Abstract

An emerging chalcogenide perovskite, CaZrSe3, holds promise for energy conversion applications given its notable optical and electrical properties. However, knowledge of its thermal properties is extremely important, e.g. for potential thermoelectric applications, and has not been previously reported in detail. In this work, we examine and explain the lattice thermal transport mechanisms in CaZrSe3 using density functional theory and Boltzmann transport calculations. We find the mean relaxation time to be extremely short corroborating an enhanced phonon–phonon scattering that annihilates phonon modes, and lowers thermal conductivity. In addition, strong anharmonicity in the perovskite crystal represented by the Grüneisen parameter predictions, and low phonon number density for the acoustic modes, results in the lattice thermal conductivity to be limited to 1.17 W m−1 K−1. The average phonon mean free path in the bulk CaZrSe3 sample (N → ∞) is 138.1 nm and nanostructuring CaZrSe3 sample to ~10 nm diminishes the thermal conductivity to 0.23 W m−1 K−1. We also find that p-type doping yields higher predictions of thermoelectric figure of merit than n-type doping, and values of ZT ~0.95–1 are found for hole concentrations in the range 1016–1017 cm−3 and temperature between 600 and 700 K.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The search for thermoelectric (TE) materials with superior performance in energy conversion, a.k.a. figure of merit (ZT), that can compete against or be considered as alternates to traditional and commercially available materials such as CdTe and CuInSe2,1,2,3 is still ongoing. During the related materials design and discovery process, a prime importance is placed on the lattice thermal conductance (LTC) that determines the transport of thermal energy through the solid because materials with high LTC yield poor thermoelectric performance i.e., ZT, compared to those with lower LTC. Consequently, efficient TE materials with high \(ZT=\frac{S^2{\sigma} T}{\kappa_e \,+\, \kappa_L}\) performance require an optimization of both electrical and thermal properties. Here, S is the Seebeck coefficient, σ is the electrical conductivity, T is the temperature, κe and κL are electronic and phonon/lattice thermal conductivities, respectively. Materials with good TE properties are characterized with ZT ≥ 1 and typically should possess high S and σ values, but low κe and κL. The optimization is further complicated as κe and σ are directly proportional through the Wiedemann–Franz law (κe = LσT) where L is the temperature dependent Lorentz number. In order to boost ZT, materials with high power factor PF = S2σ are sought, by manipulating the charge carriers through tuning of effective mass by modifying the band gap as well as structural properties.4,5,6,7,8 This approach has led to the discovery of several high performing TE materials.9,10,11 However, certain shortcomings can be noted in the stability of these materials, potential toxicity of certain elements in their composition, and wider applicability. Additionally, questions remain on whether we can further push the limits of ZT to higher values for environmentally friendly TE materials.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

Chalcogenide perovskites have surfaced as potential candidates in this space. These materials have an ABX3 crystal structure and possess good optical and electronic properties, conducive for promising TE performance.5,18 Recent efforts have shown that an emerging chalcogenide perovskite, CaZrSe3, possesses notable optical and electrical properties relevant for energy conversion applications.19 Morelli and Slack20 recently defined low κL materials as those with κL ≤ 50 W m−1 K−1, while the rest are considered to possess high κL. It was identified that for non-metallic crystals, fundamental properties that contributed to lower κL included weak interatomic bonded interactions, presence of heavy elements, structural complexity, and large Grüneisen parameters.21 Here, we examine the phonon thermal transport mechanisms through CaZrSe3 in its orthorhombic distorted perovskite phase. We employ first principles calculations and linearized Boltzmann transport equation to probe fundamental lattice transport properties such as phonon dispersion, phonon lifetimes, average Grüneisen parameter and phonon group velocities to understand their effect on LTC, and predict κL and subsequently ZT for CaZrSe3. As discussed below in details, strong lattice anharmonicity, a high Debye temperature and short phonon lifetimes contribute to ultralow κL and competitive ZT predictions for potential TE applications.

