Abstract

A theory of the time-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TRPES) is developed, which enables to explore the real-time electron dynamics of infinitely periodic crystalline solids. In the strongly correlated electron systems NiO and CuO, the early-stage dynamics of the valence band edge are found to be sharply contrasted between those in the spectra of TRPES. This provides a new dynamical insight to the Zaanen–Sawatzky–Allen (ZSA) classification scheme of correlated insulators and makes us assert that NiO dynamically behaves like the Mott–Hubbard insulator (MHI) and CuO like the charge transfer insulator (CTI). In the two-dimensional carbon layer graphene, the real-time electron dynamics of quantum-phase-dressed excited states, i.e., due to the Berry phase and the pseudospin correlation, are investigated in an unprecedented way through the time-resolved angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TR-ARPES). In particular, the dephasing dynamics of optically doped electrons and holes in the massless Dirac band, accompanying a field-induced gliding of the Dirac cone, are discovered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrafast phenomena of the optically driven transient changes in charge, spin, lattice, and orbital degrees of freedom and their crosslinks provide benchmarks for the photoinduced dynamics of a given material. In particular, the dynamical instabilities induced by the cooperative interplays among those degrees of freedom would be classified as the photoinduced phase transitions (PIPTs)1,2, which are in fact observed in a wide range of materials. An optical doping through the pulse laser pumping triggers the photoinduced deployments of simultaneously introduced electrons and holes differently from the chemical doping, which carries all the essence of the photoinduced dynamics and related PIPTs. Hence, instead of conventional approaches based on the time-resolved macroscopic electro-optic measurements3,4,5, one may attempt to explore the photoinduced ultrafast dynamics through an explicit tracking of the creation, development, and destruction of optically doped electrons and holes. For the purpose, the most promising framework would be the time-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (TRPES). TRPES, a kind of the pump–probe spectroscopy, takes a snap shot of the photoemission using the delayed probe pulse under the dynamics initiated by the pump pulse and monitors the time evolution in the electronic structures of a material out of equilibrium in a manifold of energy and time6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, i.e., conjugate variables in the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

Insulator–metal transition (IMT) is one of the most exciting phenomena in condensed matter physics17. One of the possible routes to drive IMT is to simultaneously introduce electrons and holes by irradiating an insulator, i.e., the photoinduced IMT (PIIMT)1,2. It is TRPES that is a powerful tool to probe PIIMT in a real-time domain through a direct observation of temporal changes of the electronic structure caused by optically doped electrons and holes6,7,8,9,10,11,13,16,18,19. In the experimental aspect, TRPES requires high standards of quantum optics and electronics so that it has only recently been implemented actively. Meanwhile, in the theoretical side, TRPES has been less explored due to inherent difficulties in describing the real-time dynamics. Although the nonequilibrium Green’s function method was proposed, an actual treatment of the method has been still in a sort of model calculation20,21,22. Instead, for a theoretical description of TRPES for real solids (i.e., infinitely periodic solids beyond the model consideration), we attempt to reformulate the theory of TRPES based on the many-body time-dependent Schrödinger equation23 such that the first-principles calculation can be applied. In fact, no established theoretical formulation is available yet especially for infinitely periodic crystalline solids in the first-principles framework24,25. For the numerical encoding of TRPES, a complicated engagement of many electrons system in the photoemission process should be managed at an appropriate level of approximation.

We develop an original theory of TRPES within the three-step model of photoemission and address optically induced transient changes in the electronic structure of transition metal oxides NiO and CuO in the angle-integrated mode and two-dimensional gapless semiconductor graphene in the angle-resolved mode. First, we choose NiO and CuO due to the following reasons. (i) Although NiO and CuO are strongly correlated electron systems, the modified Becke–Johnson local density approximation (mBJ-LDA)26 potential is found to describe their ground states quite successfully. This gives a possibility to manage the electron dynamics of the two materials in a new formalism of TRPES with time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) based on mBJ-LDA. (2) NiO and CuO have been studied for a long time as typical transition metal oxides but rarely in respects of the real-time electron dynamics. Hence, critical scientific insights may be expected in their real-time electron dynamics. Next, we choose graphene because it may be a very good test bed for a new formulation of TRPES based on the first-principles calculation and also a very interesting system especially in the dynamic respects. Now we examine the time evolution of the valence band edges of NiO and CuO and provide a new dynamical vision to the Zaanen–Sawatzky–Allen (ZSA) scheme27. It is found that a strong optical pump results in a reconstruction of valence band edge to create incoherent in-gap states in NiO, whereas a simple weight reduction in the valence band edge of CuO. With this finding, we conclude that the dynamical response of NiO is like the Mott–Hubbard insulator (MHI) and that of CuO like the charge transfer insulator (CTI). For a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice of carbon atoms graphene, we investigate the dynamics of k-dependent excited states, which are dressed with the dynamical quantum phase determined by the Berry phase and the pseudospin correlation depending on the polarizations of pump and probe pulses. Those excited states in the massless Dirac band, incorporating a gliding of the Dirac cone according to an acceleration of electrons along the easy direction, are further explored by tracing optically doped electrons and holes in the real-time domain.

