Abstract

The hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites (HOIPs) have attracted much attention for their potential applications as novel optoelectronic devices. Remarkably, the Rashba band splitting, together with specific spin orientations in k-space (i.e., spin texture), has been found to be relevant for the optoelectronic performances. In this work, by using first-principles calculations and symmetry analysis, we study the electric polarization, magnetism, and spin texture properties of the antiferromagnetic (AFM) ferroelectric HOIP TMCM-MnCl3 (TMCM = (CH3)3NCH2Cl+, trimethylchloromethyl ammonium). This recently synthesized compound is a prototype of order–disorder and displacement-type ferroelectric with a large piezoelectric response, high ferroelectric transition temperature, and excellent photoluminescence properties as reported by You (Science 357:306, 2017). The most interesting result is that the inversion symmetry breaking coupled to the spin–orbit coupling gives rise to a Rashba-like band splitting and a related robust persistent spin texture (PST) and/or typical spiral spin texture, which can be manipulated by tuning the ferroelectric or, surprisingly, also by the AFM order parameter. The tunability of spin texture upon switching of AFM order parameter is largely unexplored and our findings not only provide a platform to understand the physics of AFM spin texture but also support the AFM HOIP ferroelectrics as a promising class of optoelectronic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The past few years witnessed the extremely rapid development of hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites (HOIPs), which have been shown to be promising optoelectronic materials1,2,3,4,5. HOIP materials have several commom features, including the classical \({\mathrm{ABX}}_3\) perovskite architecture and the presence of organic cation that occupy the A-site. As for the B-site, it can be occupied not only by main group elements, but also by transition metal atoms such as Mn and Fe, thus introducing magnetic degrees of freedoms into the compound. As for the X-site, it is usually the halogen element. The HOIP materials have some advantages and, in particular, the exceptionally long carrier lifetimes make them very attractive for optoelectronic devices, such as light absorbers and light-emitting diodes6,7,8,9,10,11.

To further enhance the optoelectronic performances of HOIP materials, intense research has been directed to explain the microscopic origin of the long lifetimes9,10,11. Recently, the presence of Rashba band splitting has been suggested to be connected with the carrier lifetimes and to improve their optoelectronic performances12,13,14,15. When lacking spatial inversion symmetry, the spin–orbit coupling (SOC) leads to an effective momentum-dependent magnetic field \({\vec{\mathrm \Omega }}( {\vec k})\) acting on the spin \(\vec \sigma\) and the effective SOC Hamiltonian can be written as \(H_{SO} = {\vec{\mathrm \Omega }}( {\vec k})\! \cdot \! \vec \sigma\) 16,17. In this case, the SOC will split the spin degeneracy with specific spin orientations (i.e., spin texture) in the momentum k-space, as was first demonstrated by Rashba18 and Dresselhaus et al.19. The spin texture can often be manipulated and even reversed by switching the electric polarization under external electric field, leading to an all-electric and non-volatile control of the spin state20,21,22,23,24. Rashba effects were mainly discussed in non-magnetic lead halide perovskites9,10,11,12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27,28 or non-magnetic ferroelectric (FE) semiconductors20,21,22,23,29,30,31,32,33,34. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies on the spin texture in AFM FE HOIPs. Furthermore, antiferromagnets are very appealing for spintronic applications due to their superior properties, as they produce no stray fields and display intrinsic ultrafast spin dynamics35,36,37. In the last few years, intense theoretical and experimental research have shown that it is possible to realize electric-field control of magnetism in multiferroic materials38,39,40,41. The couplings between polarization, magnetism, and spin textures are still largely unexplored but they could have important applications in magneto-optoelectronic devices. Indeed, some recent reviews have pointed out intriguing spin-optotronic properties in HOIP materials42,43. Therefore, it is interesting to study whether there exists unusual Rashba effects in AFM FE HOIPs and how to manipulate the spin textures.

In this work, we start by considering the compound of TMCM-MnCl3 (TMCM = (CH3)3NCH2Cl+, trimethylchloromethyl ammonium). In 2017, You et al.44 reported that TMCM-MnCl3 is a FE material that shows an excellent piezoelectric response (d33 = 185 pC/N) that is close to that of inorganic piezoelectrics such as BaTiO3 (d33 = 190 pC/N) and a high transition temperature Tc of 406 K. Besides, TMCM-MnCl3 displays excellent photoluminescence properties, with a near-unity photoluminescence emission efficiency44. In our study, we discuss the interplay among FE and magnetic orderings, and spin textures by using density functional theory (DFT). We show that TMCM-MnCl3 is a prototype of order–disorder and displacement-type FE whose polarization can be greatly modified by the halogen atom substitutions. The most important result is that a Rashba-like effect in the band structure leads to robust unidirectional persistent spin texture (PST) and/or spiral spin texture31,45. The spin textures have been predicted to support an extraordinarily long spin lifetime, which is promising for optoelectronic devices46,47. By tuning the FE or, surprisingly, the antiferromagnetic order parameter, we find that the spin texture can be modified significantly. Our results indicate that not only the electric but also the magnetic field can effectively be used to manipulate the spin textures even in AFM but polar HOIP materials such as TMCM-MnCl3. Our results suggest that AFM FE HOIPs is an interesting class of materials that deserves further study.

Results

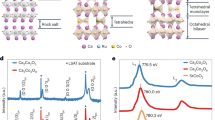

At high temperature, TMCM-MnCl3 adopts a paraelectric phase with centrosymmetric space group P63/mmc with disordered organic cations. However, as the temperature decreases, TMCM-MnCl3 undergoes an order–disorder phase transition at around 406 K and crystallizes into the polar Cc phase44. To find the experimental ground-state structure, we rotate the organic cations randomly to consider different configurations and then optimize these structures to calculate their total energies. In our work, we generate about 100 random structures and find that the Cc phase indeed has the lowest total energy, in agreement with the experimental result. It has a monoclinic conventional cell with the distortion angle between a and c axis about 95°. Our optimized lattice constants are a = 9.371, b = 15.548, and c = 6.521Å which are consistent with the experimental report of a = 9.478, b = 15.741, and c = 6.577 Å. As shown in Fig. 1, TMCM-MnCl3 contains four organic cations and four Mn ions in the conventional cell. Their crystal packing is similar to BaNiO3-like perovskite. The Mn ions form the inorganic chains along [001] direction with the ligand ions of Cl, whereas the organic cations are inserted between these inorganic chains. One can see that the freezing of polar organic cations can give rise to the FE polarization along approximately the [10\(\bar 1\)] direction. From crystallographic analysis, it has 6 different polar axes with 12 possible orientations of polarization. This multiaxial characteristic is certainly interesting for fundamental research and practical applications of FE HOIPs48.

