative to each other as a function of descriptors of the degree of chemical order. We then apply the method to a study of unstable stacking fault (USF) energies in the binary Mo–Nb alloy and use Monte Carlo simulations to quantify the average USF energy as a function of temperature and composition. Our study shows that the GSF energy of the Mo–Nb alloy has both a strong composition and temperature dependence.

Results

Formalism

Two parts of a crystal can be shifted relative to each other by a vector \(\overrightarrow{r}\) that is parallel to a glide plane as shown in Fig. 1a or the crystal can be cleaved by a distance δ perpendicular to the glide plane as in Fig. 1b. The gliding of the two parts of the crystal relative to each other results in a planar fault. The energy per unit area as the two halves of a crystal are shifted relative to each other by \(\overrightarrow{r}\) is conventionally referred to as the GSF energy. It can be defined to be the glide energy either at fixed δ or at a value of δ corresponding to zero tractions perpendicular to the glide plane. Throughout we will use periodic boundary conditions.

The GSF energy of a single component crystal is a periodic function over the space of two-dimensional glide vectors \(\overrightarrow{r}\). Translating the two halves of a crystal by a full lattice vector recovers the unfaulted bulk crystal. Each point in the two-dimensional glide space \(\overrightarrow{r}\) that coincides with a translation vector will therefore have the same GSF energy. Figure 2a shows a (001) glide plane of a body-centered cubic (bcc) crystal. The corresponding two-dimensional glide vector space for the (001) glide plane of bcc is shown in Fig. 2b with glide vectors that recover the bulk bcc crystal shown as squares. Glide vectors that differ from a lattice translation produce a bicrystal with a planar fault. The introduction of a planar fault usually increases the energy of the crystal.

a Schematic figure showing the (001) cut-plane on a conventional bcc crystal. b The two-dimensional glide vector space formed by the relative translations that recover the perfect bulk crystal. The energy of a pure bi-crystal is periodic, with the same energy being recovered at glide vectors shown with squares in the figure.

The GSF energies of multicomponent alloys differ from those of pure elements. The periodicity of the GSF energy that characterize a single component crystal is generally broken in a multicomponent alloy. This is illustrated for a particular ordering of red and green atoms on bcc in Fig. 3a. A glide of the upper half of the crystal relative to the lower half by a [100] translation vector of the underlying bcc crystal structure results in a different ordering of red and green atoms. Though the bcc crystal structure is recovered, a planar defect referred to as an anti-phase boundary has been created. The energy of the crystal before and after the glide by a bcc translation vector is therefore no longer the same since the arrangement of red and green atoms has changed. Two lattice translations along the (001) plane are required for the example of Fig. 3a to recover the original ordering. Figure 3b shows the symmetry in the two-dimensional space of glide vectors \(\overrightarrow{r}\), with blue squares corresponding to the original ordering and yellow squares corresponding to orderings with an anti-phase boundary. For the particular ordering in Fig. 3a, glide vectors along the [010] direction do not change the ordering and the energy remains unchanged.

a Schematic figure showing a periodic ordering on bcc. Upon translating the top and bottom parts of the crystal by a conventional bcc lattice vector (indicated by the thick black arrow), a different local ordering arises in the vicinity of the cut-plane. The planar defect is akin to the well-known “anti-phase” boundaries in metallurgy. b The two-dimensional glide vector space for the ordering shown in a. Squares with the same color correspond to the same ordering and hence the same energy.

The example of Fig. 3a shows that it is necessary to track the degree of order in a multicomponent alloy since glides by a translation vector of the underlying parent crystal structure can change the arrangement of chemical species in the crystal. The state of ordering in a multicomponent solid can be described mathematically by assigning occupation variables to each site of its crystal. Consider a large crystal with N sites (assuming periodic boundary conditions), where each site can be occupied by one of two chemical components A or B. Any ordering of A and B atoms on this crystal can be represented with an occupation vector \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }=\{{\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2},\cdots \ ,{\sigma }_{{\mathrm{N}}}\}\), where σi is an occupation variable that takes the value of +1 if site i is occupied by A and a value of −1 otherwise. The labels i refer to sites in a reference crystal that is not deformed. For the purpose of tracking the configuration of a deformed crystal, we map each site of the deformed crystal onto the nearest site of the reference crystal. A particular configuration of A and B atoms, \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\), for example, may then be converted into a new configuration \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2}\) upon application of a glide that coincides with an elementary translation vector of the underlying parent crystal structure. A second glide by another translation vector may convert \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2}\) into \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3}\). The changes in configuration upon application of glides coinciding with parent crystal translations can be represented in the two-dimensional glide space of \(\overrightarrow{r}\) as schematically illustrated in Fig. 4a. Since the energy of the crystal depends on how the A and B atoms are arranged, it will also vary upon the application of a glide that is equal to a parent crystal translation. This is schematically illustrated in Fig. 4b.

a Schematic two-dimensional glide vector space for a bicrystal, with four different orderings arising at full lattice translations, corresponding to squares. b Schematic energy of a bicrystal being sheared to transform between three orderings labeled σ1, σ2, and σ3. The bulk configurational contribution is labeled Eavg.

