Abstract

In a spin-driven multiferroic system, the magnetoelectric coupling has the form of effective dynamical Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) interaction. Experimentally, it is confirmed, for instance, for Cu2OSeO3, that the DM interaction has an essential role in the formation of skyrmions, which are topologically protected magnetic structures. Those skyrmions are very robust and can be manipulated through an electric field. The external electric field couples to the spin-driven ferroelectric polarization and the skyrmionic magnetic texture emerged due to the DM interaction. In this work, we demonstrate the effect of optical tweezing. For a particular configuration of the external electric fields it is possible to trap or release the skyrmions in a highly controlled manner. The functionality of the proposed tweezer is visualized by micromagnetic simulations and model analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optimal dynamical control of a particle motion includes several tasks, such as acceleration, braking, and trapping. In the case of nanoparticles, ions, or atoms, the trapping problem becomes more demanding than the others, except trapping of charged particles which is relatively easy with the use of Pauli trap1,2. In the early 90-ties, it was realized that light–atom interaction allows trapping of neutral objects—cesium and sodium atoms in particular3,4. In the case of optical trapping of neutral objects, the light does two jobs: (i) it attracts the particles towards the anti-nodal points of maximum intensity of the optical lattice with the spatial period of the order of optical wavelength, and (ii) the light additionally cools down the atoms. The invention of optical tweezers in 1986 by Arthur Ashkin was a triumph for the manipulation of microparticles with laser light5. Although trapping of various particles is widely discussed in the literature, the problem of trapping of localized excited modes, especially of topological solitons (skyrmions) has not been studied yet.

The concept of skyrmion traces back to the paper of Skyrme6, and to the fundamental paper of Belavin and Polyakov7. It is now well known that skyrmion has a topological character. In particular, invariance of the topological action of the field theory, \({S}_{\mathrm{top}}\left({\bf{n}}\right)=\frac{i\theta }{4\pi }\int\! {\mathrm{d}}{x}_{1}{\mathrm{d}}{x}_{2}{\bf{n}}\cdot \left({\partial }_{1}{\bf{n}}\times {\partial }_{2}{\bf{n}}\right)\), with respect to the infinitesimal transformation \({\bf{n}}\left({\bf{x}}\right)\to {\bf{n}}\left({\bf{x}}\right)+{\epsilon }^{a}\left({\bf{x}}\right){R}^{a}{\bf{n}}\left({\bf{x}}\right)\), (where ϵa is infinitesimal parameter and Ra stands for generators of the O(3) group) defines the specific texture of the vector field \({\bf{n}}\left(x\right)\)8,9,10. The set of different textures of \({\bf{n}}\left(x\right)\), obtained from each other by means of the continuous deformation, has the same invariant topological action and the related conserved topological charge \(W=\frac{1}{i\theta }{S}_{\mathrm{top}}\left({\bf{n}}\right)\). Thus, one could argue that the topological soliton (skyrmion) is a robust object, stable with respect to small perturbations. Apart from this, skyrmions possess dual field-particle properties8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Skyrmions are highly mobile objects. There are several precise recipes on how to drive a skyrmion—either by a spin-polarized electron current or with a magnonic spin current that exerts a magnon pressure on the skyrmion surface. In the recent work41, an alternative mechanism of skyrmion drag was proposed, which is based on a combination of uniform temperature profile and non-uniform electric field. Nevertheless, a vital question that arises is whether the particle nature of skyrmions facilitates their trapping. In what follows, we explore trapping of a skyrmion in the laser field ezEls(x, y, z, t) (with ez being the unit polarization vector of the electric field) and the external electric field E0 = (0, 0, Ez0). There exist several methods to manipulate the polarization of the laser beam. Through these methods, the polarization of the electric field can be switched to the desired direction. For example, one can utilize ultrafast time-dependent polarization rotation in a magnetophotonic crystal42. The colloidal microspheres also can produce dominant Ez component43.

Skyrmions emerge in materials (e.g., in chiral single-phase multiferroics44,45,46) with a sizeable magnetoelectric (ME) coupling term, Eme = −E ⋅ P, where P = cE[(m ⋅ ∇) m − m(∇ ⋅ m)] is the net ferroelectric polarization, with m denoting the unit vector along the magnetization and cE is the magnetoelectric coupling constant. In chiral multiferroics, the coupling of the external electric field with the ferroelectric polarization mimics the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya (DM) term and leads to the noncolinear topological magnetic order. The mechanism of trapping of a skyrmion relies on the interaction between the electric component of the laser field and the ferroelectric polarization of the skyrmion texture. As for the specific materials, we focus on two types of materials: spin-driven single-phase multiferroics and Yttrium Iron Garnet (YIG)11,12,13,14. In particular, we present in addition to YIG, results for the multiferroic material Cu2OSeO3, which supports skyrmions. As detailed below, the emergence of the finite (but small) electric polarization due to non-collinearity of the spin allows for the movement of the skyrmions with external electric fields. YIG and single-phase multiferroic are described by free energies densities:

Here, M = Msm, where Ms is the saturation magnetization, Aex is the exchange stiffness, and Hz is the external magnetic field applied along the z-direction. The free energy of the single-phase multiferroic Cu2OSeO3 has the bulk-related DM interaction term ϵDMI = Dbm ⋅ (∇ × m), where Db is the DMI constant. The effective magnetic field acting on the magnetization follows from the functional derivative of the free energy functional \({\bf{H}}=-\frac{1}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}\frac{\delta {F}_{\mathrm{MF/YIG}}}{\delta {\bf{m}}}\). The interaction energy Eme = −E ⋅ P between the external electric fields E and the spin-driven polarization P enters Eq. (1) as a term, which is linear in P. We note that for spin-driven multiferroics the spin-induced P is quite small (we recall that P = cE[(m ⋅ ∇) m − m (∇ ⋅ m)], where cE is related to the spin–orbit coupling and the spatial variations in m are smooth on an atomic scale). Thus, higher-order terms (P)n and the spatial variations (∇P)n, which both account for the energy density of ferroelectric polarization, are negligible and therefore do not appear in the Eq. (1) above.

The laser manipulated skyrmion dynamics is governed by the stochastic Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) equation47,48, supplemented by the ME term

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio and α is the phenomenological Gilbert damping constant. The effective field Heff for the single-phase multiferroic consists of the exchange field, DM field, and of the applied external magnetic field, \({{\bf{H}}}_{{\rm{eff}}}=\frac{2{A}_{\mathrm{ex}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}{\nabla }^{2}{\bf{m}}-\frac{2{D}_{\mathrm{b}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}\nabla \times {\bf{m}}+{H}_{z}{\bf{z}}\). The temperature in the LLG equation, is introduced through the correlation function of the thermal random magnetic field hl, \(\langle {h}_{l,p}(t,{\bf{r}}){h}_{l,q}(t^{\prime} ,{\bf{r}}^{\prime} )\rangle =\frac{2{k}_{\mathrm{B}}{T}_{\mathrm{sim}}\alpha }{\gamma {\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}V}{\delta }_{\mathrm{pq}}\delta ({\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}^{\prime} )\delta (t-t^{\prime} )\), where p, q = x, y, z, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and V is the volume of the single cell, used in numerical simulations. The value of the temperature Tsim, we determine from the heat equation (see “Methods” section). We note that the physical temperature and the simulation temperature are related through the equation48\({T}_{{\rm{sim}}}=T{a}_{{\rm{sim}}}/{a}_{\mathrm{L}}\), where aL is the lattice constant and asim is the cell length in simulation. Therefore, the physical temperature T = 50 K corresponds to the simulation temperature of \({T}_{{\rm{sim}}}\approx 100\) K.

The z component, Ez0, of the external electric field stabilizes the skyrmion structure. Due to the Gaussian profile of the laser field, Els(x, y, z, t) has the maximum (denoted as E0) in the center of laser spot. The total z component of the electric field, Ez = Ez0 + Els(x, y, z, t), is not homogeneous in the (x, y) plane. Depending on the sign of the oscillating laser field Els(x, y, z, t), the total field Ez can be either negative or positive. We note that for an ultrashort laser pulse, the pulse compressor allows control of the spectral phase \(\phi (\omega ),\,{E}_{\mathrm{ls}}(x,y,z,\omega )=\sqrt{| {E}_{\mathrm{ls}}{| }^{2}}\exp (-i\phi (\omega ))\), where \(\phi (\omega )=-\frac{\omega }{c}n(\omega )d\), n(ω) is the index of refraction and d is the film thickness49. In what follows, we consider both negative E0 < 0 and positive E0 > 0 values of the field. We note that modern laser technologies allow generation of ultrashort single Els(x, y, z, t) = Els(x, y, z)fscp(t) and half cycle Els(x, y, z, t) = Els(x, y, z)fhcp(t) pulses50. The temporal profiles of laser pulses are defined as follows: \({f}_{\mathrm{scp}}(t)=t/{\tau }_{d}\exp (-{t}^{2}/{\tau }_{d}^{2})\), \({f}_{\mathrm{hcp}}(t)=t/{\tau }_{0}\left[\right.\exp (-{t}^{2}/2{\tau }_{0}^{2})-\frac{1}{{b}^{{}^{2}}}\exp (-{t}^{2}/b{\tau }_{0})\left]\right.,\,t>0\). The ultrashort single pulse has both positive and negative Els(x, y, z, t), while the negative field part of fhcp(t) is too small. Therefore, for half-cycle pulse Els(x, y, z, t) can be viewed as positively defined.