Results and discussion

Phonon dispersion, density of states (DOS), and Debye temperature

The predicted structure, lattice properties, formation energy, and electronic band dispersion for CaZrSe3 are found elsewhere and not replicated here.19,22 The calculated phonon dispersion and DOS illustrated in Fig. 1a, b, respectively reveal that there are 60 phonon modes (3N, where N is 20 atoms per unit cell), while only three of those are acoustic modes (highlighted in Fig. 1a). The highest calculated phonon frequency is ~8.1 THz. The absence of negative frequency modes (in Fig. 1b) corroborates that there are no dynamical instabilities in the CaZrSe3 lattice structure. We find the highest frequency for the acoustic modes as 1.5 THz. There are no phonon band gaps between and within the acoustic and optical branches. Since there is strong coupling of the acoustic and optical modes, the latter are expected to marginally contribute to κL. The three acoustic modes, i.e., longitudinal acoustic (LA), transverse acoustic (TA) and flexural mode (ZA) are highlighted (red) in the phonon dispersion in Fig. 1a. The LA mode exhibits the highest acoustic frequency of 1.5 THz along the Γ–Z direction. As the acoustic modes represent the combined translational motion of the unit cell, the frequency is directly related to the total atomic mass in the cell and Se atoms being the largest contributor to the acoustic modes, a larger contribution to the DOS at any frequency is expected because the weight is ~ (mass)Se/(mass)unit-cell.

The phonon DOS shows that the greatest contribution to the acoustic modes is from the heavy Se atoms. The highest number of states for the phonons are noted at frequencies of ~2.5 and 5.3 THz, predominantly due to heavy Se atoms. Consequently, the contribution of the optical modes to CaZrSe3 LTC is primarily from Se atoms.

The variation of the average Grüneisen parameter (γ) with temperature, and the frequency dependence of the average phonon group velocities are displayed in Fig. 2a, b, respectively. The anharmonicity in the CaZrSe3 crystal lattice (indicative of bonding strength in the crystal lattice) is characterized by the γ that is a function of volume and calculated as the change in the vibrational frequency of a given mode with respect to volume, i.e., . According to the model proposed by Slack for phonon transport in crystals, κLis inversely proportional to γ.21 Higher γ will yield low LTC for TE materials. We predict γ = 3.75 at 300 K, implying significant anharmonicity in the orthorhombic perovskite structure, and hence CaZrSe3 should possess low κL. The higher γ = 3.75 value is an indication of the strong Zr-Se bonds in the perovskite framework. A discussion on the electronic and structural properties of CaZrSe3 is presented in a previous report.22 The strong covalent nature of the Zr–Se bond in the perovskite framework that yields such high γ value is observed in the strong overlap of Zr-d and Se-p orbitals in the DOS plot of Fig. 1. The highest phonon group velocities (Fig. 2b) in the acoustic region are ~5400 m/s, which is almost double the highest phonon group velocities for the optical modes. By calculating the number of phonon modes at each frequency (a.k.a. phonon number density), each data point in Fig. 2b represents a phonon mode at a specific q-point. The anisotropic dependence of the phonon group velocities along the different crystal directions are discussed in the Supplementary document (Fig. S1). Since the acoustic modes are the main contributors to the LTC of a crystal, the phonon number density in this region (<1.5 THz) is important in estimating κL. As the phonon number density in the acoustic region is very low relative to the optical part, we qualitatively assert that CaZrSe3 has a low κL. In general, the acoustic phonon group velocities are higher than the optical phonon group velocities. The optical phonon dispersion in Fig. 1a shows relatively flat lines compared to the acoustic modes along the Γ–Z, Γ–X, and Γ–Y directions.