Results

Theoretical formulation of TRPES

In the present formulation, TRPES is formally based on the three-step model of the photoemission: the photoelectron (i) creation, (ii) propagation and penetration through the surface, and (iii) escape to the vacuum, and additionally the free electron approximation for the final state28. Inspired from the first-order time-dependent perturbation theory, we propose the photoemission amplitude

To build up a theoretical formulation of TRPES from Eq. (1), we employ the first-principles TDDFT calculation implemented in ELK (see http://elk.sourceforge.net). We obtain the time-evolving Kohn–Sham (KS) wave function |n, q;τ〉 from the time-dependent KS equation for the occupied electron with the momentum q and the band index n, whose time evolution is governed entirely by an optical pump Apump(τ) through TDDFT. |k(τ)〉 is a time-evolved final state of a plane wave to be overlapped with |n, q;τ〉 through p, where p is the linear momentum operator. The equation provides a powerful chance for directly calculating TRPES within the sudden approximation even though the KS wave function is in an infinitely periodic atomic system. Now \(c_{\mathbf{k}}^{n,{\mathbf{q}}}(\tau _{\rm{d}})\) stands for a probability amplitude for finding the photoelectron from |n, q;τ〉, which can then be computed through the first-order time-dependent perturbation theory due to the probe pulse Aprobe(τ − τd), i.e., extreme ultraviolet pulse, with the time delay τd with respect to the pump pulse Apump(τ),

In Eq. (2), we simply write |k(τ)〉 as \(\left| {\mathbf{k}} \right\rangle {\mathrm{e}}^{ - {\mathrm{i}}{\int} {\rm{d}} {\uptau}\left( {\frac{{{\mathbf{k}}^2}}{2} + E_{\mathrm{F}}} \right)}\) and insert a completeness identity for the ground KS states. This increases an efficiency for calculating spectra of TRPES since only the time-dependent momentum matrices 〈n′, q|p|n, q;τ′〉 are required for the calculation process, that is, |n, q;τ′〉 does not have to be expanded into |k(τ) basis for every time step. Vector potentials of pump and probe pulses are given by \({\mathbf{A}}_{{\mathrm{pump}}}\left( \tau \right) = {\mathbf{A}}_{{\mathrm{pump}}}^0{\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega _{{\mathrm{pump}}}} \right)\) and \({\mathbf{A}}_{{\mathrm{probe}}}\left( \tau \right) = {\mathbf{A}}_{{\mathrm{probe}}}^0{\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega _{{\mathrm{probe}}}} \right)\), respectively, with \({\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega } \right) = \cos \left( {\omega \tau } \right)\cos ^2(\pi \tau {\mathrm{/}}2\bar \tau ){\mathrm{{\Theta} }}(\bar \tau - |\tau |)\). Here Θ(x) is the Heaviside step function and \(\bar \tau\) is adopted as 4.9 fs for the pump pulse and 2.4 fs for the probe pulse. Each pulse has then the duration of 2\(\bar \tau\). Furthermore, \(A_{{\mathrm{probe}}}^0A_{{\mathrm{pump}}}^0{\mathrm{}}^{ - 1} \ll 1\) is assumed. Hence, the spectrum of TRPES gets to be \(J_{\mathbf{k}}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right) = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n,{\mathbf{q}}} {\left| {c_{\mathbf{k}}^{n,{\mathbf{q}}}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right)} \right|^2}\). By using Eq. (2), we demonstrate photon-dressed Floquet states of Ar atomic orbitals in Supplementary Fig. 1, which guarantees that Eq. (2) can provide proper spectra of nonequilibrium states. Based on the method, in the present study, we mainly concentrate on the angle-integrated spectra of TRPES for the strongly correlated systems NiO and CuO, whereas on the angle-resolved spectra of TRPES by keeping the wave vectors k for the two-dimensional semiconductor graphene. In our approach of the three-step model, step (ii) is actually ignored by neglecting the surface scattering, which confirms that the TDDFT calculation, i.e., the time evolution of |n, q;τ〉, could be carried out with the full translational symmetry of the material. It is noted that the formulation of Eqs. (1) and (2) does not include the higher-order electron emission process, such as the Auger process.

Correlation induced band mixing in the excited states of NiO and CuO

Over the past few decades, one of the most intensively discussed issues at the heart of condensed matter physics is the strongly correlated electron system. Historically, the fundamental test bed of correlated solid electrons has been the 3d transition metal oxide, which includes NiO that has then been long considered to be MHI. In MHI, a band gap opened between the upper Hubbard band (UHB) and the lower Hubbard band (LHB) is scaled by the d–d Coulomb correlation U29, which is described by the Hubbard model30. Later, however, the X-ray photoemission spectroscopy31,32 and the cluster calculation33 of NiO have suggested that, differently from the previous understanding, ligand p orbitals from oxygen atoms are strongly associated with the valence edge and the band gap is determined between the p-like ligand band and the d-like UHB. This indicates another kind of insulator, CTI, according to the ZSA scheme27, which classifies transition metal oxides into MHI and CTI according to a characteristic of the valence band edge, i.e., whether the valence band edge is made of d or p orbital. Later, there have followed more investigations that NiO should be possibly classified as an intermediate one rather than either MHI or CTI because the p–d hybridization nontrivially affects the electronic structure34,35,36. One may expect better understanding of the insulating nature of NiO and solve the aforementioned long-time controversy through a different angle of view, for instance, the real-time response of the electronic structure. Unlike NiO, CuO has been regarded as CTI due to a relatively simple electronic structure with the Coulomb correlation U larger than the charge transfer strength37. Here we demonstrate photoinduced electron dynamics of NiO and CuO through an angle integrated mode of TRPES, i.e., \(J_{\left| {\mathbf{k}} \right|}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right) = {\int} {\rm{d}} {\mathrm{{\Omega} }}_{\mathbf{k}}\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n,{\mathbf{q}}} {\left| {c_{\mathbf{k}}^{n,{\mathbf{q}}}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right)} \right|^2}\). Moreover, for the calculation, we adopt the Tran–Blaha modified Becke–Johnson potential and the Perdew–Wang LDA (TB-mBJLDA) as the exchange and the correlation potential26. TB-mBJLDA is shown to predict correctly band gaps and magnetic moments for NiO and CuO, whose reliability would be of the same order as the hybrid functionals or the GW method (Supplementary Table 1).

