Abstract

In spinful electronic systems, time-reversal symmetry makes that all Kramers pairs at the time-reversal-invariant momenta are Weyl points (WPs) in chiral crystals. Here, we find that such symmetry-enforced WPs can also emerge in bosonic systems (e.g. phonons and photons) due to nonsymmorphic symmetries. We demonstrate that for some nonsymmorphic chiral space groups, several high-symmetry k-points can host only WPs in the phononic systems, dubbed symmetry-enforced Weyl phonons (SEWPs). The SEWPs, enumerated in Table 1, are pinned at the boundary of the three-dimensional (3D) Brillouin zone (BZ) and protected by nonsymmorphic crystal symmetries. By performing first-principles calculations and symmetry analysis, we propose that as an example of SEWPs, the twofold degeneracies at P are monopole WPs in K2Sn2O3 with space group 199. The two WPs of the same chirality at two nonequivalent P points are related by time-reversal symmetry. In particular, at ~17.5 THz, a spin-1 Weyl phonon is also found at H, since two Weyl phonons at P carrying a non-zero net Chern number cannot exist alone in the 3D BZ. The significant separation between P and H points makes the surface arcs long and clearly visible. Our findings not only present an effective way to search for WPs in bosonic systems, but also offer some promising candidates for studying monopole Weyl and spin-1 Weyl phonons in realistic materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological phonons1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, referring to the quantized excited vibrational states of interacting atoms, have most recently attracted attention in condensed matter physics because of their unique physical nature8,9,10,11,12,13. In similarity to various quasiparticles in electronic systems, topological phonons, such as (spin-1/2 or monopole) Weyl, Dirac, spin-1 Weyl, and charge-2 Dirac phonons, have been predicted/observed in 3D momentum space of solid crystals14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, strengthening largely our understanding of elementary particles in the universe. For instance, Zhang et al.22 predicted that both spin-1 Weyl phonons and charge-2 Dirac phonons exist in the CoSi system. The coexistence of the above two different classes of topological phononic quasiparticles exhibits exotic topologically nontrivial features, such as noncontractible surface arcs and double-helicoid surface states23. Moreover, phonons can be excited to all energy space to generate unusual transport behaviors, since they are not limited by Pauli exclusion principle and Fermi surfaces in materials. The phononic systems with these particular properties provide a good platform for studying topological bosonic states in experiments.

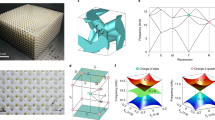

According to Nielsen-Ninomiya no-go theorem24, WPs always come in pairs with opposite chirality, acting as sources/sinks of Berry curvature in the 3D BZ25. The WPs are formed by two bands with linear dispersions in 3D momentum space, which have Chern numbers (C) of ±1 and robust against small perturbations. They are usually not easy to be predicted due to the lack of symmetry protections, and the predictions of WPs usually require comprehensive numerical calculations in the 3D BZ26. However, in the spinful electronic systems, Kramers pairs at the time-reversal-invariant momenta are enforced to be WPs by time-reversal (TR) symmetry in chiral crystals (Fig. 1a), where there are no improper rotation symmetries, such as inversion or mirror15,16. In this work, by checking the symmetries of 230 space groups (SGs), we have uncovered that symmetry-enforced WPs can also emerge in bosonic systems, such as phonons (mainly discussed in the work), photons, and so on, due to the presence of nonsymmorphic symmetries (Fig. 1b, c). These WPs are all pinned at the high-symmetry k-points on the boundary of the 3D BZ. Unlike the TR-enforced WPs in spinful electronic systems15, where the WPs are usually buried in bulk states due to the weak strength of spin−orbit coupling, the nonsymmorphic-crystal-symmetry-enforced Weyl phonons can be well exposed. Consequently, the associated surface arcs are long and robust, which can be easily probed in future experiments. By performing symmetry analysis in 230 SGs in the presence of TR symmetry, we have demonstrated that for some chiral SGs, several high-symmetry k-points can host only WPs in the phononic systems, dubbed symmetry-enforced Weyl phonons (SEWPs). We enumerate all the SEWPs at the high-symmetry k-points of the SGs in Table 1. In this table, all the phonon bands are doubly degenerate at those high-symmetry k-points and each twofold degeneracy represents a WP. Thus, one can easily predict WPs in such systems as long as the materials are of the SGs in Table 1. The results significantly lower the difficulty to predict the WPs in bosonic systems.