The ground-state Cc phase is shown from the top (a) and side (b) views, respectively. The magnetic configuration of G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) (\({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y) state is shown in b. The AFM order parameter is defined as \({\mathbf{L}} ={\sum \nolimits_{\boldsymbol{i}}} {\mathbf{S}}^{\boldsymbol{i}} -{\sum \nolimits_{\boldsymbol{j}}} {\mathbf{S}}^{\boldsymbol{j}}\), where \({\mathbf{S}}^i\) (\({\mathbf{S}}^j\)) is the spin moment along the positive (negative) axis, respectively. Here, \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y denotes G-type AFM state with AFM order parameter (L) along y [010] axis. The red arrows represent the local moment, which is set to be along the y direction. The polarization is along approximately [10\(\bar 1\)] direction with Px ~ 4.18 μC/cm2 and Pz ~ 4.48 μC/cm2.

To study FE properties, we apply the modern theory of electric polarization49,50. The details of DFT calculations are described in “Methods.” To simulate the antiferroelectric (AFE)–FE transition, we fix two organic cations and rotate the other two cations by introducing an interpolating parameter λ (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1)51,52,53. It is noteworthy that this dimensionless parameter λ is not the usual linear interpolation for atomic positions but it defines the correlated rotation of cations as well as the displacement of the MnCl3 framework. Therefore, it represents the normalized amplitude of the roto-displacive path. As the transition path is artificially assigned to act as a computational tool, the polarization difference between λ = 1 and λ = 0 states has a real physical meaning. Here we define our convention for the coordinates as the x (y) axis being along a (b) axis, respectively. As for the z axis, it is vertical to the x–y plane and it has an angle about 5° with the c axis. In TMCM-MnCl3 system, the polarization is evaluated to be 6.12 μC/cm2 approximately along the [10\(\bar 1\)] direction (Px is about 4.18 μC/cm2 and Pz is about −4.48 μC/cm2), which is in rather good agreement with the experimental value of Pz ~ 4.00 μC/cm2 44. To shed light into the microscopic mechanism of FE polarization, we perform mode decomposition54 with respect to the reference centric phase by considering the different functional units, i.e., organic cations and framework. This approach, called functional mode analysis, has been already used for the analysis of FE polarization in hybrid compounds. Here, functional refers to functional units in the HIOPs, i.e., organic cations and framework. It is useful to disentangle the different contributions to the total polarization by considering the role played by the different functional units. We find that the polarization contains two main contributions, one is from the organic cations about 4.87 μC/cm2 and the other part comes from the distortion of the inorganic framework, which is about 1.15 μC/cm2. The first contribution can be associated to the ordering of the organic cations, whereas the second one can be related to a significant displacement-type contribution. Therefore, TMCM-MnCl3 is a prototype as order–disorder and displacement-type FE.

The halogen atoms and H atoms can form a complex hydrogen bonding network with the organic cations, which mainly determine the relative orientations of the organic cations with respect to the framework. Therefore, it may be useful to study how the halogen substitutions may influence the FE polarization. Indeed, the halogen atoms have similar chemical properties, but they differ in electronegativity, which, in turn, will effectively change the electric polarization through hydrogen bond network that is responsible for the complex cations and framework interaction. By changing the halogen atoms in the inorganic framework and/or organic cations, we find that the polarization can be significantly modified (see Supplementary Figs 2–3).

As for the magnetic ground state, we performed collinear calculations showing that TMCM-MnCl3 has strong AFM interaction within the inorganic MnCl3 chains. This can be understood in terms of Goodenough–Kanamori rule, which predicts a strong AFM super-exchange interaction between two half-filled \(Mn^{2 + }\) (3d5) ions55,56. However, the interchain interaction between the inorganic MnCl3 chains is weak AFM, as the distance between neighboring chains is large (>9 Å). The energy of different magnetic configurations is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The G-type AFM state is the ground state with AFM intrachain and interchain couplings. To accurately evaluate the spin coupling parameters, we adopt a four-state method57,58. The effective spin exchange J for the intrachain Mn–Mn pair is computed to be 12 meV, whereas the interchain interaction is about 0.1 meV. When considering the SOC effect, the non-collinear calculations show that the local spin moments tend to be perpendicular to the MnCl3 chains and the magnetic anisotropy energy is about 0.03 meV/Mn. We note that there is no relevant canting of spins in TMCM-MnCl3 system, i.e., we have a collinear AFM HOIPs compound. Considering that TMCM-MnCl3 has weak interchain interaction, one can apply external fields (e.g., magnetic field) to switch the spins along one direction, i.e., C-type AFM state (intrachain AFM coupling and interchain FM coupling). Therefore, considering the tunable FE and magnetic states, the TMCM-MnCl3 system provides an ideal platform to investigate the interplay between FE ordering, magnetic ordering, and spin textures.

