Abstract

For the last few years, the research interest in magnetoelectric (ME) effect, which is the cross-coupling between ferroelectric and magnetic ordering in multiferroic materials, has experienced a significant revival. The extensive recent studies are not only conducted towards the design of sensors, actuators, transducers, and memory devices by taking advantage of the cross-control of polarization (or magnetization) by magnetic (or electric) fields, but also aim to create a clearer picture in understanding the sources of ME responses and the novel effects associated with them. Here we derive analytical models allowing to understand the striking and novel dynamics of ME effects in multiferroics and further confirm it with atomistic simulations. Specifically, the role of strain is revealed to lead to the existence of electroacoustic magnons, a new quasiparticle that mixes acoustic and optical phonons with magnons, which results in resonances and thus a dramatic enhancement of magnetoelectric responses. Moreover, a unique aspect of the dynamical quadratic ME response under a magnetic field with varying frequencies, which is the second harmonic generation (SHG), has not been discussed prior to the present work. These SHGs put emphasis on the fact that nonlinearities should be considered while dealing with such systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetoelectric (ME) materials couple electrical and magnetic degrees of freedom. Discovered in 19601,2, researchers’ interest in them faded after a decade due to difficult integration into actual technological devices and lack of microscopic understanding. Yet, a new and vigorous tide of research3,4,5,6 is rising to design sensors, actuators, transducers, and memory devices by taking advantage of the cross-control of polarization (magnetization) by magnetic (electric) fields7,8,9,10. Such tide also aims at creating a deeper understanding of ME effects11,12,13 to properly engineer those aforementioned devices. In particular, dynamical ME effects, which are critical for fast computing operations, have not received the attention they deserve. In this work, an analytical model is derived to shed light on the dynamical strain-induced aspects of the ME effect in multiferroic materials. The model is then verified by first-principles-based simulations within an atomic effective Hamiltonian scheme.

In ME devices, one is often interested in the response of the electric polarization P (or, conversely, the magnetization M) to an applied magnetic field H (or, conversely, an electric field E). For the longest time, the direct control of polarization by magnetic fields, hence the direct coupling of spins with dipole moments, has been the main focus of ME research in single-phase materials. It has however been reckoned that the use of heterostructures and laminar piezoelectric–magnetostrictive composites10,15,16,17 could also lead to control of the polarization, by using strain as a mediator between electric dipoles and spins18,19. Those separate mechanisms lead, in the former case of a “direct” coupling, to the formation of so-called electromagnon quasiparticles12,20,21 (mix of optical phonons and magnons). On the other hand, the latter “indirect” coupling was recently proposed to generate a new quasiparticle, the electroacoustic magnon14, which essentially mixes acoustic and optical phonons with magnons. We note that most studies of the strain-mediated dynamical ME effect focused on (i) the linear ME effect and (ii) heterostructures stacking piezoelectric and ferromagnetic films22,23,24,25. Our work, in comparison, focuses on strain-induced resonances in the dynamical quadratic effect in a single-phase material. This is potentially important as (i) the linear ME effect can vanish or be negligible even in ME materials26 and (ii) working with a single-phase material may lead to easier processing and lower manufacturing costs.

Results and discussion

There are various ways to show that long-wavelength acoustic phonons (i.e., strain) can mediate ME effects. Here we start from a model Hamiltonian that bears resemblance with a Landau expansion of the free energy in terms of powers of the polarization P, magnetization M, and strain η:

with mP and mη representing a mass for the polarization and strain degrees of freedom, whereas k and b are constants. \(\epsilon\) is the coupling constant of the direct bi-quadratic ME effect, Q is an electrostrictive coupling constant, λ is a magnetostrictive coupling constant, and c represents the elastic constant of the system. E represents the external electric field, which we assume to vanish here. We use a kinetic energy that is quadratic in the time derivative of strain, because it mimics what is in the effective Hamiltonian on which our MD equations are based. Such form comes from the integration of Newton’s equations. Deriving the Newtonian dynamical equations for polarization and strain (and including terms of viscosity \(- \gamma _{\mathrm {P}}\dot P\) and \(- \gamma _\eta \dot \eta\)), one gets:

We then use the Fourier transforms \(\tilde P\), \(\tilde \eta\), and \(\tilde M\) of those quantities and obtain an equation for the polarization as a function of magnetization (see Supplementary Information for details):

where we introduced \(\omega _{\mathrm {P}} = \sqrt {\frac{k}{{m_{\mathrm {P}}}}}\), \(\omega _\eta = \sqrt {\frac{c}{{m_\eta }}}\), \(\xi _{\mathrm {P}} = \frac{b}{{m_{\mathrm {P}}}}\), \(\xi _{{\mathrm {PM}}} = \frac{\varepsilon }{{m_{\mathrm {P}}}}\), \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}_{\mathrm {P}} = \frac{{\gamma _{\mathrm {P}}}}{{m_{\mathrm {P}}}}\), \(\tilde Q_{\mathrm {P}} = \frac{Q}{{m_{\mathrm {P}}}}\), \(\tilde Q_\eta = \frac{Q}{{m_\eta }}\), \(\tilde \lambda = \frac{\lambda }{{m_\eta }}\), and \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}_\eta = \frac{{\gamma _\eta }}{{m_\eta }}\).

We now derive Eq. (4) with respect to a magnetic field H(ω0) having angular frequency ω0 and then derive with respect to a second magnetic field \(H\left( {\omega^{\prime}_{0}} \right)\) having another (or the same) angular frequency \(\omega^{\prime}_{0}\), and consequently apply the following small field-limit condition

where \(\beta \left( {\omega^{\prime}_0,\omega _0} \right)\) is the dynamical (general) quadratic magnetic susceptibility. The full expression and the explicit derivations of the quadratic ME constants are detailed in the Supplementary Information. To simplify the analysis, we will consider, as in BiFeO3 (BFO), that the linear ME constant is negligible as compared with quadratic ME terms26. We can then express the dynamical quadratic ME coefficient as

We note that in Eq. 6, the term proportional to ξPM, representing the direct coupling between polarization and magnetization, is exactly the term derived by Laguta et al.27. In a case where the applied field is a combination of an ac field (with frequency ω) superimposed on a dc bias field, the quadratic ME effect will generate periodic changes of the polarization with frequency ω (associated with the case ω0 = ω and \(\omega^{\prime}_{0} = 0\), i.e., a coupling of the ac and dc field) and 2ω (corresponding to the situation \(\omega^{\prime}_{0} = \omega_{0} = \omega\)), which are proportional to the following ME constants

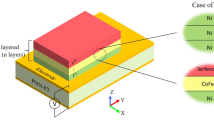

The first component, β(0, ω), is the quadratic ME coefficient, which couples the dc and ac fields, and generates a frequency at ω for the polarization. This component can be considered as an effective linear ME term (as the linear term also generates a signal at the frequency ω) and experiences resonances under the following circumstances, according to Eq. (7): (i) χM(ω) has a resonance, i.e., ω ≈ ωmagnon, (ii) the frequency of the applied field corresponds to an optical phonon frequency (\(\omega = \tilde \omega _{\mathrm {P}}\)), or (iii) the frequency of applied field corresponds to a strain resonance mode (ω = ωη), the latter being shown in Fig. 1a.

Polarization P is usually manipulated by electric fields E. Yet, direct coupling between optical polar phonons and magnetic moments and their quasiparticle-like excitation (called magnon) allows to control polarization with magnetic field H(ω). Such coupled electric and magnetic excitations are called electromagnons. Another pathway to control the polarization with magnetic fields is to use the mediation of acoustic phonon through magnetic moments–strain couplings (magnetostriction and piezomagneticity) and strain–polarization couplings (electrostriction and piezoelectricity). This strain-mediated magnetoelectric coupling involves a combined magnetic, mechanic, and electric excitation called an electroacoustic magnon14. In the case of a, the combined application of a static and dynamical magnetic field with frequency ω, the output change in polarization has frequency ω, and shows strain-induced resonance when the frequency of the dynamical field matches the strain resonance frequency ωη. When a dynamical field H(ω) is applied, a signal at 2ω can also be observed (b) and resonance occurs when the condiction 2ω = ωη is satisfied. At last, in the general case (c), two dynamical fields with frequencies ω0 and \(\omega^ {\prime}_0\) can be concurrently applied to yield a polarization oscillation with frequency \(\omega _0 + \omega ^{\prime}_0\); in this latter case, resonance can be induced when \(\omega _0 + \omega^{\prime}_0 = \omega _\eta\).

The second component, β(ω, ω), is the quadratic ME coefficient that couples the ac field with itself and produces a frequency at 2ω for the polarization (second harmonic generation). This component also experiences resonances under three circumstances, according to Eq. (8): (i) χM(ω) has a resonance, i.e., ω ≈ ωmagnon—exactly as for the first case resonance of β(0, ω); (ii) the frequency of the applied magnetic field corresponds to half of the phonon frequency (\(\omega = \frac{{\tilde \omega _P}}{2}\)); or (iii) the frequency of the applied field is half of the strain frequency (\(\omega = \frac{{\tilde \omega _\eta }}{2}\)).