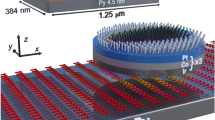

Before presenting the numerical results, we explain the trapping mechanism. The electric field Ez is inhomogeneous only in the x direction. The functional derivative of the ME term with respect to the magnetic moment reads: \(-\frac{1}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}\frac{\delta {E}_{\mathrm{me}}({E}_{z})}{\delta {\bf{m}}}=\frac{{c}_{\mathrm{E}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}[{\partial }_{x}{E}_{z}({m}_{z}{{\bf{e}}}_{x}-{m}_{x}{{\bf{e}}}_{z})+{\sum }_{j}2{E}_{z}(-{\partial }_{j}{m}_{j}{{\bf{e}}}_{z}+{\partial }_{j}{m}_{z}{{\bf{e}}}_{j})].\) Here j = x, y. We focus on the first term fueled by the non-uniform electric field ∂xEz, while the second term corresponds to the effective DM interaction with a strength tunable by a constant electric field41. For tweezing, we suggest using the scanning near-field optical microscopy (SNOM) and advanced nanofabrication procedures. These two methods permit to obtain spots of light 10–20 nm in size; see recent review and references therein51. Contribution of the non-uniform electric field will be presented in the form of inhomogeneous electric torque (IET): \(-\gamma {\bf{m}}\times \left(-\frac{\delta {E}_{\mathrm{me}}({\partial }_{x}{E}_{z})}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}\delta {\bf{m}}}\right)=-\frac{\gamma {c}_{\mathrm{E}}{\partial }_{x}{E}_{z}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}{\bf{m}}\times ({\bf{m}}\times {{\bf{p}}}_{{\bf{E}}}).\) The vector pE = x × ez is set by ez, which points into the direction of electric field. Obviously, the expression of IET is identical to the standard spin transfer torque—cjm × (m × p), because pE in IET mimics the spin polarization direction p. However, while cj depends on the electric current density, the amplitude of the IET depends on the gradient of the electric field ∂xEz and on the ME coupling strength cE. In the case of Gaussian laser beam (for more details, we refer to the Supplementary Note 2), the coefficient in the expression for IET, \(c=\frac{\gamma {c}_{E}{\partial }_{r}{E}_{z}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{s}}\), is determined by the gradient of electric field, while pE = er × z, where \({{\bf{e}}}_{r}=({{\bf{e}}}_{x}x+{{\bf{e}}}_{y}y)/\sqrt{{x}^{2}+{y}^{2}}\) is the unit vector. The underlying mechanism of the skyrmion tweezer is as follows: depending on the direction of the laser field, the IET torque is either centripetal (drives the skyrmion to the center of the beam) or counter-centripetal (drives the skyrmion out of the beam center).

While the energy is supplied through the laser, skyrmion releases energy to the bulk and SNOM shield. Thus, for the comprehensible study of the skyrmion temperature, one needs to solve the heat equation with source and sink terms included. The maximal temperature of the skyrmion texture can be estimated analytically (see “Methods” section). In our case Tmax = 50 K and therefore the skyrmion is stable.

Results and discussion

Skyrmion motion

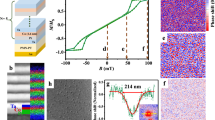

We perform numerical simulations based on Eq. (2) for Néel-type skyrmion in YIG, and Bloch-type skyrmion in Cu2OSeO3 stabilized by the constant electric and magnetic fields. In Fig. 1, we illustrate attraction and repulsion mechanisms of the skyrmion tweezer. In the first case, Fig. 1a, the skyrmion is initially embedded at the point (x, y) = (−7.5, 0) nm, and the laser field is positive, Els(t) > 0. Therefore, pE = −y, c < 0, and the torque winds the skyrmion on clockwise to the laser beam center (0, 0). In the second case, Fig. 1b, the direction of the laser field and IET are reversed, Els(t) < 0, pE = y, c > 0, and the skyrmion winds out anticlockwise from the laser beam center. In Fig. 1c, d, we show the corresponding numerical solutions of the Thiele equation, see Supplementary Note 4.

The simulation has been done the following parameters: Ms = 140 kA m−1, Aex = 3 × 10−12 J m−1, α = 0.001, cE = 0.9 pC m−1, Hz0 = 4 × 105 A m−1, and Ez0 = 1.7 MV cm−1. a The spiral trajectories of the skyrmion winding on clockwise to the laser center. The laser electric field E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1. Initially, the skyrmion center (qx, qy) is embedded in the point (−7.5, 0) nm. b The spiral trajectories of the skyrmion winding off anticlockwise from the laser center. The laser electric field E0 = −1.2 MV cm−1. Initially, the skyrmion center (qx, qy) is embedded in the point (−0.25, 0) nm. Numerical solution based on the Thiele equation is shown in c and d. The spiral trajectories of the skyrmion winding on c and off d the center of the laser beam are for the laser electric field E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1 (c) and E0 = − 1.2 MV cm−1 (d), respectively.

The strategy for skyrmions trapping is as follows: Focus the laser beam on the center of the skyrmion texture. Steer the center of the beam until the electric field is positive Els > 0, the skyrmion follows then the center of the beam (Fig. 2). Rotation of skyrmion leads to a weak oscillation of the skyrmion center (qx(t), qy(t)). When the beam velocity vx is below a critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\), \({v}_{x}<{v}_{x}^{c}=14.22\) m s−1, increase of the beam velocity vx leads to an increase in the velocity of skyrmion drag. When the beam velocity is above \({v}_{x}^{c}\), the skyrmion is not able to follow the center of the laser beam (Fig. 3). The critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\) increases linearly with E0, as is demonstrated in Fig. 4a. Thus, one can argue that the skyrmion behaves as a massive object. Changing sign of the laser field from positive to negative, Els < 0, releases the skyrmion and drives it off the center of the beam (not shown).

Center of the laser beam (x0, y0) is steered with the velocity vx = 1 m s−1 and E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1. The skyrmion center (qx, qy) trapped by the laser beam follows the motion of the center of the laser beam (black and red colors). The inset plot shows the numerical solution of the Thiele equations (Supplementary Note 4). Other parameters as in Fig. 1.