As we know, a WP can be stabilized at a general point in the 3D BZ without any symmetries. However, an additional symmetry can pin the WP at a fixed point. a In a spinful system of a chiral crystal, all the Kramers degeneracies at the time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) are representing WPs. In a spinless system of a chiral crystal, the twofold degeneracies can also be enforced to form WPs, by some nonsymmorphic crystal (unitary) symmetries in b or by the combined (antiunitary) symmetry of TR symmetry and a fourfold screw symmetry 41 in c.

By employing first-principles calculations, we predicted that as an example of the SEWPs, twofold degeneracies at the P point are WPs in the crystal of K2Sn2O3 in SG 199. First, there are two nonequivalent P points in the first BZ, which are related by time-reversal symmetry. Therefore, the WPs at two P points host the same chirality. Second, at ~17.5 THz, a spin-1 Weyl phonon is also found at H, since two Weyl phonons at P carrying a non-zero net Chern number cannot exist alone in the 3D BZ. Third, the spin-1 Weyl phonon here has been found to locate on the boundary of the BZ, which is robust against the LOTO (longitudinal and transverse optical phonon splitting) modification in the phonon spectrum. Lastly, the symmetry-related WPs host the same chiral charge, giving rise to nontrivial isofrequency surfaces of phonons, associated with non-zero Chern numbers. In addition, the long surface arcs and the double-helicoid states are presented as well. More examples of SEWPs can be found in the Supplementary Information. These new findings not only provide an effective way to search for monopole WPs in bosonic systems, but also predict some promising candidates for studying topological quasiparticles in experiments.

Results

Searching for SEWPs by symmetry analysis

The guiding principle of our search is to find two-dimensional irreducible representations (irreps) of the (little) group of lattice symmetries at high-symmetry k-points in the 3D BZ for each of the 230 SGs in the presence of TR symmetry; the dimension of the irreps corresponds to the number of bands that meet at the high-symmetry k-points. Then, one has to exclude the SGs that contain improper rotational symmetries or twofold screw symmetries (\({\bar{C}}_{2}\)) with \({[{\bar{C}}_{2}{\mathcal{T}}]}^{2}=-1\), to make sure that there is no double degeneracy along any high-symmetry line/plane crossing these k-points. Since we are interested in bosonic systems, we consider only the single-valued representations; TR symmetry is an antiunitary that squares to 1 (i.e., \({[{\mathcal{T}}]}^{2}=1\)). We find that the twofold WPs pinned at high-symmetry k-points in bosonic systems can have Chern numbers of ±1 [i.e. (monopole) WPs], ±2 [i.e., double WPs] and ±4 [i.e., quadruple WPs], respectively. The (monopole) WPs are formed by two bands with linear dispersions27 and can be stabilized at general points in 3D momentum space, while two bands of the double and quadruple WPs have nonlinear dispersions27,28,29,30,31,32,33, which are usually pinned at high-symmetry k-points by symmetries. A complete list of the high-symmetry k-points, where these three kinds of twofold WPs can be pinned and protected in bosonic systems, is presented in Table 1 in Section A of the Supplementary Information. For most of them, besides the two-dimensional irreps, one-dimensional and/or three-dimensional irreps are also allowed. However, at several specific k-points, only the two-dimensional irrep of WPs is allowed in the phononic systems, dubbed SEWPs, which are mainly focused on in this work.