Mean phonon transport properties in CaZrSe3. The (a) average Grüneisen parameter suggests considerable anharmonicity in the crystal structure, while the (b) average phonon group velocity shows low phonon number density for the acoustic modes. Both factors contribute to a significantly reduced κL. The intersection of the vertical and horizontal lines in (a) identifies the average Grüneisen parameter at 300 K.

This observation is indicative of the low group velocities for the optical modes compared to the acoustic modes and the subsequent low contribution of the optical phonon modes to the LTC of CaZrSe3. The phonon group velocities show a slight variation in the acoustic region due to the anisotropic effect observed in the phonon dispersion at frequencies of <1.5 THz while it remains virtually the same in the optical region owing to the dispersive nature of the phonon modes in such region as can be seen in Fig. 1a.

The LTC is sensitive to the magnitude and frequency dependence of the relaxation time (τ) which is shown in Fig. 3 for T = 300 K. The phonon lifetime is obtained from anharmonic three phonon–phonon scattering mechanisms or Umklapp processes. The phonon modes can be classified into two groups, one within ~1–3 THz and the other between ~3–8 THz. The longest lifetime (~4 ps) calculated for the phonons is for the modes in the acoustic region. τ decreases with increasing frequency due to enhanced phonon scattering events. The rate of decrease of τ is reduced above 4 THz. This behavior occurs because at 4 THz, the phonon number density begins to increase (yellow background) which leads to high scattering rates. Increased scattering rate subsequently leads to phonon annihilation and eventual decrease in the lifetime rate of decay. The calculated average τ = 1.2 ps. Although the significant phonon modes with long lifetimes lie within 0–2 THz, there are sparse modes with further extended lifetimes occurring in the acoustic region (<1.5 THz). The relatively short mean τ indicates enhanced phonon–phonon scattering rates that leads to annihilation of many phonon modes, and subsequent lowering of the κL.

The τ predictions agree with the phonon DOS (Fig. 1b) where the highest peaks are centered around 5.5 THz with contributions predominantly from the heavy Se atoms. The corresponding regions in Fig. 3 (displayed with yellow background) possess the highest phonon number density that contributes to strong Umklapp and phonon–phonon scattering interactions to consequentially yield a low LTC. Hence, we expect CaZrSe3 to have low lattice thermal conductivity. Although the optical branches contribute to the LTC, the effect of the coupling of the acoustic and optical modes (presented in Fig. 1) results in the lowest phonon lifetimes occurring in the optical region (3–8 THz). The high phonon number density in that region subsequently impedes the LTC.

We estimate the Debye temperature from the heat capacity of CaZrSe3 at the Dulong–Petit limit from Fig. 4. We find ΘD ~ 450 K implying that many phonon modes are inactive at lower temperatures which significantly inhibits the LTC in the crystal.

Lattice thermal conductivity and thermoelectric performance

Figure 5 presents the variation of CaZrSe3 kL as a function of temperature. We use the single-mode relaxation time approximation (RTA) method to estimate kL as it has been previously reported to predict suitably for low RTA materials compared to the full iterative solution.23 There is minimal or no anisotropic effect in the thermal conductivity. The minor anisotropic effect is noted within a narrow region between 50 and 400 K, while the highest kL is predicted along the lattice a direction. There is a sharp decrease in kL with temperature from 10–100 K but the rate of decrease is lowered between 100 and 400 K. The kL eventually saturates at 400 K. The inset in Fig. 5 shows a magnified version to highlight the calculated kL at 300 K. The inset also reveals that the kL is highest along a lattice direction, followed by the b direction while the lowest values are obtained along the c direction. At 300 K, kL = 1.27 W/m K along a direction, 1.16 W/m K along the b direction and 1.08 W/m K along the c direction. On average, kL = 1.17 W/m K. The lower kL for CaZrSe3 is commensurate with the strong anharmonicity in the crystal (high Grüneisen parameter) and the lower phonon number density in the acoustic region. Additionally, the shorter phonon lifetime that result in strong phonon–phonon interactions and scattering causes considerable reduction of kL.