Density of states (DOS) of NiO and CuO are displayed in Fig. 1a, b. Comparing between those, p- and d-band characters are mixed at the valence band edges of both materials, but the p character is found relatively stronger in CuO than in NiO. \(E_{\rm{pump}}^{0} = \omega _{\rm{pump}}A_{\rm{pump}}^{0} = 1\,{\rm{V}}\AA^{- 1}\) is taken, where ωpump is chosen resonant to a band gap of the material. ωprobe is taken as 25 eV. In Fig. 1c, d, we provide the spectra of TRPES at time delays τd = −9.8 and 13.4 fs for NiO and CuO, respectively. τd is the delay time between the two pulses. Let us be aware that spectra at τd = −9.8 fs (i.e., before the pump pulse arrives) corresponds to the conventional PES, which directly reflect the occupied DOS in the ground state. However, spectra at τd = 13.4 fs are indeed interesting in that snapshots of dynamical responses of the electronic structure under the optical pumping are taken. It is of great importance to note that both valence and conduction band edges are reconstructed to shift inwardly so that in-gap states are created in NiO of Fig. 1c. The resultant gap is found much smaller than the original gap \(E_{\rm{g}}^0\). In CuO of Fig. 1d, however, such a shift of the valence band edge is not shown. Instead, just a slight decrease in the weight near the edge is observed. Besides, the reconstructed edge of the conduction band looks likely spreading over the gap. It is remarkable to find that, although p and d characters at the valence band edges are similarly mixed in both materials in the ground state, the edge behaviors are obviously different from each other in TRPES. Schematics of band reconstructions of NiO and CuO are sketched in Fig. 1e, f.

a, b DOS of NiO and CuO. c, d Spectra of TRPES of NiO and CuO at τd = −9.8 and 13.4 fs. Dashed lines denote the band gap in the ground state \(E_{\rm{g}}^0\). \(E_{\rm{g}}^0\) of NiO and CuO are given by 4.43 and 1.44 eV (see Table S1), respectively. e, f Schematics of the band reconstruction induced by the optical pump in NiO and CuO. In the calculation of the angle-integrated spectra, a slow variation of the matrix element to remain after completing an angle integration is neglected.

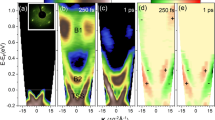

Real-time dynamics are demonstrated through the spectra of TRPES at τd = −4.9, −2.4, 0, 2.4, 4.9 fs shown (Fig. 2a, b). We keep track of a reconstruction of the valence and conduction band edges for NiO and CuO, which are marked by V and C, respectively. According to Fig. 2c, as time goes, both edges V and C of NiO are clearly shown to proceed to the inside of the gap and make in-gap states, as previously discussed in Fig. 1. Experiments of 1T-TaS26, TbTe37, 1T-TiSe28, VO211, and cuprates16 have actually reported inward shifts of LHBs, which result in a formation of forbidden mid-gap states. In the sense, a reduction of the gap could be regarded as intrinsic in correlated d bands under the optical pumping. In Fig. 2d, on the other hand, V of CuO in fact shows no noticeable shift even though C moves similarly to NiO. Moreover, the two-dimensional plots of spectra of TRPES clearly identify the retardation time τret to reach a reconstruction of the electronic structure (Fig. 2e, f). Hence, those dynamics of the band edges make us stride toward that NiO is dynamically MHI-like and CuO is dynamically CTI-like.

a, b Spectra of TRPES of NiO and CuO at τd = −4.9, −2.4, 0, 2.4, 4.9 fs. A typical position of the valence band edge is represented by V, whereas a peak position of the conduction band edge by C. In the inset of a, zoomed spectra near the conduction band edges of NiO are given and arrows indicate peaks. c, d Time-resolved behavior of V and C of NiO and CuO. e, f Two-dimensional plots (in logarithmic scales) of spectra of TRPES of NiO and CuO.