We investigate the electronic properties of valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) by calculating the band structures with/without SOC (see Figs 2a-d). Here, the conventional cell contain four organic cations and four Mn ions (see Fig. 1). When considering SOC, the spin moment is set to be along y axis. The band structures of G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) and C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) states are shown in Fig. 2b, d, respectively. To help understand the spin textures discussed in the following paragraphs, we choose a specific symmetric k-path containing \(k_b\) and \(k_{ac}\), which is perpendicular to the polarization (see Fig. 2e, f)23,31,32,59. Here, \(k_b\) and \(k_{ac}\) denote the \(k\) path from \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) (0,0,0) to \({\mathrm{Y}}\) (0,0.5,0) and \({\mathrm{Q}}\) (0.5,0,0.5), respectively. To simplify the illustration of Brillouin zone, we simplify the crystal lattice from slightly monoclinic to orthorhombic (see Fig. 2f). For G-type AFM state (see Fig. 2a), our calculations show that the VBM and CBM are located at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point and the partial density of states (DOS) show that the valence band edge contains contributions from Mn-3d and Cl-2p orbitals, whereas the conduction band edge is mainly composed of Mn-3d orbitals (see Supplementary Fig. 5). Due to the symmetry (see below for detailed analysis), all eigenstates are at least twofold degenerate (i.e., spin-up and spin-down states). When taking SOC into account, the Rashba–Dresselhaus effect removes the spin degeneracy into singlets along the symmetry path but it still keeps twofold degeneracy at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point (see Fig. 2b). Interestingly, for the C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}\) state, the doublet at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point splits into two singlets with a sizable spin splitting at VBM about 0.027 eV after inclusion of SOC (see Fig. 2d).

We discuss G-type AFM (a, b) and C-type AFM (c, d) without SOC (a, c) and with SOC (b, d), respectively. In b, d, the spin moment is set to be along the y direction. The abscissa is the Brillouin zone coordinate along the symmetry line and the ordinate is the energy, where the Fermi level is set to 0 eV. The magnified inset in b shows the SOC-induced band splitting around the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point. The band degeneracy at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point is represented by \({\bar{\mathrm D}}\). The crystal lattice accompanied with the mirror reflection are shown in e with the polarization along approximately [10\(\bar 1\)] direction. In f, the first Brillouin zone with the symmetry path in band structure calculations. The olive green section containing \(k_b\) and \(k_{ac}\) is adopted to draw the spin texture, where \(k_b\) and \(k_{ac}\) denote the \(k\) path from \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) (0,0,0) to \({\mathrm{Y}}\) (0,0.5,0) and \({\mathrm{Q}}\) (0.5,0,0.5), respectively.

To understand the band degeneracy at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, we perform the symmetry analysis by considering Kramers degeneracy. Considering a Hamiltonian \(\hat H\) with an eigenvector \(\psi\) and a real eigenvalue \(\lambda\) such as \(\hat H\psi = \lambda \psi\). Let \(\psi \prime = \hat A\psi\), where \(\hat A\) commutes with \(\hat H\). It’s easy to write: \(\hat H\psi {\prime} = \hat H\hat A\psi = \hat A\hat H\psi = \lambda \hat A\psi = \lambda \psi ^{\prime}\). Hence, both \(\psi\) and \(\psi^ {\prime}\) are eigenvectors of \(\hat H\) with the same eigenvalue \(\lambda\). One can prove that \(\psi\) and \(\psi {\prime}\) are orthogonal to each other if \(\hat A\) is anti-unitary and \(\hat A^2\psi = - \psi\), as \(\langle\psi ,\hat A\psi\rangle =\langle \hat A\psi ,\hat A^2\psi \rangle^{\ast}\) = \(- \langle\hat A\psi ,\psi\rangle^{\ast}= - \langle\psi ,\hat A\psi\rangle\) and thus \(\langle\psi ,\hat A\psi\rangle = 0\). Due to the orthogonality, \(\psi\) is degenerate with \(\psi {\prime} = \hat A\psi\). Therefore, if \(\hat A\) commutes with \(\hat H\) and \(\hat A^2 = - 1\), the band structure can be double degenerate. In our TMCM-MnCl3 system, the G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state has the magnetic symmetry of \(\hat M = \{ \left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}0} \right\},\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b + c}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right\}\}\), where \(E\) is identity operator, \(\hat T\) is time-reversal operator, and \(\hat m_{ac}\) is the mirror symmetry operator followed by lattice translation. We find that the operator \(\hat A_{\mathrm{b}} = \hat T\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right\}\) is anti-unitary and commutes with the Hamiltonian at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point (here, \(\hat A_{\mathrm{b}}\) plays a similar role as \(\hat T\) in the time-reversal invariant case considered by the Kramers degeneracy). The band structure of G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state is shown in Fig. 2b and we use the subscript of \(\hat A\) (i.e., b) to index the band structure. Using the properties of half-spin system at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, we can identify \(\hat A_{\mathrm{b}}^2 = \hat T^2 = - 1\), leading to twofold degeneracy at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point with SOC effect. As for C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state, it has the magnetic symmetry of \(\hat M = \{ \left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}0} \right\},\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b + c}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\}\). Different from G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state, we cannot find such an anti-unitary symmetry operator \(\hat A_{\mathrm{d}}\) to construct Kramers pair, as \(\left( {\hat T\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\tau _C} \right\}} \right)^2\psi = \hat T^2m_{ac}^2\psi = - 1\! \cdot \! \left( { - 1} \right)\! \cdot \! \psi = \psi\), where \(\tau _C = \frac{{a + b + c}}{2}\) or \(\frac{c}{2}\). Hence, the energy bands of C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) with SOC are all singlet as shown in Fig. 2d. When turning off SOC, spin is independent from the spatial degrees of freedom and pure spin rotation \(\hat U\) can be introduced to explain the energy band degeneracy60. \(\hat U\) can reverse the spin but it is unitary and keeps the momentum invariant. For collinear AFM system without SOC, the wave function \(\phi\) can be chosen to have a definite Sz value (1/2 for up-spin or -1/2 for down-spin); thus, \(\hat U\phi\) and \(\phi\) are orthogonal and form the Kramers pair. Without SOC, G-type AFM state has the symmetry of \(\hat U\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right\}\). It commutes with the Hamiltonian for all wave vectors and lead to twofold degeneracy in the whole BZ, including path \({{Q}} - {\mathrm{\Gamma }} - {{Y}}\) as shown in Fig. 2a. As for the C-type AFM state, the twofold degeneracy along \({{Q}} - {\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) and \({\mathrm{\Gamma }} - {{Y}}\) (see Fig. 2c) can be ascribed to different symmetry mechanism. The wave vectors in \({{Q}} - {\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) and \({\mathrm{\Gamma }} - {{Y}}\) respect the symmetry of \(\hat T\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\) and \(\hat U\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\), respectively. It is noteworthy that without SOC, one can get \(m_{ac}^2\psi = \psi\) and hence we can have \(\hat A_{\mathrm{c}} = \hat T\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\), \(\hat A_c^2\psi = \hat T^2m_{ac}^2\psi = - 1\! \cdot \! 1\! \cdot \! \psi = - \psi\). Therefore, both \(\hat T\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\) and \(\hat U\left\{ {m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\) can form Kramers pair and the corresponding band structure is double degenerate. Apart from these symmetry arguments, we can also apply systematic group theory analysis based on the co-representation of the magnetic point group to understand the spin degeneracy at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point (see Supplementary Note 2). These two methods give the same results. Therefore, to summarize our discussion, the different symmetry operations in G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state and C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state can lead to different band degeneracy at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point.