It is noteworthy that, contrary to the case of β(0, ω) for which the phonon and strain resonances happen at \(\tilde \omega _P\) and \(\tilde \omega _\eta\), in the case of β(ω, ω) the phonon- and strain-related resonances take place at \(\omega = \frac{{\tilde \omega _P}}{2}\) and \(\omega _0 = \frac{{\tilde \omega _\eta }}{2}\), respectively, which is depicted in Fig. 1b for the latter. It is also worth noting that neither β(ω, ω) nor the more general \(\beta \left( {\omega^{\prime}_{0},\omega _0} \right)\) of Eq. (6) were discussed in ref. 14, despite their potential importance for nonlinear physics.

Our focus here is primarily on the quadratic response, β. Note that, due to the combined presence of a DC and an AC magnetic field, the quadratic term β(0, ω) is actually an effective linear ME term from a dynamical perspective (i.e., because of the existence of the dc field which results in the breaking of the magnetic symmetry, we have a ME effect that is linear in the ac field). As shown in the Supplementary Information, we also checked that the linear coefficient, α, does not represent a significant part of the effective linear term β(0, ω).

The terms involving strain-induced resonances are proportional to \(\tilde Q_P\tilde \lambda\) in Eqs. (7) and (8), which we recognize as the product of electro-mechanical and magneto-mechanical couplings. It then becomes clear that the electroacoustic magnon, discussed in ref. 14 (but for which the origin was not clearly explained), is presently revealed as a mixing of long-wavelength acoustic phonons, optical phonons, and magnons, as it results from the combined operation of piezoelectric and magnetostrictive couplings (which we depict in Fig. 1). This new additional handle provides a different path, as depicted in Fig. 1, to enhance the ME effect at variable frequencies as compared with “pure” electromagnons (understood here as resulting from the direct coupling of electrical and magnetic excitations). In practice, one can tailor the mechanical resonance frequency associated with the electroacoustic magnon by adapting the shape of the material, as commonly done in piezoelectric-induced dielectric resonances28.

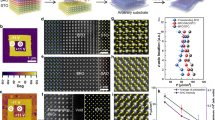

To verify the validity of our model, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using an atomistic effective Hamiltonian (see “Methods” section for details) on a prototypical multiferroic material, i.e., BFO29,30,31,32,33. We neglect the inhomogeneous electric field arising from the time-dependent magnetic field for two main reasons: (1) to avoid the polarization response generated by the dielectric response of BFO to the electric field, i.e., our results truly reflect the ME nature of the response (in other words, we neglect this E-field, as we are solely focusing on the ME response); (2) we use periodic supercells in all three Cartesian directions that practically prevents us from modeling such inhomogeneous electric field. In addition, we assume an arbitrary (large but not infinite) value for the mass of strains and this mass is naturally linked with the frequencies of the electroacoustic magnons. The mass of the strains can be affected by varying the size and shape of the sample to induce a piezoelectric resonance and, therefore, adjust the electroacoustic magnon frequencies. We ran two types of simulations as follows: (1) unclamped simulations for which the homogeneous strain is allowed to change and (2) clamped simulations, with frozen supercell lattice vectors. The temporal behaviors of polarization, magnetization, and the components of strain under the influence of magnetic fields were then studied by Fourier analysis. The results of such analyses are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, when the frequency of the applied ac field is 160 GHz. More precisely, Fig. 2a shows the Fourier transform of the polarization when the system is clamped and unclamped. In both cases, one observes two peaks at 160 GHz and 320 GHz, which are the first and second harmonic responses to the applied magnetic field, respectively, as consistent with the fact that BFO is an ME material. Other peaks also occur, in both of these cases, at 4320 and 7008 GHz, which are optical phonon excitations impacting the polarization evolution. Interestingly, those latter peaks can also be seen in the Fourier transform of magnetization (see Fig. 2b for clamped and unclamped systems) and are thus in fact electromagnons34. Interestingly, when comparing the clamped and unclamped response of the polarization (Fig. 2a), two additional Fourier components can be noticed at 90 and 267 GHz in the second case only. The Fourier analysis also reveals that the peaks at 267 and 90 GHz are respectively associated with the vibrations of diagonal and shear components of homogeneous strain (see Fig. 3). As reckoned in ref. 14, those peaks are thus linked to acoustic phonon excitation (i.e., strain resonances). There is also a peak at 100 GHz in Fig. 3, which is a mode that is observed at any applied frequency of magnetic field and even under no applied magnetic field. It is intrinsic to the strain, but does not couple with magnetization, polarization, and consequently with the ME response, β. The two additional frequencies at 267 and 90 GHz are also present in the Fourier decomposition of the magnetization response in Fig. 2b for the unclamped case, therefore showing that the overall response of the system at this frequency is a mixing of electric, magnetic, and strain response, hence the name electroacoustic magnon given in ref. 14.