The results of SEWPs are summarized in Table 1. These SEWPs are monopole WPs and are located on the boundary of the 3D BZ. All of them are chiral SGs with nonsymmorphic symmetries, and all representations are projective; these are in fact necessary ingredients for the (spin-1/2) Weyl excitations in the phononic systems. We find that most of twofold degeneracies are protected by the anticommutation relation of two unitary operators (i.e., {A, B} = 0) in Table 1, except for SG 80. At the P point of SG 80, an antiunitary symmetry of its little group is the combined operator of time reversal (\({\mathcal{T}}\)) and fourfold screw symmetry (\({{\bf{4}}}_{1}\equiv \{{C}_{4z}| \frac{3}{4}\frac{1}{4}\frac{1}{2}\}\)) (see the definition in ref. 34. One can check that \({({\mathcal{T}}\cdot {{\bf{4}}}_{1})}^{4}=\{E| 110\}={e}^{2i\pi (\frac{1}{4}+\frac{1}{4})}=-1\), which enforces a Kramers-like degeneracy as discussed in ref. 35.

Then, we take SG 199 as an example to illustrate the anticommutation relation in the main text (see more derivations for all other SGs in Table 1 in Section D of the Supplementary Materials). SG 199 hosts only Weyl phonons at the P point (the high-symmetry points are defined in ref. 34), even though it hosts three different irreps of the AG \({G}_{48}^{3}\) in Table 1. This SG has a body-centered cubic Bravais lattice. The operators C2x and C2z acting on the primitive lattice vectors (t1, t2, t3) are presented34 as follows:

Thus,

At the P point (\(\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{4},\frac{1}{4}\)), the pure translation operator {E∣3, 2, 1} is expressed as e2iπ(3+2+1)/4 = −1. Therefore, we get {A, B} = 0, which yields all the phonon bands to be at least twofold degenerate at the P point. Note that no higher n-dimensional irreps (n > 2) are found at P. In addition, we have checked that there is no symmetry-protected degeneracy on the high-symmetry planes/lines crossing the P point.

Effective k ⋅ p models

Let us consider a two-band model at the P point in SG 199 first. We have A2 = {E∣000} = 1, B2 = {E∣220} = 1 with E the identity operator and {A, B} = 0. With the matrix representations of A = σx and B = σz, the k ⋅ p invariant Hamiltonian is derived as (to the first order),

with σx,y,z Pauli matrices, kx,y,z momentum offset from P point, and v1,2,3 real coefficients. Obviously, it is a Weyl Hamiltonian. Other SGs in Table 1 with antiunitary commutation relations share the similar results. We notice that the P point is a TR noninvariant point at a corner of the BZ (i.e., P ≠ −P). Those systems host another Weyl phonon of the same chirality at −P due to TR symmetry, indicating that there must be some other nontrivial excitation(s) in the systems, since the two Weyl phonons carrying a non-zero net Chern number cannot exist alone in the 3D BZ. Here, we choose K2Sn2O3 in SG 199 as an example for illustration, which exhibits a spin-1 Weyl phonon (C = 2) at H and two Weyl phonons (C = −1) at P between the 39th and 40th bands.

Then we consider the P point in SG 80, where we cannot find two symmetry operators with the anticommutation relation. We consider two symmetry operators at P point: \(D=\{{C}_{2z}| 100\}={{\bf{4}}}_{1}^{2}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\cdot {{\bf{4}}}_{1}\), where 41 is a nonsymmorphic fourfold rotational symmetry, followed by a fractional lattice translation [T(\(\overrightarrow{c}\)/4), where \(\overrightarrow{c}\) is a lattice constant in the z direction]. It is worth noting that 41 is not a symmetry operator that keeps P invariant (see more details in the Supplementary Information). We can express the two operators as D = −iσz and \({\mathcal{T}}\cdot {{\bf{4}}}_{1}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({\sigma }_{x}+{\sigma }_{y}){\mathcal{K}}\), which meet the conditions: \({({\mathcal{T}}\cdot {{\bf{4}}}_{1})}^{2}=D\) and \({({\mathcal{T}}\cdot {{\bf{4}}}_{1})}^{4}=-1\). Thus, the k ⋅ p invariant Hamiltonian is derived as (to the first order of k),

with \(\theta =\frac{{v}_{2}}{{v}_{1}}\), \({k}_{| | }=\frac{{k}_{x}\,+\,\theta {k}_{y}}{\sqrt{1\,+\,{\theta }^{2}}}\) and \({k}_{\perp }=\frac{\theta {k}_{x}\,-\,{k}_{y}}{\sqrt{1\,+\,{\theta }^{2}}}\). It is also a Weyl Hamiltonian with isotropy in the kx−ky plane.