Knowing the spin degeneracy at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, we can consider the spin texture around this point in the Brillouin zone. Considering that TMCM-MnCl3 displays two long-range ordering, i.e., FE and AFM orderings, it is interesting to see how the spin textures behave under the interplay of these two order parameters. Recently, the electric-field control of spin textures has been shown in non-magnetic FE GeTe thin film20,21,22,23. Here, as we will show below, the spin textures in TMCM-MnCl3 can be tuned by switching not only FE ordering but also by switching the magnetic order parameter in an AFM polar HOIP. This represents a new degree of freedom to play with in the spin-texture tuning, which has been very little studied in the literature. The SOC splits the band structure into two branches, which exhibit similar spin textures but with opposite helicity or orientation. Here we will focus on the inner branches near the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, whereas the spin textures of the outer branches are illustrated in Supplementary Figs 7–17. To simplify the visualization, we project the spin textures on a specific plane, which is perpendicular to the polarization (see Fig. 2f)23,31,32,59.

In the following, we discuss the spin textures in G-type AFM state. We pay attention to the spin texture at CBM, as the spin value at VBM is small due to the weak band splitting. It is useful to introduce the AFM order parameter defined as \({\mathbf{L}} ={\sum \nolimits_{\boldsymbol{i}}} {\mathbf{S}}^{\boldsymbol{i}} - {\sum \nolimits_{\boldsymbol{j}}} {\mathbf{S}}^{\boldsymbol{j}}\), where \({\mathbf{S}}^i\) (\({\mathbf{S}}^j\)) is the spin moment along the positive (negative) axis, respectively. We use the subscript of L to define different AFM state. For example, \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y indicates the G-type AFM configuration along the y direction. In addition, we use \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ −y to indicate the operation that flip the spin from y to −y direction. The polarization (P) is along the [10\(\bar 1\)] direction, whereas −P is along the [\(\bar 101\)] direction. As we can see in Fig. 3a, it shows a robust PST at CBM. The spin is unidirectional and parallel (\(k_{ac}\) < 0) or antiparallel (\(k_{ac}\) > 0) to \(k_b\) direction (i.e., vertical to the mirror reflection). One can understand the spin texture by considering the magnetic symmetry. The G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state has the magnetic space symmetry of \(\hat M = \left\{ {\left\{ {E\left| 0 \right.} \right\},\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}\left| {\frac{{a + b + c}}{2}} \right.} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}\left| {\frac{c}{2}} \right.} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {E\left| {\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right.} \right\}} \right\}\), which can be labeled with \(\hat M = \{ \hat m,\hat T\hat m,\hat T\}\). Thus, one can have the following constraints on spin texture: \({\mathbf{S}}\left( k \right) = \hat m{\mathbf{S}}\left( {\hat mk} \right)\), \({\mathbf{S}}\left( k \right) = \hat T\hat m{\mathbf{S}}\left( {\hat T\hat mk} \right)\), and \({\mathbf{S}}\left( k \right) = \hat T{\mathbf{S}}\left( {\hat Tk} \right)\). We note that the PSTs occupy a substantial scale of Brillouin zone. It spans more than 0.04 \({\AA}^{-1}\) around the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, whereas for comparison the reciprocal wave vector of \(k_b\) is \({\uppi}/{\mathrm{b}} = 0.20\,{\AA}^{ - 1}\), which corresponds to the length of symmetry path from (0,0,0) to (0,0.5,0). In this large area, the spin configurations remain nearly unidirectional, which is favorable to support the long spin lifetime of carrier promising for optoelectronic applications31,45,46. Our results suggest that TMCM-MnCl3 is a rare example of Rashba-AFM HOIP FE with robust PST.

Here we show the spin textures at CBM. \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y (\({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ −y) present G-type AFM state with spin moment along y (−y) axis, respectively. \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ x presents G-type AFM state with spin moment along x axis. \({\mathbf{P}}\sim\) p (\({\mathbf{P}}\sim\)−p) denotes polarization along [10\(\bar 1\)] ([\(\bar 101\)]), respectively. \(k_b\) and \(k_{ac}\) denote the \(k\) path with the unit of \({\AA}^{ - 1}\). The arrows refer to the in-plane orientation of spin and the scale is shown in the top left corner, whereas colors indicate the out-of-plane component. In b, the polarization is switched to −p. In c, the magnetic ordering is switched to −y direction. In d, the magnetic ordering is switched to x direction. In e and f, we show the schematic diagrams of spin transformation. In e, the spin transformation under spatial inversion operator \(\hat I\) (i.e., the reversal of polarization). In f, the spin transformation under time-reversal operator \(\hat T\) (i.e., the reversal of AFM order parameter).