Furthermore, Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b show the results of our MD calculations for the value of the first and second components of ME coefficient β(0,ω) and β(ω,ω). In agreement with our aforementioned analytical model, we do observe resonances in β(0,ω) when the strain is unclamped in the simulations and when the frequency of the ac field corresponds to a resonance of the strain (i.e., 90 or 267 GHz). It is noteworthy that the numerically calculated values obtained in our simulations at small frequencies are in agreement with previously reported measurements for β(0,ω)35, which attests of the accuracy of our effective Hamiltonian for BFO.

a Real part of the first and second components of the quadratic magnetoelectric coefficient, β(0,ω) and β(ω,ω), when the homogeneous strain is clamped and unclamped. a Imaginary part of the first and second components of the quadratic magnetoelectric coefficient, β(0,ω) and β(ω,ω), when the homogeneous strain is clamped and unclamped.

Moreover, as it was discussed and predicted earlier in our phenomenological model for the case of β(ω,ω) and as numerically confirmed by Fig. 4 when the strain is unclamped, two strong strain-mediated resonances now take place at 45 and 133 GHz (i.e., precisely half frequencies with respect to the strain-induced resonances of β(0,ω) in he second component of ME response. We also note that resonance frequencies are visible at the strain resonance frequencies of β(0,ω) (i.e., 90 GHz and 267 GHz) in β(ω,ω) too, albeit with smaller intensity. The detailed model in Eq. 40 of the Supplementary Information predicts that such latter resonances must happen in β(ω,ω) and are proportional to the linear ME coupling. It is thus natural to also observe a smaller intensity compared with strain half-frequency resonances in β(ω,ω), as such linear ME coupling is rather weak in BFO26.

Strain-mediated dynamical resonances in both components of the quadratic ME coefficients β(0, ω) and β(ω, ω), which we described at first using a simple analytical model, and then verified using more complex and complete numerical simulations, are thus a promising route to enhance ME couplings. Indeed, as the homogenous strain can vary depending on the size and shape of a sample, the resonances in ME responses can change accordingly36, and thus be tailored to operate at a specific speed. The dependence of the resonance frequencies on strain creates a potential to engineer samples with enhanced ME responses to be used towards fast (by tuning the resonance frequency) and efficient ME devices37. They also give rise to fascinating new physics, as the indirect couplings between strain and electrical and magnetic degrees of freedom allows the emergence of a new type of quasiparticle, i.e., the electroacoustic magnon.

Methods

MD simulations within the framework of an effective Hamiltonian, which was developed for BFO38, were performed to study the quadratic ME coefficient, β, as well as the temporal behavior of electrical polarization and magnetization under the influence of combined dc and ac magnetic fields with various frequencies. The magnetic arrangement considered is G-antiferromagnetic; in other words, we assume the cycloid not to be present, which is the case at large magnetic fields39 or under strain40. A 12 × 12 × 12 supercell with perovskite unit cells (8640 atoms) was subjected to MD simulations with periodic boundary conditions. The degrees of freedom that are considered in the total energy of such effective Hamiltonian scheme include the following: (i) local modes {ui}, which are proportional to dipole moments41; (ii) strain {ηl}, which consists of homogeneous {ηH} and inhomogeneous {ηI} strain tensors; (iii) antiferrodistortive (AFD) motions of oxygen octahedra {ωi}; and (iv) magnetic moments of iron ions {mi}. Here, the subscripts i identify the corresponding unit cells of the supercell. The total energy of this effective Hamiltonian consists of the following: (i) a term EFE({u}, {ηl}), which involves the energy of the local modes and the elastic deformations; (ii) a term EAFD({u}, {ηl}, {ω}), which involves AFD motion and its couplings with local modes and strains; and (iii) a term EMAG({m}, {u}, {ηl}, {ω}), which involves magnetic moments and their couplings with local modes, strains, and AFD motions:

The simulations were performed at the temperature of 1 K to have better statistics. The applied magnetic fields were chosen to be rather large (Hdc = 245 T and hac = 61.2 T), because (i) larger applied fields help observing the ME response, which is known to be small for BFO35,42,43 more accurately in numerical calculations and (ii) in presence of large fields, the quadratic ME response of BFO is much larger than the linear response, making the latter one even more negligible26. It is noteworthy that we also carried out simulations at lower magnetic fields (Hdc = 12.2 T and hac = 3.1 T) or at the temperature of 300 K, which yielded qualitatively similar results14.