Different behaviors in the valence band edge between NiO and CuO are then further analyzed through the orbital-resolved spectra of TRPES (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, the orbital-resolved spectra tell us that, due to the probable p–d hybridization, the oxygen p band of NiO is d-like and the Cu d band of CuO is p-like. In addition, exact diagonalization studies of the many-body model Hamiltonian evidently support our conclusion. We now propose a model Hamiltonian H comprising H0 and H1, where H0 describes the one-dimensional crystalline solid

and H1 the dynamical process of TRPES

Here \(c_{i\sigma }^ +\) (ciσ) is an electron creation (annihilation) operator at the ith site with its spin σ and similarly \(c_{{\mathbf{k}}\sigma }^ +\) or ckσ a photoelectron operator with its energy εk = k2/2 and spin σ. niσ(=\(c_{i\sigma }^ +\)ciσ) is the electron number operator. t implies the nearest neighbor hopping and U the on-site Coulomb repulsion. μ is the chemical potential and Δ the ionic potential. Pump and probe terms of H1 are \(V_{{\mathrm{pump}}}\left( \tau \right) = itV_{{\mathrm{pump}}}^0{\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega _{{\mathrm{pump}}}} \right)\mathop {\sum}\limits_{i\sigma } {\left( {c_{i\sigma }^ + c_{i + 1\sigma } - c_{i + 1\sigma }^ + c_{i\sigma }} \right)}\) and \(V_{{\mathrm{probe}}}\left( \tau \right) = V_{{\mathrm{probe}}}^0{\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega _{{\mathrm{probe}}}} \right)\mathop {\sum}\limits_{i\sigma } {\mathop {\sum}\limits_{\mathbf{k}} {\left( {c_{i\sigma }^ + c_{{\mathbf{k}}\sigma } + c_{{\mathbf{k}}\sigma }^ + c_{i\sigma }} \right)} }\), respectively, with \({\mathrm{{\Phi} }}\left( {\tau ,\omega } \right) = \cos \left( {\omega \tau } \right)\cos ^2(\pi \tau {\mathrm{/}}2\bar \tau ){\mathrm{{\Theta} }}(\bar \tau - |\tau |)\). Here Θ(x) is the Heaviside step function and \(\bar \tau\) is adopted as 4.9 and 2.4 fs for the pump and probe pulses, respectively. Further, \(V_{{\mathrm{probe}}}^0{\mathrm{/}}V_{{\mathrm{pump}}}^0 \ll 1\) and \(V_{{\mathrm{pump}}}^0 = 0.5\) is assumed.

In Fig. 3a–d, Δ = 0 and U/t = 5 is taken and H0 then falls to the N-site (N = 6) Hubbard model. Figure 3a–c provide the spectral functions of N (i.e., half-filling), N + 1, and N − 1 electrons, respectively. At half-filling, the spectral function shows a Hubbard gap \(E_g^0\) (=3.6 eV) opened between the UHB and the LHB (Fig. 3a). This defines a correlated insulator corresponding to the prototype of the MHI. The (N + 1)-electron spectral function shows that, when adding an electron to the N-electron system, the electron does not jump simply into the N-electron conduction band but into a reconstructed state (marked by “e”) just below the conduction band (Fig. 3b). Similarly, when adding a hole to the N-electron state, the hole does not stay in the N-electron valence band but instead prefers a reconstructed state (marked by “h”) just above the valence band (Fig. 3c). TRPES incorporates an optical doping (i.e., a simultaneous creation of electron and hole due to the optical pumping) and naturally involves both features of (N + 1)- and (N − 1)-electron spectral functions, i.e., both of “e” and “h”, which clearly explains inward shifts of the conduction and valence edges into the gap as schematically drawn in Fig. 2e of the main text. Figure 3d gives the spectra of TRPES and PES, whose calculation can be done by extending the many-body Hilbert space to include the photoelectron under the total Hamiltonian H(=H0 + H1)23. Spectra of TRPES show well the conjugated feature of (N + 1)- and (N − 1)-electron spectra, which confirms the discussion above. In a sense, on the other hand, since non-excited electron states (i.e., N-electron states) still remain, TRPES may be approximately viewed as an addition of (N + 1)- and (N − 1)-electron spectral functions on an existence of N-electron function. Besides, it is seen that the configuration interaction between (N + 1)-and (N − 1)-electron states leading to a formation of exciton would be more or less negligible in a small size Hubbard model. Figure 3e–h treat H0 with U = 0 and 2Δ/t = 5, which describes an ordinary semiconducting material. As illustrated in Fig. 3e–g, it is seen that, when adding either an electron or a hole to the N-electron system, the band edges behave rigidly because electrons or holes are not correlated with each other. Of course, such rigid behaviors of band edges are clearly assessed in TRPES of Fig. 3h. With this observation, it becomes more strengthened that the dynamical response of NiO and CuO would be MHI-like and CTI-like, respectively.

a–d Exact diagonalization study of the N-site (N = 6) Hubbard Hamiltonian with U/t = 5(Δ = 0). a Spectral function of N electrons, i.e., at half-filling (\(E_{\rm{g}}^0\) = 3.6 eV). b Spectral function of N + 1 electrons. c Spectral function of N − 1 electrons. d Spectra of TRPES (blue) at τd = 9.8 fs and PES (red) of N electrons. e–h Exact diagonalization study of the N-site semiconducting model with 2Δ/t = 5 (U = 0). e Spectral function of N electrons (\(E_{\rm{g}}^0\) = 5.4 eV). f Function of N + 1 electrons. g Spectral function of N − 1 electrons. h Spectra of TRPES (blue) and PES (red) of N electrons. Binding energies in d, h are measured from the valence band edge of the conventional PES.