While the gliding of two halves of a crystal by a translation vector of the parent crystal changes the configuration of the alloy and therefore its energy, most of the change in ordering is restricted to the vicinity of the glide plane. The local arrangements of A and B atoms far away from the glide plane are unaffected by the glide since those regions have simply been translated rigidly. Chemical interactions in an alloy typically decay over a distance of several nanometers when maintaining the solid in a constant state of strain. The contribution to the energy of the crystal due to a particular arrangement of A and B atoms far away from the glide plane will be identical in two configurations, \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\) and \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2}\), related by a glide since the local degree of ordering at those large distances from the glide plane are identical in both configurations. It is only in regions within the chemical interaction range of the glide plane where the local degree of order is different that an energy difference arises. This motivates the separation of the GSF energy into an average configurational energy and a “configurationally-resolved planar fault energy” (CRPF) that is a local excess energy. The energy, E, of a bi-crystal (shown schematically in Fig. 4b with an initial ordering \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) that is translated by \(\overrightarrow{r}\) and separated by a distance δ can then be written as

In this expression, \({E}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}(\overrightarrow{r}-{\overrightarrow{r}}_{1},\delta ,{\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1})\) is the CRPF energy, with σ1 being one of the three nearest orderings on the perfect crystal for the glide vector \(\overrightarrow{r}\) as schematically illustrated in Fig. 4a. The glide vector \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{1}\) converts \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) to \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\). The average configurational energy, Eavg, is related to the energy of the three nearest configurations as schematically shown in Fig. 4a, and is defined as

where \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1})\), \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2})\) and \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3})\) are the energies of the \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\), \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2}\), and \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3}\) orderings in the perfect crystal. The weights w2 and w3 are related to the glide vectors by:

where \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{12}\) is the glide vector relating configurations \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\) and \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2}\) and \({\overrightarrow{r}}_{13}\) connects \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1}\) to \({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3}\).

Rigorous statistical mechanics calculations of the temperature and composition dependence of the GSF energy require the evaluation of \(E(\overrightarrow{r},\delta ,\overrightarrow{\sigma })\) across all possible decorations of the bi-crystal. This can be computationally intractable when using quantum mechanical techniques. Surrogate models informed from a small set of quantum mechanical calculations that accurately reproduce the bulk and CRPF energies for arbitrary configurations are thus needed to bridge the gap. In the rest of this section, we review the cluster expansion formalism to describe the configurational energy of crystalline solids and subsequently extend it to describe the CRPF energy as a function of configurational ordering.

As shown by Sanchez et al.24, the configurational energy \(E(\overrightarrow{\sigma })\) in a multicomponent solid with a particular crystal structure can be expanded in terms of cluster basis functions according to

where \(E(\overrightarrow{\sigma })\) is the energy of \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\), Vα are expansion coefficients, referred to as effective cluster interactions, and the \({\phi }_{\alpha }(\overrightarrow{\sigma })\) are cluster basis functions. For a binary alloy, the cluster basis functions are defined as

where α refers to a cluster of sites in the crystal, such as pair clusters, triplet clusters etc. The Vα are determined by the chemistry of the alloy. In most alloys, chemical interactions decay beyond a maximum length and cluster size and the cluster expansion of Eq. (4) can be truncated. Clusters related to each other through a symmetry operation in the undecorated crystal have the same expansion coefficient. Strategies that rely on genetic algorithms25, cross-validation26, bayesian regression27, neural networks28, and quadratic programming29 have been succesfully applied to generate high-fidelity cluster expansion models trained to first-principles calculations. The resulting lattice models are typically used in conjunction with statistical mechanics tools such as Monte-Carlo simulations to calculate temperature and composition dependent thermodynamic properties of multi-component solids.

The cluster expansion of Eq. (4) is only valid for a fixed parent crystal structure. In the context of GSF energy surfaces, it can only be used to describe the energy of the bicrystal for glide vectors \(\overrightarrow{r}\) that recover the underlying parent crystal structure. This includes the energies of \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1})\), \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2})\), and \(E({\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3})\) appearing in the expression of average configurational energy Eavg as defined by Eqs. (2), (3), and appearing in Eq. (1). We next extend the cluster expansion approach to describe the CRPF energy of Eq. (1).

We first simplify the problem by exploiting well-established analytical expressions of energy-versus-separation curves to describe the dependence of the CRPF on δ. For most metals, the energy versus separation curve can be accurately represented with the universal binding energy relation (UBER) of Rose et al.30,31 according to

where \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}\) is the CRPF energy at the equilibrium separation δ0, 2κ is the surface energy at infinite separation, and λ is related to the curvature of the energy around the equilibrium separation. The parameters \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}},\,{\delta }_{0},\,\kappa,\) and λ are all functions of the configuration \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) and glide vector \(\overrightarrow{r}\). While Eq. (6) is that for the UBER curve, alternate functional forms such as xUBER32,33 may also be employed.