The center of the laser beam is steered with velocity vx = 14.19 (14.22) m s−1 and E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1. For vx = 14.19 m s−1, the skyrmion center (qx(t), qy(t)) follows the center of the laser beam. When, vx = 14.22 m s−1, the skyrmion center is able to follow the laser beam only at the beginning of the evolution, t < 5 ns. Other parameters as in Fig. 1.

a The critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\) as a function of the laser electric field E0. b The critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\) as a function of the frequency fe plotted for electric fields: \({E}_{0}={E}_{l0}+{E}_{l1}\sin (2\pi {f}_{\mathrm{e}}t)\), with El0 = 1.2 MV cm−1 and El1 = 0.07El0. c Dependence of the critical velocity on the El1/El0 at the frequency fe = 0.22 GHz. Other parameters as in Fig. 1.

Skyrmions are topologically protected objects. However, when the ground state is the ferromagnetic state, thermal fluctuations may cause a thermal collapse of the skyrmion. This problem has been widely discussed in the recent literature52,53,54,55. The rate of skyrmion collapse follows the Arrhenius law \(\Gamma ={\Gamma }_{0}\exp \left(-U/T\right)\), where U is the relevant barrier height. In the vicinity of the critical region, the value of the barrier height can be estimated analytically. At a critical value of the magnetic field, \({H}_{\mathrm{c}}\approx J{M}_{0}{\left(D/J\right)}^{4/3}\), the radius of the skyrmion starts shrinking. For Bloch-type of skyrmions, the critical field and height of the barrier can be estimated as follows55\(U/J{M}_{0}^{2}\approx {(D/J)}^{2/3}{\left(1-H/{H}_{\mathrm{c}}\right)}^{3/2}\). The analytical estimation of the barrier is valid only in the critical region. Away from the critical region, the rate of skyrmion collapse can be estimated numerically as56: \(\Gamma =-\langle \frac{1}{{t}_{i}}\mathrm{ln}\,\left(1-\frac{i}{N}\right)\rangle\), where i quantifies the number of collapsed skyrmions at the time ti and N is the total number of skyrmions. Calculations done for T = 50 K, t = 100 ns show that barrier height is U = 386 K and therefore the probability of collapse at T = 50 K is zero. We obtained this information as follows: the time-dependent probability P(t) of skyrmion stability was fitted with the function \(P(t)=\exp (-\Gamma t)\), where Γ is the rate coefficient. The probability P(t) was extracted from the statistics collected through hundreds of repeated simulations. For a given temperature of skyrmion T = 135 K, we simulate the time-dependent probability P(t), as demonstrated in Fig. 5a. Through the fitting of statistical P(t) to the formula \(P(t)=\exp (-\Gamma t)\), we estimate the value of the parameter Γ = 0.012 (ns)−1. In turn, the temperature dependence \(\Gamma (T)={\Gamma }_{0}\exp (-U/T)\) follows Arrhenius law, and through the fitting of curves in Fig. 5c, we obtain U = 386 K, Γ0 = 0.15 (ns)−1. For these parameters, the probability of stability of skyrmion is P = 0.993 at t = 100 ns and T = 50 K, which confirms that the skyrmion is stable (Fig. 5b). This result is supported by the recent experiment57 showing the robustness of skyrmions in Cu2OSeO3.

a For temperature T = 135 K, the time-dependent probability P(t) of skyrmion stability. Through the fitting of function \(P(t)=\exp (-\Gamma t)\) to the probability P(t) extracted from the simulation data (black open squares are extracted from several hundred repeated simulations), we estimate the parameter Γ = 0.012 (ns)−1 (red curve). b Time-dependent probability P(t) for T = 50 K. c Γ as a function of temperature T. Black open squares are obtained through fitting to the simulations statistics. The solid red circles correspond to the function \(\Gamma (T)={\Gamma }_{0}\exp (-U/T)\) for U = 386 K and Γ0 = 0.15 (ns)−1.

We also analyzed the influences of oscillating laser electric field \({E}_{0}={E}_{l0}+{E}_{l1}\sin (2\pi {f}_{\mathrm{e}}t)\). It turns out that the oscillating field drags the skyrmion, and the critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\) as a function of the frequency fe is shown in Fig. 4b. The trapping of the skyrmion depends on the frequency of the field. As we see, the critical velocity \({v}_{x}^{c}\) drops down at fe = 0.2 GHz. Analyzing the spectrum of the skyrmion oscillation frequency (not shown), we find that the frequency fe = 0.22 GHz coincides with the natural frequency of the laser-induced pinning potential of the skyrmion, i.e., the resonant oscillation frequency of the rigid skyrmion. The resonant amplification of the skyrmion oscillations leads to a release of the skyrmion, and thus reduces \({v}_{x}^{c}\). Furthermore, increase of El1 leads to a decrease of \({v}_{x}^{c}\) (Fig. 4c). The large El1 activates nonlinear effects and dependence of the critical velocity on the frequency is not linear anymore, see Fig. 4c for El1 > 0.05El0.