Here we discuss the interplay between FE ordering, magnetic ordering, and spin texture. In Fig. 3b, we fix the magnetic ordering but reverse the FE polarization from P to −P. One can see that the PST is reversed with the switching of the polarization. The spin transformation rule under space inversion operator \(\hat I\) is shown in Fig. 3e. When considering the spin configurations at the points \(\mathop{k}\limits^{\rightharpoonup}\) to -\(\mathop{k}\limits^{\rightharpoonup}\) related by the space inversion operator \(\hat I\) (i.e., reversal of polarization), the spin orientations remain unchanged, as \(\hat I{\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}\left( k \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\left( { - k} \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}\left( k \right)\), where P is the FE order parameter, \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\) is the new spin after the space inversion. In G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state, the spin at \(- k\) point has opposite orientation compared with the spin at \(k\) point, i.e., \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}( - k) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\), whereas after the space inversion (switching of polarization), one can get \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\left( { - k} \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\). Therefore, we can reverse the PST by switching the FE ordering. As for switching the magnetic ordering, the time-reversal operation \(\hat T\) will reverse the magnetic ordering parameter L and spin texture changes according to \(\hat T{\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}\left( k \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}\left( { - k} \right) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}\left( k \right)\), where \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}\) is the new spin after the time reversal. In Fig. 3c, we fix the FE order and then we flip magnetic ordering from \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y to \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ −y. We find the PST remains unchanged, as \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}( - k) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\) and \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}\left( { - k} \right) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\). Apart from the flip of magnetic ordering from L to −L, one can also switch the magnetic ordering to other directions. In Fig. 3d, we rotate the magnetic ordering from \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y to \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ x. Surprisingly, there is PST at not only CBM (see Fig. 3d) but also VBM in comparison with the small spin value at VBM in \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{G}}\) ~ y case (see Supplementary Note 3). The G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_x\) state has the magnetic symmetry of \(\hat M = \{ \left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}0} \right\},\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b + c}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\}\). The rotation part keeps the same with G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state but the translational part of glide plane changes. We note that the magnetic symmetry is conserved as long as the magnetic ordering lies within the ac plane, i.e., the mirror \(\hat m_{ac}\). According to the symmetry analysis, the operator \(\hat A = \hat T\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\}\) commutes with the Hamiltonian accompanied with \(\hat A^2 = \hat T^2 = - 1\) at the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, leading to twofold degeneracy at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point with SOC effect (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Our further calculations demonstrate that when we rotate the magnetic ordering within the ac plane, the PST can be switched along the magnetic ordering (see Supplementary Note 3). It is an interesting result that we can continuously rotate PST by switching the magnetic ordering. Now we can draw the conclusion that the G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}\) state shows the robust PST around the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point and the PST can be manipulated not only by switching the polarization but also by switching the magnetic ordering. This is certainly a new result, as, so far, the switching of spin-texture chirality has been linked only to the switching of FE polarization while here we point out the active role of the switching of AFM order parameter.

Now we discuss the spin textures in C-type AFM state. TMCM-MnCl3 has weak interchain interaction and one may apply external fields (e.g., magnetic field) to switch the spins along one direction, i.e., C-type AFM state. We find the PST along \(k_{ac}\) direction, although there is a deviation from the unidirectional spin orientation when moving far away from the \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point. We note that the PST in G-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state is along the \(k_b\) direction. This phenomenon shows that one can switch the PST by realizing different magnetic state. As for CBM, it exhibits spiral spin textures with clockwise helicity. This two-dimensional vector field is identical to the characteristic Rashba-like spin texture23,32,59. The C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state has the magnetic symmetry of \(\hat M = \left\{ {\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}0} \right\}} \right.,\left\{ {E{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{{a + b + c}}{2}} \right\},\hat T\left\{ {\hat m_{ac}{\mathrm{|}}\frac{c}{2}} \right\},\) which can be labeled with \(\hat M = \{ \hat T\hat m\}\). Correspondingly, the doublet state at \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point is lifted into singlets by SOC with a sizable band spin splitting at VBM about 0.027 eV (see Fig. 2d). According to the \(\hat T\hat m\) symmetry, the PST and spiral spin texture can be understood with \({\mathbf{S}}\left( k \right) = \hat T\hat m{\mathbf{S}}\left( {\hat T\hat mk} \right)\). At \({\mathrm{\Gamma }}\) point, there is no spin component along \(k_b\) direction, as \(\hat T\hat mk\)= k and \({\mathbf{S}}({\mathrm{\Gamma }}) = \hat T\hat m{\mathbf{S}}\left( {\mathrm{\Gamma }} \right)\). It is interesting that VBM and CBM have same magnetic symmetry but show PST and spiral spin texture, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first case about the coexistence of PST and spiral spin texture in the same compound.

In Fig. 4c, d, we fix the magnetic ordering but flip the FE polarization from P to −P. The spin textures are switched according to \(\hat I{\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}\left( k \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\left( { - k} \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}\left( k \right)\). For the VBM of C-type \({\mathrm{AFM}}_y\) state, the spin at \(- k\) and \(k\) point have same orientation, i.e., \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}( - k) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\), whereas after the space inversion, one can get \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\left( { - k} \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\). Therefore, when switching the FE polarization, the PST maintains the same spin orientation (see Fig. 4c). However, as for the CBM, the spin at \(- k\) and \(k\) point have opposite orientation, i.e., \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}( - k) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\). After the space inversion, it can be \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{P}}}\left( { - k} \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{P}}(k)\). Thus, the helicity of spiral spin texture is reversed (see Fig. 4d). It is interesting about the different tunability of VBM and CBM under same external field. It is also important to note that this compound has been recently synthesized and the switching of polarization has been realized with a well-defined P–E loop44; therefore, we expect that the manipulation of spin textures by the external electric field could be easily verified by experiments. In Fig. 4e, f, we fix the FE order but flip the AFM ordering from \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{C}}\)~ y to –y to see the variation of spin texture. We find the PST of VBM (see Fig. 4e) is reversed whereas the spiral spin texture of CBM (see Fig. 4f) maintains the same helicity. The variation of spin texture is consistent with the rule of \(\hat T{\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}\left( k \right) = {\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}\left( { - k} \right) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}\left( k \right)\). For VBM, before switching L, \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}( - k) = {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\). After switching L, \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}( - k) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\). However, for CBM, before switching L, \({\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}\left( { - k} \right) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\). After switching L, \({\mathbf{S}}_{ - {\mathbf{L}}}( - k) = - {\mathbf{S}}_{\mathbf{L}}(k)\). The variation is totally different from the spin texture tunability upon the change of FE polarization. Our results demonstrate that one can manipulate the spin textures by switching the AFM order parameter but independently from the electric degrees of freedoms. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, we present a unique case in the literature, where there is coexistence of PST and spiral spin texture in the same material.