The dependence of \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}\), κ, δ0, and λ on configuration \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) can be expressed as a cluster expansion. For example, \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}\) can be written as

where the cluster basis functions, ϕα are the same as those defined in Eq. (5), and where Γα are expansion coefficients that are functions of the glide vector, \(\overrightarrow{r}\). Similar to the cluster expansion of Eq. (4), the expansion coefficients in Eq. (7) obey certain symmetry properties dictated by the space group of the undecorated bicrystal having undergone a glide \(\overrightarrow{r}\). Since a glide of a bicrystal by \(\overrightarrow{r}\) in general breaks symmetry, far fewer expansion coefficients will be equivalent by symmetry than for the cluster expansion of the undeformed parent crystal. For example, translation symmetry in directions perpendicular to the glide plane are lost upon application of a glide \(\overrightarrow{r}\). Point clusters that are otherwise equivalent by symmetry in the perfect crystal, are no longer equivalent if they are at different distances from the glide plane. The same holds true for multi-body clusters.

The cluster expansions of the parameters \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}\), κ, δ0, and λ appearing in Eq. (6) extend over all clusters of the bicrystal. However, these cluster expansions should converge rapidly and only clusters within the chemical interaction range from the glide plane are likely necessary in a truncated cluster expansion. This becomes evident when rearranging Eq. (1) to isolate the CRPF energy according to

The above equation shows that the contribution to the energy of the bi-crystal from regions far away from the glide plane is removed when subtracting off the weighted average energy \({E}^{{\rm{avg}}}(\overrightarrow{r},\,{\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{1},\,{\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{2},\,{\overrightarrow{\sigma }}_{3})\), since the configurations σ1, σ2, and σ3 have chemical orderings that are identical (up to a translation vector) to that of the bicrystal beyond the chemical interaction range of the glide plane.

In summary, the parameterization of surrogate models that accurately describe the GSF energies in multicomponent alloys requires two separate cluster expansions. The first is a cluster expansion of the formation energies of orderings over the parent crystal structure. This cluster expansion is required to calculate the average configurational energy, Eavg, in Eq. (1). Methods to parameterize these models are well-established. A second cluster expansion is necessary to describe the short-range CRPF energy. A training dataset can be generated by first calculating the bi-crystal energies, \(E(\overrightarrow{r},\,\delta ,\,\overrightarrow{\sigma })\), for several symmetrically distinct orderings, σ, glide vectors, \(\overrightarrow{r}\), and separation distances, δ. The CRPF energies for each of these configurations can then be calculated with Eq. (8). The resulting CRPF energies for a fixed chemical ordering σ then serve to train the adjustable parameters of Eq. (6), which can then be cluster expanded according to Eq. (7) to describe their dependence on the degree of chemical order. In most Peirls-Nabarro-type models, the bi-crystal is assumed to be under zero stress in the direction perpendicular to the fault. As a result the GSF energy must be minimized relative to the slab separation distance. Thus, the energy given by \({E}_{0}^{{\rm{CRPF}}}\) in Eqs. (6, 7) is the desired quantity when modeling dislocation properties with PN models that assume zero tractions perpendicular to the glide plane.

GSF energies in Mo–Nb

In this section, we illustrate the above cluster expansion formalism by investigating the composition and configuration dependence of USF energies in the binary Mo–Nb alloy. The Mo–Nb alloy adopts the bcc crystal structure at all compositions and forms a disordered solid solution between room temperature and the melt34,35,36. The Mo–Nb binary is of current interest since Mo and Nb are both components of important bcc based high entropy alloys37,38. Studies of the mechanical properties of Mo–Nb alloys indicate that their strength is primarily controlled by the formation and motion of screw dislocations and to some extent edge dislocations39. The screw dislocations are formed along the 〈111〉 direction, and are known to spread on the {110} planes23. Much of the physics of dislocations in Mo–Nb alloys is therefore directly related to the USF energy in the {110} plane for a relative displacement along the 〈111〉 direction. The USF energy serves as a key input to model the motion and evolution of screw dislocations in bcc alloys with phase-field dislocation dynamics40 and classical Peirls–Nabarro type models14,23,41.

The first step in describing the dependence of the GSF energy on ordering is to construct a cluster expansion for the formation energy of the binary bcc Mo–Nb alloy. Figure 5a shows the formation energies of 847 symmetrically-distinct orderings on the bcc crystal structure in the binary Mo–Nb alloy as calculated with density functional theory (DFT). The formation energies are referenced to bcc Mo and Nb at 0 K. More details about the DFT calculations and the cluster expansion that was subsequently trained to these energies can be found in “Methods” section. The convex hull is outlined in black and shows that several ordered phases are predicted to be stable at 0 K. The energies of the 847 orderings as predicted with a cluster expansion are also shown in Fig. 5a as circles. The exceptionally low training error of 0.0008 eV/atom and the excellent qualitative agreement between the ground states as predicted with the cluster expansion and those found with DFT suggest that the configurational energy of the Mo–Nb binary alloy is well-described with a truncated cluster expansion model. Figure 5b also shows the relaxed volume of all orderings relative to that of bcc molybdenum. We find them to vary almost linearly as a function of niobium composition, albeit with a slight negative deviation in close agreement with Vegards law42 (shown schematically by the dashed line in the figure).