Similar to evanescent Gaussian laser beam, the oscillating laser field also traps the skyrmion. We simulate the laser pulses 70 ps in width and period and steer the center of the laser beam on a distance \(14\sqrt{2}\) nm along y = x in 1.3 ns. As we see in Fig. 6, the skyrmion is trapped by the laser beam and follows the center of the laser beam (Supplementary Note 2). The speed of the skyrmion moving along the y = x axis is about 15.5 m s−1. As we have already mentioned, the obtained results can be also interpreted in terms of the Thiele equation that describes motion of a rigid skyrmion58,59, see Fig. 1c, d and the inset to Fig. 2, as well as the Supplementary Fig. 4.

The skyrmion drag by an oscillating laser pulse. The skyrmion center (qx, qy) follows the center of the laser beam (x0, y0). The laser center (red dots) is steered in \(14\sqrt{2}\) nm in 1.3 ns. For each pulse with whole period 27.3 ns, as demonstrated in inset, E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1 is applied when t < t0 = 1.3 ns and it becomes −0.06 MV cm−1 for t > t0. Right bottom corner: shape of the half cycle laser pulse. Other parameters as in Fig. 1.

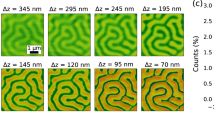

In the single-phase multiferroic Cu2OSeO3 the bulk-type DM interaction11 stabilizes the Bloch skyrmion (its structure is shown in Fig. 7a). The bulk-type DM interaction contributes to the total magnetic field in LLG equation through the effective field \(-\frac{2{D}_{\mathrm{b}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}}\nabla \times {\bf{m}}\). In case of YIG, the role of the bulk-type DM interaction is replaced by the constant electric field Ez0 = 1.7 MV cm−1. In this case, the laser electric field has an amplitude of the order of E0 = 0.2 MV cm−1. As shown in Fig. 7, when the laser center is static, the IET torque induces the centripetal motion of skyrmion. After steering the center of the laser beam, the skyrmion still follows the center of the beam until the critical velocity 13.09 m s−1.

Simulation for Cu2OSeO3 (Ms = 110 kA m−1, Aex = 1 × 10−12 J m−1, α = 0.01, cE = 5.5 pC m−1, Hz0 = 6 × 104 A m−1, Ez0 = 0, and the bulk-type DMI constant Db = 0.15 mJ m−2). a The center of the laser beam (x0, y0) is steered with the velocity vx = 1 m s−1 and E0 = 0.2 MV cm−1. The skyrmion center (qx, qy) trapped by the laser beam follows the motion of the center of the laser beam. The inset plot shows the Bloch skyrmion structure. b The spiral trajectories of the skyrmion winding on clockwise to the laser center. The laser electric field E0 = 0.2 MV cm−1. Initially, the skyrmion center (qx, qy) was at the point (−20, 0) nm. c The center of the laser beam is steered with velocity vx = 13.09 (13.25) m s−1 and E0 = 0.2 MV cm−1. For vx = 13.09 m s−1, the skyrmion center (qx(t), qy(t)) follows the center of the laser beam. When, vx = 13.25 m s−1, the skyrmion center is able to follow the laser beam only at the beginning of the evolution.

Thermal influence of laser radiation

A further influence of the laser pulses is heating. The temperature profile T(x, y, t) induced by the laser heating, through the beam with a moving center, is shown in Fig. 8. The temperature T(x, y, t) is calculated from the heat equation (see “Methods” section). The region of the largest temperature (about 50 K) follows the center of the laser beam and the temperature gradually decreases with the distance from the center. The laser heating leads to the inhomogeneous time-dependent temperature profile and affects the skyrmion dynamics. The main effect of laser-induced heating is that the trapping process becomes non-deterministic. We performed a set of calculations with the same initial conditions and collect ensemble statistics in Fig. 9. The trapping probability P decreases for the higher velocity of the center of beam, but remains finite. Even at the speed vx = 14.32 m s−1 and E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1, P = 54% as is shown in the inset in Fig. 9. An interesting fact is that below the threshold velocity of vx ≤ 14 m s−1 the probability P = 1.

Laser-induced heating temperature profile T(x, y, t) of the Neel skyrmion at a given time t = 11 ns. For solving the heat equation, we implemented a Forward-Time Central-Space (FTCS) scheme63. The velocity of the center of laser beam is vx = 14 m s−1 and the amplitude of the electric field E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1.

The effect of the laser heating on the motion of the Neel skyrmion. The velocity of the center of laser beam is vx = 14.32 m s−1 and the amplitude of the electric field E0 = 1.2 MV cm−1. More than 50 repeated simulations have been performed under the same condition. Inset: dependence of the skyrmion trapping probability P on the velocity of the laser beam vx.

In summary, we have proposed a method of optical control of skyrmions in magnetoelectric materials. Owing to the magnetoelectric coupling, electric field of a laser beam couples to the magnetic moments of the skyrmion. When the field in the laser beam is pre-designed in an appropriate way, one can trap, shift, and then release the skyrmion. Such an optical tweezer may be very useful in control and manipulation of the skyrmion position. Numerical results have been obtained from micromagnetic simulations based on Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation with a contribution from magnetoelectric coupling and additionally from solution of the Thiele equation describing motion of rigid skyrmions. A very good agreement of the results obtained by these two methods has been achieved.