SEWPs in realistic materials

Based on our symmetry analysis, the phonon dispersions of any material in the SGs in Table 1 have to contain WPs at those high-symmetry points. To confirm the theoretical results, we have systematically performed the ab initio phonon calculations on some materials for each SG in Table 1. As an example, we focus on the results and discussions on K2Sn2O3 of SG 199 in the main text, and put the discussions for other SGs in the Supplementary Information. The crystallographic data of K2Sn2O3 are adopted from ref. 36, and the primitive cell is illustrated in Fig. 2a, where the purple (black and red) atoms stand for K (Sn and O) atoms. The material example belongs to the body-centered cubic structure with SG I213. Each primitive cell contains 14 atoms with four K, and four Sn and six O atoms. The bulk BZ, (001) surface BZ and (110) surface BZs are shown in Fig. 2b.

a Crystal structure of K2Sn2O3 in a primitive cell, where the purple (black and red) atoms stand for K (Sn and O). b The bulk BZ of the sample and the related (001) and (110) surface BZs. c, d The phonon dispersions of K2Sn2O3 along high-symmetry lines and the density of states (DOS) without the polariton of LOTO splitting. The Chern numbers of some nontrivial phonon branches around P and H points are shown. e The distributions of two monopole WPs (P1 and P2 points) and the spin-1 WP (H point) in the first BZ. f, g The evolutions of Wannier centers of the 39th phonon band for H, P1 and P2. The Wannier centers (φ) are defined on the series of Wilson loops (parameterized by θ) over a sphere enclosing a WP (inset in g). h The distribution of the Berry curvature in the (\(1\bar{1}0\)) plane. The H point (“o”) and the P1/P2 point (“x”) are viewed as the source and the sink of Berry curvature, respectively.

The calculated phonon dispersions of K2Sn2O3 are shown in Fig. 2c. It is clearly seen that there are some band crossings (degeneracies) at high-symmetry k-points, especially for the optical dispersions. First, we do find that all the phonon bands are doubly degenerate at P point, resembling monopole WPs. The corresponding results of the Chern number calculations for the bands around P point are shown in Fig. 2c and its insets. From the dispersions in Fig. 2c, we turn our attention to the WPs formed by the 39th and 40th bands, which have linear dispersions in a wide frequency range. Second, we have also computed the Chern numbers of the two nonequivalent P points (i.e., P1 and P2). The chiral charges of WPs at P1 and P2 are computed to be −1. Here, the chiral charge of a WP is defined by the Chern number of the lower band, which is computed by the Wilson loop technique on a sphere enclosing the WP37,38. The results of the sphere for the 39th band around the P point are shown in Fig. 2g. It is consistent with TR symmetry in the system, as mentioned before. By fitting the two phonon bands in the vicinity of P point, the v1, v2 and v3 coefficients in Eq. (3) are given as 2.19, 2.19 and −2.19 THz ⋅ Å. Third, since two Weyl phonons carrying a non-zero net Chern number cannot exist alone in the 3D BZ, a threefold spin-1 Weyl phonon is found at H point (highlighted by blue color), formed by the 39th, 40th, and 41st bands. The Chern numbers of these three bands are computed to be +2, 0, −2, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2c. The results of the sphere for the 39th band around the H point are shown in Fig. 2f. As illustrated in Fig. 2h, the spin-1 WP with C = +2 at H point acts as the “source” point, whereas two monopole WPs with C = −1 at P points can be viewed as the “sink” points of the Berry curvature.