The GSF energy surface of a Mo bcc bicrystal for the {110} glide plane along the 〈111〉 direction is shown in Fig. 6a. The introduction of a planar fault due to a glide results in an energy penalty. The fault energy increases until it reaches a maximum at a glide of 1/4〈111〉. This energy corresponds to the USF energy. As the glide vector approaches a full lattice translation in the {110} glide plane (corresponding to 1/2〈111〉) the energy decreases until long-range bcc order is restored, where the energy becomes equal to that of bcc Mo. In calculating the GSF as a function of the glide vector \(\overrightarrow{r}\) of Fig. 6a, we first calculated the energy of the bicrystal as a function of δ along the [110] direction to generate decohesion curves for each value of \(\overrightarrow{r}\). A particular example of such a curve is shown in Fig. 6b. The DFT energies as a function of δ (for fixed \(\overrightarrow{r}\)) were then fit to the UBER30, and the minimum of each curve was used to construct the GSF of Fig. 6a.

a The GSF energy for a bcc Mo bicrystal translated on the (110) plane along the \([1\overline{1}1]\) direction. b The decohesion curves for a pure molybdenum crystal, cleaved along the (110) plane. The energy fit to the UBER is also shown in the dark black line. c The GSF energy for a bcc B2 bicrystal translated on the (110) plane along the \([1\overline{1}1]\) direction. d The unstable stacking fault energies across the composition range, for an undecorated bcc crystal (xNb = 0.1), B2 (xNb = 0.5), and L21 (xNb = 0.25, 0.75) ordering.

A section of the GSF energy for the B2 ordering with a composition of xNb = 0.5 is shown in Fig. 6c. Shifting the two halves of a B2 bicrystal through a full lattice translation results in an anti-phase boundary, which is accompanied by an increase of the energy. Similar to pure molybdenum, an USF is found to exist for a glide corresponding to half a translation vector. Figure 6d collects the calculated USF energies for pure Mo, L21 (Mo3Nb, MoNb3), B2 (MoNb), and pure Nb. We find a strong composition dependence of the USF energies, with the values changing by almost a factor of two with increasing niobium composition. Furthermore, the USF energies vary non-linearly with composition, suggesting that short and long-range order also plays a role in addition to the average concentration. Figure 6d shows the energy at equilibrium separation for the sheared bicrystal.

The CRPF energies of 514 symmetrically distinct USF as calculated with DFT is shown in Fig. 7. The CRPF values vary from ≈0.8 J/m2 for pure niobium to about 2.0 J/m2 in the binary alloy. The spectrum of values at a particular composition is also found to span a large range of values, suggesting that the state of order among Mo and Nb plays a significant role in determining the CRPF energies.

The configurationally-resolved planar fault (CRPF) energy in the Mo–Nb alloy for the {110} plane in bcc with the slabs shifted relative to each other along the 〈111〉 direction. Each point corresponds to a symmetrically distinct configurational ordering in the bi-crystal with a glide vector corresponding to the unstable stacking fault.

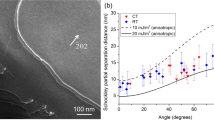

A cluster expansion was parameterized to describe the dependence of the CRPF energies on the degree of Mo–Nb ordering. A comparison of the DFT and cluster expanded CRPF energies is shown in Fig. 8a. Details about the fitting procedure and cluster expansion model are provided in the “Methods” section. The USF energies are reproduced well by the cluster expansion model with a fitting error of 0.016 eV per two-dimensional unit cell of the (110) glide plane. The CRPF energies of configurations that have compositions close to pure molybdenum or niobium have a slightly higher error than configurations with compositions closer to x = 1/2. We validated the model by comparing cluster expansion predictions to DFT values of CRPF energies for 38 stochastically enumerated orderings in a 16 atom supercell. Figure 8b shows a good agreement between the model predictions and the DFT calculations with a validation error of 0.013 eV per unit cell. The interactions within the CRPF cluster expansion are relatively short-range as indicated by the sharply decaying magnitude of the point correlations shown in Fig. 9.