Methods

Micromagnetic modeling

To explore numerically the skyrmion dynamics, we utilize Eq. (2). The simulations have been done for the magnetic film (which is the x − y plane) with the size of 500 nm × 500 nm × 2.5 nm. The film is discretized into the simulation cells of 2.5 nm × 2.5 nm × 2.5 nm (i.e., \({a}_{{\rm{sim}}}=2.5\) nm). The cell size is smaller than the typical exchange length (\(\sqrt{\frac{2{A}_{\mathrm{ex}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}^{2}}}\approx 15\) nm) and the skyrmion size. The LLG equation Eq. (2) is numerically solved through the fifth-order Runge–Kutta scheme with a fixed time step of Δt = 0.1 ps. In the simulation, we first let a single skyrmion to relax to the stationary state and only after apply the laser field. The position of the skyrmion center (qx, qy) is measured through the formulas qx = (∫xqdxdy)/(∫qdxdy) and qy = (∫yqdxdy)/(∫qdxdy) and the simulation data. Here \(q(x,y)=\frac{1}{4\pi }{\bf{m}}\cdot ({\partial }_{x}{\bf{m}}\times {\partial }_{y}{\bf{m}})\) is the topological charge density.

Heat equation

The temperature profile T(x, y, t) is the solution of the heat equation:

Here \(D=\frac{{k}_{\mathrm{ph}}}{\rho C}\) is the thermal diffusivity. In simulation, we considered the parameters: kph = 6 W (m K)−1 is thermal conductivity, ρ = 5170 kg m−3 is the mass density, and C = 570 J (kg K)−1 is the heat capacity. The source term is

where c is the light speed, ϵ0 is the permittivity of vacuum. We exploit axial symmetry and rewrite source in the form \(I={I}_{0}\exp \left(-\frac{{\varrho }^{^{\prime} 2}}{{\sigma }_{0}^{2}}\right)\). The last term bT(x, y, t) has the role of the sink and describes heat exchange of the skyrmion with the rest of the system, i.e., substrate and SNOM shield. Its value can be estimated from the heat diffusivity of the substrate60\(b\approx \frac{3}{\sqrt{\pi }}\frac{{D}_{\mathrm{s}}}{{\sigma }_{0}^{2}}\). In particular, for Ds = 0.24 cm2 s−1, we deduce b = 1.6 × 1010 s−1. The parameter δT = 1.5 × 106 m−1 describes the laser penetration depth and is proportional to the complex part of the refractive index. The absorption efficiency of laser energy lx is equal to the real part of the refractive index. We note that for YIG, both real and complex parts drastically depend on the frequency and magnetic field and, in certain regimes, are rather small61. Thus, parameter lx should be reasonably small. On the other hand, we cannot precisely define the value of lx and consider it as a phenomenological parameter with particular attention to the value lx = 8%. The result for lx = 5%, with a lower temperature T = 30 K, leads to the slightly larger skyrmion trapping probability, see inset in Fig. 9. In simulations, we see that skyrmion temperature linearly increases with lx and for lx = 17%, the temperature is still below T < 100 K. However, the skyrmion temperature depends on the temperature of the substrate and SNOM shield (they play the role of sink). If their temperature is zero, then the maximal temperature of the skyrmion in simulations is below T < 25 K even for lx = 100%.

Exploiting the Green function method, we solve the heat equation analytically62:

The exact analytic solution of Eq. (4) can be obtained for the center of the beam, i.e., the region of the trapped skyrmion.

Here Ei(⋅) is the exponential integral. The analytic solution shows the dependence of the skyrmion temperature on the phenomenological coupling constant b. The maximal temperature of the skyrmion reads Tmax = I0/b. In our calculations, Tmax = 50 K. The temperature in our case conforms to the temperature in the experiment57. The temperature effect can be included in the LLG equation Eq. (1) through the random magnetic field hth, and its correlation function \(\langle {h}_{l,p}(t,{\bf{r}}){h}_{l,q}(t^{\prime} ,{\bf{r}}^{\prime} )\rangle =\frac{2{k}_{\mathrm{B}}{T}_{\mathrm{sim}}\alpha }{\gamma {\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}V}{\delta }_{pq}\delta ({\bf{r}}-{\bf{r}}^{\prime} )\delta (t-t^{\prime} )\). Here, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and V is the volume of the single cell, used in numerical simulations. However one should remember the relation between the physical temperature and the temperature used in the simulations48 \({T}_{{\rm{sim}}}=T{a}_{{\rm{sim}}}/{a}_{\mathrm{L}}\), where aL is the lattice constant and asim is the cell length in simulation, the lattice constant for YIG aL = 12 Å.

In numerical simulation, temperature is calculated from the heat equation Eq. (3) and Forward-Time Central-Space method63. The thermal field in the numerical simulation is determined from \({{\bf{h}}}_{l}={\boldsymbol{\eta }}\sqrt{\frac{2\alpha {k}_{\mathrm{B}}{T}_{{\rm{sim}}}}{{\mu }_{0}{M}_{\mathrm{s}}\gamma V\Delta t}}\), where η is a random vector drawn from a standard normal distribution whose value is changed at every time step, and \(V={a}_{{\rm{sim}}}^{3}\) is the volume of a single finite-difference cell.