Consequently, this system hosts several unconventional properties: (i) The symmetry-related WPs are of the same chirality, i.e., the monopole WPs at the P points, which can generate the nontrivial isofrequency surfaces of photon with non-zero Chern numbers. (ii) The nontrivial excitations (quasiparticles) are pinned at the high-symmetry k-points, such as the monopole Weyl phonons at P and the threefold spin-1 Weyl phonon at H, which give rise to large surface arcs due to the large separation of the sources and sinks of the Berry curvature. (iii) The spin-1 Weyl phonon is proposed on the boundary of the BZ of a realistic material and is robust against the LOTO modification (see Supplementary Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information), supporting that it could be observed in future experiments. Such a spin-1 Weyl phonon at H is also found in K8 carbon of SG 214 in Section D of the Supplementary Information.

Exotic surface states

Then, we turn to examine the isofrequency surface contours and the surface arcs to explore the exotic physical behaviors of the SEWPs. As the two P points are projected to the BZ corner (\(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\)) and the H point to the BZ center (\(\widetilde{\Gamma }\)) in Fig. 3a, we plot the (001)-surface phonon dispersions along the green line of Fig. 3a (i.e., \(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\)-\(\widetilde{\Gamma }\)-\(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\)) in Fig. 3b. At two chosen frequencies of 16.58 (i.e., the frequency of the WPs at P) and 16.73 THz, the arc-like surface states are illustrated in Fig. 3a, c, respectively. The surface arcs connect the two monopole WPs at \(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\) and one spin-1 Weyl phonon at \(\widetilde{\Gamma }\). As expected, the isofrequency surface contours display double-helicoid states39, which are spiral clockwise with increasing frequency. The surface phonon dispersions along the square-shaped path around \(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\) show double-helicoid surface states (see Fig. 3d), which verifies further the topological nontrivial feature of the two monopole WPs at P points.

a, c Isofrequency surface contours at two frequencies, 16.58 and 16.73 THz. b The surface phonon dispersions along \(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\)-\(\widetilde{\Gamma }\)-\(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\). The two frequencies are indicated by two horizontal lines in b. d The surface phonon dispersions along the square path around the \(\widetilde{{\rm{M}}}\) point in a, which demonstrate the double-helical surface states.

Next, we plot the (110)-surface phonon dispersions in Fig. 4a and the isofrequency surface contours in Fig. 4b−d. On the (110)-surface BZ (Fig. 4b), the H, P1 and P2 points are projected to \(\overline{{\rm{H}}}\), \(\overline{{\rm{P}}}1\) and \(\overline{{\rm{P}}}2\), respectively. The evolution of the surface arcs is illustrated by isofrequency surface contours for three frequencies, in which the surfaces arcs are clearly visualized. In this frequency range, a Lifshitz transition occurs clearly in the arc-like surface states. Moreover, the surfaces arcs at higher frequencies are presented in Supplementary Fig. S2 of the Supplementary Information.

a The surface phonon dispersions along the vertical line (i.e., \(\overline{{\rm{H}}}\)-\(\overline{P}1\)-\(\overline{\Gamma }\)-\(\overline{P}2\)-\(\overline{{\rm{H}}}\)) on the (110)-surface BZ of Fig. 1b. b−d The isofrequency surface contours at three frequencies, 16.58, 16.62 and 16.73 THz as indicated by the three horizontal lines in a. One can find that Lifshitz transition occurs in the surface arc states in the evolution.

Discussion

By performing symmetry analysis in 230 SGs in the presence of TR symmetry, we demonstrate that there are also symmetry-enforced WPs in the bosonic systems, e.g. phonons. We have given a complete list of high-symmetry k-points, where twofold Weyl nodes (e.g. C = ±1, ±2, and ±4) are protected. This list can guide future experiments in the study of various WPs. Among them, several k-points can support only twofold Weyl phonons, dubbed SEWPs. Such SEWPs have Chern numbers of ±1 and appear in the nonsymmorphic chiral crystals due to the lack of improper rotation symmetries and the presence of nonsymmorphic symmetries. We summarize the high-symmetry k-points of SEWPs in Table 1. The SEWPs are pinned at the boundary of the 3D BZ by nonsymmorphic symmetries, or the combined symmetry of TR and 41. To confirm our findings, we have systematically investigated the phonon spectra of some realistic materials of the SGs in Table 1 by using first-principles calculations. Taking K2Sn2O3 of SG 199 as an example, two Weyl phonons at P and a spin-1 Weyl phonon at H appear together in between the 39th and 40th bands. The corresponding surface phonon dispersions display multiple double-helicoid surface states. In addition, the significant separation between the points P and H forms very long and visible surface arcs. Our findings not only present an effective way to search for WPs in bosonic systems, but also offer some promising candidates for studying monopole Weyl and spin-1 Weyl phonons.