Having fit a cluster expansion that accurately describes the USF energy in the binary Mo–Nb system, we next investigated the composition and temperature dependence of this energy. Grand-canonical Monte-Carlo simulations at temperatures above 600 K are found to be completely disordered at all compositions, in agreement with experiment34. Snapshots of disordered configurations were collected from grand-canonical Monte-Carlo simulations at 600 and 1000 K. Chemical potentials were chosen such that the average composition of niobium was 0.25, 0.5, or 0.75. For each Monte-Carlo snapshot, an USF was introduced in the cell and the USF energy was evaluated with Eq. (1) using the cluster expansions for the CRPF and the formation energy of the bcc Mo–Nb alloy. An USF energy was calculated by introducing a fault in every (110) layer within the simulation cell and for every \(\langle 1\overline{1}1\rangle\) direction within the plane.

Figure 10a shows a histogram of USF energies at three different niobium compositions at a temperature of 1000 K. The USF energies decrease with increasing niobium composition. This is in agreement with the general trend of CRPF energies across compositions in Fig. 7. Our results predict that the stacking fault energies vary strongly with the average composition of the alloy. The spectrum of USF energies at elevated temperatures are normally distributed. The distribution is very sharply peaked at a niobium composition of 0.25 with a slightly more broadened distribution with increasing niobium composition.

a The composition dependence of the unstable stacking fault energies in the binary Mo–Nb alloy at 1000 K. The average unstable stacking fault energies are collected in snapshots from grand-canonical Monte-Carlo calculations at appropriate chemical potentials. b The temperature dependence of the unstable stacking fault energies at 600 and 1000 K at an average simulation cell composition of 0.5.

We investigate the temperature dependence of the USF energies in Fig. 10b. Grand-canonical Monte-Carlo calculations were performed at temperatures of 600 K, and 1000K at chemical potentials that corresponded to average alloy compositions of 0.5. Figure 10b shows that the distribution of USF energies continues to be normally distributed across a wide range of temperatures. The magnitude of the fault energy decreases with increasing temperature. The distribution of energies is also broadened with increasing temperature. These results suggest that the average USF energies vary strongly with niobium composition, while the distribution of energy values is sensitive to the temperature.

Discussion

We have developed a rigorous approach to describe the dependence of generalized stacking fault energies on the degree of ordering in multicomponent alloys. The approach relies on the decomposition of the bicrystal energy into a long-range configurational contribution and a local planar fault energy, referred to as a CRPF. The dependence of the CRPF on configuration is then represented with a short range cluster expansion over sites within a chemical interaction range of the glide plane, while the long-range configurational contribution is captured with the conventional cluster expansion as originally introduced by Sanchez et al.24. The formalism is applied to quantify the USF energy in a prototypical binary Mo–Nb alloy. Monte-Carlo calculations informed by accurate configurational and CRPF cluster expansions predict a strong composition and temperature dependence for the average USF energy.

The tools we have developed here enable rigorous statistical mechanics studies of the effects of short and long-range order on the generalized stacking fault energies in multicomponent alloys. For example, Fig. 11 compares the DFT CRPF energies, the predicted CRPF distributions from Monte-Carlo simulations at 1000 K, and the CRPF energy as a function of composition for a fully disordered random solid solution in the Mo–Nb binary. The spread of the sampled CRPF energies at elevated temperatures in disordered alloys is much smaller than the full range of values that may exist across all symmetrically distinct arrangements of Mo and Nb atoms. For instance, at a composition of xNb = 0.5, CRPF values of distinct binary orderings vary by almost a factor of two between 1–2 J/m2. In contrast, the Monte-Carlo simulations at the same composition predict a distribution that is sharply peaked around 1.4 J/m2, with a spread of only 0.05 J/m2. This suggests that properties of disordered alloys may be difficult to extract directly from the spectrum of calculated CRPF energies without a statistical mechanics treatment.

The figure shows the DFT calculated CRPF energies compared to the energies from a mean-field approximation and the distribution of values from grand-canonical Monte-Carlo simulations at 1000 K. The distributions from Monte-Carlo simulations are shown as violin plots with the breadth of the plot at a given niobium composition corresponding to the relative number of configurations with that CRPF energy.

Figure 11 also shows that the CRPF energies sampled in the Monte Carlo simulations at elevated temperatures and a mean-field estimate are very similar. The mean-field estimate of Fig. 11 was calculated by substituting the correlations of a random alloy in the cluster expansion of the CRPF. The mean-field approximation, therefore, neglects any long-range or short-range order that may exist in the actual alloy and in the Monte Carlo simulations. The fact that the mean-field estimate is very close in magnitude to the Monte-Carlo averages suggests that short-range order does not play a significant role in affecting the USF in the Mo–Nb alloy at 1000 K. The spread of CRPF values, however, varies strongly with niobium composition, suggesting that niobium rich environments have a slightly broader distribution of energies than molybdenum rich environments.