Data availability

The authors indicate that the generated and analyzed data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information.

References

Dzyaloshinskii, I. E. On the magneto-electrical effects in antiferromagnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 10, 628–629 (1960).

Astrov, D. N. The magnetoelectric effect in antiferromagnetics. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 708–709 (1960).

Fiebig, M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 38, R123–R152 (2005).

Spaldin, N. A. The renaissance of magnetoelectric multiferroics. Science 309, 391–392 (2005).

Cheng, Y., Peng, B., Hu, Z., Zhou, Z. & Liu, M. Recent development and status of magnetoelectric materials and devices. Phys. Lett. A 382, 3018–3025 (2018).

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Meier, D. & Trassin, M. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16046 (2016).

Eerenstein, W., Mathur, N. D. & Scott, J. F. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 442, 759–765 (2006).

Israel, C., Mathur, N. D. & Scott, J. F. A one-cent room-temperature magnetoelectric sensor. Nat. Mater. 7, 93–94 (2008).

Scott, J. F. Applications of magnetoelectrics. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 4567–4574 (2012).

Ortega, N., Kumar, A., Scott, J. F. & Katiyar, R. S. Multifunctional magnetoelectric materials for device applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 504002 (2015).

Popkov, A. F., Davydova, M. D., Zvezdin, K. A., Solovyov, S. V. & Zvezdin, A. K. Origin of the giant linear magnetoelectric effect in perovskite-like multiferroic BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094435 (2016).

Valdés Aguilar, R. et al. Origin of Electromagnon Excitations in Multiferroic RMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 047203 (2009).

Vaz, C. A. F. et al. Origin of the magnetoelectric coupling effect in Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3/La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 multiferroic heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 127202 (2010).

Sayedaghaee, S. O., Xu, B., Prosandeev, S., Paillard, C. & Bellaiche, L. Novel dynamical magnetoelectric effects in multiferroic BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 097601 (2019).

Popov, C. et al. Direct and converse magnetoelectric effect at resonant frequency in laminar piezoelectric-magnetostrictive composite. J. Electroceramics 20, 53–58 (2008).

Pertsev, N. A., Kohlstedt, A. & Dkhil, B. Strong enhancement of the direct magnetoelectric effect in strained ferroelectric-ferromagnetic thin-film heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 80, 054102, https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.80.054102 (2009).

Janolin, P.-E., Pertsev, N. A., Sichuga, D. & Bellaiche, L. Giant direct magnetoelectric effect in strained multiferroic heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 85, 140401 (2012).

Nan, C.-W. Magnetoelectric effect in composites of piezoelectric and piezomagnetic phases. Phys. Rev. B 50, 6082–6088 (1994).

Laletin, V. M., Filippov, D. A. & Firsova, T. O. The nonlinear resonance magnetoelectric effect in magnetostrictive-piezoelectric structures. Tech. Phys. Lett. 40, 237–240 (2014).

Sushkov, A. B., Aguilar, R. V., Park, S., Cheong, S.-W. & Drew, H. D. Electromagnons in multiferroic YMn2O5 and TbMn2O5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 027202 (2007).

Cazayous, M. et al. Possible observation of cycloidal electromagnons in BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 037601 (2008).

Li, L., Wu, S. Y., Chen, X. M. & Lin, Y. Q. Frequency-dependent magnetoelectric coefficient in a magnetostrictive-piezoelectric composite as a complex quantity. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys 41, 125004 (2008).

Srinivasan, G., Rasmussen, E. T., Gallegos, J., Srinivasan, R., Bokhan, Y. I. & Laletin, W. M. Magnetoelectric bilayer and multilayer structures of magnetostrictive and piezoelectric oxides. Phys. Rev. B 64, 214408 (2001).

Prokhorenko, S., Kohlstedt, H. & Pertsev, N. A. Ferroelectric-ferromagnetic multilayers: a magnetoelectric heterostructure with high output charge signal. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 114107 (2014).