Methods

We carried out the density functional theory calculations using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package40,41,42 with the generalized gradient approximation in the form of Pardew−Burke−Ernzerhof function for the exchange-correlation potential43,44,45. An accurate optimization of structural parameters is employed by minimizing the interionic forces below 10−6 eV/Å and an energy cutoff at 520 eV. The BZ is gridded with 3 × 3 × 3 k-points. Then the phonon dispersions are gained using the density functional perturbation theory, implemented in the Phonopy Package46. The force constants are calculated using a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell. To reveal the phonon topological nature, we constructed the phononic Hamiltonian of the tight-binding (TB) model and obtained the surface local density of states with the open-source software Wanniertools47 code and surface Green’s functions48. The irreps of the phonon bands can be computed by the program—ir2tb—on the phononic Hamiltonian of the TB model49. Wilson loop method37,38 is used to find the Chern numbers or topological charge of monopole WPs and spin-1 WPs.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The related codes are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Kane, C. L. & Lubensky, T. C. Topological boundary modes in isostatic lattices. Nat. Phys. 10, 39 (2014).

Prodan, C. & Prodan, E. Topological phonon modes and their role in dynamic instability of microtubules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 248101 (2009).

Zhang, L. F., Ren, J., Wang, J. S. & Li, B. W. Topological nature of the phonon Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 105, 225901 (2010).

Liu, Y. X., Xu, Y., Zhang, S. C. & Duan, W. H. Model for topological phononics and phonon diode. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064106 (2017).

Chen, B.G.-g., Upadhyaya, N. & Vitelli, V. Nonlinear conduction via solitons in a topological mechanical insulator. Proc. Nalt. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13004–13009 (2014).

Wang, P., Lu, L. & Bertoldi, K. Topological phononic crystals with one-way elastic edge waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 104302 (2015).

Susstrunk, R. & Huber, S. D. Observation of phononic helical edge states in a mechaniscal topological insulator. Science 349, 47 (2015).

Mousavi, S. H., Khanikaev, A. B. & Wang, Z. Topologically protected elastic waves in phononic metamaterils. Nat. Commun. 6, 8682 (2015).

He, C. et al. Acoustic topological insulator and robust one-way sound transport. Nat. Phys. 12, 1124 (2016).

Lu, L., Fu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Weyl points and line nodes in gyroid photonic crystals. Nat. Photon. 7, 294 (2013).

Lu, L. et al. Experimental observation of Weyl points. Science 349, 622 (2015).

Zhang, L. F. & Niu, Q. Chiral phonons at high-symmetry points in monolayer hexagonal lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 115502 (2015).

Gao, M., Zhang, W. & Zhang, L. Nondegenerate chiral phonons in graphene/hexagonal boron nitride heterostructure from first-principles calculations. Nano Lett. 18, 4424 (2018).

Stenull, O., Kane, C. L. & Lubensky, T. C. Topological phonons and Weyl lines in three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 068001 (2016).

Chang, G. et al. Topological quantum properties of chiral crystals. Nat. Mater. 17, 978 (2018).

Chang, G. et al. Unconventional chiral fermions and large topological Fermi arcs in RhSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 206401 (2017).

Liu, Q. B., Fu, H. H., Xu, G., Yu, R. & Wu, R. The categories of phononic topological Weyl open nodal lines and a potential material candidate: Rb2Sn2O3. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 4045 (2019).

Xie, B., Liu, H., Cheng, H., Liu, Z., Chen, S. & Tian, J. Experimental realization of type-II Weyl points and Fermi arcs in phononic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 104302 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Topological triply degenerate point with double Fermi arcs. Nat. Phys. 15, 645 (2019).