Quantum-phase-dressed excited states of graphene

During the past decades, the angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) has been the most direct and powerful method for an investigation of two-dimensional solids in their reciprocal lattices. An extension of ARPES along the time dimension is the time-resolved ARPES (TR-ARPES). Because TR-ARPES can track the q-dependent electronic structure in the manifold of energy and time and provide a wealth of real-time quantum information on the electronic dynamics, it should be a powerful tool especially for the two-dimensional semiconducting systems. Here we demonstrate the photoinduced real-time electron dynamics of the Dirac cone of graphene through an angle-resolved mode of TRPES, i.e., \(J_{\mathbf{k}}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right) = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{n,{\mathbf{q}}} {\left| {c_{\mathbf{k}}^{n,{\mathbf{q}}}\left( {\tau _{\rm{d}}} \right)} \right|^2}\). In the calculation, the LDA is adopted for the exchange and correlation potential.

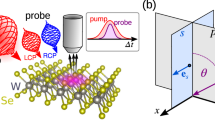

ARPES has a merit in observing the quantum phase absorbed in the matrix element, for instance, the Berry phase38 and non-equilibrium carrier dynamics39 for graphene. Taking ωprobe = 35 eV, we provide the momentum–energy distribution curves (MEDCs) of ARPES, i.e., the band mapping, of graphene (Fig. 4a, b) and electron-doped (n-type) graphene (Fig. 4c, d) along the K′ − Γ − K direction and the \({\hat{\mathbf q}}_{\mathrm{y}}\)-direction through the K point. In MEDCs, not only the massless Dirac bands cutting the Fermi level but also low-lying 2s-like bands are shown (Fig. 4a–d). In Fig. 4e, f, schematics of two Dirac cones centered at K′ and K points with relevant pseudospins near the zero binding energies are depicted. Matrix elements for ARPES, which contain the information on the Berry phase38, make a characteristic selection for the Dirac cones such that only half (blue-colored conical section) of the lower or the upper Dirac cone along the \({\hat{\mathbf q}}_{\mathrm{x}}\)-direction through the K′ or K point survives for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized probe pulse (Fig. 4a, c, e, f). Different phases of pz orbitals from two carbon atoms characteristically cancel the matrix element for the photoelectron state |k〉40,41 depending on whether it is emitted from the lower or the upper Dirac cone. Along the \({\hat{\mathbf q}}_{\mathrm{y}}\)-direction through the K point, however, the full Dirac cones are signaled in Fig. 4b, d. Moreover, taking ωpump = 3 eV and \(E_{\rm{pump}}^{0} = \omega _{\rm{pump}}A_{\rm{pump}}^{0} = 0.1\,{\rm{V}}{\AA}^{-1}\), we provide MEDCs of TR-ARPES of graphene at a fixed delay time τd = 7 fs along the \({\hat{\mathbf q}}_{\mathrm{y}}\)-direction through the K point for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump (Fig. 4g) and the K′ − Γ − K direction for the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (Fig. 4i) and the constant energy mappings (at EB = 1.5 eV (>0), i.e., in the upper Dirac cone) in the crystal momentum space for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (Fig. 4h) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (Fig. 4j). TR-ARPES captures the physics of dynamical quantum phases of the excited electron or hole states through the pseudospin correlation. Pseudospins of the Dirac cones are definitely coupled with the optical transition (Fig. 4k, l)42. Obviously, the pseudospin correlation should be considered together with the selection due to the matrix elements in determining the spectra of TR-ARPES. Consequently, vanishing nodal lines result along qy = 0 and qx = K around the K point for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized and \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pumps, respectively, in the constant energy mappings of TR-ARPES (Fig. 4h, j). This can be directly understood through a compact form of the model Hamiltonian for the Dirac cone, H0 = vFq ⋅ σ, where q is the electron wave vector, σ the Pauli matrix representing the pseudospin, and vF the Fermi velocity, is cast to H = H0 + Hint with Hint = − vFApump(τ) ⋅ σ under the optical pump. For the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump, i.e., [Hint, σx] = 0 prohibits the optical excitation at qy = 0 on the Dirac cone because σx should be reserved in the optical transition (Fig. 4k). A case for the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump could be understood in the same fashion (Fig. 4l).

a–d MEDCs of ARPES of graphene (a, b) and electron-doped n-type graphene, i.e., additional 0.6 electrons a unit cell (c, d). Geometry of the present system (inset of b). e, f Half of the Dirac cone for graphene (e) and halves of the Dirac cones for the n-type graphene (f) with nonzero matrix elements (blue-colored conical surfaces), which contain the information on the Berry phase, are captured by ARPES. Red arrows denote the pseudospin configuration. g–j Spectra of TR-ARPES of graphene at τd = 7 fs for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (g, h) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (i, j), i.e., MEDCs (g, i) and the constant energy mapping at EB = 1.5 eV (h, j). Arrows in g, i indicate the weight transfers to the conduction bands due to the optical pumping. k, l Pesudospin selection under the interband transition due to the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (k) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (l).