Here we show the spin textures at VBM and CBM. \({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{C}}\) ~ y (\({\mathbf{L}}_{\mathbf{C}}\) ~ −y) presents C-type AFM state with spin moment along y (−y) axis, respectively. In c and d, the polarization is reversed from p to −p. In e and f, the magnetic ordering is reversed from y to −y direction.

We also investigate the spin textures with other magnetic configurations (see Supplementary Figs 7–17). By manipulating the magnetic order parameter with different orientation and different magnetic state, the corresponding spin texture will change accordingly and it is the origin of magneto-crystalline anisotropy61. This property is dual of the spin-texture electric-anisotropy first discussed in the HOIP material (NH2CHNH2)SnI362 where it has been shown that the spin-texture topology is modified significantly upon variations of the direction of the electric polarization. The sensitivity of the topology of spin texture to variation/switching of the magnetic order parameter could have far reaching consequences in AFM spintronics, as this property could be exploited in AFM memory elements: the change in spin-texture topology of relevant electronic bands should be detectable in terms of magneto-optical Kerr effect, as already shown in the metal-organic framework material [C(NH2)3]Cr[(HCOO)3]63. Further study is in progress to verify these properties. Our results clearly suggest that one could manipulate the spin texture via tuning the magnetic ordering at different levels: by fixing the magnetic configurations but changing the L orientation in space, or by changing the different realization of L. It has been shown that AFM materials can be manipulated by applying magnetic fields36,64,65. The magnetic moments can be appreciably rotated in a quasi-static manner within the Stoner-Wohlfarth model66. In this picture, the ordered magnetic state is preserved when the magnetization is reversed and a spin-flop field can rotate the magnetic moments by 90° 67. Besides, the AFM state could be reoriented by optical excitation68,69, exchange bias70,71, strain72,73, and other different approaches36,65. We note that the manipulation of FE polarization and magnetic configuration was realized in the classical multiferroic material \({\mathrm{TbMnO}}_3\)39 and \({\mathrm{BiFeO}}_3\)40. Therefore, the FE and magnetic orderings in a polar AFM HOIP system could be tuned and the spin texture can be manipulated at the same time, thus leading to interesting magneto-optoelectronic applications.

Our study shows the possibility of tuning spin textures by electric and magnetic fields in AFM HOIP FEs and enhancing its optoelectronic performance, although there remain some challenges such as the wide bandgap and low magnetic ordering temperatures. In our TMCM-MnCl3 system, the bandgap is calculated to be 3.75 eV which is larger than the ideal bandgap suitable for optoelectronic applications. It is reported that TMCM-MnCl3 displays excellent photoluminescence properties with a near-unity photoluminescence emission efficiency44, thus our DFT calculations may overestimate the bandgap. Xiong and colleagues74,75 proposed that TMCM-MnCl3 can be further engineered through element substitution and molecular design so as to optimize for a desired physical properties, as shown by bandgap engineering. Taking the characteristic HOIP material MAPbI3 as an example, the band gap can be easily tuned from 1.2 to 3.0 eV by engineering chemical composition75. The magnetic ordering temperature can be improved as well. In our TMCM-MnCl3 system, the Néel temperature is low due to the weak interchain interaction, which can be ascribed to the large organic cation. The Néel temperature could be improved with smaller organic cation. Furthermore, the substitution on B-site magnetic ions can enhance the magnetic ordering temperature. For example, it is reported that the HOIP material ((CH3)4P)FeBr4 exhibits coupled dielectric and magnetic phase transitions above room temperature76. It is important to note that our study puts forward the concept that one can manipulate the spin texture by applying magnetic fields. The external magnetic field can stabilize the AFM ordering and raise the Néel temperature. Therefore, we hope to stimulate the search of high temperature AFM HOIP FEs in the future.

Disussion

In this work, we propose the manipulations of spin textures in the AFM HOIP FE TMCM-MnCl3. By using first-principles calculations, we identify a Rashba-like splitting in the band structure. The symmetry analyses based on magnetic space group are used to explain the band degeneracy. We find robust PST in G-type AFM state and it can be effectively manipulated by switching not only polarization but also magnetic ordering. We also find the coexistence of PST and typical spiral spin texture, depending of the relevant band electronic states, in C-type AFM state. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of coexistence of PST and spiral spin texture in the same compound. By manipulating the FE, and, interestingly, the magnetic order parameter, the spin texture can be modified significantly. Our work introduces new directions in the field of spin-texture manipulation by external fields, which goes beyond the usual electric-field control of Rashba effect in non-magnetic materials. Considering that TMCM-MnCl3 belongs to the important class of HOIPs, which is relevant to optoelectronic research, we expect that, this study could suggest new magneto-optoelectronic properties in HOIPs. As the switching of polarization in TMCM-MnCl3 has been experimentally demonstrated44, we hope to stimulate new experiments to verify manipulations of spin textures in TMCM-MnCl3 by electric and/or magnetic fields. We expect that AFM HOIP FEs have the potential to improve the optoelectronic performance and give a new strategy to design new multifunctional materials.

Methods

DFT calculations

Our first-principles calculations are performed within DFT. The interactions of valence electrons and ions is treated with the projector augmented wave method77 as implemented in the Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP)78. The exchange-correlation potential is described by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional79. The plane wave cutoff energy is fixed to be 550 eV, and all atomic positions are optimized until each component of the atomic force is smaller than 0.01 eV/Å. The \(4 \times 2 \times 4\) k-point mesh is used for the Brillouin integration. The electric polarization is calculated by using the Berry phase method50,80. In this approach, we first define a centrosymmetric reference phase which shows an AFE alignment of dipoles in the unit cell and then we continuously rotate and translate the organic cations to reach the FE phase by defining a roto-displacive path in the configuration space. In our work, we take the Van der Waals interactions into account by DFT-D3 correction method81,82 as implemented in the VASP software. The correlated nature of Mn 3d state is included by Hubbard-like corrections with repulsion energy U=3 eV and Hund coupling energy J = 1 eV. Our calculations show that small variation of U and J does not change the main results of our study. To calculate the spin textures, the mean values of the sigma matrices are evaluated at the relevant electronic states with different k-points around a reference point in the Brillouin zone.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Huang, J., Yuan, Y., Shao, Y. & Yan, Y. Understanding the physical properties of hybrid perovskites for photovoltaic applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17042 (2017).