We analyze the contributions of different phonon modes and the distance traveled by them to kL through the accumulated lattice thermal conductivity (κa). The predicted κa is normalized against κL and its dependence on frequency and phonon mean free path (MFP) is presented in Fig. 6a, b, respectively. At 300 K the calculated acoustic phonon modes (<1.5 THz) contribute ~50% to the calculated kL, while the lower optical phonon modes (1.5–6 THz) contribute ~45%. The higher optical modes contribute only 5% to κa. Approximately 95% of the calculated LTC is from the delocalized low frequency modes while the higher optical modes contribute insignificantly to the LTC. As temperature increases, ka/kL decreases due to increased phonon–phonon interactions and higher scattering rates. From 300 to 500 K, the κa is reduced by approximately one-half, with similar variations observed from 500 to 700 K, and from 700 to 900 K.

The variation of κa against the phonon MFP in Fig. 6b is indicative of the effect of the CaZrSe3 sample size. The size effect on the LTC is evaluated through summation of the contributions of all the phonon modes with MFP lower than the sample size. The phonon MFP is an effective tool for optimizing thermoelectric performance by reducing the thermal conductivity and potentially maintaining the electronic properties invariant. The LTC can be reduced by shrinking the system size, and shortening the phonon MFP. As such, Fig. 6b can facilitate optimizing the grain size of the CaZrSe3 crystal and enhance the thermoelectric figure of merit (ZT). The thermodynamic limit for the thermal carriers at 300 K is achieved at an MFP and an eventual crystal grain size of 138.1 nm. In the spirit of reducing LTC and improving ZT, nanostructuring CaZrSe3 with 10 nm size crystals reduces the conductivity by ~80% to 0.23 W/m.K and subsequently ZT is enhanced. Similar improvements are achievable at 500 K, 700 K and 900 K operating temperatures.

While a recent study22 computed the ZTe (upper limit to the thermoelectric figure of merit) of CaZrSe3, this work calculates ZT with quantitative predictions of kL at different temperatures. Figure 7 reports the ZT at different carrier concentrations and temperatures for both p-type and n-type doping. Between carrier concentrations of 1015–1017 cm−3, the calculated ZT values for both p- and n-type doping remain fairly constant until 650 K and drastically decrease beyond that at 1015 cm−3 carrier concentration. We corroborate that at lower carrier concentrations of 1015 cm−3, as the temperature increases, the electronic thermal conductivity (ke) provides a higher contribution to ZT than the electrical conductivity and as temperature increases beyond 600 K, ke increases considerably leading to lower ZT values. Further discussions on the kL and electrical conductivity of CaZrSe3 are available in our earlier work.22 At 1018 to 1020 cm−3, ZT increases with temperature for both p-type and n-type doping. At a higher carrier concentration of 1021 cm−3, the lowest ZT values are achieved and remain similar for p-type doping but with a hump between 300 and 600 K for n-type doping. For p-type doping the highest ZT (=1.004) is achieved at 1015 cm−3 at 550 and 600 K, while for 1016 cm−3, ZT = 1.000 at 600 K. For n-type doping, the highest ZT predictions occur for concentrations of 1015–1017 cm−3 while higher carrier concentrations result in low ZT. Trends in the calculated ZT values as observed for the p-type doping are also noted for the n-type doping. The highest ZT achieved for the n-type doping is 0.984 at 550 K at a carrier concentration of 1015 cm−3. The slightly higher ZT values for p-type doping than n-type doping is rooted in the higher carrier mobility for holes compared to electrons given that the latter possess relatively higher average effective masses.24 Also, concentrations in the range of 1017 cm−3 have been achieved in a related compound BaZrS3. Discussions on electronic properties and dispersion as well as the electronic contribution to ZT for CaZrSe3 have been presented earlier.22 The optimum ZT values can be observed at carrier concentrations of 1015–1017 cm−3 which is consistent with the experimental measurement of 10−17 cm−3 for BaZrS3. The high achievable ZT value indicates the high efficiency of CaZrSe3 films in converting thermal energy to electricity, since the difference between the calculated phonon MFP and the lattice parameter of CaZrSe3 is insignificant.