Livesey, K. L. Strain-mediated magnetoelectric coupling in magnetostrictive/piezoelectric heterostructures and resulting high-frequency effects. Phys. Rev. B 83, 224420 (2011).

Kornev, I. A., Lisenkov, S., Haumont, R., Dkhil, B. & Bellaiche, L. Finite-temperature properties of multiferroic BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 227602 (2007).

Laguta, V. V. et al. Room-temperature paramagnetoelectric effect in magnetoelectric multiferroics Pb(Fe1/2Nb1/2)O3 and its solid solution with PbTiO3. J. Mater. Sci. 51, 5330–5342 (2016).

Uchino, K. Ferroelectric Devices (CRC Press, 2009).

Catalan, G. & Scott, J. F. Physics and applications of bismuth ferrite. Adv. Mater. 21, 2463–2485 (2009).

Park, J.-G., Le, M. D., Jeong, J. & Lee, S. Structure and spin dynamics of multiferroic BiFeO3. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 433202 (2014).

Edwards, D. et al. Giant resistive switching in mixed phase BiFeO3 via phase population control. Nanoscale 10, 17629–17637 (2018).

Shanthy, S. & Singh, S. K. Multiferroic BiFeO3 films: candidate for room temperature micro biosensor. Integr. Ferroelectr. 99, 77–85 (2008).

Wang, D., Weerasinghe, J. & Bellaiche, L. Atomistic molecular dynamic simulations of multiferroics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 067203 (2012).

Smolenski, G. A. & Chupis, I. E. Ferroelectromagnets. Sov. Phys. Uspekhi 25, 475–493 (1982).

Tabares-Munoz, C., Rivera, J.-P., Bezinges, A., Monnier, A. & Schmid, H. Measurement of the quadratic magnetoelectric effect on single crystalline BiFeO3. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 24, 1051 (1985).

Sahoo, A. & Bhattacharya, D. Shape-dependent magnetoelectric coupling in nanoscale BiFeO3. J. Alloys Compd 772, 193–198 (2019).

Dutta, M. et al. Magnetoelastoelectric coupling in coreshell nanoparticles enabling directional and mode-selective magnetic control of THz beam propagation. Nanoscale 9, 13052–13059 (2017).

Prosandeev, S., Wang, D., Ren, W., Iñiguez, J. & Bellaiche, L. Novel nanoscale twinned phases in perovskite oxides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 234–240 (2013).

Agbelele, A. et al. Strain and magnetic field induced spin-structure transitions in multiferroic BiFeO 3. Adv. Mater. 29, 1602327 (2017).

Sando, D. et al. Crafting the magnonic and spintronic response of BiFeO3 films by epitaxial strain. Nat. Mater. 12, 641 (2013).

Zhong, W., Vanderbilt, D. & Rabe, K. First-principles theory of ferroelectric phase transitions for perovskites: the case of BiTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 52, 6301–6312 (1995).

Popov, Y. F., Zvezdin, A. K., Vorbev, G. P., Murashev, V. A. & Racov, D. N. Linear magnetoelectric effect and phase transitions in bismuth ferrite. BiFeO3. Jetp Lett. 57, 65–68 (1993).

Lisenkov, S., Kornev, I. A. & Bellaiche, L. Properties of multiferroic BiFeO3 under high magnetic fields from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 79, 012101 (2009).

Acknowledgements

S.O.S., B.X., and L.B. acknowledge the DARPA Grant Number HR0011-15-2-0038 (under the MATRIX program). S.P. acknowledges ONR Grant Number N00014-17-1-2818 and also appreciates support of RFBR 19-52-53030 GFEN. C.P. thanks the ARO grant W911NF-16-1-0227. B.X. also acknowledges the startup fund from Soochow University and the support from Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. We appreciate the support of MRI Grant Number 0722625 from NSF, ONR Grant Number N00014-15-1-2881 (DURIP), as well as a Challenge grant from the Department of Defense, and also acknowledge the High Performance Computing Center at the University of Arkansas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.O.S. performed the numerical calculations. S.P. and B.X. participated in the development of the MD code and running simulations. C.P. conducted the analytical developments. L.B. supervised the study. All authors participated in the analysis of the results and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sayedaghaee, S.O., Paillard, C., Prosandeev, S. et al. Strain-induced resonances in the dynamical quadratic magnetoelectric response of multiferroics. npj Comput Mater 6, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0311-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-0311-z