Data availability

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sauter, T., Neuhauser, W., Blatt, R. & Toschek, P. E. Observation of quantum jumps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 1696–1698 (1986).

Diedrich, F., Peik, E., Chen, J. M., Quint, W. & Walther, H. Observation of a phase transition of stored laser-cooled ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2931–2934 (1987).

Davis, K. B. et al. Bose-einstein condensation in a gas of sodium atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3969–3973 (1995).

Verkerk, P. et al. Dynamics and spatial order of cold cesium atoms in a periodic optical potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 3861–3864 (1992).

Ashkin, A., Dziedzic, J. M. & Yamane, T. Optical trapping and manipulation of single cells using infrared laser beams. Nature 330, 769–771 (1987).

Skyrme, T. H. R. A non-linear field theory. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 260, 127–138 (1961).

Belavin, A. A. & Polyakov, A. M. Metastable states of two-dimensional isotropic ferromagnets. JETP Lett. 22, 245 (1975).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Dai, Y. Y. et al. Skyrmion ground state and gyration of skyrmions in magnetic nanodisks without the Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054403 (2013).

Kravchuk, V. P. et al. Topologically stable magnetization states on a spherical shell: curvature-stabilized skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 94, 144402 (2016).

Seki, S., Yu, X. Z., Ishiwata, S. & Tokura, Y. Observation of skyrmions in a multiferroic material. Science 336, 198–201 (2012).

Liu, T. & Vignale, G. Electric control of spin currents and spin-wave logic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 247203 (2011).

Stein, J. et al. Control of chiral magnetism through electric fields in multiferroic compounds above the long-range multiferroic transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 177201 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Chiral spin-wave velocities induced by all-garnet interfacial dzyaloshinskii-moriya interaction in ultrathin yttrium iron garnet films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 027203 (2020).

Iwasaki, J., Beekman, A. J. & Nagaosa, N. Theory of magnon-skyrmion scattering in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 89, 064412 (2014).

Ezawa, Z. F. & Hasebe, K. Interlayer exchange interactions, SU(4) soft waves, and skyrmions in bilayer quantum hall ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 65, 075311 (2002).

Lian, Y., Rosch, A. & Goerbig, M. O. Su(4) skyrmions in the ν = ±1 quantum hall state of graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 056806 (2016).

Müller, J. et al. Magnetic skyrmions and skyrmion clusters in the helical phase of Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 137201 (2017).

Liu, Y.-H., Li, Y.-Q. & Han, J. H. Skyrmion dynamics in multiferroic insulators. Phys. Rev. B 87, 100402(R) (2013).

Wilson, M. N., Butenko, A. B., Bogdanov, A. N. & Monchesky, T. L. Chiral skyrmions in cubic helimagnet films: the role of uniaxial anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 89, 094411 (2014).

Schütte, C. & Garst, M. Magnon-skyrmion scattering in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 90, 094423 (2014).

White, J. S. et al. Electric-field-induced skyrmion distortion and giant lattice rotation in the magnetoelectric insulator Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 107203 (2014).

Lin, S.-Z. & Bulaevskii, L. N. Quantum motion and level quantization of a skyrmion in a pinning potential in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 88, 060404(R) (2013).

Wang, C., Gong, M., Han, Y., Guo, G. & He, L. Exotic spin phases in two-dimensional spin-orbit coupled models: importance of quantum effects. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115119 (2017).

Kong, L. & Zang, J. Dynamics of an insulating skyrmion under a temperature gradient. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 067203 (2013).

Derras-Chouk, A., Chudnovsky, E. M. & Garanin, D. A. Quantum collapse of a magnetic skyrmion. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024423 (2018).

Haldar, S., von Malottki, S., Meyer, S., Bessarab, P. F. & Heinze, S. First-principles prediction of sub-10-nm skyrmions in Pd/Fe bilayers on rh(111). Phys. Rev. B 98, 060413(R) (2018).

Leonov, A. O. & Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 6, 8275 (2015).

Psaroudaki, C. & Loss, D. Skyrmions driven by intrinsic magnons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 237203 (2018).

Psaroudaki, C., Hoffman, S., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Quantum dynamics of skyrmions in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041045 (2017).

Langner, M. C. et al. Coupled skyrmion sublattices in Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 167202 (2014).

Leonov, A. O. et al. The properties of isolated chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films. New J. Phys. 18, 065003 (2016).

Lin, S.-Z., Batista, C. D., Reichhardt, C. & Saxena, A. AC current generation in chiral magnetic insulators and skyrmion motion induced by the spin seebeck effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 187203 (2014).

Sun, F., Ye, J. & Liu, W.-M. Quantum incommensurate skyrmion crystals and commensurate to in-commensurate transitions in cold atoms and materials with spin–orbit couplings in a Zeeman field. New J. Phys. 19, 083015 (2017).

Leonov, A. O. & Mostovoy, M. Edge states and skyrmion dynamics in nanostripes of frustrated magnets. Nat. Commun. 8, 14394 (2017).