In Fig. 5, the time-dependent constant energy mappings of TR-ARPES of graphene focusing on the K-centered Dirac cone are displayed at τd = −7, −2.4, 0, 2.4, 7 fs. First, it is interesting to compare the spectra of ARPES of the n-type graphene with the Dirac point near −1.5 eV (Fig. 5a) with TR-ARPES of graphene from the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (Fig. 5b) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (Fig. 5c). Spectra of TR-ARPES at EB < 0 are from the lower Dirac cone with optically doped holes at ωpump = 3 eV are found to be almost same as ARPES of the n-type graphene at EB < −1.5 eV, which indicates that the valence band is in fact rigid with respect to the optical doping but a tiny reduction in the spectral weight. As previously stated, the anisotropy selecting a half of the Dirac cone with qx < K (qx > K) in the spectra of TR-ARPES at EB < 0 (EB > 0) under the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized probe pulse comes from the Berry phase involved in the matrix element. Meanwhile, the spectra at EB > 0 are from the upper Dirac cone with optically doped electrons, i.e., electrons excited to the conduction band by the pump pulse, which are inevitably carried with the pseudospin correlation. As the time delay increases, nodal lines become clear along qy = 0 and qx = K for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (Fig. 5b) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (Fig. 5c), respectively, which results from the dynamical quantum phase due to the pseudospin correlation. Spectra of ARPES of the n-type graphene would be more or less reproduced by making a summation of both of those of TR-ARPES from the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized and \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pumps.

a Constant energy mapping of ARPES of the electron-doped n-type graphene focusing on the K-centered Dirac cone. Dirac point is positioned around EB = −1.5 eV. b, c Real-time sequence of constant energy mappings of TR-ARPES of graphene focusing on the K-centered Dirac cone for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized (b) and the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump (c) at the time delays τd = −7, −2.4, 0, 2.4, and 7 fs. Spectral intensities in constant energy mappings at EB = 0.5–1.5 eV of b, c are multiplied by 4 times.

Needless to say, the dynamical quantum phase should be also incorporated in a part of the optically doped holes. We attain the difference spectra as Jk(τ1) − Jk(τ2) between the two time delays τ1 and τ2 (τ1 > τ2) in Fig. 6. For a case of the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump, the spectral differences of doped electrons (red) and holes (blue) in the constant energy mapping at EB = 1.5 eV and EB = −1.5 eV, respectively, are reasonably dispersed according to the spectra of TR-ARPES. Notably, those of doped holes have a nodal line along qy = 0 just like electrons43. Both of doped electrons and holes undergo dephasing monotonically as time goes and get to reside on well-defined Dirac cones through the energy conservation (Fig. 6b). Thus a silhouette of the full Dirac cone with the nodal line is acquired by adding the spectral differences at EB = 1.5 eV (electrons) and EB = −1.5 eV (holes) in Jk(7 fs) − Jk(2.4 fs) (Fig. 6c). For the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump, doped electrons and hole-like negative-EB signals (i.e., instead of “doped holes,” due to a reason to be cleared soon) are definitely unbalanced in their spectral densities (Fig. 6d) even if, for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump, the charge neutrality of the doped carriers is reasonably maintained. Furthermore, the hole-like negative-EB signals are found not to have a nodal line along qx = K, either. These indicate that such signals at the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump should not be due solely to the optical doping. Let us note that, in our geometry, the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump is along the armchair direction of graphene so that it could efficiently accelerate pz-orbitals belonging to a pair of neighboring carbon atoms along the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-direction. In this consideration, the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump breaks the C3 rotational symmetry of the system and gives rise to a real-time moving of the Dirac cone44. In fact, a gliding shift of the Dirac cone outward the Brillouin zone along the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-direction is found for the static field along the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-direction (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 8). Therefore, broad hole-like negative-EB signals around the edge of the hexagon (Fig. 6d) indicate a decrease (blue) and an increase (red) in the electronic states in the momentum space at EB = −1.5 eV according to a continuous field-induced moving of the Dirac cone beyond the K-point along the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-direction (Fig. 6f), which would be clear in the difference spectra of MEDCs in Fig. 7a–c (also see Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Area of the Brillouin zone in consideration. b Difference spectra of constant energy mappings of TR-ARPES as Jk(τ1) − Jk(τ2) between the two time delays τ1 and τ2 (τ1 > τ2) for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump. c Silhouette of the full Dirac cone with the nodal line of ky = 0 from an addition of difference spectra at EB = 1.5 eV and EB = −1.5 eV for the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-polarized pump. d Difference spectra for the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump. e Difference spectra between with and without the static field Efield \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\) at EB = 0 eV (Supplementary Fig. 8). Dirac cone of graphene undergoes an outward shift along the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-direction as well as a gliding shift along the static field (∝\(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)). For the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized optical pump, only the outward shift along the \({\hat{\mathbf x}}\)-direction would remain in an approximate sense. f Field-induced moving (δκ) of the Dirac cone with respect to the time delay at the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump.

a–c Different spectra of MEDCs, i.e., Jk(τ1) − Jk(τ2) (τ1 > τ2) for the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump. Schematics on right panels represent time-dependent movings of Dirac cones at K′ and K. Black and red arrows indicate the field-induced moving of Dirac cones and the interband optical transitions, respectively. d, e Tight-binding model calculation of graphene. d A model calculation for the outward gliding shift of the Dirac cone. Red and Blue band structures represent symmetry conserved (i.e., γ = 1; equilibrium) and symmetry broken (i.e., γ = 1.1; nonequilibrium) states, respectively. Here, γ is a symmetry breaking parameter. The inset displays schematics of the gliding shifts of Dirac cones. e Estimation of δκ (Fig. 6f) with respect to values of γ.