Xia, B. W., Wang, R., Chen, Z. J., Zhao, Y. J. & Xu, H. Symmetry-protected ideal type-II Weyl phonons in CdTe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 065501 (2019).

Li, F., Huang, X., Lu, J., Ma, J. & Liu, Z. Weyl points and Fermi arcs in a chiral phononic crystal. Nat. Phys. 14, 30 (2018).

Zhang, T. T. et al. Double-Weyl phonons in transition-metal monosilicides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 016401 (2018).

Miao, H. et al. Observation of double Weyl phonons in parity-breaking FeSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 035302 (2018).

Nielsen, H. B. & Ninomiya, M. Absence of neutrinos on a lattice. I. Proof by homotopy theory. Nucl. Phys. B 185, 20 (1981).

Xie, Q. et al. Phononic Weyl points and one-way topologically protected nontrivial in noncentrosymmetric WC-type materials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 174306 (2019).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Wang, R. et al. Symmetry-protected topological triangular Weyl complex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 105303 (2020).

He, H. et al. Observation of quadratic Weyl points and double-helicoid arcs. Nat. Commun. 11, 1820 (2020).

He, H. et al. Topological negative refraction of surface acoustic waves in a Weyl phononic crystal. Nature 560, 61 (2018).

Shi, W. et al. A charge-density-wave Weyl semimetal. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.04037 (2019).

Li, X. P. et al. Type-III Weyl semimetals and its materialization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.12178 (2019).

Zhang, T., Takahashi, R., Fang, C. & Murakami, S. Twofold quadruple Weyl nodes in chiral cubic crystals. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.02562 (2020).

Liu, Q. B. et al. Twofold Weyl nodes with topological charges of ±4 (work in progress).

Bradley, C. J. & Cracknell, A. P. The Mathematical Theory of Symmetry in Solids (Oxford University Press, 1972).

Schindler, F. et al. Higher-order topological insulators. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat0346 (2018).

Geoffroy, H., Chris, F., Virginie, E., Anubhav, J. & Gerbrand, C. Data mined ionic substitutions for the discovery of new compounds. Inorg. Chem. 50, 656 (2011).

Soluyanov, A. A. & Vanderbilt, D. Computing topological invariants without inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 83, 235401 (2011).

Yu, R., Qi, X. L., Bernevig, A., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Equivalent expression of \(Z_2\) topological invariant for band insulators using the non-Abelian Berry connection. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075119 (2011).

Fang, C., Lu, L., Liu, J. & Fu, L. Topological semimetals with helicoid surface states. Nat. Phys. 12, 936 (2016).

Kresse, G. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 222, 192–193 (1995).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. B 140, A1133 (1965).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Mater. 108, 1 (2015).

Wu, Q. S., Zhang, S. N., Song, H. F., Troyer, M. & Soluyanov, A. A. WannierTools: an open-source software package for novel topological materials. Comp. Phys. Commun. 224, 405 (2018).

Sancho, M. P. L., Sancho, J. M. L., Sancho, J. M. L. & Rubio, J. Highly convergent schemes for the calculation of bulk and surface Green functions. J. Phys. F: Metal. Phys. 15, 851 (1985).

Gao, J., Wu, Q., Persson, C. & Wang, Z. Irvsp: to obtain irreducible representations of electronic states in the VASP. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.04032 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11774104, 11504117, and 11274128) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB33000000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and H.-H.F. conceived and supervised the project. Q.-B.L. and H.-H.F. did the phonon calculations. Y.Q. and Z.W. did the symmetry analysis. All authors contributed to analyzing the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, QB., Qian, Y., Fu, HH. et al. Symmetry-enforced Weyl phonons. npj Comput Mater 6, 95 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00358-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-020-00358-8

This article is cited by

-

Structural, elastic, mechanical, electronic, and optical properties of cubic K2Pb2O3 from first-principle study

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2024)

-

Symmetry-enforced nodal chain phonons

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

A charge-density-wave topological semimetal

Nature Physics (2021)

-

Degenerate topological line surface phonons in quasi-1D double helix crystal SnIP

npj Computational Materials (2021)

-

Topological materials discovery from crystal symmetry

Nature Reviews Materials (2021)