Stranks, S. D. & Snaith, H. J. Metal-halide perovskites for photovoltaic and light-emitting devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 391–402 (2015).

McMeekin, D. P. et al. A mixed-cation lead mixed-halide perovskite absorber for tandem solar cells. Science 351, 151–155 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Chemically diverse and multifunctional hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16099 (2017).

Brenner, T. M. et al. Hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites: low-cost semiconductors with intriguing charge-transport properties. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 15007 (2016).

Wehrenfennig, C. et al. Charge-carrier dynamics in vapour-deposited films of the organolead halide perovskite CH3NH3PbI3-xClx. Energ. Environ. Sci. 7, 2269–2275 (2014).

Bi, Y. et al. Charge carrier lifetimes exceeding 15 mu s in methylammonium lead iodide single crystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 923–928 (2016).

Wehrenfennig, C. et al. High charge carrier mobilities and lifetimes in organolead trihalide perovskites. Adv. Mater. 26, 1584–1589 (2014).

Chen, T. et al. Origin of long lifetime of band-edge charge carriers in organic-inorganic lead iodide perovskites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7519–7524 (2017).

Ambrosio, F., Wiktor, J., De Angelis, F. & Pasquarello, A. Origin of low electron-hole recombination rate in metal halide perovskites. Energ. Environ. Sci. 11, 101–105 (2018).

Kirchartz, T., Markvart, T., Rau, U. & Egger, D. A. Impact of small phonon energies on the charge-carrier lifetimes in metal-halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 939–946 (2018).

Zheng, F., Tan, L. Z., Liu, S. & Rappe, A. M. Rashba spin-orbit coupling enhanced carrier fifetime in CH3NH3PbI3. Nano Lett. 15, 7794–7800 (2015).

Etienne, T., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Dynamical origin of the Rashba effect in organohalide lead perovskites: a key to suppressed carrier recombination in perovskite solar cells? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1638–1645 (2016).

Niesner, D. et al. Structural fluctuations cause spin-split states in tetragonal CH3NH3PbI3 as evidenced by the circular photogalvanic effect. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9509–9514 (2018).

Niesner, D. et al. Giant Rashba splitting in CH3NH3PbBr3 organic-inorganic perovskite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 126401 (2016).

Manchon, A. et al. New perspectives for Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Nat. Mater. 14, 871–882 (2015).

Zhang, X. et al. Hidden spin polarization in inversion-symmetric bulk crystals. Nat. Phys. 10, 387–393 (2014).

Rashba, E. I. Properties of semiconductors with an extremum loop. 1. cyclotron and combinational resonance in a magnetic field perpendicular to the plane of the loop. Sov. Phys. Solid State 2, 1109–1122 (1960).

Dresselhaus, G., Kip, A. F. & Kittel, C. Spin-orbit interaction and the effective masses of holes in germanium. Phys. Rev. 95, 568–569 (1954).

Krempasky, J. et al. Entanglement and manipulation of the magnetic and spin-orbit order in multiferroic Rashba semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 7, 13071 (2016).

Krempasky, J. et al. Operando imaging of all-electric spin texture manipulation in ferroelectric and multiferroic Rashba semiconductors. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021067 (2018).

Rinaldi, C. et al. Ferroelectric control of the spin texture in GeTe. Nano Lett. 18, 2751–2758 (2018).

Di Sante, D., Barone, P., Bertacco, R. & Picozzi, S. Electric control of the giant Rashba effect in bulk GeTe. Adv. Mater. 25, 509–513 (2013).

Kim, M. et al. Switchable S=1/2 and J=1/2 Rashba bands in ferroelectric halide perovskites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6900–6904 (2014).

Kepenekian, M. et al. Rashba and Dresselhaus effects in hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites: from basics to devices. ACS Nano 9, 11557–11567 (2015).

Zhai, Y. X. et al. Giant Rashba splitting in 2D organic-inorganic halide perovskites measured by transient spectroscopies. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700704 (2017).

Leppert, L., Reyes-Lillo, S. E. & Neaton, J. B. Electric field- and strain-induced Rashba effect in hybrid halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 3683–3689 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. Circular photogalvanic spectroscopy of Rashba splitting in 2D hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite multiple quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 11, 323–323 (2020).

Yamauchi, K. et al. Coupling ferroelectricity with spin-valley physics in oxide-based Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 037602 (2015).

Lutz, P. et al. Large spin splitting and interfacial states in a Bi/BaTiO3(001) Rashba ferroelectric heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 044011 (2017).

Tao, L. L. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Persistent spin texture enforced by symmetry. Nat. Commun. 9, 2763 (2018).

He, J. et al. Tunable metal-insulator transition, Rashba effect and Weyl Fermions in a relativistic charge-ordered ferroelectric oxide. Nat. Commun. 9, 492 (2018).

Varignon, J., Santamaria, J. & Bibes, M. Electrically switchable and tunable Rashba-type spin splitting in covalent perovskite oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 116401 (2019).

Djani, H. et al. Rationalizing and engineering Rashba spin-splitting in ferroelectric oxides. npj Quant. Mater. 4, 51 (2019).

Jungwirth, T., Marti, X., Wadley, P. & Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 231–241 (2016).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Lebrun, R. et al. Tunable long-distance spin transport in a crystalline antiferromagnetic iron oxide. Nature 561, 222–225 (2018).

Cheong, S.-W. & Mostovoy, M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13–20 (2007).

Kimura, T. et al. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 426, 55–58 (2003).

Wang, J. et al. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science 299, 1719–1722 (2003).