Difference spectra of MEDCs from TR-ARPES (Fig. 7a–c) show the overall dynamics of Dirac cones in a clearer fashion. At the first stage under the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump pulse (Fig. 7a), together with the optical doping between conduction and valence bands, Dirac cones are found to glide toward the outward direction of K′ and K. In the intermediate time delays (Fig. 7b), Dirac cones seem to remain temporarily at the displaced positions. At the final stage (Fig. 7c), Dirac cones return to their original positions at K′ and K. A gliding shift of the Dirac cone is discussed previously in relation to a breaking of the C3 rotational symmetry. This can be reproduced by a simple tight-binding Hamiltonian for graphene given by

where \({\Delta} _{\mathbf{k}} = - t_0({\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_1} + {\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_2} + {\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_3})\) and an is the unit vector to the nearest neighbor C atom and t0 (=3 eV) is the hopping (or hybridization) parameter. Here, assuming a3 ∥ \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\), a strong pump field along the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-direction would immediately render a hybridization strength between C atoms along the a3-direction to increase. That is, in the new Hamiltonian, Δk may be replaced by \({\Delta} _{\mathbf{k}} = - t_0\left( {{\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_1} + {\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_2}} \right) - \gamma t_0{\mathrm{e}}^{i{\mathbf{k}} \cdot {\mathbf{a}}_3}\), where γ will be regarded as a symmetry breaking parameter in the hybridization between the nearest neighbor C atoms along \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-direction, that is, at γ = 1, graphene recovers the C3 rotational symmetry, i.e., an equilibrium state, whereas at γ > 1, the symmetry is broken under the \(\widehat {\mathbf{y}}\)-polarized pump pulse. In Fig. 7d, e, γ is found to linearly result in outward glidings of Dirac cones of K′ and K, respectively, and γ ~ 1.02 to induce δκ consistent with TR-ARPES of Figs 6e, f and 7a–c.

The present calculation has been performed based on the single-body equation with the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, but the adiabatic Born–Oppenheimer approximation is recognized not to be valid in graphene45. Here it is stressed that a gliding shift of the Dirac cone is originated by a breaking of the sixfold rotation symmetry of the sp3 hybridization due to the optical pumping, not an instantaneous change of atomic positions. Therefore, we still expect that the gliding would be observed at least during the optical pumping, i.e., the external optical perturbation may overwhelm the phonon-related underlying process. What would happen after the optical pump field has passed will be an interesting question due to the nonadiabatic electron–phonon coupling.

Discussion

In the first-principles framework, we have explored an original theory of TRPES or TR-ARPES for infinitely periodic solids and examined the real-time electron spectra focusing on the excited valence band edges of strongly correlated electron systems and the quantum-phase-dressed excited states of a two-dimensional semiconductor graphene. In strongly correlated systems, dynamics of valence band edges under a strong optical pump have been found to be very different between NiO and CuO. This could provide a critical insight to the dynamical aspect of the ZSA scheme, from which we claim that NiO dynamically behaves like the Mott–Hubbard system and CuO like the charge transfer system. In graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms, excited states dressed with the Berry curvature, and the pseudospin correlation have been thoroughly tracked in the angle-resolved mode. Particularly, the dephasing dynamics of optically doped electrons and holes on the Dirac cone, more intricately on a field-induced moving of the Dirac cone, have been discovered in the real-time domain.

Methods

First-principles calculations

Calculations for initial ground states were computed by using the all-electron linearized augmented planewave (APW) method implemented in ELK (see http://elk.sourceforge.net) code. First order of extra radial function is added to the local orbitals and APWs. The maximum length for the momentums multiplying averaged muffin-tin radius is fixed to be 8.0. The reciprocal lattice vector cutoff for the electron density and potential is 12 atomic unit. For the calculation of CuO and NiO, we performed the spin-polarized calculation and TB-mBJLDA DFT with sampling of the first Brillouin zone of 4 × 4 × 4. We confirmed the convergence of the time evolution until 8 × 8 × 8. For graphene, the LDA is adopted together with the first Brillouin zone sampling 27 × 27 × 1. The time-step interval for the time-evolution calculation is fixed to 0.1 atomic unit.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tokura, T. Photoinduced phase transition: a tool for generating a hidden state of matter. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 011001 (2006).

Yonemitsu, K. & Nasu, K. Theory of photoinduced phase transitions in itinerant electron systems. Phys. Rep. 465, 1 (2008).

Chollet, A. et al. Gigantic photoresponse in ¼-filled-band organic salt (EDO-TTF)2PF6. Science 307, 86 (2005).

Kim, K. W. et al. Ultrafast transient generation of spin-density-wave order in the normal state of BaFe2As2 driven by coherent lattice vibrations. Nat. Mater. 11, 497 (2012).

Mitrano, M. et al. Possible light-induced superconductivity in K3C60 at high temperature. Nature 530, 461 (2016).

Perfetti, L. et al. Time evolution of the electronic structure of 1T−TaS2 through the insulator-metal transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067402 (2006).

Schmitt, F. et al. Transient electronic structure and melting of a charge density wave in TbTe3. Science 321, 1649 (2008).

Rohwer, T. et al. Collapse of long-range charge order tracked by time-resolved photoemission at high momenta. Nature 471, 490 (2011).

Petersen, J. C. et al. Clocking the melting transition of charge and lattice order in 1T−TaS2 with ultrafast extreme-ultraviolet angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 177402 (2011).

Graf, J. et al. Nodal quasiparticle meltdown in ultrahigh-resolution pump–probe angle-resolved photoemission. Nat. Phys. 7, 805–809 (2011).