In summary, we employ detailed first principles calculations to understand the fundamental lattice transport mechanisms in CaZrSe3 and subsequently predict the lattice thermal conductivity (kL) and the thermoelectric figure of merit ZT. The linearized Boltzmann transport equations are solved and the phonon group velocities, phonon lifetimes and average Grüneisen parameter. The calculated average Grüneisen parameter of 3.75 shows strong anharmonicity in CaZrSe3 that contributes to low kL. A high Debye temperature of ~450 K indicates that only few phonon modes are active at lower temperatures leading to lower lattice thermal conductivity. To further examine the transport properties, we find that the phonon number density is relatively low, albeit with high group velocities, in the acoustic region of the phonon spectra. Though the acoustic modes yield the highest finite phonon group velocities, the low number density of such modes lead to low lattice thermal conductivity of CaZrSe3 as the modes have relatively longer MFP as well as low scattering rates. Additionally, short phonon lifetimes are calculated with the maximum to be ~3.5 ps. The above parameters result in kL = 1.17 W m−1 K−1 at 300 K. Phonons within the frequency range of 0–3 THz contribute ~80% to the LTC at 300 K, while acoustic phonons (<1.5 THz) contribute ~50% to the same. We note an insignificant anisotropy in kL between 50 and 300 K, with kL being highest along the lattice a direction. Considerable anharmonicity in the crystal indicated by the high Grüneisen parameter, a high Debye temperature, a reduced phonon number density in the acoustic region, all contribute towards the ultralow thermal conductivity of CaZrSe3.

The calculated thermodynamic limit at which phonons travel before annihilation is 138.1 nm. By nanostructuring CaZrSe3 at a scale of ~10 nm, kL can be further reduced by ~80% to attain 0.23 W m−1 K−1, to potentially enhance ZT. We compute ZT for different carrier concentrations across different temperatures and find that the highest ZT values are achieved for p-type doping compared to n-type doping. Also, lower carrier concentrations yield relatively higher ZT values. For p-type doping, a ZT value of 1.004 is calculated at carrier concentration of 1015 cm−3 and temperatures of 550 and 600 K. However, for n-type doping the highest ZT value of 0.984 is achieved at 550 K at a carrier concentration of 1015 cm−3. Since higher ZT is predicted for p-type doping compared to n-type doping, in designer CaZrSe3 thermoelectrics, optimum performance will be achieved at lower carrier concentrations and for p-type doping rather than n-type.

Methods

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

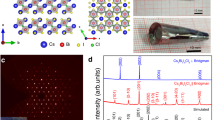

We use the projector augmented wave (PAW)25 method in the framework of DFT as implemented in the VASP26 code for all our first principles calculations. We utilize the PBEsol27 functional for solids to relax the unit cell and atomic positions, as well as the Methfessel–Paxton28 smearing scheme by setting the gamma parameter to 0.1 eV. An energy cutoff of 600 eV is employed for the planewaves expansion. In integrating the Brillouin zone, we use a Monkhorst–Pack29 special grid sampling that yields a 7 × 5 × 7 k-points representing 123 irreducible number of sampling points for all the bulk calculations. In resolving the Kohn–Sham equations, we consider the self-consistent field procedure by setting energy changes for each cycle at 10−4 eV as the convergence criterion between two successive iterations. The atomic forces are calculated by minimizing the total forces until the energy convergence is less than 10−8 eV. Figure 8 illustrates the crystal structure and lattice directions for CaZrSe3 in the orthorhombic distorted perovskite phase.