The length-scale over which a dislocation core extends is a key input when modeling dislocation motion and core structure. Dislocations that are spread out over several atomic planes contain large areas with misaligned local neighborhoods, while narrow dislocation cores have only one or two atomic planes that are dis-registered. The length-scale of this misalignment is directly related to the areas that must be used to calculate GSF energies. Within spread out cores, the statistical distribution of GSF energies over large areas is required, while narrow dislocations only require small areas. The GSF energies can be extracted across all length-scales using the techniques described within this study. At the atomistic limit, the CRPF energy (Eq. 8) can be re-written to calculate the energy contribution from a single atomic plane, in a manner similar to the site contribution to the total energy as described by Natarajan and Van der Ven28. Combined with the site energy contributions to the total formation energy, the GSF energy distributions over a single atomic plane can be extracted from Eq. (1). Over larger areas, these site energies must be averaged and the distribution recorded over a “coarse-grained” area, similar to the values shown in Fig. 10. In both scenarios, importance sampling must be used to extract a set of statistically meaningful configurations at the temperature and composition of interest. The effects of long-range and short-range order naturally arise from such a rigorous treatment. Such a dependence of the GSF energy distribution on the area has been recently reported by Zhao et al.43.

The formalism presented in this study brings us closer to a truly rigorous multi-scale model of dislocation motion and evolution in multicomponent alloys. In conjunction with techniques to estimate the effect of configurational disorder on transport coefficients44,45,46, structural phase transitions47, surface and bulk thermodynamics48,49,50, this formalism expands our palette of models to naturally account for the mechanical behavior of engineering materials. Phase-field models of dislocation motion can describe the motion, formation, and structure of dislocations in a variety of crystal structures and material systems. As we move into complex multicomponent alloy chemistries, formalisms that can estimate the GSF energies across vast composition spaces and elevated temperatures are crucial to establishing a rigorous link between electronic structure calculations and phenomenological theories of mechanical properties of materials.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

Total energies of crystals were calculated within the generalized gradient approximation to desity functional theory as parameterized by Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof51 and implemented in the Vienna Ab-Initio Simulation Package52. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method was used to describe the interaction of valence electrons with core states. The PAW potentials treated the semi-core s electrons as valence states. The planewave cutoff was set to 480 eV and an automatic k-point grid with 42 k-points Å−1 were used for Brillouin zone integration. The total energies of configurations in a structure corresponding to the USF along the \([1\overline{1}1]\) direction within the (110) plane was calculated with a static calculation. The separation distance between the two crystal halves was set to 0.15 Å at the pure Mo composition and all lattice parameters were homogeneously scaled based on Vegards law42. The composition dependence of the lattice parameters are informed from the benchmark calculations shown in Fig. 5b. The equilibrium separation δ was found to vary with composition, however a separation scaled by the volume of the crystal relative to that of pure Mo defined as \(\tilde{\delta }\,=\,\delta /{(\frac{V}{{V}_{{\mathrm{Mo}}}})}^{\frac{1}{3}}\) was found to be independent of composition, as shown in Fig. 12. Initial GSF energy calculations were performed with the multishifter code53.

The figure shows the separation distances (δ) at the minimum energy for the unstable stacking fault of the ordered phases in Fig. 6d.

Cluster expansions

Cluster expansion Hamiltonians were parameterized with the clusters approach to statistical mechanics (CASM) software package47,54,55,56. Symmetrically distinct configurations were generated on the parent bcc and USF structure with the CASM software package. All configurations in symmetrically distinct supercells containing up to six atoms were enumerated in bcc. All configurations were enumerated in the primitive structure containing the USF with 8(110) layers. Three hundred and seventy-seven stochastic orderings were also generated in cells containing 16 atoms. Two separate cluster expansions were subsequently trained. Clusters on the bcc crystal structure were chosen from a pool of pairs, triplets, and quadruplets with a maximum length of 10.3, 8.3, 7.3 Å with the genetic algorithm informed with a 10-fold cross-validation score. The resulting RMSE was 0.0008 eV/atom with a cross-validation score of 0.0008 eV/atom. The clusters for the USF energy included pairs and triplets with a maximum length of 7.3 and 5.3 Å. DFT calculations were used to parameterize the cluster expansion Hamiltonian with the L1 regularization to least squares. The regularization parameter was chosen with a 10-fold cross-validation metric.

Monte-Carlo simulations

Grand-canonical Monte-Carlo calculations were performed with a simulation cell containing 16[110] layers and a total of 1600 atoms across a range of chemical potentials and temperatures. Configurational snapshots were extracted from the Monte-Carlo simulations every ten passes after the system was determined to be equilibrated. Within each snapshot, the CRPF was calculated with the CRPF cluster expansion by introducing a planar fault within a (110) layer. The USF energies were recorded for each (110) plane in the simulation cell for a planar fault obtained by translating the two crystal halves along every 〈111〉 direction in the plane. At least 32,000 USF energies were collected for a single composition from the ensemble of configurations generated with Monte-Carlo simulations. The stacking fault energies were subsequently calculated by dividing the activation energy by the area of the (110) plane in a simulation cell with a lattice parameter scaled in accordance with Vegards Law.