Wegkamp, D. et al. Instantaneous band gap collapse in photoexcited monoclinic VO2 due to photocarrier doping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 216401 (2014).

Piovera, C. et al. Time-resolved photoemission of Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 93, 241114(R) (2016).

Lantz, G. et al. Ultrafast evolution and transient phases of a prototype out-of-equilibrium Mott–Hubbard material. Nat. Commun. 8, 13917 (2017).

Ligges, M. et al. Ultrafast doublon dynamics in photoexcited 1T-TaS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 166401 (2018).

Zong, A. et al. Evidence for topological defects in a photoinduced phase transition. Nat. Phys. 15, 27 (2019).

Cilento, F. et al. Dynamics of correlation-frozen antinodal quasiparticles in superconducting cuprates. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar1998 (2018).

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039 (1998).

Rameau, J. D. et al. Photoinduced changes in the cuprate electronic structure revealed by femtosecond time- and angle-resolved photoemission. Phys. Rev. B 89, 115115 (2014).

Freutel, S. et al. Optical perturbation of the hole pockets in the underdoped high-Tc superconducting cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 99, 081116(R) (2019).

Freericks, J. K., Krishnamurthy, H. R. & Pruschke, T. Theoretical description of time-resolved photoemission spectroscopy: application to pump-probe experiments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 136401 (2009).

Sentef, M. et al. Examining electron-boson coupling using time-resolved spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. X 3, 041033 (2013).

Sentef, M. A. et al. Theory of Floquet band formation and local pseudospin textures in pump-probe photoemission of graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 7047 (2015).

Lee, J. D. & Inoue, J. Photoinduced Hubbard band mixing due to ultrafast laser irradiation of a one-dimensional Mott insulator. Phys. Rev. B 76, 205121 (2007).

Giovannini, U. D. et al. Ab initio angle- and energy-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy with time-dependent density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. A 85, 062515 (2012).

Giovannini, U. D., Hübener, H. & Rubio, A. Monitoring electron-photon dressing in WSe2. Nano Lett. 16, 7993 (2016).

Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Accurate band gaps of semiconductors and insulators with a semilocal exchange-correlation potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 226401 (2009).

Zaanen, J., Sawatzky, G. A. & Allen, J. W. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 418 (1985).

Damascelli, A. Probing the electronic structure of complex systems by ARPES. Phys. Scr. 109, 61–74 (2004).

Mott, N. F. The basis of the electron theory of metals, with special reference to the transition metals. Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond. Sect. A 62, 416 (1949).

Hubbard, J. Electron correlations in narrow energy bands. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 276, 238 (1963).

Sawatzky, G. A. & Allen, J. W. Magnitude and origin of the band gap in NiO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 53, 2339 (1984).

Hüfner, S., Steiner, P., Sander, I., Neumann, M. & Witzel, S. Photoemission on NiO. Z. Phys. B Condensed Matter 83, 185–192 (1991).

Fujimori, A., Minami, F. & Sugano, S. Multielectron satellites and spin polarization in photoemission from Ni compounds. Phys. Rev. B 29, 5225(R) (1984).

Shen, Z.-X. & Dessau, D. S. Electronic structure and photoemission studies of late transition-metal oxides-Mott insulators and high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rep. 253, 1–162 (1995).

Schuler, T. M. et al. Character of the insulating state in NiO: A mixture of charge-transfer and Mott-Hubbard character. Phys. Rev. B 71, 115113 (2005).

Ren, X. et al. LDA + DMFT computation of the electronic spectrum of NiO. Phys. Rev. B 74, 195114 (2006).

Ghijsen, J. et al. Electronic structure of Cu2O and CuO. Phys. Rev. B 38, 11322 (1988).

Hwang, C. et al. Direct measurement of quantum phases in graphene via photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 84, 125422 (2011).

Gierz, I. et al. Snapshots of non-equilibrium Dirac carrier distributions in graphene. Nat. Mater. 12, 1119–1124 (2013).

Alperin, H. A. The Magnetic Form Factor of Nickel Oxide. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 17, 12–17 (1962).

Puschnig, P. & Lüftner, D. Simulation of angle-resolved photoemission spectra by approximating the final state by a plane wave: from graphene to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules. J. Electr. Spect. Relat. Phenom. 200, 193–208 (2015).

Echtermeyer, T. J. et al. Photothermoelectric and photoelectric contributions to light detection in metal–graphene–metal photodetectors. Nano Lett. 14, 3733 (2014).

Aeschlimann, S. et al. Ultrafast momentum imaging of pseudospin-flip excitations in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 96, 020301(R) (2017).

Jia, T.-T. et al. Dirac cone move and bandgap on/off switching of graphene superlattice. Sci. Rep. 6, 18869 (2016).

Pisana, S. et al. Breakdown of the adiabatic Born–Oppenheimer approximation in graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 198–201 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program (2019R1A2C1005050) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and also by the DGIST R&D program (20-CoE-NT-01), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D.L. materialized the research idea and Y.K. performed the theoretical calculation. Y.K. and J.D.L. wrote the manuscript, discussed the results, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Lee, J. Time-resolved photoemission of infinitely periodic atomic arrangements: correlation-dressed excited states of solids. npj Comput Mater 6, 132 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00398-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00398-0

This article is cited by

-

Topological quantum materials for energy conversion and storage

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)