Clune, A. J. et al. Magnetic field-temperature phase diagram of multiferroic (NH4)2FeCl5 center dot H2O. npj Quant. Mater. 4, 44 (2019).

Ping, Y. & Zhang, J. Z. Spin-optotronic properties of organometal halide perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 6103–6111 (2018).

Liao, K. et al. Spintronics of hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites: miraculous basis of integrated optoelectronic devices. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 15 (2019).

You, Y.-M. et al. An organic-inorganic perovskite ferroelectric with large piezoelectric response. Science 357, 306–309 (2017).

Schliemann, J. Colloquium: persistent spin textures in semiconductor nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 011001 (2017).

Bernevig, B. A., Orenstein, J. & Zhang, S.-C. Exact SU(2) symmetry and persistent spin helix in a spin-orbit coupled system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 236601 (2006).

Altmann, P. et al. Suppressed decay of a laterally confined persistent spin helix. Phys. Rev. B 90, 201306(R) (2014).

Tang, Y.-Y. et al. Multiaxial molecular ferroelectric thin films bring light to practical applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 8051–8059 (2018).

Kingsmith, R. D. & Vanderbilt, D. Theory of polarization of crystalline solids. Phys. Rev. B 47, 1651–1654 (1993).

Resta, R. Macroscopic polarization in crystalline dielectric: the geometric phase approach. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 899–915 (1994).

Li, P.-F. et al. Organic enantiomeric high-T-c ferroelectrics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5878–5885 (2019).

Liu, J.-C. et al. A molecular thermochromic ferroelectric. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 3495–3499 (2020).

Li, P.-F. et al. Unprecedented ferroelectric-antiferroelectric-paraelectric phase transitions discovered in an organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8752–8757 (2017).

Campbell, B. J. et al. ISODISPLACE: a web-based tool for exploring structural distortions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 39, 607–614 (2006).

Goodenough, J. B. Theory of the role of covalence in the perovskite-type manganites [La,M(II)] MnO3. Phys. Rev. 100, 564–573 (1955).

Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 10, 87–98 (1959).

Xiang, H. J. et al. Predicting the spin-lattice order of frustrated systems from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 84, 224429 (2011).

Xiang, H. et al. Magnetic properties and energy-mapping analysis. Dalton Trans. 42, 823–853 (2013).

Hu, S. et al. Dipole order in halide perovskites: polarization and Rashba band splittings. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 23045–23054 (2017).

Yuan, L. et al. Giant momentum-dependent spin splitting in symmetric low Z antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 102, 014422 (2020).

Strange, P., Staunton, J. B., Gyorffy, B. L. & Ebert, H. First principles theory of magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Phys. B 172, 51–59 (1991).

Stroppa, A. et al. Tunable ferroelectric polarization and its interplay with spin-orbit coupling in tin iodide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 5, 5900 (2014).

Fan, F. R. et al. Electric-magneto-optical Kerr effect in a hybrid organic-inorganic perovskite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12883–12886 (2017).

Jacobs, I. S. & Lawrence, P. E. Metamagnetic phase transitions and hysteresis in FeCl2. Phys. Rev. 164, 866 (1967).

Song, C. et al. How to manipulate magnetic states of antiferromagnets. Nanotechnology 29, 112001 (2018).

Stoner, E. C. & Wohlfarth, E. P. A mechanism of magnetic hysteresis in heterogeneous alloys. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 240, 599–642 (1948).

Jacobs, I. S. Spin-flopping in MnF2 by high magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 32, S61 (1961).

Kimel, A. V. et al. Laser-induced ultrafast spin reorientation in the antiferromagnet TmFeO3. Nature 429, 850–853 (2004).

Kimel, A. V. et al. Inertia-driven spin switching in antiferromagnets. Nat. Phys. 5, 727–731 (2009).

Dieny, B. et al. Giant magnetoresistance in soft ferromagnetic multiplayers. Phys. Rev. B 43, 1297–1300 (1991).

Scholl, A. et al. Creation of an antiferromagnetic exchange spring. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 247201 (2004).

Chen, X. Z. et al. Tunneling anisotropic magnetoresistance driven by magnetic phase transition. Nat. Commun. 8, 449 (2017).

Lee, J. H. & Rabe, K. M. Epitaxial-strain-induced multiferroicity in SrMnO3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 207204 (2010).

Ye, H.-Y. et al. Bandgap engineering of lead-halide perovskite-type ferroelectrics. Adv. Mater. 28, 2579–2586 (2016).

Unger, E. L. et al. Roadmap and roadblocks for the band gap tunability of metal halide perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 11401–11409 (2017).

Shi, P.-P. et al. Novel phase-transition materials coupled with switchable dielectric, magnetic, and optical properties: (CH3)4PFeCl4 and (CH3)4PFeBr4. Chem. Mater. 26, 6042–6049 (2014).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Vanderbilt, D. & Kingsmith, R. D. Electric polarization as a bulk quantity and its relation to surface-charge. Phys. Rev. B 48, 4442–4455 (1993).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154101 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by NSFC 11825403, the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar), the Qing Nian Ba Jian Program, and the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation. F. L. thanks Dr. K. Liu and J. Li for useful discussion. T.G. thanks the kind hospitality of CNR-SPIN c/o Department of Chemical and Physical Science of University of L’Aquila where this project was initiated during the visiting period from 8 November 2017 to 14 January 2018. A.S. thanks the warm hospitality of W.Li, X.-H. Bu (Nankai University), H. Wu (Fudan University), and W. Ren (Shanghai University), where this work was partially finalized.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X. and A.S. proposed and supervised the project. F.L. and T.G. performed the first-principles calculations with the help from J.J. and J.F. F.L., T.G., and J.J. prepared the initial draft of the paper. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the paper. F.L. and T.G. contribute equally to this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lou, F., Gu, T., Ji, J. et al. Tunable spin textures in polar antiferromagnetic hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites by electric and magnetic fields. npj Comput Mater 6, 114 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00374-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00374-8

This article is cited by

-

Giant room temperature elastocaloric effect in metal-free thin-film perovskites

npj Computational Materials (2021)