Data availability

The data is available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Code availability

The tools to parameterize cluster expansions and perform Grand-Canonical Monte Carlo calculations are available within the CASM software package47,54,55. Structures to calculate the generalized stacking fault energies can be enumerated with the multishifter software package53. Code to evaluate the cluster expanded GSF energies around a slip plane of arbitrary orderings will be shared upon reasonable request.

References

Hull, D. & Bacon, D. J. Introduction to Dislocations. 5th edn (Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann, Amsterdam, 2011).

Bulatov, V. & Cai, W. Computer Simulations of Dislocations, Vol. 3 (Oxford University Press on Demand, Oxford, 2006).

Laughlin, D. E. & Hono, K. (eds.) Physical Metallurgy 5th edn (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2014).

Yeh, J.-W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Cantor, B., Chang, I., Knight, P. & Vincent, A. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. 375-377, 213–218 (2004).

George, E. P., Raabe, D. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 515–534 (2019).

Rao, S., Woodward, C., Parthasarathy, T. & Senkov, O. Atomistic simulations of dislocation behavior in a model FCC multicomponent concentrated solid solution alloy. Acta Mater. 134, 188–194 (2017).

Rao, S. et al. Atomistic simulations of dislocations in a model BCC multicomponent concentrated solid solution alloy. Acta Mater. 125, 311–320 (2017).

Ding, Q. et al. Tuning element distribution, structure and properties by composition in high-entropy alloys. Nature 574, 223–227 (2019).

Ding, J., Yu, Q., Asta, M. & Ritchie, R. O. Tunable stacking fault energies by tailoring local chemical order in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloys. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 8919–8924 (2018).

Li, Q.-J., Sheng, H. & Ma, E. Strengthening in multi-principal element alloys with local-chemical-order roughened dislocation pathways. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–11 (2019).

Miracle, D. B. & Senkov, O. N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 122, 448–511 (2017).

Vítek, V. Intrinsic stacking faults in body-centred cubic crystals. Philos. Mag. 18, 773–786 (1968).

Vitek, V. & Yamaguchi, M. Core structure of nonscrew \(\frac{1}{2}\)(111) dislocations on (110) planes in b.c.c. crystals. ii. peierls stress and the effect of an external shear stress on the cores. J. Phys. F. 3, 537–542 (1973).

Vitek, V. Structure of dislocation cores in metallic materials and its impact on their plastic behaviour. Prog. Mater. Sci. 36, 1–27 (1992).

Peierls, R. The structure of a dislocation. Proc. Phys. Soc. 52, 34–37 (1940).

Nabarro, F. R. N. Dislocations in a simple cubic lattice. Proc. Phys. Soc. 59, 256–272 (1947).

Lu, G., Kioussis, N., Bulatov, V. V. & Kaxiras, E. Generalized-stacking-fault energy surface and dislocation properties of aluminum. Phys. Rev. B 62, 3099–3108 (2000).

Shen, C. & Wang, Y. Phase field model of dislocation networks. Acta Mater. 51, 2595–2610 (2003).

Shen, C. & Wang, Y. Incorporation of γ-surface to phase field model of dislocations: simulating dislocation dissociation in fcc crystals. Acta Mater. 52, 683–691 (2004).

Koslowski, M., Cuitino, A. M. & Ortiz, M. A phase-field theory of dislocation dynamics, strain hardening and hysteresis in ductile single crystals. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 39, 2597–2635 (2002).

Hunter, A., Beyerlein, I. J., Germann, T. C. & Koslowski, M. Influence of the stacking fault energy surface on partial dislocations in fcc metals with a three-dimensional phase field dislocations dynamics model. Phys. Rev. B 84, 144108 (2011).

Vitek, V. & Paidar, V. In: J. P. Hirth (ed) Dislocations in Solids, Vol. 14, 439–514 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2008).

Sanchez, J., Ducastelle, F. & Gratias, D. Generalized cluster description of multicomponent systems. Phys. A 128, 334–350 (1984).

Hart, G. L. W., Blum, V., Walorski, M. J. & Zunger, A. Evolutionary approach for determining first-principles hamiltonians. Nat. Mater. 4, 391–394 (2005).

van de Walle, A. & Ceder, G. Automating first-principles phase diagram calculations. J. Phase Equilib. 23, 348 (2002).

Mueller, T. & Ceder, G. Bayesian approach to cluster expansions. Phys. Rev. B 80, 024103 (2009).

Natarajan, A. R. & Van der Ven, A. Machine-learning the configurational energy of multicomponent crystalline solids. npj Comput. Mater. 4, 1–7 (2018).

Huang, W. et al. Construction of ground-state preserving sparse lattice models for predictive materials simulations. npj Comput. Mater. 3, 1–9 (2017).

Rose, J. H., Ferrante, J. & Smith, J. R. Universal binding energy curves for metals and bimetallic interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 675–678 (1981).

Enrique, R. A. & Van der Ven, A. Decohesion models informed by first-principles calculations: the ab initio tensile test. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 107, 494–508 (2017).

Enrique, R. A. & Van der Ven, A. Solute embrittlement of SiC. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 113504 (2014).