Phonon property predictions

The PHONOPY30 code is utilized to calculate the phonon dispersion, phonon group velocities, phonon DOS and Grüneisen parameters via a q-point sampling mesh of 21 × 21 × 21. The linearized Boltzmann transport equations are solved under the single-mode RTA for calculating κL through use of the PHONO3PY31 code. Converged results are obtained by using a q-point sampling mesh of 13 × 13 × 13. The second- and third-order force constants are computed by the supercell approach and the finite displacement method with a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell (160 atoms) and a 2 × 1 × 2 supercell (80 atoms) of the unit cell, respectively. The γ parameter is derived from the thermal data by averaging over all phonon modes including the optical branches at all q-points.

Calculation of the third-order force constants is computationally very demanding. We use an interaction cutoff to reduce the number of force constant calculations as tens of thousands of third-order force constants are needed when all three-atom interactions are considered. An interaction distance of up to the fourth nearest neighbors for the three-atom interactions is utilized to reduce the number of force constant calculations to 1257. We apply a non-analytical term correction to the dynamical matrix required to handle the long range dipole-dipole interactions.32,33,34 The Born effective charge tensors and the static dielectric constant tensors24,35,36,37,38 are symmetrized by their space-group and point group operations. Finally, we obtain \(\kappa_L=\frac{1}{NV_o}\sum_\zeta C_\lambda v_\lambda \otimes v_\lambda \tau_\lambda\). Here, N is the number of unit cells in the crystal, Vo is the volume of the unit cell, vλ is the group velocity and τλ is the relaxation time of the phonon mode λ, and Cλ is the mode dependent heat capacity.

Data availability

Data reported in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Post-processing codes used in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Restrictions apply to the availability of the simulation codes, which were used under license for this study.

References

Park, N.-G. Organometal perovskite light absorbers toward a 20% efficiency low-cost solid-state mesoscopic solar cell. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2423–2429 (2013).

Chen, Q. et al. Under the spotlight: the organic–inorganic hybrid halide perovskite for optoelectronic applications. Nano Today 10, 355–396 (2015).

Bisquert, J. The swift surge of perovskite photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2597–2598 (2013).

Zhou, H. et al. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014).

Burschka, J. et al. Sequential deposition as a route to high-performance perovskite-sensitized solar cells. Nature 499, 316–319 (2013).

Singh, R. & Balasubramanian, G. Impeding phonon transport through superlattices of organic–inorganic halide perovskites. RSC Adv. 7, 37015–37020 (2017).

Leijtens, T. et al. Overcoming ultraviolet light instability of sensitized TiO2 with meso-superstructured organometal tri-halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 4, 2885 (2013).

Noh, J. H., Im, S. H., Heo, J. H., Mandal, T. N. & Seok, S. I. Chemical management for colorful, efficient, and stable inorganic–organic hybrid nanostructured solar cells. Nano Lett. 13, 1764–1769 (2013).

Tan, G., Zhao, L.-D. & Kanatzidis, M. G. Rationally designing high-performance bulk thermoelectric materials. Chem. Rev. 116, 12123–12149 (2016).

Ge, Z.-H. et al. Low-cost, abundant binary sulfides as promising thermoelectric materials. Mater. Today 19, 227–239 (2016).

Zhao, L.-D., Dravid, V. P. & Kanatzidis, M. G. The panoscopic approach to high performance thermoelectrics. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 251–268 (2013).

Bennett, J. W., Grinberg, I. & Rappe, A. M. Effect of substituting of S for O: The sulfide perovskite BaZrS3 investigated with density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235115 (2009).

Pei, Y. et al. Convergence of electronic bands for high performance bulk thermoelectrics. Nature 473, 66–69 (2011).

Li, W. et al. Advances in environment-friendly SnTe thermoelectrics. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 2349–2355 (2017).

Banik, A., Shenoy, U. S., Saha, S., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. High power factor and enhanced thermoelectric performance of SnTe-AgInTe2: synergistic effect of resonance level and valence band convergence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13068–13075 (2016).