Murooka, R., Leonov, A. O., Inoue, K. & Ohe, J.-i Current-induced shuttlecock-like movement of non-axisymmetric chiral skyrmions. Sci. Rep. 10, 396 (2020).

van Hoogdalem, K. A., Tserkovnyak, Y. & Loss, D. Magnetic texture-induced thermal hall effects. Phys. Rev. B 87, 024402 (2013).

Komineas, S. & Papanicolaou, N. Skyrmion dynamics in chiral ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064412 (2015).

Lin, S.-Z., Reichhardt, C., Batista, C. D. & Saxena, A. Particle model for skyrmions in metallic chiral magnets: dynamics, pinning, and creep. Phys. Rev. B 87, 214419 (2013).

Müller, J. & Rosch, A. Capturing of a magnetic skyrmion with a hole. Phys. Rev. B 91, 054410 (2015).

Wang, X.-g, Chotorlishvili, L., Guo, G.-h, Jia, C.-L. & Berakdar, J. Thermally assisted skyrmion drag in a nonuniform electric field. Phys. Rev. B 99, 064426 (2019).

Musorin, A. I., Sharipova, M. I., Dolgova, T. V., Inoue, M. & Fedyanin, A. A. Ultrafast faraday rotation of slow light. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 024012 (2016).

Kofler, J. & Arnold, N. Axially symmetric focusing as a cuspoid diffraction catastrophe: scalar and vector cases and comparison with the theory of mie. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235401 (2006).

Cheong, S.-W. & Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13–20 (2007).

Katsura, H., Nagaosa, N. & Balatsky, A. V. Spin current and magnetoelectric effect in noncollinear magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 057205 (2005).

Mostovoy, M. Ferroelectricity in spiral magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 067601 (2006).

García-Palacios, J. L. & Lázaro, F. J. Langevin-dynamics study of the dynamical properties of small magnetic particles. Phys. Rev. B 58, 14937–14958 (1998).

Hahn, M. B. Temperature in micromagnetism: cell size and scaling effects of the stochastic Landau–Lifshitz equation. J. Phys. Commun. 3, 075009 (2019).

Diels, J. C. In Dye Laser Principles (eds Duarte, F. J. & Hillman, L. W.) ch. 3 (Academic, New York, 1990).

Moskalenko, A. S., Zhu, Z.-G. & Berakdar, J. Charge and spin dynamics driven by ultrashort extreme broadband pulses: a theory perspective. Phys. Rep. 672, 1–82 (2017).

Bazylewski, P., Ezugwu, S. & Fanchini, G. A review of three-dimensional scanning near-field optical microscopy (3d-snom) and its applications in nanoscale light management. Appl. Sci. 7, 973 (2017).

Müller, G. P. et al. Duplication, collapse, and escape of magnetic skyrmions revealed using a systematic saddle point search method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 197202 (2018).

Desplat, L., Suess, D., Kim, J.-V. & Stamps, R. L. Thermal stability of metastable magnetic skyrmions: entropic narrowing and significance of internal eigenmodes. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134407 (2018).

Rohart, S., Miltat, J. & Thiaville, A. Path to collapse for an isolated Néel skyrmion. Phys. Rev. B 93, 214412 (2016).

Derras-Chouk, A., Chudnovsky, E. M. & Garanin, D. A. Thermal collapse of a skyrmion. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 083901 (2019).

Garanin, D. A. Uniform and nonuniform thermal switching of magnetic particles. Phys. Rev. B 98, 144425 (2018).

Wilson, M. N. et al. Measuring the formation energy barrier of skyrmions in zinc-substituted Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. B 99, 174421 (2019).

Zhang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ezawa, M. Magnetic bilayer-skyrmions without skyrmion hall effect. Nat. Commun. 7, 10293 (2016).

Tomasello, R. et al. A strategy for the design of skyrmion racetrack memories. Sci. Rep. 4, 6784 (2014).

Bäuerle, D. Laser Processing and Chemistry (Springer, 2011).

Kuznetsov, E. A., Rinkevich, A. B. & Perov, D. V. Resonance variations of the microwave refractive index in yig plates. Tech. Phys. 64, 629–634 (2019).

Tikhonov, A. N. & Samarskii, A. A. Equations of Mathematical Physics (Dover Publications, 1990).

Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T. & Flannery, B. P. Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing 3rd edn. (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Albert Fert and Vladimir Chukharev for numerous discussions and suggestions. This work was supported by the National Science Center in Poland as a research Project No. DEC-2017/27/B/ST3/02881, by the DFG through the SFB 762 and SFB-TRR227, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 11704415,024410-7 and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China No. 2018JJ3629. A.E. acknowledges financial support from DFG through priority program SPP1666 (Topological Insulators), SFB-TRR227, and OeAD Grants Nos. HR 07/2018 and PL 03/2018. This work was supported by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (SRNSFG) [Grant No. FR-19-4049]. Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.K.D., J.B., L.C. and A.E. conceived the idea and designed this research project. Calculations were performed by X.-G.W., N.A. and C.J. Figures were produced by X.-G.W. and I.V.M. All authors contributed to the discussion and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, XG., Chotorlishvili, L., Dugaev, V.K. et al. The optical tweezer of skyrmions. npj Comput Mater 6, 140 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00402-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00402-7

This article is cited by

-

Optical skyrmions and other topological quasiparticles of light

Nature Photonics (2024)