Enrique, R. A. & Van der Ven, A. Traction curves for the decohesion of covalent crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 021910 (2017).

Okamoto, H. Mo-Nb (Molybdenum-Niobium). J. Phase Equilib. 12, 616–617 (1991).

Jiang, C., Wolverton, C., Sofo, J., Chen, L.-Q. & Liu, Z.-K. First-principles study of binary bcc alloys using special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. B 69, 214202–214202 (2004).

Blum, V. & Zunger, A. Prediction of ordered structures in the bcc binary systems of Mo, Nb, Ta, and W from first-principles search of approximately 3,000,000 possible configurations. Phys. Rev. B 72, 020104 (2005).

Senkov, O. N., Miracle, D. B., Chaput, K. J. & Couzinie, J.-P. Development and exploration of refractory high entropy alloys—a review. J. Mater. Res. 33, 3092–3128 (2018).

Senkov, O., Gorsse, S. & Miracle, D. High temperature strength of refractory complex concentrated alloys. Acta Mater. 175, 394–405 (2019).

Maresca, F. & Curtin, W. A. Theory of screw dislocation strengthening in random BCC alloys from dilute to "High-Entropy” alloys. Acta Mater. 182, 144–162 (2020).

Peng, X., Mathew, N., Beyerlein, I. J., Dayal, K. & Hunter, A. A 3D phase field dislocation dynamics model for body-centered cubic crystals. Comput. Mater. Sci. 171, 109217 (2020).

Medvedeva, N. I., Gornostyrev, Y. N. & Freeman, A. J. Electronic origin of solid solution softening in bcc molybdenum alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 136402 (2005).

Vegard, L. Die Konstitution der Mischkristalle und die Raumfullung der Atome. Z. fur Phys. 5, 17–26 (1921).

Zhao, S., Osetsky, Y., Stocks, G. M. & Zhang, Y. Local-environment dependence of stacking fault energies in concentrated solid-solution alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1–7 (2019).

Van der Ven, A., Ceder, G., Asta, M. & Tepesch, P. D. First-principles theory of ionic diffusion with nondilute carriers. Phys. Rev. B 64, 184307 (2001).

Deng, Z., Radhakrishnan, B. & Ong, S. P. Rational composition optimization of the lithium-rich Li 3 OCl 1 – x Br x anti-perovskite superionic conductors. Chem. Mater. 27, 3749–3755 (2015).

Van der Ven, A., Yu, H. C., Ceder, G. & Thornton, K. Vacancy mediated substitutional diffusion in binary crystalline solids. Prog. Mater. Sci. 55, 61–105 (2010).

Thomas, J. C. & Van der Ven, A. Finite-temperature properties of strongly anharmonic and mechanically unstable crystal phases from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 88, 214111–214111 (2013).

Natarajan, A. R., Thomas, J. C., Puchala, B. & Van der Ven, A. Symmetry-adapted order parameters and free energies for solids undergoing order-disorder phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 96, 134204 (2017).

Van der Ven, A. The thermodynamics of decohesion. Acta Mater. 52, 1223–1235 (2004).

Thomas, J. C., Modine, N. A., Millunchick, J. M. & Van der Ven, A. Systematic approach for determination of equilibrium atomic surface structure. Phys. Rev. B 82, 165434 (2010).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Goiri, J. G. & Van Der Ven, A. Multishifter. https://github.com/goirijo/multishifter (2019).

Van der Ven, A., Thomas, J. C., Puchala, B. & Natarajan, A. R. First-principles statistical mechanics of multicomponent crystals. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48, 27–55 (2018).

Puchala, B. & Van Der Ven, A. Thermodynamics of the Zr-O system from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 88, 1–15 (2013).

CASM: a clusters approach to statistical mechanics. https://github.com/prisms-center/Casmcode (2019).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the ONR BRC Program, Grant Number N00014-18-1-2392. Computing resources were provided by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 and the Center for Scientific Computing (CSC) supported by the California NanoSystems Institute and the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC; NSF DMR 1720256) at UC Santa Barbara with funds from the National Science Foundation (CNS-1725797).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.N. and A.V.d.V conceived and designed the project. A.R.N. implemented the formalism, performed the calculations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Natarajan, A.R., Van der Ven, A. Linking electronic structure calculations to generalized stacking fault energies in multicomponent alloys. npj Comput Mater 6, 80 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0348-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0348-z

This article is cited by

-

Ab Initio Investigation of Planar Defects in Immm-Ni2(Cr,Mo,W) Strengthened HAYNES 244 Alloy

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2022)

-

Comparing crystal structures with symmetry and geometry

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Impact of N on the Stacking Fault Energy and Phase Stability of FCC CrMnFeCoNi: An Ab Initio Study

Journal of Phase Equilibria and Diffusion (2021)

-

Cluster Expansion of Alloy Theory: A Review of Historical Development and Modern Innovations

JOM (2021)