Repins, I. et al. 19.9%-efficient ZnO/CdS/CuInGaSe2 solar cell with 81.2% fill factor. Prog. Photovoltaics: Res. Appl. 16, 235–239 (2008).

Christians, J. A., Miranda Herrera, P. A. & Kamat, P. V. Transformation of the excited state and photovoltaic efficiency of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite upon controlled exposure to humidified air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1530–1538 (2015).

Snaith, H. J. Perovskites: the emergence of a new era for low-cost, high-efficiency solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 3623–3630 (2013).

Sun, Y.-Y., Agiorgousis, M. L., Zhang, P. & Zhang, S. Chalcogenide perovskites for photovoltaics. Nano Lett. 15, 581–585 (2015).

Morelli, D. T. & Slack, G. A. in High Thermal Conductivity Materials (eds Shindé, S. L. & Goela, J. S.) 37–68 (Springer, New York, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-25100-6_2.

Slack, G. A. Nonmetallic crystals with high thermal conductivity. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 34, 321–335 (1973).

Osei‐Agyemang, E., Adu, C. E. & Balasubramanian, G. Doping and anisotropy-dependent electronic transport in chalcogenide perovskite CaZrSe3 for high thermoelectric efficiency. Adv. Theory Simul., 1900060.

Shafique, A., Samad, A. & Shin, Y.-H. Ultra low lattice thermal conductivity and high carrier mobility of monolayer SnS2 and SnSe2: a first principles study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 20677–20683 (2017).

Gajdoš, M., Hummer, K., Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J. & Bechstedt, F. Linear optical properties in the projector-augmented wave methodology. Phys. Rev. B 73, 045112 (2006).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Hafner, J. Ab-initio simulations of materials using VASP: density-functional theory and beyond. J. Computational Chem. 29, 2044–2078 (2008).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A. T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Togo, A. & Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scr. Materialia 108, 1–5 (2015).

Togo, A., Chaput, L. & Tanaka, I. Distributions of phonon lifetimes in Brillouin zones. Phys. Rev. B 91, 094306 (2015).

Pick, R. M., Cohen, M. H. & Martin, R. M. Microscopic theory of force constants in the adiabatic approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1, 910–920 (1970).

Gonze, X., Charlier, J.-C., Allan, D. C. & Teter, M. P. Interatomic force constants from first principles: the case of α-quartz. Phys. Rev. B 50, 13035–13038 (1994).

Gonze, X. & Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, Born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 55, 10355–10368 (1997).

Wu, X., Vanderbilt, D. & Hamann, D. R. Systematic treatment of displacements, strains, and electric fields in density-functional perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. B 72, 035105 (2005).

Lee, C.-S., Kleinke, K. M. & Kleinke, H. Synthesis, structure, and electronic and physical properties of the two SrZrS3 modifications. Solid State Sci. 7, 1049–1054 (2005).

Gross, N. et al. Stability and band-gap tuning of the chalcogenide perovskite BaZrS3 in Raman and optical investigations at high pressures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 044014 (2017).

Grinberg, I. et al. Perovskite oxides for visible-light-absorbing ferroelectric and photovoltaic materials. Nature 503, 509–512 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through award CMMI-1753770. The computations were carried out on the cluster Sol managed by the Library and Technology Services Research Computing at Lehigh University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.O.-A. designed the project and analyzed the results. E.O.-A. and C.E.A. performed all the calculations. G.B. conceived the idea. E.O.-A. and G.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osei-Agyemang, E., Adu, C.E. & Balasubramanian, G. Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity of chalcogenide perovskite CaZrSe3 contributes to high thermoelectric figure of merit. npj Comput Mater 5, 116 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0253-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-019-0253-5

This article is cited by

-

Fast and accurate machine learning prediction of phonon scattering rates and lattice thermal conductivity

npj Computational Materials (2023)